Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▲ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

04 Aug 2023

Sensitive windows for within- and trans-generational plasticity of anti-predator defencesJuliette Tariel-Adam; Émilien Luquet; Sandrine Plénet https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/mr8huSensitive windows for phenotypic plasticity within and across generations; where empirical results do not meet the theory but open a world of possibilitiesRecommended by Benoit Pujol based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker, Timothée Bonnet and Willem FrankenhuisIt is easy to define phenotypic plasticity as a mechanism by which traits change in response to a modification of the environment. Many complex mechanisms are nevertheless involved with plastic responses, their strength, and stability (e.g., reliability of cues, type of exposure, genetic expression, epigenetics). It is rather intuitive to think that environmental cues perceived at different stages of development will logically drive different phenotypic responses (Fawcett and Frankenhuis 2015). However, it has proven challenging to try and explain, or model how and why different effects are caused by similar cues experienced at different developmental or life stages (Walasek et al. 2022). The impact of these ‘sensitive windows’ on the stability of plastic responses within or across generations remains unclear. In their paper entitled “Sensitive windows for within- and trans-generational plasticity of anti-predator defences”, Tariel-Adam (2023) address this question. In this paper, Tariel et al. acknowledge the current state of the art, i.e., that some traits influenced by the environment at early life stages become fixed later in life (Snell-Rood et al. 2015) and that sensitive windows are therefore more likely to be observed during early stages of development. Constructive exchanges with the reviewers illustrated that Tariel et al. presented a clear picture of the knowledge on sensitive windows from a conceptual and a mechanistic perspective, thereby providing their study with a strong and elegant rationale. Tariel et al. outlined that little is known about the significance of this scenario when it comes to transgenerational plasticity. Theory predicts that exposure late in the life of parents should be more likely to drive transgenerational plasticity because the cue perceived by parents is more likely to be reliable if time between parental exposure and offspring expression is short (McNamara et al. 2016). I would argue that although sensible, this scenario is likely oversimplifying the complexity of evolutionary, ecological, and inheritance mechanisms at play (Danchin et al. 2018). Tariel-Adam et al. (2023) point out in their paper how the absence of experimental results limits our understanding of the evolutionary and adaptive significance of transgenerational plasticity and decided to address this broad question. Tariel-Adam et al. (2023) used the context of predator-prey interactions, which is a powerful framework to evaluate the temporality of predator cues and prey responses within and across generations (Sentis et al. 2018). They conducted a very elegant experiment whereby two generations of freshwater snails Physa acuta were exposed to crayfish predator cues at different developmental windows. They triggered the within-generation phenotypic plastic response of inducible defences (e.g., shell thickness) and identified sensitive windows as to evaluate their role in within-generation phenotypic plasticity versus transgenerational plasticity. They used different linear models, which lead to constructive exchanges with reviewers, and between reviewers, well trained on these approaches, in particular on effect sizes, that improved the paper by pushing the discussion all the way towards a consensus. Tariel-Adam et al. (2023) results showed that the phenotypic plastic response of different traits was associated with different sensitive windows. Although early-life development was confirmed to be a sensitive window, it was far from being the only developmental stage driving within-generation plastic responses of defence traits. This finding contributes to change our views on plasticity because where theoretical models predict early- and late-life sensitive windows, empirical results gathered here present a more continuous opportunity for sensitive windows over the lifetime of freshwater snails. This is likely because multifactorial mechanisms drive the reliability and adaptive significance of predator cues. To me, this paper most original contribution lies probably in the empirical investigation of sensitive windows underlying transgenerational plasticity. Their finding implies mechanistic ties between sensitive windows driving within-generation and transgenerational plasticity for some traits, but they also shed light on the possible independence of these processes. Although one may be disheartened by these findings illustrating the ability of nature to combine complex mechanisms in order to produce somewhat unpredictable scenarios, one can only find that this unlimited range of phenotypic plasticity scenarios is a wonder to investigate because much remains to be understood. As mentioned in the conclusion of the paper, the opportunity for sensitive windows to drive such a range of plastic responses may also be an opportunity for organisms to adapt to a wide range of environmental demands. References Danchin E, A Pocheville, O Rey, B Pujol, and S Blanchet (2019). Epigenetically facilitated mutational assimilation: epigenetics as a hub within the inclusive evolutionary synthesis. Biological Reviews, 94: 259-282. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12453 Fawcett TW, and WE Frankenhuis (2015). Adaptive Explanations for Sensitive Windows in Development. Frontiers in Zoology 12, S3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-9994-12-S1-S3 McNamara JM, SRX Dall, P Hammerstein, and O Leimar (2016). Detection vs. Selection: Integration of Genetic, Epigenetic and Environmental Cues in Fluctuating Environments. Ecology Letters 19, 1267–1276. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12663 Sentis A, R Bertram, N Dardenne, et al. (2018). Evolution without standing genetic variation: change in transgenerational plastic response under persistent predation pressure. Heredity 121, 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-018-0108-8 Snell-Rood EC, EM Swanson, and RL Young (2015). Life History as a Constraint on Plasticity: Developmental Timing Is Correlated with Phenotypic Variation in Birds. Heredity 115, 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2015.47 Tariel-Adam J, E Luquet, and S Plénet (2023). Sensitive windows for within- and trans-generational plasticity of anti-predator defences. OSF preprints, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/mr8hu Walasek N, WE Frankenhuis, and K Panchanathan (2022). An Evolutionary Model of Sensitive Periods When the Reliability of Cues Varies across Ontogeny. Behavioral Ecology 33, 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arab113 | Sensitive windows for within- and trans-generational plasticity of anti-predator defences | Juliette Tariel-Adam; Émilien Luquet; Sandrine Plénet | <p>Transgenerational plasticity could be an important mechanism for adaptation to variable environments in addition to within-generational plasticity. But its potential for adaptation may be restricted to specific developmental windows that are hi... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Benoit Pujol | 2022-11-14 08:08:27 | View | |

11 Apr 2023

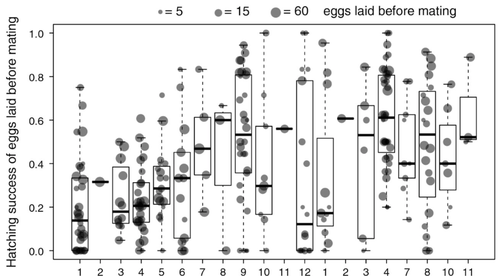

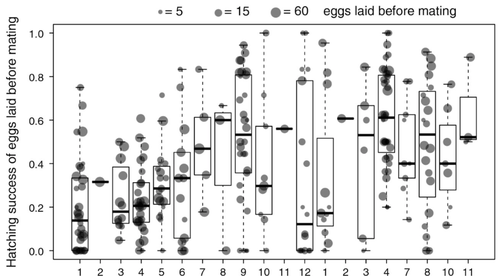

Facultative parthenogenesis: a transient state in transitions between sex and obligate asexuality in stick insects?Chloé Larose, Guillaume Lavanchy, Susana Freitas, Darren J. Parker, Tanja Schwander https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.25.485836Facultative parthenogenesis and transitions from sexual to asexual reproductionRecommended by Trine Bilde based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Despite a vast array of ways in which organisms can reproduce (Bell, 1982), most animals engage in sexual reproduction (Otto & Lenormand, 2002). A fascinating alternative to sex is parthenogenesis, where offspring are produced asexually from a gamete, typically the egg, without receiving genetic material from another gamete (Simon, Delmotte, Rispe, & Crease, 2003). One of the long-standing questions in the field is why parthenogenesis is not more widespread, given the costs associated with sex (Otto & Lenormand, 2002). Natural populations of most species appear to be reproducing either sexually or parthenogenetically, even if a species can employ both reproductive modes (Larose et al 2023). Larose et al (2023) highlight the conundrum in this pattern, as organisms that are capable of employing parthenogenesis facultatively would be able to gain the benefits of both modes of reproduction. Why then, is facultative parthenogenesis not more common? Larose et al (2023) propose that constraints on being efficient in both sexual and asexual reproduction could cause a trade-off between reproductive modes that favours an obligate strategy of either sex or no sex. This would provide an explanation for why facultative parthenogenesis is rare. Timema stick insects provide an excellent system to investigate reproductive strategies, as some species have parthenogenetic females, while other species are sexual, and they show repeated transitions from sexual reproduction to obligate parthenogenesis (Schwander & Crespi, 2009). The authors performed comprehensive and complementary studies in a recently discovered species T. douglasi, in which populations show both modes of reproduction, with some populations consisting only of females and others showing equal proportions of males and females. The sex ratio varied significantly, with the proportion of females ranging between 43-100% across 29 populations. These populations form a monophyletic clade with clustering into three genetic lineages and only a few cases of admixture. Females from all populations were capable of producing unfertilized eggs, but the hatching success varied hugely among populations and lineages (3-100%). Parthenogenetically produced offspring were homozygous, showing that parthenogenesis causes a complete loss of heterozygosity in a single generation. After producing eggs as virgins, females were mated to assess the capacity to also reproduce sexually, and fertilization increased the hatching success of eggs in two lineages. In one lineage, in which the hatching success of unfertilized eggs is similar to that of other sexually reproducing Timema species, fertilization reduced egg-hatching success, indicating a trade-off between reproductive modes with parthenogenetic reproduction performing best. Approximately 58% of the offspring produced after mating were fertilized, demonstrating the capacity of females to reproduce parthenogenetically also after mating has occurred, however with huge variation among individuals. This wonderful and meticulously performed study produces strong and complementary evidence for facultative parthenogenesis in T. douglasi populations. The study shows large variation in how reproductive mode is employed, supporting the existence of a trade-off between sexual and parthenogenetic reproduction. This might be an example of an ongoing transition from sexual to asexual reproduction, which indicates that obligate parthenogenesis may derive via transient facultative parthenogenesis. REFERENCES Bell, G. (1982) The Masterpiece of Nature: The Evolution and Genetics of Sexuality. University of California Press. 635 p. Otto, S. P., & Lenormand, T. (2002). Resolving the paradox of sex and recombination. Nature Reviews Genetics, 3(4), 252-261. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg761 Schwander, T., & Crespi, B. J. (2009). Multiple direct transitions from sexual reproduction to apomictic parthenogenesis in Timema stick insects. Evolution, 63(1), 84-103. Simon, J.-C., Delmotte, F., Rispe, C., & Crease, T. (2003). Phylogenetic relationships between parthenogens and their sexual relatives: the possible routes to parthenogenesis in animals. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 79(1), 151-163. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1095-8312.2003.00175.x Larose, C., Lavanchy, G., Freitas, S., Parker, D.J., Schwander, T. (2023) Facultative parthenogenesis: a transient state in transitions between sex and obligate asexuality in stick insects? bioRxiv, 2022.03.25.485836, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.25.485836 | Facultative parthenogenesis: a transient state in transitions between sex and obligate asexuality in stick insects? | Chloé Larose, Guillaume Lavanchy, Susana Freitas, Darren J. Parker, Tanja Schwander | <p>Transitions from obligate sex to obligate parthenogenesis have occurred repeatedly across the tree of life. Whether these transitions occur abruptly or via a transient phase of facultative parthenogenesis is rarely known. We discovered and char... |  | Reproduction and Sex | Trine Bilde | 2022-05-20 10:41:13 | View | |

12 Nov 2021

How ancient forest fragmentation and riparian connectivity generate high levels of genetic diversity in a micro-endemic Malagasy treeJordi Salmona, Axel Dresen, Anicet E. Ranaivoson, Sophie Manzi, Barbara Le Pors, Cynthia Hong-Wa, Jacqueline Razanatsoa, Nicole V. Andriaholinirina, Solofonirina Rasoloharijaona, Marie-Elodie Vavitsara, Guillaume Besnard https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.25.394544An ancient age of open-canopy landscapes in northern Madagascar? Evidence from the population genetic structure of a forest treeRecommended by Miguel de Navascués based on reviews by Katharina Budde and Yurena Arjona based on reviews by Katharina Budde and Yurena Arjona

We currently live in the Anthropocene, the geological age characterized by a profound impact of human populations in the ecosystems and the environment. While there is little doubt about the action of humans in the shaping of present landscapes, it can be difficult to determine what the state of those landscapes was before humans started to modify them. This is the case of the Madagascar grasslands, whose origins have been debated with arguments proposing them either as anthropogenic, created with the arrival of humans around 2000BP, or as ancient features of the natural landscape with a forest fragmentation process due to environmental changes pre-dating human arrival [e.g. 1,2]. One way to clarify this question is through the genetic study of native species. Population continuity and fragmentation along time shape the structure of the genetic diversity in space. Species living in a uniform continuous habitat are expected to show genetic structuring determined only by geographical distance. Recent changes of the habitat can take many generations to reshape that genetic structure [3]. Thus, we expect genetic structure to reflect ancient features of the landscape. The work by Jordi Salmona and collaborators [4] studies the factors determining the population genetic structure of the Malagasy spiny olive (Noronhia spinifolia). This narrow endemic species is distributed in the discontinuous forest patches of the Loky-Manambato region (northern Madagascar). Jordi Salmona and collaborators genotyped 72 individuals distributed across the species distribution with restriction associated DNA sequencing and organelle microsatellite markers. Then, they studied the population genetic structure of the species. Using isolation-by-resistance models [5], they tested the influence of several landscape features (forest cover, roads, rivers, slope, etc.) on the connectivity between populations. Maternally inherited loci (chloroplast and mitochondria) and bi-parentally inherited loci (nuclear), were analysed separately in an attempt to identify the role of pollen and seed dispersal in the connectivity of populations. Despite the small distribution of the species, Jordi Salmona and collaborators [4] found remarkable levels of genetic diversity. The spatial structure of this diversity was found to be mainly explained by the forest cover of the landscape, suggesting that the landscape has been composed by patches of forests and grasslands for a long time. The main role of forest cover for the connectivity among populations also highlights the importance of riparian forest as dispersal corridors. Finally, differences between organelle and nuclear markers were not enough to establish any strong conclusion about the differences between pollen and seed dispersal. The results presented by Jordi Salmona and collaborators [4] contribute to the understanding of the history and ecology of understudied Madagascar ecosystems. Previous population genetic studies in some forest-dwelling mammals have been interpreted as supporting an old age for the fragmented landscapes in northern Madagascar [e.g. 1,6]. To my knowledge, this is the first study on a tree species. While this work might not completely settle the debate, it emphasizes the importance of studying a diversity of species to understand the biogeographic dynamics of a region. References 1. Quéméré, E., X. Amelot, J. Pierson, B. Crouau-Roy, L. Chikhi (2012) Genetic data suggest a natural prehuman origin of open habitats in northern Madagascar and question the deforestation narrative in this region. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of | How ancient forest fragmentation and riparian connectivity generate high levels of genetic diversity in a micro-endemic Malagasy tree | Jordi Salmona, Axel Dresen, Anicet E. Ranaivoson, Sophie Manzi, Barbara Le Pors, Cynthia Hong-Wa, Jacqueline Razanatsoa, Nicole V. Andriaholinirina, Solofonirina Rasoloharijaona, Marie-Elodie Vavitsara, Guillaume Besnard | <p>Understanding landscape changes is central to predicting evolutionary trajectories and defining conservation practices. While human-driven deforestation is intense throughout Madagascar, exception in areas like the Loky-Manambato region (North)... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Miguel de Navascués | 2020-11-27 09:07:21 | View | |

30 Aug 2021

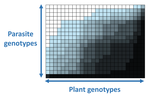

The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactionsMoury Benoît, Audergon Jean-Marc, Baudracco-Arnas Sylvie, Ben Krima Safa, Bertrand François, Boissot Nathalie, Buisson Mireille, Caffier Valérie, Cantet Mélissa, Chanéac Sylvia, Constant Carole, Delmotte François, Dogimont Catherine, Doumayrou Juliette, Fabre Frédéric, Fournet Sylvain, Grimault Valérie, Jaunet Thierry, Justafré Isabelle, Lefebvre Véronique, Losdat Denis, Marcel Thierry C., Montarry Josselin, Morris Cindy E., Omrani Mariem, Paineau Manon, Perrot Sophie, Pilet-Nayel Marie-Laure, R... https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433745Nestedness and modularity in plant-parasite infection networksRecommended by Santiago Elena based on reviews by Rubén González and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Rubén González and 2 anonymous reviewers

In a landmark paper, Flores et al. (2011) showed that the interactions between bacteria and their viruses could be nicely described using a bipartite infection networks. Two quantitative properties of these networks were of particular interest, namely modularity and nestedness. Modularity emerges when groups of host species (or genotypes) shared groups of viruses. Nestedness provided a view of the degree of specialization of both partners: high nestedness suggests that hosts differ in their susceptibility to infection, with some highly susceptible host genotypes selecting for very specialized viruses while strongly resistant host genotypes select for generalist viruses. Translated to the plant pathology parlance, this extreme case would be equivalent to a gene-for-gene infection model (Flor 1956): new mutations confer hosts with resistance to recently evolved viruses while maintaining resistance to past viruses. Likewise, virus mutations for expanding host range evolve without losing the ability to infect ancestral host genotypes. By contrast, a non-nested network would represent a matching-allele infection model (Frank 2000) in which each interacting organism evolves by losing its capacity to resist/infect its ancestral partners, resembling a Red Queen dynamic. Obviously, the reality is more complex and may lie anywhere between these two extreme situations. Recently, Valverde et al. (2020) developed a model to explain the emergence of nestedness and modularity in plant-virus infection networks across diverse habitats. They found that local modularity could coexist with global nestedness and that intraspecific competition was the main driver of the evolution of ecosystems in a continuum between nested-modular and nested networks. These predictions were tested with field data showing the association between plant host species and different viruses in different agroecosystems (Valverde et al. 2020). The effect of interspecific competition in the structure of empirical plant host-virus infection networks was also tested by McLeish et al. (2019). Besides data from agroecosystems, evolution experiments have also shown the pervasive emergence of nestedness during the diversification of independently-evolved lineages of potyviruses in Arabidopsis thaliana genotypes that differ in their susceptibility to infection (Hillung et al. 2014; González et al. 2019; Navarro et al. 2020). In their study, Moury et al. (2021) have expanded all these previous observations to a diverse set of pathosystems that range from viruses, bacteria, oomycetes, fungi, nematodes to insects. While modularity was barely seen in only a few of the systems, nestedness was a common trend (observed in ~94% of all systems). This nestedness, as seen in previous studies and as predicted by theory, emerged as a consequence of the existence of generalist and specialist strains of the parasites that differed in their capacity to infect more or less resistant plant genotypes. As pointed out by Moury et al. (2021) in their conclusions, the ubiquity of nestedness in plant-parasite infection matrices has strong implications for the evolution and management of infectious diseases. References Flor, H. H. (1956). The complementary genic systems in flax and flax rust. In Advances in genetics, 8, 29-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60498-8 Flores, C. O., Meyer, J. R., Valverde, S., Farr, L., and Weitz, J. S. (2011). Statistical structure of host–phage interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, E288-E297. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1101595108 Frank, S. A. (2000). Specific and non-specific defense against parasitic attack. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 202, 283-304. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.1999.1054 González, R., Butković, A., and Elena, S. F. (2019). Role of host genetic diversity for susceptibility-to-infection in the evolution of virulence of a plant virus. Virus evolution, 5(2), vez024. https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/vez052 Hillung, J., Cuevas, J. M., Valverde, S., and Elena, S. F. (2014). Experimental evolution of an emerging plant virus in host genotypes that differ in their susceptibility to infection. Evolution, 68, 2467-2480. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12458 McLeish, M., Sacristán, S., Fraile, A., and García-Arenal, F. (2019). Coinfection organizes epidemiological networks of viruses and hosts and reveals hubs of transmission. Phytopathology, 109, 1003-1010. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-08-18-0293-R Moury B, Audergon J-M, Baudracco-Arnas S, Krima SB, Bertrand F, Boissot N, Buisson M, Caffier V, Cantet M, Chanéac S, Constant C, Delmotte F, Dogimont C, Doumayrou J, Fabre F, Fournet S, Grimault V, Jaunet T, Justafré I, Lefebvre V, Losdat D, Marcel TC, Montarry J, Morris CE, Omrani M, Paineau M, Perrot S, Pilet-Nayel M-L and Ruellan Y (2021) The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactions. bioRxiv, 2021.03.03.433745, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433745 Navarro, R., Ambros, S., Martinez, F., Wu, B., Carrasco, J. L., and Elena, S. F. (2020). Defects in plant immunity modulate the rates and patterns of RNA virus evolution. bioRxiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.13.337402 Valverde, S., Vidiella, B., Montañez, R., Fraile, A., Sacristán, S., and García-Arenal, F. (2020). Coexistence of nestedness and modularity in host–pathogen infection networks. Nature ecology & evolution, 4, 568-577. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1130-9 | The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactions | Moury Benoît, Audergon Jean-Marc, Baudracco-Arnas Sylvie, Ben Krima Safa, Bertrand François, Boissot Nathalie, Buisson Mireille, Caffier Valérie, Cantet Mélissa, Chanéac Sylvia, Constant Carole, Delmotte François, Dogimont Catherine, Doumayrou Jul... | <p>Understanding the relationships between host range and pathogenicity for parasites, and between the efficiency and scope of immunity for hosts are essential to implement efficient disease control strategies. In the case of plant parasites, most... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Species interactions | Santiago Elena | 2021-03-04 21:23:08 | View | |

18 Jan 2021

Trait plasticity and covariance along a continuous soil moisture gradientJ Grey Monroe, Haoran Cai, David L Des Marais https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.17.952853Another step towards grasping the complexity of the environmental response of traitsRecommended by Benoit Pujol based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersOne can only hope that one day, we will be able to evaluate how the ecological complexity surrounding natural populations affects their ability to adapt. This is more like a long term quest than a simple scientific aim. Many steps are heading in the right direction. This paper by Monroe and colleagues (2021) is one of them. References Gienapp P. & J.E. Brommer. 2014. Evolutionary dynamics in response to climate change. In: Charmentier A, Garant D, Kruuk LEB, editors. Quantitative genetics in the wild. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Oxford. pp. 254–273. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199674237.003.0015 | Trait plasticity and covariance along a continuous soil moisture gradient | J Grey Monroe, Haoran Cai, David L Des Marais | <p>Water availability is perhaps the greatest environmental determinant of plant yield and fitness. However, our understanding of plant-water relations is limited because it is primarily informed by experiments considering soil moisture variabilit... |  | Phenotypic Plasticity | Benoit Pujol | 2020-02-20 16:34:40 | View | |

20 Dec 2022

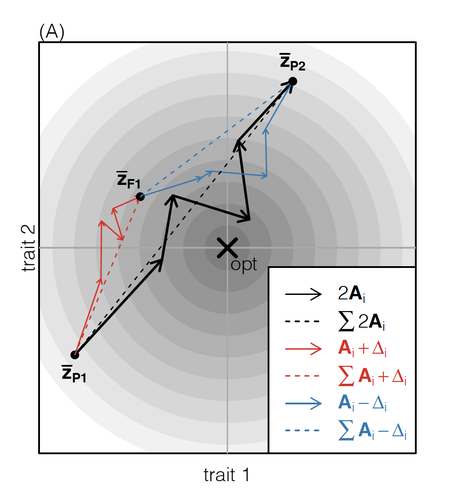

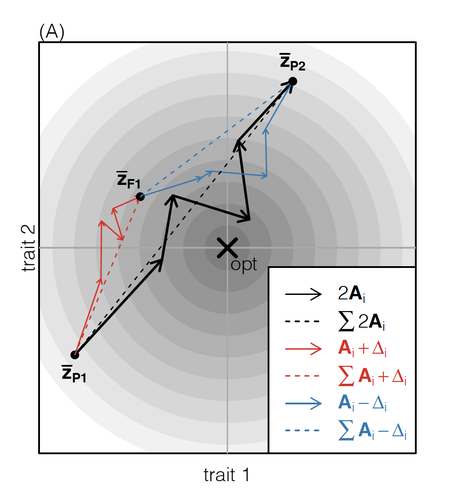

How does the mode of evolutionary divergence affect reproductive isolation?Bianca De Sanctis, Hilde Schneemann, John J. Welch https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.08.483443A general model of fitness effects following hybridisationRecommended by Matthew Hartfield based on reviews by Luis-Miguel Chevin and Juan LiStudying the effects of speciation, hybridisation, and evolutionary outcomes following reproduction from divergent populations is a major research area in evolutionary genetics [1]. There are two phenomena that have been the focus of contemporary research. First, a classic concept is the formation of ‘Bateson-Dobzhansky-Muller’ incompatibilities (BDMi) [2–4] that negatively affect hybrid fitness. Here, two diverging populations accumulate mutations over time that are unique to that subpopulation. If they subsequently meet, then these mutations might negatively interact, leading to a loss in fitness or even a complete lack of reproduction. BDMi formation can be complex, involving multiple genes and the fitness changes can depend on the direction of introgression [5]. Second, such secondary contact can instead lead to heterosis, where offspring are fitter than their parental progenitors [6]. Understanding which outcomes are likely to arise require one to know the potential fitness effects of mutations underlying reproductive isolation, to determine whether they are likely to reduce or enhance fitness when hybrids are formed. This is far from an easy task, as it requires one to track mutations at several loci, along with their effects, across a fitness landscape. The work of De Sanctis et al. [7] neatly fills in this knowledge gap, by creating a general mathematical framework for describing the consequences of a cross from two divergent populations. The derivations are based on Fisher’s Geometric Model, which is widely used to quantify selection acting on a general fitness landscape that is affected by several biological traits [8,9], and has previously been used in theoretical studies of hybridisation [10–12]. By doing so, they are able to decompose how divergence at multiple loci affects offspring fitness through both additive and dominance effects. A key result arising from their analyses is demonstrating how offspring fitness can be captured by two main functions. The first one is the ‘net effect of evolutionary change’ that, broadly defined, measures how phenotypically divergent two populations are. The second is the ‘total amount of evolutionary change’, which reflects how many mutations contribute to divergence and the effect sizes captured by each of them. The authors illustrate these measurements using simulations covering different scenarios, demonstrating how different parental states can lead to similar fitness outcomes. They also propose experimental methods to measure the underlying mutational effects. This study neatly demonstrates how complex genetic phenomena underlying hybridisation can be captured using fairly simple mathematical formulae. This powerful approach will thus open the door for future research to investigate hybridisation in more detail, whether it is by expanding on these theoretical models or using the elegant outcomes to quantify fitness effects in experiments.

References 1. Coyne JA, Orr HA. Speciation. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 2004. | How does the mode of evolutionary divergence affect reproductive isolation? | Bianca De Sanctis, Hilde Schneemann, John J. Welch | <p>When divergent populations interbreed, the outcome will be affected by the genomic and phenotypic differences that they have accumulated. In this way, the mode of evolutionary divergence between populations may have predictable consequences for... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Matthew Hartfield | 2022-03-30 14:55:46 | View | |

28 Aug 2019

Is adaptation limited by mutation? A timescale-dependent effect of genetic diversity on the adaptive substitution rate in animalsMarjolaine Rousselle, Paul Simion, Marie-Ka Tilak, Emeric Figuet, Benoit Nabholz, Nicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/643619To tinker, evolution needs a supply of spare partsRecommended by Georgii Bazykin based on reviews by Konstantin Popadin, David Enard and 1 anonymous reviewerIs evolution adaptive? Not if there is no variation for natural selection to work with. Theory predicts that how fast a population can adapt to a new environment can be limited by the supply of new mutations coming into it. This supply, in turn, depends on two things: how often mutations occur and in how many individuals. If there are few mutations, or few individuals in whom they can originate, individuals will be mostly identical in their DNA, and natural selection will be impotent. References [1] G, J. A., Visser, M. de, Zeyl, C. W., Gerrish, P. J., Blanchard, J. L., and Lenski, R. E. (1999). Diminishing Returns from Mutation Supply Rate in Asexual Populations. Science, 283(5400), 404–406. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.404 | Is adaptation limited by mutation? A timescale-dependent effect of genetic diversity on the adaptive substitution rate in animals | Marjolaine Rousselle, Paul Simion, Marie-Ka Tilak, Emeric Figuet, Benoit Nabholz, Nicolas Galtier | <p>Whether adaptation is limited by the beneficial mutation supply is a long-standing question of evolutionary genetics, which is more generally related to the determination of the adaptive substitution rate and its relationship with the effective... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Georgii Bazykin | 2019-05-21 09:49:16 | View | |

09 Nov 2018

Field evidence for manipulation of mosquito host selection by the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparumAmelie Vantaux, Franck Yao, Domonbabele FdS Hien, Edwige Guissou, Bienvenue K Yameogo, Louis-Clement Gouagna, Didier Fontenille, Francois Renaud, Frederic Simard, Carlo Constantini, Frederic Thomas, Karine Mouline, Benjamin Roche, Anna Cohuet, Kounbobr R Dabire, Thierry Lefevre https://doi.org/10.1101/207183Malaria host manipulation increases probability of mosquitoes feeding on humansRecommended by Alison Duncan based on reviews by Olivier Restif, Ricardo S. Ramiro and 1 anonymous reviewerParasites can manipulate their host’s behaviour to ensure their own transmission. These manipulated behaviours may be outside the range of ordinary host activities [1], or alter the crucial timing and/or location of a host’s regular activity. Vantaux et al show that the latter is true for the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum [2]. They demonstrate that three species of Anopheles mosquito were 24% more likely to choose human hosts, rather than other vertebrates, for their blood feed when they harboured transmissible stages (sporozoites) compared to when they were uninfected, or infected with non-transmissible malaria parasites [2]. Host choice is crucial for the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum to complete its life-cycle, as their host range is much narrower than the mosquito’s for feeding; P. falciparum can only develop in hominids, or closely related apes [3]. References [1] Thomas, F., Schmidt-Rhaesa, A., Martin, G., Manu, C., Durand, P., & Renaud, F. (2002). Do hairworms (Nematomorpha) manipulate the water seeking behaviour of their terrestrial hosts? Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 15(3), 356–361. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00410.x | Field evidence for manipulation of mosquito host selection by the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum | Amelie Vantaux, Franck Yao, Domonbabele FdS Hien, Edwige Guissou, Bienvenue K Yameogo, Louis-Clement Gouagna, Didier Fontenille, Francois Renaud, Frederic Simard, Carlo Constantini, Frederic Thomas, Karine Mouline, Benjamin Roche, Anna Cohuet, Kou... | <p>Whether the malaria parasite *Plasmodium falciparum* can manipulate mosquito host choice in ways that enhance parasite transmission toward human is unknown. We assessed the influence of *P. falciparum* on the blood-feeding behaviour of three of... |  | Evolutionary Ecology | Alison Duncan | 2018-02-28 09:12:14 | View | |

22 Jul 2019

Transgenerational plasticity of inducible defenses: combined effects of grand-parental, parental and current environmentsJuliette Tariel; Sandrine Plénet; Emilien Luquet https://doi.org/10.1101/589945Transgenerational plasticity through three generationsRecommended by Troy Day based on reviews by Stewart Plaistow and 1 anonymous reviewerOrganisms very often display phenotypic plasticity, whereby the expression of trait (or suite of traits) changes in a consistent way as a function of some environmental variable. Sometimes this plastic response remains labile and so the trait continues to respond to the environment throughout an organism’s life, but there are also many examples in which environmental conditions during a critical developmental window irreversibly set the stage for how a trait will be expressed later in life. References [1] West-Eberhard, M. J. (2003). Developmental plasticity and evolution. Oxford University Press. | Transgenerational plasticity of inducible defenses: combined effects of grand-parental, parental and current environments | Juliette Tariel; Sandrine Plénet; Emilien Luquet | <p>While an increasing number of studies highlights that parental environment shapes offspring phenotype (transgenerational plasticity TGP), TGP beyond the parental generation has received less attention. Studies suggest that TGP impacts populatio... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Non Genetic Inheritance, Phenotypic Plasticity | Troy Day | 2019-03-29 09:31:53 | View | |

05 Feb 2021

Relaxation of purifying selection suggests low effective population size in eusocial Hymenoptera and solitary pollinating beesArthur Weyna, Jonathan Romiguier https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.14.038893Multi-gene and lineage comparative assessment of the strength of selection in HymenopteraRecommended by Bertanne Visser based on reviews by Michael Lattorff and 1 anonymous reviewerGenetic variation is the raw material for selection to act upon and the amount of genetic variation present within a population is a pivotal determinant of a population’s evolutionary potential. A large effective population size, i.e., the ideal number of individuals experiencing the same amount of genetic drift and inbreeding as an actual population, Ne (Wright 1931, Crow 1954), thus increases the probability of long-term survival of a population. However, natural populations, as opposed to theoretical ones, rarely adhere to the requirements of an ideal panmictic population (Sjödin et al. 2005). A range of circumstances can reduce Ne, including the structuring of populations (through space and time, as well as age and developmental stages) and inbreeding (Charlesworth 2009). In mammals, species with a larger body mass (as a proxy for lower Ne) were found to have a higher rate of nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions (that alter the amino acid sequence of a protein), as well as radical amino acid substitutions (altering the physicochemical properties of a protein) (Popadin et al. 2007). In general, low effective population sizes increase the chance of mutation accumulation and drift, while reducing the strength of selection (Sjödin et al. 2005). References Charlesworth, B. (2009). Effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation. Nature Reviews Genetics, 10(3), 195-205. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2526 | Relaxation of purifying selection suggests low effective population size in eusocial Hymenoptera and solitary pollinating bees | Arthur Weyna, Jonathan Romiguier | <p>With one of the highest number of parasitic, eusocial and pollinator species among all insect orders, Hymenoptera features a great diversity of lifestyles. At the population genetic level, such life-history strategies are expected to decrease e... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Genome Evolution, Life History, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Bertanne Visser | 2020-04-21 17:30:57 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer