Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

19 Mar 2018

Natural selection on plasticity of thermal traits in a highly seasonal environmentLeonardo Bacigalupe, Juan Diego Gaitan-Espitia, Aura M Barria, Avia Gonzalez-Mendez, Manuel Ruiz-Aravena, Mark Trinder, Barry Sinervo https://doi.org/10.1101/191825Is thermal plasticity itself shaped by natural selection? An assessment with desert frogsRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn based on reviews by Dries Bonte, Wolf Blanckenhorn and Nadia Aubin-HorthIt is well known that climatic factors – most notably temperature, season length, insolation and humidity – shape the thermal niche of organisms on earth through the action of natural selection. But how is this achieved precisely? Much of thermal tolerance is actually mediated by phenotypic plasticity (as opposed to genetic adaptation). A prominent expectation is that environments with greater (daily and/or annual) thermal variability select for greater plasticity, i.e. better acclimation capacity. Thus, plasticity might be selected per se. A Chilean group around Leonardo Bacigalupe assessed natural selection in the wild in one marginal (and extreme) population of the four-eyed frog Pleurodema thaul (Anura: Leptodactylidae) in an isolated oasis in the Atacama Desert, permitting estimation of mortality without much potential of confounding it with migration [1]. Several thermal traits were considered: CTmax – the critical maximal temperature; CTmin – the critical minimum temperature; Tpref – preferred temperature; Q10 – thermal sensitivity of metabolism; and body mass. Animals were captured in the wild and subsequently assessed for thermal traits in the laboratory at two acclimation temperatures (10° & 20°C), defining the plasticity in all traits as the difference between the traits at the two acclimation temperatures. Thereafter the animals were released again in their natural habitat and their survival was monitored over the subsequent 1.5 years, covering two breeding seasons, to estimate viability selection in the wild. The authors found and conclude that, aside from larger body size increasing survival (an unsurprising result), plasticity does not seem to be systematically selected directly, while some of the individual traits show weak signs of selection. Despite limited sample size (ca. 80 frogs) investigated in only one marginal but very seasonal population, this study is interesting because selection on plasticity in physiological thermal traits, as opposed to selection on the thermal traits themselves, is rarely investigated. The study thus also addressed the old but important question of whether plasticity (i.e. CTmax-CTmin) is a trait by itself or an epiphenomenon defined by the actual traits (CTmax and CTmin) [2-5]. Given negative results, the main question could not be ultimately solved here, so more similar studies should be performed. References [1] Bacigalupe LD, Gaitan-Espitia, JD, Barria AM, Gonzalez-Mendez A, Ruiz-Aravena M, Trinder M & Sinervo B. 2018. Natural selection on plasticity of thermal traits in a highly seasonal environment. bioRxiv 191825, ver. 5 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/191825 | Natural selection on plasticity of thermal traits in a highly seasonal environment | Leonardo Bacigalupe, Juan Diego Gaitan-Espitia, Aura M Barria, Avia Gonzalez-Mendez, Manuel Ruiz-Aravena, Mark Trinder, Barry Sinervo | <p>For ectothermic species with broad geographical distributions, latitudinal/altitudinal variation in environmental temperatures (averages and extremes) are expected to shape the evolution of physiological tolerances and the acclimation capacity ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2017-09-22 23:17:40 | View | |

04 Aug 2023

Sensitive windows for within- and trans-generational plasticity of anti-predator defencesJuliette Tariel-Adam; Émilien Luquet; Sandrine Plénet https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/mr8huSensitive windows for phenotypic plasticity within and across generations; where empirical results do not meet the theory but open a world of possibilitiesRecommended by Benoit Pujol based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker, Timothée Bonnet and Willem FrankenhuisIt is easy to define phenotypic plasticity as a mechanism by which traits change in response to a modification of the environment. Many complex mechanisms are nevertheless involved with plastic responses, their strength, and stability (e.g., reliability of cues, type of exposure, genetic expression, epigenetics). It is rather intuitive to think that environmental cues perceived at different stages of development will logically drive different phenotypic responses (Fawcett and Frankenhuis 2015). However, it has proven challenging to try and explain, or model how and why different effects are caused by similar cues experienced at different developmental or life stages (Walasek et al. 2022). The impact of these ‘sensitive windows’ on the stability of plastic responses within or across generations remains unclear. In their paper entitled “Sensitive windows for within- and trans-generational plasticity of anti-predator defences”, Tariel-Adam (2023) address this question. In this paper, Tariel et al. acknowledge the current state of the art, i.e., that some traits influenced by the environment at early life stages become fixed later in life (Snell-Rood et al. 2015) and that sensitive windows are therefore more likely to be observed during early stages of development. Constructive exchanges with the reviewers illustrated that Tariel et al. presented a clear picture of the knowledge on sensitive windows from a conceptual and a mechanistic perspective, thereby providing their study with a strong and elegant rationale. Tariel et al. outlined that little is known about the significance of this scenario when it comes to transgenerational plasticity. Theory predicts that exposure late in the life of parents should be more likely to drive transgenerational plasticity because the cue perceived by parents is more likely to be reliable if time between parental exposure and offspring expression is short (McNamara et al. 2016). I would argue that although sensible, this scenario is likely oversimplifying the complexity of evolutionary, ecological, and inheritance mechanisms at play (Danchin et al. 2018). Tariel-Adam et al. (2023) point out in their paper how the absence of experimental results limits our understanding of the evolutionary and adaptive significance of transgenerational plasticity and decided to address this broad question. Tariel-Adam et al. (2023) used the context of predator-prey interactions, which is a powerful framework to evaluate the temporality of predator cues and prey responses within and across generations (Sentis et al. 2018). They conducted a very elegant experiment whereby two generations of freshwater snails Physa acuta were exposed to crayfish predator cues at different developmental windows. They triggered the within-generation phenotypic plastic response of inducible defences (e.g., shell thickness) and identified sensitive windows as to evaluate their role in within-generation phenotypic plasticity versus transgenerational plasticity. They used different linear models, which lead to constructive exchanges with reviewers, and between reviewers, well trained on these approaches, in particular on effect sizes, that improved the paper by pushing the discussion all the way towards a consensus. Tariel-Adam et al. (2023) results showed that the phenotypic plastic response of different traits was associated with different sensitive windows. Although early-life development was confirmed to be a sensitive window, it was far from being the only developmental stage driving within-generation plastic responses of defence traits. This finding contributes to change our views on plasticity because where theoretical models predict early- and late-life sensitive windows, empirical results gathered here present a more continuous opportunity for sensitive windows over the lifetime of freshwater snails. This is likely because multifactorial mechanisms drive the reliability and adaptive significance of predator cues. To me, this paper most original contribution lies probably in the empirical investigation of sensitive windows underlying transgenerational plasticity. Their finding implies mechanistic ties between sensitive windows driving within-generation and transgenerational plasticity for some traits, but they also shed light on the possible independence of these processes. Although one may be disheartened by these findings illustrating the ability of nature to combine complex mechanisms in order to produce somewhat unpredictable scenarios, one can only find that this unlimited range of phenotypic plasticity scenarios is a wonder to investigate because much remains to be understood. As mentioned in the conclusion of the paper, the opportunity for sensitive windows to drive such a range of plastic responses may also be an opportunity for organisms to adapt to a wide range of environmental demands. References Danchin E, A Pocheville, O Rey, B Pujol, and S Blanchet (2019). Epigenetically facilitated mutational assimilation: epigenetics as a hub within the inclusive evolutionary synthesis. Biological Reviews, 94: 259-282. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12453 Fawcett TW, and WE Frankenhuis (2015). Adaptive Explanations for Sensitive Windows in Development. Frontiers in Zoology 12, S3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-9994-12-S1-S3 McNamara JM, SRX Dall, P Hammerstein, and O Leimar (2016). Detection vs. Selection: Integration of Genetic, Epigenetic and Environmental Cues in Fluctuating Environments. Ecology Letters 19, 1267–1276. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12663 Sentis A, R Bertram, N Dardenne, et al. (2018). Evolution without standing genetic variation: change in transgenerational plastic response under persistent predation pressure. Heredity 121, 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-018-0108-8 Snell-Rood EC, EM Swanson, and RL Young (2015). Life History as a Constraint on Plasticity: Developmental Timing Is Correlated with Phenotypic Variation in Birds. Heredity 115, 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2015.47 Tariel-Adam J, E Luquet, and S Plénet (2023). Sensitive windows for within- and trans-generational plasticity of anti-predator defences. OSF preprints, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/mr8hu Walasek N, WE Frankenhuis, and K Panchanathan (2022). An Evolutionary Model of Sensitive Periods When the Reliability of Cues Varies across Ontogeny. Behavioral Ecology 33, 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arab113 | Sensitive windows for within- and trans-generational plasticity of anti-predator defences | Juliette Tariel-Adam; Émilien Luquet; Sandrine Plénet | <p>Transgenerational plasticity could be an important mechanism for adaptation to variable environments in addition to within-generational plasticity. But its potential for adaptation may be restricted to specific developmental windows that are hi... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Benoit Pujol | 2022-11-14 08:08:27 | View | |

21 Nov 2019

Environmental specificity in Drosophila-bacteria symbiosis affects host developmental plasticityRobin Guilhot, Antoine Rombaut, Anne Xuéreb, Kate Howell, Simon Fellous https://doi.org/10.1101/717702Nutrition-dependent effects of gut bacteria on growth plasticity in Drosophila melanogasterRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewerIt is well known that the rearing environment has strong effects on life history and fitness traits of organisms. Microbes are part of every environment and as such likely contribute to such environmental effects. Gut bacteria are a special type of microbe that most animals harbor, and as such they are part of most animals’ environment. Such microbial symbionts therefore likely contribute to local adaptation [1]. The main question underlying the laboratory study by Guilhot et al. [2] was: How much do particular gut bacteria affect the organismal phenotype, in terms of life history and larval foraging traits, of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, a common laboratory model species in biology? References [1] Kawecki, T. J. and Ebert, D. (2004) Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecology Letters 7: 1225-1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00684.x | Environmental specificity in Drosophila-bacteria symbiosis affects host developmental plasticity | Robin Guilhot, Antoine Rombaut, Anne Xuéreb, Kate Howell, Simon Fellous | <p>Environmentally acquired microbial symbionts could contribute to host adaptation to local conditions like vertically transmitted symbionts do. This scenario necessitates symbionts to have different effects in different environments. We investig... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity, Species interactions | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2019-02-13 15:22:23 | View | |

04 Mar 2024

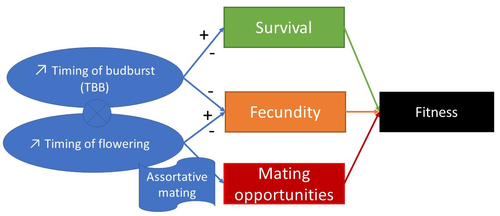

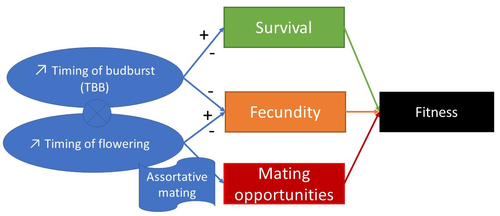

Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.).Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Aurore Bontemps, Julie Gauzere, Etienne Klein https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538521Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.)Recommended by Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Starting with the seminar paper by Lande & Arnold (1983), several studies have addressed phenotypic selection in natural populations of a wide variety of organisms, with a recent renewed interest in forest trees (e.g., Oddou-Muratorio et al. 2018; Alexandre et al. 2020; Westergren et al. 2023). Because of their long generation times, long-lived organisms such as forest trees may suffer the most from maladaptation due to climate change, and whether they will be able to adapt to new environmental conditions in just one or a few generations is hotly debated. In this study, Oddou-Muratorio and colleagues (2024) extend the current framework to add two additional selection components that may alter patterns of fecundity selection and the estimation of standard selection gradients, namely sexual selection (evaluated as differences in flowering phenology conducting to assortative mating) and growth (viability) selection. Notably, the study is conducted in two contrasted environments (low vs high altitude populations) providing information on how the environment may modulate selection patterns in spring phenology. Spring phenology is a key adaptive trait that has been shown to be already affected by climate change in forest trees (Alberto et al. 2013). While fecundity selection for early phenology has been extensively reported before (see Munguía-Rosas et al. 2011), the authors found that this kind of selection can be strongly modulated by sexual selection, depending on the environment. Moreover, they found a significant correlation between early phenology and seedling growth in a common garden, highlighting the importance of this trait for early survival in European beech. As a conclusion, this original research puts in evidence the need for more integrative approaches for the study of natural selection in the field, as well as the importance of testing multiple environments and the relevance of common gardens to further evaluate phenotypic changes due to real-time selection. PS: The recommender and the first author of the preprint have shared authorship in a recent paper in a similar topic (Westergren et al. 2023). Nevertheless, the recommender has not contributed in any way or was aware of the content of the current preprint before acting as recommender, and steps have been taken for a fair and unpartial evaluation. References Alberto, F. J., Aitken, S. N., Alía, R., González‐Martínez, S. C., Hänninen, H., Kremer, A., Lefèvre, F., Lenormand, T., Yeaman, S., Whetten, R., & Savolainen, O. (2013). Potential for evolutionary responses to climate change - evidence from tree populations. Global Change Biology, 19(6), 1645‑1661. Oddou-Muratorio S, Bontemps A, Gauzere J, Klein E (2024) Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). bioRxiv, 2023.04.27.538521, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538521 Oddou-Muratorio, S., Gauzere, J., Bontemps, A., Rey, J.-F., & Klein, E. K. (2018). Tree, sex and size: Ecological determinants of male vs. female fecundity in three Fagus sylvatica stands. Molecular Ecology, 27(15), 3131‑3145. | Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (*Fagus sylvatica* L.). | Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Aurore Bontemps, Julie Gauzere, Etienne Klein | <p>Background: Plant phenological traits such as the timing of budburst or flowering can evolve on ecological timescales through response to fecundity and viability selection. However, interference with sexual selection may arise from assortative ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez | 2023-05-02 11:57:23 | View | |

14 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

High Rates of Species Accumulation in Animals with Bioluminescent Courtship DisplaysEllis EA, Oakley TH 10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.043Bioluminescent sexually selected traits as an engine for biodiversity across animal speciesRecommended by Astrid Groot and Carole SmadjaIn evolutionary biology, sexual selection is hypothesized to increase speciation rates in animals, as theory predicts that sexual selection will contribute to phenotypic diversification and affect rates of species accumulation at macro-evolutionary time scales. However, testing this hypothesis and gathering convincing evidence have proven difficult. Although some studies have shown a strong correlation between proxies of sexual selection and species diversity (mostly in birds), this relationship relies on some assumptions on the link between these proxies and the strength of sexual selection and is not detected in some other taxa, making taxonomically widespread conclusions impossible. In a recent study published in Current Biology [1], Ellis and Oakley provide strong evidence that bioluminescent sexual displays have driven high species richness in taxonomically diverse animal lineages, providing a crucial link between sexual selection and speciation. Ellis and Oakley [1] explored the scientific literature for well-resolved evolutionary trees with branches containing bioluminescent lineages and identified lineages that use light for courtship or camouflage in a wide range of marine and terrestrial taxa including insects, crustaceans, cephalopods, segmented worms, and fishes. The researchers counted the number of species in each bioluminescent clade and found that all groups with light-courtship displays had more species and faster rates of species accumulation than their non-luminous most closely related sister lineages or ancestors. In contrast, those groups that used bioluminescence for predator avoidance had a lower than expected rate of species richness on average. Nicely encompassing a diversity of taxa and neatly controlling for the rate of species accumulation of the encompassing clade, the results of Ellis and Oakley are clear-cut and provide the most comprehensive evidence to date for the hypothesis that sexual displays can act as drivers of speciation. One question this study incites is what is happening in terms of sexual selection in species displaying defensive bioluminescence or no bioluminescence at all: do those lineages use no mating signals at all or other mating signals that are less apparent, and will those experience lower levels of sexual selection than bioluminescent mating signals, i.e. consistent with Ellis and Oakley results? It would also be interesting to investigate the diversification rates in animal species using other modalities, such as chemical, acoustic or any other type of signals used by males, females or both sexes, to determine what types of sexual signals may be more generally drivers of speciation. References [1] Ellis EA, Oakley TH. 2016. High Rates of Species Accumulation in Animals with Bioluminescent Courtship Displays. Current Biology 26:1916–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.043 [2] Davis MP, Holcroft NI, Wiley EO, Sparks JS, Smith WL. 2014. Species-specific bioluminescence facilitates speciation in the deep sea. Marine Biology 161:11391148. doi: 10.1007/s00227-014-2406-x [3] Davis MP, Sparks JS, Smith WL. 2016. Repeated and Widespread Evolution of Bioluminescence in Marine Fishes. PLoS One 11:e0155154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155154 [4] Claes JM, Nilsson D-E, Mallefet J, Straube N. 2015. The presence of lateral photophores correlates with increased speciation in deep-sea bioluminescent sharks. Royal Society Open Science 2:150219. doi: 10.1098/rsos.150219 | High Rates of Species Accumulation in Animals with Bioluminescent Courtship Displays | Ellis EA, Oakley TH | One of the great mysteries of evolutionary biology is why closely related lineages accumulate species at different rates. Theory predicts that populations undergoing strong sexual selection will more quickly differentiate because of increased pote... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Sexual Selection, Speciation | Astrid Groot | 2016-12-14 19:01:59 | View | |

31 Mar 2017

POSTPRINT

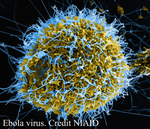

Human adaptation of Ebola virus during the West African outbreakUrbanowicz, R.A., McClure, C.P., Sakuntabhai, A., Sall, A.A., Kobinger, G., Müller, M.A., Holmes, E.C., Rey, F.A., Simon-Loriere, E., and Ball, J.K. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.013Ebola evolution during the 2013-2016 outbreakRecommended by Sylvain Gandon and Sébastien LionThe Ebola virus (EBOV) epidemic that started in December 2013 resulted in around 28,000 cases and more than 11,000 deaths. Since the emergence of the disease in Zaire in 1976 the virus had produced a number of outbreaks in Africa but until 2013 the reported numbers of human cases had never risen above 500. Could this exceptional epidemic size be due to the spread of a human-adapted form of the virus? The large mutation rate of the virus [1-2] may indeed introduce massive amounts of genetic variation upon which selection may act. Several earlier studies based on the accumulation of genome sequences sampled during the epidemic led to contrasting conclusions. A few studies discussed evidence of positive selection on the glycoprotein that may be linked to phenotypic variations on infectivity and/or immune evasion [3-4]. But the heterogeneity in the transmission of some lineages could also be due to environmental heterogeneity and/or stochasticity. Most studies could not rule out the null hypothesis of the absence of positive selection and human adaptation [1-2 and 5]. In a recent experimental study, Urbanowicz et al. [6] chose a different method to tackle this question. A phylogenetic analysis of genome sequences from viruses sampled in West Africa revealed the existence of two main lineages (one with a narrow geographic distribution in Guinea, and the other with a wider geographic distribution) distinguished by a single amino acid substitution in the glycoprotein of the virus (A82V), and of several sub-lineages characterised by additional substitutions. The authors used this phylogenetic data to generate a panel of mutant pseudoviruses and to test their ability to infect human and fruit bat cells. These experiments revealed that specific amino acid substitutions led to higher infectivity of human cells, including A82V. This increased infectivity on human cells was associated with a decreased infectivity in fruit bat cell cultures. Since fruit bats are likely to be the reservoir of the virus, this paper indicates that human adaptation may have led to a specialization of the virus to a new host. An accompanying paper in the same issue of Cell by Diehl et al. [7] reports results that confirm the trend identified by Urbanowicz et al. [6] and further indicate that the increased infectivity of A82V is specific for primate cells. Diehl et al. [7] also report some evidence for higher virulence of A82V in humans. In other words, the evolution of the virus may have led to higher abilities to infect and to kill its novel host. This work thus confirms the adaptive potential of RNA virus and the ability of Ebola to specialize to a novel host. In this context, the availability of an effective vaccine against the disease is particularly welcome [8]. The study of Urbanowicz et al. [6] is also remarkable because it illustrates the need of experimental approaches for the study of phenotypic variation when inference methods based on phylodynamics fail to extract a clear biological message. The analysis of genomic evolution is still in its infancy and there is a need for new theoretical developments to help detect more rapidly candidate mutations involved in adaptations to new environmental conditions. References [1] Gire, S.K., Goba, A., Andersen, K.G., Sealfon, R.S.G., Park, D.J., Kanneh, L., Jalloh, S., Momoh, M., Fullah, M., Dudas, G., et al. (2014). Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the 2014 outbreak. Science 345, 1369–1372. doi: 10.1126/science.1259657 | Human adaptation of Ebola virus during the West African outbreak | Urbanowicz, R.A., McClure, C.P., Sakuntabhai, A., Sall, A.A., Kobinger, G., Müller, M.A., Holmes, E.C., Rey, F.A., Simon-Loriere, E., and Ball, J.K. | The 2013–2016 outbreak of Ebola virus (EBOV) in West Africa was the largest recorded. It began following the cross-species transmission of EBOV from an animal reservoir, most likely bats, into humans, with phylogenetic analysis revealing the co-ci... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Species interactions | Sylvain Gandon | 2017-03-31 14:20:38 | View | |

03 Apr 2017

Things softly attained are long retained: Dissecting the Impacts of Selection Regimes on Polymorphism Maintenance in Experimental Spatially Heterogeneous EnvironmentsRomain Gallet, Rémy Froissart, Virginie Ravigné https://doi.org/10.1101/100743Experimental test of the conditions of maintenance of polymorphism under hard and soft selectionRecommended by Stephanie Bedhomme based on reviews by Joachim Hermisson and 2 anonymous reviewers

Theoretical work, initiated by Levene (1953) [1] and Dempster (1955) [2], suggests that within a given environment, the way populations are regulated and contribute to the next generation is a key factor for the maintenance of local adaptation polymorphism. In this theoretical context, hard selection describes the situation where the genetic composition of each population affects its contribution to the next generation whereas soft selection describes the case where the contribution of each population is fixed, whatever its genetic composition. Soft selection is able to maintain polymorphism, whereas hard selection invariably leads to the fixation of one of the alleles. Although the specific conditions (e.g. of migration between populations or drift level) in which this prediction holds have been studied in details by theoreticians, experimental tests have mainly failed, usually leading to the conclusion that the allele frequency dynamics was driven by other mechanisms in the experimental systems and conditions used. Gallet, Froissart and Ravigné [3] have set up a bacterial experimental system which allowed them to convincingly demonstrate that soft selection generates the conditions for polymorphism maintenance when hard selection does not, everything else being equal. The key ingredients of their experimental system are (1) the possibility to accurately produce hard and soft selection regimes when daily transferring the populations and (2) the ability to establish artificial well-characterized reproducible trade-offs. To do so, they used two genotypes resisting each one to one antibiotic and combined, across habitats, low antibiotic doses and difference in medium productivity. The experimental approach contains two complementary parts: the first one is looking at changes in the frequencies of two genotypes, initially introduced at around 50% each, over a small number of generations (ca 40) in different environments and selection regimes (soft/hard) and the second one is convincingly showing polymorphism protection by establishing that in soft selection regimes, the lowest fitness genotype is not eliminated even when introduced at low frequency. In this manuscript, a key point is the dialog between theoretical and experimental approaches. The experiments have been thought and designed to be as close as possible to the situations analysed in theoretical work. For example, the experimental polymorphism protection test (experiment 2) closely matches the equivalent analysis classically performed in theoretical approaches. This close fit between theory and experiment is clearly a strength of this study. This said, the experimental system allowing them to realise this close match also has some limitations. For example, changes in allele frequencies could only be monitored over a quite low number of generations because a longer time-scale would have allowed the contribution of de novo mutations and the likely emergence of a generalist genotype resisting to both antibiotics used to generate the local adaptation trade-offs. These limitations, as well as the actual significance of the experimental tests, are discussed in deep details in the manuscript. References [1] Levene H. 1953. Genetic equilibrium when more than one niche is available. American Naturalist 87: 331–333. doi: 10.1086/281792 [2] Dempster ER. 1955. Maintenance of genetic heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 20: 25–32. doi: 10.1101/SQB.1955.020.01.005 [3] Gallet R, Froissart R, Ravigné V. 2017. Things softly attained are long retained: dissecting the impacts of selection regimes on polymorphism maintenance in experimental spatially heterogeneous environments. bioRxiv 100743; doi: 10.1101/100743 | Things softly attained are long retained: Dissecting the Impacts of Selection Regimes on Polymorphism Maintenance in Experimental Spatially Heterogeneous Environments | Romain Gallet, Rémy Froissart, Virginie Ravigné | <p>Predicting and managing contemporary adaption requires a proper understanding of the determinants of genetic variation. Spatial heterogeneity of the environment may stably maintain polymorphism when habitat contribution to the next generation c... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory | Stephanie Bedhomme | 2017-01-17 11:06:21 | View | |

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

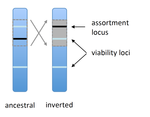

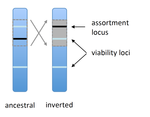

Prezygotic isolation, mating preferences, and the evolution of chromosomal inversionsDagilis AJ, Kirkpatrick M 10.1111/evo.12954The spread of chromosomal inversions as a mechanism for reinforcementRecommended by Denis Roze and Thomas Broquet

Several examples of chromosomal inversions carrying genes affecting mate choice have been reported from various organisms. Furthermore, inversions are also frequently involved in genetic isolation between populations or species. Past work has shown that inversions can spread when they capture not only some loci involved in mate choice but also loci involved in incompatibilities between hybridizing populations [1]. In this new paper [2], the authors derive analytical approximations for the selection coefficient associated with an inversion suppressing recombination between a locus involved in mate choice and one (or several) locus involved in Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities. Two mechanisms for mate choice are considered: assortative mating based on the allele present at a single locus, or a trait-preference model where one locus codes for the trait and another for the preference. The results show that such an inversion is generally favoured, the selective advantage associated with the inversion being strongest when hybridization is sufficiently frequent. Assuming pairwise epistatic interactions between loci involved in incompatibilities, selection for the inversion increases approximately linearly with the number of such loci captured by the inversion. This paper is a good read for several reasons. First, it presents the problem clearly (e.g. the introduction provides a clear and concise presentation of the issue and past work) and its crystal-clear writing facilitates the reader's understanding of theoretical approaches and results. Second, the analysis is competently done and adds to previous work by showing that very general conditions are expected to be favourable to the spread of the type of inversion considered here. And third, it provides food for thought about the role of inversions in the origin or the reinforcement of divergence between nascent species. One result of this work is that an inversion linked to pre-zygotic isolation "is favoured so long as there is viability selection against recombinant genotypes", suggesting that genetic incompatibilities must have evolved first and that inversions capturing mating preference loci may then enhance pre-existing reproductive isolation. However, the results also show that inversions are more likely to be favoured in hybridizing populations among which gene flow is still high, rather than in more strongly isolated populations. This matches the observation that inversions are more frequently observed between sympatric species than between allopatric ones. References [1] Trickett AJ, Butlin RK. 1994. Recombination Suppressors and the Evolution of New Species. Heredity 73:339-345. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1994.180 [2] Dagilis AJ, Kirkpatrick M. 2016. Prezygotic isolation, mating preferences, and the evolution of chromosomal inversions. Evolution 70: 1465–1472. doi: 10.1111/evo.12954 | Prezygotic isolation, mating preferences, and the evolution of chromosomal inversions | Dagilis AJ, Kirkpatrick M | Chromosomal inversions are frequently implicated in isolating species. Models have shown how inversions can evolve in the context of postmating isolation. Inversions are also frequently associated with mating preferences, a topic that has not been... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Denis Roze | 2016-12-13 22:11:54 | View | |

28 Aug 2019

Is adaptation limited by mutation? A timescale-dependent effect of genetic diversity on the adaptive substitution rate in animalsMarjolaine Rousselle, Paul Simion, Marie-Ka Tilak, Emeric Figuet, Benoit Nabholz, Nicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/643619To tinker, evolution needs a supply of spare partsRecommended by Georgii Bazykin based on reviews by Konstantin Popadin, David Enard and 1 anonymous reviewerIs evolution adaptive? Not if there is no variation for natural selection to work with. Theory predicts that how fast a population can adapt to a new environment can be limited by the supply of new mutations coming into it. This supply, in turn, depends on two things: how often mutations occur and in how many individuals. If there are few mutations, or few individuals in whom they can originate, individuals will be mostly identical in their DNA, and natural selection will be impotent. References [1] G, J. A., Visser, M. de, Zeyl, C. W., Gerrish, P. J., Blanchard, J. L., and Lenski, R. E. (1999). Diminishing Returns from Mutation Supply Rate in Asexual Populations. Science, 283(5400), 404–406. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.404 | Is adaptation limited by mutation? A timescale-dependent effect of genetic diversity on the adaptive substitution rate in animals | Marjolaine Rousselle, Paul Simion, Marie-Ka Tilak, Emeric Figuet, Benoit Nabholz, Nicolas Galtier | <p>Whether adaptation is limited by the beneficial mutation supply is a long-standing question of evolutionary genetics, which is more generally related to the determination of the adaptive substitution rate and its relationship with the effective... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Georgii Bazykin | 2019-05-21 09:49:16 | View | |

23 Jan 2023

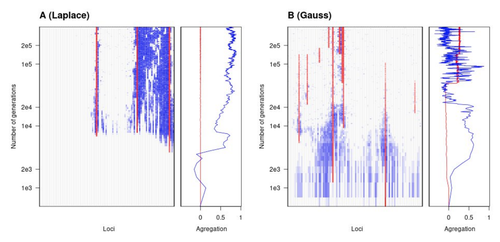

The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a clineFabien Laroche, Thomas Lenormand https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.30.498280Environmental and fitness landscapes matter for the genetic basis of local adaptationRecommended by Charles Mullon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Natural landscapes are often composite, with spatial variation in environmental factors being the norm rather than exception. Adaptation to such variation is a major driver of diversity at all levels of biological organization, from genes to phenotypes, species and ultimately ecosystems. While natural selection favours traits that show a better fit to local conditions, the genomic response to such selection is not necessarily straightforward. This is because many quantitative traits are complex and the product of many loci, each with a small to moderate phenotypic contribution. Adapting to environmental challenges that occur in narrow ranges may thus prove difficult as each individual locus is easily swamped by alleles favoured across the rest of the population range. To better understand whether and how evolution overcomes such a hurdle, Laroche and Lenormand [1] combine quantitative genetics and population genetic modelling to track genomic changes that underpin a trait whose fitness optimum differs between a certain spatial range, referred to as a “pocket”, and the rest of the habitat. As it turns out from their analysis, one critical and probably underappreciated factor in determining the type of genetic architecture that evolves is how fitness declines away from phenotypic optima. One classical and popular model of fitness landscape that relates trait value to reproductive success is Gaussian, whereby small trait variations away from the optimum result in even smaller variations in fitness. This facilitates local adaptation via the invasion of alleles of small effects as carriers inside the pocket show a better fit while those outside the pocket only suffer a weak fitness cost. By contrast, when the fitness landscape is more peaked around the optimum, for instance where the decline is linear, adaptation through weak effect alleles is less likely, requiring larger pockets that are less easily swamped by alleles selected in the rest of the range. In addition to mathematically investigating the initial emergence of local adaptation, Laroche and Lenormand use computer simulations to look at its long-term maintenance. In principle, selection should favour a genetic architecture that consolidates the phenotype and increases its heritability, for instance by grouping several alleles of large effects close to one another on a chromosome to avoid being broken down by meiotic recombination. Whether or not this occurs also depends on the fitness landscape. When the landscape is Gaussian, the genetic architecture of the trait eventually consists of tightly linked alleles of large effects. The replacement of small effects by large effects loci is here again promoted by the slow fitness decline around the optimum. This is because any shift in architecture in an adapted population requires initially crossing a fitness valley. With a Gaussian landscape, this valley is shallow enough to be crossed, facilitated by a bit of genetic drift. By contrast, when fitness declines linearly around the optimum, genetic architecture is much less evolutionarily labile as any architecture change initially entails a fitness cost that is too high to bear. Overall, Laroche and Lenormand provide a careful and thought-provoking analysis of a classical problem in population genetics. In addition to questioning some longstanding modelling assumptions, their results may help understand why differentiated populations are sometimes characterized by “genomic islands” of divergence, and sometimes not. References [1] Laroche F, Lenormand T (2022) The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a cline. bioRxiv, 2022.06.30.498280, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.30.498280 | The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a cline | Fabien Laroche, Thomas Lenormand | <p>Local adaptation is pervasive. It occurs whenever selection favors different phenotypes in different environments, provided that there is genetic variation for the corresponding traits and that the effect of selection is greater than the effect... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics | Charles Mullon | 2022-07-07 08:46:47 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer