STEINER Ulrich Karl

- Institute of Biology, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Life History, Phenotypic Plasticity

- recommender

Recommendation: 1

Reviews: 0

Recommendation: 1

Individual differences in developmental trajectory leave a male polyphenic signature in bulb mite populations

What determines whether to scramble or fight in male bulb mites

Recommended by Ulrich Karl Steiner based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersA classic textbook example in evolutionary ecology for phenotypic plasticity—the expression of different phenotypes by a genotype under different environmental conditions—is on Daphnia (Dodson 1989). If various species of this small crustacean are exposed to predation risk or cues thereof, their offspring show induced defense phenotypes including helmets, neck teeth, or head- and tail-spines. These induced morphological changes lower the risk of being eaten by a predator. As in Daphnia, induction can span over generations, while other induced phenotypic plastic changes are almost instantaneous, including many responses in physiology and behaviour (Gabriel et al. 2005).

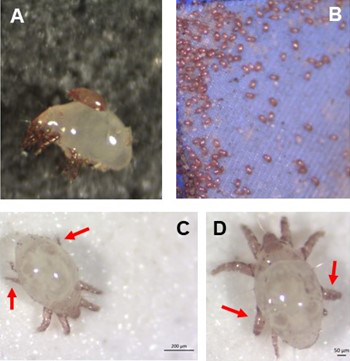

Larvae male bulb mites also show plasticity in morphologies throughout development. They can develop into a costly adult fighter morphology or a less costly, but vulnerable, scrambler type. The question Deere and Smallegange (Deere & Smallegange 2023) address is whether male bulb mite larvae can anticipate which type will likely be adaptive once they become adult, or alternatively, whether the resource availability or population density they experience during their larvae phase determines frequencies of adult scrambler and fighter types. They explore this question through experimental evolution, by removing different fractions of developing intermediate larva types. They thereby manipulate the stage structure of populations and alter selective forces on these stages. The potential shift of fixed genetics, imposed by the experimental selection regimes, is evaluated by fitness assays in green garden experiments.

The exciting extension to classical experiments on phenotypic plasticity is that the authors aim at exploring eco-evolutionary feedbacks experimentally in a system that is a little more complex than basic host-parasite or predator-prey systems. The latter involve, for instance, rotifer-algae dynamics (Yoshida et al. 2003; Becks et al. 2012) or similar simple lab systems for which eco-evolutionary feedbacks have been demonstrated. The challenge for the exploration of more complex systems is revealed in the study by Deere and Smallegange. Their findings suggest that the frequencies of adult male morphotype is triggered by the environmental condition (nutrient availability) during the larval phase, i.e. a simple environmental induced plastic response. No fixed genetic shift in determining adult morphotype frequencies occurs. The trigger at the larva phase remains also not perfectly determined in their experiments, as population density and resource (food) availability are partly confounded. Additional complexity and selective aspects come into play in this system, as the targeted developmental stages that develop into fighter male morphs are also dispersal morphs. If selection on dispersal to avoid residing in food-limited environments is strong, triggering genetic shifts in fighter morphs by local population structure might be hard to experimentally achieve. Small sample sizes limit conclusions on complex interactions among duration of the experiment, population size, developmental stage types, and adult fighter frequencies. The presented study (Deere & Smallegange 2023) helps to bridge theoretical predictions and empirical evidence for eco-evolutionary feedbacks that goes beyond simple ecological-driven changes in population dynamics (Govaert et al. 2019).

References

Becks, L., Ellner, S.P., Jones, L.E. & Hairston, N.G. (2012). The functional genomics of an eco-evolutionary feedback loop: linking gene expression, trait evolution, and community dynamics. Ecol. Lett., 15, 492-501.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01763.x

Deere, J.A. & Smallegange, I.M. (2023). Individual differences in developmental trajectory leave a male polyphenic signature in bulb mite populations. bioRxiv, 2023.02.06.527265, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology.

https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.06.527265

Dodson, S. (1989). Predator-induced Reaction Norms. Bioscience, 39, 447-452.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1311136

Gabriel, W., Luttbeg, B., Sih, A. & Tollrian, R. (2005). Environmental tolerance, heterogeneity, and the evolution of reversible plastic responses. Am. Nat., 166, 339-53.

https://doi.org/10.1086/432558

Govaert, L., Fronhofer, E.A., Lion, S., Eizaguirre, C., Bonte, D., Egas, M., et al. (2019). Eco-evolutionary feedbacks-Theoretical models and perspectives. Funct. Ecol., 33, 13-30.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13241

Yoshida, T., Jones, L.E., Ellner, S.P., Fussmann, G.F. & Hairston, N.G. (2003). Rapid evolution drives ecological dynamics in a predator-prey system. Nat. 2003 4246946, 424, 303-306.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01767