Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

08 Feb 2019

Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenesAnouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo https://doi.org/10.1101/337477E5, the third oncogene of PapillomavirusRecommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Leonardo de Oliveira Martins and 1 anonymous reviewerPapillomaviruses (PVs) infect almost all mammals and possibly amniotes and bony fishes. While most of them have no significant effects on the hosts, some induce physical lesions. Phylogeny of PVs consists of a few crown groups [1], among which AlphaPVs that infect primates including human have been well studied. They are associated to largely different clinical manifestations: non-oncogenic PVs causing anogenital warts, oncogenic and non-oncogenic PVs causing mucosal lesions, and non-oncogenic PVs causing cutaneous warts. References [1] Bravo, I. G., & Alonso, Á. (2004). Mucosal human papillomaviruses encode four different E5 proteins whose chemistry and phylogeny correlate with malignant or benign growth. Journal of virology, 78, 13613-13626. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13613-13626.2004 | Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenes | Anouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo | <p>The clinical presentations of papillomavirus (PV) infections come in many different flavors. While most PVs are part of a healthy skin microbiota and are not associated to physical lesions, other PVs cause benign lesions, and only a handful of ... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Hirohisa Kishino | 2018-06-04 16:15:39 | View | |

14 Feb 2024

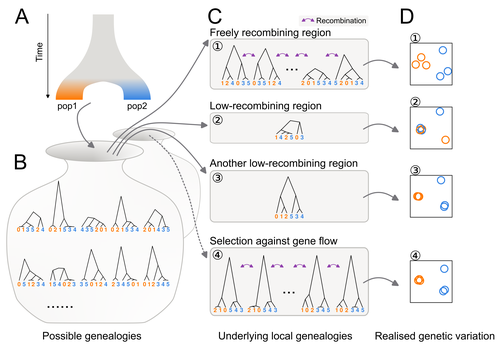

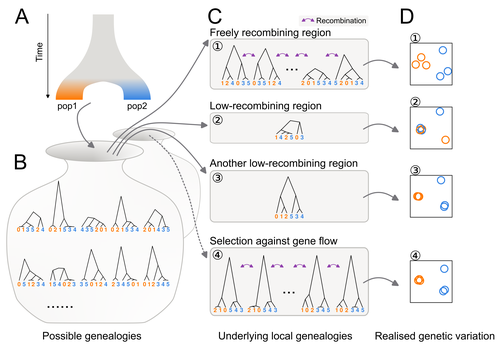

Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structureJun Ishigohoka, Karen Bascón-Cardozo, Andrea Bours, Janina Fuß, Arang Rhie, Jacquelyn Mountcastle, Bettina Haase, William Chow, Joanna Collins, Kerstin Howe, Marcela Uliano-Silva, Olivier Fedrigo, Erich D. Jarvis, Javier Pérez-Tris, Juan Carlos Illera, Miriam Liedvogel https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.22.473882Discerning the causes of local deviations in genetic variation: the effect of low-recombination regionsRecommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Claire Merot and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Claire Merot and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this study, Ishigohoka and colleagues tackle an important, yet often overlooked, question on the causes of genetic variation. While genome-wide patterns represent population structure, local variation is often associated with selection. Authors propose that an alternative cause for variation in individual loci is reduced recombination rate. To test this hypothesis, authors perform local Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (Li & Ralph, 2019) to identify local deviations in population structure in the Eurasian blackcap (Sylvia atricapilla) (Ishigohoka et al. 2022). This approach is typically used to detect chromosomal rearrangements or any long region of linked loci (e.g., due to reduced recombination or selection) (Mérot et al. 2021). While other studies investigated the effect of low recombination on genetic variation (Booker et al. 2020), here authors provide a comprehensive analysis of the effect of recombination to local PCA patterns both in empirical and simulated data sets. Findings demonstrate that low recombination (and not selection) can be the sole explanatory variable for outlier windows. The study also describes patterns of genetic variation along the genome of Eurasian blackcaps, localising at least two polymorphic inversions (Ishigohoka et al. 2022). Further investigations on the effect of model parameters (e.g., window sizes and thresholds for defining low-recombining regions), as well as the use of powerful neutrality tests are in need to clearly assess whether outlier regions experience selection and reduced recombination, and to what extent. References Booker, T. R., Yeaman, S., & Whitlock, M. C. (2020). Variation in recombination rate affects detection of outliers in genome scans under neutrality. Molecular Ecology, 29 (22), 4274–4279. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15501 Ishigohoka, J., Bascón-Cardozo, K., Bours, A., Fuß, J., Rhie, A., Mountcastle, J., Haase, B., Chow, W., Collins, J., Howe, K., Uliano-Silva, M., Fedrigo, O., Jarvis, E. D., Pérez-Tris, J., Illera, J. C., Liedvogel, M. (2022) Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structure. bioRxiv 2021.12.22.473882, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.22.473882 Li, H., & Ralph, P. (2019). Local PCA Shows How the Effect of Population Structure Differs Along the Genome. Genetics, 211 (1), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.118.301747 Mérot, C., Berdan, E. L., Cayuela, H., Djambazian, H., Ferchaud, A.-L., Laporte, M., Normandeau, E., Ragoussis, J., Wellenreuther, M., & Bernatchez, L. (2021). Locally Adaptive Inversions Modulate Genetic Variation at Different Geographic Scales in a Seaweed Fly. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 38 (9), 3953–3971. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab143 | Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structure | Jun Ishigohoka, Karen Bascón-Cardozo, Andrea Bours, Janina Fuß, Arang Rhie, Jacquelyn Mountcastle, Bettina Haase, William Chow, Joanna Collins, Kerstin Howe, Marcela Uliano-Silva, Olivier Fedrigo, Erich D. Jarvis, Javier Pérez-Tris, Juan Carlos Il... | <p>Genetic variation of the entire genome represents population structure, yet individual loci can show distinct patterns. Such deviations identified through genome scans have often been attributed to effects of selection instead of randomness. Th... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Matteo Fumagalli | 2023-10-13 11:58:47 | View | |

11 May 2023

Co-obligate symbioses have repeatedly evolved across aphids, but partner identity and nutritional contributions vary across lineagesAlejandro Manzano-Marín, Armelle Coeur d'acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, Emmanuelle Jousselin https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.28.505559Flexibility in Aphid Endosymbiosis: Dual Symbioses Have Evolved Anew at Least Six TimesRecommended by Olivier Tenaillon based on reviews by Alex C. C. Wilson and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this intriguing study (Manzano-Marín et al. 2022) by Alejandro Manzano-Marin and his colleagues, the association between aphids and their symbionts is investigated through meta-genomic analysis of new samples. These associations have been previously described as leading to fascinating genomic evolution in the symbiont (McCutcheon and Moran 2012). The bacterial genomes exhibit a significant reduction in size and the range of functions performed. They typically lose the ability to produce many metabolites or biobricks created by the host, and instead, streamline their metabolism by focusing on the amino acids that the host cannot produce. This level of co-evolution suggests a stable association between the two partners. However, the new data suggests a much more complex pattern as multiple independent acquisitions of co-symbionts are observed. Co-symbiont acquisition leads to a partition of the functions carried out on the bacterial side, with the new co-symbiont taking over some of the functions previously performed by Buchnera. In most cases, the new co-symbiont also brings the ability to produce B1 vitamin. Various facultative symbiotic taxa are recruited to be co-symbionts, with the frequency of acquisition related to the bacterial niche and lifestyle. REFERENCES Manzano-Marín, Alejandro, Armelle Coeur D’acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, and Emmanuelle Jousselin. 2023. “Co-Obligate Symbioses Have Repeatedly Evolved across Aphids, but Partner Identity and Nutritional Contributions Vary across Lineages.” bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.28.505559. McCutcheon, John P., and Nancy A. Moran. 2012. “Extreme Genome Reduction in Symbiotic Bacteria.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 10 (1): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2670. | Co-obligate symbioses have repeatedly evolved across aphids, but partner identity and nutritional contributions vary across lineages | Alejandro Manzano-Marín, Armelle Coeur d'acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, Emmanuelle Jousselin | <p style="text-align: justify;">Aphids are a large family of phloem-sap feeders. They typically rely on a single bacterial endosymbiont, <em>Buchnera aphidicola</em>, to supply them with essential nutrients lacking in their diet. This association ... |  | Genome Evolution, Other, Species interactions | Olivier Tenaillon | 2022-11-16 10:13:37 | View | |

21 Feb 2023

Wolbachia genomics reveals a potential for a nutrition-based symbiosis in blood-sucking Triatomine bugsJonathan Filée, Kenny Agésilas-Lequeux, Laurie Lacquehay, Jean Michel Bérenger, Lise Dupont, Vagner Mendonça, João Aristeu da Rosa, Myriam Harry https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.06.506778Nutritional symbioses in triatomines: who is playing?Recommended by Natacha Kremer based on reviews by Alejandro Manzano Marín and Olivier DuronNearly 8 million people are suffering from Chagas disease in the Americas. The etiological agent, Trypanosoma cruzi, is mainly transmitted by triatomine bugs, also known as kissing or vampire bugs, which suck blood and transmit the parasite through their feces. Among these triatomine species, Rhodnius prolixus is considered the main vector, and many studies have focused on characterizing its biology, physiology, ecology and evolution. Interestingly, given that Rhodnius species feed almost exclusively on blood, their diet is unbalanced, and the insects can lack nutrients and vitamins that they cannot synthetize themself, such as B-vitamins. In all insects feeding exclusively on blood, symbioses with microbes producing B-vitamins (mainly biotin, riboflavin and folate) have been widely described (see review in Duron and Gottlieb 2020) and are critical for insect development and reproduction. These co-evolved relationships between blood feeders and nutritional symbionts could now be considered to develop new control methods, by targeting the ‘Achille’s heel’ of the symbiotic association (i.e., transfer of nutrient and / or control of nutritional symbiont density). But for this, it is necessary to better characterize the relationships between triatomines and their symbionts. R. prolixus is known to be associated with several symbionts. The extracellular gut symbiont Rhodococcus rhodnii, which reaches high bacterial densities and is almost fixed in R. prolixus populations, appears to be a nutritional symbiont under many blood sources. This symbiont can provide B-vitamins such as biotin (B7), niacin (B3), thiamin (B1), pyridoxin (B6) or riboflavin (B2) and can play an important role in the development and the reproduction of R. prolixus (Pachebat et al. (2013) and see review in Salcedo-Porras et al. (2020)). This symbiont is orally acquired through egg smearing, ensuring the fidelity of transmission of the symbiont from mother to offspring. However, as recently highlighted by Tobias et al. (2020) and Gilliland et al. (2022), other gut microbes could also participate to the provision of B-vitamins, and R. rhodnii could additionally provide metabolites (other than B-vitamins) increasing bug fitness. In the study from Filée et al., the authors focused on Wolbachia, an intracellular, maternally inherited bacterium, known to be a nutritional symbiont in other blood-sucking insects such as bedbugs (Nikoh et al. 2014), and its potential role in vitamin provision in triatomine bugs. After screening 17 different triatomine species from the 3 phylogenetic groups prolixus, pallescens and pictipes, they first show that Wolbachia symbionts are widely distributed in the different Rhodnius species. Contrary to R. rhodnii that were detected in all samples, Wolbachia prevalence was patchy and rarely fixed. The authors then sequenced, assembled, and compared 13 Wolbachia genomes from the infected Rhodnius species. They showed that all Wolbachia are phylogenetically positioned in the supergroup F that contains wCle (the Wolbachia from bedbugs). In addition, 8 Wolbachia strains (out of 12) encode a biotin operon under strong purifying selection, suggesting the preservation of the biological function and the metabolic potential of Wolbachia to supplement biotin in their Rhodnius host. From the study of insect genomes, the authors also evidenced several horizontal transfers of genes from Wolbachia to Rhodnius genomes, which suggests a complex evolutionary interplay between vampire bugs and their intracellular symbiont. This nice piece of work thus provides valuable information to the fields of multiple partners / nutritional symbioses and Wolbachia research. Dual symbioses described in insects feeding on unbalanced diets generally highlight a certain complementarity between symbionts that ensure the whole nutritional complementation. The study presented by Filée et al. leads rather to consider the impact of multiple symbionts with different lifestyles and transmission modes in the provision of a specific nutritional benefit (here, biotin). Because of the low prevalence of Wolbachia in certain species, a “ménage à trois” scenario would rather be replaced by an “open couple”, where the host relationship with new symbiotic partners (more or less stable at the evolutionary timescale) could provide benefits in certain ecological situations. The results also support the potential for Wolbachia to evolve rapidly along a continuum between parasitism and mutualism, by acquiring operons encoding critical pathways of vitamin biosynthesis. References Duron O. and Gottlieb Y. (2020) Convergence of Nutritional Symbioses in Obligate Blood Feeders. Trends in Parasitology 36(10):816-825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2020.07.007 Filée J., Agésilas-Lequeux K., Lacquehay L., Bérenger J.-M., Dupont L., Mendonça V., Aristeu da Rosa J. and Harry M. (2023) Wolbachia genomics reveals a potential for a nutrition-based symbiosis in blood-sucking Triatomine bugs. bioRxiv, 2022.09.06.506778, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.06.506778 Gilliland C.A. et al. (2022) Using axenic and gnotobiotic insects to examine the role of different microbes on the development and reproduction of the kissing bug Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Molecular Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16800 Nikoh et al. (2014) Evolutionary origin of insect–Wolbachia nutritional mutualism. PNAS. 111(28):10257-10262. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1409284111 Pachebat, J.A. et al. (2013). Draft genome sequence of Rhodococcus rhodnii strain LMG5362, a symbiont of Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae), the principle vector of Trypanosoma cruzi. Genome Announc. 1(3):e00329-13. https://doi.org/10.1128/genomea.00329-13 Salcedo-Porras N., et al. (2020). The role of bacterial symbionts in Triatomines: an evolutionary perspective. Microorganisms. 8:1438. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fmicroorganisms8091438 Tobias N.J., Eberhard F.E., Guarneri A.A. (2020) Enzymatic biosynthesis of B-complex vitamins is supplied by diverse microbiota in the Rhodnius prolixus anterior midgut following Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 3395-3401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2020.10.031 | Wolbachia genomics reveals a potential for a nutrition-based symbiosis in blood-sucking Triatomine bugs | Jonathan Filée, Kenny Agésilas-Lequeux, Laurie Lacquehay, Jean Michel Bérenger, Lise Dupont, Vagner Mendonça, João Aristeu da Rosa, Myriam Harry | <p>The nutritional symbiosis promoted by bacteria is a key determinant for adaptation and evolution of many insect lineages. A complex form of nutritional mutualism that arose in blood-sucking insects critically depends on diverse bacterial symbio... |  | Genome Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Species interactions | Natacha Kremer | Alejandro Manzano Marín | 2022-09-13 17:36:46 | View |

18 Jun 2020

Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in betweenFanny Pouyet and Kimberly J. Gilbert http://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11490Molecular evolution through the joint lens of genomic and population processes.Recommended by Guillaume Achaz based on reviews by Benoit Nabholz and 1 anonymous reviewerIn their perspective article, F Pouyet and KJ Gilbert (2020), propose an interesting overview of all the processes that sculpt patterns of molecular evolution. This well documented article covers most (if not all) important facets of the recurrent debate that has marked the history of molecular evolution: the relative importance of natural selection and neutral processes (i.e. genetic drift). I particularly enjoyed reading this review, that instead of taking a clear position on the debate, catalogs patiently every pieces of information that can help understand how patterns we observed at the genome level, can be understood from a selectionnist point of view, from a neutralist one, and, to quote their title, from "everything in between". The review covers the classical objects of interest in population genetics (genetic drift, selection, demography and structure) but also describes several genomic processes (meiotic drive, linked selection, gene conversion and mutation processes) that obscure the interpretation of these population processes. The interplay between all these processes is very complex (to say the least) and have resulted in many cases in profound confusions while analyzing data. It is always very hard to fully acknowledge our ignorance and we have many times payed the price of model misspecifications. This review has the grand merit to improve our awareness in many directions. Being able to cover so many aspects of a wide topic, while expressing them simply and clearly, connecting concepts and observations from distant fields, is an amazing "tour de force". I believe this article constitutes an excellent up-to-date introduction to the questions and problems at stake in the field of molecular evolution and will certainly also help established researchers by providing them a stimulating overview supported with many relevant references. References [1] Pouyet F, Gilbert KJ (2020) Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between. arXiv:1909.11490 [q-bio]. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. url:https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11490 | Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between | Fanny Pouyet and Kimberly J. Gilbert | <p>A major goal of molecular evolutionary biology is to identify loci or regions of the genome under selection versus those evolving in a neutral manner. Correct identification allows accurate inference of the evolutionary process and thus compreh... |  | Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Guillaume Achaz | 2019-09-26 10:58:10 | View | |

01 Jul 2022

Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fuscaKamil S. Jaron, Christina N. Hodson, Jacintha Ellers, Stuart JE Baird, Laura Ross https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.12.468426Pressing NGS data through the mill of Kmer spectra and allelic coverage ratios in order to scan reproductive modes in non-model speciesRecommended by Nicolas Bierne based on reviews by Paul Simion and 2 anonymous reviewersThe genomic revolution has given us access to inexpensive genetic data for any species. Simultaneously we have lost the ability to easily identify chimerism in samples or some unusual deviations from standard Mendelian genetics. Methods have been developed to identify sex chromosomes, characterise the ploidy, or understand the exact form of parthenogenesis from genomic data. However, we rarely consider that the tissues we extract DNA from could be a mixture of cells with different genotypes or karyotypes. This can nonetheless happen for a variety of (fascinating) reasons such as somatic chromosome elimination, transmissible cancer, or parental genome elimination. Without a dedicated analysis, it is very easy to miss it. In this preprint, Jaron et al. (2022) used an ingenious analysis of whole individual NGS data to test the hypothesis of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca. The authors suspected that a high fraction of the whole body of males is made of sperm in this species and if this species undergoes paternal genome elimination, we would expect that sperm would only contain maternally inherited chromosomes. Given the reference genome was highly fragmented, they developed a two-tissue model to analyse Kmer spectra and obtained confirmation that around one-third of the tissue was sperm in males. This allowed them to test whether coverage patterns were consistent with the species exhibiting paternal genome elimination. They combined their estimation of the fraction of haploid tissue with allele coverages in autosomes and the X chromosome to obtain support for a bias toward one parental allele, suggesting that all sperm carries the same parental haplotype. It could be the maternal or the paternal alleles, but paternal genome elimination is most compatible with the known biology of Arthropods. SNP calling was used to confirm conclusions based on the analysis of the raw pileups. I found this study to be a good example of how a clever analysis of Kmer spectra and allele coverages can provide information about unusual modes of reproduction in a species, even though it does not have a well-assembled genome yet. As advocated by the authors, routine inspection of Kmer spectra and allelic read-count distributions should be included in the best practice of NGS data analysis. They provide the method to identify paternal genome elimination but also the way to develop similar methods to detect another kind of genetic chimerism in the avalanche of sequence data produced nowadays. References Jaron KS, Hodson CN, Ellers J, Baird SJ, Ross L (2022) Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca. bioRxiv, 2021.11.12.468426, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.12.468426 | Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca | Kamil S. Jaron, Christina N. Hodson, Jacintha Ellers, Stuart JE Baird, Laura Ross | <p style="text-align: justify;">Paternal genome elimination (PGE) - a type of reproduction in which males inherit but fail to pass on their father’s genome - evolved independently in six to eight arthropod clades. Thousands of species, including s... | Genome Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Nicolas Bierne | 2021-11-18 00:09:43 | View | ||

07 Sep 2018

Parallel pattern of differentiation at a genomic island shared between clinal and mosaic hybrid zones in a complex of cryptic seahorse lineagesFlorentine Riquet, Cathy Liautard-Haag, Lucy Woodall, Carmen Bouza, Patrick Louisy, Bojan Hamer, Francisco Otero-Ferrer, Philippe Aublanc, Vickie Béduneau, Olivier Briard, Tahani El Ayari, Sandra Hochscheid, Khalid Belkhir, Sophie Arnaud-Haond, Pierre-Alexandre Gagnaire, Nicolas Bierne https://doi.org/10.1101/161786Genomic parallelism in adaptation to orthogonal environments in sea horsesRecommended by Yaniv Brandvain based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersStudies in speciation genomics have revealed that gene flow is quite common, and that despite this, species can maintain their distinct environmental adaptations. Although researchers are still elucidating the genomic mechanisms by which species maintain their adaptations in the face of gene flow, this often appears to involve few diverged genomic regions in otherwise largely undifferentiated genomes. In this preprint [1], Riquet and colleagues investigate the genetic structuring and patterns of parallel evolution in the long-snouted seahorse. References [1] Riquet, F., Liautard-Haag, C., Woodall, L., Bouza, C., Louisy, P., Hamer, B., Otero-Ferrer, F., Aublanc, P., Béduneau, V., Briard, O., El Ayari, T., Hochscheid, S. Belkhir, K., Arnaud-Haond, S., Gagnaire, P.-A., Bierne, N. (2018). Parallel pattern of differentiation at a genomic island shared between clinal and mosaic hybrid zones in a complex of cryptic seahorse lineages. bioRxiv, 161786, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/161786 | Parallel pattern of differentiation at a genomic island shared between clinal and mosaic hybrid zones in a complex of cryptic seahorse lineages | Florentine Riquet, Cathy Liautard-Haag, Lucy Woodall, Carmen Bouza, Patrick Louisy, Bojan Hamer, Francisco Otero-Ferrer, Philippe Aublanc, Vickie Béduneau, Olivier Briard, Tahani El Ayari, Sandra Hochscheid, Khalid Belkhir, Sophie Arnaud-Haond, Pi... | <p>Diverging semi-isolated lineages either meet in narrow clinal hybrid zones, or have a mosaic distribution associated with environmental variation. Intrinsic reproductive isolation is often emphasized in the former and local adaptation in the la... |  | Hybridization / Introgression, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Yaniv Brandvain | Kathleen Lotterhos, Sarah Fitzpatrick | 2017-07-11 13:12:40 | View |

08 Jan 2024

Genomic relationships among diploid and polyploid species of the genus Ludwigia L. section Jussiaea using a combination of molecular cytogenetic, morphological, and crossing investigationsD. Barloy, L. Portillo - Lemus, S. A. Krueger-Hadfield, V. Huteau, O. Coriton https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.02.522458Deciphering the genomic composition of tetraploid, hexaploid and decaploid Ludwigia L. species (section Jussiaea)Recommended by Malika AINOUCHE based on reviews by Alex BAUMEL and Karol MARHOLDPolyploidy, which results in the presence of more than two sets of homologous chromosomes represents a major feature of plant genomes that have undergone successive rounds of duplication followed by more or less rapid diploidization during their evolutionary history. Polyploid complexes containing diploid and derived polyploid taxa are excellent model systems for understanding the short-term consequences of whole genome duplication, and have been particularly well-explored in evolutionary ecology (Ramsey and Ramsey 2014, Rice et al. 2019). Many polyploids (especially when resulting from interspecific hybridization, i.e. allopolyploids) are successful invaders (te Beest et al. 2012) as a result of rapid genome dynamics, functional novelty, and trait evolution. The origin (parental legacy) and modes of formation of polyploids have a critical impact on the subsequent polyploid evolution. Thus, elucidation of the genomic composition of polyploids is fundamental to understanding trait evolution, and such knowledge is still lacking for many invasive species. Genus Ludwigia is characterized by a complex taxonomy, with an underexplored evolutionary history. Species from section Jussieae form a polyploid complex with diploids, tetraploids, hexaploids, and decaploids that are notorious invaders in freshwater and riparian ecosystems (Thouvenot et al.2013). Molecular phylogeny of the genus based on nuclear and chloroplast sequences (Liu et al. 2027) suggested some relationships between diploid and polyploid species, without fully resolving the question of the parentage of the polyploids. In their study, Barloy et al. (2023) have used a combination of molecular cytogenetics (Genomic In situ Hybridization), morphology and experimental crosses to elucidate the genomic compositions of the polyploid species, and show that the examined polyploids are of hybrid origin (allopolyploids). The tetraploid L. stolonifera derives from the diploids L. peploides subsp. montevidensis (AA genome) and L. helminthorhiza (BB genome). The tetraploid L. ascendens also share the BB genome combined with an undetermined different genome. The hexaploid L. grandiflora subsp. grandiflora has inherited the diploid AA genome combined with additional unidentified genomes. The decaploid L. grandiflora subsp. hexapetala has inherited the tetraploid L. stolonifera and the hexaploid L. grandiflora subsp. hexapetala genomes. As the authors point out, further work is needed, including additional related diploid (e.g. other subspecies of L. peploides) or tetraploid (L. hookeri and L. peduncularis) taxa that remain to be investigated, to address the nature of the undetermined parental genomes mentioned above. The presented work (Barloy et al. 2023) provides significant knowledge of this poorly investigated group with regard to genomic information and polyploid origin, and opens perspectives for future studies. The authors also detect additional diagnostic morphological traits of interest for in-situ discrimination of the taxa when monitoring invasive populations. References Barloy D., Portillo-Lemus L., Krueger-Hadfield S.A., Huteau V., Coriton O. (2024). Genomic relationships among diploid and polyploid species of the genus Ludwigia L. section Jussiaea using a combination of molecular cytogenetic, morphological, and crossing investigations. BioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.02.522458 te Beest M., Le Roux J.J., Richardson D.M., Brysting A.K., Suda J., Kubešová M., Pyšek P. (2012). The more the better? The role of polyploidy in facilitating plant invasions. Annals of Botany, Volume 109, Issue 1 Pages 19–45, https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcr277 Ramsey J. and Ramsey T. S. (2014). Ecological studies of polyploidy in the 100 years following its discovery Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B369 1–20 https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0352 Rice, A., Šmarda, P., Novosolov, M. et al. (2019). The global biogeography of polyploid plants. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0787-9 Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiebaut G. (2013). A success story: Water primroses, aquatic plant pests. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 23:790–803 https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2387 | Genomic relationships among diploid and polyploid species of the genus *Ludwigia* L. section *Jussiaea* using a combination of molecular cytogenetic, morphological, and crossing investigations | D. Barloy, L. Portillo - Lemus, S. A. Krueger-Hadfield, V. Huteau, O. Coriton | <p>ABSTRACTThe genus Ludwigia L. sectionJussiaeais composed of a polyploid species complex with 2x, 4x, 6x and 10x ploidy levels, suggesting possible hybrid origins. The aim of the present study is to understand the genomic relationships among dip... |  | Hybridization / Introgression, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Malika AINOUCHE | 2023-01-11 13:47:18 | View | |

16 Nov 2018

Fine-grained habitat-associated genetic connectivity in an admixed population of mussels in the small isolated Kerguelen IslandsChristelle Fraïsse, Anne Haguenauer, Karin Gerard, Alexandra Anh-Thu Weber, Nicolas Bierne, Anne Chenuil https://doi.org/10.1101/239244Introgression from related species reveals fine-scale structure in an isolated population of mussels and causes patterns of genetic-environment associationsRecommended by Marianne Elias based on reviews by Thomas Broquet and Tatiana GiraudAssessing population connectivity is central to understanding population dynamics, and is therefore of great importance in evolutionary biology and conservation biology. In the marine realm, the apparent absence of physical barriers, large population sizes and high dispersal capacities of most organisms often result in no detectable structure, thereby hindering inferences of population connectivity. In a review paper, Gagnaire et al. [1] propose several ideas to improve detection of population connectivity. Notably, using simulations they show that under certain circumstances introgression from one species into another may reveal cryptic population structure within that second species. References [1] Gagnaire, P.-A., Broquet, T., Aurelle, D., Viard, F., Souissi, A., Bonhomme, F., Arnaud-Haond, S., & Bierne, N. (2015). Using neutral, selected, and hitchhiker loci to assess connectivity of marine populations in the genomic era. Evolutionary Applications, 8, 769–786. doi: 10.1111/eva.12288 | Fine-grained habitat-associated genetic connectivity in an admixed population of mussels in the small isolated Kerguelen Islands | Christelle Fraïsse, Anne Haguenauer, Karin Gerard, Alexandra Anh-Thu Weber, Nicolas Bierne, Anne Chenuil | <p>Reticulated evolution -i.e. secondary introgression / admixture between sister taxa- is increasingly recognized as playing a key role in structuring infra-specific genetic variation and revealing cryptic genetic connectivity patterns. When admi... |  | Hybridization / Introgression, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Marianne Elias | 2017-12-28 14:16:16 | View | |

22 Feb 2023

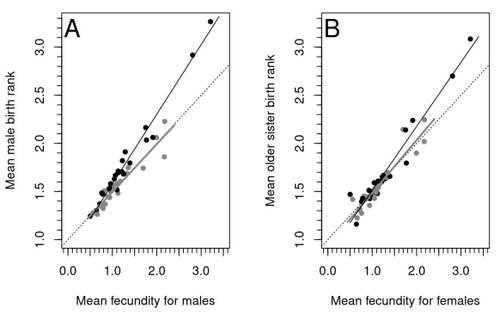

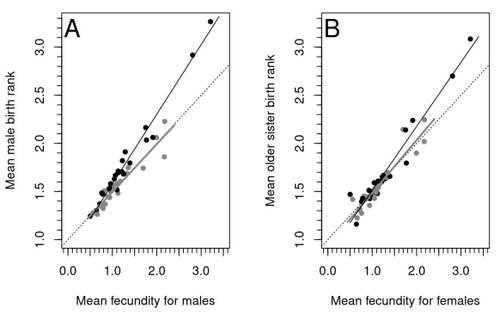

Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesisMichel Raymond, Daniel Turek, Valerie Durand, Sarah Nila, Bambang Suryobroto, Julien Vadez, Julien Barthes, Menelaos Apostolou, Pierre-André Crochet https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.22.481477Evolutionary or proximal explanations for human male homosexual mate preference?Recommended by Jacqui A. Shykoff based on reviews by Ray Blanchard and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Ray Blanchard and 1 anonymous reviewer

Natural populations do not consist of only perfectly adapted individuals. If they did, of course, there would be no fodder for evolution by natural selection. And natural selection is operating all the time, winnowing out less well adapted phenotypes through differential reproduction and survival. Demonstrations of natural selection modifying characters-state distributions to bring phenotypes closer to their optima abound in the evolution literature, with examples of short- and long-term changes in phenotype and allele frequencies. However, evolutionary biologists know that populations cannot reach their adaptive peaks. Natural selection is tracking a moving target, always with some generations of lag time. The adaptive landscape is multidimensional, so the optimal combination of multiple character states may be impossible because of constraints and trade-offs. Natural selection does not operate alone or in isolation – new mutations and migrants that were selected under other conditions will inject locally non-adaptive genetic variation and genetic drift can change allele frequencies in random directions. We understand these processes that generate and maintain less advantageous variants on a continuous gradient from an optimal phenotype in a fitness landscape. More puzzling are heritable polymorphisms with distinct morphologies, physiologies or behaviours maintained in populations despite their measurably lower reproductive success. But a complete model of evolution must also be able to accommodate these Darwinian paradoxes. Raymond et al. (2023) investigate one such Darwinian paradox: In humans, male homosexual mate preference is heritable and is associated with a large reduction in offspring production but nonetheless occurs at relatively high frequencies in most human populations. Furthermore, multiple studies have found that homosexual men come from families that are, on average, larger than those of heterosexual men and that homosexual men have, on average, higher birth rank than do heterosexual men, i.e., having more older siblings and, particularly, more older brothers. Two types of mechanisms consistent with these observations have been proposed: 1) An evolutionary mechanism of sex-antagonistic pleiotropy, whereby highly fecund mothers are more likely to produce homosexual sons, and 2) A mechanistic explanation whereby successive male pregnancies alter the uterine environment by increasing the probability of an immune reaction by the mother to her male fetus, altering development of sexually dimorphic brain structures relevant to sexual orientation. In this article, the authors explore these two mechanisms of sex-antagonistic effects (AE) and fraternal birth order effects (FBOE) and test how well they account for patterns of male homosexuality in population and family data. Clearly, these two effects are somewhat confounded because high birth ranks can only occur in large families. If, indeed, the probability of male homosexuality increases with increasing numbers of (maternal) older brothers, homosexual males will be more common in larger families. Similarly, if high female fecundity leads to a higher probability of male homosexuality via sex-antagonistic effects, homosexual males will, on average, have more older brothers. To disentangle the actions of these two effects the authors modelled the relationship between birth rank and population fecundity and investigated whether AE or FBOE modified this relationship for homosexual men. Simulation results were compared with aggregated population data from 13 countries. Family data on individuals’ sexual preference, birth rank and number of male and female siblings from France, Greece and Indonesia were analysed with generalised linear models and Bayesian approaches to test for a signal of AE or FBOE. These analyses revealed a significant older-brother effect (FBOE) explaining patterns of occurrence of homosexuality in population and family data but no significant independent sex-antagonistic effect (AE). Thus larger family sizes of homosexual men appear due to the older-brother effect, with individuals of high birth rank coming necessarily from large sibships. The simulation approach also revealed that modelling a fraternal birth order effect (FBOE), such that individuals with more older brothers are more likely to be homosexual, generates an artefactual older sister effect simply because homosexual men are overrepresented at higher birth ranks. Older-sister effects reported in the literature may, therefore, be statistical artefacts of an underlying older-brother effect. This paper is interesting for a number of reasons. It does an excellent job of explaining, identifying and dealing with estimation biases and testing for artefactual relationships generated by collinearity. It applies state-of-the art analytical/statistical tools. It breaks down two colinear effects and shows that only one really explains phenotypic variation. This is a great example of how to disentangle correlated variables that may or may not both contribute to trait variation. But most intriguingly, we are left without evidence for an evolutionary mechanism that compensates the large fitness cost associated with male homosexuality in humans. How can we explain high heritability maintained in the face of strong directional selection that should erode heritable genetic variation? The usual suspects include cryptic compensatory mechanisms yet to be discovered or flawed estimates of selection or heritability. For example, data on heritability of male homosexual mate preference in humans come from twin studies and twins share birth rank as well as alleles. Thus it is possible that heritability is over-estimated, including the environmental component associated with birth rank. If, as the authors demonstrate here, birth rank is the strongest predictor of male homosexual mate preference, selection may be acting on a non-heritable plastic component of phenotypic variation. This could explain why heritable variation is not exhausted by selection, rendering the paradox less paradoxical, but fails to provide an adaptive explanation for the maintenance of male homosexual mate preference. References Raymond M., Turek D., Durand V., Nila S., Suryobroto B., Vadez J., Barthes J., Apostolou M. and Crochet P.-A. (2023) Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesis. bioRxiv, 2022.02.22.481477, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.22.481477 | Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesis | Michel Raymond, Daniel Turek, Valerie Durand, Sarah Nila, Bambang Suryobroto, Julien Vadez, Julien Barthes, Menelaos Apostolou, Pierre-André Crochet | <p style="text-align: justify;">Male homosexual orientation remains a Darwinian paradox, as there is no consensus on its evolutionary (ultimate) determinants. One intriguing feature of homosexual men is their higher male birth rank compared to het... |  | Life History, Other, Phenotypic Plasticity, Reproduction and Sex | Jacqui A. Shykoff | 2022-03-03 11:28:44 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer