HUIJBEN Silvie

- Center for Evolution and Medicine, Arizona State University, TEMPE, United States of America

- Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory, Experimental Evolution

- recommender

Recommendation: 1

Review: 1

Recommendation: 1

Fitness costs and benefits in response to artificial artesunate selection in Plasmodium

The importance of understanding fitness costs associated with drug resistance throughout the life cycle of malaria parasites

Recommended by Silvie Huijben based on reviews by Sarah Reece and Marianna SzucsAntimalarial resistance is a major hurdle to malaria eradication efforts. The spread of drug resistance follows basic evolutionary principles, with competitive interactions between resistant and susceptible malaria strains being central to the fitness of resistant parasites. These competitive interactions can be used to design resistance management strategies, whereby a fitness cost of resistant parasites can be exploited through maintaining competitive suppression of the more fit drug-susceptible parasites. This can potentially be achieved using lower drug dosages or lower frequency of drug treatments. This approach has been demonstrated to work empirically in a rodent malaria model [1,2] and has been demonstrated to have clinical success in cancer treatments [3]. However, these resistance management approaches assume a fitness cost of the resistant pathogen, and, in the case of malaria parasites in general, and for artemisinin resistant parasites in particular, there is limited information on the presence of such fitness cost. The best suggestive evidence for the presence of fitness costs comes from the discontinuation of the use of the drug, which, in the case of chloroquine, was followed by a gradual drop in resistance frequency over the following decade [see e.g. 4,5]. However, with artemisinin derivative drugs still in use, alternative ways to study the presence of fitness costs need to be undertaken.

There are several good in vitro studies demonstrating artemisinin resistant parasites being competitively suppressed by wildtype parasites [see e.g. 6–9], however, these have the limitation that they will only be able to detect the fitness cost during the blood stage of the infection and in an artificial environment. So far, there have not been animal models that have thoroughly studied the presence of resistance fitness costs for artemisinin resistant parasites. Moreover, in these types of studies, the focus is mostly on the fitness cost as detected in the vertebrate host. However, malaria parasites spent a significant portion of their life cycle in the mosquito host, where fitness costs could also be expressed. Overall, it is the fitness over the entire life cycle of the parasite that would determine if and to what extent a reduction in resistance frequency would be observed when the use of a drug is stopped.

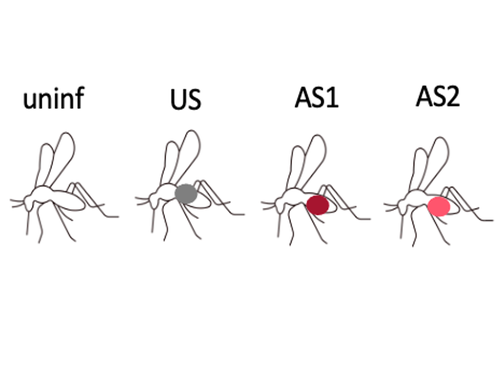

Here, Villa and colleagues present a study to quantify such fitness cost of artesunate-resistant parasites, not only in a vertebrate host, but also in the mosquito vector [10]. They used the underutilized model system of avian malaria species Plasmodium relictum in canaries. Villa and colleagues selected for several different resistance strains, which had a similar delayed clearance phenotype as observed in the field. Interestingly, they did not find evidence of a fitness cost in the vertebrate host. In fact, the resistant strains reached greater parasitaemia than the susceptible strains. From this set of experiments it is unclear whether this is an anomaly or a relevant result. Future work should establish this, though fitness benefits associated with drug resistance have been seen before in Leishmania parasites [11]. An important caveat to the present study is that the parasites were grown in the absence of competition and it is feasible that a cost is not detected when growing by themselves, but would become apparent when in competition. However, these types of experiments are technologically more challenging to perform as it would require an accurate quantification methodology able to distinguish based on one SNP. This problem has been circumvented by either using relative peak height in sanger sequencing [12], or via the likely more accurate route of pyrosequencing [7–9], though these methodologies only give relative frequencies rather than absolute densities.

The most interesting observation in the study by Villa et al is that the authors detected a fitness cost being played out in the mosquito vector, where the resistant strains had a decreased infectivity compared to the susceptible strain. This finding is important because 1) it demonstrates that the whole life cycle needs to be taken into account when understanding fitness costs, 2) resistance management strategies that are based on treatment within the vertebrate host may not have the intended effect if the cost does not play out in this host, and 3) it opens new research avenues to explore the possibility of exploiting fitness costs in mosquito vector. Future research should focus on incorporating these assays on fitness costs in mosquitoes, particularly for P. falciparum parasites. Additionally, it would be interesting to expand this work in a competitive environment, both in the vertebrate host as in the mosquito host. Finally, it would be important to establish the generalizability of such fitness cost in mosquitoes. If it is a significant factor, mathematical models could incorporate this effect in predictions on the spread of resistance.

References

[1] Huijben S, Bell AS, Sim DG, Tomasello D, Mideo N, Day T, et al. 2013. Aggressive chemotherapy and the selection of drug resistant pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 9(9): e1003578. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003578

[2] Huijben S, Nelson WA, Wargo AR, Sim DG, Drew DR, Read AF. 2010. Chemotherapy, within-host ecology and the fitness of drug-resistant malaria parasites. Evolution (N Y). 64(10): 2952-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01068.x

[3] Zhang J, Cunningham JJ, Brown JS, Gatenby RA. 2017. Integrating evolutionary dynamics into treatment of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01968-5

[4] Laufer MK, Takala-Harrison S, Dzinjalamala FK, Stine OC, Taylor TE, Plowe C v. 2010. Return of chloroquine-susceptible falciparum malaria in Malawi was a reexpansion of diverse susceptible parasites. J Infect Dis. 202(5): 801-808. https://doi.org/10.1086/655659

[5] Mharakurwa S, Matsena-Zingoni Z, Mudare N, Matimba C, Gara TX, Makuwaza A, et al. 2021. Steep rebound of chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum in Zimbabwe. J Infect Dis. 223(2): 306-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa368

[6] Tirrell AR, Vendrely KM, Checkley LA, Davis SZ, McDew-White M, Cheeseman IH, et al. 2019. Pairwise growth competitions identify relative fitness relationships among artemisinin resistant Plasmodium falciparum field isolates. Malar J. 18: 295. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-019-2934-4

[7] Hott A, Tucker MS, Casandra D, Sparks K, Kyle DE. 2015. Fitness of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother. 70(10): 2787-2796. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkv199

[8] Straimer J, Gnädig NF, Stokes BH, Ehrenberger M, Crane AA, Fidock DA. 2017. Plasmodium falciparum K13 mutations differentially impact ozonide susceptibility and parasite fitness in vitro. mBio. 8(2): e00172-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00172-17

[9] Nair S, Li X, Arya GA, McDew-White M, Ferrari M, Nosten F, et al. 2018. Fitness costs and the rapid spread of kelch13-C580Y substitutions conferring artemisinin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 62(9). https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00605-18

[10] Villa M, Berthomieu A, Rivero A. Fitness costs and benefits in response to artificial artesunate selection in Plasmodium. 2022. bioRxiv, 20220128478164, ver 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.28.478164

[11] Vanaerschot M, Decuypere S, Berg M, Roy S, Dujardin JC. 2013. Drug-resistant microorganisms with a higher fitness--can medicines boost pathogens? Crit Rev Microbiol. 39(4): 384-394. https://doi.org/10.3109/1040841X.2012.716818

[12] Hassett MR, Roepe PD. In vitro growth competition experiments that suggest consequences of the substandard artemisinin epidemic that may be accelerating drug resistance in P. falciparum malaria. 2021. PLoS One. 16(3): e0248057. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248057

Review: 1

An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila

Cancer and loneliness in Drosophila

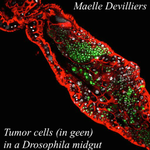

Recommended by Ana Rivero based on reviews by Ana Rivero and Silvie HuijbenDrosophila flies may not be perceived as a quintessentially social animal, particularly when compared to their eusocial hymenopteran cousins. Although they have no parental care, division of labour or subfertile caste, fruit flies nevertheless exhibit an array of social phenotypes that are potentially comparable to those of their highly social relatives. In the wild, Drosophila adults cluster around food resources where courtship, mating activity and oviposition occur. Recent work has shown not only that social interactions in these clusters condition many aspects of the behaviour and physiology of the flies [1] but also, and perhaps more unexpectedly, that social isolation has a negative impact on their fitness [2].

Many studies in humans point to the role of social isolation as a source of stress that can induce and accelerate disease progression. The ultimate proof of the connection between social interaction and disease is however mired in confounding variables and alternative explanations so the subject, though crucial, remains controversial. With a series of elegant experiments using Drosophila flies that develop an inducible form of intestinal cancer, Dawson et al [3] show that cancer progresses more rapidly in flies maintained in isolation than in flies maintained with other cancerous flies. Further, cancerous flies kept with non-cancerous flies, fare just as badly as when kept alone. Their experiments suggest that this is due to the combined effect of healthy flies avoiding contact with cancerous flies (even though this is a non-contagious disease), and of cancerous flies having higher quality interactions with other cancerous flies than with healthy ones. Perceived isolation is therefore as pernicious as real isolation when it comes to cancer progression in these flies. Like all good research, this study opens up as many questions as it answers, in particular the why and wherefores of the flies’ extraordinary social behaviour in the face of disease.

References

[1] Camiletti AL and Thompson GJ. 2016. Drosophila as a genetically tractable model for social insect behavior. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 4: 40. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2016.00040

[2] Ruan H and Wu C-F. 2008. Social interaction-mediated lifespan extension of Drosophila Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 105: 7506-7510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711127105

[3] Dawson E, Bailly T, Dos Santos J, Moreno C, Devilliers M, Maroni B, Sueur C, Casali A, Ujvari B, Thomas F, Montagne J, Mery F. 2017. An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila. BiorXiv, 143560, ver. 3 of 19th September 2017. doi: 10.1101/143560