RUBIN Joshua Daniel

Recommendations: 0

Review: 1

Review: 1

mtDNA "Nomenclutter" and its Consequences on the Interpretation of Genetic Data

Resolving the clutter of naming “Eve’s” descendants

Recommended by Torsten Günther based on reviews by Nicole Huber, Joshua Daniel Rubin and 1 anonymous reviewerNature is complicated and humans often resort to categorization into simplified groups in order to comprehend and manage complex systems. The human mitochondrial genome and its phylogeny are quite complex. Many of those ~16600 base pairs mutated as humans spread across the planet and the resulting phylogeny can be used to illustrate many different aspects of human history and evolution. But it has too many branches and sub-branches to comprehend, which is why major lineages are considered haplogroups. On the highest level, these haplogroups receive capital letters which are then followed by integers and lowercase letters to designate a more fine-scale structure. This nomenclature even inspired semi-fictional literature, such as Bryan Sykes’ “The Seven Daughters of Eve” [1] from 2001 which includes fictional narratives for each of seven “clan mothers” representing seven major European haplogroups (e.g. Helene representing haplogroup H and Tara representing haplogroup T). But apart from categorizing things, humans also like to make exceptions to rules. For instance, not all haplogroup names consist only of letters and numbers but also special characters. And not everything seems logical or intuitive: the deepest split does not include haplogroup A but the most basal lineage is L0. The main letters also do not represent the same level of the tree structure, Sykes’ Katrine representing haplogroup K should not be considered a “daughter of Eve” but (at best) a granddaughter as K is a sub-haplogroup of U (represented by Ursula). This system and the number of haplogroups have not just reached a point where everything has become incredibly complicated despite supposedly simplifying categories. The inherent arbitrariness can also have serious effects on downstream analysis and the interpretation of results depending on how and on what level the authors of a specific study decide to group their individuals.

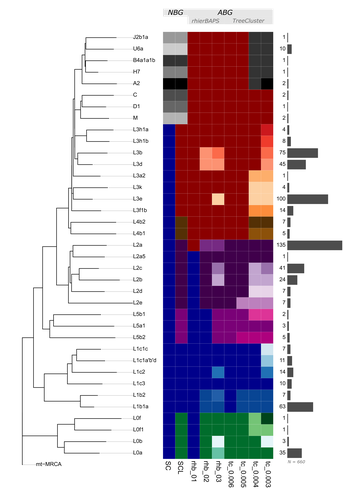

This situation of potential biases introduced through the choice of haplogroup groupings is the motivation for the study by Bajić, Schulmann and Nowick who are using the quite fitting term “nomenclutter” in their title [2]. They are raising an important issue in the inconsistencies introduced by the practice of somewhat arbitrary haplotype groupings which varies across studies and has no common standards in place making comparisons between studies virtually impossible. The study shows that the outcome of certain standard analyses and the interpretation of results are very sensitive to the decision on how to group the different haplotypes. This effect is especially pronounced for populations of African ancestry where the haplotype nomenclature would cut the phylogenetic tree at higher levels and the definition of different lineages is generally more coarse than for other populations.

But the authors go beyond pointing out this issue, they also suggest solutions. Instead of grouping sequences by their haplogroup code, one could use “algorithm-based groupings” based on the sequence similarity itself or cutting the phylogenetic tree at a common level of the hierarchy. The analysis of the authors shows that this reduces potential biases substantially. But even such groupings would not be without the influence of the user or researcher’s choices as different parameters have to be set to define the level at which groupings are conducted. The authors propose a neat solution, lifting this issue to be resolved during future updates of the mitochondrial haplogroup nomenclature and the phylogeny. Ideally, the research community could agree on centrally defined haplogroup grouping levels (called “macro-”, “meso-”, and “micro-haplogroups” by the authors) which would all represent different scales of events in human history (from global, continental to local). Classifications like that could be provided through central databases and the classifications could be added to commonly used tools for that purpose. If everyone used these groupings, studies would be a lot more comparable and more fine-scale investigations could still resort to the sequences and the tree itself to avoid all grouping.

The experts who reviewed the study have all highlighted its importance of pointing at a very relevant issue. It will take a community effort to improve practices and the current status of this research area. This study provides an important first step and it should be in everyone’s interest to resolve the “nomenclutter”.

References

1. Sykes B. (2001) The seven daughters of Eve: the science that reveals our genetic ancestry. 1st American ed. New York: Norton.

2. Bajić V, Schulmann VH, Nowick K. (2024) mtDNA “Nomenclutter” and its Consequences on the Interpretation of Genetic Data. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.19.567721