Latest recommendations

| Id | Title▲ | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

04 Sep 2019

The discernible and hidden effects of clonality on the genotypic and genetic states of populations: improving our estimation of clonal ratesSolenn Stoeckel, Barbara Porro, Sophie Arnaud-Haond https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.09365v4How to estimate clonality from genetic data: use large samples and consider the biology of the speciesRecommended by Myriam Heuertz based on reviews by David Macaya-Sanz, Marcela Van Loo and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by David Macaya-Sanz, Marcela Van Loo and 1 anonymous reviewer

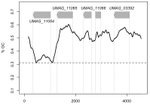

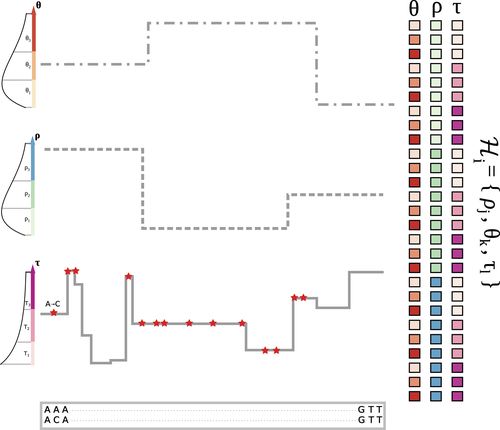

Population geneticists frequently use the genetic and genotypic information of a population sample of individuals to make inferences on the reproductive system of a species. The detection of clones, i.e. individuals with the same genotype, can give information on whether there is clonal (vegetative) reproduction in the species. If clonality is detected, population geneticists typically use genotypic richness R, the number of distinct genotypes relative to the sample size, to estimate the rate of clonality c, which can be defined as the proportion of reproductive events that are clonal. Estimating the rate of clonality based on genotypic richness is however problematic because, to date, there is no analytical, nor simulation-based, characterization of this relationship. Furthermore, the effect of sampling on this relationship has never been critically examined. References [1] Stoeckel, S., Porro, B., and Arnaud-Haond, S. (2019). The discernible and hidden effects of clonality on the genotypic and genetic states of populations: improving our estimation of clonal rates. ArXiv:1902.09365 [q-Bio] v4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1902.09365v4 | The discernible and hidden effects of clonality on the genotypic and genetic states of populations: improving our estimation of clonal rates | Solenn Stoeckel, Barbara Porro, Sophie Arnaud-Haond | <p>Partial clonality is widespread across the tree of life, but most population genetics models are conceived for exclusively clonal or sexual organisms. This gap hampers our understanding of the influence of clonality on evolutionary trajectories... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Myriam Heuertz | 2019-02-28 10:10:56 | View | |

05 Jun 2018

The dynamics of preferential host switching: host phylogeny as a key predictor of parasite prevalence and distributionJan Engelstaedter & Nicole Fortuna https://doi.org/10.1101/209254Shift or stick? Untangling the signatures of biased host switching, and host-parasite co-speciationRecommended by Lucy Weinert based on reviews by Damien de Vienne and Nathan MeddMany emerging diseases arise by parasites switching to new host species, while other parasites seem to remain with same host lineage for very long periods of time, even over timescales where an ancestral host species splits into two or more new species. The ability to understand these dynamics would form an important part of our understanding of infectious disease. Experiments are clearly important for understanding these processes, but so are comparative studies, investigating the variation that we find in nature. Such comparative data do show strong signs of non-randomness, and this suggests that the epidemiological and ecological processes might be predictable, at least in part. For example, when we map patterns of parasite presence/absence onto host phylogenies, we often find that certain host clades harbour many more parasites than expected, or that closely-related hosts harbour closely-related parasites. Nevertheless, it remains difficult to interpret these patterns to make inferences about ecological and epidemiological processes. This is partly because non-random associations can arise in multiple ways. For example, parasites might be inherited from the common ancestor of related hosts, or might switch to new hosts, but preferentially establish on novel hosts that are closely related to their existing host. Infection might also influence the shape of host phylogeny, either by increasing the rate of host extinction or, conversely, increasing the rate of speciation (as with manipulative symbionts that might induce reproductive isolation). These various processes have, by and large, been studied in isolation, but the model introduced by Engelstädter and Fortuna [1], makes an important first step towards studying them together. Without such combined analyses, we will not be able to tell if the processes have their own unique signatures, or whether the same sort of non-randomness can arise in multiple ways. A major finding of the work is that the size of a host clade can be an important determinant of its overall infection level. This had been shown in previous work, assuming that the host phylogeny was fixed, but the current paper shows that it extends also to situations where host extinction and speciation takes place at a comparable rate to host shifting. This finding, then, calls into question the natural assumption that a clade of host species that is highly parasite ridden, must have some genetic or ecological characteristic that makes them particularly prone to infection, arguing that the clade size, rather than any characteristic of the clade members, might be the important factor. It will be interesting to see whether this prediction about clade size is borne out with comparative studies. Another feature of the study is that the framework is naturally extendable, to include further processes, such as the influence of parasite presence on extinction or speciation rates. No doubt extensions of this kind will form the basis of important future work. References [1] Engelstädter J and Fortuna NZ. 2018. The dynamics of preferential host switching: host phylogeny as a key predictor of parasite prevalence and distribution. bioRxiv 209254 ver. 5 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/209254 | The dynamics of preferential host switching: host phylogeny as a key predictor of parasite prevalence and distribution | Jan Engelstaedter & Nicole Fortuna | <p>New parasites commonly arise through host-shifts, where parasites from one host species jump to and become established in a new host species. There is much evidence that the probability of host-shifts decreases with increasing phylogenetic dist... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory, Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Species interactions | Lucy Weinert | 2017-10-30 02:06:06 | View | |

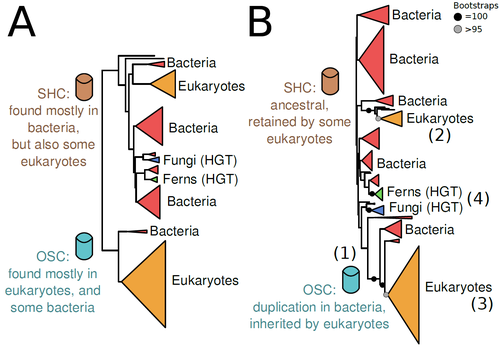

11 Oct 2022

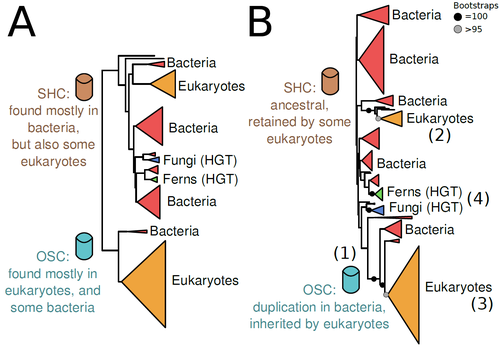

The Eukaryotic Last Common Ancestor Was Bifunctional for Hopanoid and Sterol ProductionWarren R Francis https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202004.0186.v5Gene family analysis suggests new evolutionary scenario for sterol and hopanoid biomarkersRecommended by Iker Irisarri based on reviews by Samuel Abalde, Denis Baurain and Jose Ramon Pardos-BlasSterols and hopanoids are sometimes used as biomarkers to infer the origin of certain groups of organisms. Traditionally, hopanoid-derived products in ancient rocks have been considered to indicate the presence of bacteria, whereas sterol derivatives have been considered to be exclusive to eukaryotes. However, a closer look at the topic reveals a rather complex distribution of either compound in both bacteria and eukaryotes. (1). The known biosynthetic pathways for sterols and hopanoids are similar but diverge at a critical step where two different enzymes are used: squalene-hopene cyclase (SHC) and oxidosqualene cyclase (OSC), the latter requiring oxygen. These two enzymes belong to the same gene family, whose complex evolutionary history is difficult to reconcile with the known species phylogeny. In this study (2), Dr. Warren R. Francis revisits the evolution of this gene family using an extended dataset with a broader taxonomic representation. In contrast to the traditional representation of the tree rooted between SHC and OSC paralogs (i.e., based on function), the author proposes that rooting the tree within bacterial SHCs and assuming a secondary origin of OSC is more parsimonious. This postulates SHC to be the ancestral function –retained in many extant bacteria and some eukaryotes– and OSC to have emerged later within bacteria –currently being mostly present in eukaryotes–. The reconstructed evolutionary history is arguably complex and can only be reconciled with the species' phylogeny by invoking many secondary losses. These losses are considered likely because many extant species acquire sterols and hopanoids by diet and lack one or both enzymes. Some cases of recent horizontal gene transfer are also proposed. In contrast to the dichotomy between bacterial SHCs and eukaryote OSCs, the new proposed scenario suggests that the eukaryote ancestor likely inherited both enzymes from bacteria and thus could be able to synthesize both sterols and hopanoids. Under this hypothesis, not only bacteria but also eukaryotes could be responsible for the hopane found in old rocks. This agrees with eukaryote fossils dating back to more than 1 billion years ago (3). Also, the observed increase of sterane levels in rocks ~600-700 million years old cannot be associated with the origin of eukaryotes, which is a much older event, but could rather reflect changes in atmospheric oxygen levels because oxygen is required for the synthesis of sterols by OSC. References 1. Santana-Molina C, Rivas-Marin E, Rojas AM, Devos DP (2020) Origin and Evolution of Polycyclic Triterpene Synthesis. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 37, 1925–1941. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa054 2. Francis WR (2022) The Eukaryotic Last Common Ancestor Was Bifunctional for Hopanoid and Sterol Production. Preprints, 2020040186, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202004.0186.v5 3. Butterfield NJ (2000) Bangiomorpha pubescens n. gen., n. sp.: implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity, and the Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes. Paleobiology, 26, 386–404. https://doi.org/10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0386:BPNGNS>2.0.CO;2 | The Eukaryotic Last Common Ancestor Was Bifunctional for Hopanoid and Sterol Production | Warren R Francis | <p>Steroid and hopanoid biomarkers can be found in ancient rocks and may give a glimpse of what life was present at that time. Sterols and hopanoids are produced by two related enzymes, though the evolutionary history of this protein family is com... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Molecular Evolution, Paleontology, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Iker Irisarri | 2021-01-13 16:03:29 | View | |

03 Oct 2023

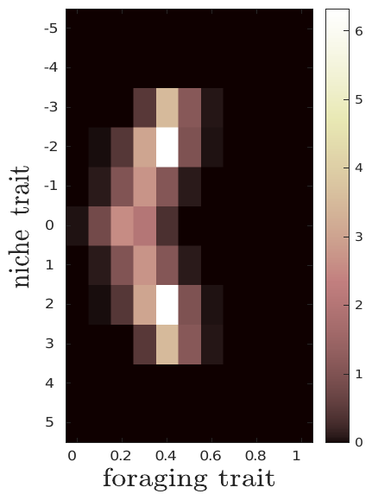

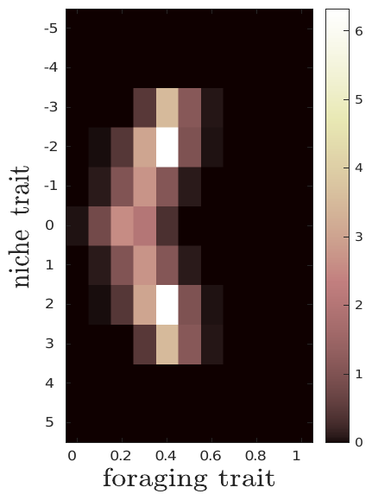

The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer modelLéo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Océane Guillot, Erwan Faou, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Ibanez https://doi.org/10.32942/X2QG7MEvolution and consequences of plastic foraging behavior in consumer-resource ecosystemsRecommended by François Rousset based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersPlastic responses of organisms to their environment may be maladaptive in particular when organisms are exposed to new environments. Phenotypic plasticity may also have opposite effects on the adaptive response of organisms to environmental changes: whether phenotypic plasticity favors or hinders such adaptation depends on a balance between the ability of the population to respond to the change non-genetically in the short term, and the weakened genetic response to environmental change. These topics have received continued attention, particularly in the context of climate change (e.g., Chevin et al. 2013, Duputié et al., 2015, Vinton et al . 2022). In their work, Ledru et al. focus on the adaptive nature of plastic behavior and on its consequences in a consumer-resource ecosystem. As they emphasize, previous works have found that plastic foraging promotes community stability, but these did not consider plasticity as an evolving trait, so Ledru et al. set out to test whether this conclusion holds when both plastic foraging and niche traits of consumers and resources evolve (though ultimately, their new conclusions may not all depend on plasticity evolving). Along the way, they first seek to clarify when such plasticity will evolve, and how it affects the evolution of the niche diversity of consumers and resources, before turning to the question of consumer persistence. The model is rather complex, as three traits are allowed to evolve, and the resource uptake expressed through plastic behavior has its own dynamics affected by some form of social learning. Classically, in models of niche evolution, a consumer's efficiency in exploiting a resource characterized by a trait y (here, the resource's individual niche trait), has been described in terms of location-scale (typically Gaussian) kernels, with mean x (the consumer's individual niche trait) specifying the most efficiently exploited resource, and with variance characterizing individual niche breadth. The evolution of the variance has been considered in some previous models but is assumed to be fixed here. Rather, the new model considers the evolution of the distribution of resource traits, of the consumer's individual niche trait (which is not plastic), and of a "plastic foraging trait" that controls the relative time spent foraging plastically versus foraging randomly. When foraging plastically, the consumers modify their foraging effort towards the type of resource that maximizes their energy intake. in some previous models, the effect of variation in the extent of plastic foraging was already considered, but the evolution of allocation to a plastic foraging strategy versus random foraging was not considered. The model is formulated through reaction-diffusion equations, and its dynamics is investigated by numerical integration. Foraging plasticity readily evolves, when resources vary widely enough, competition for resources is strong, and the cost of plasticity is weak. This means in particular that a large individual niche width of consumers selects for increased plastic foraging, as the evolution of plastic foraging leads to reduced niche overlap between consumers. The evolution of plastic foraging itself generally, though not always, favors the diversification of the niche traits of consumers and of resources. There is thus a positive feedback loop between plastic foraging and resource diversity. Ledru et al. conclude that the total niche width of the consumer population should also correlate with the evolution of plastic foraging, an implication which they relate to the so-called niche variation hypothesis and to empirical tests of it. The joint evolution of the consumer's individual niche trait and plastic foraging trait generates a striking pattern within populations: consumers whose individual niche trait is at an edge of the resource distribution forage more plastically. The authors observe that this relatively simple prediction has not been subjected to any empirical test. Returning to the question of consumer persistence, Ledru et al. evaluate this persistence when consumer mortality increases, and in response to either gradual or sudden environmental changes. These different perturbations all reduce the benefits of plastic foraging. The effect of plastic foraging on stability are complex, being negative or positive effect depending on the type of disturbance, and in particular the ecosystem has a lower sustainable rate of environmental change in the presence of plastic foraging. However, allowing the evolutionary regression of plastic foraging then has a comparatively positive effect on persistence. Despite the substantial effort devoted to analyzing this complex model, relaxing some of its assumptions would likely reveal further complexities. Notably, the overall effect of plasticity on consumer persistence depends on effects already encountered in models of the adaptive response of single species to environmental change: a fast non-genetic response in the short term versus a weakened genetic response in the longer term. The overall balance between these opposite effects on adaptation may be difficult to predict robustly. In the case of a constant rate of environmental change, the results of the present model depend on a lag load between the trait changes of consumer and resource populations, and the extent of the lag may also depend on many factors, such as the extent of genetic variation (e.g., Bürger & Lynch, 1995) for niche traits in consumers and resources. Here, the same variance of mutational effects was assumed for all three evolving traits. Further, spatial environmental variation, a central issue in studies of adaptive responses to environmental changes (e.g., Parmesan, 2006, Zhu et al., 2012), was not considered. Finally, the rate of adjustment of effort by consumers with given niche trait and plastic foraging trait values was assumed proportional to the density of consumers with such trait values. This was justified as a way of accounting for the use of social cues during foraging, but to the extent that they occur, social effects could manifest themselves through other learning dynamics. In conclusion, Ledru et al. have addressed a broad range of questions, suggesting new empirical tests of behavioural patterns on one side, and recovering in the context of community response to environmental changes a complexity that could be expected from earlier works on adaptive responses of organisms but that has been overlooked by previous works on community effects of phenotypic plasticity. References Bürger, R. and Lynch, M. (1995), Evolution and extinction in a changing environment: a quantitative-genetic analysis. Evolution, 49: 151-163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1995.tb05967.x Chevin, L.-M., Collins, S. and Lefèvre, F. (2013), Phenotypic plasticity and evolutionary demographic responses to climate change: taking theory out to the field. Funct Ecol, 27: 967-979. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02043.x Duputié, A., Rutschmann, A., Ronce, O. and Chuine, I. (2015), Phenological plasticity will not help all species adapt to climate change. Glob Change Biol, 21: 3062-3073. https://doi-org.inee.bib.cnrs.fr/10.1111/gcb.12914 Ledru, L., Garnier, J., Guillot, O., Faou, E., & Ibanez, S. (2023). The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer model. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2QG7M Parmesan, C. (2006) Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change Vinton, A.C., Gascoigne, S.J.L., Sepil, I., Salguero-Gómez, R., (2022) Plasticity’s role in adaptive evolution depends on environmental change components. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 37: 1067-1078. Zhu, K., Woodall, C.W. and Clark, J.S. (2012), Failure to migrate: lack of tree range expansion in response to climate change. Glob Change Biol, 18: 1042-1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02571.x | The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer model | Léo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Océane Guillot, Erwan Faou, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Ibanez | <p style="text-align: justify;">Phenotypic plasticity has important ecological and evolutionary consequences. In particular, behavioural phenotypic plasticity such as plastic foraging (PF) by consumers, may enhance community stability. Yet little ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | François Rousset | 2023-03-25 12:04:08 | View | |

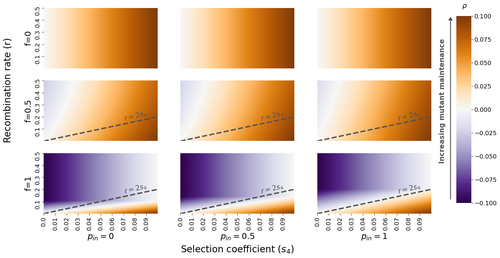

18 Jan 2023

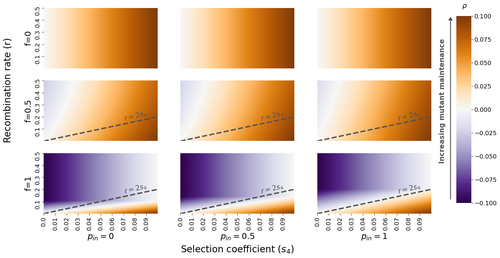

The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfingEmilie Tezenas, Tatiana Giraud, Amandine Veber, Sylvain Billiard https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.07.511119Maintenance of deleterious mutations and recombination suppression near mating-type loci under selfingRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe causes and consequences of the evolution of sexual reproduction are a major topic in evolutionary biology. With advances in sequencing technology, it becomes possible to compare sexual chromosomes across species and infer the neutral and selective processes shaping polymorphism at these chromosomes. Most sex and mating-type chromosomes exhibit an absence of recombination in large genomic regions around the animal, plant or fungal sex-determining genes. This suppression of recombination likely occurred in several time steps generating stepwise increasing genomic regions starting around the sex-determining genes. This mechanism generates so-called evolutionary strata of differentiation between sex chromosomes (Nicolas et al., 2004, Bergero and Charlesworth, 2009, Hartmann et al. 2021). The evolution of extended regions of recombination suppression is also documented on mating-type chromosomes in fungi (Hartmann et al., 2021) and around supergenes (Yan et al., 2020, Jay et al., 2021). The exact reason and evolutionary mechanisms for this phenomenon are still, however, debated. Two hypotheses are proposed: 1) sexual antagonism (Charlesworth et al., 2005), which, nevertheless, does explain the observed occurrence of the evolutionary strata, and 2) the sheltering of deleterious alleles by inversions carrying a lower load than average in the population (Charlesworth and Wall, 1999, Antonovics and Abrams, 2004). In the latter, the mechanism is as follows. A genetic inversion or a suppressor of recombination in cis may exhibit some overdominance behaviour. The inversion exhibiting less recessive deleterious mutations (compared to others at the same locus) may increase in frequency, before at higher frequency occurring at the homozygous state, expressing its genetic load. However, the inversion may never be at the homozygous state if it is genetically linked to a gene in a permanently heterozygous state. The inversion can then be advantageous and may reach fixation at the sex chromosome (Charlesworth and Wall, 1999, Antonovics and Abrams, 2004, Jay et al., 2022). These selective mechanisms promote thus the suppression of recombination around the sex-determining gene, and recessive deleterious mutations are permanently sheltered. This hypothesis is corroborated by the sheltering of deleterious mutations observed around loci under balancing selection (Llaurens et al. 2009, Lenz et al. 2016) and around mating-type genes in fungi and supergenes (Jay et al. 2021, Jay et al., 2022). In this present theoretical study, Tezenas et al. (2022) analyse how linkage to a necessarily heterozygous fungal mating type locus influences the persistence/extinction time of a new mutation at a second selected locus. This mutation can either be deleterious and recessive, or overdominant. There is arbitrary linkage between the two loci, and sexual reproduction occurs either between 1) gametes of different individuals (outcrossing), or 2) by selfing with gametes originating from the same (intra-tetrad) or different (inter-tetrad) tetrads produced by that individual. Note, here, that the mating-type gene does not prevent selfing. The authors study the initial stochastic dynamics of the mutation using a multi-type branching process (and simulations when analytical results cannot be obtained) to compute the extinction time of the deleterious mutation. The main result is that the presence of a mating-type locus always decreases the purging probability and increases the purging time of the mutations under selfing. Ultimately, deleterious mutations can indeed accumulate near the mating-type locus over evolutionary time scales. In a nutshell, high selfing or high intra-tetrad mating do increase the sheltering effect of the mating-type locus. In effect, the outcome of sheltering of deleterious mutations depends on two opposing mechanisms: 1) a higher selfing rate induces a greater production of homozygotes and an increased effect of the purging of deleterious mutations, while 2) a higher intra-tetrad selfing rate (or linkage with the mating-type locus) generates heterozygotes which have a small genetic load (and are favoured). The authors also show that rare events of extremely long maintenance of deleterious mutations can occur. The authors conclude by highlighting the manifold effect of selfing which reduces the effective population size and thus impairs the efficiency of selection and increases the mutational load, while also favouring the purge of deleterious homozygous mutations. Furthermore, this study emphasizes the importance of studying the maintenance and accumulation of deleterious mutations in the vicinity of heterozygous loci (e.g. under balancing selection) in selfing species. References Antonovics J, Abrams JY (2004) Intratetrad Mating and the Evolution of Linkage Relationships. Evolution, 58, 702–709. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00403.x Bergero R, Charlesworth D (2009) The evolution of restricted recombination in sex chromosomes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 24, 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.09.010 Charlesworth D, Morgan MT, Charlesworth B (1990) Inbreeding Depression, Genetic Load, and the Evolution of Outcrossing Rates in a Multilocus System with No Linkage. Evolution, 44, 1469–1489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb03839.x Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B, Marais G (2005) Steps in the evolution of heteromorphic sex chromosomes. Heredity, 95, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800697 Charlesworth B, Wall JD (1999) Inbreeding, heterozygote advantage and the evolution of neo–X and neo–Y sex chromosomes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 266, 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1999.0603 Hartmann FE, Duhamel M, Carpentier F, Hood ME, Foulongne-Oriol M, Silar P, Malagnac F, Grognet P, Giraud T (2021) Recombination suppression and evolutionary strata around mating-type loci in fungi: documenting patterns and understanding evolutionary and mechanistic causes. New Phytologist, 229, 2470–2491. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17039 Jay P, Chouteau M, Whibley A, Bastide H, Parrinello H, Llaurens V, Joron M (2021) Mutation load at a mimicry supergene sheds new light on the evolution of inversion polymorphisms. Nature Genetics, 53, 288–293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-00771-1 Jay P, Tezenas E, Véber A, Giraud T (2022) Sheltering of deleterious mutations explains the stepwise extension of recombination suppression on sex chromosomes and other supergenes. PLOS Biology, 20, e3001698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001698 Lenz TL, Spirin V, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR (2016) Excess of Deleterious Mutations around HLA Genes Reveals Evolutionary Cost of Balancing Selection. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 33, 2555–2564. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw127 Llaurens V, Gonthier L, Billiard S (2009) The Sheltered Genetic Load Linked to the S Locus in Plants: New Insights From Theoretical and Empirical Approaches in Sporophytic Self-Incompatibility. Genetics, 183, 1105–1118. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.109.102707 Nicolas M, Marais G, Hykelova V, Janousek B, Laporte V, Vyskot B, Mouchiroud D, Negrutiu I, Charlesworth D, Monéger F (2004) A Gradual Process of Recombination Restriction in the Evolutionary History of the Sex Chromosomes in Dioecious Plants. PLOS Biology, 3, e4. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0030004 Tezenas E, Giraud T, Véber A, Billiard S (2022) The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfing. bioRxiv, 2022.10.07.511119, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.07.511119 Yan Z, Martin SH, Gotzek D, Arsenault SV, Duchen P, Helleu Q, Riba-Grognuz O, Hunt BG, Salamin N, Shoemaker D, Ross KG, Keller L (2020) Evolution of a supergene that regulates a trans-species social polymorphism. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 240–249. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-1081-1 | The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfing | Emilie Tezenas, Tatiana Giraud, Amandine Veber, Sylvain Billiard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Large regions of suppressed recombination having extended over time occur in many organisms around genes involved in mating compatibility (sex-determining or mating-type genes). The sheltering of deleterious alleles... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Aurelien Tellier | 2022-10-10 13:50:30 | View | |

23 Jan 2023

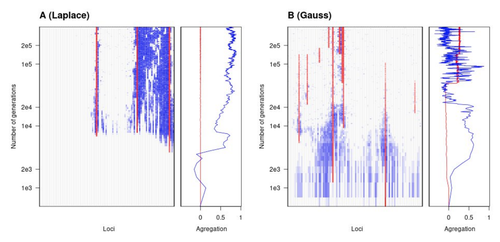

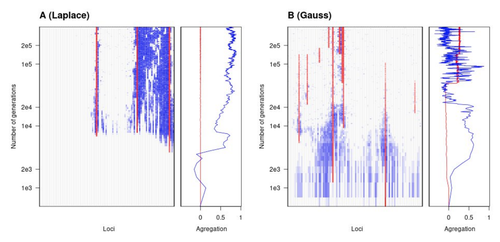

The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a clineFabien Laroche, Thomas Lenormand https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.30.498280Environmental and fitness landscapes matter for the genetic basis of local adaptationRecommended by Charles Mullon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Natural landscapes are often composite, with spatial variation in environmental factors being the norm rather than exception. Adaptation to such variation is a major driver of diversity at all levels of biological organization, from genes to phenotypes, species and ultimately ecosystems. While natural selection favours traits that show a better fit to local conditions, the genomic response to such selection is not necessarily straightforward. This is because many quantitative traits are complex and the product of many loci, each with a small to moderate phenotypic contribution. Adapting to environmental challenges that occur in narrow ranges may thus prove difficult as each individual locus is easily swamped by alleles favoured across the rest of the population range. To better understand whether and how evolution overcomes such a hurdle, Laroche and Lenormand [1] combine quantitative genetics and population genetic modelling to track genomic changes that underpin a trait whose fitness optimum differs between a certain spatial range, referred to as a “pocket”, and the rest of the habitat. As it turns out from their analysis, one critical and probably underappreciated factor in determining the type of genetic architecture that evolves is how fitness declines away from phenotypic optima. One classical and popular model of fitness landscape that relates trait value to reproductive success is Gaussian, whereby small trait variations away from the optimum result in even smaller variations in fitness. This facilitates local adaptation via the invasion of alleles of small effects as carriers inside the pocket show a better fit while those outside the pocket only suffer a weak fitness cost. By contrast, when the fitness landscape is more peaked around the optimum, for instance where the decline is linear, adaptation through weak effect alleles is less likely, requiring larger pockets that are less easily swamped by alleles selected in the rest of the range. In addition to mathematically investigating the initial emergence of local adaptation, Laroche and Lenormand use computer simulations to look at its long-term maintenance. In principle, selection should favour a genetic architecture that consolidates the phenotype and increases its heritability, for instance by grouping several alleles of large effects close to one another on a chromosome to avoid being broken down by meiotic recombination. Whether or not this occurs also depends on the fitness landscape. When the landscape is Gaussian, the genetic architecture of the trait eventually consists of tightly linked alleles of large effects. The replacement of small effects by large effects loci is here again promoted by the slow fitness decline around the optimum. This is because any shift in architecture in an adapted population requires initially crossing a fitness valley. With a Gaussian landscape, this valley is shallow enough to be crossed, facilitated by a bit of genetic drift. By contrast, when fitness declines linearly around the optimum, genetic architecture is much less evolutionarily labile as any architecture change initially entails a fitness cost that is too high to bear. Overall, Laroche and Lenormand provide a careful and thought-provoking analysis of a classical problem in population genetics. In addition to questioning some longstanding modelling assumptions, their results may help understand why differentiated populations are sometimes characterized by “genomic islands” of divergence, and sometimes not. References [1] Laroche F, Lenormand T (2022) The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a cline. bioRxiv, 2022.06.30.498280, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.30.498280 | The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a cline | Fabien Laroche, Thomas Lenormand | <p>Local adaptation is pervasive. It occurs whenever selection favors different phenotypes in different environments, provided that there is genetic variation for the corresponding traits and that the effect of selection is greater than the effect... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics | Charles Mullon | 2022-07-07 08:46:47 | View | |

18 May 2020

The insertion of a mitochondrial selfish element into the nuclear genome and its consequencesJulien Y. Dutheil, Karin Münch, Klaas Schotanus, Eva H. Stukenbrock and Regine Kahmann https://doi.org/10.1101/787044Some evolutionary insights into an accidental homing endonuclease passage from mitochondria to the nucleusRecommended by Sylvain Charlat based on reviews by Jan Engelstaedter and Yannick WurmNot all genetic elements composing genomes are there for the benefit of their carrier. Many have no consequences on fitness, or too mild ones to be eliminated by selection, and thus stem from neutral processes. Many others are indeed the product of selection, but one acting at a different level, increasing the fitness of some elements of the genome only, at the expense of the “organism” as a whole. These can be called selfish genetic elements, and come into a wide variety of flavours [1], illustrating many possible means to cheat with “fair” reproductive processes such as meiosis, and thus get overrepresented in the offspring of their hosts. Producing copies of itself through transposition is one such strategy; a very successful one indeed, explaining a large part of the genomic content of many organisms. Killing non carrier gametes following meiosis in heterozygous carriers is another one. Less know and less common is the ability of some elements to turn heterozygous carriers into homozygous ones, that will thus transmit the selfish elements to all offspring instead of half. This is achieved by nucleic sequences encoding so-called “Homing endonucleases” (HEs). These proteins tend to induce double strand breaks of DNA specifically in regions homologous to their own insertion sites. The recombination machinery is such that the intact homologous region, that is, the one carrying the HE sequence, is then used as a template for the reparation of the break, resulting in the effective conversion of a non-carrier allele into a carrier allele. Such elements can also occur in the mitochondrial genomes of organisms where mitochondria are not strictly transmitted by one parent only, offering mitochondrial HEs some opportunities for “homing” into new non carrier genomes. This is the case in yeasts, where HEs were first reported [2,3]. References [1] Burt, A., and Trivers, R. (2006). Genes in Conflict: The Biology of Selfish Genetic Elements. Belknap Press. | The insertion of a mitochondrial selfish element into the nuclear genome and its consequences | Julien Y. Dutheil, Karin Münch, Klaas Schotanus, Eva H. Stukenbrock and Regine Kahmann | <p>Homing endonucleases (HE) are enzymes capable of cutting DNA at highly specific target sequences, the repair of the generated double-strand break resulting in the insertion of the HE-encoding gene ("homing" mechanism). HEs are present in all th... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Sylvain Charlat | 2019-09-30 20:34:23 | View | |

25 Mar 2019

The joint evolution of lifespan and self-fertilisationThomas Lesaffre, Sylvain Billiard https://doi.org/10.1101/420877Evolution of selfing & lifespan 2.0Recommended by Thomas Bataillon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersFlowering plants display a staggering diversity of both mating systems and life histories, ranging from almost exclusively selfers to obligate outcrossers, very short-lived annual herbs to super long lived trees. One pervasive pattern that has attracted considerable attention is the tight correlation that is found between mating systems and lifespan [1]. Until recently, theoretical explanations for these patterns have relied on static models exploring the consequences of several non-mutually exclusive important process: levels of inbreeding depression and ability to successfully were center stage. This make sense: successful colonization after long‐distance dispersal is far more likely to happen for self‐compatible than for self‐incompatible individuals in a sexually reproducing species. Furthermore, inbreeding depression (essentially a genetically driven phenomenon) and reproductive insurance are expected to shape the evolution of both mating system and lifespan. References | The joint evolution of lifespan and self-fertilisation | Thomas Lesaffre, Sylvain Billiard | <p>In Angiosperms, there exists a strong association between mating system and lifespan. Most self-fertilising species are short-lived and most predominant or obligate outcrossers are long-lived. This association is generally explained by the infl... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Life History, Reproduction and Sex | Thomas Bataillon | 2018-09-19 10:03:51 | View | |

13 Apr 2023

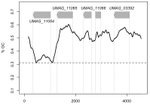

The landscape of nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster is shaped by mutation rate variationGustavo V Barroso, Julien Y Dutheil https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.16.460667An unusual suspect: the mutation landscape as a determinant of local variation in nucleotide diversityRecommended by Fernando Racimo based on reviews by David Castellano and 1 anonymous reviewerSometimes, important factors for explaining biological processes fall through the cracks, and it is only through careful modeling that their importance eventually comes out to light. In this study, Barroso and Dutheil introduce a new method based on the sequentially Markovian coalescent (SMC, Marjoran and Wall 2006) for jointly estimating local recombination and coalescent rates along a genome. Unlike previous SMC-based methods, however, their method can also co-estimate local patterns of variation in mutation rates. This is a powerful improvement which allows them to tackle questions about the reasons for the extensive variation in nucleotide diversity across the chromosomes of a species - a problem that has plagued the minds of population geneticists for decades (Begun and Aquadro 1992, Andolfatto 2007, McVicker et al., 2009, Pouyet and Gilbert 2021). The authors find that variation in de novo mutation rates appears to be the most important factor in determining nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster. Though seemingly contradicting previous attempts at addressing this problem (Comeron 2014), they take care to investigate and explain why that might be the case. Barroso and Dutheil have also taken care to carefully explain the details of their new approach and have carried a very thorough set of analyses comparing competing explanations for patterns of nucleotide variation via causal modeling. The reviewers raised several issues involving choices made by the authors in their analysis of variance partitioning, the proper evaluation of the role of linked selection and the recombination rate estimates emerging from their model. These issues have all been extensively addressed by the authors, and their conclusions seem to remain robust. The study illustrates why the mutation landscape should not be ignored as an important determinant of local variation in genetic diversity, and opens up questions about the generalizability of these results to other organisms. REFERENCES Andolfatto, P. (2007). Hitchhiking effects of recurrent beneficial amino acid substitutions in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome research, 17(12), 1755-1762. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.6691007 Barroso, G. V., & Dutheil, J. Y. (2021). The landscape of nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster is shaped by mutation rate variation. bioRxiv, 2021.09.16.460667, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.16.460667 Begun, D. J., & Aquadro, C. F. (1992). Levels of naturally occurring DNA polymorphism correlate with recombination rates in D. melanogaster. Nature, 356(6369), 519-520. https://doi.org/10.1038/356519a0 Comeron, J. M. (2014). Background selection as baseline for nucleotide variation across the Drosophila genome. PLoS Genetics, 10(6), e1004434. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004434 Marjoram, P., & Wall, J. D. (2006). Fast" coalescent" simulation. BMC genetics, 7, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-7-16 McVicker, G., Gordon, D., Davis, C., & Green, P. (2009). Widespread genomic signatures of natural selection in hominid evolution. PLoS genetics, 5(5), e1000471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000471 Pouyet, F., & Gilbert, K. J. (2021). Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between. Peer Community Journal, 1, e27. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.16 | The landscape of nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster is shaped by mutation rate variation | Gustavo V Barroso, Julien Y Dutheil | <p style="text-align: justify;">What shapes the distribution of nucleotide diversity along the genome? Attempts to answer this question have sparked debate about the roles of neutral stochastic processes and natural selection in molecular evolutio... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics | Fernando Racimo | 2022-10-30 07:52:07 | View | |

30 Aug 2021

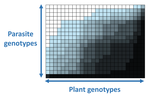

The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactionsMoury Benoît, Audergon Jean-Marc, Baudracco-Arnas Sylvie, Ben Krima Safa, Bertrand François, Boissot Nathalie, Buisson Mireille, Caffier Valérie, Cantet Mélissa, Chanéac Sylvia, Constant Carole, Delmotte François, Dogimont Catherine, Doumayrou Juliette, Fabre Frédéric, Fournet Sylvain, Grimault Valérie, Jaunet Thierry, Justafré Isabelle, Lefebvre Véronique, Losdat Denis, Marcel Thierry C., Montarry Josselin, Morris Cindy E., Omrani Mariem, Paineau Manon, Perrot Sophie, Pilet-Nayel Marie-Laure, R... https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433745Nestedness and modularity in plant-parasite infection networksRecommended by Santiago Elena based on reviews by Rubén González and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Rubén González and 2 anonymous reviewers

In a landmark paper, Flores et al. (2011) showed that the interactions between bacteria and their viruses could be nicely described using a bipartite infection networks. Two quantitative properties of these networks were of particular interest, namely modularity and nestedness. Modularity emerges when groups of host species (or genotypes) shared groups of viruses. Nestedness provided a view of the degree of specialization of both partners: high nestedness suggests that hosts differ in their susceptibility to infection, with some highly susceptible host genotypes selecting for very specialized viruses while strongly resistant host genotypes select for generalist viruses. Translated to the plant pathology parlance, this extreme case would be equivalent to a gene-for-gene infection model (Flor 1956): new mutations confer hosts with resistance to recently evolved viruses while maintaining resistance to past viruses. Likewise, virus mutations for expanding host range evolve without losing the ability to infect ancestral host genotypes. By contrast, a non-nested network would represent a matching-allele infection model (Frank 2000) in which each interacting organism evolves by losing its capacity to resist/infect its ancestral partners, resembling a Red Queen dynamic. Obviously, the reality is more complex and may lie anywhere between these two extreme situations. Recently, Valverde et al. (2020) developed a model to explain the emergence of nestedness and modularity in plant-virus infection networks across diverse habitats. They found that local modularity could coexist with global nestedness and that intraspecific competition was the main driver of the evolution of ecosystems in a continuum between nested-modular and nested networks. These predictions were tested with field data showing the association between plant host species and different viruses in different agroecosystems (Valverde et al. 2020). The effect of interspecific competition in the structure of empirical plant host-virus infection networks was also tested by McLeish et al. (2019). Besides data from agroecosystems, evolution experiments have also shown the pervasive emergence of nestedness during the diversification of independently-evolved lineages of potyviruses in Arabidopsis thaliana genotypes that differ in their susceptibility to infection (Hillung et al. 2014; González et al. 2019; Navarro et al. 2020). In their study, Moury et al. (2021) have expanded all these previous observations to a diverse set of pathosystems that range from viruses, bacteria, oomycetes, fungi, nematodes to insects. While modularity was barely seen in only a few of the systems, nestedness was a common trend (observed in ~94% of all systems). This nestedness, as seen in previous studies and as predicted by theory, emerged as a consequence of the existence of generalist and specialist strains of the parasites that differed in their capacity to infect more or less resistant plant genotypes. As pointed out by Moury et al. (2021) in their conclusions, the ubiquity of nestedness in plant-parasite infection matrices has strong implications for the evolution and management of infectious diseases. References Flor, H. H. (1956). The complementary genic systems in flax and flax rust. In Advances in genetics, 8, 29-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60498-8 Flores, C. O., Meyer, J. R., Valverde, S., Farr, L., and Weitz, J. S. (2011). Statistical structure of host–phage interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, E288-E297. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1101595108 Frank, S. A. (2000). Specific and non-specific defense against parasitic attack. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 202, 283-304. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.1999.1054 González, R., Butković, A., and Elena, S. F. (2019). Role of host genetic diversity for susceptibility-to-infection in the evolution of virulence of a plant virus. Virus evolution, 5(2), vez024. https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/vez052 Hillung, J., Cuevas, J. M., Valverde, S., and Elena, S. F. (2014). Experimental evolution of an emerging plant virus in host genotypes that differ in their susceptibility to infection. Evolution, 68, 2467-2480. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12458 McLeish, M., Sacristán, S., Fraile, A., and García-Arenal, F. (2019). Coinfection organizes epidemiological networks of viruses and hosts and reveals hubs of transmission. Phytopathology, 109, 1003-1010. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-08-18-0293-R Moury B, Audergon J-M, Baudracco-Arnas S, Krima SB, Bertrand F, Boissot N, Buisson M, Caffier V, Cantet M, Chanéac S, Constant C, Delmotte F, Dogimont C, Doumayrou J, Fabre F, Fournet S, Grimault V, Jaunet T, Justafré I, Lefebvre V, Losdat D, Marcel TC, Montarry J, Morris CE, Omrani M, Paineau M, Perrot S, Pilet-Nayel M-L and Ruellan Y (2021) The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactions. bioRxiv, 2021.03.03.433745, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433745 Navarro, R., Ambros, S., Martinez, F., Wu, B., Carrasco, J. L., and Elena, S. F. (2020). Defects in plant immunity modulate the rates and patterns of RNA virus evolution. bioRxiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.13.337402 Valverde, S., Vidiella, B., Montañez, R., Fraile, A., Sacristán, S., and García-Arenal, F. (2020). Coexistence of nestedness and modularity in host–pathogen infection networks. Nature ecology & evolution, 4, 568-577. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1130-9 | The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactions | Moury Benoît, Audergon Jean-Marc, Baudracco-Arnas Sylvie, Ben Krima Safa, Bertrand François, Boissot Nathalie, Buisson Mireille, Caffier Valérie, Cantet Mélissa, Chanéac Sylvia, Constant Carole, Delmotte François, Dogimont Catherine, Doumayrou Jul... | <p>Understanding the relationships between host range and pathogenicity for parasites, and between the efficiency and scope of immunity for hosts are essential to implement efficient disease control strategies. In the case of plant parasites, most... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Species interactions | Santiago Elena | 2021-03-04 21:23:08 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer