Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

08 Oct 2019

Strong habitat and weak genetic effects shape the lifetime reproductive success in a wild clownfish populationOcéane C. Salles, Glenn R. Almany, Michael L. Berumen, Geoffrey P. Jones, Pablo Saenz-Agudelo, Maya Srinivasan, Simon Thorrold, Benoit Pujol, Serge Planes https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3476529Habitat variation of wild clownfish population shapes selfrecruitment more than genetic effectsRecommended by Philip Munday based on reviews by Juan Diego Gaitan-Espitia and Loeske KruukEstimating the genetic and environmental components of variation in reproductive success is crucial to understanding the adaptive potential of populations to environmental change. To date, the heritability of lifetime reproductive success (fitness) has been estimated in a handful of wild animal population, mostly in mammals and birds, but has never been estimated for a marine species. The primary reason that such estimates are lacking in marine species is that most marine organisms have a dispersive larval phase, making it extraordinarily difficult to track the fate of offspring from one generation to the next. References [1] Salles, O. C., Almany, G. R., Berumen, M.L., Jones, G. P., Saenz-Agudelo, P., Srinivasan, M., Thorrold, S. R., Pujol, B., Planes, S. (2019). Strong habitat and weak genetic effects shape the lifetime reproductive success in a wild clownfish population. Zenodo, 3476529, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3476529 | Strong habitat and weak genetic effects shape the lifetime reproductive success in a wild clownfish population | Océane C. Salles, Glenn R. Almany, Michael L. Berumen, Geoffrey P. Jones, Pablo Saenz-Agudelo, Maya Srinivasan, Simon Thorrold, Benoit Pujol, Serge Planes | <p>Lifetime reproductive success (LRS), the number of offspring an individual contributes to the next generation, is of fundamental importance in ecology and evolutionary biology. LRS may be influenced by environmental, maternal and additive genet... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Quantitative Genetics | Philip Munday | 2018-10-01 09:00:53 | View | |

22 May 2023

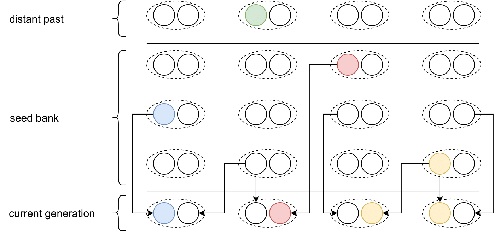

Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweepsKevin Korfmann, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.26.489499New insights into the dynamics of selective sweeps in seed-banked speciesRecommended by Renaud Vitalis based on reviews by Guillaume Achaz, Jere Koskela, William Shoemaker and Simon Boitard based on reviews by Guillaume Achaz, Jere Koskela, William Shoemaker and Simon Boitard

Many organisms across the Tree of life have the ability to produce seeds, eggs, cysts, or spores, that can remain dormant for several generations before hatching. This widespread adaptive trait in bacteria, fungi, plants and animals, has a significant impact on the ecology, population dynamics and population genetics of species that express it (Evans and Dennehy 2005). In population genetics, and despite the recognition of its evolutionary importance in many empirical studies, few theoretical models have been developed to characterize the evolutionary consequences of this trait on the level and distribution of neutral genetic diversity (see, e.g., Kaj et al. 2001; Vitalis et al. 2004), and also on the dynamics of selected alleles (see, e.g., Živković and Tellier 2018). However, due to the complexity of the interactions between evolutionary forces in the presence of dormancy, the fate of selected mutations in their genomic environment is not yet fully understood, even from the most recently developed models. In a comprehensive article, Korfmann et al. (2023) aim to fill this gap by investigating the effect of germ banking on the probability of (and time to) fixation of beneficial mutations, as well as on the shape of the selective sweep in their vicinity. To this end, Korfmann et al. (2023) developed and released their own forward-in-time simulator of genome-wide data, including neutral and selected polymorphisms, that makes use of Kelleher et al.’s (2018) tree sequence toolkit to keep track of gene genealogies. The originality of Korfmann et al.’s (2023) study is to provide new quantitative results for the effect of dormancy on the time to fixation of positively selected mutations, the shape of the genomic landscape in the vicinity of these mutations, and the temporal dynamics of selective sweeps. Their major finding is the prediction that germ banking creates narrower signatures of sweeps around positively selected sites, which are detectable for increased periods of time (as compared to a standard Wright-Fisher population). The availability of Korfmann et al.’s (2023) code will allow a wider range of parameter values to be explored, to extend their results to the particularities of the biology of many species. However, as they chose to extend the haploid coalescent model of Kaj et al. (2001), further development is needed to confirm the robustness of their results with a more realistic diploid model of seed dormancy. REFERENCES Evans, M. E. K., and J. J. Dennehy (2005) Germ banking: bet-hedging and variable release from egg and seed dormancy. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 80(4): 431-451. https://doi.org/10.1086/498282 Kaj, I., S. Krone, and M. Lascoux (2001) Coalescent theory for seed bank models. Journal of Applied Probability, 38(2): 285-300. https://doi.org/10.1239/jap/996986745 Kelleher, J., K. R. Thornton, J. Ashander, and P. L. Ralph (2018) Efficient pedigree recording for fast population genetics simulation. PLoS Computational Biology, 14(11): e1006581. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006581 Korfmann, K., D. Abu Awad, and A. Tellier (2023) Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweeps. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.26.489499 Vitalis, R., S. Glémin, and I. Olivieri (2004) When genes go to sleep: the population genetic consequences of seed dormancy and monocarpic perenniality. American Naturalist, 163(2): 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1086/381041 Živković, D., and A. Tellier (2018). All but sleeping? Consequences of soil seed banks on neutral and selective diversity in plant species. Mathematical Modelling in Plant Biology, 195-212. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99070-5_10 | Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweeps | Kevin Korfmann, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Seed banking (or dormancy) is a widespread bet-hedging strategy, generating a form of population overlap, which decreases the magnitude of genetic drift. The methodological complexity of integrating this trait impli... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics | Renaud Vitalis | 2022-05-23 13:01:57 | View | |

20 Dec 2017

Renewed diversification following Miocene landscape turnover in a Neotropical butterfly radiationNicolas Chazot, Keith R. Willmott, Gerardo Lamas, André V.L. Freitas, Florence Piron-Prunier, Carlos F. Arias, James Mallet, Donna Lisa De-Silva, Marianne Elias 10.1101/148189The influence of environmental change over geological time on the tempo and mode of biological diversification, revealed by Neotropical butterfliesRecommended by Richard H Ree based on reviews by Delano Lewis and 1 anonymous reviewerThe influence of environmental change over geological time on the tempo and mode of biological diversification is a hot topic in biogeography. Of central interest are questions about where, when, and how fast lineages proliferated, suffered extinction, and migrated in response to tectonic events, the waxing and waning of dominant biomes, etc. In this context, the dynamic conditions of the Miocene have received much attention, from studies of many clades and biogeographic regions. Here, Chazot et al. [1] present an exemplary analysis of butterflies (tribe Ithomiini) in the Neotropics, examining their diversification across the Andes and Amazon. They infer sharp contrasts between these regions in the late Miocene: accelerated diversification during orogeny of the Andes, and greater extinction in the Amazon associated during the Pebas system, with interchange and local diversification increasing following the Pebas during the Pliocene. References [1] Chazot N, Willmott KR, Lamas G, Freitas AVL, Piron-Prunier F, Arias CF, Mallet J, De-Silva DL and Elias M. 2017. Renewed diversification following Miocene landscape turnover in a Neotropical butterfly radiation. BioRxiv 148189, ver 4 of 19th December 2017. doi: 10.1101/148189 [2] Xing Y, and Ree RH. 2017. Uplift-driven diversification in the Hengduan Mountains, a temperate biodiversity hotspot. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114: E3444-E3451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616063114 | Renewed diversification following Miocene landscape turnover in a Neotropical butterfly radiation | Nicolas Chazot, Keith R. Willmott, Gerardo Lamas, André V.L. Freitas, Florence Piron-Prunier, Carlos F. Arias, James Mallet, Donna Lisa De-Silva, Marianne Elias | The Neotropical region has experienced a dynamic landscape evolution throughout the Miocene, with the large wetland Pebas occupying western Amazonia until 11-8 my ago and continuous uplift of the Andes mountains along the western edge of South Ame... |  | Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Richard H Ree | 2017-06-12 11:55:14 | View | |

31 Jul 2017

Selection on morphological traits and fluctuating asymmetry by a fungal parasite in the yellow dung flyWolf U. Blanckenhorn 10.1101/136325Parasite-mediated selection promotes small body size in yellow dung fliesRecommended by Rodrigo Medel based on reviews by Rodrigo Medel and 1 anonymous reviewerBody size has long been considered as one of the most important organismic traits influencing demographical processes, population size, and evolution of life history strategies [1, 2]. While many studies have reported a selective advantage of large body size, the forces that determine small-sized organisms are less known, and reports of negative selection coefficients on body size are almost absent at present. This lack of knowledge is unfortunate as climate change and energy demands in stressful environments, among other factors, may produce new selection scenarios and unexpected selection surfaces [3]. In this manuscript, Blanckenhorn [4] reports on a potential explanation for the surprising 10% body size decrease observed in a Swiss population of yellow dung flies during 1993 - 2009. The author took advantage of a fungus outbreak in 2002 to assess the putative role of the fungus Entomopthora scatophagae, a specific parasite of adult yellow dung flies, as selective force acting upon host body size. His findings indicate that, as expected by sexual selection theory, large males experience a mating advantage. However, this positive sexual selection is opposed by a strong negative selection on male and female body size through the viability fitness component. This study provides the first evidence of parasite-mediated disadvantage of large adult body size in the field. While further experimental work is needed to elucidate the exact causes of body size reduction in the population, the author proposes a variation of the trade-off hypothesis raised by Rantala & Roff [5] that large-sized individuals face an immunity cost due to their high absolute energy demands in stressful environments. References [1] Peters RH. 1983. The ecological implications of body size. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [2] Schmidt-Nielsen K. 1984. Scaling: why is animal size so important? Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [3] Ohlberger J. 2013. Climate warming and ectotherm body size: from individual physiology to community ecology. Functional Ecology 27: 991-1001. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12098 [4] Blanckenhorn WU. 2017. Selection on morphological traits and fluctuating asymmetry by a fungal parasite in the yellow dung fly. bioRxiv 136325, ver. 2 of 29th June 2017. doi: 10.1101/136325 [5] Rantala MJ & Roff DA. 2005. An analysis of trade-offs in immune function, body size and development time in the Mediterranean field cricket, Gryllus bimaculatus. Functional Ecology 19: 323-330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2005.00979.x | Selection on morphological traits and fluctuating asymmetry by a fungal parasite in the yellow dung fly | Wolf U. Blanckenhorn | Evidence for selective disadvantages of large body size remains scarce in general. Previous phenomenological studies of the yellow dung fly *Scathophaga stercoraria* have demonstrated strong positive sexual and fecundity selection on male and fema... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Sexual Selection | Rodrigo Medel | Rodrigo Medel | 2017-05-10 11:16:26 | View |

05 Oct 2017

Using Connectivity To Identify Climatic Drivers Of Local AdaptationStewart L. Macdonald, John Llewelyn, Ben Phillips 10.1101/145169A new approach to identifying drivers of local adaptationRecommended by Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer based on reviews by Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer and Thomas LenormandLocal adaptation, the higher fitness a population achieves in its local “home” environment relative to other environments is a crucial phase in the divergence of populations, and as such both generates and maintains diversity. Local adaptation is enhanced by selection and genetic variation in the relevant traits, and decreased by gene flow and genetic drift. Demonstrating local adaptation is laborious, and is typically done with a reciprocal transplant design [1], documenting repeated geographic clines [e.g. 2, 3] also provides strong evidence of local adaptation. Even when well documented, it is often unknown which aspects of the environment impose selection. Indeed, differences in environment between different sites that are measured during studies of local adaptation explain little of the variance in the degree of local adaptation [4]. This poses a problem to population management. Given climate change and habitat destruction, understanding the environmental drivers of local adaptation can be crucially important to conducting successful assisted migration or targeted gene flow. In this manuscript, Macdonald et al. [5] propose a means of identifying which aspects of the environment select for local adaptation without conducting a reciprocal transplant experiment. The idea is that the strength of relationships between traits and environmental variables that are due to plastic responses to the environment will not be influenced by gene flow, but the strength of trait-environment relationships that are due to local adaptation should decrease with gene flow. This then can be used to reduce the somewhat arbitrary list of environmental variables on which data are available down to a targeted list more likely to drive local adaptation in specific traits. To perform such an analysis requires three things: 1) measurements of traits of interest in a species across locations, 2) an estimate of gene flow between locations, which can be replaced with a biologically meaningful estimate of how well connected those locations are from the point of view of the study species, and 3) data on climate and other environmental variables from across a species’ range, many of which are available on line. Macdonald et al. [5] demonstrate their approach using a skink (Lampropholis coggeri). They collected morphological and physiological data on individuals from multiple populations. They estimated connectivity among those locations using information on habitat suitability and dispersal potential [6], and gleaned climatic data from available databases and the literature. They find that two physiological traits, the critical minimum and maximum temperatures, show the strongest signs of local adaptation, specifically local adaptation to annual mean precipitation, precipitation of the driest quarter, and minimum annual temperature. These are then aspects of skink phenotype and skink habitats that could be explored further, or could be used to provide background information if migration efforts, for example for genetic rescue [7] were initiated. The approach laid out has the potential to spark a novel genre of research on local adaptation. It its simplest form, knowing that local adaptation is eroded by gene flow, it is intuitive to consider that if connectivity reduces the strength of the relationship between an environmental variable and a trait, that the trait might be involved in local adaptation. The approach is less intuitive than that, however – it relies not connectivity per-se, but the interaction between connectivity and different environmental variables and how that interaction alters trait-environment relationships. The authors lay out a number of useful caveats and potential areas that could use further development. It will be interesting to see how the community of evolutionary biologists responds. References [1] Blanquart F, Kaltz O, Nuismer SL and Gandon S. 2013. A practical guide to measuring local adaptation. Ecology Letters, 16: 1195-1205. doi: 10.1111/ele.12150 [2] Huey RB, Gilchrist GW, Carlson ML, Berrigan D and Serra L. 2000. Rapid evolution of a geographic cline in size in an introduced fly. Science, 287: 308-309. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.308 [3] Milesi P, Lenormand T, Lagneau C, Weill M and Labbé P. 2016. Relating fitness to long-term environmental variations in natura. Molecular Ecology, 25: 5483-5499. doi: 10.1111/mec.13855 [4] Hereford, J. 2009. A quantitative survey of local adaptation and fitness trade-offs. The American Naturalist 173: 579-588. doi: 10.1086/597611 [5] Macdonald SL, Llewelyn J and Phillips BL. 2017. Using connectivity to identify climatic drivers of local adaptation. bioRxiv, ver. 4 of October 4, 2017. doi: 10.1101/145169 [6] Macdonald SL, Llewelyn J, Moritz C and Phillips BL. 2017. Peripheral isolates as sources of adaptive diversity under climate change. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 5:88. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2017.00088 [7] Whiteley AR, Fitzpatrick SW, Funk WC and Tallmon DA. 2015. Genetic rescue to the rescue. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30: 42-49. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.10.009 | Using Connectivity To Identify Climatic Drivers Of Local Adaptation | Stewart L. Macdonald, John Llewelyn, Ben Phillips | Despite being able to conclusively demonstrate local adaptation, we are still often unable to objectively determine the climatic drivers of local adaptation. Given the rapid rate of global change, understanding the climatic drivers of local adapta... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications | Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer | Thomas Lenormand | 2017-06-06 13:06:54 | View |

17 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Evolution of HIV virulence in response to widespread scale up of antiretroviral therapy: a modeling studyHerbeck JT, Mittler JE, Gottlieb GS, Goodreau SM, Murphy JT, Cori A, Pickles M, Fraser C 10.1093/ve/vew028Predicting HIV virulence evolution in response to widespread treatmentRecommended by Samuel Alizon and Roger Kouyos and Roger Kouyos

It is a classical result in the virulence evolution literature that treatments decreasing parasite replication within the host should select for higher replication rates, thus driving increased levels of virulence if the two are correlated. There is some evidence for this in vitro but very little in the field. HIV infections in humans offer a unique opportunity to go beyond the simple predictions that treatments should favour more virulent strains because many details of this host-parasite system are known, especially the link between set-point virus load, transmission rate and virulence. To tackle this question, Herbeck et al. [1] used a detailed individual-based model. This is original because it allows them to integrate existing knowledge from the epidemiology and evolution of HIV (e.g. recent estimates of the ‘heritability’ of set-point virus load from one infection to the next). This detailed model allows them to formulate predictions regarding the effect of different treatment policies; especially regarding the current policy switch away from treatment initiation based on CD4 counts towards universal treatment. The results show that, perhaps as expected from the theory, treatments based on the level of remaining host target cells (CD4 T cells) do not affect virulence evolution because they do not strongly affect the virulence level that maximizes HIV’s transmission potential. However, early treatments can lead to moderate increase in virulence within several years if coverage is high enough. These results seem quite robust to variation of all the parameters in realistic ranges. The great step forward in this model is the ability to obtain quantitative prediction regarding how a virus may evolve in response to public health policies. Here the main conclusion is that given our current knowledge in HIV biology, the risk of virulence evolution is perhaps more limited than expected from a direct application of virulence evolution model. Interestingly, the authors also conclude that recently observed increased in HIV virulence [2-3] cannot be explained by the impact of antiretroviral therapy alone; which raises the question about the main mechanism behind this increase. Finally, the authors make the interesting suggestion that “changing virulence is amenable to being monitored alongside transmitted drug resistance in sentinel surveillance”. References [1] Herbeck JT, Mittler JE, Gottlieb GS, Goodreau SM, Murphy JT, Cori A, Pickles M, Fraser C. 2016. Evolution of HIV virulence in response to widespread scale up of antiretroviral therapy: a modeling study. Virus Evolution 2:vew028. doi: 10.1093/ve/vew028 [2] Herbeck JT, Müller V, Maust BS, Ledergerber B, Torti C, et al. 2012. Is the virulence of HIV changing? A meta-analysis of trends in prognostic markers of HIV disease progression and transmission. AIDS 26:193-205. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834db418 [3] Pantazis N, Porter K, Costagliola D, De Luca A, Ghosn J, et al. 2014. Temporal trends in prognostic markers of HIV-1 virulence and transmissibility: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV 1:e119-26. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3018(14)00002-2 | Evolution of HIV virulence in response to widespread scale up of antiretroviral therapy: a modeling study | Herbeck JT, Mittler JE, Gottlieb GS, Goodreau SM, Murphy JT, Cori A, Pickles M, Fraser C | There are global increases in the use of HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART), guided by clinical benefits of early ART initiation and the efficacy of treatment as prevention of transmission. Separately, it has been shown theoretically and empirically... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Samuel Alizon | 2016-12-16 20:54:08 | View | |

12 Jun 2017

Modelling the evolution of how vector-borne parasites manipulate the vector's host choiceRecommended by Samuel Alizon based on reviews by Samuel Alizon and Nicole Mideo based on reviews by Samuel Alizon and Nicole Mideo

Many parasites can manipulate their hosts, thus increasing their transmission to new hosts [1]. This is particularly the case for vector-borne parasites, which can alter the feeding behaviour of their hosts. However, predicting the optimal strategy is not straightforward because three actors are involved and the interests of the parasite may conflict with that of the vector. There are few models that consider the evolution of host manipulation by parasites [but see 2-4], but there are virtually none that investigated how parasites can manipulate the host choice of vectors. Even on the empirical side, many aspects of this choice remain unknown. Gandon [5] develops a simple evolutionary epidemiology model that allows him to formulate clear and testable predictions. These depend on which actor controls the trait (the vector or the parasite) and, when there is manipulation, whether it is realised via infected hosts (to attract vectors) or infected vectors (to change host choice). In addition to clarifying the big picture, Gandon [5] identifies some nice properties of the model, for instance an independence of the density/frequency-dependent transmission assumption or a backward bifurcation at R0=1, which suggests that parasites could persist even if their R0 is driven below unity. Overall, this study calls for further investigation of the different scenarios with more detailed models and experimental validation of general predictions. References [1] Hughes D, Brodeur J, Thomas F. 2012. Host manipulation by parasites. Oxford University Press. [2] Brown SP. 1999. Cooperation and conflict in host-manipulating parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 266: 1899–1904. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0864 [3] Lion S, van Baalen M, Wilson WG. 2006. The evolution of parasite manipulation of host dispersal. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 273: 1063–1071. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3412 [4] Vickery WL, Poulin R. 2010. The evolution of host manipulation by parasites: a game theory analysis. Evolutionary Ecology 24: 773–788. doi: 10.1007/s10682-009-9334-0 [5] Gandon S. 2017. Evolution and manipulation of vector host choice. bioRxiv 110577, ver. 3 of 7th June 2017. doi: 10.1101/110577 | Evolution and manipulation of vector host choice | Sylvain Gandon | The transmission of many animal and plant diseases relies on the behavior of arthropod vectors. In particular, the choice to feed on either infected or uninfected hosts can dramatically affect the epidemiology of vector-borne diseases. I develop a... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Samuel Alizon | 2017-03-03 19:18:54 | View | |

09 Feb 2018

Phylodynamic assessment of intervention strategies for the West African Ebola virus outbreakSimon Dellicour, Guy Baele, Gytis Dudas, Nuno R. Faria, Oliver G. Pybus, Marc A. Suchard, Andrew Rambaut, Philippe Lemey https://doi.org/10.1101/163691Simulating the effect of public health interventions using dated virus sequences and geographical dataRecommended by Samuel Alizon based on reviews by Christian Althaus, Chris Wymant and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Christian Althaus, Chris Wymant and 1 anonymous reviewer

Perhaps because of its deadliness, the 2013-2016 Ebola Virus (EBOV) epidemics in West-Africa has led to unprecedented publication and sharing of full virus genome sequences. This was both rapid (90 full genomes were shared within weeks [1]) and important (more than 1500 full genomes have been released overall [2]). Furthermore, the availability of the metadata (especially GPS location) has led to depth analyses of the geographical spread of the epidemics [3]. References [1] Gire et al. 2014. Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the 2014 outbreak. Science 345: 1369–1372. doi: 10.1126/science.1259657. | Phylodynamic assessment of intervention strategies for the West African Ebola virus outbreak | Simon Dellicour, Guy Baele, Gytis Dudas, Nuno R. Faria, Oliver G. Pybus, Marc A. Suchard, Andrew Rambaut, Philippe Lemey | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100046). The recent Ebola virus (EBOV) outbreak in West Africa witnessed considerable efforts to obtain viral genom... |  | Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Samuel Alizon | 2017-09-30 13:49:57 | View | |

19 Jul 2021

Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasitesHannelore MacDonald, Erol Akçay, Dustin Brisson https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.13.435259Modelling parasitoid virulence evolution with seasonalityRecommended by Samuel Alizon based on reviews by Alex Best and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Alex Best and 2 anonymous reviewers

The harm most parasites cause to their host, i.e. the virulence, is a mystery because host death often means the end of the infectious period. For obligate killer parasites, or “parasitoids”, that need to kill their host to transmit to other hosts the question is reversed. Indeed, more rapid host death means shorter generation intervals between two infections and mathematical models show that, in the simplest settings, natural selection should always favour more virulent strains (Levin and Lenski, 1983). Adding biological details to the model modifies this conclusion and, for instance, if the relationship between the infection duration and the number of parasites transmission stages produced in a host is non-linear, strains with intermediate levels of virulence can be favoured (Ebert and Weisser 1997). Other effects, such as spatial structure, could yield similar effects (Lion and van Baalen, 2007). In their study, MacDonald et al. (2021) explore another type of constraint, which is seasonality. Earlier studies, such as that by Donnelly et al. (2013) showed that this constraint can affect virulence evolution but they had focused on directly transmitted parasites. Using a mathematical model capturing the dynamics of a parasitoid, MacDonald et al. (2021) show if two main assumptions are met, namely that at the end of the season only transmission stages (or “propagules”) survive and that there is a constant decay of these propagules with time, then strains with intermediate levels of virulence are favoured. Practically, the authors use delay differential equations and an adaptive dynamics approach to identify evolutionary stable strategies. As expected, the longer the short the season length, the higher the virulence (because propagule decay matters less). The authors also identify a non-linear relationship between the variation in host development time and virulence. Generally, the larger the variation, the higher the virulence because the parasitoid has to kill its host before the end of the season. However, if the variation is too wide, some hosts become physically impossible to use for the parasite, whence a decrease in virulence. Finally, MacDonald et ali. (2021) show that the consequence of adding trade-offs between infection duration and the number of propagules produced is in line with earlier studies (Ebert and Weisser 1997). These mathematical modelling results provide testable predictions for using well-described systems in evolutionary ecology such as daphnia parasitoids, baculoviruses, or lytic phages. Reference Donnelly R, Best A, White A, Boots M (2013) Seasonality selects for more acutely virulent parasites when virulence is density dependent. Proc R Soc B, 280, 20122464. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2464 Ebert D, Weisser WW (1997) Optimal killing for obligate killers: the evolution of life histories and virulence of semelparous parasites. Proc R Soc B, 264, 985–991. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1997.0136 Levin BR, Lenski RE (1983) Coevolution in bacteria and their viruses and plasmids. In: Futuyma DJ, Slatkin M eds. Coevolution. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc., 99–127. Lion S, van Baalen M (2008) Self-structuring in spatial evolutionary ecology. Ecol. Lett., 11, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01132.x MacDonald H, Akçay E, Brisson D (2021) Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasites. bioRxiv, 2021.03.13.435259, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.13.435259 | Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasites | Hannelore MacDonald, Erol Akçay, Dustin Brisson | <p style="text-align: justify;">The traditional mechanistic trade-offs resulting in a negative correlation between transmission and virulence are the foundation of nearly all current theory on the evolution of parasite virulence. Several ecologica... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Samuel Alizon | 2021-03-14 13:47:33 | View | |

04 Mar 2024

Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.).Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Aurore Bontemps, Julie Gauzere, Etienne Klein https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538521Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.)Recommended by Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Starting with the seminar paper by Lande & Arnold (1983), several studies have addressed phenotypic selection in natural populations of a wide variety of organisms, with a recent renewed interest in forest trees (e.g., Oddou-Muratorio et al. 2018; Alexandre et al. 2020; Westergren et al. 2023). Because of their long generation times, long-lived organisms such as forest trees may suffer the most from maladaptation due to climate change, and whether they will be able to adapt to new environmental conditions in just one or a few generations is hotly debated. In this study, Oddou-Muratorio and colleagues (2024) extend the current framework to add two additional selection components that may alter patterns of fecundity selection and the estimation of standard selection gradients, namely sexual selection (evaluated as differences in flowering phenology conducting to assortative mating) and growth (viability) selection. Notably, the study is conducted in two contrasted environments (low vs high altitude populations) providing information on how the environment may modulate selection patterns in spring phenology. Spring phenology is a key adaptive trait that has been shown to be already affected by climate change in forest trees (Alberto et al. 2013). While fecundity selection for early phenology has been extensively reported before (see Munguía-Rosas et al. 2011), the authors found that this kind of selection can be strongly modulated by sexual selection, depending on the environment. Moreover, they found a significant correlation between early phenology and seedling growth in a common garden, highlighting the importance of this trait for early survival in European beech. As a conclusion, this original research puts in evidence the need for more integrative approaches for the study of natural selection in the field, as well as the importance of testing multiple environments and the relevance of common gardens to further evaluate phenotypic changes due to real-time selection. PS: The recommender and the first author of the preprint have shared authorship in a recent paper in a similar topic (Westergren et al. 2023). Nevertheless, the recommender has not contributed in any way or was aware of the content of the current preprint before acting as recommender, and steps have been taken for a fair and unpartial evaluation. References Alberto, F. J., Aitken, S. N., Alía, R., González‐Martínez, S. C., Hänninen, H., Kremer, A., Lefèvre, F., Lenormand, T., Yeaman, S., Whetten, R., & Savolainen, O. (2013). Potential for evolutionary responses to climate change - evidence from tree populations. Global Change Biology, 19(6), 1645‑1661. Oddou-Muratorio S, Bontemps A, Gauzere J, Klein E (2024) Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). bioRxiv, 2023.04.27.538521, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538521 Oddou-Muratorio, S., Gauzere, J., Bontemps, A., Rey, J.-F., & Klein, E. K. (2018). Tree, sex and size: Ecological determinants of male vs. female fecundity in three Fagus sylvatica stands. Molecular Ecology, 27(15), 3131‑3145. | Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (*Fagus sylvatica* L.). | Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Aurore Bontemps, Julie Gauzere, Etienne Klein | <p>Background: Plant phenological traits such as the timing of budburst or flowering can evolve on ecological timescales through response to fecundity and viability selection. However, interference with sexual selection may arise from assortative ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez | 2023-05-02 11:57:23 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer