GONZALEZ-VOYER Alejandro

- Evolutionary Ecology, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México, Mexico

- Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Life History, Macroevolution, Sexual Selection, Speciation

- recommender

Recommendations: 2

Reviews: 0

Recommendations: 2

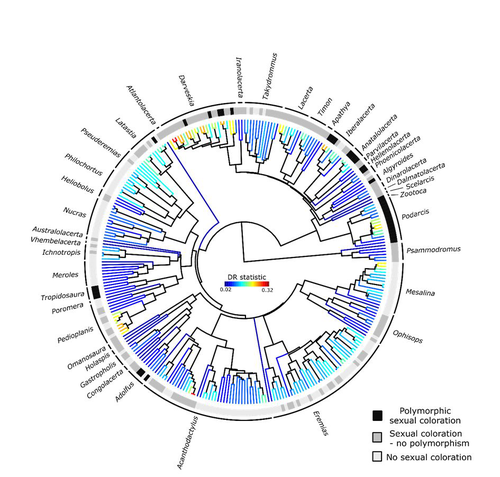

Color polymorphism and conspicuousness do not increase speciation rates in Lacertids

Colour polymorphism does not increase diversification rates in lizards

Recommended by Alejandro Gonzalez-Voyer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe striking differences in species richness among lineages in the Tree of Life have long attracted much research interest. In particular, researchers have asked whether certain traits are associated with greater diversification, with a particular focus on traits under sexual selection given their direct link to mating isolation.

Polymorphism, defined as the presence of co-occurring, heritable morphs within a population, has been proposed to influence diversification rates although the effect has been proposed as both promoting or alternatively impeding speciation. The effect of polymorphism may be positive, that is facilitating speciation if polymorphism allows to broaden the ecological niche, thus enabling range expansion, or enabling maintenance of populations in variable environments. Specialized ectomorphs have been observed in several species (e.g. Kusche et al. 2015, Lattanzio and Miles 2016, Whitney et al. 2018, Scali et al. 2016). Polymorphism may also facilitate speciation if a morph is lost during the colonization of a novel area or niche, resulting in rapid divergence of the remaining morphs and reproductive isolation from the ancestral population, known as the morph speciation hypothesis (West-Eberhard 1986, Corl et al. 2010). On the other hand, polymorphism may hamper speciation through disassortative maintaining by morph, which may maintain the polymorphism through the speciation process (Jamie and Meier 2020). An example of such a process is Heliconius numata where disassortative mate preferences based on color hampers ecological speciation (Chouteau et al. 2017). Previous evidence in birds and lizards suggests polymorphism favors diversification (Corl et al. 2010b, 2012, Hugall and Stuart-Fox 2012, Brock et al. 2021).

Here, de Solan et al. (2023) test the effect of polymorphism on diversification in Lacertidae, a family of lizards containing more than 300 species distributed across Europe, Africa and Asia. The group offers a good model system to test the effect of polymorphism on speciation as it contains several species with colour polymorphism, sometimes present in both sexes but restricted to males when present in the flank. Using coloration data from the literature as well as photographs of live specimens for 295 species the authors tested whether the presence of polymorphism is associated with higher diversification rates.

While undertaking their project, another group independently tackled the same question (Brock et al. 2021), using the same model system but coming to very different conclusions. Therefore, de Solan et al. (2023) decided to also contrast their results with those of Brock et al. (2021) to determine the factors responsible for the contrasting results of both studies. The latter I consider one of the strengths of the work, given the careful re-analyses to determine the causes of the discrepancies between both studies. De Solan et al. (2023) found no association between the presence of polymorphism and diversification rates, even though they used different analytical approaches. Thus, this study is interesting as it provides results that do not support a positive effect of polymorphism on species richness. The use of a phylogeny with more limited species sampling (García-Porta et al. 2019) implied that the authors had to manually add 75 species, of which 17 were added to the tree based on information from previously published trees and 68 were added at random locations within the genus. To control for potential biases the authors repeated the analyses using a sample of trees with the imputed taxa, results were broadly concordant across the set of trees. The careful re-analysis contrasting Brock et al. (2021) and de Solan et al. (2023) results suggests the difference is mainly due to a difference in how species were coded as presenting polymorphism, which differed between the two studies, as well as a difference in the package version used to run the state-dependent diversification models. Interestingly non-parametric analyses yielded similar results across both datasets.

References

Brock, K.M., McTavish, E.J., Edwards, D.L. 2021. Colour polymorphism is a driver of diversification in the lizard family Lacertidae. Systematic Biology. 71: 24-39. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syab046

Chouteau, M., Llaurens, V., Piron-Prunier, F., Joron, M. 2017. Polymorphism at a mimicry supergene maintained by opposing frequency-dependent selection pressures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114: 8325-8329. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702482114

Corl, A., Davis, A.R., Kuchta, S.R., Comendant, T., Sinervo, B. 2010a. Alternative mating strategies and the evolution of sexual dimorphism in the side-blotched lizard, Uta stansburiana: a population-level comparative analysis. Evolution. 64: 79-96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00791.x

Corl, A., Davis, A.R., Kuchta, S.R., Sinervo, B. 2010b. Selective loss of polymorphic mating types is associated with rapid phenotypic evolution during morphic speciation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107: 4254-4259. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0909480107

Corl, A., Lancaster, L.T., Sinervo, B. 2012. Rapid formation of reproductive isolation between two populations of side-blotched lizards, Uta stansburiana. Copeia. 2012: 593-602. https://doi.org/10.1643/CH-11-166

Garcia-Porta, J., Irisarri, I., Kirchner, M. et al. 2019. Environmental temperatures shape thermal physiology as well as diversification and genome-wide substitution rates in lizards. Nature Communications. 10: 4077. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11943-x

Hugall, A.F., Stuart-Fox, D. 2012. Accelerated speciation in colour-polymorphic birds. Nature. 485: 631-634. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11050

Jamie, G.A. and Meier, J.I. 2020. The persistence of polymorphisms across species radiations. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 35: 795-808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.04.007

Kusche, H., Elmer, K.R., Meyer, A. 2015. Sympatric ecological divergence associated with a colour polymorphism. BMC Biology, 13: 82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-015-0192-7

Lattanzio, M.S. and Miles, D.B. 2016. Trophic niche divergence among colour morphs that exhibit alternative mating tactics. Royal Society Open Science. 3: 150531. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150531

Scali, S., Sacchi, R., Mangiacotti, M., Pupin, F., Gentilli, A., Zucchi, C. Scannolo, M., Pavesi, M., Zuffi, M.A.L. 2016. Does a polymorphic species have a ‘polymorphic’ diet? A case study from a lacertid lizard. Biologcial Journal of the Linnean Society. 117: 492-502. https://doi.org/10.1111/bij.12652

de Solan T, Sinervo B, Geniez P, David P, Crochet P-A (2023) Colour polymorphism and conspicuousness do not increase speciation rates in Lacertids. bioRxiv, 2023.02.15.528678, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.15.528678

West-Eberhard, M.J. 1986. Alternative adaptations, speciation, and phylogeny (A review). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 83: 1388-1392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.83.5.1388

Whitney, J.L., Donahue, M.J., Karl, S.A. 2018. Niche divergence along a fine-scale ecological gradient in sympatric colour morphs of a coral reef fish. Ecosphere. 9: e02015. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2015

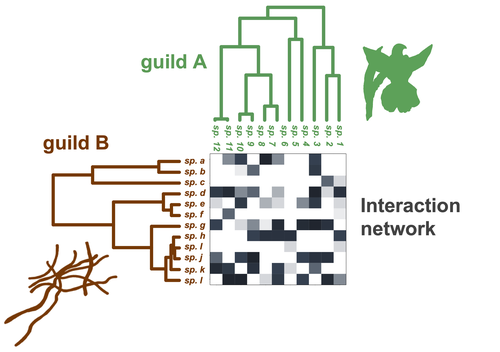

Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks

Testing for phylogenetic signal in species interaction networks

Recommended by Alejandro Gonzalez-Voyer based on reviews by Joaquin Calatayud and Thomas GuillermeSpecies are immersed within communities in which they interact mutualistically, as in pollination or seed dispersal, or nonreciprocally, such as in predation or parasitism, with other species and these interactions play a paramount role in shaping biodiversity (Bascompte and Jordano 2013). Researchers have become increasingly interested in the processes that shape these interactions and how these influence community structure and responses to disturbances. Species interactions are often described using bipartite interaction networks and one important question is how the evolutionary history of the species involved influences the network, including whether there is phylogenetic signal in interactions, in other words whether closely related species interact with other closely related species (Bascompte and Jordano 2013, Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022). To address this question different approaches, correlative and model-based, have been developed to test for phylogenetic signal in interactions, although comparative analyses of the performance of these different metrics are lacking. In their article Perez-Lamarque et al. (2022) set out to test the statistical performance of two widely-used methods, Mantel tests and Phylogenetic Bipartite Linear Models (PBLM; Ives and Godfray 2006) using simulations. Phylogenetic signal is measured as the degree to which distance to the nearest common ancestor predicts the observed similarity in trait values among species. In species interaction networks, the data are actually the between-species dissimilarity among interacting species (Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022), and typical approaches to test for phylogenetic signal cannot be used. However, the Mantel test provides a useful means of analyzing the correlation between two distance matrices, the between-species phylogenetic distance and the between-species dissimilarity in interactions. The PBLM approach, on the other hand, assumes that interactions between species are influenced by unobserved traits that evolve along the phylogenies following a given phenotypic evolution model and the parameters of this model are interpreted in terms of phylogenetic signal (Ives and Godfray 2006). Perez-Lamarque et al (2022) found that the model-based PBLM approach has a high type-I error rate, in other words it often detected phylogenetic signal when there was none. The simple Mantel test was found to present a low type-I error rate and moderate statistical power. However, it tended to overestimate the degree to which species interact with dissimilar partners. In addition to the aforementioned analyses, the authors also tested whether the simple Mantel test was able to detect phylogenetic signal in interactions among species within a given clade in the phylogeny, as phylogenetic signal in species interactions may be localized within specific clades. The article concludes with general guidelines for users wishing to test phylogenetic signal in their interaction networks and illustrates them with an example of an orchid-mycorrhizal fungus network from the oceanic island of La Réunion (Martos et al 2012). This broadly accessible article provides a valuable analysis of the performance of tests of phylogenetic signal in interaction networks enabling users to make informed choices of the analytical methods they wish to employ, and provide useful and detailed guidelines. Therefore, the work should be of broad interest to researchers studying species interactions.

References

Bascompte J, Jordano P (2013) Mutualistic Networks. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400848720

Ives AR, Godfray HCJ (2006) Phylogenetic Analysis of Trophic Associations. The American Naturalist, 168, E1–E14. https://doi.org/10.1086/505157

Martos F, Munoz F, Pailler T, Kottke I, Gonneau C, Selosse M-A (2012) The role of epiphytism in architecture and evolutionary constraint within mycorrhizal networks of tropical orchids. Molecular Ecology, 21, 5098–5109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05692.x

Perez-Lamarque B, Maliet O, Pichon B, Selosse M-A, Martos F, Morlon H (2022) Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks. bioRxiv, 2021.08.30.458192, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.30.458192