SHYKOFF Jacqui A.

- Ecologie, Systétmatique et Evolution, CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette, France

- Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Life History, Sexual Selection, Species interactions

- recommender

Recommendation: 1

Reviews: 0

Recommendation: 1

Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesis

Evolutionary or proximal explanations for human male homosexual mate preference?

Recommended by Jacqui A. Shykoff based on reviews by Ray Blanchard and 1 anonymous reviewerNatural populations do not consist of only perfectly adapted individuals. If they did, of course, there would be no fodder for evolution by natural selection. And natural selection is operating all the time, winnowing out less well adapted phenotypes through differential reproduction and survival. Demonstrations of natural selection modifying characters-state distributions to bring phenotypes closer to their optima abound in the evolution literature, with examples of short- and long-term changes in phenotype and allele frequencies.

However, evolutionary biologists know that populations cannot reach their adaptive peaks. Natural selection is tracking a moving target, always with some generations of lag time. The adaptive landscape is multidimensional, so the optimal combination of multiple character states may be impossible because of constraints and trade-offs. Natural selection does not operate alone or in isolation – new mutations and migrants that were selected under other conditions will inject locally non-adaptive genetic variation and genetic drift can change allele frequencies in random directions. We understand these processes that generate and maintain less advantageous variants on a continuous gradient from an optimal phenotype in a fitness landscape. More puzzling are heritable polymorphisms with distinct morphologies, physiologies or behaviours maintained in populations despite their measurably lower reproductive success. But a complete model of evolution must also be able to accommodate these Darwinian paradoxes.

Raymond et al. (2023) investigate one such Darwinian paradox: In humans, male homosexual mate preference is heritable and is associated with a large reduction in offspring production but nonetheless occurs at relatively high frequencies in most human populations. Furthermore, multiple studies have found that homosexual men come from families that are, on average, larger than those of heterosexual men and that homosexual men have, on average, higher birth rank than do heterosexual men, i.e., having more older siblings and, particularly, more older brothers. Two types of mechanisms consistent with these observations have been proposed: 1) An evolutionary mechanism of sex-antagonistic pleiotropy, whereby highly fecund mothers are more likely to produce homosexual sons, and 2) A mechanistic explanation whereby successive male pregnancies alter the uterine environment by increasing the probability of an immune reaction by the mother to her male fetus, altering development of sexually dimorphic brain structures relevant to sexual orientation.

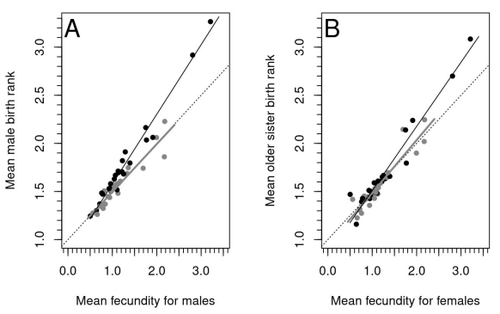

In this article, the authors explore these two mechanisms of sex-antagonistic effects (AE) and fraternal birth order effects (FBOE) and test how well they account for patterns of male homosexuality in population and family data. Clearly, these two effects are somewhat confounded because high birth ranks can only occur in large families. If, indeed, the probability of male homosexuality increases with increasing numbers of (maternal) older brothers, homosexual males will be more common in larger families. Similarly, if high female fecundity leads to a higher probability of male homosexuality via sex-antagonistic effects, homosexual males will, on average, have more older brothers. To disentangle the actions of these two effects the authors modelled the relationship between birth rank and population fecundity and investigated whether AE or FBOE modified this relationship for homosexual men. Simulation results were compared with aggregated population data from 13 countries. Family data on individuals’ sexual preference, birth rank and number of male and female siblings from France, Greece and Indonesia were analysed with generalised linear models and Bayesian approaches to test for a signal of AE or FBOE.

These analyses revealed a significant older-brother effect (FBOE) explaining patterns of occurrence of homosexuality in population and family data but no significant independent sex-antagonistic effect (AE). Thus larger family sizes of homosexual men appear due to the older-brother effect, with individuals of high birth rank coming necessarily from large sibships. The simulation approach also revealed that modelling a fraternal birth order effect (FBOE), such that individuals with more older brothers are more likely to be homosexual, generates an artefactual older sister effect simply because homosexual men are overrepresented at higher birth ranks. Older-sister effects reported in the literature may, therefore, be statistical artefacts of an underlying older-brother effect.

This paper is interesting for a number of reasons. It does an excellent job of explaining, identifying and dealing with estimation biases and testing for artefactual relationships generated by collinearity. It applies state-of-the art analytical/statistical tools. It breaks down two colinear effects and shows that only one really explains phenotypic variation. This is a great example of how to disentangle correlated variables that may or may not both contribute to trait variation. But most intriguingly, we are left without evidence for an evolutionary mechanism that compensates the large fitness cost associated with male homosexuality in humans. How can we explain high heritability maintained in the face of strong directional selection that should erode heritable genetic variation? The usual suspects include cryptic compensatory mechanisms yet to be discovered or flawed estimates of selection or heritability. For example, data on heritability of male homosexual mate preference in humans come from twin studies and twins share birth rank as well as alleles. Thus it is possible that heritability is over-estimated, including the environmental component associated with birth rank.

If, as the authors demonstrate here, birth rank is the strongest predictor of male homosexual mate preference, selection may be acting on a non-heritable plastic component of phenotypic variation. This could explain why heritable variation is not exhausted by selection, rendering the paradox less paradoxical, but fails to provide an adaptive explanation for the maintenance of male homosexual mate preference.

References

Raymond M., Turek D., Durand V., Nila S., Suryobroto B., Vadez J., Barthes J., Apostolou M. and Crochet P.-A. (2023) Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesis. bioRxiv, 2022.02.22.481477, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.22.481477