Latest recommendations

| Id | Title▲ | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

11 May 2023

Co-obligate symbioses have repeatedly evolved across aphids, but partner identity and nutritional contributions vary across lineagesAlejandro Manzano-Marín, Armelle Coeur d'acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, Emmanuelle Jousselin https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.28.505559Flexibility in Aphid Endosymbiosis: Dual Symbioses Have Evolved Anew at Least Six TimesRecommended by Olivier Tenaillon based on reviews by Alex C. C. Wilson and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this intriguing study (Manzano-Marín et al. 2022) by Alejandro Manzano-Marin and his colleagues, the association between aphids and their symbionts is investigated through meta-genomic analysis of new samples. These associations have been previously described as leading to fascinating genomic evolution in the symbiont (McCutcheon and Moran 2012). The bacterial genomes exhibit a significant reduction in size and the range of functions performed. They typically lose the ability to produce many metabolites or biobricks created by the host, and instead, streamline their metabolism by focusing on the amino acids that the host cannot produce. This level of co-evolution suggests a stable association between the two partners. However, the new data suggests a much more complex pattern as multiple independent acquisitions of co-symbionts are observed. Co-symbiont acquisition leads to a partition of the functions carried out on the bacterial side, with the new co-symbiont taking over some of the functions previously performed by Buchnera. In most cases, the new co-symbiont also brings the ability to produce B1 vitamin. Various facultative symbiotic taxa are recruited to be co-symbionts, with the frequency of acquisition related to the bacterial niche and lifestyle. REFERENCES Manzano-Marín, Alejandro, Armelle Coeur D’acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, and Emmanuelle Jousselin. 2023. “Co-Obligate Symbioses Have Repeatedly Evolved across Aphids, but Partner Identity and Nutritional Contributions Vary across Lineages.” bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.28.505559. McCutcheon, John P., and Nancy A. Moran. 2012. “Extreme Genome Reduction in Symbiotic Bacteria.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 10 (1): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2670. | Co-obligate symbioses have repeatedly evolved across aphids, but partner identity and nutritional contributions vary across lineages | Alejandro Manzano-Marín, Armelle Coeur d'acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, Emmanuelle Jousselin | <p style="text-align: justify;">Aphids are a large family of phloem-sap feeders. They typically rely on a single bacterial endosymbiont, <em>Buchnera aphidicola</em>, to supply them with essential nutrients lacking in their diet. This association ... |  | Genome Evolution, Other, Species interactions | Olivier Tenaillon | 2022-11-16 10:13:37 | View | |

16 Mar 2017

POSTPRINT

Correlated paternity measures mate monopolization and scales with the magnitude of sexual selectionDorken, ME and Perry LE 10.1111/jeb.13013Measurement of sexual selection in plants made easierRecommended by Emmanuelle Porcher and Mathilde DufaySexual selection occurs in flowering plants too. However it tends to be understudied in comparison to animal sexual selection, in part because the minuscule size and long dispersal distances of the individuals producing male gametes (pollen grains) seriously complicate the estimation of male siring success and thereby the measurement of sexual selection. Dorken and Perry [1] introduce a novel and clever approach to estimate sexual selection in plants, which bypasses the need for a direct quantification of absolute male mating success. This approach builds on the fact that the strength of sexual selection is directly related to the ability of individuals to monopolize mates [2]. In plants, mate monopolization can be assessed by examining the proportion of seeds produced by a given plant that are full-sibs, i.e. that share the same father. A nice feature of this proportion of full-sib seeds per maternal parent is it equals the coefficient of correlated paternity of Ritland [3], which can be readily obtained from the hundreds of plant mating system studies using genetic markers. A less desirable feature of the proportion of full sibs per maternal plant is that it is inversely related to population size, an effect that should be corrected for. The resulting index of mate monopolization is a simple product: (coefficient of correlated paternity)x(population size – 1). The authors test whether their index of mate monopolization is a good correlate of sexual selection, measured more traditionally as the selection differential on a trait influencing mating success, using a combination of theoretical and experimental approaches. Both approaches confirm that the two quantities are positively correlated, which suggests that the index of mate monopolization could be a convenient way to estimate the relative strength of sexual selection in flowering plants. These results call for further investigation, e.g. to verify that the effect of population size is well controlled for, or to assess the effects of non-random mating and inbreeding depression; however, this work paves the way for an expansion of sexual selection studies in flowering plants. References [1] Dorken ME and Perry LE. 2017. Correlated paternity measures mate monopolization and scales with the magnitude of sexual selection. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 30: 377-387 doi: 10.1111/jeb.13013 [2] Klug H, Heuschele J, Jennions M and Kokko H. 2010. The mismeasurement of sexual selection. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 23:447-462. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01921.x [3] Ritland K. 1989. Correlated matings in the partial selfer Mimulus guttatus. Evolution 43:848-859. doi: 10.2307/2409312 | Correlated paternity measures mate monopolization and scales with the magnitude of sexual selection | Dorken, ME and Perry LE | Indirect measures of sexual selection have been criticized because they can overestimate the magnitude of selection. In particular, they do not account for the degree to which mating opportunities can be monopolized by individuals of the sex that ... |  | Sexual Selection | Emmanuelle Porcher | 2017-03-13 23:22:26 | View | |

03 Jun 2018

Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive conceptThomas Lenormand, Noemie Harmand, Romain Gallet https://doi.org/10.1101/276675Let’s move beyond costs of resistance!Recommended by Inês Fragata and Claudia Bank based on reviews by Danna Gifford, Helen Alexander and 1 anonymous reviewerThe increase in the prevalence of (antibiotic) resistance has become a major global health concern and is an excellent example of the impact of real-time evolution on human society. This has led to a boom of studies that investigate the mechanisms and factors involved in the evolution of resistance, and to the spread of the concept of "costs of resistance". This concept refers to the relative fitness disadvantage of a drug-resistant genotype compared to a non-resistant reference genotype in the ancestral (untreated) environment. In their paper, Lenormand et al. [1] discuss the history of this concept and highlight its caveats and limitations. The authors address both practical and theoretical problems that arise from the simplistic view of "costly resistance" and argue that they can be prejudicial for antibiotic resistance studies. For a better understanding, they visualize their points of critique by means of Fisher's Geometric model. The authors give an interesting historical overview of how the concept arose and speculate that it emerged (during the 1980s) in an attempt by ecologists to spread awareness that fitness can be environment-dependent, and because of the concept's parallels to trade-offs in life-history evolution. They then identify several problems that arise from the concept, which, besides the conceptual misunderstandings that they can cause, are important to keep in mind when designing experimental studies. The authors highlight and explain the following points: Lenormand et al.'s paper [1] is a timely perspective piece in light of the ever-increasing efforts to understand and tackle resistance evolution [2]. Although some readers may shy away from the rather theoretical presentation of the different points of concern, it will be useful for both theoretical and empirical readers by illustrating the misconceptions that can arise from the concept of the cost of resistance. Ultimately, the main lesson to be learned from this paper may not be to ban the term "cost of resistance" from one's vocabulary, but rather to realize that the successful fight against drug resistance requires more differential information than the measurement of fitness effects in a drug-treated vs. non-treated environment in the lab [3-4]. Specifically, a better integration of the ecological aspects of drug resistance evolution and maintenance is needed [5], and we are far from a general understanding of how environmental factors interact and influence an organism's (absolute and relative) fitness and the effect of resistance mutations. References [1] Lenormand T, Harmand N, Gallet R. 2018. Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive concept. bioRxiv 276675, ver. 3 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/276675 | Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive concept | Thomas Lenormand, Noemie Harmand, Romain Gallet | <p>The cost of resistance, or the fitness effect of resistance mutation in absence of the drug, is a very widepsread concept in evolutionary genetics and beyond. It has represented an important addition to the simplistic view that resistance mutat... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Experimental Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Population Genetics / Genomics | Inês Fragata | 2018-03-09 02:22:07 | View | |

13 Sep 2019

Deceptive combined effects of short allele dominance and stuttering: an example with Ixodes scapularis, the main vector of Lyme disease in the U.S.A.Thierry De Meeûs, Cynthia T. Chan, John M. Ludwig, Jean I. Tsao, Jaymin Patel, Jigar Bhagatwala, and Lorenza Beati https://doi.org/10.1101/622373New curation method for microsatellite markers improves population genetics analysesRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by Eric Petit, Martin Husemann and 2 anonymous reviewersGenetic markers are used for in modern population genetics/genomics to uncover the past neutral and selective history of population and species. Besides Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) obtained from whole genome data, microsatellites (or Short Tandem Repeats, SSR) have been common markers of choice in numerous population genetics studies of non-model species with large sample sizes [1]. Microsatellites can be used to uncover and draw inference of the past population demography (e.g. expansion, decline, bottlenecks…), population split, population structure and gene flow, but also life history traits and modes of reproduction (e.g. [2,3]). These markers are widely used in conservation genetics [4] or to study parasites or disease vectors [5]. Microsatellites do show higher mutation rate than SNPs increasing, on the one hand, the statistical power to infer recent events (for example crop domestication, [2,3]), while, on the other hand, decreasing their statistical power over longer time scales due to homoplasy [6]. References [1] Jarne, P., and Lagoda, P. J. (1996). Microsatellites, from molecules to populations and back. Trends in ecology & evolution, 11(10), 424-429. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)10049-5 | Deceptive combined effects of short allele dominance and stuttering: an example with Ixodes scapularis, the main vector of Lyme disease in the U.S.A. | Thierry De Meeûs, Cynthia T. Chan, John M. Ludwig, Jean I. Tsao, Jaymin Patel, Jigar Bhagatwala, and Lorenza Beati | <p>Null alleles, short allele dominance (SAD), and stuttering increase the perceived relative inbreeding of individuals and subpopulations as measured by Wright’s FIS and FST. Ascertainment bias, due to such amplifying problems are usually caused ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Other, Population Genetics / Genomics | Aurelien Tellier | 2019-05-02 20:52:08 | View | |

24 Aug 2022

Density dependent environments can select for extremes of body sizeTim Coulson, Anja Felmy, Tomos Potter, Gioele Passoni, Robert A Montgomery, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Peter J Hudson, Joseph Travis, Ronald D Bassar, Shripad D Tuljapurkar, Dustin Marshall, Sonya M Clegg https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.17.480952A population biological modeling approach for life history and body size evolutionRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn based on reviews by Frédéric Guillaume and 2 anonymous reviewersBody size evolution is a central theme in evolutionary biology. Particularly the question of when and how smaller body sizes can evolve continues to interest evolutionary ecologists, because most life history models, and the empirical evidence, document that large body size is favoured by natural and sexual selection in most (even small) organisms and environments at most times. How, then, can such a large range of body size and life history syndromes evolve and coexist in nature? The paper by Coulson et al. lifts this question to the level of the population, a relatively novel approach using so-called integral projection (simulation) models (IPMs) (as opposed to individual-based or game theoretical models). As is well outlined by (anonymous) Reviewer 1, and following earlier papers spearheading this approach in other life history contexts, the authors use the well-known carrying capacity (K) of population biology as the ultimate fitness parameter to be maximized or optimized (rather than body size per se), to ultimately identify factors and conditions promoting the evolution of extreme body sizes in nature. They vary (individual or population) size-structured growth trajectories to observe age and size at maturity, surivorship and fecundity/fertility schedules upon evaluating K (see their Fig. 1). Importantly, trade-offs are introduced via density-dependence, either for adult reproduction or for juvenile survival, in two (of several conceivable) basic scenarios (see their Table 2). All other relevant standard life history variables (see their Table 1) are assumed density-independent, held constant or zero (as e.g. the heritability of body size). The authors obtain evidence for disruptive selection on body size in both scenarios, with small size and a fast life history evolving below a threshold size at maturity (at the lowest K) and large size and a slow life history beyond this threshold (see their Fig. 2). Which strategy wins ultimately depends on the fitness benefits of delaying sexual maturity (at larger size and longer lifespan) at the adult stage relative to the preceeding juvenile mortality costs, in agreement with classic life history theory (Roff 1992, Stearns 1992). The modeling approach can be altered and refined to be applied to other key life history parameters and environments. These results can ultimately explain the evolution of smaller body sizes from large body sizes, or vice versa, and their corresponding life history syndromes, depending on the precise environmental circumstances. All reviewers agreed that the approach taken is technically sound (as far as it could be evaluated), and that the results are interesting and worthy of publication. In a first round of reviews various clarifications of the manuscript were suggested by the reviewers. The new version was substantially changed by the authors in response, to the extent that it now is a quite different but much clearer paper with a clear message palatable for the general reader. The writing is now to the point, the paper's focus becomes clear in the Introduction, Methods & Results are much less technical, the Figures illustrative, and the descriptions and interpretations in the Discussion are easy to follow. In general any reader may of course question the choice and realism of the scenarios and underlying assumptions chosen by the authors for simplicity and clarity, for instance no heritability of body size and no cost of reproduction (other than mortality). But this is always the case in modeling work, and the authors acknowledge and in fact suggest concrete extensions and expansions of their approach in the Discussion. References Coulson T., Felmy A., Potter T., Passoni G., Montgomery R.A., Gaillard J.-M., Hudson P.J., Travis J., Bassar R.D., Tuljapurkar S., Marshall D.J., Clegg S.M. (2022) Density-dependent environments can select for extremes of body size. bioRxiv, 2022.02.17.480952, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.17.480952 | Density dependent environments can select for extremes of body size | Tim Coulson, Anja Felmy, Tomos Potter, Gioele Passoni, Robert A Montgomery, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Peter J Hudson, Joseph Travis, Ronald D Bassar, Shripad D Tuljapurkar, Dustin Marshall, Sonya M Clegg | <p>Body size variation is an enigma. We do not understand why species achieve the sizes they do, and this means we also do not understand the circumstances under which gigantism or dwarfism is selected. We develop size-structured integral projecti... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Life History | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2022-02-21 07:59:04 | View | |

12 Jul 2017

Despite reproductive interference, the net outcome of reproductive interactions among spider mite species is not necessarily costlySalomé H. Clemente, Inês Santos, Rita Ponce, Leonor R. Rodrigues, Susana A. M. Varela and Sara Magalhães 10.1101/113274The pros and cons of mating with strangersRecommended by Vincent Calcagno based on reviews by Joël Meunier and Michael D Greenfield

Interspecific matings are by definition rare events in nature, but when they occur they can be very important, and not only because they might condition gene flow between species. Even when such matings have no genetic consequence, for instance if they do not yield any fertile hybrid offspring, they can still have an impact on the population dynamics of the species involved [1]. Such atypical pairings between heterospecific partners are usually regarded as detrimental or undesired; as they interfere with the occurrence or success of intraspecific matings, they are expected to cause a decline in absolute fitness. References [1] Gröning J. & Hochkirch A. 2008. Reproductive interference between animal species. The Quarterly Review of Biology 83: 257-282. doi: 10.1086/590510 [2] Clemente SH, Santos I, Ponce AR, Rodrigues LR, Varela SAM & Magalhaes S. 2017 Despite reproductive interference, the net outcome of reproductive interactions among spider mite species is not necessarily costly. bioRxiv 113274, ver. 4 of the 30th of June 2017. doi: 10.1101/113274 | Despite reproductive interference, the net outcome of reproductive interactions among spider mite species is not necessarily costly | Salomé H. Clemente, Inês Santos, Rita Ponce, Leonor R. Rodrigues, Susana A. M. Varela and Sara Magalhães | Reproductive interference is considered a strong ecological force, potentially leading to species exclusion. This supposes that the net effect of reproductive interactions is strongly negative for one of the species involved. Testing this requires... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Vincent Calcagno | 2017-03-06 11:48:08 | View | |

14 Feb 2024

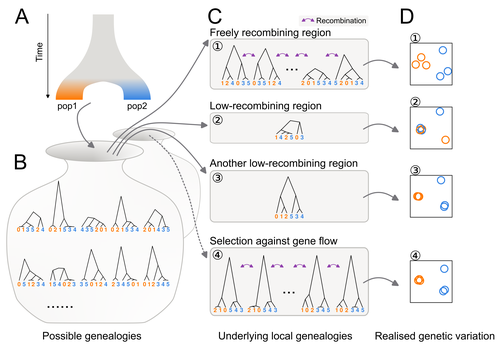

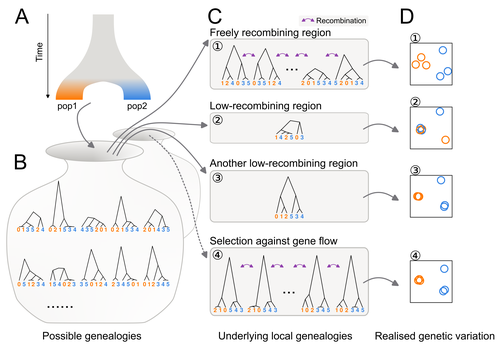

Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structureJun Ishigohoka, Karen Bascón-Cardozo, Andrea Bours, Janina Fuß, Arang Rhie, Jacquelyn Mountcastle, Bettina Haase, William Chow, Joanna Collins, Kerstin Howe, Marcela Uliano-Silva, Olivier Fedrigo, Erich D. Jarvis, Javier Pérez-Tris, Juan Carlos Illera, Miriam Liedvogel https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.22.473882Discerning the causes of local deviations in genetic variation: the effect of low-recombination regionsRecommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Claire Merot and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Claire Merot and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this study, Ishigohoka and colleagues tackle an important, yet often overlooked, question on the causes of genetic variation. While genome-wide patterns represent population structure, local variation is often associated with selection. Authors propose that an alternative cause for variation in individual loci is reduced recombination rate. To test this hypothesis, authors perform local Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (Li & Ralph, 2019) to identify local deviations in population structure in the Eurasian blackcap (Sylvia atricapilla) (Ishigohoka et al. 2022). This approach is typically used to detect chromosomal rearrangements or any long region of linked loci (e.g., due to reduced recombination or selection) (Mérot et al. 2021). While other studies investigated the effect of low recombination on genetic variation (Booker et al. 2020), here authors provide a comprehensive analysis of the effect of recombination to local PCA patterns both in empirical and simulated data sets. Findings demonstrate that low recombination (and not selection) can be the sole explanatory variable for outlier windows. The study also describes patterns of genetic variation along the genome of Eurasian blackcaps, localising at least two polymorphic inversions (Ishigohoka et al. 2022). Further investigations on the effect of model parameters (e.g., window sizes and thresholds for defining low-recombining regions), as well as the use of powerful neutrality tests are in need to clearly assess whether outlier regions experience selection and reduced recombination, and to what extent. References Booker, T. R., Yeaman, S., & Whitlock, M. C. (2020). Variation in recombination rate affects detection of outliers in genome scans under neutrality. Molecular Ecology, 29 (22), 4274–4279. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15501 Ishigohoka, J., Bascón-Cardozo, K., Bours, A., Fuß, J., Rhie, A., Mountcastle, J., Haase, B., Chow, W., Collins, J., Howe, K., Uliano-Silva, M., Fedrigo, O., Jarvis, E. D., Pérez-Tris, J., Illera, J. C., Liedvogel, M. (2022) Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structure. bioRxiv 2021.12.22.473882, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.22.473882 Li, H., & Ralph, P. (2019). Local PCA Shows How the Effect of Population Structure Differs Along the Genome. Genetics, 211 (1), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.118.301747 Mérot, C., Berdan, E. L., Cayuela, H., Djambazian, H., Ferchaud, A.-L., Laporte, M., Normandeau, E., Ragoussis, J., Wellenreuther, M., & Bernatchez, L. (2021). Locally Adaptive Inversions Modulate Genetic Variation at Different Geographic Scales in a Seaweed Fly. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 38 (9), 3953–3971. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab143 | Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structure | Jun Ishigohoka, Karen Bascón-Cardozo, Andrea Bours, Janina Fuß, Arang Rhie, Jacquelyn Mountcastle, Bettina Haase, William Chow, Joanna Collins, Kerstin Howe, Marcela Uliano-Silva, Olivier Fedrigo, Erich D. Jarvis, Javier Pérez-Tris, Juan Carlos Il... | <p>Genetic variation of the entire genome represents population structure, yet individual loci can show distinct patterns. Such deviations identified through genome scans have often been attributed to effects of selection instead of randomness. Th... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Matteo Fumagalli | 2023-10-13 11:58:47 | View | |

20 Nov 2019

Distribution of iridescent colours in hummingbird communities results from the interplay between selection for camouflage and communicationHugo Gruson, Marianne Elias, Juan L. Parra, Christine Andraud, Serge Berthier, Claire Doutrelant, Doris Gomez https://doi.org/10.1101/586362Feathers iridescence sheds light on the assembly rules of humingbirds communitiesRecommended by Sébastien Lavergne based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersEcology needs rules stipulating how species distributions and ecological communities should be assembled along environmental gradients, but few rules have yet emerged in the ecological literature. The search of ecogeographical rules governing the spatial variation of birds colours has recently known an upsurge of interest in the litterature [1]. Most studies have, however, looked at pigmentary colours and not structural colours (e.g. iridescence), although it is know that color perception by animals (both birds and their predators) can be strongly influenced by light diffraction causing iridescence patterns on feathers. References [1] Delhey, K. (2019). A review of Gloger’s rule, an ecogeographical rule of colour: definitions, interpretations and evidence. Biological Reviews, 94(4), 1294–1316. doi: 10.1111/brv.12503 | Distribution of iridescent colours in hummingbird communities results from the interplay between selection for camouflage and communication | Hugo Gruson, Marianne Elias, Juan L. Parra, Christine Andraud, Serge Berthier, Claire Doutrelant, Doris Gomez | <p>Identification errors between closely related, co-occurring, species may lead to misdirected social interactions such as costly interbreeding or misdirected aggression. This selects for divergence in traits involved in species identification am... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Sexual Selection, Species interactions | Sébastien Lavergne | 2019-03-29 17:23:20 | View | |

16 Nov 2022

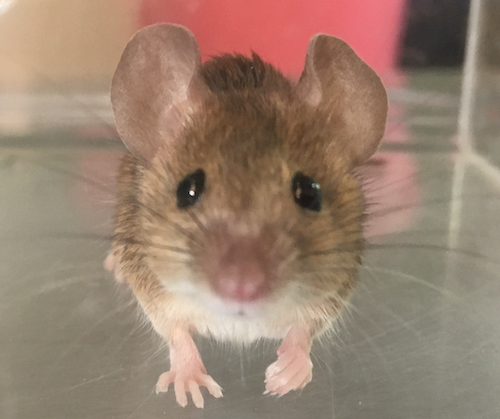

Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in miceCarole M. Smadja, Etienne Loire, Pierre Caminade, Dany Severac, Mathieu Gautier, Guila Ganem https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.21.500634Tinder in mice: A match made with the sense of smellRecommended by Christelle Fraïsse based on reviews by Angeles de Cara, Ludovic Claude Maisonneuve and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Angeles de Cara, Ludovic Claude Maisonneuve and 1 anonymous reviewer

Differentiation-based genome scans lie at the core of speciation and adaptation genomics research. Dating back to Lewontin & Krakauer (1973), they have become very popular with the advent of genomics to identify genome regions of enhanced differentiation relative to neutral expectations. These regions may represent genetic barriers between divergent lineages and are key for studying reproductive isolation. However, genome scan methods can generate a high rate of false positives, primarily if the neutral population structure is not accounted for (Bierne et al. 2013). Moreover, interpreting genome scans can be challenging in the context of secondary contacts between diverging lineages (Bierne et al. 2011), because the coupling between different components of reproductive isolation (local adaptation, intrinsic incompatibilities, mating preferences, etc.) can occur readily, thus preventing the causes of differentiation from being determined. Smadja and collaborators (2022) applied a sophisticated genome scan for trait association (BAYPASS, Gautier 2015) to underlie the genetic basis of a polygenetic behaviour: assortative mating in hybridizing mice. My interest in this neat study mainly relies on two reasons. First, the authors used an ingenious geographical setting (replicate pairs of “Choosy” versus “Non-Choosy” populations) with multi-way comparisons to narrow down the list of candidate regions resulting from BAYPASS. The latter corrects for population structure, handles cost-effective pool-seq data and allows for gene-based analyses that aggregate SNP signals within a gene. These features reinforce the set of outlier genes detected; however, not all are expected to be associated with mating preference. The second reason why this study is valuable to me is that Smadja et al. (2022) complemented the population genomic approach with functional predictions to validate the genetic signal. In line with previous behavioural and chemical assays on the proximal mechanisms of mating preferences, they identified multiple olfactory and vomeronasal receptor genes as highly significant candidates. Therefore, combining genomic signals with functional analyses is a clever way to provide insights into the causes of reproductive isolation, especially when multiple barriers are involved. This is typically true for reinforcement (Butlin & Smadja 2018), suspected to occur in these mice because, in that case, assortative mating (a prezygotic barrier) evolves in response to the cost of hybridization (for example, due to hybrid inviability). As advocated by the authors, their study paves the way for future work addressing the genetic basis of reinforcement, a trait of major evolutionary importance for which we lack empirical data. They also make a compelling case using complementary approaches that olfactory and vomeronasal receptors have a central role in mammal speciation.

Bierne N, Welch J, Loire E, Bonhomme F, David P (2011) The coupling hypothesis: why genome scans may fail to map local adaptation genes. Mol Ecol 20: 2044–2072. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05080.x Bierne N, Roze D, Welch JJ (2013) Pervasive selection or is it…? why are FST outliers sometimes so frequent? Mol Ecol 22: 2061–2064. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12241 Butlin RK, Smadja CM (2018) Coupling, Reinforcement, and Speciation. Am Nat 191:155–172. https://doi.org/10.1086/695136 Gautier M (2015) Genome-Wide Scan for Adaptive Divergence and Association with Population-Specific Covariates. Genetics 201:1555–1579. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.115.181453 Lewontin RC, Krakauer J (1973) Distribution of gene frequency as a test of the theory of selective neutrality of polymorphisms. Genetics 74: 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/74.1.175 Smadja CM, Loire E, Caminade P, Severac D, Gautier M, Ganem G (2022) Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in mice. bioRxiv, 2022.07.21.500634, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.21.500634 | Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in mice | Carole M. Smadja, Etienne Loire, Pierre Caminade, Dany Severac, Mathieu Gautier, Guila Ganem | <p>Deciphering the genetic bases of behavioural traits is essential to understanding how they evolve and contribute to adaptation and biological diversification, but it remains a substantial challenge, especially for behavioural traits with polyge... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Speciation | Christelle Fraïsse | 2022-07-25 11:54:52 | View | |

05 Oct 2022

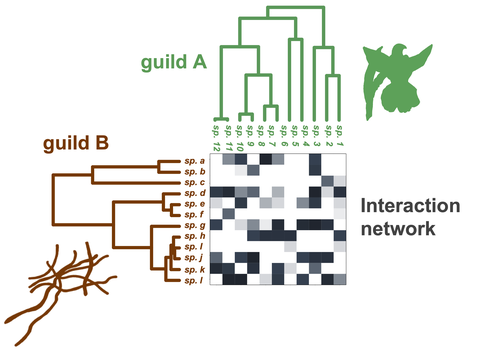

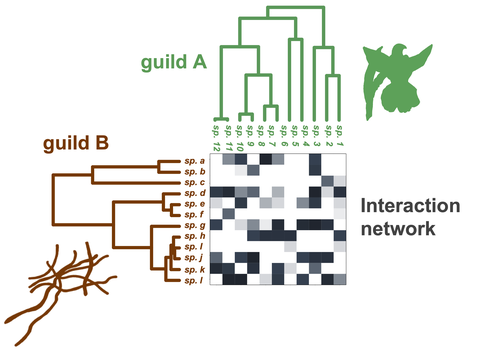

Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networksBenoît Perez-Lamarque, Odile Maliet, Benoît Pichon, Marc-André Selosse, Florent Martos, Hélène Morlon https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.30.458192Testing for phylogenetic signal in species interaction networksRecommended by Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer based on reviews by Joaquin Calatayud and Thomas GuillermeSpecies are immersed within communities in which they interact mutualistically, as in pollination or seed dispersal, or nonreciprocally, such as in predation or parasitism, with other species and these interactions play a paramount role in shaping biodiversity (Bascompte and Jordano 2013). Researchers have become increasingly interested in the processes that shape these interactions and how these influence community structure and responses to disturbances. Species interactions are often described using bipartite interaction networks and one important question is how the evolutionary history of the species involved influences the network, including whether there is phylogenetic signal in interactions, in other words whether closely related species interact with other closely related species (Bascompte and Jordano 2013, Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022). To address this question different approaches, correlative and model-based, have been developed to test for phylogenetic signal in interactions, although comparative analyses of the performance of these different metrics are lacking. In their article Perez-Lamarque et al. (2022) set out to test the statistical performance of two widely-used methods, Mantel tests and Phylogenetic Bipartite Linear Models (PBLM; Ives and Godfray 2006) using simulations. Phylogenetic signal is measured as the degree to which distance to the nearest common ancestor predicts the observed similarity in trait values among species. In species interaction networks, the data are actually the between-species dissimilarity among interacting species (Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022), and typical approaches to test for phylogenetic signal cannot be used. However, the Mantel test provides a useful means of analyzing the correlation between two distance matrices, the between-species phylogenetic distance and the between-species dissimilarity in interactions. The PBLM approach, on the other hand, assumes that interactions between species are influenced by unobserved traits that evolve along the phylogenies following a given phenotypic evolution model and the parameters of this model are interpreted in terms of phylogenetic signal (Ives and Godfray 2006). Perez-Lamarque et al (2022) found that the model-based PBLM approach has a high type-I error rate, in other words it often detected phylogenetic signal when there was none. The simple Mantel test was found to present a low type-I error rate and moderate statistical power. However, it tended to overestimate the degree to which species interact with dissimilar partners. In addition to the aforementioned analyses, the authors also tested whether the simple Mantel test was able to detect phylogenetic signal in interactions among species within a given clade in the phylogeny, as phylogenetic signal in species interactions may be localized within specific clades. The article concludes with general guidelines for users wishing to test phylogenetic signal in their interaction networks and illustrates them with an example of an orchid-mycorrhizal fungus network from the oceanic island of La Réunion (Martos et al 2012). This broadly accessible article provides a valuable analysis of the performance of tests of phylogenetic signal in interaction networks enabling users to make informed choices of the analytical methods they wish to employ, and provide useful and detailed guidelines. Therefore, the work should be of broad interest to researchers studying species interactions. References Bascompte J, Jordano P (2013) Mutualistic Networks. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400848720 Ives AR, Godfray HCJ (2006) Phylogenetic Analysis of Trophic Associations. The American Naturalist, 168, E1–E14. https://doi.org/10.1086/505157 Martos F, Munoz F, Pailler T, Kottke I, Gonneau C, Selosse M-A (2012) The role of epiphytism in architecture and evolutionary constraint within mycorrhizal networks of tropical orchids. Molecular Ecology, 21, 5098–5109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05692.x Perez-Lamarque B, Maliet O, Pichon B, Selosse M-A, Martos F, Morlon H (2022) Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks. bioRxiv, 2021.08.30.458192, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.30.458192 | Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks | Benoît Perez-Lamarque, Odile Maliet, Benoît Pichon, Marc-André Selosse, Florent Martos, Hélène Morlon | <p style="text-align: justify;">Whether interactions between species are conserved on evolutionary time-scales has spurred the development of both correlative and process-based approaches for testing phylogenetic signal in interspecific interactio... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer | 2022-03-10 13:48:15 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer