Latest recommendations

| Id | Title▲ | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

29 Nov 2023

Does sociality affect evolutionary speed?Lluís Socias-Martínez, Louise Rachel Peckre https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10086186On the evolutionary implications of being a social animalRecommended by Michael D Greenfield based on reviews by Rafael Lucas Rodriguez and 1 anonymous reviewerWhat does it mean to be highly social? Considering the so-called four ‘pinnacles’ of animal society (Wilson, 1975) – humans, cooperative breeding as found in some non-human mammals and birds, the social insects, and colonial marine invertebrates – having inter-individual relations extending beyond the sexual pair and the parent-offspring interaction is foremost. In many cases being social implies a high local population density, interaction with the same group of individuals over an extended time period, and an overlapping of generations. Additional features of social species may be a wide geographical range, perhaps associated with ecological and behavioral plasticity, the latter often facilitated by cultural transmission of traditions. Narrowing our perspective to the domain of PCI Evolutionary Biology, we might continue our question by asking whether being social predisposes one to a special evolutionary path toward the future. Do social species evolve faster (or slower) than their more solitary relatives such that over time they are more unlike (or similar to) those relatives (anagenesis)? And are evolutionary changes in social species more or less likely to be accompanied by lineage splitting (cladogenesis) and ultimately speciation? The latter question is parallel to one first posed over 40 years ago (West-Eberhard, 1979; Lande, 1981) for sexually selected traits: Do strong mating preferences and conspicuous courtship signals generate speciation via the Fisherian process or ecological divergence? An extensive survey of birds had found little supporting evidence (Price, 1998), but a recent one that focused on plumage complexity in tanagers did reveal a relationship, albeit a weak one (Price-Waldman et al., 2020). Because sexual selection has been viewed as a part of the broader process of social selection (West-Eberhard, 1979), it is thus fitting to extend our surveys to the evolutionary implications of being social. Unlike the inquiry for a sexual selection - evolutionary change connection, a social behavior counterpart has remained relatively untreated. Diverse logistical problems might account for this oversight. What objective proxies can be used for social behavior, and for the rate of evolutionary change within a lineage? How many empirical studies have generated data from which appropriate proxies could be extracted? More intractable is the conundrum arising from the connectedness between socially- and sexually-selected traits. For example, the elevated population density found in highly social species can greatly increase the mating advantage enjoyed by an attractive male. If anagenesis is detected, did it result from social behavior or sexual selection? And if social behavior leads to a group structure in which male-male competition is reduced, would a modest rate of evolutionary change be support for the sexual selection - evolutionary speed connection or evidence opposing the sociality - evolution one? Against the above odds, several biologists have begun to explore the notion that social behavior just might favor evolutionary speed in either anagenesis or cladogenesis. In a recent analysis relying on the comparative method, Lluís Socias-Martínez and Louise Rachel Peckre (2023) combed the scientific literature archives and identified those studies with specific data on the relationships between sexual selection or social behavior and evolutionary change, either anagenesis or cladogenesis. The authors were careful to employ fairly conservative criteria for including studies, and the number eventually retained was small. Nonetheless, some patterns emerge: Many more studies report anagenesis than cladogenesis, and many more report correlations with sexually-selected traits than with non-sexual social behavior ones. And, no study indicates a potential effect of social behavior on cladogenesis. Is this latter observation authentic or an artifact of a paucity of data? There are some a priori reasons why cladogenesis may seldom arise. Whereas highly social behavior could lead to fission encompassing mutually isolated population clusters within a species, social behavior may also engender counterbalancing plasticity that allows and even promotes inter-cluster migration and fusion. And briefly – and non-systematically, as the rate of lineage splitting would need to be measured – looking at one of the pinnacles of animal social behavior, the social insects, there is little indication that diversification has been accelerated. There are fewer than 3000 described species of termites, only ca. 16,000 ants, and the vast majority of bees and wasps are solitary. Lluís Socias-Martínez and Louise Rachel Peckre provide us with a very detailed discussion of these and a myriad of other complications. I end with a common refrain, we need more consideration of the authors’ interesting question, and much more data and analysis. One can thank Socias-Martínez and Peckre for pointing us in that direction. References Lande, R. (1981). Models of speciation by sexual selection on polygenic traits. Proc. Natn. Acad. Sci. USA 78, 3721-3725. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.78.6.3721 Price, T. (1998). Sexual selection and natural selection in bird speciation. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. B, 353, 251-260. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1998.0207 Price‐Waldman, R. M., Shultz, A. J., & Burns, K. J. (2020). Speciation rates are correlated with changes in plumage color complexity in the largest family of songbirds. Evolution, 74(6), 1155–1169. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13982 Socias-Martínez and Peckre. (2023). Does sociality affect evolutionary speed? Zenodo, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10086186 West-Eberhard, M. J. (1979). Sexual selection, social competition, and evolution. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 123(4), 222–234. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2828804 Wilson, E. O. (1975). Sociobiology. The New Synthesis. Cambridge, Mass., The Belknap Press of Harvard University | Does sociality affect evolutionary speed? | Lluís Socias-Martínez, Louise Rachel Peckre | <p>An overlooked source of variation in evolvability resides in the social lives of animals. In trying to foster research in this direction, we offer a critical review of previous work on the link between evolutionary speed and sociality. A first ... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Sexual Selection, Speciation | Michael D Greenfield | 2023-03-03 00:10:49 | View | |

05 Apr 2024

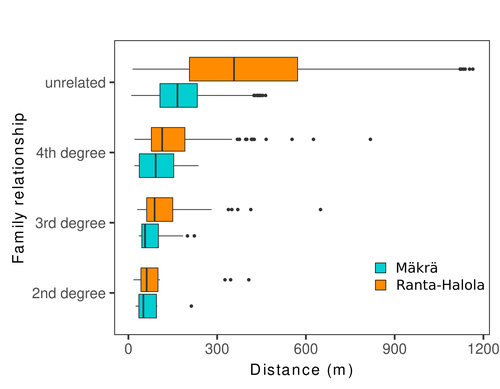

Does the seed fall far from the tree? Weak fine scale genetic structure in a continuous Scots pine populationAlina K. Niskanen, Sonja T. Kujala, Katri Kärkkäinen, Outi Savolainen, Tanja Pyhäjärvi https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.16.545344Weak spatial genetic structure in a large continuous Scots pine population – implications for conservation and breedingRecommended by Myriam Heuertz based on reviews by Joachim Mergeay, Jean-Baptiste Ledoux and Roberta Loh based on reviews by Joachim Mergeay, Jean-Baptiste Ledoux and Roberta Loh

Spatial genetic structure, i.e. the non-random spatial distribution of genotypes, arises in populations because of different processes including spatially limited dispersal and selection. Knowledge on the spatial genetic structure of plant populations is important to assess biological parameters such as gene dispersal distances and the potential for local adaptations, as well as for applications in conservation management and breeding. In their work, Niskanen and colleagues demonstrate a multifaceted approach to characterise the spatial genetic structure in two replicate sites of a continuously distributed Scots pine population in South-Eastern Finland. They mapped and assessed the ages of 469 naturally regenerated adults and genotyped them using a SNP array which resulted in 157 325 filtered polymorphic SNPs. Their dataset is remarkably powerful because of the large numbers of both individuals and SNPs genotyped. This made it possible to characterise precisely the decay of genetic relatedness between individuals with spatial distance despite the extensive dispersal capacity of Scots pine through pollen, and ensuing expectations of an almost panmictic population. The authors’ data analysis was particularly thorough. They demonstrated that two metrics of pairwise relatedness, the genomic relationship matrix (GRM, Yang et al. 2011) and the kinship coefficient (Loiselle et al. 1995) were strongly correlated and produced very similar inference of family relationships: >99% of pairs of individuals were unrelated, and the remainder exhibited 2nd (e.g., half-siblings) to 4th degree relatedness. Pairwise relatedness decayed with spatial distance which resulted in extremely weak but statistically significant spatial genetic structure in both sites, quantified as Sp=0.0005 and Sp=0.0008. These estimates are at least an order of magnitude lower than estimates in the literature obtained in more fragmented populations of the same species or in other conifers. Estimates of the neighbourhood size, the effective number of potentially mating individuals belonging to a within-population neighbourhood (Wright 1946), were relatively large with Nb=1680-3210 despite relatively short gene dispersal distances, σg = 36.5–71.3m, which illustrates the high effective density of the population. The authors showed the implications of their findings for selection. The capacity for local adaptation depends on dispersal distances and the strength of the selection coefficient. In the study population, the authors inferred that local adaptation can only occur if environmental heterogeneity occurs over a distance larger than approximately one kilometre (or larger, if considering long-distance dispersal). Interestingly, in Scots pine, no local adaptation has been described on similar geographic scales, in contrast to some other European or Mediterranean conifers (Scotti et al. 2023). The authors’ results are relevant for the management of conservation and breeding. They showed that related individuals occurred within sites only and that they shared a higher number of rare alleles than unrelated ones. Since rare alleles are enriched in new and recessive deleterious variants, selecting related individuals could have negative consequences in breeding programmes. The authors also showed, in their response to reviewers, that their powerful dataset was not suitable to obtain a robust estimate of effective population size, Ne, based on the linkage disequilibrium method (Do et al. 2014). This illustrated that the estimation of Ne used for genetic indicators supported in international conservation policy (Hoban et al. 2020, CBD 2022) remains challenging in large and continuous populations (see also Santo-del-Blanco et al. 2023, Gargiulo et al. 2024). ReferencesCBD (2022) Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf Do C, Waples RS, Peel D, Macbeth GM, Tillett BJ, Ovenden JR (2014). NeEstimator v2: re-implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne ) from genetic data. Molecular Ecology Resources 14: 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12157 Gargiulo R, Decroocq V, González-Martínez SC, Paz-Vinas I, Aury JM, Kupin IL, Plomion C, Schmitt S, Scotti I, Heuertz M (2024) Estimation of contemporary effective population size in plant populations: limitations of genomic datasets. Evolutionary Applications, in press, https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.18.549323 Hoban S, Bruford M, D’Urban Jackson J, Lopes-Fernandes M, Heuertz M, Hohenlohe PA, Paz-Vinas I, et al. (2020) Genetic diversity targets and indicators in the CBD post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework must be improved. Biological Conservation 248: 108654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108654 Loiselle BA, Sork VL, Nason J & Graham C (1995) Spatial genetic structure of a tropical understorey shrub, Psychotria officinalis (Rubiaceae). American Journal of Botany 82: 1420–1425. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1995.tb12679.x Santos-del-Blanco L, Olsson S, Budde KB, Grivet D, González-Martínez SC, Alía R, Robledo-Arnuncio JJ (2022). On the feasibility of estimating contemporary effective population size (Ne) for genetic conservation and monitoring of forest trees. Biological Conservation 273: 109704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109704 Scotti I, Lalagüe H, Oddou-Muratorio S, Scotti-Saintagne C, Ruiz Daniels R, Grivet D, et al. (2023) Common microgeographical selection patterns revealed in four European conifers. Molecular Ecology 32: 393-411. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16750 Wright S (1946) Isolation by distance under diverse systems of mating. Genetics 31: 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/31.1.39 Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME & Visscher PM (2011) GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. The American Journal of Human Genetics 88: 76–82. https://www.cell.com/ajhg/pdf/S0002-9297(10)00598-7.pdf | Does the seed fall far from the tree? Weak fine scale genetic structure in a continuous Scots pine population | Alina K. Niskanen, Sonja T. Kujala, Katri Kärkkäinen, Outi Savolainen, Tanja Pyhäjärvi | <p>Knowledge of fine-scale spatial genetic structure, i.e., the distribution of genetic diversity at short distances, is important in evolutionary research and in practical applications such as conservation and breeding programs. In trees, related... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Population Genetics / Genomics | Myriam Heuertz | Joachim Mergeay | 2023-06-27 21:57:28 | View |

24 Mar 2023

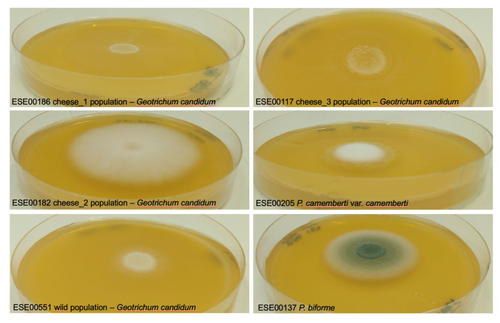

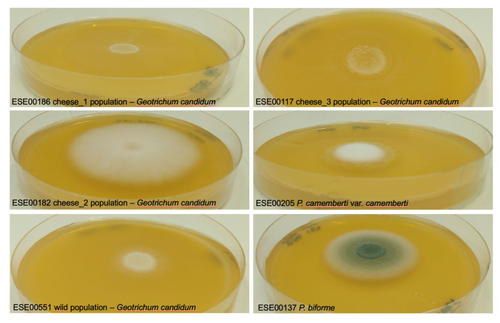

Domestication of different varieties in the cheese-making fungus Geotrichum candidumBastien Bennetot, Jean-Philippe Vernadet, Vincent Perkins, Sophie Hautefeuille, Ricardo C. Rodríguez de la Vega, Samuel O’Donnell, Alodie Snirc, Cécile Grondin, Marie-Hélène Lessard, Anne-Claire Peron, Steve Labrie, Sophie Landaud, Tatiana Giraud, Jeanne Ropars https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.17.492043Diverse outcomes in cheese fungi domesticationRecommended by Christelle Fraïsse based on reviews by Delphine Sicard and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Delphine Sicard and 1 anonymous reviewer

Domestication is a complex process that imprints the demography and the genomes of domesticated populations, enforcing strong selective pressures on traits favourable to humans, e.g. for food production [1]. Domestication has been quite intensely studied in plants and animals, but less so in micro-organisms such as fungi, despite their assets (e.g. their small genomes and tractability in the lab). This elegant study by Bennetot and collaborators [2] on the cheese-making fungus Geotrichum candidum adds to the mounting body of studies in the genomics of fungi, proving they are excellent models in evolutionary biology for studying adaptation and drift in eukaryotes [3]. Bennetot et al. newly showed with whole genome sequences that all G. candidum strains isolated from cheese form a monophyletic clade subdivided into three genetically differentiated populations with several admixed strains, while the wild strains sampled from diverse geographic locations form a sister clade. This suggests the wild progenitor was not sampled in the present study and calls for future exciting work on the domestication history of the G. candidum fungus. The authors scanned the genomes for footprints of adaptation to the cheese environment and identified promising candidates, such as a gene involved in iron uptake (this element is limiting in cheese). Their functional genome analysis also provides evidence for higher contents of transposable elements in cheese-making strains, likely due to relaxed selection during the domestication process. This paper is particularly impressive in that the authors complemented the population genomic approach with the phenotypic characterization of the strains and tested their ability to outcompete common fungal food spoilers. The authors convincingly showed that cheese-making strains display phenotypic differences relative to wild relatives for multiple traits such as slower growth, lower proteolysis activity and a greater amount of volatiles attractive to consumers, these phenotypes being beneficial for cheese making. Finally, this work is particularly inspiring because it thoroughly discusses convergent evolution during domestication in different cheese-associated fungi. Indeed, studying populations experiencing similar environmental pressures is fundamental to understanding whether evolution is repeatable [4]. For instance, all three cheese populations of G. candidum exhibit a lower genetic diversity than wild populations. However, only one population displays a stronger domestication syndrome, resembling the Penicillium camemberti situation [5]. Furthermore, different cheese-making practices may have led to varying situations with clonal lineages in non-Roquefort P. roqueforti and P. camemberti [5, 6], while the cheese-making G. candidum populations still harbour some diversity. In a nutshell, Bennetot's study makes an important contribution to evolutionary biology and highlights the value of diversifying our model organisms toward under-represented clades. REFERENCES [1] Diamond J (2002) Evolution, consequences and future of plant and animal domestication. Nature 418: 700–707. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01019 [2] Bennetot B, Vernadet J-P, Perkins V, Hautefeuille S, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, O’Donnell S, Snirc A, Grondin C, Lessard M-H, Peron A-C, Labrie S, Landaud S, Giraud T, Ropars J (2023) Domestication of different varieties in the cheese-making fungus Geotrichum candidum. bioRxiv, 2022.05.17.492043, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.17.492043 [3] Gladieux P, Ropars J, Badouin H, Branca A, Aguileta G, de Vienne DM, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Branco S, Giraud T (2014) Fungal evolutionary genomics provides insight into the mechanisms of adaptive divergence in eukaryotes. Mol. Ecol. 23: 753–773. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12631 [4] Bolnick DI, Barrett RD, Oke KB, Rennison DJ, Stuart YE (2018) (Non)Parallel evolution. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 49: 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110617-062240 [5] Ropars J, Didiot E, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Bennetot B, Coton M, Poirier E, Coton E, Snirc A, Le Prieur S, Giraud T (2020) Domestication of the Emblematic White Cheese-Making Fungus Penicillium camemberti and Its Diversification into Two Varieties. Current Biol. 30: 4441–4453.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.082 [6] Dumas, E, Feurtey, A, Rodríguez de la Vega, RC, Le Prieur S, Snirc A, Coton M, Thierry A, Coton E, Le Piver M, Roueyre D, Ropars J, Branca A, Giraud T (2020) Independent domestication events in the blue-cheese fungus Penicillium roqueforti. Mol Ecol. 29: 2639–2660. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15359 | Domestication of different varieties in the cheese-making fungus *Geotrichum candidum* | Bastien Bennetot, Jean-Philippe Vernadet, Vincent Perkins, Sophie Hautefeuille, Ricardo C. Rodríguez de la Vega, Samuel O’Donnell, Alodie Snirc, Cécile Grondin, Marie-Hélène Lessard, Anne-Claire Peron, Steve Labrie, Sophie Landaud, Tatiana Giraud,... | <p>Domestication is an excellent model for studying adaptation processes, involving recent adaptation and diversification, convergence following adaptation to similar conditions, as well as degeneration of unused functions. <em>Geotrichum candidum... |  | Adaptation, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Christelle Fraïsse | 2022-08-12 20:50:42 | View | |

25 Jan 2023

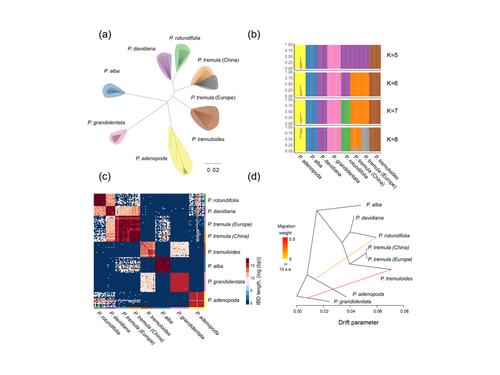

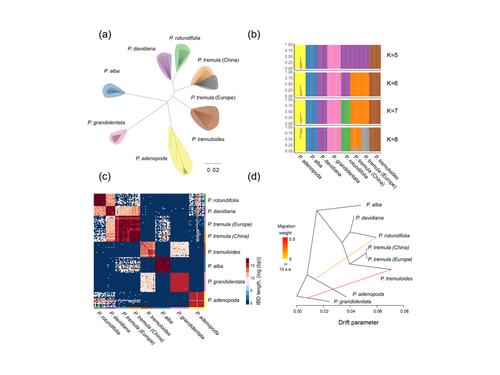

Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradientHuiying Shang, Martha Rendón-Anaya, Ovidiu Paun, View David L Field, Jaqueline Hess, Claus Vogl, Jianquan Liu, Pär K. Ingvarsson, Christian Lexer, Thibault Leroy https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.26.457771Shedding light on genomic divergence along the speciation continuumRecommended by Violaine Llaurens based on reviews by Camille Roux, Steven van Belleghem and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Camille Roux, Steven van Belleghem and 1 anonymous reviewer

The article “Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient” by Shang et al. describes an amazing dataset where genomic variations among 21 pairs of diverging poplar species are compared. Such comparisons are still quite rare and are needed to shed light on the processes shaping genomic divergence along the speciation gradient. Relying on two hundred whole-genome resequenced samples from 8 species that diverged from 1.3 to 4.8 million years ago, the authors aim at identifying the key factors involved in the genomic differentiation between species. They carried out a wide range of robust statistical tests aiming at characterizing the genomic differentiation along the genome of these species pairs. They highlight in particular the role of linked selection and gene flow in shaping the divergence along the genomes of species pairs. They also confirm the significance of introgression among species with a net divergence larger than the upper boundaries of the grey zone of speciation previously documented in animals (da from 0.005 to 0.02, Roux et al. 2016). Because these findings pave the way to research about the genomic mechanisms associated with speciation in species with allopatric and parapatric distributions, I warmingly recommend this article. References Roux C, Fraïsse C, Romiguier J, Anciaux Y, Galtier N, Bierne N (2016) Shedding Light on the Grey Zone of Speciation along a Continuum of Genomic Divergence. PLOS Biology, 14, e2000234. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2000234 Shang H, Rendón-Anaya M, Paun O, Field DL, Hess J, Vogl C, Liu J, Ingvarsson PK, Lexer C, Leroy T (2023) Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient. bioRxiv, 2021.08.26.457771, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.26.457771 | Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient | Huiying Shang, Martha Rendón-Anaya, Ovidiu Paun, View David L Field, Jaqueline Hess, Claus Vogl, Jianquan Liu, Pär K. Ingvarsson, Christian Lexer, Thibault Leroy | <p style="text-align: justify;">Speciation, the continuous process by which new species form, is often investigated by looking at the variation of nucleotide diversity and differentiation across the genome (hereafter genomic landscapes). A key cha... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Violaine Llaurens | 2021-09-06 14:12:27 | View | |

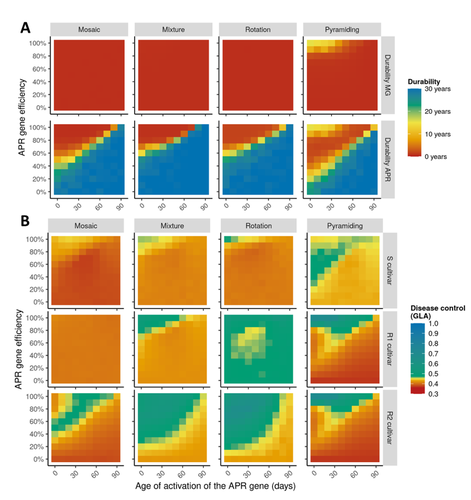

02 May 2023

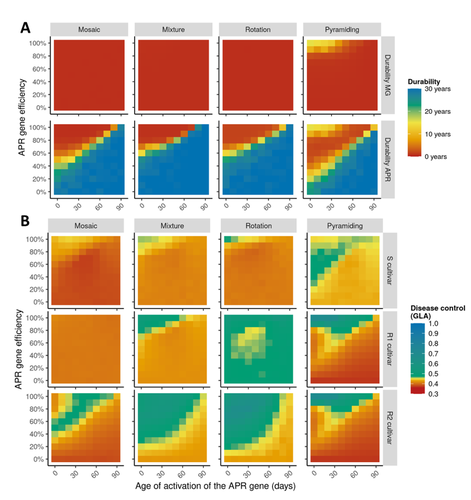

Durable resistance or efficient disease control? Adult Plant Resistance (APR) at the heart of the dilemmaLoup Rimbaud, Julien Papaïx, Jean-François Rey, Benoît Moury, Luke G. Barrett, Peter H. Thrall https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.30.505787Plant resistance to pathogens: just you wait?Recommended by Timothée Poisot based on reviews by Jean-Paul Soularue and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this preprint, Rimbaud et al. (2023) examine whether Adult Plant Resistance (APR), where plants delay their response to pathogens, is a viable alternative when the solution to evolve complete resistance from the seedling stage exists. At first glance, delaying resistance seems like a counter-intuitive strategy, unless it can result in a weaker selection of the pathogen, and therefore slow down its adaption to plant resistance. The approach of Rimbaud et al. is to incorporate as much of the mechanisms as possible into a model. By accounting for explicit spatio-temporal dynamics, stochasticity, and the coupling between demography and population genetics, to simulate an agricultural landscape, they reach a nuanced conclusion. Weaker and delayed activation of genes that confer APR does indeed reduce the selection pressure acting on the pathogen, at the cost of overall less effective protection. The alternative strategy of rapid or complete activation of these genes, although it results in better results in defending against the pathogen, is at risk of being overcome because it introduces a stronger selection pressure. One important feature of this work is that it accounts for agricultural practices. The landscape that is simulated can account for monoculture, mosaic cultures, mixed cultures, and rotations of crops (with different strategies for resistance). This introduces an interesting element to the conclusion: that human practices will have an impact on the selection pressures acting within the system. Perhaps the most striking result is that, for the plants, it might be more beneficial to bear the cost of a wild-type pathogen that can benefit from delayed activation of resistance, and therefore exclude the more virulent strains by simply being there first, and essentially buying the plant some time before it activates its resistance more completely. When the landscape is aggregated, even wild-type pathogens can cause severe epidemics; increasing fragmentation, because it enables connectivity between patches of plants with different strategies, allows pathogens to move across cultivars, and reduces the epidemic risk on susceptible plants. These results should encourage scaling up the perspective on APR, and indeed Rimbaud et al. adopt a landscape-scale perspective, to show that APR genes and genes conferring more complete resistance early on can have synergistic effects. This is, again, both an interesting result for evolutionary biologists, but also a useful way to prioritize different crop management strategies over large spatial scales. References Rimbaud, Loup, et al. Durable Resistance or Efficient Disease Control? Adult Plant Resistance (APR) at the Heart of the Dilemma. 2023. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.30.505787 | Durable resistance or efficient disease control? Adult Plant Resistance (APR) at the heart of the dilemma | Loup Rimbaud, Julien Papaïx, Jean-François Rey, Benoît Moury, Luke G. Barrett, Peter H. Thrall | <p style="text-align: justify;">Adult plant resistance (APR) is an incomplete and delayed protection of plants against pathogens. At first glance, such resistance should be less efficient than classical major-effect resistance genes, which confer ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Timothée Poisot | 2022-09-02 16:36:32 | View | |

08 Nov 2021

Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression over development in the stick insect Timema californicumJelisaveta Djordjevic, Zoé Dumas, Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Tanja Schwander, Darren James Parker https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.23.427895Sex-biased gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect: pattern during development, extent, functions involved, rate of sequence evolution, and comparison with an holometabolous insectRecommended by Nadia Aubin-Horth based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersAn individual’s sexual phenotype is determined during development. Understanding which pathways are activated or repressed during the developmental stages leading to a sexually mature individual, for example by studying gene expression and how its level is biased between sexes, allows us to understand the functional aspects of dimorphic phenotypes between the sexes. Several studies have quantified the differences in transcription between the sexes in mature individuals, showing the extent of this sex-bias and which functions are affected. There is, however, less data available on what occurs during the different phases of development leading to this phenotype, especially in species with specific developmental strategies, such as hemimetabolous insects. While many well-studied insects such as the honey bee, drosophila, and butterflies, exhibit an holometabolous development ("holo" meaning "complete" in reference to their drastic metamorphosis from the juvenile to the adult stage), hemimetabolous insects have juvenile stages that look similar to the adult stage (the hemi prefix meaning "half", referring to the more tissue-specific changes during development), as seen in crickets, cockroaches, and stick insects. Learning more about what happens during development in terms of the identity of genes that are sex-biased (are they the same genes at different developmental stages? What are their function? Do they exhibit specific sequence evolution rates? Is one sex over-represented in the sex-biased genes?) and their quantity over developmental time (gradual or abrupt increase in number, if any?) would allow us to better understand the evolution of sexual dimorphism at the gene expression level and how it relates to dimorphism at the organismic level. Djordjevic et al (2021) studied the transcriptome during development in an hemimetabolous stick insect, to improve our knowledge of this type of development, where the organismic phenotype is already mostly present in the early life stages. To do this, they quantified whole-genome gene expression levels in whole insects, using RNA-seq at three different developmental stages. One of the interesting results presented by Djordjevic and colleagues is that the increase in the number of genes that were sex-biased in expression is gradual over the three stages of development studied and it is mostly the same genes that stay sex-biased over time, reflecting the gradual change in phenotypes between hatchlings, juveniles and adults. Furthermore, male-biased genes had faster sequence divergence rates than unbiased genes and that female-biased genes. This new information of sex-bias in gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect allowed the authors to do a comparison of sex-biased genes with what has been found in a well-studied holometabolous insect, Drosophila. The gene expression patterns showed that four times more genes were sex-biased in expression in that species than in stick insects. Furthermore, the increase in the number of sex-biased genes during development was quite abrupt and clearly distinct in the adult stage, a pattern that was not seen in stick insects. As pointed out by the authors, this pattern of a "burst" of sex-biased genes at maturity is more common than the gradual increase seen in stick insects. With this study, we now know more about the evolution of sex-biased gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect and how it relates to their phenotypic dimorphism. Clearly, the next step will be to sample more hemimetabolous species at different life stages, to see how this pattern is widespread or not in this mode of development in insects. References Djordjevic J, Dumas Z, Robinson-Rechavi M, Schwander T, Parker DJ (2021) Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression during development in the stick insect Timema californicum. bioRxiv, 2021.01.23.427895, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.23.427895 | Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression over development in the stick insect Timema californicum | Jelisaveta Djordjevic, Zoé Dumas, Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Tanja Schwander, Darren James Parker | <p style="text-align: justify;">Sexually dimorphic phenotypes are thought to arise primarily from sex-biased gene expression during development. Major changes in developmental strategies, such as the shift from hemimetabolous to holometabolous dev... |  | Evo-Devo, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Nadia Aubin-Horth | 2021-04-22 17:36:32 | View | |

18 Aug 2020

Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemics in FranceGonché Danesh, Baptiste Elie,Yannis Michalakis, Mircea T. Sofonea, Antonin Bal, Sylvie Behillil, Grégory Destras, David Boutolleau, Sonia Burrel, Anne-Geneviève Marcelin, Jean-Christophe Plantier, Vincent Thibault, Etienne Simon-Loriere, Sylvie van der Werf, Bruno Lina, Laurence Josset, Vincent Enouf, Samuel Alizon and the COVID SMIT PSL group https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.03.20119925SARS-Cov-2 genome sequence analysis suggests rapid spread followed by epidemic slowdown in FranceRecommended by B. Jesse Shapiro based on reviews by Luca Ferretti and 2 anonymous reviewersSequencing and analyzing SARS-Cov-2 genomes in nearly real time has the potential to quickly confirm (and inform) our knowledge of, and response to, the current pandemic [1,2]. In this manuscript [3], Danesh and colleagues use the earliest set of available SARS-Cov-2 genome sequences available from France to make inferences about the timing of the major epidemic wave, the duration of infections, and the efficacy of lockdown measures. Their phylodynamic estimates -- based on fitting genomic data to molecular clock and transmission models -- are reassuringly close to estimates based on 'traditional' epidemiological methods: the French epidemic likely began in mid-January or early February 2020, and spread relatively rapidly (doubling every 3-5 days), with people remaining infectious for a median of 5 days [4,5]. These transmission parameters are broadly in line with estimates from China [6,7], but are currently unknown in France (in the absence of contact tracing data). By estimating the temporal reproductive number (Rt), the authors detected a slowing down of the epidemic in the most recent period of the study, after mid-March, supporting the efficacy of lockdown measures. References [1] Grubaugh, N. D., Ladner, J. T., Lemey, P., Pybus, O. G., Rambaut, A., Holmes, E. C., & Andersen, K. G. (2019). Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty-first century. Nature microbiology, 4(1), 10-19. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0296-2 | Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemics in France | Gonché Danesh, Baptiste Elie,Yannis Michalakis, Mircea T. Sofonea, Antonin Bal, Sylvie Behillil, Grégory Destras, David Boutolleau, Sonia Burrel, Anne-Geneviève Marcelin, Jean-Christophe Plantier, Vincent Thibault, Etienne Simon-Loriere, Sylvie va... | <p>France was one of the first countries to be reached by the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, we analyse 196 SARS-Cov-2 genomes collected between Jan 24 and Mar 24 2020, and perform a phylodynamics analysis. In particular, we analyse the doubling time, r... |  | Evolutionary Epidemiology, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | B. Jesse Shapiro | 2020-06-04 13:13:57 | View | |

20 Nov 2017

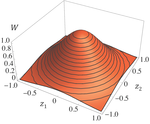

Effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance, mutation load and inbreeding depression under stabilizing selectionDiala Abu Awad and Denis Roze 10.1101/180000Understanding genetic variance, load, and inbreeding depression with selfingRecommended by Aneil F. Agrawal based on reviews by Frédéric Guillaume and 1 anonymous reviewerA classic problem in evolutionary biology is to understand the genetic variance in fitness. The simplest hypothesis is that variation exists, even in well-adapted populations, as a result of the balance between mutational input and selective elimination. This variation causes a reduction in mean fitness, known as the mutation load. Though mutation load is difficult to quantify empirically, indirect evidence of segregating genetic variation in fitness is often readily obtained by comparing the fitness of inbred and outbred offspring, i.e., by measuring inbreeding depression. Mutation-selection balance models have been studied as a means of understanding the genetic variance in fitness, mutation load, and inbreeding depression. Since their inception, such models have increased in sophistication, allowing us to ask these questions under more realistic and varied scenarios. The new theoretical work by Abu Awad and Roze [1] is a substantial step forward in understanding how arbitrary levels of self-fertilization affect variation, load and inbreeding depression under mutation-selection balance. References [1] Abu Awad D and Roze D. 2017. Effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance, mutation load and inbreeding depression under stabilizing selection. bioRxiv, 180000, ver. 4 of 17th November 2017. doi: 10.1101/180000 [2] Lande R. 1977. The influence of the mating system on the maintenance of genetic variability in polygenic characters. Genetics 86: 485–498. [3] Charlesworth D and Charlesworth B. 1987. Inbreeding depression and its evolutionary consequences. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 18: 237–268. doi: 10.1111/10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.001321 [4] Lande R and Porcher E. 2015. Maintenance of quantitative genetic variance under partial self-fertilization, with implications for the evolution of selfing. Genetics 200: 891–906. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.176693 [5] Roze D. 2015. Effects of interference between selected loci on the mutation load, inbreeding depression, and heterosis. Genetics 201: 745–757. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.178533 [6] Martin G and Lenormand T. 2006. A general multivariate extension of Fisher's geometrical model and the distribution of mutation fitness effects across species. Evolution 60: 893–907. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01169.x [7] Martin G, Elena SF and Lenormand T. 2007. Distributions of epistasis in microbes fit predictions from a fitness landscape model. Nature Genetics 39: 555–560. doi: 10.1038/ng1998 | Effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance, mutation load and inbreeding depression under stabilizing selection | Diala Abu Awad and Denis Roze | The mating system of a species is expected to have important effects on its genetic diversity. In this paper, we explore the effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance Vg, mutation load L and inbreeding depression δ under stabi... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Aneil F. Agrawal | 2017-08-26 09:29:20 | View | |

21 Nov 2019

Environmental specificity in Drosophila-bacteria symbiosis affects host developmental plasticityRobin Guilhot, Antoine Rombaut, Anne Xuéreb, Kate Howell, Simon Fellous https://doi.org/10.1101/717702Nutrition-dependent effects of gut bacteria on growth plasticity in Drosophila melanogasterRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewerIt is well known that the rearing environment has strong effects on life history and fitness traits of organisms. Microbes are part of every environment and as such likely contribute to such environmental effects. Gut bacteria are a special type of microbe that most animals harbor, and as such they are part of most animals’ environment. Such microbial symbionts therefore likely contribute to local adaptation [1]. The main question underlying the laboratory study by Guilhot et al. [2] was: How much do particular gut bacteria affect the organismal phenotype, in terms of life history and larval foraging traits, of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, a common laboratory model species in biology? References [1] Kawecki, T. J. and Ebert, D. (2004) Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecology Letters 7: 1225-1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00684.x | Environmental specificity in Drosophila-bacteria symbiosis affects host developmental plasticity | Robin Guilhot, Antoine Rombaut, Anne Xuéreb, Kate Howell, Simon Fellous | <p>Environmentally acquired microbial symbionts could contribute to host adaptation to local conditions like vertically transmitted symbionts do. This scenario necessitates symbionts to have different effects in different environments. We investig... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity, Species interactions | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2019-02-13 15:22:23 | View | |

13 Nov 2017

Epidemiological trade-off between intra- and interannual scales in the evolution of aggressiveness in a local plant pathogen populationFrederic Suffert, Henriette Goyeau, Ivan Sache, Florence Carpentier, Sandrine Gelisse, David Morais, Ghislain Delestre 10.1101/151068The pace of pathogens’ adaptation to their host plantsRecommended by Benoit Moury based on reviews by Benoit Moury and 1 anonymous reviewerBecause of their shorter generation times and larger census population sizes, pathogens are usually ahead in the evolutionary race with their hosts. The risks linked to pathogen adaptation are still exacerbated in agronomy, where plant and animal populations are not freely evolving but depend on breeders and growers, and are usually highly genetically homogeneous. As a consequence, the speed of pathogen adaptation is crucial for agriculture sustainability. Unraveling the time scale required for pathogens’ adaptation to their hosts would notably greatly improve our estimation of the risks of pathogen emergence, the efficiency of disease control strategies and the design of epidemiological surveillance schemes. However, the temporal scale of pathogen evolution has received much less attention than its spatial scale [1]. In their study of a wheat fungal disease, Suffert et al. [2] reached contrasting conclusions about the pathogen adaptation depending on the time scale (intra- or inter-annual) and on the host genotype (sympatric or allopatric) considered, questioning the experimental assessment of this important problem. Suffert et al. [2] sampled two pairs of Zymoseptoria tritici (the causal agent of septoria leaf blotch) sub-populations in a bread wheat field plot, representing (i) isolates collected at the beginning or at the end of an epidemic in a single growing season (2009-2010 intra-annual sampling scale) and (ii) isolates collected from plant debris at the end of growing seasons in 2009 and in 2015 (inter-annual sampling scale). Then, they measured in controlled conditions two aggressiveness traits of the isolates of these four Z. tritici sub-populations, the latent period and the lesion size on leaves, on two wheat cultivars. One of the cultivars was considered as "sympatric" because it was at the source of the studied isolates and was predominant in the growing area before the experiment, whereas the other cultivar was considered as "allopatric" since it replaced the previous one and became predominant in the growing area during the sampling period. On the sympatric host, at the intra-annual scale, they observed a marginally-significant decrease in latent period and a significant decrease of the between-isolate variance for this trait, which are consistent with a selection of pathogen variants with an enhanced aggressiveness. In contrast, at the inter-annual scale, no difference in the mean or variance of aggressiveness trait values was observed on the sympatric host, suggesting a lack of pathogen adaptation. They interpreted the contrast between observations at the two time scales as the consequence of a trade-off for the pathogen between a gain of aggressiveness after several generations of asexual reproduction at the intra-annual scale and a decrease of the probability to reproduce sexually and to be transmitted from one growing season to the next. Indeed, at the end of the growing season, the most aggressive isolates are located on the upper leaves of plants, where the pathogen density and hence probably also the probability to reproduce sexually, is lower. On the allopatric host, the conclusion about the pathogen stability at the inter-annual scale was somewhat different, since a significant increase in the mean lesion size was observed (isolates corresponding to the intra-annual scale were not checked on the allopatric host). This shows the possibility for the pathogen to evolve at the inter-annual scale, for a given aggressiveness trait and on a given host. In conclusion, Suffert et al.’s [2] study emphasizes the importance of the experimental design in terms of sampling time scale and host genotype choice to analyze the pathogen adaptation to its host plants. It provides also an interesting scenario, at the crossroad of the pathogen’s reproduction regime, niche partitioning and epidemiological processes, to interpret these contrasted results. Pathogen adaptation to plant cultivars with major-effect resistance genes is usually fast, including in the wheat-Z. tritici system [3]. Therefore, this study will be of great help for future studies on pathogen adaptation to plant partial resistance genes and on strategies of deployment of such resistance at the landscape scale. References [2] Suffert F, Goyeau H, Sache I, Carpentier F, Gelisse S, Morais D and Delestre G. 2017. Epidemiological trade-off between intra- and interannual scales in the evolution of aggressiveness in a local plant pathogen population. bioRxiv, 151068, ver. 3 of 12th November 2017. doi: 10.1101/151068 [3] Brown JKM, Chartrain L, Lasserre-Zuber P and Saintenac C. 2015. Genetics of resistance to Zymoseptoria tritici and applications to wheat breeding. Fungal Genetics and Biology, 79: 33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.04.017 | Epidemiological trade-off between intra- and interannual scales in the evolution of aggressiveness in a local plant pathogen population | Frederic Suffert, Henriette Goyeau, Ivan Sache, Florence Carpentier, Sandrine Gelisse, David Morais, Ghislain Delestre | The efficiency of plant resistance to fungal pathogen populations is expected to decrease over time, due to its evolution with an increase in the frequency of virulent or highly aggressive strains. This dynamics may differ depending on the scale i... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Benoit Moury | 2017-06-23 21:04:54 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer