Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▼ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

01 Jul 2022

Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fuscaKamil S. Jaron, Christina N. Hodson, Jacintha Ellers, Stuart JE Baird, Laura Ross https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.12.468426Pressing NGS data through the mill of Kmer spectra and allelic coverage ratios in order to scan reproductive modes in non-model speciesRecommended by Nicolas Bierne based on reviews by Paul Simion and 2 anonymous reviewersThe genomic revolution has given us access to inexpensive genetic data for any species. Simultaneously we have lost the ability to easily identify chimerism in samples or some unusual deviations from standard Mendelian genetics. Methods have been developed to identify sex chromosomes, characterise the ploidy, or understand the exact form of parthenogenesis from genomic data. However, we rarely consider that the tissues we extract DNA from could be a mixture of cells with different genotypes or karyotypes. This can nonetheless happen for a variety of (fascinating) reasons such as somatic chromosome elimination, transmissible cancer, or parental genome elimination. Without a dedicated analysis, it is very easy to miss it. In this preprint, Jaron et al. (2022) used an ingenious analysis of whole individual NGS data to test the hypothesis of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca. The authors suspected that a high fraction of the whole body of males is made of sperm in this species and if this species undergoes paternal genome elimination, we would expect that sperm would only contain maternally inherited chromosomes. Given the reference genome was highly fragmented, they developed a two-tissue model to analyse Kmer spectra and obtained confirmation that around one-third of the tissue was sperm in males. This allowed them to test whether coverage patterns were consistent with the species exhibiting paternal genome elimination. They combined their estimation of the fraction of haploid tissue with allele coverages in autosomes and the X chromosome to obtain support for a bias toward one parental allele, suggesting that all sperm carries the same parental haplotype. It could be the maternal or the paternal alleles, but paternal genome elimination is most compatible with the known biology of Arthropods. SNP calling was used to confirm conclusions based on the analysis of the raw pileups. I found this study to be a good example of how a clever analysis of Kmer spectra and allele coverages can provide information about unusual modes of reproduction in a species, even though it does not have a well-assembled genome yet. As advocated by the authors, routine inspection of Kmer spectra and allelic read-count distributions should be included in the best practice of NGS data analysis. They provide the method to identify paternal genome elimination but also the way to develop similar methods to detect another kind of genetic chimerism in the avalanche of sequence data produced nowadays. References Jaron KS, Hodson CN, Ellers J, Baird SJ, Ross L (2022) Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca. bioRxiv, 2021.11.12.468426, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.12.468426 | Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca | Kamil S. Jaron, Christina N. Hodson, Jacintha Ellers, Stuart JE Baird, Laura Ross | <p style="text-align: justify;">Paternal genome elimination (PGE) - a type of reproduction in which males inherit but fail to pass on their father’s genome - evolved independently in six to eight arthropod clades. Thousands of species, including s... | Genome Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Nicolas Bierne | 2021-11-18 00:09:43 | View | ||

04 Mar 2021

Simulation of bacterial populations with SLiMJean Cury, Benjamin C. Haller, Guillaume Achaz, and Flora Jay https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.28.316869Simulating bacterial evolution forward-in-timeRecommended by Frederic Bertels based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersJean Cury and colleagues (2021) have developed a protocol to simulate bacterial evolution in SLiM. In contrast to existing methods that depend on the coalescent, SLiM simulates evolution forward in time. SLiM has, up to now, mostly been used to simulate the evolution of eukaryotes (Haller and Messer 2019), but has been adapted here to simulate evolution in bacteria. Forward-in-time simulations are usually computationally very costly. To circumvent this issue, bacterial population sizes are scaled down. One would now expect results to become inaccurate, however, Cury et al. show that scaled-down forwards simulations provide very accurate results (similar to those provided by coalescent simulators) that are consistent with theoretical expectations. Simulations were analyzed and compared to existing methods in simple and slightly more complex scenarios where recombination affects evolution. In all scenarios, simulation results from coalescent methods (fastSimBac (De Maio and Wilson 2017), ms (Hudson 2002)) and scaled-down forwards simulations were very similar, which is very good news indeed. A biologist not aware of the complexities of forwards, backwards simulations and the coalescent, might now naïvely ask why another simulation method is needed if existing methods perform just as well. To address this question the manuscript closes with a very neat example of what exactly is possible with forwards simulations that cannot be achieved using existing methods. The situation modeled is the growth and evolution of a set of 50 bacteria that are randomly distributed on a petri dish. One side of the petri dish is covered in an antibiotic the other is antibiotic-free. Over time, the bacteria grow and acquire antibiotic resistance mutations until the entire artificial petri dish is covered with a bacterial lawn. This simulation demonstrates that it is possible to simulate extremely complex (e.g. real world) scenarios to, for example, assess whether certain phenomena are expected with our current understanding of bacterial evolution, or whether there are additional forces that need to be taken into account. Hence, forwards simulators could significantly help us to understand what current models can and cannot explain in evolutionary biology.

References Cury J, Haller BC, Achaz G, Jay F (2021) Simulation of bacterial populations with SLiM. bioRxiv, 2020.09.28.316869, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.28.316869 De Maio N, Wilson DJ (2017) The Bacterial Sequential Markov Coalescent. Genetics, 206, 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.116.198796 Haller BC, Messer PW (2019) SLiM 3: Forward Genetic Simulations Beyond the Wright–Fisher Model. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 36, 632–637. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy228 Hudson RR (2002) Generating samples under a Wright–Fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics, 18, 337–338. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/18.2.337 | Simulation of bacterial populations with SLiM | Jean Cury, Benjamin C. Haller, Guillaume Achaz, and Flora Jay | <p>Simulation of genomic data is a key tool in population genetics, yet, to date, there is no forward-in-time simulator of bacterial populations that is both computationally efficient and adaptable to a wide range of scenarios. Here we demonstrate... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics | Frederic Bertels | 2020-10-02 19:03:42 | View | |

17 Jun 2022

Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process?Claire Capdevielle Dulac, Romain Benoist, Sarah Paquet, Paul-André Calatayud, Julius Obonyo, Laure Kaiser, Florence Mougel https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.13.472356The potential evolutionary importance of low-frequency flexibility in reproductive modesRecommended by Christoph Haag based on reviews by Michael Lattorff and Jens BastOccasional events of asexual reproduction in otherwise sexual taxa have been documented since a long time. Accounts range from observations of offspring development from unfertilized eggs in Drosophila to rare offspring production by isolated females in lizards and birds (e.g., Stalker 1954, Watts et al 2006, Ryder et al. 2021). Many more such cases likely await documentation, as rare events are inherently difficult to observe. These rare events of asexual reproduction are often associated with low offspring fitness (“tychoparthenogenesis”), and have mostly been discarded in the evolutionary literature as reproductive accidents without evolutionary significance. Recently, however, there has been an increased interest in the details of evolutionary transitions from sexual to asexual reproduction (e.g., Archetti 2010, Neiman et al.2014, Lenormand et al. 2016), because these details may be key to understanding why successful transitions are rare, why they occur more frequently in some groups than in others, and why certain genetic mechanisms of ploidy maintenance or ploidy restoration are more often observed than others. In this context, the hypothesis has been formulated that regular or even obligate asexual reproduction may evolve from these rare events of asexual reproduction (e.g., Schwander et al. 2010). A new study by Capdevielle Dulac et al. (2022) now investigates this question in a parasitoid wasp, highlighting also the fact that what is considered rare or occasional may differ from one system to the next. The results show “rare” parthenogenetic production of diploid daughters occurring at variable frequencies (from zero to 2 %) in different laboratory strains, as well as in a natural population. They also demonstrate parthenogenetic production of female offspring in both virgin females and mated ones, as well as no reduced fecundity of parthenogenetically produced offspring. These findings suggest that parthenogenetic production of daughters, while still being rare, may be a more regular and less deleterious reproductive feature in this species than in other cases of occasional asexuality. Indeed, haplodiploid organisms, such as this parasitoid wasp have been hypothesized to facilitate evolutionary transitions to asexuality (Neimann et al. 2014, Van Der Kooi et al. 2017). First, in haploidiploid organisms, females are diploid and develop from normal, fertilized eggs, but males are haploid as they develop parthenogenetically from unfertilized eggs. This means that, in these species, fertilization is not necessarily needed to trigger development, thus removing one of the constraints for transitions to obligate asexuality (Engelstädter 2008, Vorburger 2014). Second, spermatogenesis in males occurs by a modified meiosis that skips the first meiotic division (e.g., Ferree et al. 2019). Haploidiploid organisms may thus have a potential route for an evolutionary transition to obligate parthenogenesis that is not available to organisms: The pathways for the modified meiosis may be re-used for oogenesis, which might result in unreduced, diploid eggs. Third, the particular species studied here regularly undergoes inbreeding by brother-sister mating within their hosts. Homozygosity, including at the sex determination locus (Engelstädter 2008), is therefore expected to have less negative effects in this species compared to many other, non-inbreeding haplodipoids (see also Little et al. 2017). This particular species may therefore be less affected by loss of heterozygosity, which occurs in a fashion similar to self-fertilization under many forms of non-clonal parthenogenesis. Indeed, the study also addresses the mechanisms underlying parthenogenesis in the species. Surprisingly, the authors find that parthenogenetically produced females are likely produced by two distinct genetic mechanisms. The first results in clonality (maintenance of the maternal genotype), whereas the second one results in a loss of heterozygosity towards the telomeres, likely due to crossovers occurring between the centromeres and the telomeres. Moreover, bacterial infections appear to affect the propensity of parthenogenesis but are unlikely the primary cause. Together, the finding suggests that parthenogenesis is a variable trait in the species, both in terms of frequency and mechanisms. It is not entirely clear to what degree this variation is heritable, but if it is, then these results constitute evidence for low-frequency existence of variable and heritable parthenogenesis phenotypes, that is, the raw material from which evolutionary transitions to more regular forms of parthenogenesis may occur.

References Archetti M (2010) Complementation, Genetic Conflict, and the Evolution of Sex and Recombination. Journal of Heredity, 101, S21–S33. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esq009 Capdevielle Dulac C, Benoist R, Paquet S, Calatayud P-A, Obonyo J, Kaiser L, Mougel F (2022) Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process? bioRxiv, 2021.12.13.472356, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.13.472356 Engelstädter J (2008) Constraints on the evolution of asexual reproduction. BioEssays, 30, 1138–1150. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.20833 Ferree PM, Aldrich JC, Jing XA, Norwood CT, Van Schaick MR, Cheema MS, Ausió J, Gowen BE (2019) Spermatogenesis in haploid males of the jewel wasp Nasonia vitripennis. Scientific Reports, 9, 12194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48332-9 van der Kooi CJ, Matthey-Doret C, Schwander T (2017) Evolution and comparative ecology of parthenogenesis in haplodiploid arthropods. Evolution Letters, 1, 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.30 Lenormand T, Engelstädter J, Johnston SE, Wijnker E, Haag CR (2016) Evolutionary mysteries in meiosis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371, 20160001. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0001 Little CJ, Chapuis M-P, Blondin L, Chapuis E, Jourdan-Pineau H (2017) Exploring the relationship between tychoparthenogenesis and inbreeding depression in the Desert Locust, Schistocerca gregaria. Ecology and Evolution, 7, 6003–6011. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3103 Neiman M, Sharbel TF, Schwander T (2014) Genetic causes of transitions from sexual reproduction to asexuality in plants and animals. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 27, 1346–1359. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12357 Ryder OA, Thomas S, Judson JM, Romanov MN, Dandekar S, Papp JC, Sidak-Loftis LC, Walker K, Stalis IH, Mace M, Steiner CC, Chemnick LG (2021) Facultative Parthenogenesis in California Condors. Journal of Heredity, 112, 569–574. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esab052 Schwander T, Vuilleumier S, Dubman J, Crespi BJ (2010) Positive feedback in the transition from sexual reproduction to parthenogenesis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277, 1435–1442. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.2113 Stalker HD (1954) Parthenogenesis in Drosophila. Genetics, 39, 4–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/39.1.4 Vorburger C (2014) Thelytoky and Sex Determination in the Hymenoptera: Mutual Constraints. Sexual Development, 8, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356508 Watts PC, Buley KR, Sanderson S, Boardman W, Ciofi C, Gibson R (2006) Parthenogenesis in Komodo dragons. Nature, 444, 1021–1022. https://doi.org/10.1038/4441021a | Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process? | Claire Capdevielle Dulac, Romain Benoist, Sarah Paquet, Paul-André Calatayud, Julius Obonyo, Laure Kaiser, Florence Mougel | <p style="text-align: justify;">Hymenopterans are haplodiploids and unlike most other Arthropods they do not possess sexual chromosomes. Sex determination typically happens via the ploidy of individuals: haploids become males and diploids become f... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Reproduction and Sex | Christoph Haag | 2021-12-16 15:25:16 | View | |

31 Jul 2017

Selection on morphological traits and fluctuating asymmetry by a fungal parasite in the yellow dung flyWolf U. Blanckenhorn 10.1101/136325Parasite-mediated selection promotes small body size in yellow dung fliesRecommended by Rodrigo Medel based on reviews by Rodrigo Medel and 1 anonymous reviewerBody size has long been considered as one of the most important organismic traits influencing demographical processes, population size, and evolution of life history strategies [1, 2]. While many studies have reported a selective advantage of large body size, the forces that determine small-sized organisms are less known, and reports of negative selection coefficients on body size are almost absent at present. This lack of knowledge is unfortunate as climate change and energy demands in stressful environments, among other factors, may produce new selection scenarios and unexpected selection surfaces [3]. In this manuscript, Blanckenhorn [4] reports on a potential explanation for the surprising 10% body size decrease observed in a Swiss population of yellow dung flies during 1993 - 2009. The author took advantage of a fungus outbreak in 2002 to assess the putative role of the fungus Entomopthora scatophagae, a specific parasite of adult yellow dung flies, as selective force acting upon host body size. His findings indicate that, as expected by sexual selection theory, large males experience a mating advantage. However, this positive sexual selection is opposed by a strong negative selection on male and female body size through the viability fitness component. This study provides the first evidence of parasite-mediated disadvantage of large adult body size in the field. While further experimental work is needed to elucidate the exact causes of body size reduction in the population, the author proposes a variation of the trade-off hypothesis raised by Rantala & Roff [5] that large-sized individuals face an immunity cost due to their high absolute energy demands in stressful environments. References [1] Peters RH. 1983. The ecological implications of body size. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [2] Schmidt-Nielsen K. 1984. Scaling: why is animal size so important? Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [3] Ohlberger J. 2013. Climate warming and ectotherm body size: from individual physiology to community ecology. Functional Ecology 27: 991-1001. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12098 [4] Blanckenhorn WU. 2017. Selection on morphological traits and fluctuating asymmetry by a fungal parasite in the yellow dung fly. bioRxiv 136325, ver. 2 of 29th June 2017. doi: 10.1101/136325 [5] Rantala MJ & Roff DA. 2005. An analysis of trade-offs in immune function, body size and development time in the Mediterranean field cricket, Gryllus bimaculatus. Functional Ecology 19: 323-330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2005.00979.x | Selection on morphological traits and fluctuating asymmetry by a fungal parasite in the yellow dung fly | Wolf U. Blanckenhorn | Evidence for selective disadvantages of large body size remains scarce in general. Previous phenomenological studies of the yellow dung fly *Scathophaga stercoraria* have demonstrated strong positive sexual and fecundity selection on male and fema... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Sexual Selection | Rodrigo Medel | Rodrigo Medel | 2017-05-10 11:16:26 | View |

02 Nov 2020

Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosisDavid Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265Temperature effects on virulence evolution of wMelPop Wolbachia in Drosophila melanogasterRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Shira Houwenhuyse and 3 anonymous reviewersMonnin et al. [1] here studied how Drosophila populations are affected when exposed to a high virulent endosymbiotic wMelPop Wolbachia strain and why virulent vertically transmitting endosymbionts persist in nature. This virulent wMelPop strain has been described to be a blocker of dengue and other arboviral infections in arthropod vector species, such as Aedes aegypti. Whereas it can thus function as a mutualistic symbiont, it here acts as an antagonist along the mutualism-antagonism continuum symbionts operate. The wMelPop strain is not a natural occurring strain in Drosophila melanogaster and thus the start of this experiment can be seen as a novel host-pathogen association. Through experimental evolution of 17 generations, the authors studied how high temperature affects wMelPop Wolbachia virulence and Drosophila melanogaster survival. The authors used Drosophila strains that were selected for late reproduction, given that this should favor evolution to a lower virulence. Assumptions for this hypothesis are not given in the manuscript here, but it can indeed be assumed that energy that is assimilated to symbiont tolerance instead of reproduction may lead to reduced virulence evolution. This has equally been suggested by Reyserhove et al. [2] in a dynamics energy budget model tailored to Daphnia magna virulence evolution upon a viral infection causing White fat Cell disease, reconstructing changing environments through time. References [1] Monnin, D., Kremer, N., Michaud, C., Villa, M., Henri, H., Desouhant, E. and Vavre, F. (2020) Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis. bioRxiv, 2020.04.26.062265, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265 | Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis | David Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre | <p>Evolutionary theory predicts that vertically transmitted symbionts are selected for low virulence, as their fitness is directly correlated to that of their host. In contrast with this prediction, the Wolbachia strain wMelPop drastically reduces... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Species interactions | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-04-29 19:16:56 | View | |

11 Oct 2022

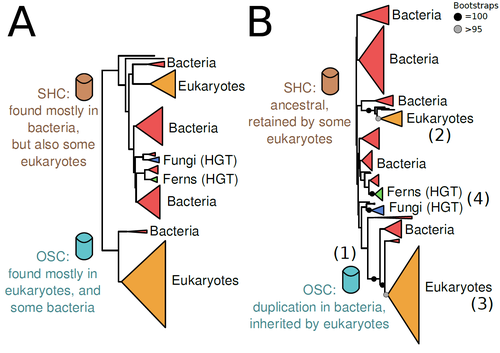

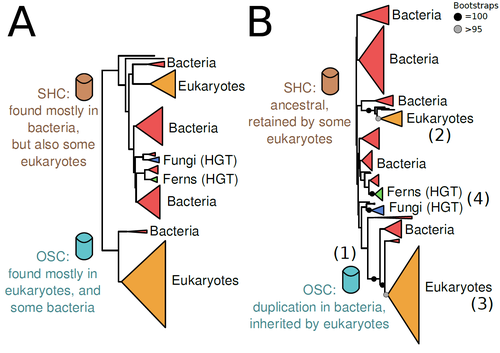

The Eukaryotic Last Common Ancestor Was Bifunctional for Hopanoid and Sterol ProductionWarren R Francis https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202004.0186.v5Gene family analysis suggests new evolutionary scenario for sterol and hopanoid biomarkersRecommended by Iker Irisarri based on reviews by Samuel Abalde, Denis Baurain and Jose Ramon Pardos-BlasSterols and hopanoids are sometimes used as biomarkers to infer the origin of certain groups of organisms. Traditionally, hopanoid-derived products in ancient rocks have been considered to indicate the presence of bacteria, whereas sterol derivatives have been considered to be exclusive to eukaryotes. However, a closer look at the topic reveals a rather complex distribution of either compound in both bacteria and eukaryotes. (1). The known biosynthetic pathways for sterols and hopanoids are similar but diverge at a critical step where two different enzymes are used: squalene-hopene cyclase (SHC) and oxidosqualene cyclase (OSC), the latter requiring oxygen. These two enzymes belong to the same gene family, whose complex evolutionary history is difficult to reconcile with the known species phylogeny. In this study (2), Dr. Warren R. Francis revisits the evolution of this gene family using an extended dataset with a broader taxonomic representation. In contrast to the traditional representation of the tree rooted between SHC and OSC paralogs (i.e., based on function), the author proposes that rooting the tree within bacterial SHCs and assuming a secondary origin of OSC is more parsimonious. This postulates SHC to be the ancestral function –retained in many extant bacteria and some eukaryotes– and OSC to have emerged later within bacteria –currently being mostly present in eukaryotes–. The reconstructed evolutionary history is arguably complex and can only be reconciled with the species' phylogeny by invoking many secondary losses. These losses are considered likely because many extant species acquire sterols and hopanoids by diet and lack one or both enzymes. Some cases of recent horizontal gene transfer are also proposed. In contrast to the dichotomy between bacterial SHCs and eukaryote OSCs, the new proposed scenario suggests that the eukaryote ancestor likely inherited both enzymes from bacteria and thus could be able to synthesize both sterols and hopanoids. Under this hypothesis, not only bacteria but also eukaryotes could be responsible for the hopane found in old rocks. This agrees with eukaryote fossils dating back to more than 1 billion years ago (3). Also, the observed increase of sterane levels in rocks ~600-700 million years old cannot be associated with the origin of eukaryotes, which is a much older event, but could rather reflect changes in atmospheric oxygen levels because oxygen is required for the synthesis of sterols by OSC. References 1. Santana-Molina C, Rivas-Marin E, Rojas AM, Devos DP (2020) Origin and Evolution of Polycyclic Triterpene Synthesis. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 37, 1925–1941. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa054 2. Francis WR (2022) The Eukaryotic Last Common Ancestor Was Bifunctional for Hopanoid and Sterol Production. Preprints, 2020040186, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202004.0186.v5 3. Butterfield NJ (2000) Bangiomorpha pubescens n. gen., n. sp.: implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity, and the Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes. Paleobiology, 26, 386–404. https://doi.org/10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0386:BPNGNS>2.0.CO;2 | The Eukaryotic Last Common Ancestor Was Bifunctional for Hopanoid and Sterol Production | Warren R Francis | <p>Steroid and hopanoid biomarkers can be found in ancient rocks and may give a glimpse of what life was present at that time. Sterols and hopanoids are produced by two related enzymes, though the evolutionary history of this protein family is com... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Molecular Evolution, Paleontology, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Iker Irisarri | 2021-01-13 16:03:29 | View | |

15 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichensSpribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al. 10.1126/science.aaf8287New partner at the core of macrolichen diversityRecommended by Enric Frago and Benoit FaconIt has long been known that most multicellular eukaryotes rely on microbial partners for a variety of functions including nutrition, immune reactions and defence against enemies. Lichens are probably the most popular example of a symbiosis involving a photosynthetic microorganism (an algae, a cyanobacteria or both) living embedded within the filaments of a fungus (usually an ascomycete). The latter is the backbone structure of the lichen, whereas the former provides photosynthetic products. Lichens are unique among symbioses because the structures the fungus and the photosynthetic microorganism form together do not resemble any of the two species living in isolation. Classic textbook examples like lichens are not often challenged and this is what Toby Spribille and his co-authors did with their paper published in July 2016 in Science [1]. This story started with the study of two species of macrolichens from the class of Lecanoromycetes that are commonly found in the mountains of Montana (US): Bryoria fremontii and B. tortuosa. For more than 90 years, these species have been known to differ in their chemical composition and colour, but studies performed so far failed in finding differences at the molecular level in both the mycobiont and the photobiont. These two species were therefore considered as nomenclatural synonyms, and the origin of their differences remained elusive. To solve this mystery, the authors of this work performed a transcriptome-wide analysis that, relative to previous studies, expanded the taxonomic range to all Fungi. This analysis revealed higher abundances of a previously unknown basidiomycete yeast from the genus Cyphobasidium in one of the lichen species, a pattern that was further confirmed by combining microscopy imaging and the fluorescent in situ hybridisation technique (FISH). Finding out that a previously unknown micro-organism changes the colour and the chemical composition of an organism is surprising but not new. For instance, bacterial symbionts are able to trigger colour changes in some insect species [2], and endophyte fungi are responsible for the production of defensive compounds in the leaves of several grasses [3]. The study by Spribille and his co-authors is fascinating because it demonstrates that Cyphobasidium yeasts have played a key role in the evolution and diversification of Lecanoromycetes, one of the most diverse classes of macrolichens. Indeed these basidiomycete yeasts were not only found in Bryoria but in 52 other lichen genera from all six continents, and these included 42 out of 56 genera in the family Parmeliaceae. Most of these sequences formed a highly supported monophyletic group, and a molecular clock revealed that the origin of many macrolichen groups occurred around the same time Cyphobasidium yeasts split from Cystobasidium, their nearest relatives. This newly discovered passenger is therefore an ancient inhabitant of lichens and has driven the evolution of this emblematic group of organisms. This study raises an important question on the stability of complex symbiotic partnerships. In intimate obligatory symbioses the evolutionary interests of both partners are often identical and what is good for one is also good for the other. This is the case of several insects that feed on poor diets like phloem and xylem sap, and which carry vertically-transmitted symbionts that provide essential nutrients. Molecular phylogenetic studies have repeatedly shown that in several insect groups transition to phloem or xylem feeding occurred at the same time these nutritional symbionts were acquired [4]. In lichens, an outstanding question is to know what was the key feature Cyphobasidium yeasts brought to the symbiosis. As suggested by the authors, these yeasts are likely to be involved in the production of secondary defensive metabolites and architectural structures, but, are these services enough to explain the diversity found in macrolichens? This paper is an appealing example of a multipartite symbiosis where the different partners share an ancient evolutionary history. References [1] Spribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al. 2016. Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens. Science 353:488–92. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8287 [2] Tsuchida T, Koga R, Horikawa M, et al. 2010. Symbiotic Bacterium Modifies Aphid Body Color. Science 330:1102–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1195463 [3] Clay K. 1988. Fungal Endophytes of Grasses: A Defensive Mutualism between Plants and Fungi. Ecology 69:10–16. doi: 10.2307/1943155 [4] Moran NA. 2007. Symbiosis as an adaptive process and source of phenotypic complexity. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 104:8627–8633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611659104 | Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens | Spribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al. | For over 140 years, lichens have been regarded as a symbiosis between a single fungus, usually an ascomycete, and a photosynthesizing partner. Other fungi have long been known to occur as occasional parasites or endophytes, but the one lichen–one ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Life History, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Speciation, Species interactions | Enric Frago | 2016-12-15 05:46:14 | View | |

18 Jan 2021

Trait plasticity and covariance along a continuous soil moisture gradientJ Grey Monroe, Haoran Cai, David L Des Marais https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.17.952853Another step towards grasping the complexity of the environmental response of traitsRecommended by Benoit Pujol based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersOne can only hope that one day, we will be able to evaluate how the ecological complexity surrounding natural populations affects their ability to adapt. This is more like a long term quest than a simple scientific aim. Many steps are heading in the right direction. This paper by Monroe and colleagues (2021) is one of them. References Gienapp P. & J.E. Brommer. 2014. Evolutionary dynamics in response to climate change. In: Charmentier A, Garant D, Kruuk LEB, editors. Quantitative genetics in the wild. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Oxford. pp. 254–273. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199674237.003.0015 | Trait plasticity and covariance along a continuous soil moisture gradient | J Grey Monroe, Haoran Cai, David L Des Marais | <p>Water availability is perhaps the greatest environmental determinant of plant yield and fitness. However, our understanding of plant-water relations is limited because it is primarily informed by experiments considering soil moisture variabilit... |  | Phenotypic Plasticity | Benoit Pujol | 2020-02-20 16:34:40 | View | |

01 Mar 2024

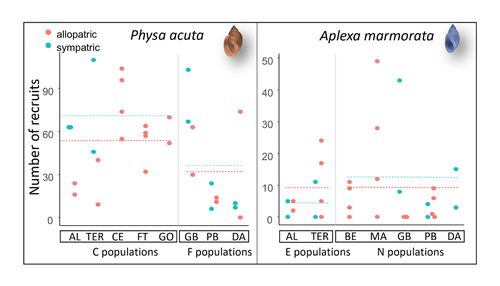

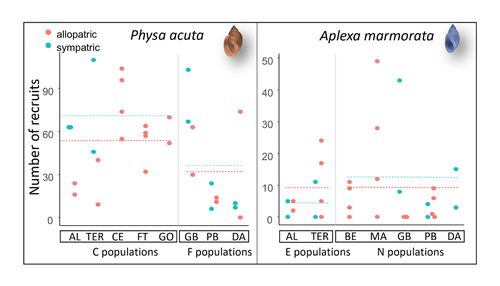

Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident speciesElodie Chapuis, Philippe Jarne, Patrice David https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.25.563987The evolution of a hobo snailRecommended by Ben Phillips based on reviews by David Reznick and 2 anonymous reviewersAt the very end of a paper entitled "Copepodology for the ornithologist" Hutchinson (1951) pointed out the possibility of 'fugitive species'. A fugitive species, said Hutchinson, is one that we would typically think of as competitively inferior. Wherever it happens to live it will eventually be overwhelmed by competition from another species. We would expect it to rapidly go extinct but for one reason: it happens to be a much better coloniser than the other species. Now all we need to explain its persistence is a dose of space and a little disturbance: a world in which there are occasional disturbances that cause local extinction of the dominant species. Now, argued Hutchinson, we have a recipe for persistence, albeit of a harried kind. As Hutchinson put it, fugitive species "are forever on the move, always becoming extinct in one locality as they succumb to competition, and always surviving as they reestablish themselves in some other locality." It is a fascinating idea, not just because it points to an interesting strategy, but also because it enriches our idea of competition: competition for space can be just as important as competition for time. Hutchinson's idea was independently discovered with the advent of metapopulation theory (Levins 1971; Slatkin 1974) and since then, of course, ecologists have gone looking, and they have unearthed many examples of species that could be said to have a fugitive lifestyle. These fugitive species are out there, but we don't often get to see them evolve. In their recent paper, Chapuis et al. (2024) make a convincing case that they have seen the evolution of a fugitive species. They catalog the arrival of an invasive freshwater snail on Guadeloupe in the Lesser Antilles, and they wonder what impact this snail's arrival might have on a native freshwater snail. This is a snail invasion, so it has been proceeding at a majestic pace, allowing the researchers to compare populations of the native snail that are completely naive to the invader with those that have been exposed to the invader for either a relatively short period (<20 generations) or longer periods (>20 generations). They undertook an extensive set of competition assays on these snails to find out which species were competitively superior and how the native species' competitive ability has evolved over time. Against naive populations of the native, the invasive snail turns out to be unequivocally the stronger competitor. (This makes sense; it probably wouldn't have been able to invade if it wasn't.) So what about populations of the native snail that have been exposed for longer, that have had time to adapt? Surprisingly these populations appear to have evolved to become even weaker competitors than they already were. So why is it that the native species has not simply been driven extinct? Drawing on their previous work on this system, the authors can explain this situation. The native species appears to be the better coloniser of new habitats. Thus, it appears that the arrival of the invasive species has pushed the native species into a different place along the competition-colonisation axis. It has sacrificed competitive ability in favour of becoming a better coloniser; it has become a fugitive species in its own backyard. This is a really nice empirical study. It is a large lab study, but one that makes careful sampling around a dynamic field situation. Thus, it is a lab study that informs an earlier body of fieldwork and so reveals a fascinating story about what is happening in the field. We are left not only with a particularly compelling example of character displacement towards a colonising phenotype but also with something a little less scientific: the image of a hobo snail, forever on the run, surviving in the spaces in between. References Chapuis E, Jarne P, David P (2024) Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident species. bioRxiv, 2023.10.25.563987, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.25.563987 Hutchinson, G.E. (1951) Copepodology for the Ornithologist. Ecology 32: 571–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/1931746 Levins, R., and D. Culver. (1971) Regional Coexistence of Species and Competition between Rare Species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 68, no. 6: 1246–48. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.68.6.1246. Slatkin, Montgomery. (1974) Competition and Regional Coexistence. Ecology 55, no. 1: 128–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1934625. | Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident species | Elodie Chapuis, Philippe Jarne, Patrice David | <p style="text-align: justify;">Biological invasions by phylogenetically and ecologically similar competitors pose an evolutionary challenge to native species. Cases of character displacement following invasions suggest that they can respond to th... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Species interactions | Ben Phillips | 2023-10-26 15:49:33 | View | |

31 Jan 2018

Identifying drivers of parallel evolution: A regression model approachSusan F Bailey, Qianyun Guo, Thomas Bataillon https://doi.org/10.1101/118695A new statistical tool to identify the determinant of parallel evolutionRecommended by Stephanie Bedhomme based on reviews by Bastien Boussau and 1 anonymous reviewerIn experimental evolution followed by whole genome resequencing, parallel evolution, defined as the increase in frequency of identical changes in independent populations adapting to the same environment, is often considered as the product of similar selection pressures and the parallel changes are interpreted as adaptive. References [1] Bailey SF, Guo Q and Bataillon T (2018) Identifying drivers of parallel evolution: A regression model approach. bioRxiv 118695, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/118695 [2] Lang GI, Rice DP, Hickman, MJ, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Botstein D, and Desai MM (2013) Pervasive genetic hitchhiking and clonal interference in forty evolving yeast populations. Nature 500: 571–574. doi: 10.1038/nature12344 | Identifying drivers of parallel evolution: A regression model approach | Susan F Bailey, Qianyun Guo, Thomas Bataillon | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (http://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100045). Parallel evolution, defined as identical changes arising in independent populations, is often attributed... |  | Experimental Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Stephanie Bedhomme | 2017-03-22 14:54:48 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer