Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▲ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

08 Jan 2024

Genomic relationships among diploid and polyploid species of the genus Ludwigia L. section Jussiaea using a combination of molecular cytogenetic, morphological, and crossing investigationsD. Barloy, L. Portillo - Lemus, S. A. Krueger-Hadfield, V. Huteau, O. Coriton https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.02.522458Deciphering the genomic composition of tetraploid, hexaploid and decaploid Ludwigia L. species (section Jussiaea)Recommended by Malika AINOUCHE based on reviews by Alex BAUMEL and Karol MARHOLDPolyploidy, which results in the presence of more than two sets of homologous chromosomes represents a major feature of plant genomes that have undergone successive rounds of duplication followed by more or less rapid diploidization during their evolutionary history. Polyploid complexes containing diploid and derived polyploid taxa are excellent model systems for understanding the short-term consequences of whole genome duplication, and have been particularly well-explored in evolutionary ecology (Ramsey and Ramsey 2014, Rice et al. 2019). Many polyploids (especially when resulting from interspecific hybridization, i.e. allopolyploids) are successful invaders (te Beest et al. 2012) as a result of rapid genome dynamics, functional novelty, and trait evolution. The origin (parental legacy) and modes of formation of polyploids have a critical impact on the subsequent polyploid evolution. Thus, elucidation of the genomic composition of polyploids is fundamental to understanding trait evolution, and such knowledge is still lacking for many invasive species. Genus Ludwigia is characterized by a complex taxonomy, with an underexplored evolutionary history. Species from section Jussieae form a polyploid complex with diploids, tetraploids, hexaploids, and decaploids that are notorious invaders in freshwater and riparian ecosystems (Thouvenot et al.2013). Molecular phylogeny of the genus based on nuclear and chloroplast sequences (Liu et al. 2027) suggested some relationships between diploid and polyploid species, without fully resolving the question of the parentage of the polyploids. In their study, Barloy et al. (2023) have used a combination of molecular cytogenetics (Genomic In situ Hybridization), morphology and experimental crosses to elucidate the genomic compositions of the polyploid species, and show that the examined polyploids are of hybrid origin (allopolyploids). The tetraploid L. stolonifera derives from the diploids L. peploides subsp. montevidensis (AA genome) and L. helminthorhiza (BB genome). The tetraploid L. ascendens also share the BB genome combined with an undetermined different genome. The hexaploid L. grandiflora subsp. grandiflora has inherited the diploid AA genome combined with additional unidentified genomes. The decaploid L. grandiflora subsp. hexapetala has inherited the tetraploid L. stolonifera and the hexaploid L. grandiflora subsp. hexapetala genomes. As the authors point out, further work is needed, including additional related diploid (e.g. other subspecies of L. peploides) or tetraploid (L. hookeri and L. peduncularis) taxa that remain to be investigated, to address the nature of the undetermined parental genomes mentioned above. The presented work (Barloy et al. 2023) provides significant knowledge of this poorly investigated group with regard to genomic information and polyploid origin, and opens perspectives for future studies. The authors also detect additional diagnostic morphological traits of interest for in-situ discrimination of the taxa when monitoring invasive populations. References Barloy D., Portillo-Lemus L., Krueger-Hadfield S.A., Huteau V., Coriton O. (2024). Genomic relationships among diploid and polyploid species of the genus Ludwigia L. section Jussiaea using a combination of molecular cytogenetic, morphological, and crossing investigations. BioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.02.522458 te Beest M., Le Roux J.J., Richardson D.M., Brysting A.K., Suda J., Kubešová M., Pyšek P. (2012). The more the better? The role of polyploidy in facilitating plant invasions. Annals of Botany, Volume 109, Issue 1 Pages 19–45, https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcr277 Ramsey J. and Ramsey T. S. (2014). Ecological studies of polyploidy in the 100 years following its discovery Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B369 1–20 https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0352 Rice, A., Šmarda, P., Novosolov, M. et al. (2019). The global biogeography of polyploid plants. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0787-9 Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiebaut G. (2013). A success story: Water primroses, aquatic plant pests. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 23:790–803 https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2387 | Genomic relationships among diploid and polyploid species of the genus *Ludwigia* L. section *Jussiaea* using a combination of molecular cytogenetic, morphological, and crossing investigations | D. Barloy, L. Portillo - Lemus, S. A. Krueger-Hadfield, V. Huteau, O. Coriton | <p>ABSTRACTThe genus Ludwigia L. sectionJussiaeais composed of a polyploid species complex with 2x, 4x, 6x and 10x ploidy levels, suggesting possible hybrid origins. The aim of the present study is to understand the genomic relationships among dip... |  | Hybridization / Introgression, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Malika AINOUCHE | 2023-01-11 13:47:18 | View | |

11 Jun 2019

A bird’s white-eye view on neosex chromosome evolutionThibault Leroy, Yoann Anselmetti, Marie-Ka Tilak, Sèverine Bérard, Laura Csukonyi, Maëva Gabrielli, Céline Scornavacca, Borja Milá, Christophe Thébaud, Benoit Nabholz https://doi.org/10.1101/505610Young sex chromosomes discovered in white-eye birdsRecommended by Kateryna Makova based on reviews by Gabriel Marais, Melissa Wilson and 1 anonymous reviewerRecent advances in next-generation sequencing are allowing us to uncover the evolution of sex chromosomes in non-model organisms. This study [1] represents an example of this application to birds of two Sylvioidea species from the genus Zosterops (commonly known as white-eyes). The study is exemplary in the amount and types of data generated and in the thoroughness of the analysis applied. Both male and female genomes were sequenced to allow the authors to identify sex-chromosome specific scaffolds. These data were augmented by generating the transcriptome (RNA-seq) data set. The findings after the analysis of these extensive data are intriguing: neoZ and neoW chromosome scaffolds and their breakpoints were identified. Novel sex chromosome formation appears to be accompanied by translocation events. The timing of formation of novel sex chromosomes was identified using molecular dating and appears to be relatively recent. Yet first signatures of distinct evolutionary patterns of sex chromosomes vs. autosomes could be already identified. These include the accumulation of transposable elements and changes in GC content. The changes in GC content could be explained by biased gene conversion and altered recombination landscape of the neo sex chromosomes. The authors also study divergence and diversity of genes located on the neo sex chromosomes. Here their findings appear to be surprising and need further exploration. The neoW chromosome already shows unique patterns of divergence and diversity at protein-coding genes as compared with genes on either neoZ or autosomes. In contrast, the genes on the neoZ chromosome do not display divergence or diversity patterns different from those for autosomes. This last observation is puzzling and I believe should be explored in further studies. Overall, this study significantly advances our knowledge of the early stages of sex chromosome evolution in vertebrates, provides an example of how such a study could be conducted in other non-model organisms, and provides several avenues for future work. References [1] Leroy T., Anselmetti A., Tilak M.K., Bérard S., Csukonyi L., Gabrielli M., Scornavacca C., Milá B., Thébaud C. and Nabholz B. (2019). A bird’s white-eye view on neo-sex chromosome evolution. bioRxiv, 505610, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/505610 | A bird’s white-eye view on neosex chromosome evolution | Thibault Leroy, Yoann Anselmetti, Marie-Ka Tilak, Sèverine Bérard, Laura Csukonyi, Maëva Gabrielli, Céline Scornavacca, Borja Milá, Christophe Thébaud, Benoit Nabholz | <p>Chromosomal organization is relatively stable among avian species, especially with regards to sex chromosomes. Members of the large Sylvioidea clade however have a pair of neo-sex chromosomes which is unique to this clade and originate from a p... |  | Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Kateryna Makova | 2019-01-24 14:17:15 | View | |

05 Apr 2024

Does the seed fall far from the tree? Weak fine scale genetic structure in a continuous Scots pine populationAlina K. Niskanen, Sonja T. Kujala, Katri Kärkkäinen, Outi Savolainen, Tanja Pyhäjärvi https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.16.545344Weak spatial genetic structure in a large continuous Scots pine population – implications for conservation and breedingRecommended by Myriam Heuertz based on reviews by Joachim Mergeay, Jean-Baptiste Ledoux and Roberta Loh based on reviews by Joachim Mergeay, Jean-Baptiste Ledoux and Roberta Loh

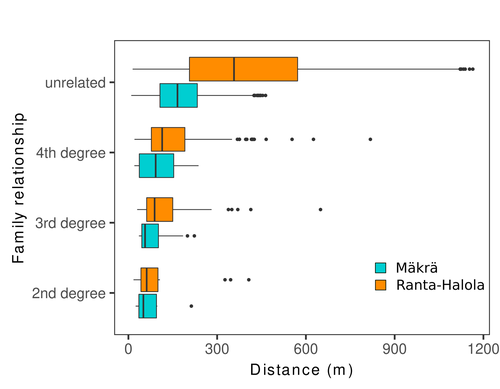

Spatial genetic structure, i.e. the non-random spatial distribution of genotypes, arises in populations because of different processes including spatially limited dispersal and selection. Knowledge on the spatial genetic structure of plant populations is important to assess biological parameters such as gene dispersal distances and the potential for local adaptations, as well as for applications in conservation management and breeding. In their work, Niskanen and colleagues demonstrate a multifaceted approach to characterise the spatial genetic structure in two replicate sites of a continuously distributed Scots pine population in South-Eastern Finland. They mapped and assessed the ages of 469 naturally regenerated adults and genotyped them using a SNP array which resulted in 157 325 filtered polymorphic SNPs. Their dataset is remarkably powerful because of the large numbers of both individuals and SNPs genotyped. This made it possible to characterise precisely the decay of genetic relatedness between individuals with spatial distance despite the extensive dispersal capacity of Scots pine through pollen, and ensuing expectations of an almost panmictic population. The authors’ data analysis was particularly thorough. They demonstrated that two metrics of pairwise relatedness, the genomic relationship matrix (GRM, Yang et al. 2011) and the kinship coefficient (Loiselle et al. 1995) were strongly correlated and produced very similar inference of family relationships: >99% of pairs of individuals were unrelated, and the remainder exhibited 2nd (e.g., half-siblings) to 4th degree relatedness. Pairwise relatedness decayed with spatial distance which resulted in extremely weak but statistically significant spatial genetic structure in both sites, quantified as Sp=0.0005 and Sp=0.0008. These estimates are at least an order of magnitude lower than estimates in the literature obtained in more fragmented populations of the same species or in other conifers. Estimates of the neighbourhood size, the effective number of potentially mating individuals belonging to a within-population neighbourhood (Wright 1946), were relatively large with Nb=1680-3210 despite relatively short gene dispersal distances, σg = 36.5–71.3m, which illustrates the high effective density of the population. The authors showed the implications of their findings for selection. The capacity for local adaptation depends on dispersal distances and the strength of the selection coefficient. In the study population, the authors inferred that local adaptation can only occur if environmental heterogeneity occurs over a distance larger than approximately one kilometre (or larger, if considering long-distance dispersal). Interestingly, in Scots pine, no local adaptation has been described on similar geographic scales, in contrast to some other European or Mediterranean conifers (Scotti et al. 2023). The authors’ results are relevant for the management of conservation and breeding. They showed that related individuals occurred within sites only and that they shared a higher number of rare alleles than unrelated ones. Since rare alleles are enriched in new and recessive deleterious variants, selecting related individuals could have negative consequences in breeding programmes. The authors also showed, in their response to reviewers, that their powerful dataset was not suitable to obtain a robust estimate of effective population size, Ne, based on the linkage disequilibrium method (Do et al. 2014). This illustrated that the estimation of Ne used for genetic indicators supported in international conservation policy (Hoban et al. 2020, CBD 2022) remains challenging in large and continuous populations (see also Santo-del-Blanco et al. 2023, Gargiulo et al. 2024). ReferencesCBD (2022) Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf Do C, Waples RS, Peel D, Macbeth GM, Tillett BJ, Ovenden JR (2014). NeEstimator v2: re-implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne ) from genetic data. Molecular Ecology Resources 14: 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12157 Gargiulo R, Decroocq V, González-Martínez SC, Paz-Vinas I, Aury JM, Kupin IL, Plomion C, Schmitt S, Scotti I, Heuertz M (2024) Estimation of contemporary effective population size in plant populations: limitations of genomic datasets. Evolutionary Applications, in press, https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.18.549323 Hoban S, Bruford M, D’Urban Jackson J, Lopes-Fernandes M, Heuertz M, Hohenlohe PA, Paz-Vinas I, et al. (2020) Genetic diversity targets and indicators in the CBD post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework must be improved. Biological Conservation 248: 108654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108654 Loiselle BA, Sork VL, Nason J & Graham C (1995) Spatial genetic structure of a tropical understorey shrub, Psychotria officinalis (Rubiaceae). American Journal of Botany 82: 1420–1425. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1995.tb12679.x Santos-del-Blanco L, Olsson S, Budde KB, Grivet D, González-Martínez SC, Alía R, Robledo-Arnuncio JJ (2022). On the feasibility of estimating contemporary effective population size (Ne) for genetic conservation and monitoring of forest trees. Biological Conservation 273: 109704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109704 Scotti I, Lalagüe H, Oddou-Muratorio S, Scotti-Saintagne C, Ruiz Daniels R, Grivet D, et al. (2023) Common microgeographical selection patterns revealed in four European conifers. Molecular Ecology 32: 393-411. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16750 Wright S (1946) Isolation by distance under diverse systems of mating. Genetics 31: 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/31.1.39 Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME & Visscher PM (2011) GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. The American Journal of Human Genetics 88: 76–82. https://www.cell.com/ajhg/pdf/S0002-9297(10)00598-7.pdf | Does the seed fall far from the tree? Weak fine scale genetic structure in a continuous Scots pine population | Alina K. Niskanen, Sonja T. Kujala, Katri Kärkkäinen, Outi Savolainen, Tanja Pyhäjärvi | <p>Knowledge of fine-scale spatial genetic structure, i.e., the distribution of genetic diversity at short distances, is important in evolutionary research and in practical applications such as conservation and breeding programs. In trees, related... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Population Genetics / Genomics | Myriam Heuertz | Joachim Mergeay | 2023-06-27 21:57:28 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer