KÄFER Jos

- Institut des Sciences de l'Evolution de Montpellier, CNRS, Univ. Montpellier, Montpellier, France

- Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex

- recommender

Recommendation: 1

Reviews: 0

Recommendation: 1

Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes?

New modelling results help understanding the evolution and maintenance of recombination suppression involving sex chromosomes

Recommended by Jos Käfer based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersDespite advances in genomic research, many views of genome evolution are still based on what we know from a handful of species, such as humans. This also applies to our knowledge of sex chromosomes. We've apparently been too much used to the situation in which a highly degenerate Y chromosome coexists with an almost normal X chromosome to be able to fully grasp all the questions implied by this situation. Lately, many more sex chromosomes have been studied in other organisms, such as in plants, and the view is changing radically: there is a large diversity of situations, ranging from young highly divergent sex chromosomes to old ones that are so similar that they're hard to detect. Undoubtedly inspired by these recent findings, a few theoretical studies have been published around 2 years ago that put an entirely new light on the evolution of sex chromosomes. The differences between these models have however remained somewhat difficult to appreciate by non-specialists.

In particular, the models by Lenormand & Roze (2022) and by Jay et al. (2022) seemed quite similar. Indeed, both rely on the same mechanism for initial recombination suppression: a ``lucky'' inversion, i.e. one with less deleterious mutations than the population average, encompassing the sex-determination locus, is initially selected. However, as it doesn't recombine, it will quickly accumulate deleterious mutations lowering its fitness. And it's at this point the models diverge: according to Lenormand & Roze (2022), nascent dosage compensation not only limits the deleterious effects on fitness by the ongoing degeneration, but it actually opposes recombination restoration as this would lead gene expression away from the optimum that has been reached. On the other hand, in the model by Jay et al. (2022), no additional ingredient is required: they argue that once an inversion had been fixed, reversions that restore recombination are extremely unlikely.

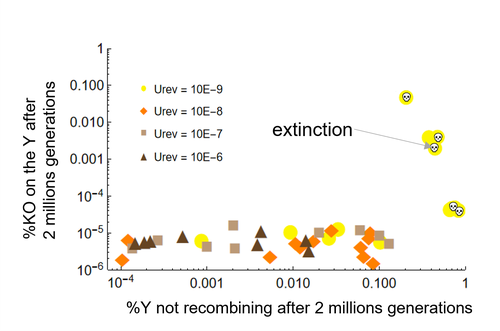

This is what Lenormand & Roze (2024) now call a ``constraint'': in Jay et al.'s model, recombination restoration is impossible for mechanistic reasons. Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue such constraints cannot explain long-term recombination suppression. Instead, a mechanism should evolve to limit the negative fitness effects of recombination arrest, otherwise recombination is either restored, or the population goes extinct due to a dramatic drop in the fitness of the heterogametic sex. These two arguments work together: given the huge fitness cost of the lack of ongoing degeneration of the non-recombining Y, in the absence of compensatory mechanisms, there is a very strong selection for the restoration of recombination, so that even when restoration a priori is orders of magnitude less likely than inversion (leading to recombination suppression), it will eventually happen.

One way the negative fitness effects of recombination suppression can be limited, is the way the authors propose in their own model: dosage compensation evolves through regulatory evolution right at the start of recombination suppression. This changes our classical, simplistic view that dosage compensation evolves in response to degeneration: rather, Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue, that degeneration can only happen when dosage compensation is effective.

The reasoning is convincing and exposes the difference between the models to readers without a firm background in mathematical modelling. Although Lenormand & Roze (2024) target the "constraint theory", it seems likely that other theories for the maintenance of recombination suppression that don't imply the compensation of early degeneration are subject to the same criticism. Indeed, they mention the widely-cited "sexual antagonism" theory, in which mutations with a positive effect in males but a negative in females will select for recombination suppression that will link them to the sex-determining gene on the Y. However, once degeneration starts, the sexually-antagonistic benefits should be huge to overcome the negative effects of degeneration, and it's unlikely they'll be large enough.

A convincing argument by Lenormand & Roze (2024) is that there are many ways recombination could be restored, allowing to circumvent the possible constraints that might be associated with reverting an inversion. First, reversions don't have to be exact to restore recombination. Second, the sex-determining locus can be transposed to another chromosome pair, or an entirely new sex-determining locus might evolve, leading to sex-chromosome turnover which has effectively been observed in several groups.

These modelling studies raise important questions that need to be addressed with both theoretical and empirical work. First, is the regulatory hypothesis proposed by Lenormand & Roze (2022) the only plausible mechanism for the maintenance of long-term recombination suppression? The female- and male-specific trans regulators of gene expression that are required for this model, are they readily available or do they need to evolve first? Both theoretical work and empirical studies of nascent sex chromosomes will help to answer these questions. However, nascent sex chromosomes are difficult to detect and dosage compensation is difficult to reveal.

Second, how many species today actually have "stable" recombination suppression? Maybe many species are in a transient phase, with different populations having different inversions that are either on their way to being fixed or starting to get counterselected. The models have now shown us some possibilities qualitatively but can they actually be quantified to be able to fit the data and to predict whether an observed case of recombination suppression is transient or stable?

The debate will continue, and we need the active contribution of theoretical biologists to help clarify the underlying hypotheses of the proposed mechanisms.

Conflict of interest statement: I did co-author a manuscript with D. Roze in 2023, but do not consider this a conflict of interest. The manuscript is the product of discussions that have taken place in a large consortium mainly in 2019. It furthermore deals with an entirely different topic of evolutionary biology.

References

Jay P, Tezenas E, Véber A, and Giraud T. (2022) Sheltering of deleterious mutations explains the stepwise extension of recombination suppression on sex chromosomes and other supergenes. PLoS Biol.;20:e3001698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001698

Lenormand T and Roze D. (2022) Y recombination arrest and degeneration in the absence of sexual dimorphism. Science;375:663-6. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj1813

Lenormand T and Roze D. (2024) Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes? bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.17.528909