CONDAMINE Fabien

- UMR 5554 Institut des Sciences de l'Evolution (Université de Montpellier), CNRS, Montpellier, France

- Macroevolution, Paleontology, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Systematics / Taxonomy

- recommender

Recommendations: 3

Reviews: 0

Recommendations: 3

Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architecture

Macroevolutionary drivers of brain evolution in primates

Recommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by Paula Gonzalez, Orlin Todorov and 3 anonymous reviewersStudying the evolution of animal cognition is challenging because many environmental and species-related factors can be intertwined, which is further complicated when looking at deep-time evolution. Previous knowledge has emphasized the role of intraspecific interactions in affecting the socio-ecological environment shaping cognition. However, much less is known about such an effect at the interspecific level. Yet, the coexistence of different species in the same geographic area at a given time (sympatry) can impact the evolutionary history of species through character displacement due to biotic interactions. Trait evolution has been observed and tested with morphological external traits but more rarely with brain evolution. Compared to most species’ traits, brain evolution is even more delicate to assess since specific brain regions can be involved in different functions, may they be individual-based and social-based information processing.

In a very original and thoroughly executed study, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) addressed the question: How does the co-occurrence of congeneric species shape brain evolution and influence species diversification? By considering brain size as a proxy for cognition, they evaluated whether species sympatry impacted the evolution of cognition in frugivorous primates. Fruit resources are hard to find, not continuous through time, heterogeneously distributed across space, but can be predictable. Hence, cognition considerably shapes the foraging strategy and competition for food access can be fierce. Over long timescales, it remains unclear whether brain size and the pace of species diversification are linked in the context of sympatry, and if so how. Recent studies have found that larger brain sizes can be associated with higher diversification rates in birds (Sayol et al. 2019). Similarly, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) thus wondered if the evolution of brain size in primates impacted their dynamic of species diversification, which has been suggested (Melchionna et al. 2020) but not tested.

Prior to anything, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) had to retrace the evolutionary history of sympatry between frugivorous primate lineages through time using the primate tree of life, species’ extant distribution, and process-based models to estimate ancestral range evolution. To infer the effect of species sympatry on the evolution of cognition in frugivorous primates, the authors evaluated the support for phylogenetic models of brain size evolution accounting or not for species sympatry and investigated the directionality of the selection induced by sympatry on brain size evolution. Finally, to better understand the impact of cognition and interactions between primates on their evolutionary success, they tested for correlations between brain size or species’ sympatry and species diversification.

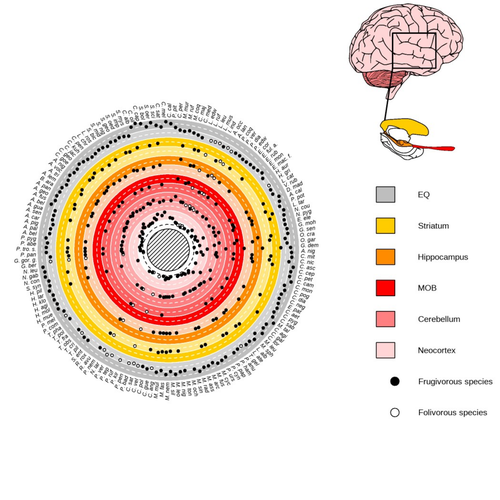

Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) found that the evolution of the whole brain or brain regions used in immediate information processing was best fitted with models not considering sympatry. By contrast, models considering species sympatry best predicted the evolution of brain regions related to long-term memory of interactions with the socio-ecological environment, with a decrease in their size along with stronger sympatry. Specifically, they found that sympatry was associated with a decrease in the relative size of the hippocampus and striatum, but had no significant effect on the neocortex, cerebellum, or overall brain size.

The hippocampus is a brain region that plays a crucial role in processing and memorizing spatiotemporal information, which is relevant for frugivorous primates in their foraging behavior. The study suggests that competition between sympatric species for limited food resources may lead to a more complex and unpredictable food distribution, which may in turn render cognitive foraging not advantageous and result in a selection for smaller brain regions involved in foraging. Niche partitioning and dietary specialization in sympatry may also impact cognitive abilities, with more specialized diets requiring lower cognitive abilities and smaller brain region sizes.

On the other hand, the absence of an effect of sympatry on brain regions involved in immediate sensory information processing, such as the cerebellum and neocortex, suggests that foragers do not exploit cues left out by sympatric heterospecific species, or they may discard environmental cues in favor of social cues.

This is a remarkable study that highlights the importance of considering the impact of ecological factors, such as sympatry, on the evolution of specific brain regions involved in cognitive processes, and the potential trade-offs in brain region size due to niche partitioning and dietary specialization in sympatry. Further research is needed to explore the mechanisms behind these effects and to test for the possible role of social cues in the evolution of brain regions. This study provides insights into the selective pressures that shape brain evolution in primates.

References

Melchionna M, Mondanaro A, Serio C, Castiglione S, Di Febbraro M, Rook L, Diniz-Filho JAF, Manzi G, Profico A, Sansalone G, Raia P (2020) Macroevolutionary trends of brain mass in Primates. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 129, 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blz161

Robira B, Perez-Lamarque B (2023) Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architecture. bioRxiv, 2022.05.09.490912, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.09.490912

Sayol F, Lapiedra O, Ducatez S, Sol D (2019) Larger brains spur species diversification in birds. Evolution, 73, 2085–2093. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13811

Systematics and geographical distribution of Galba species, a group of cryptic and worldwide freshwater snails

The challenge of delineating species when they are hidden

Recommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by Pavel Matos, Christelle Fraïsse and Niklas WahlbergThe science of naming species (taxonomy) has been renewed with the developments of molecular sequencing, digitization of museum specimens, and novel analytical tools. However, naming species can be highly subjective, sometimes considered as an art [1], because it is based on human-based criteria that vary among taxonomists. Nonetheless, taxonomists often argue that species names are hypotheses, which are therefore testable and refutable as new evidence is provided. This challenge comes with a more and more recognized and critical need for rigorously delineated species not only for producing accurate species inventories, but more importantly many questions in evolutionary biology (e.g. speciation), ecology (e.g. ecosystem structure and functioning), conservation biology (e.g. targeting priorities) or biogeography (e.g. diversification processes) depend in part on those species inventories and our knowledge of species [2-3]. Inaccurate species boundaries or diversity estimates may lead us to deliver biased answers to those questions, exactly as phylogenetic trees must be reconstructed rigorously and analyzed critically because they are a first step toward discussing broader questions [2-3]. In this context, biological diversity needs to be studied from multiple and complementary perspectives requiring the collaboration of morphologists, molecular biologists, biogeographers, and modelers [4-5]. Integrative taxonomy has been proposed as a solution to tackle the challenge of delimiting species [2], especially in highly diverse and undocumented groups of organisms.

In an elegant study that harbors all the characteristics of an integrative approach, Alda et al. [6] tackle the delimitation of species within the snail genus Galba (Lymnaeidae). Snails of this genus represent a peculiar case study for species delineation with a long and convoluted taxonomic history in which previous works recognized a number of species ranging from 4 to 30. The confusion is likely due to a loose morphology (labile shell features and high plasticity), which makes the identification and naming of species very unstable and likely subjective. An integrative taxonomic approach was needed. After two decades of taxon sampling and visits of type localities, the authors present an impressively dense taxon sampling at a global scale for the genus, which includes all described species. When it comes to delineate species, taxon sampling is often the key if we want to embrace the genetic and morphological diversity. Molecular data was obtained for several types of markers (microsatellites and DNA sequences for four genes), which were combined to morphology of shell and of internal organs, and to geographic distribution. All the data are thoroughly analyzed with cutting-edge methods starting from Bayesian phylogenetic reconstructions using multispecies coalescent models, followed by models of species delimitation based on the molecular specimen-level phylogeny, and then Bayesian divergence time estimates. They also used probabilistic models of ancestral state estimation to infer the ancestral phenotypic state of the Galba ancestors.

Their numerous phylogenetic and delimitation analyses allow to redefine the species boundaries that indicate that the genus Galba comprises six species. Interestingly, four of these species are morphologically cryptic and likely constitute species with extensive genetic diversity and widespread geographic distribution. The other two species have more geographically restricted distributions and exhibit an alternative morphology that is more phylogenetically derived than the cryptic one. Although further genomic studies would be required to strengthen some species status, this novel delimitation of Galba species has important implications for our understanding of convergence and morphological stasis, or the role for stabilizing selection in amphibious habitats; topics that are rarely addressed with invertebrate groups. For instance, in terms of macroevolutionary history, it is striking that an invertebrate clade of that age (22 million years ago) has only given birth to six species today. Including 30 (ancient taxonomy) or 6 (integrative taxonomy) species in a similar amount of evolutionary time does not tell us the same story when studying the diversification processes [7]. Here, Alda et al. [6] present a convincing case study that should foster similar studies following their approach, which will provide stimulating perspectives for testing the concepts of species and their effects on evolutionary biology.

References

[1] Ohl, M. (2018). The art of naming. MIT Press.

[2] Dayrat, B. (2005). Towards integrative taxonomy. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 85(3), 407–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00503.x

[3] De Queiroz, K. (2007). Species concepts and species delimitation. Systematic Biology, 56(6), 879–886. doi: 10.1080/10635150701701083

[4] Padial, J. M., Miralles, A., De la Riva, I., and Vences, M. (2010). The integrative future of taxonomy. Frontiers in Zoology, 7(1), 16. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-7-16

[5] Schlick-Steiner, B. C., Steiner, F. M., Seifert, B., Stauffer, C., Christian, E., and Crozier, R. H. (2010). Integrative taxonomy: A multisource approach to exploring biodiversity. Annual Review of Entomology, 55(1), 421–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085432

[6] Alda, P. et al. (2019). Systematics and geographical distribution of Galba species, a group of cryptic and worldwide freshwater snails. BioRxiv, 647867, v3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/647867

[7] Ruane, S., Bryson, R. W., Pyron, R. A., and Burbrink, F. T. (2014). Coalescent species delimitation in milksnakes (Genus Lampropeltis) and impacts on phylogenetic comparative analyses. Systematic Biology, 63(2), 231–250. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syt099

Pleistocene climate change and the formation of regional species pools

Recent assembly of European biogeographic species pool

Recommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersBiodiversity is unevenly distributed over time, space and the tree of life [1]. The fact that regions are richer than others as exemplified by the latitudinal diversity gradient has fascinated biologists as early as the first explorers travelled around the world [2]. Provincialism was one of the first general features of land biotic distributions noted by famous nineteenth century biologists like the phytogeographers J.D. Hooker and A. de Candolle, and the zoogeographers P.L. Sclater and A.R. Wallace [3]. When these explorers travelled among different places, they were struck by the differences in their biotas (e.g. [4]). The limited distributions of distinctive endemic forms suggested a history of local origin and constrained dispersal. Much biogeographic research has been devoted to identifying areas where groups of organisms originated and began their initial diversification [3]. Complementary efforts found evidence of both historical barriers that blocked the exchange of organisms between adjacent regions and historical corridors that allowed dispersal between currently isolated regions. The result has been a division of the Earth into a hierarchy of regions reflecting patterns of faunal and floral similarities (e.g. regions, subregions, provinces). Therefore a first ensuing question is: “how regional species pools have been assembled through time and space?”, which can be followed by a second question: “what are the ecological and evolutionary processes leading to differences in species richness among species pools?”.

To address these questions, the study of Calatayud et al. [5] developed and performed an interesting approach relying on phylogenetic data to identify regional and sub-regional pools of European beetles (using the iconic ground beetle genus Carabus). Specifically, they analysed the processes responsible for the assembly of species pools, by comparing the effects of dispersal barriers, niche similarities and phylogenetic history. They found that Europe could be divided in seven modules that group zoogeographically distinct regions with their associated faunas, and identified a transition zone matching the limit of the ice sheets at Last Glacial Maximum (19k years ago). Deviance of species co-occurrences across regions, across sub-regions and within each region was significantly explained, primarily by environmental niche similarity, and secondarily by spatial connectivity, except for northern regions. Interestingly, southern species pools are mostly separated by dispersal barriers, whereas northern species pools are mainly sorted by their environmental niches. Another important finding of Calatayud et al. [5] is that most phylogenetic structuration occurred during the Pleistocene, and they show how extreme recent historical events (Quaternary glaciations) can profoundly modify the composition and structure of geographic species pools, as opposed to studies showing the role of deep-time evolutionary processes.

The study of biogeographic assembly of species pools using phylogenies has never been more exciting and promising than today. Catalayud et al. [5] brings a nice study on the importance of Pleistocene glaciations along with geographical barriers and niche-based processes in structuring the regional faunas of European beetles. The successful development of powerful analytical tools in recent years, in conjunction with the rapid and massive increase in the availability of biological data (including molecular phylogenies, fossils, georeferrenced occurrences and ecological traits), will allow us to disentangle complex evolutionary histories. Although we still face important limitations in data availability and methodological shortcomings, the last decade has witnessed an improvement of our understanding of how historical and biotic triggers are intertwined on shaping the Earth’s stupendous biological diversity. I hope that the Catalayud et al.’s approach (and analytical framework) will help movement in that direction, and that it will provide interesting perspectives for future investigations of other regions. Applied to a European beetle radiation, they were able to tease apart the relative contributions of biotic (niche-based processes) versus abiotic (geographic barriers and climate change) factors.

References

[1] Rosenzweig ML. 1995. Species diversity in space and time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[2] Mittelbach GG, Schemske DW, Cornell HV, Allen AP, Brown JM et al. 2007. Evolution and the latitudinal diversity gradient: speciation, extinction and biogeography. Ecology Letters. 10: 315–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01020.x

[3] Lomolino MV, Riddle BR, Whittaker RJ and Brown JH. 2010. Biogeography, 4th edn. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, MA.

[4] Wallace AR. 1876. The geographical distribution of animals: with a study of the relations of living and extinct faunas as elucidating the past changes of the earth's surface. New York: Harper and Brothers, Publishers.

[5] Calatayud J, Rodríguez MÁ, Molina-Venegas R, Leo M, Hórreo JL and Hortal J. 2018. Pleistocene climate change and the formation of regional species pools. bioRxiv 149617 ver. 4 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/149617