WURM Yannick

- http://wurmlab.com, Queen Mary University of London, London, United Kingdom

- Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Theory, Expression Studies, Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Hybridization / Introgression, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection, Species interactions

- recommender

Recommendations: 0

Review: 1

Review: 1

The insertion of a mitochondrial selfish element into the nuclear genome and its consequences

Some evolutionary insights into an accidental homing endonuclease passage from mitochondria to the nucleus

Recommended by Sylvain Charlat based on reviews by Jan Engelstaedter and Yannick WurmNot all genetic elements composing genomes are there for the benefit of their carrier. Many have no consequences on fitness, or too mild ones to be eliminated by selection, and thus stem from neutral processes. Many others are indeed the product of selection, but one acting at a different level, increasing the fitness of some elements of the genome only, at the expense of the “organism” as a whole. These can be called selfish genetic elements, and come into a wide variety of flavours [1], illustrating many possible means to cheat with “fair” reproductive processes such as meiosis, and thus get overrepresented in the offspring of their hosts. Producing copies of itself through transposition is one such strategy; a very successful one indeed, explaining a large part of the genomic content of many organisms. Killing non carrier gametes following meiosis in heterozygous carriers is another one. Less know and less common is the ability of some elements to turn heterozygous carriers into homozygous ones, that will thus transmit the selfish elements to all offspring instead of half. This is achieved by nucleic sequences encoding so-called “Homing endonucleases” (HEs). These proteins tend to induce double strand breaks of DNA specifically in regions homologous to their own insertion sites. The recombination machinery is such that the intact homologous region, that is, the one carrying the HE sequence, is then used as a template for the reparation of the break, resulting in the effective conversion of a non-carrier allele into a carrier allele. Such elements can also occur in the mitochondrial genomes of organisms where mitochondria are not strictly transmitted by one parent only, offering mitochondrial HEs some opportunities for “homing” into new non carrier genomes. This is the case in yeasts, where HEs were first reported [2,3].

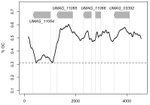

In this new study, based on genomic experimental data from the fungal maize pathogen Ustilago maydis, Julien Dutheil and colleagues [4] document one possible evolutionary pathway for which little evidence existed before: the passage of a mitochondrial HE into the nuclear genome. The GC content of this region leaves little doubt on its mitochondrial origin, and homologs can indeed be found in the mitochondrial genomes of close relatives. Strangely enough, U. maydis itself does not appear to carry this selfish element in its own mitochondria, suggesting it may have been acquired from a different species, or be subject to a sufficiently rapid turnover to have been recently lost.

Many elements of the story uncovered by this study remain mysterious. How, in the first place, was this HE gene inserted in a nuclear genomic region that shows no apparent homology with its original insertion site, making typical “homing” a not-so-likely explanation? This question may in fact be generalised to many HE systems: is the first insertion into a homing site always the product of a typical homing event, which implies the presence of an homologous template DNA fragment, or can HE genes insert through other means? But then, why specifically in regions that would be targeted by the nuclease they encode? What is the evolutionary fate of this newly inserted element? The new gene may well be on its way to pseudogenisation, as suggested by the truncation of its upper part, precluding its functioning as a HE, and the lack of evidence of selective constraints through dN/dS analysis; but the mutation generated by the insertion event may have phenotypic implications, possibly through the partial truncation of another gene, encoding a helicase. How old is this insertion? The fact that it has accumulated some mutations makes a very recent event rather unlikely, but this insertion has been detected in only one isolate of U. maydis, suggesting it is not so frequent in natural populations.

Whatever the answers to these open questions, that will hopefully be addressed by further work on this system, the present study has revealed that horizontal transmission enlarges the scope of possible evolutionary consequences of HE genes, that may move not only between mitochondrial genomes, but also occasionally into a nucleus.

References

[1] Burt, A., and Trivers, R. (2006). Genes in Conflict: The Biology of Selfish Genetic Elements. Belknap Press.

[2] Coen, D., Deutch, J., Netter, P., Petrochillo, E., and Slonimski, P. (1970). Mitochondrial genetics. I. Methodology and phenomenology. Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology, 24, 449-496.

[3] Colleaux, L., D’Auriol, L., Betermier, M., Cottarel, G., Jacquier, A., Galibert, F., and Dujon, B. (1986). Universal code equivalent of a yeast mitochondrial intron reading frame is expressed into E. coli as a specific double strand endonuclease. Cell, 44, 521–533. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90262-X

[4] Dutheil, J. Y., Münch, K., Schotanus, K., Stukenbrock, E. H., and Kahmann, R. (2020). The insertion of a mitochondrial selfish element into the nuclear genome and its consequences. bioRxiv, 787044, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/787044