Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

29 Sep 2017

Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of the South American continentMichael D. Pirie, Paul J. M. Maas, Rutger A. Wilschut, Heleen Melchers-Sharrott & Lars W. Chatrou 10.1101/141127Unravelling the history of Neotropical plant diversificationRecommended by Hervé Sauquet based on reviews by Thomas Couvreur and Hervé SauquetSouth American rainforests, particularly the Tropical Andes, have been recognized as the hottest spot of plant biodiversity on Earth, while facing unprecedented threats from human impact [1,2]. Considerable research efforts have recently focused on unravelling the complex geological, bioclimatic, and biogeographic history of the region [3,4]. While many studies have addressed the question of Neotropical plant diversification using parametric methods to reconstruct ancestral areas and patterns of dispersal, Pirie et al. [5] take a distinct, complementary approach. Based on a new, near-complete molecular phylogeny of two Neotropical genera of the flowering plant family Annonaceae, the authors modelled the ecological niche of each species and reconstructed the history of niche differentiation across the region. The main conclusion is that, despite similar current distributions and close phylogenetic distance, the two genera experienced rather distinct processes of diversification, responding differently to the major geological events marking the history of the region in the last 20 million years (Andean uplift, drainage of Lake Pebas, and closure of the Panama Isthmus). As a researcher who has not personally worked on Neotropical biogeography, I found this paper captivating and especially enjoyed very much reading the Introduction, which sets out the questions very clearly. The strength of this paper is the near-complete diversity of species the authors were able to sample in each clade and the high-quality data compiled for the niche models. I would recommend this paper as a nice example of a phylogenetic study aimed at unravelling the detailed history of Neotropical plant diversification. While large, synthetic meta-analyses of many clades should continue to seek general patterns [4,6], careful studies restricted on smaller, but well controlled and sampled datasets such as this one are essential to really understand tropical plant diversification in all its complexity. References [1] Antonelli A, and Sanmartín I. 2011. Why are there so many plant species in the Neotropics? Taxon 60, 403–414. [2] Mittermeier RA, Robles-Gil P, Hoffmann M, Pilgrim JD, Brooks TB, Mittermeier CG, Lamoreux JL and Fonseca GAB. 2004. Hotspots revisited: Earths biologically richest and most endangered ecoregions. CEMEX, Mexico City, Mexico 390pp [3] Antonelli A, Nylander JAA, Persson C and Sanmartín I. 2009. Tracing the impact of the Andean uplift on Neotropical plant evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA 106, 9749–9754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811421106 [4] Hoorn C, Wesselingh FP, ter Steege H, Bermudez MA, Mora A, Sevink J, Sanmartín I, Sanchez-Meseguer A, Anderson CL, Figueiredo JP, Jaramillo C, Riff D, Negri FR, Hooghiemstra H, Lundberg J, Stadler T, Särkinen T and Antonelli A. 2010. Amazonia through time: Andean uplift, climate change, landscape evolution, and biodiversity. Science 330, 927–931. doi: 10.1126/science.1194585 [5] Pirie MD, Maas PJM, Wilschut R, Melchers-Sharrott H and Chatrou L. 2017. Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of the South American continent. bioRxiv, 141127, ver. 3 of 28th Sept 2017. doi: 10.1101/141127 [6] Bacon CD, Silvestro D, Jaramillo C, Tilston Smith B, Chakrabartye P and Antonelli A. 2015. Biological evidence supports an early and complex emergence of the Isthmus of Panama. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA 112, 6110–6115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423853112 | Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of the South American continent | Michael D. Pirie, Paul J. M. Maas, Rutger A. Wilschut, Heleen Melchers-Sharrott & Lars W. Chatrou | Much of the immense present day biological diversity of Neotropical rainforests originated from the Miocene onwards, a period of geological and ecological upheaval in South America. We assess the impact of the Andean orogeny, drainage of lake Peba... |  | Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Hervé Sauquet | Hervé Sauquet, Thomas Couvreur | 2017-06-03 21:25:48 | View |

24 Oct 2019

Testing host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects : a phylogenetic perspectiveEmmanuelle Jousselin, Marianne Elias https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.09510v1Phylogenetic approaches for reconstructing macroevolutionary scenarios of phytophagous insect diversificationRecommended by Hervé Sauquet based on reviews by Brian O'Meara and 1 anonymous reviewerPlant-animal interactions have long been identified as a major driving force in evolution. However, only in the last two decades have rigorous macroevolutionary studies of the topic been made possible, thanks to the increasing availability of densely sampled molecular phylogenies and the substantial development of comparative methods. In this extensive and thoughtful perspective [1], Jousselin and Elias thoroughly review current hypotheses, data, and available macroevolutionary methods to understand how plant-insect interactions may have shaped the diversification of phytophagous insects. First, the authors review three main hypotheses that have been proposed to lead to host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects: the ‘escape and radiate’, ‘oscillation’, and ‘musical chairs’ scenarios, each with their own set of predictions. Jousselin and Elias then synthesize a vast core of recent studies on different clades of insects, where explicit phylogenetic approaches have been used. In doing so, they highlight heterogeneity in both the methods being used and predictions being tested across these studies and warn against the risk of subjective interpretation of the results. Lastly, they advocate for standardization of phylogenetic approaches and propose a series of simple tests for the predictions of host-driven speciation scenarios, including the characterization of host-plant range history and host breadth history, and diversification rate analyses. This helpful review will likely become a new point of reference in the field and undoubtedly help many researchers formalize and frame questions of plant-insect diversification in future studies of phytophagous insects. References [1] Jousselin, E., Elias, M. (2019). Testing Host-Plant Driven Speciation in Phytophagous Insects: A Phylogenetic Perspective. arXiv, 1910.09510, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.09510v1 | Testing host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects : a phylogenetic perspective | Emmanuelle Jousselin, Marianne Elias | During the last two decades, ecological speciation has been a major research theme in evolutionary biology. Ecological speciation occurs when reproductive isolation between populations evolves as a result of niche differentiation. Phytophagous ins... |  | Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Speciation, Species interactions | Hervé Sauquet | 2019-02-25 17:31:33 | View | |

08 Feb 2019

Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenesAnouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo https://doi.org/10.1101/337477E5, the third oncogene of PapillomavirusRecommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Leonardo de Oliveira Martins and 1 anonymous reviewerPapillomaviruses (PVs) infect almost all mammals and possibly amniotes and bony fishes. While most of them have no significant effects on the hosts, some induce physical lesions. Phylogeny of PVs consists of a few crown groups [1], among which AlphaPVs that infect primates including human have been well studied. They are associated to largely different clinical manifestations: non-oncogenic PVs causing anogenital warts, oncogenic and non-oncogenic PVs causing mucosal lesions, and non-oncogenic PVs causing cutaneous warts. References [1] Bravo, I. G., & Alonso, Á. (2004). Mucosal human papillomaviruses encode four different E5 proteins whose chemistry and phylogeny correlate with malignant or benign growth. Journal of virology, 78, 13613-13626. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13613-13626.2004 | Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenes | Anouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo | <p>The clinical presentations of papillomavirus (PV) infections come in many different flavors. While most PVs are part of a healthy skin microbiota and are not associated to physical lesions, other PVs cause benign lesions, and only a handful of ... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Hirohisa Kishino | 2018-06-04 16:15:39 | View | |

26 Aug 2021

Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durabilityMéline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112Durability of plant resistance to diploid pathogenRecommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Loup Rimbaud and 1 anonymous reviewerDurability of plant resistance to diploid pathogen Hirohisa Kishino Based on the population genetic and epidemiologic model, Saubin et al. (2021) report that the resistant hosts generated by the breeding based on the gene-for-gene interaction is durable much longer against diploid pathogens than haploid pathogens. The avr allele of pathogen that confers the resistance is genetically recessive. The heterozygotes are not recognized by the resistant hosts and only the avr/avr homozygote is adaptive. As a result, the trajectory of avr allele frequency becomes more stochastic due to genetic drift. Although the paper focuses on the evolution of standing polymorphism, it seems obvious that the adaptive mutations in pathogen have much larger probability of being deleted from the population because the individuals own the avr allele mostly in the form of heterozygote at the initial phase after the mutation. Since only few among many models of plant resistance deployment study the case of diploid pathogen and the contribution of the pathogen life cycle, this work will add an important intellect to the literature (Rimbaud et al. 2021). From the study of host-parasite interaction in flax rust Melampsora lini, Flor (1942, 1955) showed that the host resistance is formed by the interaction of a host resistance gene and a corresponding pathogen gene. This gene-for-gene hypothesis has been supported by experimental evidence and has served as a basis of the methods of molecular breeding targeting the dominant R genes. However, modern agriculture provides the pathogen populations with the homogeneous environments and laid strong selection pressure on them. As a result, the newly developed resistant plants face the risk of immediate resistance breakdown (Möller and Stukenbrock 2017). Currently, quantitative resistance is getting attention as characters as a potential target for long-life (mild) resistant breeds (Lannou, 2012). They are polygenic and controlled partly by the same genes that mediate qualitative resistance but mostly by the genes that encode defense-related outputs such as strengthening of the cell wall or defense compound biosynthesis (Corwin and Kliebenstein, 2017). Progress of molecular genetics may overcome the technical difficulty (Bakkeren and Szabo, 2020). Saubin et al. (2021) notes that the pattern of genetic inheritance of the pathogen counterparts that respond to the host traits is crucial regarding with the durability of the resistant hosts. The resistance traits for which avr alleles are predicted to be recessive may be the targets of breeding. References Bakkeren, G., and Szabo, L. J. (2020) Progress on molecular genetics and manipulation of rust fungi. Phytopathology, 110, 532-543. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-07-19-0228-IA Corwin, J. A., and Kliebenstein, D. J. (2017) Quantitative resistance: more than just perception of a pathogen. The Plant Cell, 29, 655-665. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.16.00915 Flor, H. H. (1942) Inheritance of pathogenicity in a cross between physiological races 22 and 24 of Melampsova lini. Phytopathology, 35. Abstract. Flor, H. H. (1955) Host-parasite interactions in flax rust-its genetics and other implications. Phytopathology, 45, 680-685. Lannou, C. (2012) Variation and selection of quantitative traits in plant pathogens. Annual review of phytopathology, 50, 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-173031 Möller, M. and Stukenbrock, E. H. (2017) Evolution and genome architecture in fungal plant pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 15, 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.76 Rimbaud, L., Fabre, F., Papaïx, J., Moury, B., Lannou, C., Barrett, L. G., and Thrall, P. H. (2021) Models of Plant Resistance Deployment. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 59. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-020620-122134 Saubin, M., De Mita, S., Zhu, X., Sudret, B. and Halkett, F. (2021) Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability. bioRxiv, 2021.05.28.446112, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112 | Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability | Méline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett | <p>The breeding of resistant hosts based on the gene-for-gene interaction is crucial to address epidemics of plant pathogens in agroecosystems. Resistant host deployment strategies are developed and studied worldwide to decrease the probability of... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Hirohisa Kishino | 2021-06-03 07:58:16 | View | |

07 Jul 2017

Unmasking the delusive appearance of negative frequency-dependent selectionRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by David Baltrus and 2 anonymous reviewersExplaining the processes that maintain polymorphisms in a population has been a fundamental line of research in evolutionary biology. One of the main mechanisms identified that preserves genetic diversity is negative frequency-dependent selection (NFDS), which constitutes a powerful framework for interpreting the presence of persistent polymorphisms. Nevertheless, a number of patterns that are often explained by invoking NFDS may also be compatible with, and possibly more easily explained by, different processes. References [1] Brisson D. 2017. Negative frequency-dependent selection is frequently confounding. bioRxiv 113324, ver. 3 of 20th June 2017. doi: 10.1101/113324 [2] Heino M, Metz JAJ and Kaitala V. 1998. The enigma of frequency-dependent selection. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 13: 367-370. doi: 1016/S0169-5347(98)01380-9 | Negative frequency-dependent selection is frequently confounding | Dustin Brisson | The existence of persistent genetic variation within natural populations presents an evolutionary problem as natural selection and genetic drift tend to erode genetic diversity. Models of balancing selection were developed to account for the high ... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Ignacio Bravo | 2017-03-03 18:46:42 | View | |

13 Dec 2018

A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid waspsD. Di Giovanni, D. Lepetit, M. Boulesteix, M. Ravallec, J. Varaldi https://doi.org/10.1101/342758Genetic intimacy of filamentous viruses and endoparasitoid waspsRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Alejandro Manzano Marín and 1 anonymous reviewerViruses establish intimate relationships with the cells they infect. The virocell is a novel entity, different from the original host cell and beyond the mere combination of viral and cellular genetic material. In these close encounters, viral and cellular genomes often hybridise, combine, recombine, merge and excise. Such chemical promiscuity leaves genomics scars that can be passed on to descent, in the form of deletions or duplications and, importantly, insertions and back and forth exchange of genetic material between viruses and their hosts. References [1] Di Giovanni, D., Lepetit, D., Boulesteix, M., Ravallec, M., & Varaldi, J. (2018). A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid wasps. bioRxiv, 342758, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/342758 | A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid wasps | D. Di Giovanni, D. Lepetit, M. Boulesteix, M. Ravallec, J. Varaldi | <p>To circumvent host immune response, numerous hymenopteran endo-parasitoid species produce virus-like structures in their reproductive apparatus that are injected into the host together with the eggs. These viral-like structures are absolutely n... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution | Ignacio Bravo | 2018-07-18 15:59:14 | View | |

26 Oct 2021

Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North AfricaOlvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tournant L., Gazel F., Mody K., Khachtib Y., Roman A., Ursu T.M., Zakharov I.A., Belcram H., Harry M., Roth M., Simon J.C., Oram S., Ricard J.M., Agnello A., Beers E. H., Engelman J., Balti I., Salhi-Hannachi A., Zhang H., Tu H., Mottet C., Barrès B., Degra... https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.11.421644The evolutionary puzzle of the host-parasite-endosymbiont Russian doll for apples and aphidsRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewerEach individual multicellular organism, each of our bodies, is a small universe. Every living surface -skin, cuticle, bark, mucosa- is the home place to milliards of bacteria, fungi and viruses. They constitute our microbiota. Some of them are essential for certain organisms. Other could not live without their hosts. For many species, the relationship between host and microbiota is so close that their histories are inseparable. The recognition of this biological inextricability has led to the notion of holobiont as the organism ensemble of host and microbiota. When individuals of a particular animal or plant species expand their geographical range, it is the holobiont that expands. And these processes of migration, expansion and colonization are often accompanied by evolutionary and ecological innovations in the interspecies relationships, at the macroscopic level (e.g. novel predator-prey or host-parasite interactions) and at the microscopic level (e.g. changes in the microbiota composition). From the human point of view, these novel interactions can be economically disastrous if they involve and threaten important crop or cattle species. And this is especially worrying in the present context of genetic standardization and intensification for mass-production on the one hand, and of climate change on the other. With this perspective, the international team led by Amandine Cornille presents a study aiming at understanding the evolutionary history of the rosy apple aphid Dysaphis plantaginea Passerini, a major pest of the cultivated apple tree Malus domestica Borkh (1). The apple tree was probably domesticated in Central Asia, and later disseminated by humans over the world in different waves, and it was probably introduced in Europe by the Greeks. It is however unclear when and where D. plantaginea started parasitizing the cultivated apple tree. The ancestral D. plantaginea could have already infected the wild ancestor of current cultivated apple trees, but the aphid is not common in Central Asia. Alternatively, it may have gained access only later to the plant, possibly via a host jump, from Pyrus to Malus that may have occurred in Asia Minor or in the Caucasus. In the present preprint, Olvera-Vázquez and coworkers have analysed over 650 D. plantaginea colonies from 52 orchards in 13 countries, in Western, Central and Eastern Europe as well as in Morocco and the USA. The authors have analysed the genetic diversity in the sampled aphids, and have characterized as well the composition of the associated endosymbiont bacteria. The analyses detect substantial recent admixture, but allow to identify aphid subpopulations slightly but significantly differentiated and isolated by distance, especially those in Morocco and the USA, as well as to determine the presence of significant gene flow. This process of colonization associated to gene flow is most likely indirectly driven by human interactions. Very interestingly, the data show that this genetic diversity in the aphids is not reflected by a corresponding diversity in the associated microbiota, largely dominated by a few Buchnera aphidicola variants. In order to determine polarity in the evolutionary history of the aphid-tree association, the authors have applied approximate Bayesian computing and machine learning approaches. Albeit promising, the results are not sufficiently robust to assess directionality nor to confidently assess the origin of the crop pest. Despite the large effort here communicated, the authors point to the lack of sufficient data (in terms of aphid isolates), especially originating from Central Asia. Such increased sampling will need to be implemented in the future in order to elucidate not only the origin and the demographic history of the interaction between the cultivated apple tree and the rosy apple aphid. This knowledge is needed to understand how this crop pest struggles with the different seasonal and geographical selection pressures while maintaining high genetic diversity, conspicuous gene flow, differentiated populations and low endosymbiontic diversity. References

| Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North Africa | Olvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tour... | <p style="text-align: justify;">With frequent host shifts involving the colonization of new hosts across large geographical ranges, crop pests are good models for examining the mechanisms of rapid colonization. The microbial partners of pest insec... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics, Species interactions | Ignacio Bravo | 2020-12-11 19:22:54 | View | |

25 Sep 2023

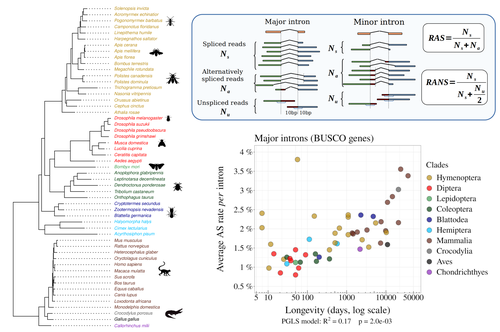

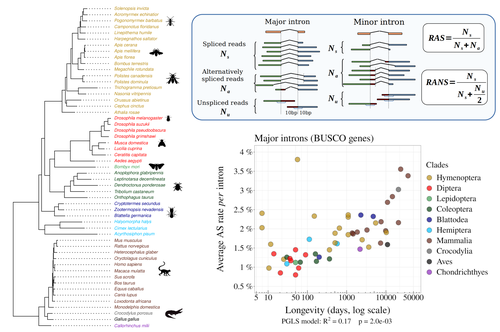

Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoansFlorian Benitiere, Anamaria Necsulea, Laurent Duret https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519597The drift barrier hypothesis and the limits to alternative splicing accuracyRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Lars M. Jakt and 2 anonymous reviewersAccurate information flow is central to living systems. The continuity of genomes through generations as well as the reproducible functioning and survival of the individual organisms require a faithful information transfer during replication, transcription and translation. The differential efficiency of natural selection against “mistakes” results in decreasing fidelity rates for replication, transcription and translation. At each level in the information flow chain (replication, transcription, translation), numerous complex molecular systems have evolved and been selected for preventing, identifying and, when possible, correcting or removing such “mistakes” arising during information transfer. However, fidelity cannot be improved ad infinitum. First, because of the limits imposed by the physical nature of the processes of copying and recoding information over different molecular supports: all mechanisms ensuring fidelity during biological information transfer ultimately rely on chemical kinetics and thermodynamics. The more accurate a copying process is, the lower the synthesis rate and the higher the energetic cost of correcting errors. Second, because of the limits imposed by random genetic drift: natural selection cannot effectively act on an allele that contributes with a small differential advantage unless effective population size is large. If s <1/Ne (or s <1/(2Ne) in diploids) the allele frequency in the population is de facto subject to neutral drift processes. In their preprint “Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans”, Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret explore the validity of this last mentioned “drift barrier” hypothesis for the case study of alternative splicing diversity in eukaryotes (Bénitière et al. 2022). Splicing refers to an ensemble of eukaryotic molecular processes mediated by a large number of proteins and ribonucleoproteins and involving nucleotide sequence recognition, that uses as a molecular substrate a precursor messenger RNA (mRNA), directly transcribed from the DNA, and produces a mature mRNA by removing introns and joining exons (Chow et al. 1977). Alternative splicing refers to the case in which different molecular species of mature mRNAs can be produced, either by cis-splicing processes acting on the same precursor mRNA, e.g. by varying the presence/absence of different exons or by varying the exon-exon boundaries, or by trans-splicing processes, joining exons from different precursor mRNA molecules. The diversity of mRNA molecular species generated by alternative splicing enlarges the molecular phenotypic space that can be generated from the same genotype. In humans, alternative splicing occurs in around 95% of the ca. 20,000 genes, resulting in ca. 100,000 medium-to-high abundance transcripts (Pan et al. 2008). In multicellular organisms, the frequency of alternatively spliced mRNAs varies between tissues and across ontogeny, often in a switch-like pattern (Wang et al. 2008). In the molecular and cell biology community, it is commonly accepted that splice variants contribute with specific functions (Marasco and Kornblihtt 2023) although there exists a discussion around the functional nature of low-frequency splice variants (see for instance the debate between Tress et al. 2017 and Blencowe 2017). The origin, diversity, regulation and evolutionary advantage of alternative splicing constitutes thus a playground of the selectionist-neutralist debate, with one extreme considering that most splice variants are mere “mistakes” of the splicing process (Pickrell et al. 2010), and the other extreme considering that alternative splicing is at the core of complexity in multicellular organisms, as it increases the genome coding potential and allows for a large repertoire of cell types (Chen et al. 2014). In their manuscript, Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret set the cursor towards the neutralist end of the gradient and test the hypothesis of whether the high alternative splice rate in “complex” organisms corresponds to a high rate of splicing “mistakes”, arising from the limit imposed by the drift barrier effect on the power of natural selection to increase accuracy (Bush et al. 2017). In their preprint, the authors convincingly show that in metazoans a fraction of the variation of alternative splicing rate is explained by variation in proxies of population size, so that species with smaller Ne display higher alternative splice rates. They communicate further that abundant splice variants tend to preserve the reading frame more often than low-frequency splice variants, and that the nucleotide splice signals in abundant splice variants display stronger evidence of purifying selection than those in low-frequency splice variants. From all the evidence presented in the manuscript, the authors interpret that “variation in alternative splicing rate is entirely driven by variation in the efficacy of selection against splicing errors”. The authors honestly present some of the limitations of the data used for the analyses, regarding i) the quality of the proxies used for Ne (i.e. body length, longevity and dN/dS ratio); ii) the heterogeneous nature of the RNA sequencing datasets (full organisms, organs or tissues; different life stages, sexes or conditions); and iii) mostly short RNA reads that do not fully span individual introns. Further, data from bacteria do not verify the herein communicated trends, as it has been shown that bacterial species with low population sizes do not display higher transcription error rates (Traverse and Ochman 2016). Finally, it will be extremely interesting to introduce a larger evolutionary perspective on alternative splicing rates encompassing unicellular eukaryotes, in which an intriguing interplay between alternative splicing and gene duplication has been communicated (Hurtig et al. 2020). The manuscript from Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret makes a significant advance to our understanding of the diversity, the origin and the physiology of post-transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms by emphasising the fundamental role of non-adaptive evolutionary processes and the upper limits to splicing accuracy set by genetic drift. References Bénitière F, Necsulea A, Duret L. 2023. Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519597 Blencowe BJ. 2017. The Relationship between Alternative Splicing and Proteomic Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci 42:407–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2017.04.001 Bush SJ, Chen L, Tovar-Corona JM, Urrutia AO. 2017. Alternative splicing and the evolution of phenotypic novelty. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 372:20150474. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0474 Chen L, Bush SJ, Tovar-Corona JM, Castillo-Morales A, Urrutia AO. 2014. Correcting for differential transcript coverage reveals a strong relationship between alternative splicing and organism complexity. Mol Biol Evol 31:1402–1413. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu083 Chow LT, Gelinas RE, Broker TR, Roberts RJ. 1977. An amazing sequence arrangement at the 5’ ends of adenovirus 2 messenger RNA. Cell 12:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(77)90180-5 Hurtig JE, Kim M, Orlando-Coronel LJ, Ewan J, Foreman M, Notice L-A, Steiger MA, van Hoof A. 2020. Origin, conservation, and loss of alternative splicing events that diversify the proteome in Saccharomycotina budding yeasts. RNA 26:1464–1480. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.075655.120 Marasco LE, Kornblihtt AR. 2023. The physiology of alternative splicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 24:242–254. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-022-00545-z Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. 2008. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet 40:1413–1415. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.259 Pickrell JK, Pai AA, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. 2010. Noisy splicing drives mRNA isoform diversity in human cells. PLoS Genet 6:e1001236. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001236 Traverse CC, Ochman H. 2016. Conserved rates and patterns of transcription errors across bacterial growth states and lifestyles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:3311–3316. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1525329113 Tress ML, Abascal F, Valencia A. 2017. Alternative Splicing May Not Be the Key to Proteome Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci 42:98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2016.08.008 Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP, Burge CB. 2008. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 456:470–476. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07509 | Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans | Florian Benitiere, Anamaria Necsulea, Laurent Duret | <p style="text-align: justify;">Most eukaryotic genes undergo alternative splicing (AS), but the overall functional significance of this process remains a controversial issue. It has been noticed that the complexity of organisms (assayed by the nu... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Ignacio Bravo | Anonymous | 2022-12-12 14:00:01 | View |

11 Oct 2022

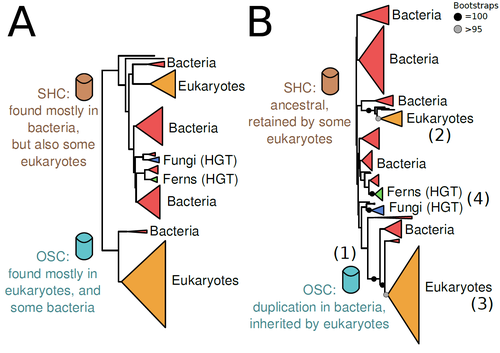

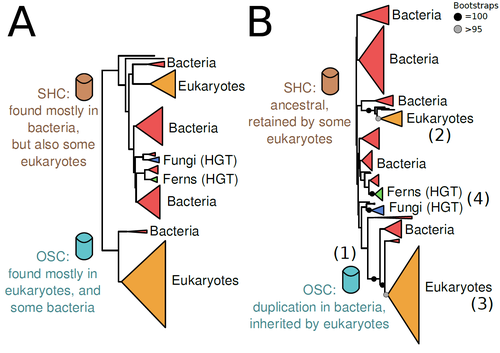

The Eukaryotic Last Common Ancestor Was Bifunctional for Hopanoid and Sterol ProductionWarren R Francis https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202004.0186.v5Gene family analysis suggests new evolutionary scenario for sterol and hopanoid biomarkersRecommended by Iker Irisarri based on reviews by Samuel Abalde, Denis Baurain and Jose Ramon Pardos-BlasSterols and hopanoids are sometimes used as biomarkers to infer the origin of certain groups of organisms. Traditionally, hopanoid-derived products in ancient rocks have been considered to indicate the presence of bacteria, whereas sterol derivatives have been considered to be exclusive to eukaryotes. However, a closer look at the topic reveals a rather complex distribution of either compound in both bacteria and eukaryotes. (1). The known biosynthetic pathways for sterols and hopanoids are similar but diverge at a critical step where two different enzymes are used: squalene-hopene cyclase (SHC) and oxidosqualene cyclase (OSC), the latter requiring oxygen. These two enzymes belong to the same gene family, whose complex evolutionary history is difficult to reconcile with the known species phylogeny. In this study (2), Dr. Warren R. Francis revisits the evolution of this gene family using an extended dataset with a broader taxonomic representation. In contrast to the traditional representation of the tree rooted between SHC and OSC paralogs (i.e., based on function), the author proposes that rooting the tree within bacterial SHCs and assuming a secondary origin of OSC is more parsimonious. This postulates SHC to be the ancestral function –retained in many extant bacteria and some eukaryotes– and OSC to have emerged later within bacteria –currently being mostly present in eukaryotes–. The reconstructed evolutionary history is arguably complex and can only be reconciled with the species' phylogeny by invoking many secondary losses. These losses are considered likely because many extant species acquire sterols and hopanoids by diet and lack one or both enzymes. Some cases of recent horizontal gene transfer are also proposed. In contrast to the dichotomy between bacterial SHCs and eukaryote OSCs, the new proposed scenario suggests that the eukaryote ancestor likely inherited both enzymes from bacteria and thus could be able to synthesize both sterols and hopanoids. Under this hypothesis, not only bacteria but also eukaryotes could be responsible for the hopane found in old rocks. This agrees with eukaryote fossils dating back to more than 1 billion years ago (3). Also, the observed increase of sterane levels in rocks ~600-700 million years old cannot be associated with the origin of eukaryotes, which is a much older event, but could rather reflect changes in atmospheric oxygen levels because oxygen is required for the synthesis of sterols by OSC. References 1. Santana-Molina C, Rivas-Marin E, Rojas AM, Devos DP (2020) Origin and Evolution of Polycyclic Triterpene Synthesis. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 37, 1925–1941. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa054 2. Francis WR (2022) The Eukaryotic Last Common Ancestor Was Bifunctional for Hopanoid and Sterol Production. Preprints, 2020040186, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202004.0186.v5 3. Butterfield NJ (2000) Bangiomorpha pubescens n. gen., n. sp.: implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity, and the Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes. Paleobiology, 26, 386–404. https://doi.org/10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0386:BPNGNS>2.0.CO;2 | The Eukaryotic Last Common Ancestor Was Bifunctional for Hopanoid and Sterol Production | Warren R Francis | <p>Steroid and hopanoid biomarkers can be found in ancient rocks and may give a glimpse of what life was present at that time. Sterols and hopanoids are produced by two related enzymes, though the evolutionary history of this protein family is com... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Molecular Evolution, Paleontology, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Iker Irisarri | 2021-01-13 16:03:29 | View | |

05 Aug 2020

Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognitaDjampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.30.069948DNA transposons drive genome evolution of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognitaRecommended by Ines Alvarez based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers

Duplications, mutations and recombination may be considered the main sources of genomic variation and evolution. In addition, sexual recombination is essential in purging deleterious mutations and allowing advantageous allelic combinations to occur (Glémin et al. 2019). However, in parthenogenetic asexual organisms, variation cannot be explained by sexual recombination, and other mechanisms must account for it. Although it is known that transposable elements (TE) may influence on genome structure and gene expression patterns, their role as a primary source of genomic variation and rapid adaptability has received less attention. An important role of TE on adaptive genome evolution has been documented for fungal phytopathogens (Faino et al. 2016), suggesting that TE activity might explain the evolutionary dynamics of this type of organisms. References [1] Bessereau J-L. 2006. Transposons in C. elegans. WormBook. 10.1895/wormbook.1.70.1 | Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita | Djampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin | <p>Despite reproducing without sexual recombination, the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita is adaptive and versatile. Indeed, this species displays a global distribution, is able to parasitize a large range of plants and can overcome plant ... | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Ines Alvarez | 2020-05-04 11:43:14 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer