Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▲ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

04 Mar 2024

Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.).Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Aurore Bontemps, Julie Gauzere, Etienne Klein https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538521Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.)Recommended by Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

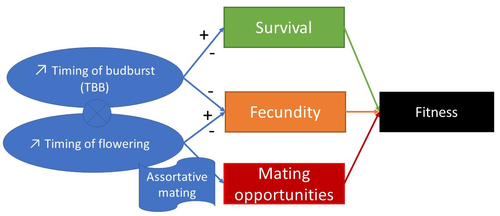

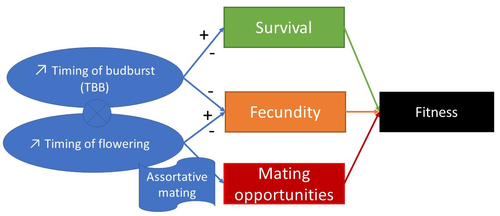

Starting with the seminar paper by Lande & Arnold (1983), several studies have addressed phenotypic selection in natural populations of a wide variety of organisms, with a recent renewed interest in forest trees (e.g., Oddou-Muratorio et al. 2018; Alexandre et al. 2020; Westergren et al. 2023). Because of their long generation times, long-lived organisms such as forest trees may suffer the most from maladaptation due to climate change, and whether they will be able to adapt to new environmental conditions in just one or a few generations is hotly debated. In this study, Oddou-Muratorio and colleagues (2024) extend the current framework to add two additional selection components that may alter patterns of fecundity selection and the estimation of standard selection gradients, namely sexual selection (evaluated as differences in flowering phenology conducting to assortative mating) and growth (viability) selection. Notably, the study is conducted in two contrasted environments (low vs high altitude populations) providing information on how the environment may modulate selection patterns in spring phenology. Spring phenology is a key adaptive trait that has been shown to be already affected by climate change in forest trees (Alberto et al. 2013). While fecundity selection for early phenology has been extensively reported before (see Munguía-Rosas et al. 2011), the authors found that this kind of selection can be strongly modulated by sexual selection, depending on the environment. Moreover, they found a significant correlation between early phenology and seedling growth in a common garden, highlighting the importance of this trait for early survival in European beech. As a conclusion, this original research puts in evidence the need for more integrative approaches for the study of natural selection in the field, as well as the importance of testing multiple environments and the relevance of common gardens to further evaluate phenotypic changes due to real-time selection. PS: The recommender and the first author of the preprint have shared authorship in a recent paper in a similar topic (Westergren et al. 2023). Nevertheless, the recommender has not contributed in any way or was aware of the content of the current preprint before acting as recommender, and steps have been taken for a fair and unpartial evaluation. References Alberto, F. J., Aitken, S. N., Alía, R., González‐Martínez, S. C., Hänninen, H., Kremer, A., Lefèvre, F., Lenormand, T., Yeaman, S., Whetten, R., & Savolainen, O. (2013). Potential for evolutionary responses to climate change - evidence from tree populations. Global Change Biology, 19(6), 1645‑1661. Oddou-Muratorio S, Bontemps A, Gauzere J, Klein E (2024) Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). bioRxiv, 2023.04.27.538521, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538521 Oddou-Muratorio, S., Gauzere, J., Bontemps, A., Rey, J.-F., & Klein, E. K. (2018). Tree, sex and size: Ecological determinants of male vs. female fecundity in three Fagus sylvatica stands. Molecular Ecology, 27(15), 3131‑3145. | Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (*Fagus sylvatica* L.). | Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Aurore Bontemps, Julie Gauzere, Etienne Klein | <p>Background: Plant phenological traits such as the timing of budburst or flowering can evolve on ecological timescales through response to fecundity and viability selection. However, interference with sexual selection may arise from assortative ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez | 2023-05-02 11:57:23 | View | |

05 Feb 2019

The quiescent X, the replicative Y and the AutosomesGuillaume Achaz, Serge Gangloff, Benoit Arcangioli https://doi.org/10.1101/351288Replication-independent mutations: a universal signature ?Recommended by Nicolas Galtier based on reviews by Marc Robinson-Rechavi and Robert LanfearMutations are the primary source of genetic variation, and there is an obvious interest in characterizing and understanding the processes by which they appear. One particularly important question is the relative abundance, and nature, of replication-dependent and replication-independent mutations - the former arise as cells replicate due to DNA polymerization errors, whereas the latter are unrelated to the cell cycle. A recent experimental study in fission yeast identified a signature of mutations in quiescent (=non-replicating) cells: the spectrum of such mutations is characterized by an enrichment in insertions and deletions (indels) compared to point mutations, and an enrichment of deletions compared to insertions [2]. References [1] Achaz, G., Gangloff, S., and Arcangioli, B. (2019). The quiescent X, the replicative Y and the Autosomes. BioRxiv, 351288, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/351288 | The quiescent X, the replicative Y and the Autosomes | Guillaume Achaz, Serge Gangloff, Benoit Arcangioli | <p>From the analysis of the mutation spectrum in the 2,504 sequenced human genomes from the 1000 genomes project (phase 3), we show that sexual chromosomes (X and Y) exhibit a different proportion of indel mutations than autosomes (A), ranking the... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Human Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Nicolas Galtier | 2018-07-25 10:37:48 | View | |

23 Jan 2020

A novel workflow to improve multi-locus genotyping of wildlife species: an experimental set-up with a known model systemGillingham, Mark A. F., Montero, B. Karina, Wilhelm, Kerstin, Grudzus, Kara, Sommer, Simone and Santos, Pablo S. C. https://doi.org/10.1101/638288Improving the reliability of genotyping of multigene families in non-model organismsRecommended by François Rousset based on reviews by Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins, Helena Westerdahl and Thomas BigotThe reliability of published scientific papers has been the topic of much recent discussion, notably in the biomedical sciences [1]. Although small sample size is regularly pointed as one of the culprits, big data can also be a concern. The advent of high-throughput sequencing, and the processing of sequence data by opaque bioinformatics workflows, mean that sequences with often high error rates are produced, and that exact but slow analyses are not feasible. References [1] Ioannidis, J. P. A, Greenland, S., Hlatky, M. A., Khoury, M. J., Macleod, M. R., Moher, D., Schulz, K. F. and Tibshirani, R. (2014) Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. The Lancet, 383, 166-175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62227-8 | A novel workflow to improve multi-locus genotyping of wildlife species: an experimental set-up with a known model system | Gillingham, Mark A. F., Montero, B. Karina, Wilhelm, Kerstin, Grudzus, Kara, Sommer, Simone and Santos, Pablo S. C. | <p>Genotyping novel complex multigene systems is particularly challenging in non-model organisms. Target primers frequently amplify simultaneously multiple loci leading to high PCR and sequencing artefacts such as chimeras and allele amplification... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | François Rousset | Helena Westerdahl, Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins, Paul J. McMurdie , Arnaud Estoup, Vincent Segura, Jacek Radwan , Torbjørn Rognes , William Stutz , Kevin Vanneste , Thomas Bigot, Jill A. Hollenbach , Wieslaw Babik , Marie-Christin... | 2019-05-15 17:30:44 | View |

26 Nov 2019

Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studiesJobran Chebib and Frédéric Guillaume https://doi.org/10.1101/656413Understanding the effects of linkage and pleiotropy on evolutionary adaptationRecommended by Kathleen Lotterhos based on reviews by Pär Ingvarsson and 1 anonymous reviewerGenetic correlations among traits are ubiquitous in nature. However, we still have a limited understanding of the genetic architecture of trait correlations. Some genetic correlations among traits arise because of pleiotropy - single mutations or genotypes that have effects on multiple traits. Other genetic correlations among traits arise because of linkage among mutations that have independent effects on different traits. Teasing apart the differential effects of pleiotropy and linkage on trait correlations is difficult, because they result in very similar genetic patterns. However, understanding these differential effects gives important insights into how ubiquitous pleiotropy may be in nature. References [1] Chebib, J. and Guillaume, F. (2019). Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studies. bioRxiv, 656413, v3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/656413 | Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studies | Jobran Chebib and Frédéric Guillaume | <p>Genetic correlations between traits may cause correlated responses to selection depending on the source of those genetic dependencies. Previous models described the conditions under which genetic correlations were expected to be maintained. Sel... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics | Kathleen Lotterhos | 2019-06-05 13:51:43 | View | |

06 May 2019

When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexualsFlorian Lavigne, Guillaume Martin, Yoann Anciaux, Julien Papaïx, Lionel Roques https://doi.org/10.1101/433235Fisher to the rescueRecommended by François Blanquart and Florence Débarre based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe ability of a population to adapt to a new niche is an important phenomenon in evolutionary biology. The colonisation of a new volcanic island by plant species; the colonisation of a host treated by antibiotics by a-resistant strain; the Ebola virus transmitting from bats to humans and spreading epidemically in Western Africa, are all examples of a population invading a new niche, adapting and eventually establishing in this new environment. Adaptation to a new niche can be studied using source-sink models. In the original environment —the “source”—, the population enjoys a positive growth-rate and is self-sustaining, while in the new environment —the “sink”— the population has a negative growth rate and is able to sustain only by the continuous influx of migrants from the source. Understanding the dynamics of adaptation to the sink environment is challenging from a theoretical standpoint, because it requires modelling the demography of the sink as well as the transient dynamics of adaptation. Moreover, local selection in the sink and immigration from the source create distributions of genotypes that complicate the use of many common mathematical approaches. In their paper, Lavigne et al. [1], develop a new deterministic model of adaptation to a harsh sink environment in an asexual species. The fitness of an individual is maximal when a number of phenotypes are tuned to an optimal value, and declines monotonously as phenotypes are further away from this optimum. This model —called Fisher’s Geometric Model— generates a GxE interaction for fitness because the phenotypic optimum in the sink environment is distinct from that in the source environment [2]. The authors circumvent mathematical difficulties by developing an original approach based on tracking the deterministic dynamics of the cumulant generating function of the fitness distribution in the sink. They derive a number of important results on the dynamics of adaptation to the sink:

In conclusion, this theoretical work presents a method based on Fisher’s Geometric Model and the use of cumulant generating functions to resolve some aspects of adaptation to a sink environment. It generates a number of theoretical predictions for the adaptive colonisation of a sink by an asexual species with some standing genetic variation. It will be a fascinating task to examine whether these predictions hold in experimental evolution systems: will we observe the four phases of the dynamics of mean fitness in the sink environment? Will the rate of adaptation indeed be independent of the immigration rate? Is there an optimal rate of mutation for adaptation to the sink? Such critical tests of the theory will greatly improve our understanding of adaptation to novel environments. References [1] Lavigne, F., Martin, G., Anciaux, Y., Papaïx, J., and Roques, L. (2019). When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexuals. bioRxiv, 433235, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/433235 | When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexuals | Florian Lavigne, Guillaume Martin, Yoann Anciaux, Julien Papaïx, Lionel Roques | <p>The successful establishment of a population into a new empty habitat outside of its initial niche is a phenomenon akin to evolutionary rescue in the presence of immigration. It underlies a wide range of processes, such as biological invasions ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology | François Blanquart | 2018-10-03 20:59:16 | View | |

07 Jul 2017

Unmasking the delusive appearance of negative frequency-dependent selectionRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by David Baltrus and 2 anonymous reviewersExplaining the processes that maintain polymorphisms in a population has been a fundamental line of research in evolutionary biology. One of the main mechanisms identified that preserves genetic diversity is negative frequency-dependent selection (NFDS), which constitutes a powerful framework for interpreting the presence of persistent polymorphisms. Nevertheless, a number of patterns that are often explained by invoking NFDS may also be compatible with, and possibly more easily explained by, different processes. References [1] Brisson D. 2017. Negative frequency-dependent selection is frequently confounding. bioRxiv 113324, ver. 3 of 20th June 2017. doi: 10.1101/113324 [2] Heino M, Metz JAJ and Kaitala V. 1998. The enigma of frequency-dependent selection. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 13: 367-370. doi: 1016/S0169-5347(98)01380-9 | Negative frequency-dependent selection is frequently confounding | Dustin Brisson | The existence of persistent genetic variation within natural populations presents an evolutionary problem as natural selection and genetic drift tend to erode genetic diversity. Models of balancing selection were developed to account for the high ... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Ignacio Bravo | 2017-03-03 18:46:42 | View | |

25 Sep 2023

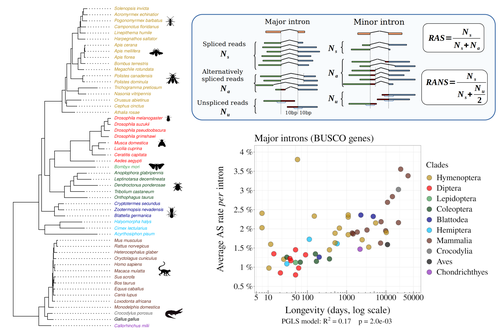

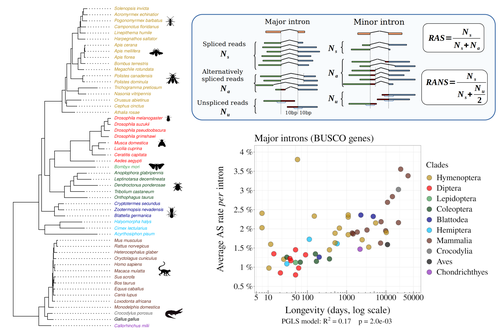

Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoansFlorian Benitiere, Anamaria Necsulea, Laurent Duret https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519597The drift barrier hypothesis and the limits to alternative splicing accuracyRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Lars M. Jakt and 2 anonymous reviewersAccurate information flow is central to living systems. The continuity of genomes through generations as well as the reproducible functioning and survival of the individual organisms require a faithful information transfer during replication, transcription and translation. The differential efficiency of natural selection against “mistakes” results in decreasing fidelity rates for replication, transcription and translation. At each level in the information flow chain (replication, transcription, translation), numerous complex molecular systems have evolved and been selected for preventing, identifying and, when possible, correcting or removing such “mistakes” arising during information transfer. However, fidelity cannot be improved ad infinitum. First, because of the limits imposed by the physical nature of the processes of copying and recoding information over different molecular supports: all mechanisms ensuring fidelity during biological information transfer ultimately rely on chemical kinetics and thermodynamics. The more accurate a copying process is, the lower the synthesis rate and the higher the energetic cost of correcting errors. Second, because of the limits imposed by random genetic drift: natural selection cannot effectively act on an allele that contributes with a small differential advantage unless effective population size is large. If s <1/Ne (or s <1/(2Ne) in diploids) the allele frequency in the population is de facto subject to neutral drift processes. In their preprint “Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans”, Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret explore the validity of this last mentioned “drift barrier” hypothesis for the case study of alternative splicing diversity in eukaryotes (Bénitière et al. 2022). Splicing refers to an ensemble of eukaryotic molecular processes mediated by a large number of proteins and ribonucleoproteins and involving nucleotide sequence recognition, that uses as a molecular substrate a precursor messenger RNA (mRNA), directly transcribed from the DNA, and produces a mature mRNA by removing introns and joining exons (Chow et al. 1977). Alternative splicing refers to the case in which different molecular species of mature mRNAs can be produced, either by cis-splicing processes acting on the same precursor mRNA, e.g. by varying the presence/absence of different exons or by varying the exon-exon boundaries, or by trans-splicing processes, joining exons from different precursor mRNA molecules. The diversity of mRNA molecular species generated by alternative splicing enlarges the molecular phenotypic space that can be generated from the same genotype. In humans, alternative splicing occurs in around 95% of the ca. 20,000 genes, resulting in ca. 100,000 medium-to-high abundance transcripts (Pan et al. 2008). In multicellular organisms, the frequency of alternatively spliced mRNAs varies between tissues and across ontogeny, often in a switch-like pattern (Wang et al. 2008). In the molecular and cell biology community, it is commonly accepted that splice variants contribute with specific functions (Marasco and Kornblihtt 2023) although there exists a discussion around the functional nature of low-frequency splice variants (see for instance the debate between Tress et al. 2017 and Blencowe 2017). The origin, diversity, regulation and evolutionary advantage of alternative splicing constitutes thus a playground of the selectionist-neutralist debate, with one extreme considering that most splice variants are mere “mistakes” of the splicing process (Pickrell et al. 2010), and the other extreme considering that alternative splicing is at the core of complexity in multicellular organisms, as it increases the genome coding potential and allows for a large repertoire of cell types (Chen et al. 2014). In their manuscript, Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret set the cursor towards the neutralist end of the gradient and test the hypothesis of whether the high alternative splice rate in “complex” organisms corresponds to a high rate of splicing “mistakes”, arising from the limit imposed by the drift barrier effect on the power of natural selection to increase accuracy (Bush et al. 2017). In their preprint, the authors convincingly show that in metazoans a fraction of the variation of alternative splicing rate is explained by variation in proxies of population size, so that species with smaller Ne display higher alternative splice rates. They communicate further that abundant splice variants tend to preserve the reading frame more often than low-frequency splice variants, and that the nucleotide splice signals in abundant splice variants display stronger evidence of purifying selection than those in low-frequency splice variants. From all the evidence presented in the manuscript, the authors interpret that “variation in alternative splicing rate is entirely driven by variation in the efficacy of selection against splicing errors”. The authors honestly present some of the limitations of the data used for the analyses, regarding i) the quality of the proxies used for Ne (i.e. body length, longevity and dN/dS ratio); ii) the heterogeneous nature of the RNA sequencing datasets (full organisms, organs or tissues; different life stages, sexes or conditions); and iii) mostly short RNA reads that do not fully span individual introns. Further, data from bacteria do not verify the herein communicated trends, as it has been shown that bacterial species with low population sizes do not display higher transcription error rates (Traverse and Ochman 2016). Finally, it will be extremely interesting to introduce a larger evolutionary perspective on alternative splicing rates encompassing unicellular eukaryotes, in which an intriguing interplay between alternative splicing and gene duplication has been communicated (Hurtig et al. 2020). The manuscript from Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret makes a significant advance to our understanding of the diversity, the origin and the physiology of post-transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms by emphasising the fundamental role of non-adaptive evolutionary processes and the upper limits to splicing accuracy set by genetic drift. References Bénitière F, Necsulea A, Duret L. 2023. Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519597 Blencowe BJ. 2017. The Relationship between Alternative Splicing and Proteomic Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci 42:407–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2017.04.001 Bush SJ, Chen L, Tovar-Corona JM, Urrutia AO. 2017. Alternative splicing and the evolution of phenotypic novelty. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 372:20150474. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0474 Chen L, Bush SJ, Tovar-Corona JM, Castillo-Morales A, Urrutia AO. 2014. Correcting for differential transcript coverage reveals a strong relationship between alternative splicing and organism complexity. Mol Biol Evol 31:1402–1413. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu083 Chow LT, Gelinas RE, Broker TR, Roberts RJ. 1977. An amazing sequence arrangement at the 5’ ends of adenovirus 2 messenger RNA. Cell 12:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(77)90180-5 Hurtig JE, Kim M, Orlando-Coronel LJ, Ewan J, Foreman M, Notice L-A, Steiger MA, van Hoof A. 2020. Origin, conservation, and loss of alternative splicing events that diversify the proteome in Saccharomycotina budding yeasts. RNA 26:1464–1480. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.075655.120 Marasco LE, Kornblihtt AR. 2023. The physiology of alternative splicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 24:242–254. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-022-00545-z Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. 2008. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet 40:1413–1415. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.259 Pickrell JK, Pai AA, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. 2010. Noisy splicing drives mRNA isoform diversity in human cells. PLoS Genet 6:e1001236. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001236 Traverse CC, Ochman H. 2016. Conserved rates and patterns of transcription errors across bacterial growth states and lifestyles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:3311–3316. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1525329113 Tress ML, Abascal F, Valencia A. 2017. Alternative Splicing May Not Be the Key to Proteome Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci 42:98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2016.08.008 Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP, Burge CB. 2008. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 456:470–476. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07509 | Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans | Florian Benitiere, Anamaria Necsulea, Laurent Duret | <p style="text-align: justify;">Most eukaryotic genes undergo alternative splicing (AS), but the overall functional significance of this process remains a controversial issue. It has been noticed that the complexity of organisms (assayed by the nu... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Ignacio Bravo | Anonymous | 2022-12-12 14:00:01 | View |

07 Nov 2019

New insights into the population genetics of partially clonal organisms: when seagrass data meet theoretical expectationsArnaud-Haond, Sophie, Stoeckel, Solenn, and Bailleul, Diane https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.10240v6Inferring rates of clonal versus sexual reproduction from population genetics dataRecommended by Olivier J Hardy based on reviews by Ludwig TRIEST, Stacy Krueger-Hadfield and 1 anonymous reviewerIn partially clonal organisms, genetic markers are often used to characterize the genotypic diversity of populations and infer thereof the relative importance of clonal versus sexual reproduction. Most studies report a measure of genotypic diversity based on a ratio, R, of the number of distinct multilocus genotypes over the sample size, and qualitatively interpret high / low R as indicating the prevalence of sexual / clonal reproduction. However, a theoretical framework allowing to quantify the relative rates of clonal versus sexual reproduction from genotypic diversity is still lacking, except using temporal sampling. Moreover, R is intrinsically highly dependent on sample size and sample design, while alternative measures of genotypic diversity are more robust to sample size, like D*, which is equivalent to the Gini-Simpson diversity index applied to multilocus genotypes. Another potential indicator of reproductive strategies is the inbreeding coefficient, Fis, because population genetics theory predicts that clonal reproduction should lead to negative Fis, at least when the sexual reproduction component occurs through random mating. Taking advantage of this prediction, Arnaud-Haond et al. [1] reanalysed genetic data from 165 populations of four partially clonal seagrass species sampled in a standardized way. They found positive correlations between Fis and both R and D* within each species, reflecting variation in the relative rates of sexual versus clonal reproduction among populations. Moreover, the differences of mean genotypic diversity and Fis values among species were also consistent with their known differences in reproductive strategies. Arnaud-Haond et al. [1] also conclude that previous works based on the interpretation of R generally lead to underestimate the prevalence of clonality in seagrasses. Arnaud-Haond et al. [1] confirm experimentally that Fis merits to be interpreted more properly than usually done when inferring rates of clonal reproduction from population genetics data of species reproducing both sexually and clonally. An advantage of Fis is that it is much less affected by sample size than R, and thus should be more reliable when comparing studies differing in sample design. Hence, when the rate of clonal reproduction becomes significant, we expect Fis < 0 and D* < 1. I expect these two indicators of clonality to be complementary because they rely on different consequences of clonality on pattern of genetic variation. Nevertheless, both measures can be affected by other factors. For example, null alleles, selfing or biparental inbreeding can pull Fis upwards, potentially eliminating the signature of clonal reproduction. Similarly, D* (and other measures of genotypic diversity) can be low because the polymorphism of the genetic markers used is too limited or because sexual reproduction often occurs through selfing, eventually resulting in highly similar homozygous genotypes. References [1] Arnaud-Haond, S., Stoeckel, S., and Bailleul, D. (2019). New insights into the population genetics of partially clonal organisms: when seagrass data meet theoretical expectations. ArXiv:1902.10240 [q-Bio], v6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1902.10240 | New insights into the population genetics of partially clonal organisms: when seagrass data meet theoretical expectations | Arnaud-Haond, Sophie, Stoeckel, Solenn, and Bailleul, Diane | <p>Seagrass meadows are among the most important coastal ecosystems, in terms of both spatial extent and ecosystem services, but they are also declining worldwide. Understanding the drivers of seagrass meadow dynamics is essential for designing so... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Olivier J Hardy | 2019-03-01 21:57:34 | View | |

18 Jan 2017

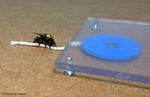

POSTPRINT

Associative Mechanisms Allow for Social Learning and Cultural Transmission of String Pulling in an InsectAlem S, Perry CJ, Zhu X, Loukola OJ, Ingraham T, Søvik E, Chittka L https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002564Culture in BumblebeesRecommended by Caroline Nieberding and Jacques J. M. van AlphenThis is an original paper [1] addressing the question whether cultural transmission occurs in insects and studying the mechanisms of such transmission. Often, culture-like phenomena require relatively sophisticated learning mechanisms, for example imitation and/or teaching. In insects, seemingly complex processes of social information acquisition, can sometimes instead be mediated by relatively simple learning mechanisms suggesting that cultural processes may not necessarily require sophisticated learning abilities. An important quality of this paper is to describe neatly the experimental protocols used for such typically complex behavioural analyses, providing a detailed understanding of the results while it remains a joy to read. This becomes rare in high impact journals. In a clever experimental design, individual bumblebees are trained to pull an artificial flower from under a Plexiglas table to get access to a reward, by pulling a string attached to the flower. Individuals that have learnt this task are then shown to inexperienced bees while performing this task. This results in a large proportion of the inexperienced observers learning to pull the string and getting access to the reward. Finally, the authors could then document the spread of the string pulling skill amongst other workers in the colony. Even when the originally trained individuals had died, the skill of string-pulling persisted in the colony, as long as they were challenged with the task. This shows that cultural transmission takes place within a colony. The authors provide evidence that the transmission of this behavior among individuals relies on a mix of social learning by local enhancement (bees were attracted to the location where they had observed a demonstrator) and of non-social, individual learning (pulling the string is learned by trial and errors and not by direct imitation of the conspecific). Data also show that simple associative mechanisms are enough and that stimulus enhancement was involved (bees were attracted to the string when its location was concordant with that during prior observation). The cleverly designed experiments use a paradigm (string-pulling) which has often been used to investigate cognitive abilities in vertebrates. Comparison with such studies indicate that bees, in some aspects of their learning, may not be different from birds, dogs, or apes as they also relied on the perceptual feedback provided by their actions, resulting in target movement to learn string pulling. The results of the study suggest that the combination of relatively simple forms of social learning and trial-and-error learning can mediate the acquisition of new skills and that bumblebees possess the essential cognitive elements for cultural transmission and in a broader sense, that the capacity of culture may be present within most animals. Can we expect behavioural innovation such as string pulling to occur in nature? Bombus terrestris colonies can reach a total of several hundreds foragers. In the experiments, foragers needed on average 5 rounds of observations with different demonstrators to learn how to pull the string. As individuals forage in a meadow full of flowers and conspecifics, transmission of behavioural innovations by repeated observations shouldn’t strike us as something impossible. Would the behavior survive through the winter? Bumblebee colonies are seasonal in northern areas and in the Mediterranean area but tropical species persists for several years. In seasonal species, all the workers die before winter and only new queens overwinter. So there is no possibility for seasonal foragers to transmit the technique overwinter. Only queens could potentially transmit it to new foragers in spring. However flowers are different in autumn and spring. Therefore, what queens have learnt about flowers in autumn would unlikely be useful in spring (providing that they can remember it). However there is no reason why the technique couldn't be transmitted from a colony to another between spring to autumn. Such transmission of new behaviour would more easily persist in perennial social insect colonies, like honeybees. Importantly, the bees used in these experiments came from a company whose rearing conditions are unknown, and only a few colonies were used for each experiment. As learning ability has a genetic basis [2-3], colonies differ in their ability to learn [4]. In this regard, the authors showed variation between individual bumblebees and between bumblebee colonies in learning ability. Hence, we would wish to know more about the level of genetic diversity in the wild, and of genetic differentiation between tested colonies (were they independent replicates?), to extrapolate the results to what may happen in the wild. Excitingly, the authors found 2 true innovators among the >400 individuals that were tested at least once for 5 min who would solve such a task without stepwise training or observation of skilled demonstrators, showing that behavioural innovation can occur in very small numbers of individuals, provided that an ecological trigger is provided (food reward). Hence this study shows that all ingredients for the long proposed “social heredity” theory proposed by Baldwin in 1896 are available in this organism, suggesting that social transmission of behavioural innovations could technically act as an additional mechanism for adaptive evolution [5], next to genetic evolution that may take longer to produce adaptive evolution. The question remains whether the behavioural innovations are arising from standing genetic variation in the bees, or do not need a firm genetic background to appear. References [1] Alem S, Perry CJ, Zhu X, Loukola OJ, Ingraham T, Søvik E, Chittka L. 2016. Associative mechanisms allow for social learning and cultural transmission of string pulling in an insect. PloS Biology 14:e1002564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002564 [2] Mery F, Kawecki TJ. 2002. Experimental evolution of learning ability in fruit flies. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 99:14274-14279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222371199 [3] Mery F, Belay AT, So AKC, Sokolowski MB, Kawecki TJ. 2007. Natural polymorphism affecting learning and memory in Drosophila. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 104:13051-13055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702923104 [4] Raine NE, Chittka L. 2008. The correlation of learning speed and natural foraging success in bumble-bees. Proceeding of the Royal Society of London 275: 803-808. doi : 10.1098/rspb.2007.1652 [5] Baldwin JM. 1896. A New Factor in Evolution. American Naturalist 30:441-451 and 536-553. doi: 10.1086/276408 | Associative Mechanisms Allow for Social Learning and Cultural Transmission of String Pulling in an Insect | Alem S, Perry CJ, Zhu X, Loukola OJ, Ingraham T, Søvik E, Chittka L | Social insects make elaborate use of simple mechanisms to achieve seemingly complex behavior and may thus provide a unique resource to discover the basic cognitive elements required for culture, i.e., group-specific behaviors that spread from “inn... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Non Genetic Inheritance, Phenotypic Plasticity | Caroline Nieberding | 2017-01-18 10:49:03 | View | |

13 Nov 2017

Epidemiological trade-off between intra- and interannual scales in the evolution of aggressiveness in a local plant pathogen populationFrederic Suffert, Henriette Goyeau, Ivan Sache, Florence Carpentier, Sandrine Gelisse, David Morais, Ghislain Delestre 10.1101/151068The pace of pathogens’ adaptation to their host plantsRecommended by Benoit Moury based on reviews by Benoit Moury and 1 anonymous reviewerBecause of their shorter generation times and larger census population sizes, pathogens are usually ahead in the evolutionary race with their hosts. The risks linked to pathogen adaptation are still exacerbated in agronomy, where plant and animal populations are not freely evolving but depend on breeders and growers, and are usually highly genetically homogeneous. As a consequence, the speed of pathogen adaptation is crucial for agriculture sustainability. Unraveling the time scale required for pathogens’ adaptation to their hosts would notably greatly improve our estimation of the risks of pathogen emergence, the efficiency of disease control strategies and the design of epidemiological surveillance schemes. However, the temporal scale of pathogen evolution has received much less attention than its spatial scale [1]. In their study of a wheat fungal disease, Suffert et al. [2] reached contrasting conclusions about the pathogen adaptation depending on the time scale (intra- or inter-annual) and on the host genotype (sympatric or allopatric) considered, questioning the experimental assessment of this important problem. Suffert et al. [2] sampled two pairs of Zymoseptoria tritici (the causal agent of septoria leaf blotch) sub-populations in a bread wheat field plot, representing (i) isolates collected at the beginning or at the end of an epidemic in a single growing season (2009-2010 intra-annual sampling scale) and (ii) isolates collected from plant debris at the end of growing seasons in 2009 and in 2015 (inter-annual sampling scale). Then, they measured in controlled conditions two aggressiveness traits of the isolates of these four Z. tritici sub-populations, the latent period and the lesion size on leaves, on two wheat cultivars. One of the cultivars was considered as "sympatric" because it was at the source of the studied isolates and was predominant in the growing area before the experiment, whereas the other cultivar was considered as "allopatric" since it replaced the previous one and became predominant in the growing area during the sampling period. On the sympatric host, at the intra-annual scale, they observed a marginally-significant decrease in latent period and a significant decrease of the between-isolate variance for this trait, which are consistent with a selection of pathogen variants with an enhanced aggressiveness. In contrast, at the inter-annual scale, no difference in the mean or variance of aggressiveness trait values was observed on the sympatric host, suggesting a lack of pathogen adaptation. They interpreted the contrast between observations at the two time scales as the consequence of a trade-off for the pathogen between a gain of aggressiveness after several generations of asexual reproduction at the intra-annual scale and a decrease of the probability to reproduce sexually and to be transmitted from one growing season to the next. Indeed, at the end of the growing season, the most aggressive isolates are located on the upper leaves of plants, where the pathogen density and hence probably also the probability to reproduce sexually, is lower. On the allopatric host, the conclusion about the pathogen stability at the inter-annual scale was somewhat different, since a significant increase in the mean lesion size was observed (isolates corresponding to the intra-annual scale were not checked on the allopatric host). This shows the possibility for the pathogen to evolve at the inter-annual scale, for a given aggressiveness trait and on a given host. In conclusion, Suffert et al.’s [2] study emphasizes the importance of the experimental design in terms of sampling time scale and host genotype choice to analyze the pathogen adaptation to its host plants. It provides also an interesting scenario, at the crossroad of the pathogen’s reproduction regime, niche partitioning and epidemiological processes, to interpret these contrasted results. Pathogen adaptation to plant cultivars with major-effect resistance genes is usually fast, including in the wheat-Z. tritici system [3]. Therefore, this study will be of great help for future studies on pathogen adaptation to plant partial resistance genes and on strategies of deployment of such resistance at the landscape scale. References [2] Suffert F, Goyeau H, Sache I, Carpentier F, Gelisse S, Morais D and Delestre G. 2017. Epidemiological trade-off between intra- and interannual scales in the evolution of aggressiveness in a local plant pathogen population. bioRxiv, 151068, ver. 3 of 12th November 2017. doi: 10.1101/151068 [3] Brown JKM, Chartrain L, Lasserre-Zuber P and Saintenac C. 2015. Genetics of resistance to Zymoseptoria tritici and applications to wheat breeding. Fungal Genetics and Biology, 79: 33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.04.017 | Epidemiological trade-off between intra- and interannual scales in the evolution of aggressiveness in a local plant pathogen population | Frederic Suffert, Henriette Goyeau, Ivan Sache, Florence Carpentier, Sandrine Gelisse, David Morais, Ghislain Delestre | The efficiency of plant resistance to fungal pathogen populations is expected to decrease over time, due to its evolution with an increase in the frequency of virulent or highly aggressive strains. This dynamics may differ depending on the scale i... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Benoit Moury | 2017-06-23 21:04:54 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer