Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▼ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

16 Dec 2022

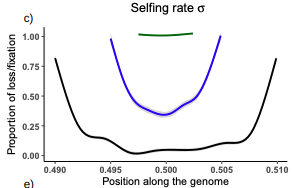

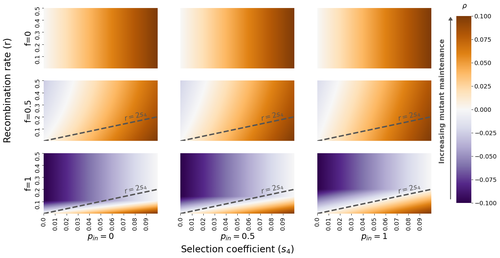

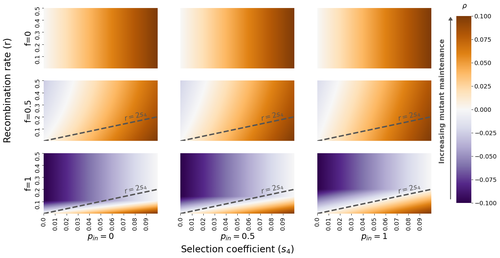

Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depressionDiala Abu Awad, Donald Waller https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.473022Pseudo-overdominance: how linkage and selection can interact and oppose to purging of deleterious mutations.Recommended by Sylvain Glémin based on reviews by Yaniv Brandvain, Lei Zhao and 1 anonymous reviewerMost mutations affecting fitness are deleterious and they have many evolutionary consequences. The dynamics and consequences of deleterious mutations are a long-standing question in evolutionary biology and a strong theoretical background has already been developed, for example, to predict the mutation load, inbreeding depression or background selection. One of the classical results is that inbreeding helps purge partially recessive deleterious mutations by exposing them to selection in homozygotes. However, this mainly results from single-locus considerations. When interactions among several, more or less linked, deleterious mutations are taken into account, peculiar dynamics can emerge. One of them, called pseudo-overdominance (POD), corresponds to the maintenance in a population of two (or more) haplotype blocks composed of several recessive deleterious mutations in repulsion that mimics overdominance. Indeed, homozygote individuals for one of the haplotype blocks expose many deleterious mutations to selection whereas they are reciprocally masked in heterozygotes, leading to higher fitness of heterozygotes compared to both homozygotes. A related process, called associative overdominance (AOD) is the effect of such deleterious alleles in repulsion on the linked neutral variation that can be increased by AOD. Although this possibility has been recognized for a long time (Otha and Kimura 1969), it has been mainly considered an anecdotal process. Recently, both theoretical (Zhao and Charlesworth 2016) and genomic analyses (Gilbert et al. 2020) have renewed interest in such a process, suggesting that it could be important in weakly recombining regions of a genome. Donald Waller (2021) - one of the co-authors of the current work - also recently proposed that POD could be quantitatively important with broad implications, and could resolve some unexplained observations such as the maintenance of inbreeding depression in highly selfing species. Yet, a proper theoretical framework analysing the effect of inbreeding on POD was lacking. In this theoretical work, Diala Abu Awad and Donald Waller (2022) addressed this question through an elegant combination of analytical predictions and intensive multilocus simulations. They determined the conditions under which POD can be maintained and how long it could resist erosion by recombination, which removes the negative association between deleterious alleles (repulsion) at the core of the mechanism. They showed that under tight linkage, POD regions can persist for a long time and generate substantial segregating load and inbreeding depression, even under inbreeding, so opposing (for a while) to the purging effect. They also showed that background selection can affect the genomic structure of POD regions by rapidly erasing weak POD regions but maintaining strong POD regions (i.e with many tightly linked deleterious alleles). These results have several implications. They can explain the maintenance of inbreeding depression despite inbreeding (as anticipated by Waller 2021), which has implications for the evolution of mating systems. If POD can hardly emerge under high selfing, it can persist from an outcrossing ancestor long after the transition towards a higher selfing rate and could explain the maintenance of mixed mating systems(which is possible with true overdominance, see Uyenoyama and Waller 1991). The results also have implications for genomic analyses, pointing to regions of low or no recombination where POD could be maintained, generating both higher diversity and heterozygosity than expected and variance in fitness. As structural variations are likely widespread in genomes with possible effects on suppressing recombination (Mérot et al. 2020), POD regions should be checked more carefully in genomic analyses (see also Gilbert et al. 2020). Overall, this work should stimulate new theoretical and empirical studies, especially to assess how quantitatively strong and widespread POD can be. It also stresses the importance of properly considering genetic linkage genome-wide, and so the role of recombination landscapes in determining patterns of diversity and fitness effects. References

Awad DA, Waller D (2022) Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depression. bioRxiv, 2021.12.16.473022, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.473022 Gilbert KJ, Pouyet F, Excoffier L, Peischl S (2020) Transition from Background Selection to Associative Overdominance Promotes Diversity in Regions of Low Recombination. Current Biology, 30, 101-107.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.11.063 Mérot C, Oomen RA, Tigano A, Wellenreuther M (2020) A Roadmap for Understanding the Evolutionary Significance of Structural Genomic Variation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35, 561–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.03.002 Ohta T, Kimura M (1969) Linkage disequilibrium at steady state determined by random genetic drift and recurrent mutation. Genetics, 63, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/63.1.229 Uyenoyama MK, Waller DM (1991) Coevolution of self-fertilization and inbreeding depression II. Symmetric overdominance in viability. Theoretical Population Biology, 40, 47–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(91)90046-I Waller DM (2021) Addressing Darwin’s dilemma: Can pseudo-overdominance explain persistent inbreeding depression and load? Evolution, 75, 779–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.14189 Zhao L, Charlesworth B (2016) Resolving the Conflict Between Associative Overdominance and Background Selection. Genetics, 203, 1315–1334. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.116.188912 | Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depression | Diala Abu Awad, Donald Waller | <p style="text-align: justify;">Classical models that ignore linkage predict that deleterious recessive mutations should purge or fix within inbred populations, yet inbred populations often retain moderate to high segregating load. True overdomina... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Sylvain Glémin | 2022-01-04 12:15:35 | View | |

21 Nov 2018

Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infectionFrederic Bertels, Karin J Metzner, Roland R Regoes https://doi.org/10.1101/168260Is convergence an evidence for positive selection?Recommended by Guillaume Achaz based on reviews by Jeffrey Townsend and 1 anonymous reviewerThe preprint by Bertels et al. [1] reports an interesting application of the well-accepted idea that positively selected traits (here variants) can appear several times independently; think about the textbook examples of flight capacity. Hence, the authors assume that reciprocally convergence implies positive selection. The methodology becomes then, in principle, straightforward as one can simply count variants in independent datasets to detect convergent mutations. References [1] Bertels, F., Metzner, K. J., & Regoes R. R. (2018). Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infection. BioRxiv, 168260, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/168260 | Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infection | Frederic Bertels, Karin J Metzner, Roland R Regoes | <p>Convergent evolution describes the process of different populations acquiring similar phenotypes or genotypes. Complex organisms with large genomes only rarely and only under very strong selection converge to the same genotype. In contrast, ind... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Guillaume Achaz | 2017-07-26 08:39:17 | View | |

18 Jan 2023

The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfingEmilie Tezenas, Tatiana Giraud, Amandine Veber, Sylvain Billiard https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.07.511119Maintenance of deleterious mutations and recombination suppression near mating-type loci under selfingRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe causes and consequences of the evolution of sexual reproduction are a major topic in evolutionary biology. With advances in sequencing technology, it becomes possible to compare sexual chromosomes across species and infer the neutral and selective processes shaping polymorphism at these chromosomes. Most sex and mating-type chromosomes exhibit an absence of recombination in large genomic regions around the animal, plant or fungal sex-determining genes. This suppression of recombination likely occurred in several time steps generating stepwise increasing genomic regions starting around the sex-determining genes. This mechanism generates so-called evolutionary strata of differentiation between sex chromosomes (Nicolas et al., 2004, Bergero and Charlesworth, 2009, Hartmann et al. 2021). The evolution of extended regions of recombination suppression is also documented on mating-type chromosomes in fungi (Hartmann et al., 2021) and around supergenes (Yan et al., 2020, Jay et al., 2021). The exact reason and evolutionary mechanisms for this phenomenon are still, however, debated. Two hypotheses are proposed: 1) sexual antagonism (Charlesworth et al., 2005), which, nevertheless, does explain the observed occurrence of the evolutionary strata, and 2) the sheltering of deleterious alleles by inversions carrying a lower load than average in the population (Charlesworth and Wall, 1999, Antonovics and Abrams, 2004). In the latter, the mechanism is as follows. A genetic inversion or a suppressor of recombination in cis may exhibit some overdominance behaviour. The inversion exhibiting less recessive deleterious mutations (compared to others at the same locus) may increase in frequency, before at higher frequency occurring at the homozygous state, expressing its genetic load. However, the inversion may never be at the homozygous state if it is genetically linked to a gene in a permanently heterozygous state. The inversion can then be advantageous and may reach fixation at the sex chromosome (Charlesworth and Wall, 1999, Antonovics and Abrams, 2004, Jay et al., 2022). These selective mechanisms promote thus the suppression of recombination around the sex-determining gene, and recessive deleterious mutations are permanently sheltered. This hypothesis is corroborated by the sheltering of deleterious mutations observed around loci under balancing selection (Llaurens et al. 2009, Lenz et al. 2016) and around mating-type genes in fungi and supergenes (Jay et al. 2021, Jay et al., 2022). In this present theoretical study, Tezenas et al. (2022) analyse how linkage to a necessarily heterozygous fungal mating type locus influences the persistence/extinction time of a new mutation at a second selected locus. This mutation can either be deleterious and recessive, or overdominant. There is arbitrary linkage between the two loci, and sexual reproduction occurs either between 1) gametes of different individuals (outcrossing), or 2) by selfing with gametes originating from the same (intra-tetrad) or different (inter-tetrad) tetrads produced by that individual. Note, here, that the mating-type gene does not prevent selfing. The authors study the initial stochastic dynamics of the mutation using a multi-type branching process (and simulations when analytical results cannot be obtained) to compute the extinction time of the deleterious mutation. The main result is that the presence of a mating-type locus always decreases the purging probability and increases the purging time of the mutations under selfing. Ultimately, deleterious mutations can indeed accumulate near the mating-type locus over evolutionary time scales. In a nutshell, high selfing or high intra-tetrad mating do increase the sheltering effect of the mating-type locus. In effect, the outcome of sheltering of deleterious mutations depends on two opposing mechanisms: 1) a higher selfing rate induces a greater production of homozygotes and an increased effect of the purging of deleterious mutations, while 2) a higher intra-tetrad selfing rate (or linkage with the mating-type locus) generates heterozygotes which have a small genetic load (and are favoured). The authors also show that rare events of extremely long maintenance of deleterious mutations can occur. The authors conclude by highlighting the manifold effect of selfing which reduces the effective population size and thus impairs the efficiency of selection and increases the mutational load, while also favouring the purge of deleterious homozygous mutations. Furthermore, this study emphasizes the importance of studying the maintenance and accumulation of deleterious mutations in the vicinity of heterozygous loci (e.g. under balancing selection) in selfing species. References Antonovics J, Abrams JY (2004) Intratetrad Mating and the Evolution of Linkage Relationships. Evolution, 58, 702–709. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00403.x Bergero R, Charlesworth D (2009) The evolution of restricted recombination in sex chromosomes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 24, 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.09.010 Charlesworth D, Morgan MT, Charlesworth B (1990) Inbreeding Depression, Genetic Load, and the Evolution of Outcrossing Rates in a Multilocus System with No Linkage. Evolution, 44, 1469–1489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb03839.x Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B, Marais G (2005) Steps in the evolution of heteromorphic sex chromosomes. Heredity, 95, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800697 Charlesworth B, Wall JD (1999) Inbreeding, heterozygote advantage and the evolution of neo–X and neo–Y sex chromosomes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 266, 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1999.0603 Hartmann FE, Duhamel M, Carpentier F, Hood ME, Foulongne-Oriol M, Silar P, Malagnac F, Grognet P, Giraud T (2021) Recombination suppression and evolutionary strata around mating-type loci in fungi: documenting patterns and understanding evolutionary and mechanistic causes. New Phytologist, 229, 2470–2491. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17039 Jay P, Chouteau M, Whibley A, Bastide H, Parrinello H, Llaurens V, Joron M (2021) Mutation load at a mimicry supergene sheds new light on the evolution of inversion polymorphisms. Nature Genetics, 53, 288–293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-00771-1 Jay P, Tezenas E, Véber A, Giraud T (2022) Sheltering of deleterious mutations explains the stepwise extension of recombination suppression on sex chromosomes and other supergenes. PLOS Biology, 20, e3001698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001698 Lenz TL, Spirin V, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR (2016) Excess of Deleterious Mutations around HLA Genes Reveals Evolutionary Cost of Balancing Selection. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 33, 2555–2564. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw127 Llaurens V, Gonthier L, Billiard S (2009) The Sheltered Genetic Load Linked to the S Locus in Plants: New Insights From Theoretical and Empirical Approaches in Sporophytic Self-Incompatibility. Genetics, 183, 1105–1118. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.109.102707 Nicolas M, Marais G, Hykelova V, Janousek B, Laporte V, Vyskot B, Mouchiroud D, Negrutiu I, Charlesworth D, Monéger F (2004) A Gradual Process of Recombination Restriction in the Evolutionary History of the Sex Chromosomes in Dioecious Plants. PLOS Biology, 3, e4. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0030004 Tezenas E, Giraud T, Véber A, Billiard S (2022) The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfing. bioRxiv, 2022.10.07.511119, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.07.511119 Yan Z, Martin SH, Gotzek D, Arsenault SV, Duchen P, Helleu Q, Riba-Grognuz O, Hunt BG, Salamin N, Shoemaker D, Ross KG, Keller L (2020) Evolution of a supergene that regulates a trans-species social polymorphism. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 240–249. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-1081-1 | The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfing | Emilie Tezenas, Tatiana Giraud, Amandine Veber, Sylvain Billiard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Large regions of suppressed recombination having extended over time occur in many organisms around genes involved in mating compatibility (sex-determining or mating-type genes). The sheltering of deleterious alleles... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Aurelien Tellier | 2022-10-10 13:50:30 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer