HARTFIELD Matthew

- Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex

- recommender

Recommendation: 1

Reviews: 0

Recommendation: 1

How does the mode of evolutionary divergence affect reproductive isolation?

A general model of fitness effects following hybridisation

Recommended by Matthew Hartfield based on reviews by Luis-Miguel Chevin and Juan LiStudying the effects of speciation, hybridisation, and evolutionary outcomes following reproduction from divergent populations is a major research area in evolutionary genetics [1]. There are two phenomena that have been the focus of contemporary research. First, a classic concept is the formation of ‘Bateson-Dobzhansky-Muller’ incompatibilities (BDMi) [2–4] that negatively affect hybrid fitness. Here, two diverging populations accumulate mutations over time that are unique to that subpopulation. If they subsequently meet, then these mutations might negatively interact, leading to a loss in fitness or even a complete lack of reproduction. BDMi formation can be complex, involving multiple genes and the fitness changes can depend on the direction of introgression [5]. Second, such secondary contact can instead lead to heterosis, where offspring are fitter than their parental progenitors [6].

Understanding which outcomes are likely to arise require one to know the potential fitness effects of mutations underlying reproductive isolation, to determine whether they are likely to reduce or enhance fitness when hybrids are formed. This is far from an easy task, as it requires one to track mutations at several loci, along with their effects, across a fitness landscape.

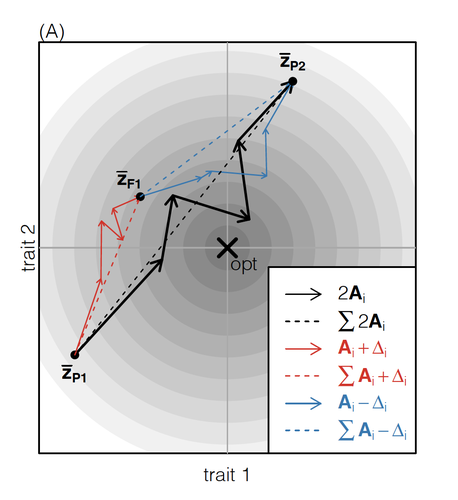

The work of De Sanctis et al. [7] neatly fills in this knowledge gap, by creating a general mathematical framework for describing the consequences of a cross from two divergent populations. The derivations are based on Fisher’s Geometric Model, which is widely used to quantify selection acting on a general fitness landscape that is affected by several biological traits [8,9], and has previously been used in theoretical studies of hybridisation [10–12]. By doing so, they are able to decompose how divergence at multiple loci affects offspring fitness through both additive and dominance effects.

A key result arising from their analyses is demonstrating how offspring fitness can be captured by two main functions. The first one is the ‘net effect of evolutionary change’ that, broadly defined, measures how phenotypically divergent two populations are. The second is the ‘total amount of evolutionary change’, which reflects how many mutations contribute to divergence and the effect sizes captured by each of them. The authors illustrate these measurements using simulations covering different scenarios, demonstrating how different parental states can lead to similar fitness outcomes. They also propose experimental methods to measure the underlying mutational effects.

This study neatly demonstrates how complex genetic phenomena underlying hybridisation can be captured using fairly simple mathematical formulae. This powerful approach will thus open the door for future research to investigate hybridisation in more detail, whether it is by expanding on these theoretical models or using the elegant outcomes to quantify fitness effects in experiments.

References

1. Coyne JA, Orr HA. Speciation. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 2004.

2. Bateson W, Seward A. Darwin and modern science. Heredity and variation in modern lights. 1909;85: 101. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511693953.007

3. Dobzhansky T. Genetics and the Origin of Species. Columbia university press; 1937.

4. Muller HJ. Isolating mechanisms, evolution and temperature. Biol Symp. 1942;6: 71-125.

5. Fraïsse C, Elderfield JAD, Welch JJ. The genetics of speciation: are complex incompatibilities easier to evolve? J Evol Biol. 2014;27: 688-699. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12339

6. Birchler JA, Yao H, Chudalayandi S, Vaiman D, Veitia RA. Heterosis. The Plant Cell. 2010;22: 2105-2112. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.110.076133

7. De Sanctis B, Schneemann H, Welch JJ. How does the mode of evolutionary divergence affect reproductive isolation? bioRxiv. 2022. 2022.03.08.483443 version 4. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.08.483443

8. Fisher RA. The genetical theory of natural selection. Oxford: The Clarendon Press; 1930. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.27468

9. Tenaillon O. The Utility of Fisher's Geometric Model in Evolutionary Genetics. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2014;45: 179-201. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-120213-091846

10. Barton NH. The role of hybridization in evolution. Molecular Ecology. 2001;10: 551-568. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01216.x

11. Chevin L-M, Decorzent G, Lenormand T. Niche Dimensionality and The Genetics of Ecological Speciation. Evolution. 2014;68: 1244-1256. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12346

12. Fraïsse C, Gunnarsson PA, Roze D, Bierne N, Welch JJ. The genetics of speciation: Insights from Fisher's geometric model. Evolution. 2016;70: 1450-1464. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12968