Latest recommendations

| Id | Title▲ | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

15 Sep 2022

Bimodal breeding phenology in the Parsley Frog Pelodytes punctatus as a bet-hedging strategy in an unpredictable environment despite strong priority effectsHelene Jourdan-Pineau, Pierre-Andre Crochet, Patrice David https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.24.481784Spreading the risk of reproductive failure when the environment is unpredictable and ephemeralRecommended by Gabriele Sorci based on reviews by Thomas Haaland and Zoltan RadaiMany species breed in environments that are unpredictable, for instance in terms of the availability of resources needed to raise the offspring. Organisms might respond to such spatial and temporal unpredictability by adopting plastic responses to adjust their reproductive investment according to perceived cues of environmental quality. Some species such as the amphibians might also face the problem of ephemeral habitats, when the ponds where they breed have a chance of drying up before metamorphosis has occurred. In this case, maximizing long-term fitness might involve a strategy of spreading the risk, even though the reproductive success of a single reproductive bout might be lower. Understanding how animals (and plants) get adapted to stochastic environments is particularly crucial in the current context of rapid environmental changes. In this article, Jourdan-Pineau et al. report the results of field surveys of the Parsley Frog (Pelodytes punctatus) in Southern France. This frog has peculiar breeding phenology with females breeding in autumn and spring. The authors provide quite an extensive amount of information on the reproductive success of eggs laid in each season and the possible ecological factors accounting for differences between seasons. Although the presence of interspecific competitors and predators does not seem to account for pond-specific reproductive success, the survival of tadpoles hatching from eggs laid in spring is severely impaired when tadpoles from the autumn cohort have managed to survive. This intraspecific competition takes the form of a “priority” effect where tadpoles from the autumn cohort outcompete the smaller larvae from the spring cohort. Given this strong priority effect, one might tentatively predict that females laying in spring should avoid ponds with tadpoles from the autumn cohort. Surprisingly, however, the authors did not find any evidence for such avoidance, which might indicate strong constraints on the availability of ponds where females might possibly lay. Assuming that each female can indeed lay both in autumn and spring, how is this bimodal phenology maintained? Would not be worthier to allocate all the eggs to the autumn (or the spring) laying season? Eggs laid in autumn and spring have to face different environmental hazards, reducing their hatching success and the probability to produce metamorphs (for instance, tadpoles hatching from eggs laid in autumn have to overwinter which might be a particularly risky phase). Jourdan-Pineau and coworkers addressed this question by adapting a bet-hedging model that was initially developed to investigate the strategy of allocation into seed dormancy of annual plants (Cohen 1966) to the case of the bimodal phenology of the Parsley Frog. By feeding the model with the parameter values obtained from the field surveys, they found that the two breeding strategies (laying in autumn and in spring) can coexist as long as the probability of breeding success in the autumn cohort is between 20% and 80% (the range of values allowing the coexistence of a bimodal phenology shrinking a little bit when considering that frogs can reproduce 5 times during their lifespan instead of three times). This paper provides a very nice illustration of the importance of combining approaches (here field monitoring to gather data that can be used to feed models) to understand the evolution of peculiar breeding strategies. Although future work should attempt to gather individual-based data (in addition to population data), this work shows that spreading the risk can be an adaptive strategy in environments characterized by strong stochastic variation. References Cohen D (1966) Optimizing reproduction in a randomly varying environment. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 12, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(66)90188-3 Jourdan-Pineau H., Crochet P.-A., David P. (2022) Bimodal breeding phenology in the Parsley Frog Pelodytes punctatus as a bet-hedging strategy in an unpredictable environment despite strong priority effects. bioRxiv, 2022.02.24.481784, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.24.481784 | Bimodal breeding phenology in the Parsley Frog Pelodytes punctatus as a bet-hedging strategy in an unpredictable environment despite strong priority effects | Helene Jourdan-Pineau, Pierre-Andre Crochet, Patrice David | <p style="text-align: justify;">When environmental conditions are unpredictable, expressing alternative phenotypes spreads the risk of failure, a mixed strategy called bet-hedging. In the southern part of its range, the Parsley Frog <em>Pelodytes ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Gabriele Sorci | 2022-02-28 11:53:00 | View | |

24 Jan 2017

POSTPRINT

Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genomeSébastien Leclercq, Julien Thézé, Mohamed Amine Chebbi, Isabelle Giraud, Bouziane Moumen, Lise Ernenwein, Pierre Grève, Clément Gilbert, and Richard Cordaux 10.1073/pnas.1608979113A newly evolved W(olbachia) sex chromosome in pillbug!Recommended by Gabriel Marais and Sylvain CharlatIn some taxa such as fish and arthropods, closely related species can have different mechanisms of sex determination and in particular different sex chromosomes, which implies that new sex chromosomes are constantly evolving [1]. Several models have been developed to explain this pattern but empirical data are lacking and the causes of the fast sex chromosome turn over remain mysterious [2-4]. Leclerq et al. [5] in a paper that just came out in PNAS have focused on one possible explanation: Wolbachia. This widespread intracellular symbiont of arthropods can manipulate its host reproduction in a number of ways, often by biasing the allocation of resources toward females, the transmitting sex. Perhaps the most spectacular example is seen in pillbugs, where Wolbachia commonly turns infected males into females, thus doubling its effective transmission to grandchildren. Extensive investigations on this phenomenon were initiated 30 years ago in the host species Armadillidium vulgare. The recent paper by Leclerq et al. beautifully validates an hypothesis formulated in these pioneer studies [6], namely, that a nuclear insertion of the Wolbachia genome caused the emergence of new female determining chromosome, that is, a new sex chromosome. Many populations of A. vulgare are infected by the feminising Wolbachia strain wVulC, where the spread of the bacterium has also induced the loss of the ancestral female determining W chromosome (because feminized ZZ individuals produce females without transmitting any W). In these populations, all individuals carry two Z chromosomes, so that the bacterium is effectively the new sex-determining factor: specimens that received Wolbachia from their mother become females, while the occasional loss of Wolbachia from mothers to eggs allows the production of males. Intriguingly, studies from natural populations also report that some females are devoid both of Wolbachia and the ancestral W chromosome, suggesting the existence of new female determining nuclear factor, the hypothetical “f element”. Leclerq et al. [5] found the f element and decrypted its origin. By sequencing the genome of a strain carrying the putative f element, they found that a nearly complete wVulC genome got inserted in the nuclear genome and that the chromosome carrying the insertion has effectively become a new W chromosome. The insertion is indeed found only in females, PCRs and pedigree analysis tell. Although the Wolbachia-derived gene(s) that became sex-determining gene(s) remain to be identified among many possible candidates, the genomic and genetic evidence are clear that this Wolbachia insertion is determining sex in this pillbug strain. Leclerq et al. [5] also found that although this insertion is quite recent, many structural changes (rearrangements, duplications) have occurred compared to the wVulC genome, which study will probably help understand which bacterial gene(s) have retained a function in the nucleus of the pillbug. Also, in the future, it will be interesting to understand how and why exactly the nuclear inserted Wolbachia rose in frequency in the pillbug population and how the cytoplasmic Wolbachia was lost, and to tease apart the roles of selection and drift in this event. We highly recommend this paper, which provides clear evidence that Wolbachia has caused sex chromosome turn over in one species, opening the conjecture that it might have done so in many others. References [1] Bachtrog D, Mank JE, Peichel CL, Kirkpatrick M, Otto SP, Ashman TL, Hahn MW, Kitano J, Mayrose I, Ming R, Perrin N, Ross L, Valenzuela N, Vamosi JC. 2014. Tree of Sex Consortium. Sex determination: why so many ways of doing it? PLoS Biology 12: e1001899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001899 [2] van Doorn GS, Kirkpatrick M. 2007. Turnover of sex chromosomes induced by sexual conflict. Nature 449: 909-912. doi: 10.1038/nature06178 [3] Cordaux R, Bouchon D, Grève P. 2011. The impact of endosymbionts on the evolution of host sex-determination mechanisms. Trends in Genetics 27: 332-341. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.002 [4] Blaser O, Neuenschwander S, Perrin N. 2014. Sex-chromosome turnovers: the hot-potato model. American Naturalist 183: 140-146. doi: 10.1086/674026 [5] Leclercq S, Thézé J, Chebbi MA, Giraud I, Moumen B, Ernenwein L, Grève P, Gilbert C, Cordaux R. 2016. Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genome. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 113: 15036-15041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608979113 [6] Legrand JJ, Juchault P. 1984. Nouvelles données sur le déterminisme génétique et épigénétique de la monogénie chez le crustacé isopode terrestre Armadillidium vulgare Latr. Génétique Sélection Evolution 16: 57–84. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-16-1-57 | Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genome | Sébastien Leclercq, Julien Thézé, Mohamed Amine Chebbi, Isabelle Giraud, Bouziane Moumen, Lise Ernenwein, Pierre Grève, Clément Gilbert, and Richard Cordaux | Sex determination is an evolutionarily ancient, key developmental pathway governing sexual differentiation in animals. Sex determination systems are remarkably variable between species or groups of species, however, and the evolutionary forces und... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Gabriel Marais | 2017-01-13 15:15:51 | View | |

22 May 2017

Can Ebola Virus evolve to be less virulent in humans?Mircea T. Sofonea, Lafi Aldakak, Luis Fernando Boullosa, Samuel Alizon 10.1101/108589A new hypothesis to explain Ebola's high virulenceRecommended by Virginie Ravigné and François Blanquart based on reviews by Virginie Ravigné and François Blanquart

The tragic 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak that resulted in more than 28,000 cases and 11,000 deaths in West Africa [1] has been a surprise to the scientific community. Before 2013, the Ebola virus (EBOV) was known to produce recurrent outbreaks in remote villages near tropical rainforests in Central Africa, never exceeding a few hundred cases with very high virulence. Both EBOV’s ability to circulate for several months in large urban human populations and its important mutation rate suggest that EBOV’s virulence could evolve and to some extent adapt to human hosts [2]. Up to now, the high virulence of EBOV in humans was generally thought to be maladaptive, the virus being adapted to circulating in wild animal populations (e.g. fruit bats [3]). As a logical consequence, EBOV virulence could be expected to decrease during long epidemics in humans. The present paper by Sofonea et al. [4] challenges this view and explores how, given EBOV’s life cycle and known epidemiological parameters, virulence is expected to evolve in the human host during long epidemics. The main finding of the paper is that there is no chance that EBOV’s virulence decreases in the short and long terms. The main underlying mechanism is that EBOV is also transmitted by dead bodies, which limits the cost of virulence. In itself the idea that selection should select for higher virulence in diseases that are also transmitted after host death will sound intuitive for most evolutionary epidemiologists. The accomplishment of the paper is to make a very strong case that the parameter range where virulence could decrease is very small. The paper further provides scientifically grounded arguments in favor of the safe management of corpses. Safe burial of corpses is culturally difficult to impose. The present paper shows that in addition to instantaneously decreasing the spread of the virus, safe burial may limit virulence increase in the short term and favor of less virulent strains in the long term. Altogether these results make a timely and important contribution to the knowledge and understanding of EBOV. References [1] World Health Organization. 2016. WHO: Ebola situation report - 10 June 2016. [2] Kupferschmidt K. 2014. Imagining Ebola’s next move. Science 346: 151–152. doi: 10.1126/science.346.6206.151 [3] Leroy EM, Kumulungui B, Pourrut X, Rouquet P, Hassanin A, Yaba P, Délicat A, Paweska, Gonzalez JP and Swanepoel R. 2005. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 438: 575–576. doi: 10.1038/438575a [4] Sofonea MT, Aldakak L, Boullosa LFVV and Alizon S. 2017. Can Ebola Virus evolve to be less virulent in humans? bioRxiv 108589, ver. 3 of 19th May 2017; doi: 10.1101/108589 | Can Ebola Virus evolve to be less virulent in humans? | Mircea T. Sofonea, Lafi Aldakak, Luis Fernando Boullosa, Samuel Alizon | Understanding Ebola Virus (EBOV) virulence evolution is not only timely but also raises specific questions because it causes one pf the most virulent human infections and it is capable of transmission after the death of its host. Using a compartme... |  | Evolutionary Epidemiology | Virginie Ravigné | 2017-02-15 13:25:58 | View | |

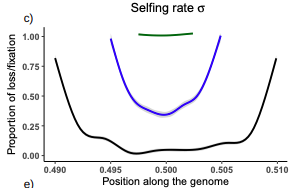

06 Feb 2024

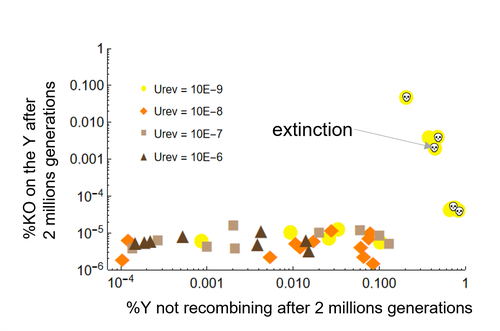

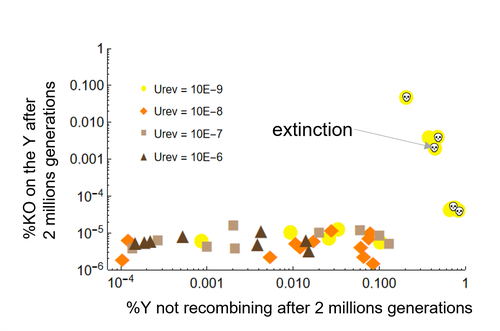

Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes?Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.17.528909New modelling results help understanding the evolution and maintenance of recombination suppression involving sex chromosomesRecommended by Jos Käfer based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersDespite advances in genomic research, many views of genome evolution are still based on what we know from a handful of species, such as humans. This also applies to our knowledge of sex chromosomes. We've apparently been too much used to the situation in which a highly degenerate Y chromosome coexists with an almost normal X chromosome to be able to fully grasp all the questions implied by this situation. Lately, many more sex chromosomes have been studied in other organisms, such as in plants, and the view is changing radically: there is a large diversity of situations, ranging from young highly divergent sex chromosomes to old ones that are so similar that they're hard to detect. Undoubtedly inspired by these recent findings, a few theoretical studies have been published around 2 years ago that put an entirely new light on the evolution of sex chromosomes. The differences between these models have however remained somewhat difficult to appreciate by non-specialists. In particular, the models by Lenormand & Roze (2022) and by Jay et al. (2022) seemed quite similar. Indeed, both rely on the same mechanism for initial recombination suppression: a ``lucky'' inversion, i.e. one with less deleterious mutations than the population average, encompassing the sex-determination locus, is initially selected. However, as it doesn't recombine, it will quickly accumulate deleterious mutations lowering its fitness. And it's at this point the models diverge: according to Lenormand & Roze (2022), nascent dosage compensation not only limits the deleterious effects on fitness by the ongoing degeneration, but it actually opposes recombination restoration as this would lead gene expression away from the optimum that has been reached. On the other hand, in the model by Jay et al. (2022), no additional ingredient is required: they argue that once an inversion had been fixed, reversions that restore recombination are extremely unlikely. This is what Lenormand & Roze (2024) now call a ``constraint'': in Jay et al.'s model, recombination restoration is impossible for mechanistic reasons. Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue such constraints cannot explain long-term recombination suppression. Instead, a mechanism should evolve to limit the negative fitness effects of recombination arrest, otherwise recombination is either restored, or the population goes extinct due to a dramatic drop in the fitness of the heterogametic sex. These two arguments work together: given the huge fitness cost of the lack of ongoing degeneration of the non-recombining Y, in the absence of compensatory mechanisms, there is a very strong selection for the restoration of recombination, so that even when restoration a priori is orders of magnitude less likely than inversion (leading to recombination suppression), it will eventually happen. One way the negative fitness effects of recombination suppression can be limited, is the way the authors propose in their own model: dosage compensation evolves through regulatory evolution right at the start of recombination suppression. This changes our classical, simplistic view that dosage compensation evolves in response to degeneration: rather, Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue, that degeneration can only happen when dosage compensation is effective. The reasoning is convincing and exposes the difference between the models to readers without a firm background in mathematical modelling. Although Lenormand & Roze (2024) target the "constraint theory", it seems likely that other theories for the maintenance of recombination suppression that don't imply the compensation of early degeneration are subject to the same criticism. Indeed, they mention the widely-cited "sexual antagonism" theory, in which mutations with a positive effect in males but a negative in females will select for recombination suppression that will link them to the sex-determining gene on the Y. However, once degeneration starts, the sexually-antagonistic benefits should be huge to overcome the negative effects of degeneration, and it's unlikely they'll be large enough. A convincing argument by Lenormand & Roze (2024) is that there are many ways recombination could be restored, allowing to circumvent the possible constraints that might be associated with reverting an inversion. First, reversions don't have to be exact to restore recombination. Second, the sex-determining locus can be transposed to another chromosome pair, or an entirely new sex-determining locus might evolve, leading to sex-chromosome turnover which has effectively been observed in several groups. These modelling studies raise important questions that need to be addressed with both theoretical and empirical work. First, is the regulatory hypothesis proposed by Lenormand & Roze (2022) the only plausible mechanism for the maintenance of long-term recombination suppression? The female- and male-specific trans regulators of gene expression that are required for this model, are they readily available or do they need to evolve first? Both theoretical work and empirical studies of nascent sex chromosomes will help to answer these questions. However, nascent sex chromosomes are difficult to detect and dosage compensation is difficult to reveal. Second, how many species today actually have "stable" recombination suppression? Maybe many species are in a transient phase, with different populations having different inversions that are either on their way to being fixed or starting to get counterselected. The models have now shown us some possibilities qualitatively but can they actually be quantified to be able to fit the data and to predict whether an observed case of recombination suppression is transient or stable? The debate will continue, and we need the active contribution of theoretical biologists to help clarify the underlying hypotheses of the proposed mechanisms. Conflict of interest statement: I did co-author a manuscript with D. Roze in 2023, but do not consider this a conflict of interest. The manuscript is the product of discussions that have taken place in a large consortium mainly in 2019. It furthermore deals with an entirely different topic of evolutionary biology. References Jay P, Tezenas E, Véber A, and Giraud T. (2022) Sheltering of deleterious mutations explains the stepwise extension of recombination suppression on sex chromosomes and other supergenes. PLoS Biol.;20:e3001698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001698 | Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes? | Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze | <p style="text-align: justify;">Y and W chromosomes often stop recombining and degenerate. Most work on recombination suppression has focused on the mechanisms favoring recombination arrest in the short term. Yet, the long-term maintenance of reco... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Jos Käfer | 2023-10-27 21:52:06 | View | |

18 Dec 2017

Co-evolution of virulence and immunosuppression in multiple infectionsTsukushi Kamiya, Nicole Mideo, Samuel Alizon 10.1101/149211Two parasites, virulence and immunosuppression: how does the whole thing evolve?Recommended by Sara Magalhaes based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersHow parasite virulence evolves is arguably the most important question in both the applied and fundamental study of host-parasite interactions. Typically, this research area has been progressing through the formalization of the problem via mathematical modelling. This is because the question is a complex one, as virulence is both affected and affects several aspects of the host-parasite interaction. Moreover, the evolution of virulence is a problem in which ecology (epidemiology) and evolution (changes in trait values through time) are tightly intertwined, generating what is now known as eco-evolutionary dynamics. Therefore, intuition is not sufficient to address how virulence may evolve. References [1] Anderson RM and May RM. 1982. Coevolution of hosts and parasites. Parasitology, 1982. 85: 411–426. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000055360 [2] Kamiya T, Mideo N and Alizon S. 2017. Coevolution of virulence and immunosuppression in multiple infections. bioRxiv, ver. 7 peer-reviewed by PCI Evol Biol, 149211. doi: 10.1101/139147 | Co-evolution of virulence and immunosuppression in multiple infections | Tsukushi Kamiya, Nicole Mideo, Samuel Alizon | Many components of the host-parasite interaction have been shown to affect the way virulence, that is parasite induced harm to the host, evolves. However, co-evolution of multiple traits is often neglected. We explore how an immunosuppressive mech... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Sara Magalhaes | 2017-06-13 16:49:45 | View | |

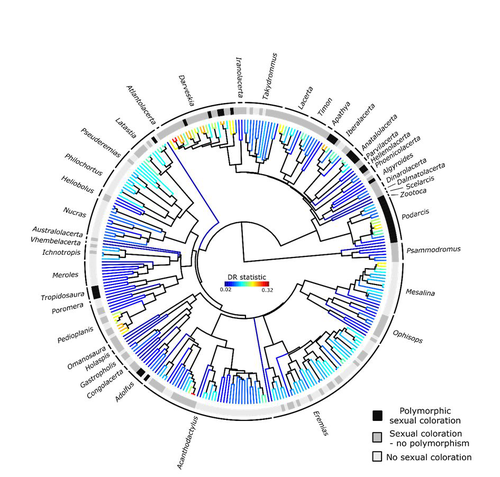

13 Nov 2023

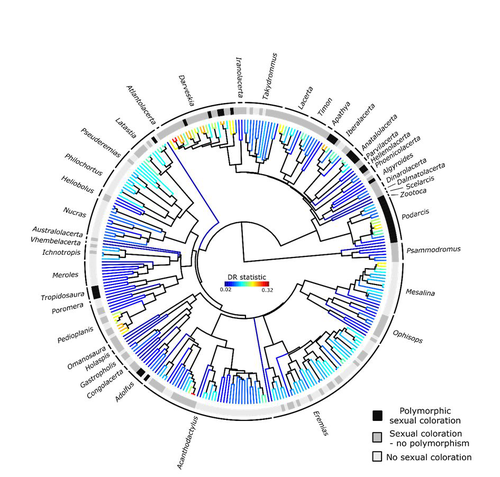

Color polymorphism and conspicuousness do not increase speciation rates in LacertidsThomas de Solan, Barry Sinervo, Philippe Geniez, Patrice David, Pierre-André Crochet https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.15.528678Colour polymorphism does not increase diversification rates in lizardsRecommended by Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe striking differences in species richness among lineages in the Tree of Life have long attracted much research interest. In particular, researchers have asked whether certain traits are associated with greater diversification, with a particular focus on traits under sexual selection given their direct link to mating isolation. Polymorphism, defined as the presence of co-occurring, heritable morphs within a population, has been proposed to influence diversification rates although the effect has been proposed as both promoting or alternatively impeding speciation. The effect of polymorphism may be positive, that is facilitating speciation if polymorphism allows to broaden the ecological niche, thus enabling range expansion, or enabling maintenance of populations in variable environments. Specialized ectomorphs have been observed in several species (e.g. Kusche et al. 2015, Lattanzio and Miles 2016, Whitney et al. 2018, Scali et al. 2016). Polymorphism may also facilitate speciation if a morph is lost during the colonization of a novel area or niche, resulting in rapid divergence of the remaining morphs and reproductive isolation from the ancestral population, known as the morph speciation hypothesis (West-Eberhard 1986, Corl et al. 2010). On the other hand, polymorphism may hamper speciation through disassortative maintaining by morph, which may maintain the polymorphism through the speciation process (Jamie and Meier 2020). An example of such a process is Heliconius numata where disassortative mate preferences based on color hampers ecological speciation (Chouteau et al. 2017). Previous evidence in birds and lizards suggests polymorphism favors diversification (Corl et al. 2010b, 2012, Hugall and Stuart-Fox 2012, Brock et al. 2021). Here, de Solan et al. (2023) test the effect of polymorphism on diversification in Lacertidae, a family of lizards containing more than 300 species distributed across Europe, Africa and Asia. The group offers a good model system to test the effect of polymorphism on speciation as it contains several species with colour polymorphism, sometimes present in both sexes but restricted to males when present in the flank. Using coloration data from the literature as well as photographs of live specimens for 295 species the authors tested whether the presence of polymorphism is associated with higher diversification rates. While undertaking their project, another group independently tackled the same question (Brock et al. 2021), using the same model system but coming to very different conclusions. Therefore, de Solan et al. (2023) decided to also contrast their results with those of Brock et al. (2021) to determine the factors responsible for the contrasting results of both studies. The latter I consider one of the strengths of the work, given the careful re-analyses to determine the causes of the discrepancies between both studies. De Solan et al. (2023) found no association between the presence of polymorphism and diversification rates, even though they used different analytical approaches. Thus, this study is interesting as it provides results that do not support a positive effect of polymorphism on species richness. The use of a phylogeny with more limited species sampling (García-Porta et al. 2019) implied that the authors had to manually add 75 species, of which 17 were added to the tree based on information from previously published trees and 68 were added at random locations within the genus. To control for potential biases the authors repeated the analyses using a sample of trees with the imputed taxa, results were broadly concordant across the set of trees. The careful re-analysis contrasting Brock et al. (2021) and de Solan et al. (2023) results suggests the difference is mainly due to a difference in how species were coded as presenting polymorphism, which differed between the two studies, as well as a difference in the package version used to run the state-dependent diversification models. Interestingly non-parametric analyses yielded similar results across both datasets. Garcia-Porta, J., Irisarri, I., Kirchner, M. et al. 2019. Environmental temperatures shape thermal physiology as well as diversification and genome-wide substitution rates in lizards. Nature Communications. 10: 4077. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11943-x de Solan T, Sinervo B, Geniez P, David P, Crochet P-A (2023) Colour polymorphism and conspicuousness do not increase speciation rates in Lacertids. bioRxiv, 2023.02.15.528678, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.15.528678 West-Eberhard, M.J. 1986. Alternative adaptations, speciation, and phylogeny (A review). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 83: 1388-1392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.83.5.1388 | Color polymorphism and conspicuousness do not increase speciation rates in Lacertids | Thomas de Solan, Barry Sinervo, Philippe Geniez, Patrice David, Pierre-André Crochet | <p style="text-align: justify;">Conspicuous body colors and color polymorphism have been hypothesized to increase rates of speciation. Conspicuous colors are evolutionary labile, and often involved in intraspecific sexual signaling and thus may pr... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Speciation | Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer | 2023-02-22 10:05:03 | View | |

02 Feb 2024

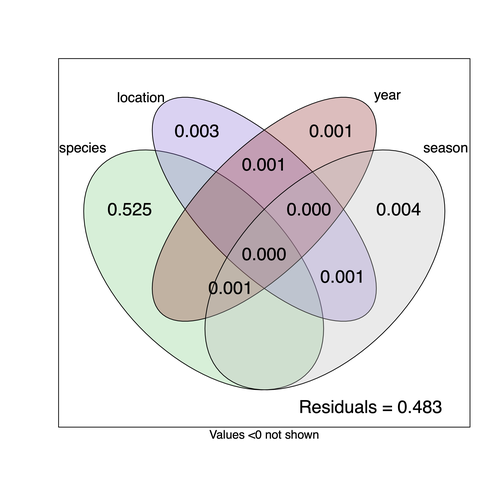

Community structure of heritable viruses in a Drosophila-parasitoids complexJulien Varaldi, David Lepetit, Nelly Burlet, Camille Faber, Bérénice Baretje, Roland Allemand https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.29.551099The virome of a Drosophilidae-parasitoid communityRecommended by Ben Longdon based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Understanding the factors that shape the virome of a host is key to understanding virus ecology and evolution (Obbard, 2018; French & Holmes, 2020). There is still much to learn about the diversity and distribution of viruses in a host community (Wille et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2023). The viruses of parasitoid wasps are well studied, and their viruses, or integrated viral genes, are known to suppress their insect host’s immune response to enhance parasitoid survival (Herniou et al., 2013; Coffman et al., 2022). Likewise, the insect virome is being increasingly well studied (Shi et al., 2016), with the virome of Drosophila species being particularly well characterised over the best part of the last century (L'Heritier & Teissier, 1937; L'Heritier, 1970; Brun & Plus, 1980; Longdon et al., 2010; Longdon et al., 2011; Longdon et al., 2012; Webster et al., 2015; Webster et al., 2016; Medd et al., 2018; Wallace et al., 2021). However, the viromes of parasitoids and their insect host communities have been less well studied (Leigh et al., 2018; Caldas-Garcia et al., 2023), and the inherent connectivity between parasitoids and their hosts provides an interesting system to study virus host range and cross-species transmission. Here, Varaldi et al (Varaldi et al., 2024) have examined the viruses associated with a community of nine Drosophilidae hosts and six parasitoids. Using both RNA and DNA sequencing of insects reared for two generations, they selected viruses that are maintained in the lab either via vertical transmission or contamination of rearing medium. From 55 pools of insects they found 53 virus-like sequences, 37 of which were novel. Parasitoids were host to nearly twice as many viruses as their Drosophila hosts, although they note this could be due to differences in the rearing temperatures of the hosts. They next quantified if species, year, season, or location played a role in structuring the virome, finding only a significant effect of host species, which explained just over 50% of the variation in virus distribution. No evidence was found of related species sharing more similar virus communities. Although looking at a limited number of species, this suggests that these viruses are not co-speciating or preferentially host switching between closely related species. Finally, they carried out crosses between lines of the parasitoid Leptopilina heterotoma that were infected and uninfected for a novel Iflavirus found in their sequencing data. They found evidence of high levels of maternal transmission and lower level horizontal transmission between wasp larvae parasitising the same host. No evidence of changes in parasitoid-induced mortality, developmental success or the sex ratio was found in iflavirus-infected parasitoids. Interestingly individuals infected with this RNA virus also contained viral DNA, but this did not appear to be integrated into the wasp genome. Overall, this work has taken the first steps in examining the community structure of the virome of parasitoids together with their Drosophilidae hosts. This work will not doubt stimulate follow-up studies to explore the evolution and ecology of these novel virus communities. References Brun G, Plus N (1980) The viruses of Drosophila. In: The genetics and biology of Drosophila eds Ashburner M & Wright TRF), pp. 625-702. Academic Press, New York. | Community structure of heritable viruses in a *Drosophila*-parasitoids complex | Julien Varaldi, David Lepetit, Nelly Burlet, Camille Faber, Bérénice Baretje, Roland Allemand | <p style="text-align: justify;">The diversity and phenotypic impacts related to the presence of heritable bacteria in insects have been extensively studied in the last decades. On the contrary, heritable viruses have been overlooked for several re... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Ben Longdon | 2023-08-03 01:07:43 | View | |

16 Dec 2022

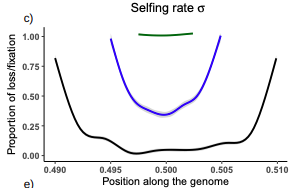

Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depressionDiala Abu Awad, Donald Waller https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.473022Pseudo-overdominance: how linkage and selection can interact and oppose to purging of deleterious mutations.Recommended by Sylvain Glémin based on reviews by Yaniv Brandvain, Lei Zhao and 1 anonymous reviewerMost mutations affecting fitness are deleterious and they have many evolutionary consequences. The dynamics and consequences of deleterious mutations are a long-standing question in evolutionary biology and a strong theoretical background has already been developed, for example, to predict the mutation load, inbreeding depression or background selection. One of the classical results is that inbreeding helps purge partially recessive deleterious mutations by exposing them to selection in homozygotes. However, this mainly results from single-locus considerations. When interactions among several, more or less linked, deleterious mutations are taken into account, peculiar dynamics can emerge. One of them, called pseudo-overdominance (POD), corresponds to the maintenance in a population of two (or more) haplotype blocks composed of several recessive deleterious mutations in repulsion that mimics overdominance. Indeed, homozygote individuals for one of the haplotype blocks expose many deleterious mutations to selection whereas they are reciprocally masked in heterozygotes, leading to higher fitness of heterozygotes compared to both homozygotes. A related process, called associative overdominance (AOD) is the effect of such deleterious alleles in repulsion on the linked neutral variation that can be increased by AOD. Although this possibility has been recognized for a long time (Otha and Kimura 1969), it has been mainly considered an anecdotal process. Recently, both theoretical (Zhao and Charlesworth 2016) and genomic analyses (Gilbert et al. 2020) have renewed interest in such a process, suggesting that it could be important in weakly recombining regions of a genome. Donald Waller (2021) - one of the co-authors of the current work - also recently proposed that POD could be quantitatively important with broad implications, and could resolve some unexplained observations such as the maintenance of inbreeding depression in highly selfing species. Yet, a proper theoretical framework analysing the effect of inbreeding on POD was lacking. In this theoretical work, Diala Abu Awad and Donald Waller (2022) addressed this question through an elegant combination of analytical predictions and intensive multilocus simulations. They determined the conditions under which POD can be maintained and how long it could resist erosion by recombination, which removes the negative association between deleterious alleles (repulsion) at the core of the mechanism. They showed that under tight linkage, POD regions can persist for a long time and generate substantial segregating load and inbreeding depression, even under inbreeding, so opposing (for a while) to the purging effect. They also showed that background selection can affect the genomic structure of POD regions by rapidly erasing weak POD regions but maintaining strong POD regions (i.e with many tightly linked deleterious alleles). These results have several implications. They can explain the maintenance of inbreeding depression despite inbreeding (as anticipated by Waller 2021), which has implications for the evolution of mating systems. If POD can hardly emerge under high selfing, it can persist from an outcrossing ancestor long after the transition towards a higher selfing rate and could explain the maintenance of mixed mating systems(which is possible with true overdominance, see Uyenoyama and Waller 1991). The results also have implications for genomic analyses, pointing to regions of low or no recombination where POD could be maintained, generating both higher diversity and heterozygosity than expected and variance in fitness. As structural variations are likely widespread in genomes with possible effects on suppressing recombination (Mérot et al. 2020), POD regions should be checked more carefully in genomic analyses (see also Gilbert et al. 2020). Overall, this work should stimulate new theoretical and empirical studies, especially to assess how quantitatively strong and widespread POD can be. It also stresses the importance of properly considering genetic linkage genome-wide, and so the role of recombination landscapes in determining patterns of diversity and fitness effects. References

Awad DA, Waller D (2022) Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depression. bioRxiv, 2021.12.16.473022, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.473022 Gilbert KJ, Pouyet F, Excoffier L, Peischl S (2020) Transition from Background Selection to Associative Overdominance Promotes Diversity in Regions of Low Recombination. Current Biology, 30, 101-107.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.11.063 Mérot C, Oomen RA, Tigano A, Wellenreuther M (2020) A Roadmap for Understanding the Evolutionary Significance of Structural Genomic Variation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35, 561–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.03.002 Ohta T, Kimura M (1969) Linkage disequilibrium at steady state determined by random genetic drift and recurrent mutation. Genetics, 63, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/63.1.229 Uyenoyama MK, Waller DM (1991) Coevolution of self-fertilization and inbreeding depression II. Symmetric overdominance in viability. Theoretical Population Biology, 40, 47–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(91)90046-I Waller DM (2021) Addressing Darwin’s dilemma: Can pseudo-overdominance explain persistent inbreeding depression and load? Evolution, 75, 779–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.14189 Zhao L, Charlesworth B (2016) Resolving the Conflict Between Associative Overdominance and Background Selection. Genetics, 203, 1315–1334. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.116.188912 | Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depression | Diala Abu Awad, Donald Waller | <p style="text-align: justify;">Classical models that ignore linkage predict that deleterious recessive mutations should purge or fix within inbred populations, yet inbred populations often retain moderate to high segregating load. True overdomina... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Sylvain Glémin | 2022-01-04 12:15:35 | View | |

01 Sep 2021

Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail speciesJarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242Determinants of population genetic structure in co-occurring freshwater snailsRecommended by Trine Bilde and Matteo Fumagalli and Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Genetic diversity is a key aspect of biodiversity and has important implications for evolutionary potential and thereby the persistence of species. Improving our understanding of the factors that drive genetic structure within and between populations is, therefore, a long-standing goal in evolutionary biology. However, this is a major challenge, because of the complex interplay between genetic drift, migration, and extinction/colonization dynamics on the one hand, and the biology and ecology of species on the other hand (Romiguier et al. 2014, Ellegren and Galtier 2016, Charlesworth 2003). Jarne et al. (2021) studied whether environmental and demographic factors affect the population genetic structure of four species of hermaphroditic freshwater snails in a similar way, using comparative analyses of neutral genetic microsatellite markers. Specifically, they investigated microsatellite variability of Hygrophila in almost 280 sites in Guadeloupe, Lesser Antilles, as part of a long-term survey experiment (Lamy et al. 2013). They then modelled the influence of the mating system, local environmental characteristics and demographic factors on population genetic diversity. Consistent with theoretical predictions (Charlesworth 2003), they detected higher genetic variation in two outcrossing species than in two selfing species, emphasizing the importance of the mating system in maintaining genetic diversity. The study further identified an important role of site connectivity, through its influences on effective population size and extinction/colonisation events. Finally, the study detects an influence of interspecific interactions caused by an ongoing invasion by one of the studied species on genetic structure, highlighting the indirect effect of changes in community composition and demography on population genetics. Jarne et al. (2021) could address the extent to which genetic structure is determined by demographic and environmental factors in multiple species given the remarkable sampling available. Additionally, the study system is extremely suitable to address this hypothesis as species’ habitats are defined and delineated. Whilst the authors did attempt to test for across-species correlations, further investigations on this matter are required. Moreover, the effect of interactions between factors should be appropriately considered in any modelling between genetic structure and local environmental or demographic features. The findings in this study contribute to improving our understanding of factors influencing population genetic diversity, and highlights the complexity of interacting factors, therefore also emphasizing the challenges of drawing general implications, additionally hampered by the relatively limited number of species studied. Jarne et al. (2021) provide an excellent showcase of an empirical framework to test determinants of genetic structure in natural populations. As such, this study can be an example for further attempts of comparative analysis of genetic diversity. References Charlesworth, D. (2003) Effects of inbreeding on the genetic diversity of populations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358, 1051-1070. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2003.1296 Ellegren, H. and Galtier, N. (2016) Determinants of genetic diversity. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17, 422-433. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.58 Jarne, P., Lozano del Campo, A., Lamy, T., Chapuis, E., Dubart, M., Segard, A., Canard, E., Pointier, J.-P. and David, P. (2021) Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species. HAL, hal-03295242, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242 Lamy, T., Gimenez, O., Pointier, J. P., Jarne, P. and David, P. (2013). Metapopulation dynamics of species with cryptic life stages. The American Naturalist, 181, 479-491. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/669676 Romiguier, J., Gayral, P., Ballenghien, M. et al. (2014) Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature, 515, 261-263. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13685 | Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species | Jarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. | <p style="text-align: justify;">The distribution of neutral genetic variation in subdivided populations is driven by the interplay between genetic drift, migration, local extinction and colonization. The influence of environmental and demographic ... | Adaptation, Evolutionary Dynamics, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Trine Bilde | 2021-02-11 19:57:51 | View | ||

21 Nov 2018

Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infectionFrederic Bertels, Karin J Metzner, Roland R Regoes https://doi.org/10.1101/168260Is convergence an evidence for positive selection?Recommended by Guillaume Achaz based on reviews by Jeffrey Townsend and 1 anonymous reviewerThe preprint by Bertels et al. [1] reports an interesting application of the well-accepted idea that positively selected traits (here variants) can appear several times independently; think about the textbook examples of flight capacity. Hence, the authors assume that reciprocally convergence implies positive selection. The methodology becomes then, in principle, straightforward as one can simply count variants in independent datasets to detect convergent mutations. References [1] Bertels, F., Metzner, K. J., & Regoes R. R. (2018). Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infection. BioRxiv, 168260, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/168260 | Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infection | Frederic Bertels, Karin J Metzner, Roland R Regoes | <p>Convergent evolution describes the process of different populations acquiring similar phenotypes or genotypes. Complex organisms with large genomes only rarely and only under very strong selection converge to the same genotype. In contrast, ind... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Guillaume Achaz | 2017-07-26 08:39:17 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer