Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▲ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

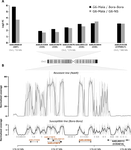

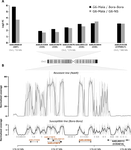

05 Nov 2020

A genomic amplification affecting a carboxylesterase gene cluster confers organophosphate resistance in the mosquito Aedes aegypti: from genomic characterization to high-throughput field detectionJulien Cattel, Chloé Haberkorn, Fréderic Laporte, Thierry Gaude, Tristan Cumer, Julien Renaud, Ian W. Sutherland, Jeffrey C. Hertz, Jean-Marc Bonneville, Victor Arnaud, Camille Noûs, Bénédicte Fustec, Sébastien Boyer, Sébastien Marcombe, Jean-Philippe David https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.139741Identification of a gene cluster amplification associated with organophosphate insecticide resistance: from the diversity of the resistance allele complex to an efficient field detection assayRecommended by Stephanie Bedhomme based on reviews by Diego Ayala and 2 anonymous reviewersThe emergence and spread of insecticide resistance compromises the efficiency of insecticides as prevention tool against the transmission of insect-transmitted diseases (Moyes et al. 2017). In this context, the understanding of the genetic mechanisms of resistance and the way resistant alleles spread in insect populations is necessary and important to envision resistance management policies. A common and important mechanism of insecticide resistance is gene amplification and in particular amplification of insecticide detoxification genes, which leads to the overexpression of these genes (Bass & Field, 2011). Cattel and coauthors (2020) adopt a combination of experimental approaches to study the role of gene amplification in resistance to organophosphate insecticides in the mosquito Aedes aegypti and its occurrence in populations of South East Asia and to develop a molecular test to track resistance alleles. References Bass C, Field LM (2011) Gene amplification and insecticide resistance. Pest Management Science, 67, 886–890. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2189 | A genomic amplification affecting a carboxylesterase gene cluster confers organophosphate resistance in the mosquito Aedes aegypti: from genomic characterization to high-throughput field detection | Julien Cattel, Chloé Haberkorn, Fréderic Laporte, Thierry Gaude, Tristan Cumer, Julien Renaud, Ian W. Sutherland, Jeffrey C. Hertz, Jean-Marc Bonneville, Victor Arnaud, Camille Noûs, Bénédicte Fustec, Sébastien Boyer, Sébastien Marcombe, Jean-Phil... | <p>By altering gene expression and creating paralogs, genomic amplifications represent a key component of short-term adaptive processes. In insects, the use of insecticides can select gene amplifications causing an increased expression of detoxifi... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Experimental Evolution, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Stephanie Bedhomme | 2020-06-09 13:27:18 | View | |

03 Apr 2020

Evolution at two time-frames: ancient and common origin of two structural variants involved in local adaptation of the European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa)Alan Le Moan, Dorte Bekkevold & Jakob Hemmer-Hansen https://doi.org/10.1101/662577Genomic structural variants involved in local adaptation of the European plaiceRecommended by Maren Wellenreuther based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersAwareness has been growing that structural variants in the genome of species play a fundamental role in adaptive evolution and diversification [1]. Here, Le Moan and co-authors [2] report empirical genomic-wide SNP data on the European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) across a major environmental transmission zone, ranging from the North Sea to the Baltic Sea. Regions of high linkage disequilibrium suggest the presence of two structural variants that appear to have evolved 220 kya. These two putative structural variants show weak signatures of isolation by distance when contrasted against the rest of the genome, but the frequency of the different putative structural variants appears to co-vary in some parts of the studied range with the environment, indicating the involvement of both selective and neutral processes. This study adds to the mounting body of evidence that structural genomic variants harbour significant information that allows species to respond and adapt to the local environmental context. References [1] Wellenreuther, M., Mérot, C., Berdan, E., & Bernatchez, L. (2019). Going beyond SNPs: the role of structural genomic variants in adaptive evolution and species diversification. Molecular ecology, 28(6), 1203-1209. doi: 10.1111/mec.15066 | Evolution at two time-frames: ancient and common origin of two structural variants involved in local adaptation of the European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) | Alan Le Moan, Dorte Bekkevold & Jakob Hemmer-Hansen | <p>Changing environmental conditions can lead to population diversification through differential selection on standing genetic variation. Structural variant (SV) polymorphisms provide examples of ancient alleles that in time become associated with... | Adaptation, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Maren Wellenreuther | 2019-07-13 12:44:01 | View | ||

11 Jun 2019

A bird’s white-eye view on neosex chromosome evolutionThibault Leroy, Yoann Anselmetti, Marie-Ka Tilak, Sèverine Bérard, Laura Csukonyi, Maëva Gabrielli, Céline Scornavacca, Borja Milá, Christophe Thébaud, Benoit Nabholz https://doi.org/10.1101/505610Young sex chromosomes discovered in white-eye birdsRecommended by Kateryna Makova based on reviews by Gabriel Marais, Melissa Wilson and 1 anonymous reviewerRecent advances in next-generation sequencing are allowing us to uncover the evolution of sex chromosomes in non-model organisms. This study [1] represents an example of this application to birds of two Sylvioidea species from the genus Zosterops (commonly known as white-eyes). The study is exemplary in the amount and types of data generated and in the thoroughness of the analysis applied. Both male and female genomes were sequenced to allow the authors to identify sex-chromosome specific scaffolds. These data were augmented by generating the transcriptome (RNA-seq) data set. The findings after the analysis of these extensive data are intriguing: neoZ and neoW chromosome scaffolds and their breakpoints were identified. Novel sex chromosome formation appears to be accompanied by translocation events. The timing of formation of novel sex chromosomes was identified using molecular dating and appears to be relatively recent. Yet first signatures of distinct evolutionary patterns of sex chromosomes vs. autosomes could be already identified. These include the accumulation of transposable elements and changes in GC content. The changes in GC content could be explained by biased gene conversion and altered recombination landscape of the neo sex chromosomes. The authors also study divergence and diversity of genes located on the neo sex chromosomes. Here their findings appear to be surprising and need further exploration. The neoW chromosome already shows unique patterns of divergence and diversity at protein-coding genes as compared with genes on either neoZ or autosomes. In contrast, the genes on the neoZ chromosome do not display divergence or diversity patterns different from those for autosomes. This last observation is puzzling and I believe should be explored in further studies. Overall, this study significantly advances our knowledge of the early stages of sex chromosome evolution in vertebrates, provides an example of how such a study could be conducted in other non-model organisms, and provides several avenues for future work. References [1] Leroy T., Anselmetti A., Tilak M.K., Bérard S., Csukonyi L., Gabrielli M., Scornavacca C., Milá B., Thébaud C. and Nabholz B. (2019). A bird’s white-eye view on neo-sex chromosome evolution. bioRxiv, 505610, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/505610 | A bird’s white-eye view on neosex chromosome evolution | Thibault Leroy, Yoann Anselmetti, Marie-Ka Tilak, Sèverine Bérard, Laura Csukonyi, Maëva Gabrielli, Céline Scornavacca, Borja Milá, Christophe Thébaud, Benoit Nabholz | <p>Chromosomal organization is relatively stable among avian species, especially with regards to sex chromosomes. Members of the large Sylvioidea clade however have a pair of neo-sex chromosomes which is unique to this clade and originate from a p... |  | Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Kateryna Makova | 2019-01-24 14:17:15 | View | |

26 Sep 2017

Lacking conservation genomics in the giant Galápagos tortoiseEtienne Loire, Nicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/101980A genomic perspective is needed for the re-evaluation of species boundaries, evolutionary trajectories and conservation strategies for the Galápagos giant tortoisesRecommended by Michael C. Fontaine based on reviews by 4 anonymous reviewersGenome-wide data obtained from even a small number of individuals can provide unprecedented levels of detail about the evolutionary history of populations and species [1], determinants of genetic diversity [2], species boundaries and the process of speciation itself [3]. Loire and Galtier [4] present a clear example, using the emblematic Galápagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis nigra), of how multi-species comparative population genomic approaches can provide valuable insights about population structure and species delimitation even when sample sizes are limited but the number of loci is large and distributed across the genome. Galápagos giant tortoises are endemic to the Galápagos Islands and are currently recognized as an endangered, multi-species complex including both extant and extinct taxa. Taxonomic definitions are based on morphology, geographic isolation and population genetic evidence based on short DNA sequences of the mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) and/or a dozen or so nuclear microsatellite loci [5-8]. The species complex enjoys maximal protection. Population recoveries have been quite successful and spectacular conservation programs based on mitochondrial genes and microsatellites are ongoing. This includes for example individual translocations, breeding program, “hybrid” sterilization or removal, and resurrection of extinct lineages). In 2013, Loire et al. [9] provided the first population genomic analyses based on genome scale data (~1000 coding loci derived from blood-transcriptomes) from five individuals, encompassing three putative “species”: Chelonnoidis becki, C. porteri and C. vandenburghi. Their results raised doubts about the validity/accuracy of the currently accepted designations of “genetic distinctiveness”. However, the implications for conservation and management have remained unnoticed. In 2017, Loire and Galtier [4] have re-appraised this issue using an original multi-species comparative population genomic analysis of their previous data set [9]. Based on a comparison of 53 animal species, they show that both the level of genome-wide neutral diversity (πS) and level of population structure estimated using the inbreeding coefficient (F) are much lower than would be expected from a sample covering multiple species. The observed values are more comparable to those typically reported at the “among population” level within a single species such as human (Homo sapiens). The authors go to great length to assess the sensitivity of their method to detect population structure (or lack thereof) and show that their results are robust to potential issues, such as contamination and sequencing errors that can occur with Next Generation Sequencing techniques; and biases related to the small sample size and sub-sampling of individuals. They conclude that published mtDNA and microsatellite-based assessment of population structure and species designations may be biased towards over-splitting. This manuscript is a very good read as it shows the potential of the now relatively affordable genome-wide data for helping to both resolve and clarify population and species boundaries, illuminate demographic trends, evolutionary trajectories of isolated groups, patterns of connectivity among them, and test for evidence of local adaptation and even reproductive isolation. The comprehensive information provided by genome-wide data can critically inform and assist the development of the best strategies to preserve endangered populations and species. Loire and Galtier [4] make a strong case for applying genomic data to the Galápagos giant tortoises, which is likely to redirect conservation efforts more effectively and at lower cost. The case of the Galápagos giant tortoises is certainly a very emblematic example, which will find an echo in many other endangered species conservation programs. References [1] Li H and Durbin R. 2011. Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature, 475: 493–496. doi: 10.1038/nature10231 [2] Romiguier J, Gayral P, Ballenghien M, Bernard A, Cahais V, Chenuil A, Chiari Y, Dernat R, Duret L, Faivre N, Loire E, Lourenco JM, Nabholz B, Roux C, Tsagkogeorga G, Weber AA-T, Weinert LA, Belkhir K, Bierne N, Glémin S and Galtier N. 2014. Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature, 515: 261–263. doi: 10.1038/nature13685 [3] Roux C, Fraïsse C, Romiguier J, Anciaux Y, Galtier N and Bierne N. 2016. Shedding light on the grey zone of speciation along a continuum of genomic divergence. PLoS Biology, 14: e2000234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2000234 [4] Loire E and Galtier N. 2017. Lacking conservation genomics in the giant Galápagos tortoise. bioRxiv 101980, ver. 4 of September 26, 2017. doi: 10.1101/101980 [5] Beheregaray LB, Ciofi C, Caccone A, Gibbs JP and Powell JR. 2003. Genetic divergence, phylogeography and conservation units of giant tortoises from Santa Cruz and Pinzón, Galápagos Islands. Conservation Genetics, 4: 31–46. doi: 10.1023/A:1021864214375 [6] Ciofi C, Milinkovitch MC, Gibbs JP, Caccone A and Powell JR. 2002. Microsatellite analysis of genetic divergence among populations of giant Galápagos tortoises. Molecular Ecology, 11: 2265–2283. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01617.x [7] Garrick RC, Kajdacsi B, Russello MA, Benavides E, Hyseni C, Gibbs JP, Tapia W and Caccone A. 2015. Naturally rare versus newly rare: demographic inferences on two timescales inform conservation of Galápagos giant tortoises. Ecology and Evolution, 5: 676–694. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1388 [8] Poulakakis N, Edwards DL, Chiari Y, Garrick RC, Russello MA, Benavides E, Watkins-Colwell GJ, Glaberman S, Tapia W, Gibbs JP, Cayot LJ and Caccone A. 2015. Description of a new Galápagos giant tortoise species (Chelonoidis; Testudines: Testudinidae) from Cerro Fatal on Santa Cruz island. PLoS ONE, 10: e0138779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138779 [9] Loire E, Chiari Y, Bernard A, Cahais V, Romiguier J, Nabholz B, Lourenço JM and Galtier N. 2013. Population genomics of the endangered giant Galápagos tortoise. Genome Biology, 14: R136. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-12-r136 | Lacking conservation genomics in the giant Galápagos tortoise | Etienne Loire, Nicolas Galtier | <p>Conservation policy in the giant Galápagos tortoise, an iconic endangered animal, has been assisted by genetic markers for ~15 years: a dozen loci have been used to delineate thirteen (sub)species, between which hybridization is prevented. Here... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation, Systematics / Taxonomy | Michael C. Fontaine | 2017-01-21 15:34:00 | View | |

21 Nov 2018

Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infectionFrederic Bertels, Karin J Metzner, Roland R Regoes https://doi.org/10.1101/168260Is convergence an evidence for positive selection?Recommended by Guillaume Achaz based on reviews by Jeffrey Townsend and 1 anonymous reviewerThe preprint by Bertels et al. [1] reports an interesting application of the well-accepted idea that positively selected traits (here variants) can appear several times independently; think about the textbook examples of flight capacity. Hence, the authors assume that reciprocally convergence implies positive selection. The methodology becomes then, in principle, straightforward as one can simply count variants in independent datasets to detect convergent mutations. References [1] Bertels, F., Metzner, K. J., & Regoes R. R. (2018). Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infection. BioRxiv, 168260, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/168260 | Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infection | Frederic Bertels, Karin J Metzner, Roland R Regoes | <p>Convergent evolution describes the process of different populations acquiring similar phenotypes or genotypes. Complex organisms with large genomes only rarely and only under very strong selection converge to the same genotype. In contrast, ind... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Guillaume Achaz | 2017-07-26 08:39:17 | View | |

09 Dec 2019

Systematics and geographical distribution of Galba species, a group of cryptic and worldwide freshwater snailsPilar Alda, Manon Lounnas, Antonio Alejandro Vázquez, Rolando Ayaqui, Manuel Calvopina, Maritza Celi-Erazo, Robert Dillon, Luisa Carolina González Ramírez, Eric S. Loker, Jenny Muzzio-Aroca, Alberto Orlando Nárvaez, Oscar Noya, Andrés Esteban Pereira, Luiggi Martini Robles, Richar Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Nelson Uribe, Patrice David, Philippe Jarne, Jean-Pierre Pointier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès https://doi.org/10.1101/647867The challenge of delineating species when they are hiddenRecommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by Pavel Matos, Christelle Fraïsse and Niklas WahlbergThe science of naming species (taxonomy) has been renewed with the developments of molecular sequencing, digitization of museum specimens, and novel analytical tools. However, naming species can be highly subjective, sometimes considered as an art [1], because it is based on human-based criteria that vary among taxonomists. Nonetheless, taxonomists often argue that species names are hypotheses, which are therefore testable and refutable as new evidence is provided. This challenge comes with a more and more recognized and critical need for rigorously delineated species not only for producing accurate species inventories, but more importantly many questions in evolutionary biology (e.g. speciation), ecology (e.g. ecosystem structure and functioning), conservation biology (e.g. targeting priorities) or biogeography (e.g. diversification processes) depend in part on those species inventories and our knowledge of species [2-3]. Inaccurate species boundaries or diversity estimates may lead us to deliver biased answers to those questions, exactly as phylogenetic trees must be reconstructed rigorously and analyzed critically because they are a first step toward discussing broader questions [2-3]. In this context, biological diversity needs to be studied from multiple and complementary perspectives requiring the collaboration of morphologists, molecular biologists, biogeographers, and modelers [4-5]. Integrative taxonomy has been proposed as a solution to tackle the challenge of delimiting species [2], especially in highly diverse and undocumented groups of organisms. References [1] Ohl, M. (2018). The art of naming. MIT Press. | Systematics and geographical distribution of Galba species, a group of cryptic and worldwide freshwater snails | Pilar Alda, Manon Lounnas, Antonio Alejandro Vázquez, Rolando Ayaqui, Manuel Calvopina, Maritza Celi-Erazo, Robert Dillon, Luisa Carolina González Ramírez, Eric S. Loker, Jenny Muzzio-Aroca, Alberto Orlando Nárvaez, Oscar Noya, Andrés Esteban Pere... | <p>Cryptic species can present a significant challenge to the application of systematic and biogeographic principles, especially if they are invasive or transmit parasites or pathogens. Detecting cryptic species requires a pluralistic approach in ... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Systematics / Taxonomy | Fabien Condamine | Pavel Matos, Christelle Fraïsse | 2019-05-25 10:34:57 | View |

20 Jan 2020

A young age of subspecific divergence in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria, inferred by ABC Random ForestMarie-Pierre Chapuis, Louis Raynal, Christophe Plantamp, Christine N. Meynard, Laurence Blondin, Jean-Michel Marin, Arnaud Estoup https://doi.org/10.1101/671867Estimating recent divergence history: making the most of microsatellite data and Approximate Bayesian Computation approachesRecommended by Takeshi Kawakami and Concetta Burgarella based on reviews by Michael D Greenfield and 2 anonymous reviewersThe present-day distribution of extant species is the result of the interplay between their past population demography (e.g., expansion, contraction, isolation, and migration) and adaptation to the environment. Shedding light on the timing and magnitude of key demographic events helps identify potential drivers of such events and interaction of those drivers, such as life history traits and past episodes of environmental shifts. The understanding of the key factors driving species evolution gives important insights into how the species may respond to changing conditions, which can be particularly relevant for the management of harmful species, such as agricultural pests (e.g. [1]). Meaningful demographic inferences present major challenges. These include formulating evolutionary scenarios fitting species biology and the eco-geographical context and choosing informative molecular markers and accurate quantitative approaches to statistically compare multiple demographic scenarios and estimate the parameters of interest. A further issue comes with result interpretation. Accurately dating the inferred events is far from straightforward since reliable calibration points are necessary to translate the molecular estimates of the evolutionary time into absolute time units (i.e. years). This can be attempted in different ways, such as by using fossil and archaeological records, heterochronous samples (e.g. ancient DNA), and/or mutation rate estimated from independent data (e.g. [2], [3] for review). Nonetheless, most experimental systems rarely meet these conditions, hindering the comprehensive interpretation of results. The contribution of Chapuis et al. [4] addresses these issues to investigate the recent history of the African insect pest Schistocerca gregaria (desert locust). They apply Approximate Bayesian Computation-Random Forest (ABC-RF) approaches to microsatellite markers. Owing to their fast mutation rate microsatellite markers offer at least two advantages: i) suitability for analyzing recently diverged populations, and ii) direct estimate of the germline mutation rate in pedigree samples. The work of Chapuis et al. [4] benefits of both these advantages, since they have estimates of mutation rate and allele size constraints derived from germline mutations in the species [5]. The main aim of the study is to infer the history of divergence of the two subspecies of the desert locust, which have spatially disjoint distribution corresponding to the dry regions of North and West-South Africa. They first use paleo-vegetation maps to formulate hypotheses about changes in species range since the last glacial maximum. Based on them, they generate 12 divergence models. For the selection of the demographic model and parameter estimation, they apply the recently developed ABC-RF approach, a powerful inferential tool that allows optimizing the use of summary statistics information content, among other advantages [6]. Some methodological novelties are also introduced in this work, such as the computation of the error associated with the posterior parameter estimates under the best scenario. The accuracy of timing estimate is assured in two ways: i) by the use of microsatellite markers with known evolutionary dynamics, as underlined above, and ii) by assessing the divergence time threshold above which posterior estimates are likely to be biased by size homoplasy and limits in allele size range [7]. The best-supported model suggests a recent divergence event of the subspecies of S. gregaria (around 2.6 kya) and a reduction of populations size in one of the subspecies (S. g. flaviventris) that colonized the southern distribution area. As such, results did not support the hypothesis that the southward colonization was driven by the expansion of African dry environments associated with the last glacial maximum, as it has been postulated for other arid-adapted species with similar African disjoint distributions [8]. The estimated time of divergence points at a much more recent origin for the two subspecies, during the late Holocene, in a period corresponding to fairly stable arid conditions similar to current ones [9,10]. Although the authors cannot exclude that their microsatellite data bear limited information on older colonization events than the last one, they bring arguments in favour of alternative explanations. The hypothesis privileged does not involve climatic drivers, but the particularly efficient dispersal behaviour of the species, whose individuals are able to fly over long distances (up to thousands of kilometers) under favourable windy conditions. A single long-distance dispersal event by a few individuals would explain the genetic signature of the bottleneck. There is a growing number of studies in phylogeography in arid regions in the Southern hemisphere, but the impact of past climate changes on the species distribution in this region remains understudied relative to the Northern hemisphere [11,12]. The study presented by Chapuis et al. [4] offers several important insights into demographic changes and the evolutionary history of an agriculturally important pest species in Africa, which could also mirror the history of other organisms in the continent. As the authors point out, there are necessarily some uncertainties associated with the models of past ecosystems and climate, especially for Africa. Interestingly, the authors argue that the information on paleo-vegetation turnover was more informative than climatic niche modeling for the purpose of their study since it made them consider a wider range of bio-geographical changes and in turn a wider range of evolutionary scenarios (see discussion in Supplementary Material). Microsatellite markers have been offering a useful tool in population genetics and phylogeography for decades, but their popularity is perhaps being taken over by single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) (the peak year of the number of the publication with “microsatellite” is in 2012 according to PubMed). This study reaffirms the usefulness of these classic molecular markers to estimate past demographic events, especially when species- and locus-specific microsatellite mutation features are available and a powerful inferential approach is adopted. Nonetheless, there are still hurdles to overcome, such as the limitations in scenario choice associated with the simulation software used (e.g. not allowing for continuous gene flow in this particular case), which calls for further improvement of simulation tools allowing for more flexible modeling of demographic events and mutation patterns. In sum, this work not only contributes to our understanding of the makeup of the African biodiversity but also offers a useful statistical framework, which can be applied to a wide array of species and molecular markers (microsatellites, SNPs, and WGS). References [1] Lehmann, P. et al. (2018). Complex responses of global insect pests to climate change. bioRxiv, 425488. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1101/425488 [2] Donoghue, P. C., & Benton, M. J. (2007). Rocks and clocks: calibrating the Tree of Life using fossils and molecules. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 22(8), 424-431. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2007.05.005 [3] Ho, S. Y., Lanfear, R., Bromham, L., Phillips, M. J., Soubrier, J., Rodrigo, A. G., & Cooper, A. (2011). Time‐dependent rates of molecular evolution. Molecular ecology, 20(15), 3087-3101. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05178.x [4] Chapuis, M.-P., Raynal, L., Plantamp, C., Meynard, C. N., Blondin, L., Marin, J.-M. and Estoup, A. (2020). A young age of subspecific divergence in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria, inferred by ABC Random Forest. bioRxiv, 671867, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1101/671867 5] Chapuis, M.-P., Plantamp, C., Streiff, R., Blondin, L., & Piou, C. (2015). Microsatellite evolutionary rate and pattern in Schistocerca gregaria inferred from direct observation of germline mutations. Molecular ecology, 24(24), 6107-6119. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/mec.13465 [6] Raynal, L., Marin, J. M., Pudlo, P., Ribatet, M., Robert, C. P., & Estoup, A. (2018). ABC random forests for Bayesian parameter inference. Bioinformatics, 35(10), 1720-1728. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty867 [7] Estoup, A., Jarne, P., & Cornuet, J. M. (2002). Homoplasy and mutation model at microsatellite loci and their consequences for population genetics analysis. Molecular ecology, 11(9), 1591-1604. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01576.x [8] Moodley, Y. et al. (2018). Contrasting evolutionary history, anthropogenic declines and genetic contact in the northern and southern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum). Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 285(1890), 20181567. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.1567 [9] Kröpelin, S. et al. (2008). Climate-driven ecosystem succession in the Sahara: the past 6000 years. science, 320(5877), 765-768. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1154913 [10] Maley, J. et al. (2018). Late Holocene forest contraction and fragmentation in central Africa. Quaternary Research, 89(1), 43-59. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/qua.2017.97 [11] Beheregaray, L. B. (2008). Twenty years of phylogeography: the state of the field and the challenges for the Southern Hemisphere. Molecular Ecology, 17(17), 3754-3774. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03857.x [12] Dubey, S., & Shine, R. (2012). Are reptile and amphibian species younger in the Northern Hemisphere than in the Southern Hemisphere?. Journal of evolutionary biology, 25(1), 220-226. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02417.x ***** A video about this preprint is available here: | A young age of subspecific divergence in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria, inferred by ABC Random Forest | Marie-Pierre Chapuis, Louis Raynal, Christophe Plantamp, Christine N. Meynard, Laurence Blondin, Jean-Michel Marin, Arnaud Estoup | <p>Dating population divergence within species from molecular data and relating such dating to climatic and biogeographic changes is not trivial. Yet it can help formulating evolutionary hypotheses regarding local adaptation and future responses t... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Takeshi Kawakami | 2019-06-20 10:31:15 | View | |

10 Jan 2020

Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shiftsGilles Didier https://doi.org/10.1101/376756Fitting diversification models on undated or partially dated treesRecommended by Nicolas Lartillot based on reviews by Amaury Lambert, Dominik Schrempf and 1 anonymous reviewerPhylogenetic trees can be used to extract information about the process of diversification that has generated them. The most common approach to conduct this inference is to rely on a likelihood, defined here as the probability of generating a dated tree T given a diversification model (e.g. a birth-death model), and then use standard maximum likelihood. This idea has been explored extensively in the context of the so-called diversification studies, with many variants for the models and for the questions being asked (diversification rates shifting at certain time points or in the ancestors of particular subclades, trait-dependent diversification rates, etc). References [1] Didier, G. (2020) Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shifts. bioRxiv, 376756, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/376756 | Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shifts | Gilles Didier | <p>Dating the tree of life is a task far more complicated than only determining the evolutionary relationships between species. It is therefore of interest to develop approaches apt to deal with undated phylogenetic trees. The main result of this ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Macroevolution | Nicolas Lartillot | 2019-01-30 11:28:58 | View | |

16 Nov 2022

Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in miceCarole M. Smadja, Etienne Loire, Pierre Caminade, Dany Severac, Mathieu Gautier, Guila Ganem https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.21.500634Tinder in mice: A match made with the sense of smellRecommended by Christelle Fraïsse based on reviews by Angeles de Cara, Ludovic Claude Maisonneuve and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Angeles de Cara, Ludovic Claude Maisonneuve and 1 anonymous reviewer

Differentiation-based genome scans lie at the core of speciation and adaptation genomics research. Dating back to Lewontin & Krakauer (1973), they have become very popular with the advent of genomics to identify genome regions of enhanced differentiation relative to neutral expectations. These regions may represent genetic barriers between divergent lineages and are key for studying reproductive isolation. However, genome scan methods can generate a high rate of false positives, primarily if the neutral population structure is not accounted for (Bierne et al. 2013). Moreover, interpreting genome scans can be challenging in the context of secondary contacts between diverging lineages (Bierne et al. 2011), because the coupling between different components of reproductive isolation (local adaptation, intrinsic incompatibilities, mating preferences, etc.) can occur readily, thus preventing the causes of differentiation from being determined. Smadja and collaborators (2022) applied a sophisticated genome scan for trait association (BAYPASS, Gautier 2015) to underlie the genetic basis of a polygenetic behaviour: assortative mating in hybridizing mice. My interest in this neat study mainly relies on two reasons. First, the authors used an ingenious geographical setting (replicate pairs of “Choosy” versus “Non-Choosy” populations) with multi-way comparisons to narrow down the list of candidate regions resulting from BAYPASS. The latter corrects for population structure, handles cost-effective pool-seq data and allows for gene-based analyses that aggregate SNP signals within a gene. These features reinforce the set of outlier genes detected; however, not all are expected to be associated with mating preference. The second reason why this study is valuable to me is that Smadja et al. (2022) complemented the population genomic approach with functional predictions to validate the genetic signal. In line with previous behavioural and chemical assays on the proximal mechanisms of mating preferences, they identified multiple olfactory and vomeronasal receptor genes as highly significant candidates. Therefore, combining genomic signals with functional analyses is a clever way to provide insights into the causes of reproductive isolation, especially when multiple barriers are involved. This is typically true for reinforcement (Butlin & Smadja 2018), suspected to occur in these mice because, in that case, assortative mating (a prezygotic barrier) evolves in response to the cost of hybridization (for example, due to hybrid inviability). As advocated by the authors, their study paves the way for future work addressing the genetic basis of reinforcement, a trait of major evolutionary importance for which we lack empirical data. They also make a compelling case using complementary approaches that olfactory and vomeronasal receptors have a central role in mammal speciation.

Bierne N, Welch J, Loire E, Bonhomme F, David P (2011) The coupling hypothesis: why genome scans may fail to map local adaptation genes. Mol Ecol 20: 2044–2072. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05080.x Bierne N, Roze D, Welch JJ (2013) Pervasive selection or is it…? why are FST outliers sometimes so frequent? Mol Ecol 22: 2061–2064. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12241 Butlin RK, Smadja CM (2018) Coupling, Reinforcement, and Speciation. Am Nat 191:155–172. https://doi.org/10.1086/695136 Gautier M (2015) Genome-Wide Scan for Adaptive Divergence and Association with Population-Specific Covariates. Genetics 201:1555–1579. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.115.181453 Lewontin RC, Krakauer J (1973) Distribution of gene frequency as a test of the theory of selective neutrality of polymorphisms. Genetics 74: 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/74.1.175 Smadja CM, Loire E, Caminade P, Severac D, Gautier M, Ganem G (2022) Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in mice. bioRxiv, 2022.07.21.500634, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.21.500634 | Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in mice | Carole M. Smadja, Etienne Loire, Pierre Caminade, Dany Severac, Mathieu Gautier, Guila Ganem | <p>Deciphering the genetic bases of behavioural traits is essential to understanding how they evolve and contribute to adaptation and biological diversification, but it remains a substantial challenge, especially for behavioural traits with polyge... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Speciation | Christelle Fraïsse | 2022-07-25 11:54:52 | View | |

05 Aug 2020

Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognitaDjampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.30.069948DNA transposons drive genome evolution of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognitaRecommended by Ines Alvarez based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers

Duplications, mutations and recombination may be considered the main sources of genomic variation and evolution. In addition, sexual recombination is essential in purging deleterious mutations and allowing advantageous allelic combinations to occur (Glémin et al. 2019). However, in parthenogenetic asexual organisms, variation cannot be explained by sexual recombination, and other mechanisms must account for it. Although it is known that transposable elements (TE) may influence on genome structure and gene expression patterns, their role as a primary source of genomic variation and rapid adaptability has received less attention. An important role of TE on adaptive genome evolution has been documented for fungal phytopathogens (Faino et al. 2016), suggesting that TE activity might explain the evolutionary dynamics of this type of organisms. References [1] Bessereau J-L. 2006. Transposons in C. elegans. WormBook. 10.1895/wormbook.1.70.1 | Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita | Djampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin | <p>Despite reproducing without sexual recombination, the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita is adaptive and versatile. Indeed, this species displays a global distribution, is able to parasitize a large range of plants and can overcome plant ... | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Ines Alvarez | 2020-05-04 11:43:14 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer