CALATAYUD Joaquin

- , University of Alcalá, Alcalá de Henares, Spain

- Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Species interactions

Recommendations: 0

Reviews: 2

Reviews: 2

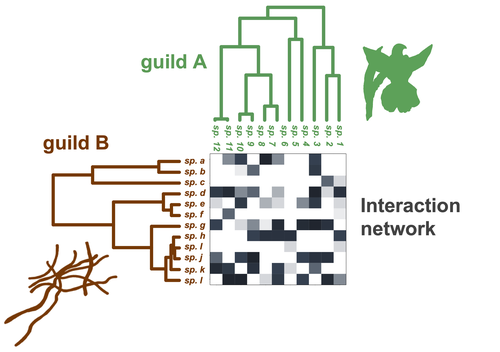

Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks

Testing for phylogenetic signal in species interaction networks

Recommended by Alejandro Gonzalez-Voyer based on reviews by Joaquin Calatayud and Thomas GuillermeSpecies are immersed within communities in which they interact mutualistically, as in pollination or seed dispersal, or nonreciprocally, such as in predation or parasitism, with other species and these interactions play a paramount role in shaping biodiversity (Bascompte and Jordano 2013). Researchers have become increasingly interested in the processes that shape these interactions and how these influence community structure and responses to disturbances. Species interactions are often described using bipartite interaction networks and one important question is how the evolutionary history of the species involved influences the network, including whether there is phylogenetic signal in interactions, in other words whether closely related species interact with other closely related species (Bascompte and Jordano 2013, Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022). To address this question different approaches, correlative and model-based, have been developed to test for phylogenetic signal in interactions, although comparative analyses of the performance of these different metrics are lacking. In their article Perez-Lamarque et al. (2022) set out to test the statistical performance of two widely-used methods, Mantel tests and Phylogenetic Bipartite Linear Models (PBLM; Ives and Godfray 2006) using simulations. Phylogenetic signal is measured as the degree to which distance to the nearest common ancestor predicts the observed similarity in trait values among species. In species interaction networks, the data are actually the between-species dissimilarity among interacting species (Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022), and typical approaches to test for phylogenetic signal cannot be used. However, the Mantel test provides a useful means of analyzing the correlation between two distance matrices, the between-species phylogenetic distance and the between-species dissimilarity in interactions. The PBLM approach, on the other hand, assumes that interactions between species are influenced by unobserved traits that evolve along the phylogenies following a given phenotypic evolution model and the parameters of this model are interpreted in terms of phylogenetic signal (Ives and Godfray 2006). Perez-Lamarque et al (2022) found that the model-based PBLM approach has a high type-I error rate, in other words it often detected phylogenetic signal when there was none. The simple Mantel test was found to present a low type-I error rate and moderate statistical power. However, it tended to overestimate the degree to which species interact with dissimilar partners. In addition to the aforementioned analyses, the authors also tested whether the simple Mantel test was able to detect phylogenetic signal in interactions among species within a given clade in the phylogeny, as phylogenetic signal in species interactions may be localized within specific clades. The article concludes with general guidelines for users wishing to test phylogenetic signal in their interaction networks and illustrates them with an example of an orchid-mycorrhizal fungus network from the oceanic island of La Réunion (Martos et al 2012). This broadly accessible article provides a valuable analysis of the performance of tests of phylogenetic signal in interaction networks enabling users to make informed choices of the analytical methods they wish to employ, and provide useful and detailed guidelines. Therefore, the work should be of broad interest to researchers studying species interactions.

References

Bascompte J, Jordano P (2013) Mutualistic Networks. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400848720

Ives AR, Godfray HCJ (2006) Phylogenetic Analysis of Trophic Associations. The American Naturalist, 168, E1–E14. https://doi.org/10.1086/505157

Martos F, Munoz F, Pailler T, Kottke I, Gonneau C, Selosse M-A (2012) The role of epiphytism in architecture and evolutionary constraint within mycorrhizal networks of tropical orchids. Molecular Ecology, 21, 5098–5109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05692.x

Perez-Lamarque B, Maliet O, Pichon B, Selosse M-A, Martos F, Morlon H (2022) Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks. bioRxiv, 2021.08.30.458192, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.30.458192

Ancient tropical extinctions contributed to the latitudinal diversity gradient

One (more) step towards a dynamic view of the Latitudinal Diversity Gradient

Recommended by Joaquín Hortal and Juan Arroyo based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Joaquín Hortal, Arne Mooers, Joaquin Calatayud and 2 anonymous reviewersThe Latitudinal Diversity Gradient (LDG) has fascinated natural historians, ecologists and evolutionary biologists ever since [1] described it about 200 years ago [2]. Despite such interest, agreement on the origin and nature of this gradient has been elusive. Several tens of hypotheses and models have been put forward as explanations for the LDG [2-3], that can be grouped in ecological, evolutionary and historical explanations [4] (see also [5]). These explanations can be reduced to no less than 26 hypotheses, which account for variations in ecological limits for the establishment of progressively larger assemblages, diversification rates, and time for species accumulation [5]. Besides that, although in general the tropics hold more species, different taxa show different shapes and rates of spatial variation [6], and a considerable number of groups show reverse patterns, with richer assemblages in cold temperate regions (see e.g. [7-9]).

Understanding such complexity needs integrating ecological and evolutionary research into the wide temporal and spatial perspectives provided by the burgeoning field of biogeography. This integrative discipline ¬–that traces back to Humboldt himself (e.g. [10])– seeks to put together historical and functional explanations to explain the complex dynamics of Earth’s biodiversity. Different to quantum physicists, biogeographers cannot pursue the ultimate principle behind the patterns we observe in nature due to the interplay of causes and effects, which in fact tell us that there is not such a single principle. Rather, they need to identify an array of basic principles coming from different perspectives, to then integrate them into models that provide realistic –but never simple– explanations to biodiversity gradients such as LDG (see, e.g., [5; 11]). That is, rather than searching for a sole explanation, research on the LDG must aim to identify as many signals hidden in the pattern as possible, and provide hypotheses or models that account for these signals. To later integrate them and, whenever possible, to validate them with empirical data on the organisms’ distribution, ecology and traits, phylogenies, fossils, etc.

Within this context, Meseguer & Condamine [12] provide a novel perspective to LDG research using phylogenetic and fossil evidence on the origin and extinction of taxa within the turtle, crocodile and lizard (i.e. squamate) lineages. By digging into deep time down to the Triassic (about 250 Myr ago) they are able to identify several episodes of flattening and steepening of the LDG for these three clades. Strikingly, their results show similar diversification rates in the northern hemisphere and in the equator during the over 100 Myr long global greenhouse period that extends from the late Jurassic to the Cretaceous and early Neogene. During this period, the LDG for these three groups would have appeared quite even across a mainly tropical Globe, although the equatorial regions were apparently much more evolutionarily dynamic. The equator shows much higher rates of origination and extinction of branches throughout the Cretaceous, but they counteract each other so net diversification is similar to that of the northern hemisphere in all three groups. The transition to a progressively colder Earth in the Paleogene (starting around 50 Myr ago) provokes a mass extinction in the three clades, which is compensated in the equator by the dispersal of many taxa from the areas that currently pertain to the Holarctic biogeographical realm. Finally, during the coldhouse Earth’s climatic conditions of the Neogene only squamates show significant positive diversification rates in extratropical areas, while the diversity of testudines remains, and crocodiles continue declining progressively towards oblivion in the whole world.

Meseguer & Condamine [12] attribute these temporal patterns to the so-called asymmetric gradient of extinction and dispersal (AGED) framework. Here, the dynamics of extinction-at and dispersal-from high latitudes during colder periods increase the steepness of the LDG. Whereas the gradient flattens when Earth warms up as a result of dispersal from the equator followed by increased diversification in extratropical regions. This idea in itself is not new, for the influence of climatic oscillations on diversification rates is well known, at least for the Pleistocene Ice Ages [13], as is the effect of niche conservatism on the LDG [14]. Nevertheless, Meseguer & Condamine’s AGED provides a synthetic verbal model that could allow integrating the three main types of processes behind the LDG into a single framework. To do this it would be necessary to combine AGED’s cycles of dispersal and diversification with realistic models of: (1) the ecological limits to host rich assemblages in the colder and less productive temperate climatic domains; (2) the variations in diversification rates with shifts in temperature and/or energy regimes; and (3) the geographical patterns of climatic oscillation through time that determine the time for species accumulation in each region.

Integrating these models may allow transposing Meseguer & Condamine’s [12] framework into the more mechanistic macroecological models advocated by Pontarp et al. [5]. This type of mechanistic models has been already used to understand the development of biodiversity gradients through the climatic oscillations of the Pleistocene and the Quaternary (e.g. [11]). So the challenge in this case would be to generate a realistic scenario of geographical dynamics that accounts for plate tectonics and long-term climatic oscillations. This is still a major gap and we would benefit from the integrated work by historical geologists and climatologists here. For instance, there is little doubt about the progressive cooling through the Cenozoic based in isotope recording in sea floor sediments [15]. Meseguer & Condamine [12] use this evidence for separating greenhouse, transition and coldhouse world scenarios, which should not be a problem for these rough classes. However, a detailed study of the evolutionary correlation of true climate variables across the tree of life is still pending, as temperature is inferred only for sea water in an ice-free ocean, say earlier half of the Cenozoic [15]. Precipitation regime is even less known. Such scenario would provide a scaffold upon which the temporal dynamics of several aspects of the generation and loss of biodiversity can be modelled. Additionally, one of the great advantages of selecting key clades to study the LDG would be to determine the functional basis of diversification. There are species traits that are well known to affect speciation and extinction probabilities, such as reproductive strategies or life histories (e.g. [16]). Whereas these traits might also be a somewhat redundant effect of climatic causes, they might foster (i.e. “extended reinforcement”, [17]) or slow diversification. Even so, it is unlikely that such a model would account for all the latitudinal variation in species richness. But it will at least provide a baseline for the main latitudinal variations in the diversity of the regional communities (sensu [18]) worldwide. Within this context the effects of recent ecological, evolutionary and historical processes, such as environmental heterogeneity, current diversification rates or glacial cycles, will only modify the general LDG pattern resulting from the main processes contained in Meseguer & Condamine’s AGED, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of the geographical gradients of diversity.

References

[1] Humboldt, A. v. (1808). Ansichten der Natur, mit wissenschaftlichen Erläuterungen. J. G. Cotta, Tübingen.

[2] Hawkins, B. A. (2001). Ecology's oldest pattern? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 16, 470. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02197-8

[3] Lomolino, M. V., Riddle, B. R. & Whittaker, R. J. (2017). Biogeography. Fifth Edition. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Massachussets.

[4] Mittelbach, G. G., Schemske, D. W., Cornell, H. V., Allen, A. P., Brown, J. M., Bush, M. B., Harrison, S. P., Hurlbert, A. H., Knowlton, N., Lessios, H. A., McCain, C. M., McCune, A. R., McDade, L. A., McPeek, M. A., Near, T. J., Price, T. D., Ricklefs, R. E., Roy, K., Sax, D. F., Schluter, D., Sobel, J. M. & Turelli, M. (2007). Evolution and the latitudinal diversity gradient: speciation, extinction and biogeography. Ecology Letters, 10, 315-331. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01020.x

[5] Pontarp, M., Bunnefeld L., Cabral, J. S., Etienne, R. S., Fritz, S. A., Gillespie, R. Graham, C. H., Hagen, O., Hartig, F., Huang, S., Jansson, R., Maliet, O., Münkemüller, T., Pellissier, L., Rangel, T. F., Storch, D., Wiegand, T. & Hurlbert, A. H. (2019). The latitudinal diversity gradient: novel understanding through mechanistic eco-evolutionary models. Trends in ecology & evolution, 34, 211-223. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2018.11.009

[6] Hillebrand, H. (2004). On the generality of the latitudinal diversity gradient. The American Naturalist, 163, 192-211. doi: 10.1086/381004

[7] Santos, A. M. C. & Quicke, D. L. J. (2011). Large-scale diversity patterns of parasitoid insects. Entomological Science, 14, 371-382. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8298.2011.00481.x

[8] Morinière, J., Van Dam, M. H., Hawlitschek, O., Bergsten, J., Michat, M. C., Hendrich, L., Ribera, I., Toussaint, E. F. A. & Balke, M. (2016). Phylogenetic niche conservatism explains an inverse latitudinal diversity gradient in freshwater arthropods. Scientific Reports, 6, 26340. doi: 10.1038/srep26340

[9] Weiser, M. D., Swenson, N. G., Enquist, B. J., Michaletz, S. T., Waide, R. B., Zhou, J. & Kaspari, M. (2018). Taxonomic decomposition of the latitudinal gradient in species diversity of North American floras. Journal of Biogeography, 45, 418-428. doi: 10.1111/jbi.13131

[10] Humboldt, A. v. (1805). Essai sur la geographie des plantes; accompagné d'un tableau physique des régions equinoxiales. Levrault, Paris.

[11] Rangel, T. F., Edwards, N. R., Holden, P. B., Diniz-Filho, J. A. F., Gosling, W. D., Coelho, M. T. P., Cassemiro, F. A. S., Rahbek, C. & Colwell, R. K. (2018). Modeling the ecology and evolution of biodiversity: Biogeographical cradles, museums, and graves. Science, 361, eaar5452. doi: 10.1126/science.aar5452

[12] Meseguer, A. S. & Condamine, F. L. (2019). Ancient tropical extinctions contributed to the latitudinal diversity gradient. bioRxiv, 236646, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/236646

[13] Jansson, R., & Dynesius, M. (2002). The fate of clades in a world of recurrent climatic change: Milankovitch oscillations and evolution. Annual review of ecology and systematics, 33(1), 741-777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.150520

[14] Wiens, J. J., & Donoghue, M. J. (2004). Historical biogeography, ecology and species richness. Trends in ecology & evolution, 19, 639-644. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.09.011

[15] Zachos, J. C., Dickens, G. R., & Zeebe, R. E. (2008). An early Cenozoic perspective on greenhouse warming and carbon-cycle dynamics. Nature, 451, 279-283. doi: 10.1038/nature06588

[16] Zúñiga-Vega, J. J., Fuentes-G, J. A., Ossip-Drahos, A. G., & Martins, E. P. (2016). Repeated evolution of viviparity in phrynosomatid lizards constrained interspecific diversification in some life-history traits. Biology letters, 12, 20160653. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0653

[17] Butlin, R. K., & Smadja, C. M. (2018). Coupling, reinforcement, and speciation. The American Naturalist, 191, 155-172. doi: 10.1086/695136

[18] Ricklefs, R. E. (2015). Intrinsic dynamics of the regional community. Ecology letters, 18, 497-503. doi: 10.1111/ele.12431