Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

19 Feb 2018

Genomic imprinting mediates dosage compensation in a young plant XY systemAline Muyle, Niklaus Zemp, Cecile Fruchard, Radim Cegan, Jan Vrana, Clothilde Deschamps, Raquel Tavares, Franck Picard, Roman Hobza, Alex Widmer, Gabriel Marais https://doi.org/10.1101/179044Dosage compensation by upregulation of maternal X alleles in both males and females in young plant sex chromosomesRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Judith Mank based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersSex chromosomes evolve as recombination is suppressed between the X and Y chromosomes. The loss of recombination on the sex-limited chromosome (the Y in mammals) leads to degeneration of both gene expression and gene content for many genes [1]. Loss of gene expression or content from the Y chromosome leads to differences in gene dose between males and females for X-linked genes. Because expression levels are often correlated with gene dose [2], these hemizygous genes have a lower expression levels in the heterogametic sex. This in turn disrupts the stoichiometric balance among genes in protein complexes that have components on both the sex chromosomes and autosomes [3], which could have serious deleterious consequences for the heterogametic sex. References | Genomic imprinting mediates dosage compensation in a young plant XY system | Aline Muyle, Niklaus Zemp, Cecile Fruchard, Radim Cegan, Jan Vrana, Clothilde Deschamps, Raquel Tavares, Franck Picard, Roman Hobza, Alex Widmer, Gabriel Marais | <p>During the evolution of sex chromosomes, the Y degenerates and its expression gets reduced relative to the X and autosomes. Various dosage compensation mechanisms that recover ancestral expression levels in males have been described in animals.... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Expression Studies, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Tatiana Giraud | 2017-09-20 20:39:46 | View | |

21 Nov 2022

Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughsElisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard https://doi.org/10.1101/679472The variety of bread-making practices promotes diversity conservation in food microbial communitiesRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Jeanne Ropars based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersDomesticated organisms are excellent models for understanding ecology and evolution and they are important for our food production and safety. While less studied than plants and animals, micro-organisms have also been domesticated, in particular for food fermentation [1]. The most studied domesticated micro-organism is the yeast used to make wine, beer and bread, Saccharomyces cerevisiae [2, 3, 4]. Filamentous fungi used for cheese-making have recently gained interest, for example Penicillium roqueforti used to make blue cheeses and P. camemberti to make soft cheeses [5, 6, 7, 8]. As for plants and animals, domestication has led to beneficial traits for food production in fermenting fungi, but also to bottlenecks and degeneration [6, 7, 9]; P. camemberti for example does not produce enough spores any more for optimal culture and inoculation and P. roqueforti has lost sexual fertility [9]. The loss of genetic diversity and of species diversity in our food production system is concerning for multiple reasons : i) it jeopardizes future improvement in the face of global changes ; ii) it causes the loss of evolved diversity during centuries under human selection, and therefore of beneficial characteristics and specificities that we may never be able to recover ; iii) it leads to degeneration in the few cultivated strains; iv) it impoverishes the diversity of our food products and local adaptation of production practices. The study of domesticated fungi used for food fermentation has focused so far on the evolution of lineages and on their metabolic specificities. Microbiological assemblages and species diversity have been much less studied, while they likely also have a strong impact on the quality and safety of final products. This study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] addresses this question, using an interdisciplinary participatory research approach including bakers, psycho-sociologists and microbiologists to analyse bread-making practices and their impact on microbial communities in sourdough. Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] identified two distinct groups of bread-making practices based on interviews and surveys, with farmer-like practices (low bread production, use of ancient wheat populations, manual kneading, working at ambient temperature, long fermentation periods and no use of commercial baker’s yeast) versus more intensive, artisanal-like practices. Metabarcoding and microbial culture-based analyses showed that the well-known baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was, surprisingly, not the most common species in French organic sourdoughs. Kazachstania was the most represented yeast genus over all sourdoughs, both in terms of read abundance and of species diversity. Kazachstania species were also often dominant in individual sourdoughs, but Saccharomyces uvarum or Torulaspora delbrueckii could also be the dominant yeast species. Metabarcoding analyses further revealed that the composition of the fungal communities differed between the farmer-like and more intensive practices, representing the first evidence of the influence of artisanal practices on microbial communities. The fungal communities were impacted by a combination of bread-making variables including the type of wheat varieties, the length of fermentation, the quantity of bread made per week and the use of commercial yeast. Maintaining on farm less intensive bread-making practices, may allow the preservation of typical species and phenotypic diversity in microbial communities in sourdough. Farmer-like practices did not lead to higher diversity within sourdoughs but, overall, the diversity of bread-making practices allow maintaining a larger diversity in sourdoughs. For example, different Kazachstania species were most abundant in sourdoughs from artisanal-like and farmer-like practices. Interviews with the bakers suggested the role of dispersal of Kazachstania species in shaping sourdough microbial communities, dispersal occurring by seed exchanges, sourdough mixing or gifts, bread-making training in common or working in one another’s bakery. Nikolai Vavilov [11] had already highlighted for crops the importance of isolated cultures and selection in different farms for generating and preserving crop diversity, but also the importance of seed exchange for fostering adaptation. Furthermore, one of the yeast frequently found in artisanal sourdoughs, Kazachstania humilis, displayed phenotypic differences between sourdough and non-sourdough strains, suggesting domestication. The sourdough strains exhibited significantly higher CO2 production rate and a lower fermentation latency-phase time. The study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] is thus novel and inspiring in showing the importance of interdisciplinary studies, combining metabarcoding, microbiology and interviews for assessing the composition and diversity of microbial communities in human-made food, and in revealing the impact of artisanal-like bread-making practices in preserving microbial community diversity. Interdisciplinary studies are still rare but have already shown the importance of combining ethno-ecology, biology and evolution to decipher the role of human practices on genetic diversity in crops, animals and food microorganisms and to help preserving genetic resources [12]. For example, in the case of the bread wheat Triticum aestivum, such interdisciplinary studies have shown that genetic diversity has been shaped by farmers’ seed diffusion and farming practices [13]. We need more of such interdisciplinary studies on the impact of farmer versus industrial agricultural and food-making practices as we urgently need to preserve the diversity of micro-organisms used in food production that we are losing at a rapid pace [6, 7, 14]. References [1] Dupont J, Dequin S, Giraud T, Le Tacon F, Marsit S, Ropars J, Richard F, Selosse M-A (2017) Fungi as a Source of Food. Microbiology Spectrum, 5, 5.3.09. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0030-2016 [2] Legras J-L, Galeote V, Bigey F, Camarasa C, Marsit S, Nidelet T, Sanchez I, Couloux A, Guy J, Franco-Duarte R, Marcet-Houben M, Gabaldon T, Schuller D, Sampaio JP, Dequin S (2018) Adaptation of S. cerevisiae to Fermented Food Environments Reveals Remarkable Genome Plasticity and the Footprints of Domestication. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1712–1727. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy066 [3] Bai F-Y, Han D-Y, Duan S-F, Wang Q-M (2022) The Ecology and Evolution of the Baker’s Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes, 13, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13020230 [4] Fay JC, Benavides JA (2005) Evidence for Domesticated and Wild Populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLOS Genetics, 1, e5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0010005 [5] Ropars J, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, López-Villavicencio M, Gouzy J, Sallet E, Dumas É, Lacoste S, Debuchy R, Dupont J, Branca A, Giraud T (2015) Adaptive Horizontal Gene Transfers between Multiple Cheese-Associated Fungi. Current Biology, 25, 2562–2569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.025 [6] Dumas E, Feurtey A, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Le Prieur S, Snirc A, Coton M, Thierry A, Coton E, Le Piver M, Roueyre D, Ropars J, Branca A, Giraud T (2020) Independent domestication events in the blue-cheese fungus Penicillium roqueforti. Molecular Ecology, 29, 2639–2660. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15359 [7] Ropars J, Didiot E, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Bennetot B, Coton M, Poirier E, Coton E, Snirc A, Le Prieur S, Giraud T (2020) Domestication of the Emblematic White Cheese-Making Fungus Penicillium camemberti and Its Diversification into Two Varieties. Current Biology, 30, 4441-4453.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.082 [8] Caron T, Piver ML, Péron A-C, Lieben P, Lavigne R, Brunel S, Roueyre D, Place M, Bonnarme P, Giraud T, Branca A, Landaud S, Chassard C (2021) Strong effect of Penicillium roqueforti populations on volatile and metabolic compounds responsible for aromas, flavor and texture in blue cheeses. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 354, 109174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109174 [9] Ropars J, Lo Y-C, Dumas E, Snirc A, Begerow D, Rollnik T, Lacoste S, Dupont J, Giraud T, López-Villavicencio M (2016) Fertility depression among cheese-making Penicillium roqueforti strains suggests degeneration during domestication. Evolution, 70, 2099–2109. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13015 [10] Michel E, Masson E, Bubbendorf S, Lapicque L, Nidelet T, Segond D, Guézenec S, Marlin T, Devillers H, Rué O, Onno B, Legrand J, Sicard D, Bakers TP (2022) Artisanal and farmer bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs. bioRxiv, 679472, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/679472 [11] Vavilov NI, Vavylov MI, Dorofeev VF (1992) Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants. Cambridge University Press. [12] Saslis-Lagoudakis CH, Clarke AC (2013) Ethnobiology: the missing link in ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28, 67–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.10.017 [13] Thomas M, Demeulenaere E, Dawson JC, Khan AR, Galic N, Jouanne-Pin S, Remoue C, Bonneuil C, Goldringer I (2012) On-farm dynamic management of genetic diversity: the impact of seed diffusions and seed saving practices on a population-variety of bread wheat. Evolutionary Applications, 5, 779–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-4571.2012.00257.x [14] Demeulenaere É, Lagrola M (2021) Des indicateurs pour accompagner “ les éleveurs de microbes” : Une communauté épistémique face au problème des laits “ paucimicrobiens ” dans la production fromagère au lait cru (1995-2015). Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances, 15. http://journals.openedition.org/rac/24953 | Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs | Elisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Preserving microbial diversity in food systems is one of the many challenges to be met to achieve food security and quality. Although industrialization led to the selection and spread of specific fermenting microbia... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology | Tatiana Giraud | 2022-01-27 14:53:08 | View | |

25 Mar 2019

The joint evolution of lifespan and self-fertilisationThomas Lesaffre, Sylvain Billiard https://doi.org/10.1101/420877Evolution of selfing & lifespan 2.0Recommended by Thomas Bataillon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersFlowering plants display a staggering diversity of both mating systems and life histories, ranging from almost exclusively selfers to obligate outcrossers, very short-lived annual herbs to super long lived trees. One pervasive pattern that has attracted considerable attention is the tight correlation that is found between mating systems and lifespan [1]. Until recently, theoretical explanations for these patterns have relied on static models exploring the consequences of several non-mutually exclusive important process: levels of inbreeding depression and ability to successfully were center stage. This make sense: successful colonization after long‐distance dispersal is far more likely to happen for self‐compatible than for self‐incompatible individuals in a sexually reproducing species. Furthermore, inbreeding depression (essentially a genetically driven phenomenon) and reproductive insurance are expected to shape the evolution of both mating system and lifespan. References | The joint evolution of lifespan and self-fertilisation | Thomas Lesaffre, Sylvain Billiard | <p>In Angiosperms, there exists a strong association between mating system and lifespan. Most self-fertilising species are short-lived and most predominant or obligate outcrossers are long-lived. This association is generally explained by the infl... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Life History, Reproduction and Sex | Thomas Bataillon | 2018-09-19 10:03:51 | View | |

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

A supergene determines highly divergent male reproductive morphs in the ruffKüpper C, Stocks M, Risse JE, dos Remedios N, Farrell LL, McRae SB, Morgan TC, Karlionova N, Pinchuk P, Verkuil YI, et al. doi:10.1038/ng.3443Supergene Control of a Reproductive PolymorphismRecommended by Thomas Flatt and Laurent KellerTwo back-to-back papers published earlier this year in Nature Genetics provide compelling evidence for the control of a male reproductive polymorphism in a wading bird by a "supergene", a cluster of tightly linked genes [1-2]. The bird in question, the ruff (Philomachus pugnax), has a rather unusual reproductive system that consists of three distinct types of males ("reproductive morphs"): aggressive "independents" who represent the majority of males; a smaller fraction of non-territorial "satellites" who are submissive towards "independents"; and "faeders" who mimic females and are rare. Previous work has shown that the male morphs differ in major aspects of mating and aggression behavior, plumage coloration and body size, and that – intriguingly – this complex multi-trait polymorphism is apparently controlled by a single autosomal Mendelian locus with three alleles [3]. To uncover the genetic control of this polymorphism two independent teams, led by Terry Burke [1] and Leif Andersson [2], have set out to analyze the genomes of male ruffs. Using a combination of genomics and genetics, both groups managed to pin down the supergene locus and map it to a non-recombining, 4.5 Mb large inversion which arose 3.8 million years ago. While "independents" are homozygous for the ancestral uninverted sequence, "satellites" and "faeders" carry evolutionarily divergent, dominant alternative haplotypes of the inversion. Thus, as in several other notable cases, for example the supergene control of disassortative mating, aggressiveness and plumage color in white-throated sparrows [4], of mimicry in Heliconius and Papilio butterflies [5-6], or of social structure in ants [7], an inversion – behaving as a single "locus" – underpins the mechanistic basis of the supergene. More generally, and beyond inversions, a growing number of studies now shows that selection can favor the evolution of suppressed recombination, thereby leading to the emergence of clusters of tightly linked loci which can then control – presumably due to polygenic gene action – a suite of complex phenotypes [8-10]. A largely unresolved question in this field concerns the identity of the causative alleles and loci within a given supergene. Recent progress on this question has been made for example in Papilio polytes butterflies where a mimicry supergene has been found to involve – surprisingly – only a single but large gene: multiple mimicry alleles in the doublesex gene are maintained in strong linkage disequilibrium via an inversion. It will clearly be of great interest to see future examples of such a fine-scale genetic dissection of supergenes. In conclusion, we were impressed by the data and analyses of Küpper et al. [1] and Lamichhaney et al. [2]: both papers beautifully illustrate how genomics and evolutionary ecology can be combined to make new, exciting discoveries. Both papers will appeal to readers with an interest in supergenes, inversions, the interplay of selection and recombination, or the genetic control of complex phenotypes. References [1] Küpper C, Stocks M, Risse JE, dos Remedios N, Farrell LL, McRae SB, Morgan TC, Karlionova N, Pinchuk P, Verkuil YI, et al. 2016. A supergene determines highly divergent male reproductive morphs in the ruff. Nature Genetics 48:79-83. doi: 10.1038/ng.3443 [2] Lamichhaney S, Fan G, Widemo F, Gunnarsson U, Thalmann DS, Hoeppner MP, Kerje S, Gustafson U, Shi C, Zhang H, et al. 2016. Structural genomic changes underlie alternative reproductive strategies in the ruff (Philomachus pugnax). Nature Genetics 48:84-88. doi: 10.1038/ng.3430 [3] Lank DB, Smith CM, Hanotte O, Burke T, Cooke F. 1995. Genetic polymorphism for alternative mating behaviour in lekking male ruff Philomachus pugnax. Nature 378:59-62. doi: 10.1038/378059a0 [4] Tuttle Elaina M, Bergland Alan O, Korody Marisa L, Brewer Michael S, Newhouse Daniel J, Minx P, Stager M, Betuel A, Cheviron Zachary A, Warren Wesley C, et al. 2016. Divergence and Functional Degradation of a Sex Chromosome-like Supergene. Current Biology 26:344-350. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.069 [5] Joron M, Frezal L, Jones RT, Chamberlain NL, Lee SF, Haag CR, Whibley A, Becuwe M, Baxter SW, Ferguson L, et al. 2011. Chromosomal rearrangements maintain a polymorphic supergene controlling butterfly mimicry. Nature 477:203-206. doi: 10.1038/nature10341 [6] Kunte K, Zhang W, Tenger-Trolander A, Palmer DH, Martin A, Reed RD, Mullen SP, Kronforst MR. 2014. doublesex is a mimicry supergene. Nature 507:229-232. doi: 10.1038/nature13112 [7] Wang J, Wurm Y, Nipitwattanaphon M, Riba-Grognuz O, Huang Y-C, Shoemaker D, Keller L. 2013. A Y-like social chromosome causes alternative colony organization in fire ants. Nature 493:664-668. doi: 10.1038/nature11832 [8] Thompson MJ, Jiggins CD. 2014. Supergenes and their role in evolution. Heredity 113:1-8. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2014.20 [9] Schwander T, Libbrecht R, Keller L. 2014. Supergenes and Complex Phenotypes. Current Biology 24:R288-R294. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.056 [10] Charlesworth D. 2015. The status of supergenes in the 21st century: recombination suppression in Batesian mimicry and sex chromosomes and other complex adaptations. Evolutionary Applications 9:74-90. doi: 10.1111/eva.12291 | A supergene determines highly divergent male reproductive morphs in the ruff | Küpper C, Stocks M, Risse JE, dos Remedios N, Farrell LL, McRae SB, Morgan TC, Karlionova N, Pinchuk P, Verkuil YI, et al. | Three strikingly different alternative male mating morphs (aggressive 'independents', semicooperative 'satellites' and female-mimic 'faeders') coexist as a balanced polymorphism in the ruff, *Philomachus pugnax*, a lek-breeding wading bird1, 2, 3.... |  | Adaptation, Genotype-Phenotype, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Thomas Flatt | 2016-12-13 17:28:13 | View | |

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Structural genomic changes underlie alternative reproductive strategies in the ruff (Philomachus pugnax)Lamichhaney S, Fan G, Widemo F, Gunnarsson U, Thalmann DS, Hoeppner MP, Kerje S, Gustafson U, Shi C, Zhang H, et al. doi:10.1038/ng.3430Supergene Control of a Reproductive PolymorphismRecommended by Thomas Flatt and Laurent KellerTwo back-to-back papers published earlier this year in Nature Genetics provide compelling evidence for the control of a male reproductive polymorphism in a wading bird by a "supergene", a cluster of tightly linked genes [1-2]. The bird in question, the ruff (Philomachus pugnax), has a rather unusual reproductive system that consists of three distinct types of males ("reproductive morphs"): aggressive "independents" who represent the majority of males; a smaller fraction of non-territorial "satellites" who are submissive towards "independents"; and "faeders" who mimic females and are rare. Previous work has shown that the male morphs differ in major aspects of mating and aggression behavior, plumage coloration and body size, and that – intriguingly – this complex multi-trait polymorphism is apparently controlled by a single autosomal Mendelian locus with three alleles [3]. To uncover the genetic control of this polymorphism two independent teams, led by Terry Burke [1] and Leif Andersson [2], have set out to analyze the genomes of male ruffs. Using a combination of genomics and genetics, both groups managed to pin down the supergene locus and map it to a non-recombining, 4.5 Mb large inversion which arose 3.8 million years ago. While "independents" are homozygous for the ancestral uninverted sequence, "satellites" and "faeders" carry evolutionarily divergent, dominant alternative haplotypes of the inversion. Thus, as in several other notable cases, for example the supergene control of disassortative mating, aggressiveness and plumage color in white-throated sparrows [4], of mimicry in Heliconius and Papilio butterflies [5-6], or of social structure in ants [7], an inversion – behaving as a single "locus" – underpins the mechanistic basis of the supergene. More generally, and beyond inversions, a growing number of studies now shows that selection can favor the evolution of suppressed recombination, thereby leading to the emergence of clusters of tightly linked loci which can then control – presumably due to polygenic gene action – a suite of complex phenotypes [8-10]. A largely unresolved question in this field concerns the identity of the causative alleles and loci within a given supergene. Recent progress on this question has been made for example in Papilio polytes butterflies where a mimicry supergene has been found to involve – surprisingly – only a single but large gene: multiple mimicry alleles in the doublesex gene are maintained in strong linkage disequilibrium via an inversion. It will clearly be of great interest to see future examples of such a fine-scale genetic dissection of supergenes. In conclusion, we were impressed by the data and analyses of Küpper et al. [1] and Lamichhaney et al. [2]: both papers beautifully illustrate how genomics and evolutionary ecology can be combined to make new, exciting discoveries. Both papers will appeal to readers with an interest in supergenes, inversions, the interplay of selection and recombination, or the genetic control of complex phenotypes. References [1] Küpper C, Stocks M, Risse JE, dos Remedios N, Farrell LL, McRae SB, Morgan TC, Karlionova N, Pinchuk P, Verkuil YI, et al. 2016. A supergene determines highly divergent male reproductive morphs in the ruff. Nature Genetics 48:79-83. doi: 10.1038/ng.3443 [2] Lamichhaney S, Fan G, Widemo F, Gunnarsson U, Thalmann DS, Hoeppner MP, Kerje S, Gustafson U, Shi C, Zhang H, et al. 2016. Structural genomic changes underlie alternative reproductive strategies in the ruff (Philomachus pugnax). Nature Genetics 48:84-88. doi: 10.1038/ng.3430 [3] Lank DB, Smith CM, Hanotte O, Burke T, Cooke F. 1995. Genetic polymorphism for alternative mating behaviour in lekking male ruff Philomachus pugnax. Nature 378:59-62. doi: 10.1038/378059a0 [4] Tuttle Elaina M, Bergland Alan O, Korody Marisa L, Brewer Michael S, Newhouse Daniel J, Minx P, Stager M, Betuel A, Cheviron Zachary A, Warren Wesley C, et al. 2016. Divergence and Functional Degradation of a Sex Chromosome-like Supergene. Current Biology 26:344-350. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.069 [5] Joron M, Frezal L, Jones RT, Chamberlain NL, Lee SF, Haag CR, Whibley A, Becuwe M, Baxter SW, Ferguson L, et al. 2011. Chromosomal rearrangements maintain a polymorphic supergene controlling butterfly mimicry. Nature 477:203-206. doi: 10.1038/nature10341 [6] Kunte K, Zhang W, Tenger-Trolander A, Palmer DH, Martin A, Reed RD, Mullen SP, Kronforst MR. 2014. doublesex is a mimicry supergene. Nature 507:229-232. doi: 10.1038/nature13112 [7] Wang J, Wurm Y, Nipitwattanaphon M, Riba-Grognuz O, Huang Y-C, Shoemaker D, Keller L. 2013. A Y-like social chromosome causes alternative colony organization in fire ants. Nature 493:664-668. doi: 10.1038/nature11832 [8] Thompson MJ, Jiggins CD. 2014. Supergenes and their role in evolution. Heredity 113:1-8. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2014.20 [9] Schwander T, Libbrecht R, Keller L. 2014. Supergenes and Complex Phenotypes. Current Biology 24:R288-R294. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.056 [10] Charlesworth D. 2015. The status of supergenes in the 21st century: recombination suppression in Batesian mimicry and sex chromosomes and other complex adaptations. Evolutionary Applications 9:74-90. doi: 10.1111/eva.12291 | Structural genomic changes underlie alternative reproductive strategies in the ruff (Philomachus pugnax) | Lamichhaney S, Fan G, Widemo F, Gunnarsson U, Thalmann DS, Hoeppner MP, Kerje S, Gustafson U, Shi C, Zhang H, et al. | The ruff is a Palearctic wader with a spectacular lekking behavior where highly ornamented males compete for females1, 2, 3, 4. This bird has one of the most remarkable mating systems in the animal kingdom, comprising three different male morphs (... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Thomas Flatt | 2016-12-13 17:46:54 | View | |

15 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Limiting opportunities for cheating stabilizes virulence in insect parasitic nematodesShapiro-Ilan D. and B. Raymond doi:10.1111/eva.12348Application of kin theory to long-standing problem in nematode production for biocontrolRecommended by Thomas Sappington and Ruth Arabelle HufbauerMuch research effort has been extended toward developing systems for managing soil inhabiting insect pests of crops with entomopathogenic nematodes as biocontrol agents. Although small plot or laboratory experiments may suggest a particular insect pest is vulnerable to management in this way, it is often difficult to scale-up nematode production for application at the field- and farm scale to make such a tactic viable. Part of the problem is that entomopathogenic nematode strains must be propagated by serial passage in vivo, because storage by freezing decreases fitness. At the same time, serial propagation results in loss of virulence (ability to infect) over generations in the laboratory, a phenomenon called attenuation. To probe the underlying reasons for development of attenuation, as a prerequisite to designing strategies to mitigate it, Shapiro-Ilan and Raymond [1] turned to evolutionary theory of social conflict as a possible explanatory framework. Virulence of entomopathogenic nematodes depends on a combination of virulence factors, like various proteases, secreted by both the nematode and symbiotic bacteria to overcome host defenses. Attenuation is characterized in part by a reduced production of these factors. Invasion of a host involves simultaneous attack by a group of nematodes ("cooperators"), which together neutralize host defenses enough to allow individuals to successfully invade. "Cheaters" in the invading population can avoid the metabolic costs of producing virulence factors while reaping the benefits of infecting the host made vulnerable by the cooperators in the population. The authors hypothesize that an increase in frequency of cheaters may contribute to attenuation of virulence during serial propagation in the laboratory. The evolutionary dynamics of cheater frequency in a population have been explored in many contexts as part of kin selection theory. Cheaters can increase in a population by outcompeting cooperators in a host if overall relatedness within the invading population is low. Conversely, frequency of altruism, or costly cooperation, increases in a population if relatedness is high, which is enhanced by low effective dispersal. However, a population that is too isolated can suffer from inbreeding effects, and competition will occur mainly among relatives, which decreases the fitness benefits of altruism. Shapiro-Ilan and Raymond [1] tested changes in virulence and reproductive output in a serially propagated entomopathogenic nematode, Heterorhabditis floridensis. They compared lines of high or low relatedness, manipulated via multiplicity of infection (MOI) rates (where a low dose of nematodes gives high relatedness and a high dose gives low relatedness); and under global or local competition, manipulated by pooling populations emerging from all or only two host cadavers per generation, respectively. As predicted, treatments of high relatedness (low MOI) and global competition had the greatest level of reproduction, while all lines of low relatedness (high MOI) evolved decreased reproduction and decreased virulence, which led to extinction. The key finding was that lines in the high relatedness (low MOI) and low (local) competition treatment exhibited the most stable virulence through the 12 generations tested. Thus, to minimize attenuation of virulence while maintaining fitness of recently isolated entomopathogenic nematodes, the authors recommend insect hosts be inoculated with low doses of nematodes from inocula pools from as few cadavers as possible. The application of evolutionary theory, with a clever experimental design, to an important problem in pest management makes this paper particularly noteworthy. Reference [1] Shapiro-Ilan D, Raymond B. 2016. Limiting opportunities for cheating stabilizes virulence in insect parasitic nematodes. Evolutionary Applications 9:462-470. doi: 10.1111/eva.12348 | Limiting opportunities for cheating stabilizes virulence in insect parasitic nematodes | Shapiro-Ilan D. and B. Raymond | Cooperative secretion of virulence factors by pathogens can lead to social conflict when cheating mutants exploit collective secretion, but do not contribute to it. If cheats outcompete cooperators within hosts, this can cause loss of virulence.... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory, Experimental Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Thomas Sappington | 2016-12-15 18:33:39 | View | |

02 May 2023

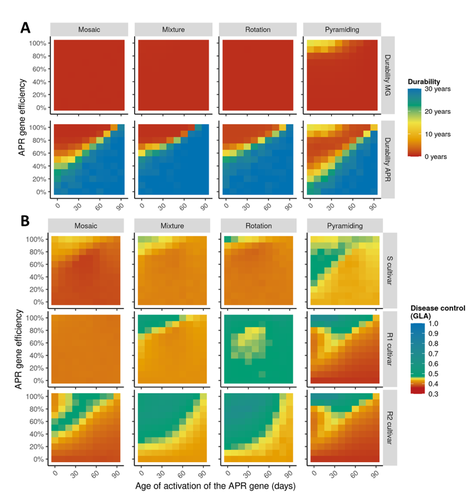

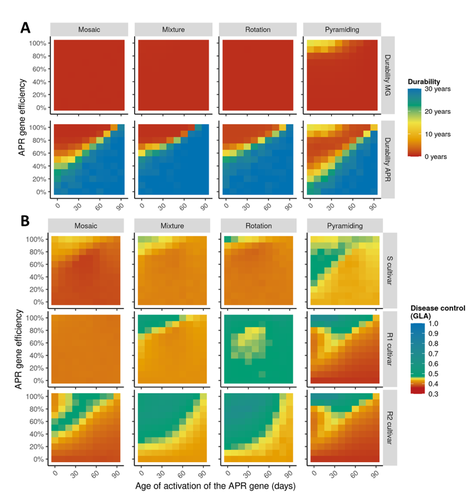

Durable resistance or efficient disease control? Adult Plant Resistance (APR) at the heart of the dilemmaLoup Rimbaud, Julien Papaïx, Jean-François Rey, Benoît Moury, Luke G. Barrett, Peter H. Thrall https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.30.505787Plant resistance to pathogens: just you wait?Recommended by Timothée Poisot based on reviews by Jean-Paul Soularue and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this preprint, Rimbaud et al. (2023) examine whether Adult Plant Resistance (APR), where plants delay their response to pathogens, is a viable alternative when the solution to evolve complete resistance from the seedling stage exists. At first glance, delaying resistance seems like a counter-intuitive strategy, unless it can result in a weaker selection of the pathogen, and therefore slow down its adaption to plant resistance. The approach of Rimbaud et al. is to incorporate as much of the mechanisms as possible into a model. By accounting for explicit spatio-temporal dynamics, stochasticity, and the coupling between demography and population genetics, to simulate an agricultural landscape, they reach a nuanced conclusion. Weaker and delayed activation of genes that confer APR does indeed reduce the selection pressure acting on the pathogen, at the cost of overall less effective protection. The alternative strategy of rapid or complete activation of these genes, although it results in better results in defending against the pathogen, is at risk of being overcome because it introduces a stronger selection pressure. One important feature of this work is that it accounts for agricultural practices. The landscape that is simulated can account for monoculture, mosaic cultures, mixed cultures, and rotations of crops (with different strategies for resistance). This introduces an interesting element to the conclusion: that human practices will have an impact on the selection pressures acting within the system. Perhaps the most striking result is that, for the plants, it might be more beneficial to bear the cost of a wild-type pathogen that can benefit from delayed activation of resistance, and therefore exclude the more virulent strains by simply being there first, and essentially buying the plant some time before it activates its resistance more completely. When the landscape is aggregated, even wild-type pathogens can cause severe epidemics; increasing fragmentation, because it enables connectivity between patches of plants with different strategies, allows pathogens to move across cultivars, and reduces the epidemic risk on susceptible plants. These results should encourage scaling up the perspective on APR, and indeed Rimbaud et al. adopt a landscape-scale perspective, to show that APR genes and genes conferring more complete resistance early on can have synergistic effects. This is, again, both an interesting result for evolutionary biologists, but also a useful way to prioritize different crop management strategies over large spatial scales. References Rimbaud, Loup, et al. Durable Resistance or Efficient Disease Control? Adult Plant Resistance (APR) at the Heart of the Dilemma. 2023. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.30.505787 | Durable resistance or efficient disease control? Adult Plant Resistance (APR) at the heart of the dilemma | Loup Rimbaud, Julien Papaïx, Jean-François Rey, Benoît Moury, Luke G. Barrett, Peter H. Thrall | <p style="text-align: justify;">Adult plant resistance (APR) is an incomplete and delayed protection of plants against pathogens. At first glance, such resistance should be less efficient than classical major-effect resistance genes, which confer ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Timothée Poisot | 2022-09-02 16:36:32 | View | |

06 Apr 2021

How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans?Alba Refoyo-Martínez, Siyang Liu, Anja Moltke Jørgensen, Xin Jin, Anders Albrechtsen, Alicia R. Martin, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.13.200030Be careful when studying selection based on polygenic score overdispersionRecommended by Torsten Günther based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio, Mashaal Sohail, Barbara Bitarello and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio, Mashaal Sohail, Barbara Bitarello and 1 anonymous reviewer

The advent of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) has been a great promise for our understanding of the connection between genotype and phenotype. Today, the NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog contains 251,401 associations from 4,961 studies (1). This wealth of studies has also generated interest to use the summary statistics beyond the few top hits in order to make predictions for individuals without known phenotype, e.g. to predict polygenic risk scores or to study polygenic selection by comparing different groups. For instance, polygenic selection acting on the most studied polygenic trait, height, has been subject to multiple studies during the past decade (e.g. 2–6). They detected north-south gradients in Europe which were consistent with expectations. However, their GWAS summary statistics were based on the GIANT consortium data set, a meta-analysis of GWAS conducted in different European cohorts (7,8). The availability of large data sets with less stratification such as the UK Biobank (9) has led to a re-evaluation of those results. The nature of the GIANT consortium data set was realized to represent a potential problem for studies of polygenic adaptation which led several of the authors of the original articles to caution against the interpretations of polygenic selection on height (10,11). This was a great example on how the scientific community assessed their own earlier results in a critical way as more data became available. At the same time it left the question whether there is detectable polygenic selection separating populations more open than ever. Generally, recent years have seen several articles critically assessing the portability of GWAS results and risk score predictions to other populations (12–14). Refoyo-Martínez et al. (15) are now presenting a systematic assessment on the robustness of cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans. They compiled GWAS results for complex traits which have been studied in more than one cohort and then use allele frequencies from the 1000 Genomes Project data (16) set to detect signals of polygenic score overdispersion. As the source for the allele frequencies is kept the same across all tests, differences between the signals must be caused by the underlying GWAS. The results are concerning as the level of overdispersion largely depends on the choice of GWAS cohort. Cohorts with homogenous ancestries show little to no overdispersion compared to cohorts of mixed ancestries such as meta-analyses. It appears that the meta-analyses fail to fully account for stratification in their data sets. The authors based most of their analyses on the heavily studied trait height. Additionally, they use educational attainment (measured as the number of school years of an individual) as an example. This choice was due to the potential over- or misinterpretation of results by the media, the general public and by far right hate groups. Such traits are potentially confounded by unaccounted cultural and socio-economic factors. Showing that previous results about polygenic selection on educational attainment are not robust is an important result that needs to be communicated well. This forms a great example for everyone working in human genomics. We need to be aware that our results can sometimes be misinterpreted. And we need to make an effort to write our papers and communicate our results in a way that is honest about the limitations of our research and that prevents the misuse of our results by hate groups. This article represents an important contribution to the field. It is cruicial to be aware of potential methodological biases and technical artifacts. Future studies of polygenic adaptation need to be cautious with their interpretations of polygenic score overdispersion. A recommendation would be to use GWAS results obtained in homogenous cohorts. But even if different biobank-scale cohorts of homogeneous ancestry are employed, there will always be some remaining risk of unaccounted stratification. These conclusions may seem sobering but they are part of the scientific process. We need additional controls and new, different methods than polygenic score overdispersion for assessing polygenic selection. Last year also saw the presentation of a novel approach using sequence data and GWAS summary statistics to detect directional selection on a polygenic trait (17). This new method appears to be robust to bias stemming from stratification in the GWAS cohort as well as other confounding factors. Such new developments show light at the end of the tunnel for the use of GWAS summary statistics in the study of polygenic adaptation. References 1. Buniello A, MacArthur JAL, Cerezo M, Harris LW, Hayhurst J, Malangone C, et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019 Jan 8;47(D1):D1005–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1120 2. Turchin MC, Chiang CW, Palmer CD, Sankararaman S, Reich D, Hirschhorn JN. Evidence of widespread selection on standing variation in Europe at height-associated SNPs. Nature Genetics. 2012 Sep;44(9):1015–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2368 3. Berg JJ, Coop G. A Population Genetic Signal of Polygenic Adaptation. PLOS Genetics. 2014 Aug 7;10(8):e1004412. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004412 4. Robinson MR, Hemani G, Medina-Gomez C, Mezzavilla M, Esko T, Shakhbazov K, et al. Population genetic differentiation of height and body mass index across Europe. Nature Genetics. 2015 Nov;47(11):1357–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3401 5. Mathieson I, Lazaridis I, Rohland N, Mallick S, Patterson N, Roodenberg SA, et al. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature. 2015 Dec;528(7583):499–503. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16152 6. Racimo F, Berg JJ, Pickrell JK. Detecting polygenic adaptation in admixture graphs. Genetics. 2018. Arp;208(4):1565–1584. doi: https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.117.300489 7. Lango Allen H, Estrada K, Lettre G, Berndt SI, Weedon MN, Rivadeneira F, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010 Oct;467(7317):832–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09410 8. Wood AR, Esko T, Yang J, Vedantam S, Pers TH, Gustafsson S, et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nat Genet. 2014 Nov;46(11):1173–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3097 9. Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018 Oct;562(7726):203–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z 10. Berg JJ, Harpak A, Sinnott-Armstrong N, Joergensen AM, Mostafavi H, Field Y, et al. Reduced signal for polygenic adaptation of height in UK Biobank. eLife. 2019 Mar 21;8:e39725. doi: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.39725 11. Sohail M, Maier RM, Ganna A, Bloemendal A, Martin AR, Turchin MC, et al. Polygenic adaptation on height is overestimated due to uncorrected stratification in genome-wide association studies. eLife. 2019 Mar 21;8:e39702. doi: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.39702 12. Martin AR, Kanai M, Kamatani Y, Okada Y, Neale BM, Daly MJ. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nature Genetics. 2019 Apr;51(4):584–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0379-x 13. Bitarello BD, Mathieson I. Polygenic Scores for Height in Admixed Populations. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 2020 Nov 1;10(11):4027–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.120.401658 14. Uricchio LH, Kitano HC, Gusev A, Zaitlen NA. An evolutionary compass for detecting signals of polygenic selection and mutational bias. Evolution Letters. 2019;3(1):69–79. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.97 15. Refoyo-Martínez A, Liu S, Jørgensen AM, Jin X, Albrechtsen A, Martin AR, Racimo F. How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans? bioRxiv, 2021, 2020.07.13.200030, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Evolutionary Biology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.13.200030 16. Auton A, Abecasis GR, Altshuler DM, Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Bentley DR, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015 Sep 30;526(7571):68–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15393 17. Stern AJ, Speidel L, Zaitlen NA, Nielsen R. Disentangling selection on genetically correlated polygenic traits using whole-genome genealogies. bioRxiv. 2020 May 8;2020.05.07.083402. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.07.083402 | How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans? | Alba Refoyo-Martínez, Siyang Liu, Anja Moltke Jørgensen, Xin Jin, Anders Albrechtsen, Alicia R. Martin, Fernando Racimo | <p>Over the past decade, summary statistics from genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have been used to detect and quantify polygenic adaptation in humans. Several studies have reported signatures of natural selection at sets of SNPs associated... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genetic conflicts, Human Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Torsten Günther | 2020-08-14 15:06:54 | View | |

25 Feb 2021

Alteration of gut microbiota with a broad-spectrum antibiotic does not impair maternal care in the European earwigSophie Van Meyel, Séverine Devers, Simon Dupont, Franck Dedeine and Joël Meunier https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.08.331363Assessing the role of host-symbiont interactions in maternal care behaviourRecommended by Trine Bilde based on reviews by Nadia Aubin-Horth, Gabrielle Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nadia Aubin-Horth, Gabrielle Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer

The role of microbial symbionts in governing social traits of their hosts is an exciting and developing research area. Just like symbionts influence host reproductive behaviour and can cause mating incompatibilities to promote symbiont transmission through host populations (Engelstadter and Hurst 2009; Correa and Ballard 2016; Johnson and Foster 2018) (see also discussion on conflict resolution in Johnsen and Foster 2018), microbial symbionts could enhance transmission by promoting the social behaviour of their hosts (Ezenwa et al. 2012; Lewin-Epstein et al. 2017; Gurevich et al. 2020). Here I apply the term ‘symbiosis’ in the broad sense, following De Bary 1879 as “the living together of two differently named organisms“ independent of effects on the organisms involved (De Bary 1879), i.e. the biological interaction between the host and its symbionts may include mutualism, parasitism and commensalism. References Correa, C. C., and Ballard, J. W. O. (2016). Wolbachia associations with insects: winning or losing against a master manipulator. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 3, 153. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2015.00153 De Bary, A. (1879). Die Erscheinung der Symbiose. Verlag von Karl J. Trubner, Strassburg. Engelstädter, J., and Hurst, G. D. (2009). The ecology and evolution of microbes that manipulate host reproduction. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 40, 127-149. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120206 Ezenwa, V. O., Gerardo, N. M., Inouye, D. W., Medina, M., and Xavier, J. B. (2012). Animal behavior and the microbiome. Science, 338(6104), 198-199. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1227412 Gurevich, Y., Lewin-Epstein, O., and Hadany, L. (2020). The evolution of paternal care: a role for microbes?. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 375(1808), 20190599. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0599 Hird, S. M. (2017). Evolutionary biology needs wild microbiomes. Frontiers in microbiology, 8, 725. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00725 Johnson, K. V. A., and Foster, K. R. (2018). Why does the microbiome affect behaviour?. Nature reviews microbiology, 16(10), 647-655. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0014-3 Kramer et al. (2017). When earwig mothers do not care to share: parent–offspring competition and the evolution of family life. Functional Ecology, 31(11), 2098-2107. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12915 Lewin-Epstein, O., Aharonov, R., and Hadany, L. (2017). Microbes can help explain the evolution of host altruism. Nature communications, 8(1), 1-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14040 Meunier, J., and Kölliker, M. (2012). Parental antagonism and parent–offspring co-adaptation interact to shape family life. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279(1744), 3981-3988. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.1416 Meunier, J., Wong, J. W., Gómez, Y., Kuttler, S., Röllin, L., Stucki, D., and Kölliker, M. (2012). One clutch or two clutches? Fitness correlates of coexisting alternative female life-histories in the European earwig. Evolutionary Ecology, 26(3), 669-682. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-011-9510-x Nalepa, C. A. (2020). Origin of mutualism between termites and flagellated gut protists: transition from horizontal to vertical transmission. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 8, 14. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00014 Ratz, T., Kramer, J., Veuille, M., and Meunier, J. (2016). The population determines whether and how life-history traits vary between reproductive events in an insect with maternal care. Oecologia, 182(2), 443-452. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-016-3685-3 Van Meyel, S., Devers, S., Dupont, S., Dedeine, F. and Meunier, J. (2021) Alteration of gut microbiota with a broad-spectrum antibiotic does not impair maternal care in the European earwig. bioRxiv, 2020.10.08.331363. ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.08.331363 | Alteration of gut microbiota with a broad-spectrum antibiotic does not impair maternal care in the European earwig | Sophie Van Meyel, Séverine Devers, Simon Dupont, Franck Dedeine and Joël Meunier | <p>The microbes residing within the gut of an animal host often increase their own fitness by modifying their host’s physiological, reproductive, and behavioural functions. Whereas recent studies suggest that they may also shape host sociality and... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Life History, Species interactions | Trine Bilde | 2020-10-09 14:07:47 | View | |

01 Sep 2021

Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail speciesJarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242Determinants of population genetic structure in co-occurring freshwater snailsRecommended by Trine Bilde and Matteo Fumagalli and Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Genetic diversity is a key aspect of biodiversity and has important implications for evolutionary potential and thereby the persistence of species. Improving our understanding of the factors that drive genetic structure within and between populations is, therefore, a long-standing goal in evolutionary biology. However, this is a major challenge, because of the complex interplay between genetic drift, migration, and extinction/colonization dynamics on the one hand, and the biology and ecology of species on the other hand (Romiguier et al. 2014, Ellegren and Galtier 2016, Charlesworth 2003). Jarne et al. (2021) studied whether environmental and demographic factors affect the population genetic structure of four species of hermaphroditic freshwater snails in a similar way, using comparative analyses of neutral genetic microsatellite markers. Specifically, they investigated microsatellite variability of Hygrophila in almost 280 sites in Guadeloupe, Lesser Antilles, as part of a long-term survey experiment (Lamy et al. 2013). They then modelled the influence of the mating system, local environmental characteristics and demographic factors on population genetic diversity. Consistent with theoretical predictions (Charlesworth 2003), they detected higher genetic variation in two outcrossing species than in two selfing species, emphasizing the importance of the mating system in maintaining genetic diversity. The study further identified an important role of site connectivity, through its influences on effective population size and extinction/colonisation events. Finally, the study detects an influence of interspecific interactions caused by an ongoing invasion by one of the studied species on genetic structure, highlighting the indirect effect of changes in community composition and demography on population genetics. Jarne et al. (2021) could address the extent to which genetic structure is determined by demographic and environmental factors in multiple species given the remarkable sampling available. Additionally, the study system is extremely suitable to address this hypothesis as species’ habitats are defined and delineated. Whilst the authors did attempt to test for across-species correlations, further investigations on this matter are required. Moreover, the effect of interactions between factors should be appropriately considered in any modelling between genetic structure and local environmental or demographic features. The findings in this study contribute to improving our understanding of factors influencing population genetic diversity, and highlights the complexity of interacting factors, therefore also emphasizing the challenges of drawing general implications, additionally hampered by the relatively limited number of species studied. Jarne et al. (2021) provide an excellent showcase of an empirical framework to test determinants of genetic structure in natural populations. As such, this study can be an example for further attempts of comparative analysis of genetic diversity. References Charlesworth, D. (2003) Effects of inbreeding on the genetic diversity of populations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358, 1051-1070. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2003.1296 Ellegren, H. and Galtier, N. (2016) Determinants of genetic diversity. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17, 422-433. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.58 Jarne, P., Lozano del Campo, A., Lamy, T., Chapuis, E., Dubart, M., Segard, A., Canard, E., Pointier, J.-P. and David, P. (2021) Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species. HAL, hal-03295242, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242 Lamy, T., Gimenez, O., Pointier, J. P., Jarne, P. and David, P. (2013). Metapopulation dynamics of species with cryptic life stages. The American Naturalist, 181, 479-491. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/669676 Romiguier, J., Gayral, P., Ballenghien, M. et al. (2014) Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature, 515, 261-263. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13685 | Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species | Jarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. | <p style="text-align: justify;">The distribution of neutral genetic variation in subdivided populations is driven by the interplay between genetic drift, migration, local extinction and colonization. The influence of environmental and demographic ... | Adaptation, Evolutionary Dynamics, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Trine Bilde | 2021-02-11 19:57:51 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer