Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▲ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

04 Jun 2019

Thermal regimes, but not mean temperatures, drive patterns of rapid climate adaptation at a continent-scale: evidence from the introduced European earwig across North AmericaJean-Claude Tourneur, Joël Meunier https://doi.org/10.1101/550319Temperature variance, rather than mean, drives adaptation to local climateRecommended by Fabien Aubret based on reviews by Ben Phillips and Eric GangloffClimate change is impacting eco-systems worldwide and driving many populations to move, adapt or go extinct. It is increasingly appreciated, for example, that species may adjust their phenology in response to climate change, although empirical data is scarce. In this preprint [1], Tourneur and Meunier report an impressive sampling effort in which life-history traits were measured across introduced populations of earwig in North America. The authors examine whether variation in life-history across populations is correlated with aspects of the thermal climate experienced by each population: mean temperature and seasonality of temperature. They find some fascinating correlations between life-history and thermal climate; correlations with the seasonality of temperature, but not with mean temperature. This study provides relatively uncommon data, in the sense that where most of the literature looking at adaptation in animals in response to climate change has focused on physiological traits [2, 3], this study examines changes in life-history traits with time scales relevant to impending climate change, and provides a reasonable argument that this is adaptation, not just constraint. References [1] Tourneur, J.-C. and Meunier, J. (2019). Thermal regimes, but not mean temperatures, drive patterns of rapid climate adaptation at a continent-scale: evidence from the introduced European earwig across North America. BioRxiv, 550319, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/550319 | Thermal regimes, but not mean temperatures, drive patterns of rapid climate adaptation at a continent-scale: evidence from the introduced European earwig across North America | Jean-Claude Tourneur, Joël Meunier | <p>The recent development of human societies has led to major, rapid and often inexorable changes in the environment of most animal species. Over the last decades, a growing number of studies formulated predictions on the modalities of animal adap... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Fabien Aubret | 2019-02-15 09:12:11 | View | |

01 Mar 2021

Social Conflicts in Dictyostelium discoideum : A Matter of ScalesForget, Mathieu; Adiba, Sandrine; De Monte, Silvia https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03088868/The cell-level perspective in social conflicts in Dictyostelium discoideumRecommended by Jeremy Van Cleve based on reviews by Peter Conlin and ?The social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum is an important model system for the study of cooperation and multicellularity as is has both unicellular and aggregative life phases. In the aggregative phase, which typically occurs when nutrients are limiting, individual cells eventually gather together to form a fruiting bodies whose spores may be dispersed to another, better, location and whose stalk cells, which support the spores, die. This extreme form of cooperation has been the focus of numerous studies that have revealed the importance genetic relatedness and kin selection (Hamilton 1964; Lehmann and Rousset 2014) in explaining the maintenance of this cooperative collective behavior (Strassmann et al. 2000; Kuzdzal-Fick et al. 2011; Strassmann and Queller 2011). However, much remains unknown with respect to how the interactions between individual cells, their neighbors, and their environment produce cooperative behavior at the scale of whole groups or collectives. In this preprint, Forget et al. (2021) describe how the D. discoideum system is crucial in this respect because it allows these cellular-level interactions to be studied in a systematic and tractable manner. References Forget, M., Adiba, S. and De Monte, S.(2021) Social conflicts in *Dictyostelium discoideum *: a matter of scales. HAL, hal-03088868, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03088868/ Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour. II. Journal of theoretical biology, 7(1), 17-52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(64)90039-6 Kuzdzal-Fick, J. J., Fox, S. A., Strassmann, J. E., and Queller, D. C. (2011). High relatedness is necessary and sufficient to maintain multicellularity in Dictyostelium. Science, 334(6062), 1548-1551. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1213272 Lehmann, L., and Rousset, F. (2014). The genetical theory of social behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1642), 20130357. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0357 Strassmann, J. E., and Queller, D. C. (2011). Evolution of cooperation and control of cheating in a social microbe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(Supplement 2), 10855-10862. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1102451108 Strassmann, J. E., Zhu, Y., & Queller, D. C. (2000). Altruism and social cheating in the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature, 408(6815), 965-967. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/35050087 Thompson, C. R., & Kay, R. R. (2000). Cell-fate choice in Dictyostelium: intrinsic biases modulate sensitivity to DIF signaling. Developmental biology, 227(1), 56-64. doi: https://doi.org/10.1006/dbio.2000.9877 | Social Conflicts in Dictyostelium discoideum : A Matter of Scales | Forget, Mathieu; Adiba, Sandrine; De Monte, Silvia | <p>The 'social amoeba' Dictyostelium discoideum, where aggregation of genetically heterogeneous cells produces functional collective structures, epitomizes social conflicts associated with multicellular organization. 'Cheater' populations that hav... | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Experimental Evolution | Jeremy Van Cleve | 2020-08-28 10:37:21 | View | ||

06 May 2019

When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexualsFlorian Lavigne, Guillaume Martin, Yoann Anciaux, Julien Papaïx, Lionel Roques https://doi.org/10.1101/433235Fisher to the rescueRecommended by François Blanquart and Florence Débarre based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe ability of a population to adapt to a new niche is an important phenomenon in evolutionary biology. The colonisation of a new volcanic island by plant species; the colonisation of a host treated by antibiotics by a-resistant strain; the Ebola virus transmitting from bats to humans and spreading epidemically in Western Africa, are all examples of a population invading a new niche, adapting and eventually establishing in this new environment. Adaptation to a new niche can be studied using source-sink models. In the original environment —the “source”—, the population enjoys a positive growth-rate and is self-sustaining, while in the new environment —the “sink”— the population has a negative growth rate and is able to sustain only by the continuous influx of migrants from the source. Understanding the dynamics of adaptation to the sink environment is challenging from a theoretical standpoint, because it requires modelling the demography of the sink as well as the transient dynamics of adaptation. Moreover, local selection in the sink and immigration from the source create distributions of genotypes that complicate the use of many common mathematical approaches. In their paper, Lavigne et al. [1], develop a new deterministic model of adaptation to a harsh sink environment in an asexual species. The fitness of an individual is maximal when a number of phenotypes are tuned to an optimal value, and declines monotonously as phenotypes are further away from this optimum. This model —called Fisher’s Geometric Model— generates a GxE interaction for fitness because the phenotypic optimum in the sink environment is distinct from that in the source environment [2]. The authors circumvent mathematical difficulties by developing an original approach based on tracking the deterministic dynamics of the cumulant generating function of the fitness distribution in the sink. They derive a number of important results on the dynamics of adaptation to the sink:

In conclusion, this theoretical work presents a method based on Fisher’s Geometric Model and the use of cumulant generating functions to resolve some aspects of adaptation to a sink environment. It generates a number of theoretical predictions for the adaptive colonisation of a sink by an asexual species with some standing genetic variation. It will be a fascinating task to examine whether these predictions hold in experimental evolution systems: will we observe the four phases of the dynamics of mean fitness in the sink environment? Will the rate of adaptation indeed be independent of the immigration rate? Is there an optimal rate of mutation for adaptation to the sink? Such critical tests of the theory will greatly improve our understanding of adaptation to novel environments. References [1] Lavigne, F., Martin, G., Anciaux, Y., Papaïx, J., and Roques, L. (2019). When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexuals. bioRxiv, 433235, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/433235 | When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexuals | Florian Lavigne, Guillaume Martin, Yoann Anciaux, Julien Papaïx, Lionel Roques | <p>The successful establishment of a population into a new empty habitat outside of its initial niche is a phenomenon akin to evolutionary rescue in the presence of immigration. It underlies a wide range of processes, such as biological invasions ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology | François Blanquart | 2018-10-03 20:59:16 | View | |

11 Mar 2020

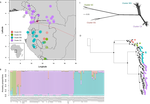

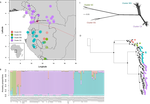

Phylogenomic approaches reveal how a climatic inversion and glacial refugia shape patterns of diversity in an African rain forest tree speciesAndrew J. Helmstetter, Biowa E. N. Amoussou, Kevin Bethune, Narcisse G. Kandem, Romain Glèlè Kakaï, Bonaventure Sonké, Thomas L. P. Couvreur https://doi.org/10.1101/807727Remarkable insights into processes shaping African tropical tree diversityRecommended by Michael Pirie based on reviews by Miguel de Navascués, Lars Chatrou and Oscar Vargas based on reviews by Miguel de Navascués, Lars Chatrou and Oscar Vargas

Tropical biodiversity is immense, under enormous threat, and yet still poorly understood. Global climatic breakdown and habitat destruction are impacting on and removing this diversity before we can understand how the biota responds to such changes, or even fully appreciate what we are losing [1]. This is particularly the case for woody shrubs and trees [2] and for the flora of tropical Africa [3]. Helmstetter et al. [4] have taken a significant step to improve our understanding of African tropical tree diversity in the context of past climatic change. They have done so by means of a remarkably in-depth analysis of one species of the tropical plant family Annonaceae: Annickia affinis [5]. A. affinis shows a distribution pattern in Africa found in various plant (but interestingly not animal) groups: a discontinuity between north and south of the equator [6]. There is no obvious physical barrier to cause this discontinuity, but it does correspond with present day distinct northern and southern rainy seasons. Various explanations have been proposed for this discontinuity, set out as hypotheses to be tested in this paper: climatic fluctuations resulting in changes in plant distributions in the Pleistocene, or differences in flowering times or in ecological niche between northerly and southerly populations. These explanations are not mutually exclusive, but they can be tested using phylogenetic inference – if you can sample variable enough sequence data from enough individuals – complemented with analysis of ecological niches and traits. Using targeted sequence capture, the authors amassed a dataset representing 351 nuclear markers for 112 individuals of A. affinis. This dataset is impressive for a number of reasons: First, sampling such a species across such a wide range in tropical Africa presents numerous challenges of itself. Second, the technical achievement of using this still relatively new sequencing technique with a custom set of baits designed specifically for this plant family [7] is also considerable. The result is a volume of data that just a few years ago would not have been feasible to collect, and which now offers the possibility to meaningfully analyse DNA sequence variation within a species across numerous independent loci of the nuclear genome. This is the future of our research field, and the authors have ably demonstrated some of its possibilities. Using this data, they performed on the one hand different population genetic clustering approaches, and on the other, different phylogenetic inference methods. I would draw attention to their use and comparison of coalescence and network-based approaches, which can account for the differences between gene trees that might be expected between populations of a single species. The results revealed four clades and a consistent sequence of divergences between them. The authors inferred past shifts in geographic range (using a continuous state phylogeographic model), depicting a biogeographic scenario involving a dispersal north over the north/south discontinuity; and demographic history, inferring in some (but not all) lineages increases in effective population size around the time of the last glacial maximum, suggestive of expansion from refugia. Using georeferenced specimen data, they compared ecological niches between populations, discovering that overlap was indeed smallest comparing north to south. Just the phenology results were effectively inconclusive: far better data on flowering times is needed than can currently be harvested from digitised herbarium specimens. Overall, the results add to the body of evidence for the impact of Pleistocene climatic changes on population structure, and for niche differences contributing to the present day north/south discontinuity. However, they also paint a complex picture of idiosyncratic lineage-specific responses, even within a single species. With the increasing accessibility of the techniques used here we can look forward to more such detailed analyses of independent clades necessary to test and to expand on these conclusions, better to understand the nature of our tropical plant diversity while there is still opportunity to preserve it for future generations. References [1] Mace, G. M., Gittleman, J. L., and Purvis, A. (2003). Preserving the Tree of Life. Science, 300(5626), 1707–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1085510 | Phylogenomic approaches reveal how a climatic inversion and glacial refugia shape patterns of diversity in an African rain forest tree species | Andrew J. Helmstetter, Biowa E. N. Amoussou, Kevin Bethune, Narcisse G. Kandem, Romain Glèlè Kakaï, Bonaventure Sonké, Thomas L. P. Couvreur | <p>The world’s second largest expanse of tropical rain forest is in Central Africa and it harbours enormous species diversity. Population genetic studies have consistently revealed significant structure across central African rain forest plants, i... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Michael Pirie | 2019-10-29 15:19:36 | View | |

31 Jan 2018

Identifying drivers of parallel evolution: A regression model approachSusan F Bailey, Qianyun Guo, Thomas Bataillon https://doi.org/10.1101/118695A new statistical tool to identify the determinant of parallel evolutionRecommended by Stephanie Bedhomme based on reviews by Bastien Boussau and 1 anonymous reviewerIn experimental evolution followed by whole genome resequencing, parallel evolution, defined as the increase in frequency of identical changes in independent populations adapting to the same environment, is often considered as the product of similar selection pressures and the parallel changes are interpreted as adaptive. References [1] Bailey SF, Guo Q and Bataillon T (2018) Identifying drivers of parallel evolution: A regression model approach. bioRxiv 118695, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/118695 [2] Lang GI, Rice DP, Hickman, MJ, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Botstein D, and Desai MM (2013) Pervasive genetic hitchhiking and clonal interference in forty evolving yeast populations. Nature 500: 571–574. doi: 10.1038/nature12344 | Identifying drivers of parallel evolution: A regression model approach | Susan F Bailey, Qianyun Guo, Thomas Bataillon | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (http://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100045). Parallel evolution, defined as identical changes arising in independent populations, is often attributed... |  | Experimental Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Stephanie Bedhomme | 2017-03-22 14:54:48 | View | |

28 Feb 2018

Insects and incest: sib-mating tolerance in natural populations of a parasitoid waspMarie Collet, Isabelle Amat, Sandrine Sauzet, Alexandra Auguste, Xavier Fauvergue, Laurence Mouton, Emmanuel Desouhant https://doi.org/10.1101/169268Incestuous insects in nature despite occasional fitness costsRecommended by Caroline Nieberding and Bertanne Visser based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersInbreeding, or mating between relatives, generally lowers fitness [1]. Mating between genetically similar individuals can result in higher levels of homozygosity and consequently a higher frequency with which recessive disease alleles may be expressed within a population. Reduced fitness as a consequence of inbreeding, or inbreeding depression, can vary between individuals, sexes, populations and species [2], but remains a pervasive challenge for many organisms with small local population sizes, including humans [3]. But all is not lost for individuals within small populations, because an array of mechanisms can be employed to evade the negative effects of inbreeding [4], including sib-mating avoidance and dispersal [5, 6]. Despite thorough investigation of inbreeding and sib-mating avoidance in the laboratory, only very few studies have ventured into the field besides studies on vertebrates and eusocial insects. The study of Collet et al. [7] is a surprising exception, where the effect of male density and frequency of relatives on inbreeding avoidance was tested in the laboratory, after which robust field collections and microsatellite genotyping were used to infer relatedness and dispersal in natural populations. The parasitic wasp Venturia canescens is an excellent model system to study inbreeding, because mating success was previously found to decrease with increasing relatedness between mates in the laboratory [8] and this species thus suffers from inbreeding depression [9–11]. The authors used an elegant design combining population genetics and model simulations to estimate relatedness of mating partners in the field and compared that with a theoretical distribution of potential mate encounters when random mating is assumed. One of the most important findings of this study is that mating between siblings is not avoided in this species in the wild, despite negative fitness effects when inbreeding does occur. Similar findings were obtained for another insect species, the field cricket Gryllus campestris [12], which leaves us to wonder whether inbreeding tolerance could be more common in nature than currently appreciated. The authors further looked into sex-specific dispersal patterns between two patches located a few hundred meters apart. Females were indeed shown to be more related within a patch, but no genetic differences were observed between males, suggesting that V. canescens males more readily disperse. Moreover, microsatellite data at 18 different loci did not reveal genetic differentiation between populations approximately 300 kilometers apart. Gene flow is thus occurring over considerable distances, which could play an important role in the ability of this species to avoid negative fitness consequences of inbreeding in nature. Another interesting aspect of this work is that discrepancies were found between laboratory- and field-based data. What is the relevance of laboratory-based experiments if they cannot predict what is happening in the wild? Many, if not most, biologists (including us) bring our model system into the laboratory to control, at least to some extent, the plethora of environmental factors that could potentially affect our system (in ways that we do not want). Most behavioral studies on mating patterns and sexual selection are conducted in standardized laboratory conditions, but sexual selection is in essence social selection, because an individual’s fitness is partly determined by the phenotype of its social partners (i.e. the social environment) [13]. The social environment may actually dictate the expression of female mate choice and it is unclear how potential laboratory-induced social biases affect mating outcome. In V. canescens, findings using field-caught individuals paint a completely opposite picture of what was previously shown in the laboratory, i.e. sib-avoidance is not taking place in the field. It is likely that density, level of relatedness, sex ratio in the field, and/or the size of experimental arenas in the lab are all factors affecting mate selectivity, as we have previously shown in a butterfly [14–16]. If females, for example, typically only encounter a few males in sequence in the wild, it may be problematic for them to express choosiness when confronted simultaneously with two or more males in the laboratory. A recent study showed that, in the wild, female moths take advantage of staying in groups to blur male choosiness [17]. It is becoming more and more clear that what we observe in the laboratory may not actually reflect what is happening in nature [18]. Instead of ignoring the species-specific life history and ecological features of our favorite species when conducting lab experiments, we suggest that it is time to accept that we now have the theoretical foundations to tease apart what in this “environmental noise” actually shapes sexual selection in nature. Explicitly including ecology in studies on sexual selection will allow us to make more meaningful conclusions, i.e. rather than “this is what may happen in the wild”, we would be able to state “this is what often happens in nature”. References [1] Charlesworth D & Willis JH. 2009. The genetics of inbreeding depression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10: 783–796. doi: 10.1038/nrg2664 | Insects and incest: sib-mating tolerance in natural populations of a parasitoid wasp | Marie Collet, Isabelle Amat, Sandrine Sauzet, Alexandra Auguste, Xavier Fauvergue, Laurence Mouton, Emmanuel Desouhant | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (http://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100047) 1. Sib-mating avoidance is a pervasive behaviour that likely evolves in species subject to inbreeding dep... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Sexual Selection | Caroline Nieberding | 2017-07-28 09:23:20 | View | |

09 Feb 2018

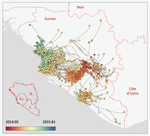

Phylodynamic assessment of intervention strategies for the West African Ebola virus outbreakSimon Dellicour, Guy Baele, Gytis Dudas, Nuno R. Faria, Oliver G. Pybus, Marc A. Suchard, Andrew Rambaut, Philippe Lemey https://doi.org/10.1101/163691Simulating the effect of public health interventions using dated virus sequences and geographical dataRecommended by Samuel Alizon based on reviews by Christian Althaus, Chris Wymant and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Christian Althaus, Chris Wymant and 1 anonymous reviewer

Perhaps because of its deadliness, the 2013-2016 Ebola Virus (EBOV) epidemics in West-Africa has led to unprecedented publication and sharing of full virus genome sequences. This was both rapid (90 full genomes were shared within weeks [1]) and important (more than 1500 full genomes have been released overall [2]). Furthermore, the availability of the metadata (especially GPS location) has led to depth analyses of the geographical spread of the epidemics [3]. References [1] Gire et al. 2014. Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the 2014 outbreak. Science 345: 1369–1372. doi: 10.1126/science.1259657. | Phylodynamic assessment of intervention strategies for the West African Ebola virus outbreak | Simon Dellicour, Guy Baele, Gytis Dudas, Nuno R. Faria, Oliver G. Pybus, Marc A. Suchard, Andrew Rambaut, Philippe Lemey | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100046). The recent Ebola virus (EBOV) outbreak in West Africa witnessed considerable efforts to obtain viral genom... |  | Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Samuel Alizon | 2017-09-30 13:49:57 | View | |

08 Aug 2018

Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutationsE. Noël, E. Fruitet, D. Lelaurin, N. Bonel, A. Ségard, V. Sarda, P. Jarne and P. David https://doi.org//273367Inbreeding compensates for reduced sexual selection in purging deleterious mutationsRecommended by Charles Baer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTwo evolutionary processes have been shown in theory to enhance the effects of natural selection in purging deleterious mutations from a population (here ""natural"" selection is defined as ""selection other than sexual selection""). First, inbreeding, especially self-fertilization, facilitates the removal of deleterious recessive alleles, the effects of which are largely hidden from selection in heterozygotes when mating is random. Second, sexual selection can facilitate the removal of deleterious alleles of arbitrary dominance, with little or no demographic cost, provided that deleterious effects are greater in males than in females (""genic capture""). Inbreeding (especially selfing) and sexual selection are often negatively correlated in nature. Empirical tests of the role of sexual selection in purging deleterious mutations have been inconsistent, potentially due to the positive relationship between sexual selection and intersexual genetic conflict. References [1] Noël, E., Fruitet, E., Lelaurin, D., Bonel, N., Segard, A., Sarda, V., Jarne, P., & David P. (2018). Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutations. bioRxiv, 273367, ver. 3 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/273367 | Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutations | E. Noël, E. Fruitet, D. Lelaurin, N. Bonel, A. Ségard, V. Sarda, P. Jarne and P. David | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (https://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100055). Theory and empirical data showed that two processes can boost selection against deleterious mutations, ... |  | Adaptation, Experimental Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Charles Baer | Anonymous | 2018-03-01 08:12:37 | View |

13 Dec 2018

A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid waspsD. Di Giovanni, D. Lepetit, M. Boulesteix, M. Ravallec, J. Varaldi https://doi.org/10.1101/342758Genetic intimacy of filamentous viruses and endoparasitoid waspsRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Alejandro Manzano Marín and 1 anonymous reviewerViruses establish intimate relationships with the cells they infect. The virocell is a novel entity, different from the original host cell and beyond the mere combination of viral and cellular genetic material. In these close encounters, viral and cellular genomes often hybridise, combine, recombine, merge and excise. Such chemical promiscuity leaves genomics scars that can be passed on to descent, in the form of deletions or duplications and, importantly, insertions and back and forth exchange of genetic material between viruses and their hosts. References [1] Di Giovanni, D., Lepetit, D., Boulesteix, M., Ravallec, M., & Varaldi, J. (2018). A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid wasps. bioRxiv, 342758, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/342758 | A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid wasps | D. Di Giovanni, D. Lepetit, M. Boulesteix, M. Ravallec, J. Varaldi | <p>To circumvent host immune response, numerous hymenopteran endo-parasitoid species produce virus-like structures in their reproductive apparatus that are injected into the host together with the eggs. These viral-like structures are absolutely n... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution | Ignacio Bravo | 2018-07-18 15:59:14 | View | |

26 Oct 2020

Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing populationMiguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.080895Detecting loci under natural selection from temporal genomic data of selfing populationsRecommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

The observed levels of genomic diversity in contemporary populations are the result of changes imposed by several evolutionary processes. Among them, natural selection is known to dramatically shape the genetic diversity of loci associated with phenotypes which affect the fitness of carriers. As such, many efforts have been dedicated towards developing methods to detect signatures of natural selection from genomes of contemporary samples [1]. References [1] Stern AJ, Nielsen R (2019) Detecting Natural Selection. In: Handbook of Statistical Genomics , pp. 397–40. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119487845.ch14 | Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population | Miguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis | <p>Tracking genetic changes of populations through time allows a more direct study of the evolutionary processes acting on the population than a single contemporary sample. Several statistical methods have been developed to characterize the demogr... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Matteo Fumagalli | 2020-05-08 10:34:31 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer