Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors▼ | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

03 Oct 2023

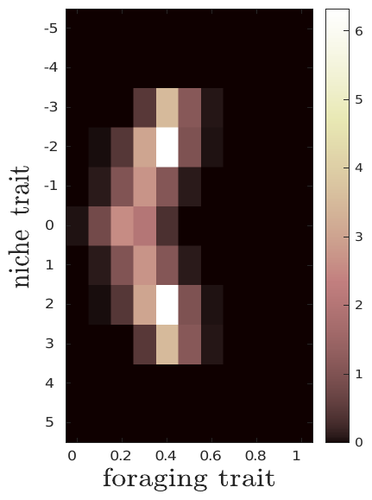

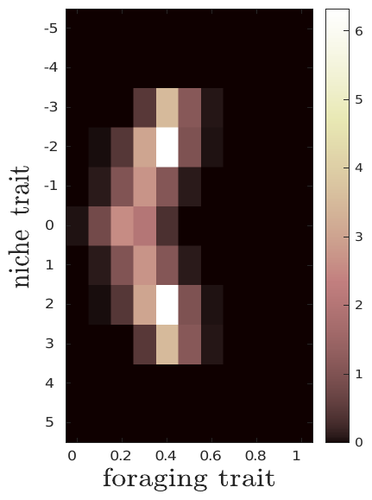

The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer modelLéo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Océane Guillot, Erwan Faou, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Ibanez https://doi.org/10.32942/X2QG7MEvolution and consequences of plastic foraging behavior in consumer-resource ecosystemsRecommended by François Rousset based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersPlastic responses of organisms to their environment may be maladaptive in particular when organisms are exposed to new environments. Phenotypic plasticity may also have opposite effects on the adaptive response of organisms to environmental changes: whether phenotypic plasticity favors or hinders such adaptation depends on a balance between the ability of the population to respond to the change non-genetically in the short term, and the weakened genetic response to environmental change. These topics have received continued attention, particularly in the context of climate change (e.g., Chevin et al. 2013, Duputié et al., 2015, Vinton et al . 2022). In their work, Ledru et al. focus on the adaptive nature of plastic behavior and on its consequences in a consumer-resource ecosystem. As they emphasize, previous works have found that plastic foraging promotes community stability, but these did not consider plasticity as an evolving trait, so Ledru et al. set out to test whether this conclusion holds when both plastic foraging and niche traits of consumers and resources evolve (though ultimately, their new conclusions may not all depend on plasticity evolving). Along the way, they first seek to clarify when such plasticity will evolve, and how it affects the evolution of the niche diversity of consumers and resources, before turning to the question of consumer persistence. The model is rather complex, as three traits are allowed to evolve, and the resource uptake expressed through plastic behavior has its own dynamics affected by some form of social learning. Classically, in models of niche evolution, a consumer's efficiency in exploiting a resource characterized by a trait y (here, the resource's individual niche trait), has been described in terms of location-scale (typically Gaussian) kernels, with mean x (the consumer's individual niche trait) specifying the most efficiently exploited resource, and with variance characterizing individual niche breadth. The evolution of the variance has been considered in some previous models but is assumed to be fixed here. Rather, the new model considers the evolution of the distribution of resource traits, of the consumer's individual niche trait (which is not plastic), and of a "plastic foraging trait" that controls the relative time spent foraging plastically versus foraging randomly. When foraging plastically, the consumers modify their foraging effort towards the type of resource that maximizes their energy intake. in some previous models, the effect of variation in the extent of plastic foraging was already considered, but the evolution of allocation to a plastic foraging strategy versus random foraging was not considered. The model is formulated through reaction-diffusion equations, and its dynamics is investigated by numerical integration. Foraging plasticity readily evolves, when resources vary widely enough, competition for resources is strong, and the cost of plasticity is weak. This means in particular that a large individual niche width of consumers selects for increased plastic foraging, as the evolution of plastic foraging leads to reduced niche overlap between consumers. The evolution of plastic foraging itself generally, though not always, favors the diversification of the niche traits of consumers and of resources. There is thus a positive feedback loop between plastic foraging and resource diversity. Ledru et al. conclude that the total niche width of the consumer population should also correlate with the evolution of plastic foraging, an implication which they relate to the so-called niche variation hypothesis and to empirical tests of it. The joint evolution of the consumer's individual niche trait and plastic foraging trait generates a striking pattern within populations: consumers whose individual niche trait is at an edge of the resource distribution forage more plastically. The authors observe that this relatively simple prediction has not been subjected to any empirical test. Returning to the question of consumer persistence, Ledru et al. evaluate this persistence when consumer mortality increases, and in response to either gradual or sudden environmental changes. These different perturbations all reduce the benefits of plastic foraging. The effect of plastic foraging on stability are complex, being negative or positive effect depending on the type of disturbance, and in particular the ecosystem has a lower sustainable rate of environmental change in the presence of plastic foraging. However, allowing the evolutionary regression of plastic foraging then has a comparatively positive effect on persistence. Despite the substantial effort devoted to analyzing this complex model, relaxing some of its assumptions would likely reveal further complexities. Notably, the overall effect of plasticity on consumer persistence depends on effects already encountered in models of the adaptive response of single species to environmental change: a fast non-genetic response in the short term versus a weakened genetic response in the longer term. The overall balance between these opposite effects on adaptation may be difficult to predict robustly. In the case of a constant rate of environmental change, the results of the present model depend on a lag load between the trait changes of consumer and resource populations, and the extent of the lag may also depend on many factors, such as the extent of genetic variation (e.g., Bürger & Lynch, 1995) for niche traits in consumers and resources. Here, the same variance of mutational effects was assumed for all three evolving traits. Further, spatial environmental variation, a central issue in studies of adaptive responses to environmental changes (e.g., Parmesan, 2006, Zhu et al., 2012), was not considered. Finally, the rate of adjustment of effort by consumers with given niche trait and plastic foraging trait values was assumed proportional to the density of consumers with such trait values. This was justified as a way of accounting for the use of social cues during foraging, but to the extent that they occur, social effects could manifest themselves through other learning dynamics. In conclusion, Ledru et al. have addressed a broad range of questions, suggesting new empirical tests of behavioural patterns on one side, and recovering in the context of community response to environmental changes a complexity that could be expected from earlier works on adaptive responses of organisms but that has been overlooked by previous works on community effects of phenotypic plasticity. References Bürger, R. and Lynch, M. (1995), Evolution and extinction in a changing environment: a quantitative-genetic analysis. Evolution, 49: 151-163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1995.tb05967.x Chevin, L.-M., Collins, S. and Lefèvre, F. (2013), Phenotypic plasticity and evolutionary demographic responses to climate change: taking theory out to the field. Funct Ecol, 27: 967-979. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02043.x Duputié, A., Rutschmann, A., Ronce, O. and Chuine, I. (2015), Phenological plasticity will not help all species adapt to climate change. Glob Change Biol, 21: 3062-3073. https://doi-org.inee.bib.cnrs.fr/10.1111/gcb.12914 Ledru, L., Garnier, J., Guillot, O., Faou, E., & Ibanez, S. (2023). The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer model. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2QG7M Parmesan, C. (2006) Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change Vinton, A.C., Gascoigne, S.J.L., Sepil, I., Salguero-Gómez, R., (2022) Plasticity’s role in adaptive evolution depends on environmental change components. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 37: 1067-1078. Zhu, K., Woodall, C.W. and Clark, J.S. (2012), Failure to migrate: lack of tree range expansion in response to climate change. Glob Change Biol, 18: 1042-1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02571.x | The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer model | Léo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Océane Guillot, Erwan Faou, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Ibanez | <p style="text-align: justify;">Phenotypic plasticity has important ecological and evolutionary consequences. In particular, behavioural phenotypic plasticity such as plastic foraging (PF) by consumers, may enhance community stability. Yet little ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | François Rousset | 2023-03-25 12:04:08 | View | |

11 Jul 2022

Mutualists construct the ecological conditions that trigger the transition from parasitismLeo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Matthias Rohr, Camille Nous, Sebastien Ibanez https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.08.18.456759Give them some space: how spatial structure affects the evolutionary transition towards mutualistic symbiosisRecommended by Francois Massol based on reviews by Eva Kisdi and 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Eva Kisdi and 3 anonymous reviewers

The evolution of mutualistic symbiosis is a puzzle that has fascinated evolutionary ecologist for quite a while. Data on transitions between symbiotic bacterial ways of life has evidenced shifts from mutualism towards parasitism and vice versa (Sachs et al., 2011), so there does not seem to be a strong determinism on those transitions. From the host’s perspective, mutualistic symbiosis implies at the very least some form of immune tolerance, which can be costly (e.g. Sorci, 2013). Empirical approaches thus raise very important questions: How can symbiosis turn from parasitism into mutualism when it seemingly needs such a strong alignment of selective pressures on both the host and the symbiont? And yet why is mutualistic symbiosis so widespread and so important to the evolution of macro-organisms (Margulis, 1998)? While much of the theoretical literature on the evolution of symbiosis and mutualism has focused on either the stability of such relationships when non-mutualists can invade the host-symbiont system (e.g. Ferrière et al., 2007) or the effect of the mode of symbiont transmission on the evolutionary dynamics of mutualism (e.g. Genkai-Kato and Yamamura, 1999), the question remains whether and under which conditions parasitic symbiosis can turn into mutualism in the first place. Earlier results suggested that spatial demographic heterogeneity between host populations could be the leading determinant of evolution towards mutualism or parasitism (Hochberg et al., 2000). Here, Ledru et al. (2022) investigate this question in an innovative way by simulating host-symbiont evolutionary dynamics in a spatially explicit context. Their hypothesis is intuitive but its plausibility is difficult to gauge without a model: Does the evolution towards mutualism depend on the ability of the host and symbiont to evolve towards close-range dispersal in order to maintain clusters of efficient host-symbiont associations, thus outcompeting non-mutualists? I strongly recommend reading this paper as the results obtained by the authors are very clear: competition strength and the cost of dispersal both affect the likelihood of the transition from parasitism to mutualism, and once mutualism has set in, symbiont trait values clearly segregate between highly dispersive parasites and philopatric mutualists. The demonstration of the plausibility of their hypothesis is accomplished with brio and thoroughness as the authors also examine the conditions under which the transition can be reversed, the impact of the spatial range of competition and the effect of mortality. Since high dispersal cost and strong, long-range competition appear to be the main factors driving the evolutionary transition towards mutualistic symbiosis, now is the time for empiricists to start investigating this question with spatial structure in mind. References Ferrière, R., Gauduchon, M. and Bronstein, J. L. (2007) Evolution and persistence of obligate mutualists and exploiters: competition for partners and evolutionary immunization. Ecology Letters, 10, 115-126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.01008.x Genkai-Kato, M. and Yamamura, N. (1999) Evolution of mutualistic symbiosis without vertical transmission. Theoretical Population Biology, 55, 309-323. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.1998.1407 Hochberg, M. E., Gomulkiewicz, R., Holt, R. D. and Thompson, J. N. (2000) Weak sinks could cradle mutualistic symbioses - strong sources should harbour parasitic symbioses. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 13, 213-222. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1420-9101.2000.00157.x Ledru L, Garnier J, Rohr M, Noûs C and Ibanez S (2022) Mutualists construct the ecological conditions that trigger the transition from parasitism. bioRxiv, 2021.08.18.456759, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.18.456759 Margulis, L. (1998) Symbiotic planet: a new look at evolution, Basic Books, Amherst. Sachs, J. L., Skophammer, R. G. and Regus, J. U. (2011) Evolutionary transitions in bacterial symbiosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 10800-10807. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100304108 Sorci, G. (2013) Immunity, resistance and tolerance in bird–parasite interactions. Parasite Immunology, 35, 350-361. https://doi.org/10.1111/pim.12047 | Mutualists construct the ecological conditions that trigger the transition from parasitism | Leo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Matthias Rohr, Camille Nous, Sebastien Ibanez | <p>The evolution of mutualism between hosts and initially parasitic symbionts represents a major transition in evolution. Although vertical transmission of symbionts during host reproduction and partner control both favour the stability of mutuali... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Francois Massol | 2021-08-20 12:25:40 | View | |

23 Jun 2021

Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic driftLaurène Gay, Julien Dhinaut, Margaux Jullien, Renaud Vitalis, Miguel Navascués, Vincent Ranwez, and Joëlle Ronfort https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261230Separating adaptation from drift: A cautionary tale from a self-fertilizing plantRecommended by Christoph Haag based on reviews by Pierre Olivier Cheptou, Jon Agren and Stefan LaurentIn recent years many studies have documented shifts in phenology in response to climate change, be it in arrival times in migrating birds, budset in trees, adult emergence in butterflies, or flowering time in annual plants (Coen et al. 2018; Piao et al. 2019). While these changes are, in part, explained by phenotypic plasticity, more and more studies find that they involve also genetic changes, that is, they involve evolutionary change (e.g., Metz et al. 2020). Yet, evolutionary change may occur through genetic drift as well as selection. Therefore, in order to demonstrate adaptive evolutionary change in response to climate change, drift has to be excluded as an alternative explanation (Hansen et al. 2012). A new study by Gay et al. (2021) shows just how difficult this can be. The authors investigated a recent evolutionary shift in flowering time by in a population an annual plant that reproduces predominantly by self-fertilization. The population has recently been subjected to increased temperatures and reduced rainfalls both of which are believed to select for earlier flowering times. They used a “resurrection” approach (Orsini et al. 2013; Weider et al. 2018): Genotypes from the past (resurrected from seeds) were compared alongside more recent genotypes (from more recently collected seeds) under identical conditions in the greenhouse. Using an experimental design that replicated genotypes, eliminated maternal effects, and controlled for microenvironmental variation, they found said genetic change in flowering times: Genotypes obtained from recently collected seeds flowered significantly (about 2 days) earlier than those obtained 22 generations before. However, neutral markers (microsatellites) also showed strong changes in allele frequencies across the 22 generations, suggesting that effective population size, Ne, was low (i.e., genetic drift was strong), which is typical for highly self-fertilizing populations. In addition, several multilocus genotypes were present at high frequencies and persisted over the 22 generations, almost as in clonal populations (e.g., Schaffner et al. 2019). The challenge was thus to evaluate whether the observed evolutionary change was the result of an adaptive response to selection or may be explained by drift alone. Here, Gay et al. (2021) took a particularly careful and thorough approach. First, they carried out a selection gradient analysis, finding that earlier-flowering plants produced more seeds than later-flowering plants. This suggests that, under greenhouse conditions, there was indeed selection for earlier flowering times. Second, investigating other populations from the same region (all populations are located on the Mediterranean island of Corsica, France), they found that a concurrent shift to earlier flowering times occurred also in these populations. Under the hypothesis that the populations can be regarded as independent replicates of the evolutionary process, the observation of concurrent shifts rules out genetic drift (under drift, the direction of change is expected to be random). The study may well have stopped here, concluding that there is good evidence for an adaptive response to selection for earlier flowering times in these self-fertilizing plants, at least under the hypothesis that selection gradients estimated in the greenhouse are relevant to field conditions. However, the authors went one step further. They used the change in the frequencies of the multilocus genotypes across the 22 generations as an estimate of realized fitness in the field and compared them to the phenotypic assays from the greenhouse. The results showed a tendency for high-fitness genotypes (positive frequency changes) to flower earlier and to produce more seeds than low-fitness genotypes. However, a simulation model showed that the observed correlations could be explained by drift alone, as long as Ne is lower than ca. 150 individuals. The findings were thus consistent with an adaptive evolutionary change in response to selection, but drift could only be excluded as the sole explanation if the effective population size was large enough. The study did provide two estimates of Ne (19 and 136 individuals, based on individual microsatellite loci or multilocus genotypes, respectively), but both are problematic. First, frequency changes over time may be influenced by the presence of a seed bank or by immigration from a genetically dissimilar population, which may lead to an underestimation of Ne (Wang and Whitlock 2003). Indeed, the low effective size inferred from the allele frequency changes at microsatellite loci appears to be inconsistent with levels of genetic diversity found in the population. Moreover, high self-fertilization reduces effective recombination and therefore leads to non-independence among loci. This lowers the precision of the Ne estimates (due to a higher sampling variance) and may also violate the assumption of neutrality due to the possibility of selection (e.g., due to inbreeding depression) at linked loci, which may be anywhere in the genome in case of high degrees of self-fertilization. There is thus no definite answer to the question of whether or not the observed changes in flowering time in this population were driven by selection. The study sets high standards for other, similar ones, in terms of thoroughness of the analyses and care in interpreting the findings. It also serves as a very instructive reminder to carefully check the assumptions when estimating neutral expectations, especially when working on species with complicated demographies or non-standard life cycles. Indeed the issues encountered here, in particular the difficulty of establishing neutral expectations in species with low effective recombination, may apply to many other species, including partially or fully asexual ones (Hartfield 2016). Furthermore, they may not be limited to estimating Ne but may also apply, for instance, to the establishment of neutral baselines for outlier analyses in genome scans (see e.g, Orsini et al. 2012). References Cohen JM, Lajeunesse MJ, Rohr JR (2018) A global synthesis of animal phenological responses to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 8, 224–228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0067-3 Gay L, Dhinaut J, Jullien M, Vitalis R, Navascués M, Ranwez V, Ronfort J (2021) Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic drift. bioRxiv, 2020.08.21.261230, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261230 Hansen MM, Olivieri I, Waller DM, Nielsen EE (2012) Monitoring adaptive genetic responses to environmental change. Molecular Ecology, 21, 1311–1329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05463.x Hartfield M (2016) Evolutionary genetic consequences of facultative sex and outcrossing. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 29, 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12770 Metz J, Lampei C, Bäumler L, Bocherens H, Dittberner H, Henneberg L, Meaux J de, Tielbörger K (2020) Rapid adaptive evolution to drought in a subset of plant traits in a large-scale climate change experiment. Ecology Letters, 23, 1643–1653. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13596 Orsini L, Schwenk K, De Meester L, Colbourne JK, Pfrender ME, Weider LJ (2013) The evolutionary time machine: using dormant propagules to forecast how populations can adapt to changing environments. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28, 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2013.01.009 Orsini L, Spanier KI, Meester LD (2012) Genomic signature of natural and anthropogenic stress in wild populations of the waterflea Daphnia magna: validation in space, time and experimental evolution. Molecular Ecology, 21, 2160–2175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05429.x Piao S, Liu Q, Chen A, Janssens IA, Fu Y, Dai J, Liu L, Lian X, Shen M, Zhu X (2019) Plant phenology and global climate change: Current progresses and challenges. Global Change Biology, 25, 1922–1940. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14619 Schaffner LR, Govaert L, De Meester L, Ellner SP, Fairchild E, Miner BE, Rudstam LG, Spaak P, Hairston NG (2019) Consumer-resource dynamics is an eco-evolutionary process in a natural plankton community. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3, 1351–1358. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0960-9 Wang J, Whitlock MC (2003) Estimating Effective Population Size and Migration Rates From Genetic Samples Over Space and Time. Genetics, 163, 429–446. PMID: 12586728 Weider LJ, Jeyasingh PD, Frisch D (2018) Evolutionary aspects of resurrection ecology: Progress, scope, and applications—An overview. Evolutionary Applications, 11, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12563 | Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic drift | Laurène Gay, Julien Dhinaut, Margaux Jullien, Renaud Vitalis, Miguel Navascués, Vincent Ranwez, and Joëlle Ronfort | <p style="text-align: justify;">Resurrection studies are a useful tool to measure how phenotypic traits have changed in populations through time. If these traits modifications correlate with the environmental changes that occurred during the time ... | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Genotype-Phenotype, Phenotypic Plasticity, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Christoph Haag | 2020-08-21 17:26:59 | View | ||

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Structural genomic changes underlie alternative reproductive strategies in the ruff (Philomachus pugnax)Lamichhaney S, Fan G, Widemo F, Gunnarsson U, Thalmann DS, Hoeppner MP, Kerje S, Gustafson U, Shi C, Zhang H, et al. doi:10.1038/ng.3430Supergene Control of a Reproductive PolymorphismRecommended by Thomas Flatt and Laurent KellerTwo back-to-back papers published earlier this year in Nature Genetics provide compelling evidence for the control of a male reproductive polymorphism in a wading bird by a "supergene", a cluster of tightly linked genes [1-2]. The bird in question, the ruff (Philomachus pugnax), has a rather unusual reproductive system that consists of three distinct types of males ("reproductive morphs"): aggressive "independents" who represent the majority of males; a smaller fraction of non-territorial "satellites" who are submissive towards "independents"; and "faeders" who mimic females and are rare. Previous work has shown that the male morphs differ in major aspects of mating and aggression behavior, plumage coloration and body size, and that – intriguingly – this complex multi-trait polymorphism is apparently controlled by a single autosomal Mendelian locus with three alleles [3]. To uncover the genetic control of this polymorphism two independent teams, led by Terry Burke [1] and Leif Andersson [2], have set out to analyze the genomes of male ruffs. Using a combination of genomics and genetics, both groups managed to pin down the supergene locus and map it to a non-recombining, 4.5 Mb large inversion which arose 3.8 million years ago. While "independents" are homozygous for the ancestral uninverted sequence, "satellites" and "faeders" carry evolutionarily divergent, dominant alternative haplotypes of the inversion. Thus, as in several other notable cases, for example the supergene control of disassortative mating, aggressiveness and plumage color in white-throated sparrows [4], of mimicry in Heliconius and Papilio butterflies [5-6], or of social structure in ants [7], an inversion – behaving as a single "locus" – underpins the mechanistic basis of the supergene. More generally, and beyond inversions, a growing number of studies now shows that selection can favor the evolution of suppressed recombination, thereby leading to the emergence of clusters of tightly linked loci which can then control – presumably due to polygenic gene action – a suite of complex phenotypes [8-10]. A largely unresolved question in this field concerns the identity of the causative alleles and loci within a given supergene. Recent progress on this question has been made for example in Papilio polytes butterflies where a mimicry supergene has been found to involve – surprisingly – only a single but large gene: multiple mimicry alleles in the doublesex gene are maintained in strong linkage disequilibrium via an inversion. It will clearly be of great interest to see future examples of such a fine-scale genetic dissection of supergenes. In conclusion, we were impressed by the data and analyses of Küpper et al. [1] and Lamichhaney et al. [2]: both papers beautifully illustrate how genomics and evolutionary ecology can be combined to make new, exciting discoveries. Both papers will appeal to readers with an interest in supergenes, inversions, the interplay of selection and recombination, or the genetic control of complex phenotypes. References [1] Küpper C, Stocks M, Risse JE, dos Remedios N, Farrell LL, McRae SB, Morgan TC, Karlionova N, Pinchuk P, Verkuil YI, et al. 2016. A supergene determines highly divergent male reproductive morphs in the ruff. Nature Genetics 48:79-83. doi: 10.1038/ng.3443 [2] Lamichhaney S, Fan G, Widemo F, Gunnarsson U, Thalmann DS, Hoeppner MP, Kerje S, Gustafson U, Shi C, Zhang H, et al. 2016. Structural genomic changes underlie alternative reproductive strategies in the ruff (Philomachus pugnax). Nature Genetics 48:84-88. doi: 10.1038/ng.3430 [3] Lank DB, Smith CM, Hanotte O, Burke T, Cooke F. 1995. Genetic polymorphism for alternative mating behaviour in lekking male ruff Philomachus pugnax. Nature 378:59-62. doi: 10.1038/378059a0 [4] Tuttle Elaina M, Bergland Alan O, Korody Marisa L, Brewer Michael S, Newhouse Daniel J, Minx P, Stager M, Betuel A, Cheviron Zachary A, Warren Wesley C, et al. 2016. Divergence and Functional Degradation of a Sex Chromosome-like Supergene. Current Biology 26:344-350. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.069 [5] Joron M, Frezal L, Jones RT, Chamberlain NL, Lee SF, Haag CR, Whibley A, Becuwe M, Baxter SW, Ferguson L, et al. 2011. Chromosomal rearrangements maintain a polymorphic supergene controlling butterfly mimicry. Nature 477:203-206. doi: 10.1038/nature10341 [6] Kunte K, Zhang W, Tenger-Trolander A, Palmer DH, Martin A, Reed RD, Mullen SP, Kronforst MR. 2014. doublesex is a mimicry supergene. Nature 507:229-232. doi: 10.1038/nature13112 [7] Wang J, Wurm Y, Nipitwattanaphon M, Riba-Grognuz O, Huang Y-C, Shoemaker D, Keller L. 2013. A Y-like social chromosome causes alternative colony organization in fire ants. Nature 493:664-668. doi: 10.1038/nature11832 [8] Thompson MJ, Jiggins CD. 2014. Supergenes and their role in evolution. Heredity 113:1-8. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2014.20 [9] Schwander T, Libbrecht R, Keller L. 2014. Supergenes and Complex Phenotypes. Current Biology 24:R288-R294. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.056 [10] Charlesworth D. 2015. The status of supergenes in the 21st century: recombination suppression in Batesian mimicry and sex chromosomes and other complex adaptations. Evolutionary Applications 9:74-90. doi: 10.1111/eva.12291 | Structural genomic changes underlie alternative reproductive strategies in the ruff (Philomachus pugnax) | Lamichhaney S, Fan G, Widemo F, Gunnarsson U, Thalmann DS, Hoeppner MP, Kerje S, Gustafson U, Shi C, Zhang H, et al. | The ruff is a Palearctic wader with a spectacular lekking behavior where highly ornamented males compete for females1, 2, 3, 4. This bird has one of the most remarkable mating systems in the animal kingdom, comprising three different male morphs (... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Thomas Flatt | 2016-12-13 17:46:54 | View | |

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

A supergene determines highly divergent male reproductive morphs in the ruffKüpper C, Stocks M, Risse JE, dos Remedios N, Farrell LL, McRae SB, Morgan TC, Karlionova N, Pinchuk P, Verkuil YI, et al. doi:10.1038/ng.3443Supergene Control of a Reproductive PolymorphismRecommended by Thomas Flatt and Laurent KellerTwo back-to-back papers published earlier this year in Nature Genetics provide compelling evidence for the control of a male reproductive polymorphism in a wading bird by a "supergene", a cluster of tightly linked genes [1-2]. The bird in question, the ruff (Philomachus pugnax), has a rather unusual reproductive system that consists of three distinct types of males ("reproductive morphs"): aggressive "independents" who represent the majority of males; a smaller fraction of non-territorial "satellites" who are submissive towards "independents"; and "faeders" who mimic females and are rare. Previous work has shown that the male morphs differ in major aspects of mating and aggression behavior, plumage coloration and body size, and that – intriguingly – this complex multi-trait polymorphism is apparently controlled by a single autosomal Mendelian locus with three alleles [3]. To uncover the genetic control of this polymorphism two independent teams, led by Terry Burke [1] and Leif Andersson [2], have set out to analyze the genomes of male ruffs. Using a combination of genomics and genetics, both groups managed to pin down the supergene locus and map it to a non-recombining, 4.5 Mb large inversion which arose 3.8 million years ago. While "independents" are homozygous for the ancestral uninverted sequence, "satellites" and "faeders" carry evolutionarily divergent, dominant alternative haplotypes of the inversion. Thus, as in several other notable cases, for example the supergene control of disassortative mating, aggressiveness and plumage color in white-throated sparrows [4], of mimicry in Heliconius and Papilio butterflies [5-6], or of social structure in ants [7], an inversion – behaving as a single "locus" – underpins the mechanistic basis of the supergene. More generally, and beyond inversions, a growing number of studies now shows that selection can favor the evolution of suppressed recombination, thereby leading to the emergence of clusters of tightly linked loci which can then control – presumably due to polygenic gene action – a suite of complex phenotypes [8-10]. A largely unresolved question in this field concerns the identity of the causative alleles and loci within a given supergene. Recent progress on this question has been made for example in Papilio polytes butterflies where a mimicry supergene has been found to involve – surprisingly – only a single but large gene: multiple mimicry alleles in the doublesex gene are maintained in strong linkage disequilibrium via an inversion. It will clearly be of great interest to see future examples of such a fine-scale genetic dissection of supergenes. In conclusion, we were impressed by the data and analyses of Küpper et al. [1] and Lamichhaney et al. [2]: both papers beautifully illustrate how genomics and evolutionary ecology can be combined to make new, exciting discoveries. Both papers will appeal to readers with an interest in supergenes, inversions, the interplay of selection and recombination, or the genetic control of complex phenotypes. References [1] Küpper C, Stocks M, Risse JE, dos Remedios N, Farrell LL, McRae SB, Morgan TC, Karlionova N, Pinchuk P, Verkuil YI, et al. 2016. A supergene determines highly divergent male reproductive morphs in the ruff. Nature Genetics 48:79-83. doi: 10.1038/ng.3443 [2] Lamichhaney S, Fan G, Widemo F, Gunnarsson U, Thalmann DS, Hoeppner MP, Kerje S, Gustafson U, Shi C, Zhang H, et al. 2016. Structural genomic changes underlie alternative reproductive strategies in the ruff (Philomachus pugnax). Nature Genetics 48:84-88. doi: 10.1038/ng.3430 [3] Lank DB, Smith CM, Hanotte O, Burke T, Cooke F. 1995. Genetic polymorphism for alternative mating behaviour in lekking male ruff Philomachus pugnax. Nature 378:59-62. doi: 10.1038/378059a0 [4] Tuttle Elaina M, Bergland Alan O, Korody Marisa L, Brewer Michael S, Newhouse Daniel J, Minx P, Stager M, Betuel A, Cheviron Zachary A, Warren Wesley C, et al. 2016. Divergence and Functional Degradation of a Sex Chromosome-like Supergene. Current Biology 26:344-350. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.069 [5] Joron M, Frezal L, Jones RT, Chamberlain NL, Lee SF, Haag CR, Whibley A, Becuwe M, Baxter SW, Ferguson L, et al. 2011. Chromosomal rearrangements maintain a polymorphic supergene controlling butterfly mimicry. Nature 477:203-206. doi: 10.1038/nature10341 [6] Kunte K, Zhang W, Tenger-Trolander A, Palmer DH, Martin A, Reed RD, Mullen SP, Kronforst MR. 2014. doublesex is a mimicry supergene. Nature 507:229-232. doi: 10.1038/nature13112 [7] Wang J, Wurm Y, Nipitwattanaphon M, Riba-Grognuz O, Huang Y-C, Shoemaker D, Keller L. 2013. A Y-like social chromosome causes alternative colony organization in fire ants. Nature 493:664-668. doi: 10.1038/nature11832 [8] Thompson MJ, Jiggins CD. 2014. Supergenes and their role in evolution. Heredity 113:1-8. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2014.20 [9] Schwander T, Libbrecht R, Keller L. 2014. Supergenes and Complex Phenotypes. Current Biology 24:R288-R294. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.056 [10] Charlesworth D. 2015. The status of supergenes in the 21st century: recombination suppression in Batesian mimicry and sex chromosomes and other complex adaptations. Evolutionary Applications 9:74-90. doi: 10.1111/eva.12291 | A supergene determines highly divergent male reproductive morphs in the ruff | Küpper C, Stocks M, Risse JE, dos Remedios N, Farrell LL, McRae SB, Morgan TC, Karlionova N, Pinchuk P, Verkuil YI, et al. | Three strikingly different alternative male mating morphs (aggressive 'independents', semicooperative 'satellites' and female-mimic 'faeders') coexist as a balanced polymorphism in the ruff, *Philomachus pugnax*, a lek-breeding wading bird1, 2, 3.... |  | Adaptation, Genotype-Phenotype, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Thomas Flatt | 2016-12-13 17:28:13 | View | |

19 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Geographic body size variation in the periodical cicadas Magicicada: implications for life cycle divergence and local adaptationKoyama T, Ito H, Kakishima S, Yoshimura J, Cooley JR, Simon C, Sota T 10.1111/jeb.12653Megacicadas show a temperature-mediated converse Bergmann cline in body size (larger in the warmer south) but no body size difference between 13- and 17-year species pairsRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn and Thomas FlattPeriodical cicadas are a very prominent insect group in North America that are known for their large size, good looks, and loud sounds. However, they are probably known best to evolutionary ecologists because of their long juvenile periods of 13 or 17 years (prime numbers!), which they spend in the ground. Multiple related species living in the same area are often coordinated in emerging as adults during the same year, thereby presumably swamping any predators specialized on eating them. Reference [1] Koyama T, Ito H, Kakishima S, Yoshimura J, Cooley JR, Simon C, Sota T. 2015. Geographic body size variation in the periodical cicadas Magicicada: implications for life cycle divergence and local adaptation. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 28:1270-1277. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12653 | Geographic body size variation in the periodical cicadas Magicicada: implications for life cycle divergence and local adaptation | Koyama T, Ito H, Kakishima S, Yoshimura J, Cooley JR, Simon C, Sota T | Seven species in three species groups (Decim, Cassini and Decula) of periodical cicadas (*Magicicada*) occupy a wide latitudinal range in the eastern United States. To clarify how adult body size, a key trait affecting fitness, varies geographical... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Macroevolution, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Speciation | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2016-12-19 10:39:22 | View | |

04 Mar 2024

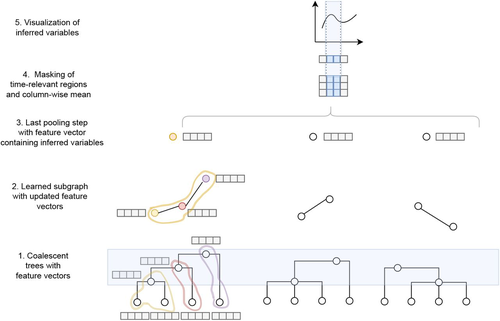

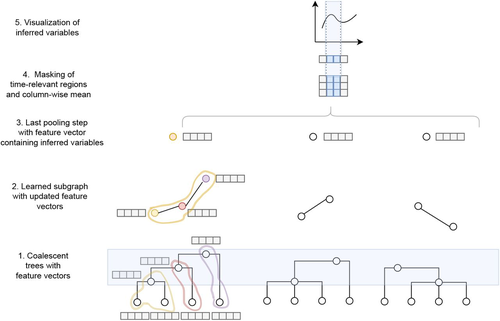

Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta CoalescentKevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.28.508873Beyond the standard coalescent: demographic inference with complete genomes and graph neural networks under the beta coalescentRecommended by Julien Yann Dutheil based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Modelling the evolution of complete genome sequences in populations requires accounting for the recombination process, as a single tree can no longer describe the underlying genealogy. The sequentially Markov coalescent (SMC, McVean and Cardin 2005; Marjoram and Wall 2006) approximates the standard coalescent with recombination process and permits estimating population genetic parameters (e.g., population sizes, recombination rates) using population genomic datasets. As such datasets become available for an increasing number of species, more fine-tuned models are needed to encompass the diversity of life cycles of organisms beyond the model species on which most methods have been benchmarked. The work by Korfmann et al. (Korfmann et al. 2024) represents a significant step forward as it accounts for multiple mergers in SMC models. Multiple merger models account for simultaneous coalescence events so that more than two lineages find a common ancestor in a given generation. This feature is not allowed in standard coalescent models and may result from selection or skewed offspring distributions, conditions likely met by a broad range of species, particularly microbial. Yet, this work goes beyond extending the SMC, as it introduces several methodological innovations. The "classical" SMC-based inference approaches rely on hidden Markov models to compute the likelihood of the data while efficiently integrating over the possible ancestral recombination graphs (ARG). Following other recent works (e.g. Gattepaille et al. 2016), Korfmann et al. propose to separate the ARG inference from model parameter estimation under maximum likelihood (ML). They introduce a procedure where the ARG is first reconstructed from the data and then taken as input in the model fitting step. While this approach does not permit accounting for the uncertainty in the ARG reconstruction (which is typically large), it potentially allows for the extraction of more information from the ARG, such as the occurrence of multiple merging events. Going away from maximum likelihood inference, the authors trained a graph neural network (GNN) on simulated ARGs, introducing a new, flexible way to estimate population genomic parameters. The authors used simulations under a beta-coalescent model with diverse demographic scenarios and showed that the ML and GNN approaches introduced can reliably recover the simulated parameter values. They further show that when the true ARG is given as input, the GNN outperforms the ML approach, demonstrating its promising power as ARG reconstruction methods improve. In particular, they showed that trained GNNs can disentangle the effects of selective sweeps and skewed offspring distributions while inferring past population size changes. This work paves the way for new, exciting applications, though many questions must be answered. How frequent are multiple mergers? As the authors showed that these events "erase" the record of past demographic events, how many genomes are needed to conduct reliable inference, and can the methods computationally cope with the resulting (potentially large) amounts of required data? This is particularly intriguing as micro-organisms, prone to strong selection and skewed offspring distributions, also tend to carry smaller genomes. References Gattepaille L, Günther T, Jakobsson M. 2016. Inferring Past Effective Population Size from Distributions of Coalescent Times. Genetics 204:1191-1206. | Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta Coalescent | Kevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier | <p style="text-align: justify;">The reproductive mechanism of a species is a key driver of genome evolution. The standard Wright-Fisher model for the reproduction of individuals in a population assumes that each individual produces a number of off... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Theory, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics | Julien Yann Dutheil | 2023-07-31 13:11:22 | View | |

22 May 2023

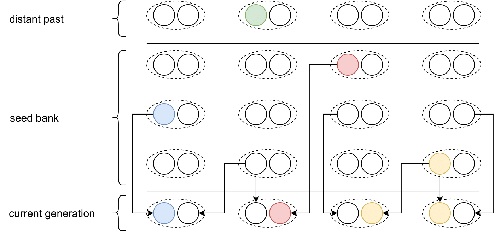

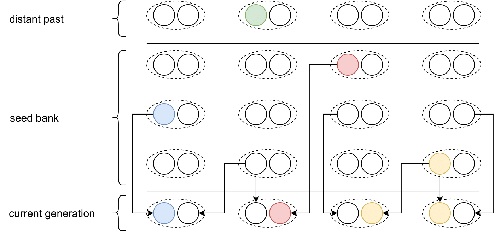

Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweepsKevin Korfmann, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.26.489499New insights into the dynamics of selective sweeps in seed-banked speciesRecommended by Renaud Vitalis based on reviews by Guillaume Achaz, Jere Koskela, William Shoemaker and Simon Boitard based on reviews by Guillaume Achaz, Jere Koskela, William Shoemaker and Simon Boitard

Many organisms across the Tree of life have the ability to produce seeds, eggs, cysts, or spores, that can remain dormant for several generations before hatching. This widespread adaptive trait in bacteria, fungi, plants and animals, has a significant impact on the ecology, population dynamics and population genetics of species that express it (Evans and Dennehy 2005). In population genetics, and despite the recognition of its evolutionary importance in many empirical studies, few theoretical models have been developed to characterize the evolutionary consequences of this trait on the level and distribution of neutral genetic diversity (see, e.g., Kaj et al. 2001; Vitalis et al. 2004), and also on the dynamics of selected alleles (see, e.g., Živković and Tellier 2018). However, due to the complexity of the interactions between evolutionary forces in the presence of dormancy, the fate of selected mutations in their genomic environment is not yet fully understood, even from the most recently developed models. In a comprehensive article, Korfmann et al. (2023) aim to fill this gap by investigating the effect of germ banking on the probability of (and time to) fixation of beneficial mutations, as well as on the shape of the selective sweep in their vicinity. To this end, Korfmann et al. (2023) developed and released their own forward-in-time simulator of genome-wide data, including neutral and selected polymorphisms, that makes use of Kelleher et al.’s (2018) tree sequence toolkit to keep track of gene genealogies. The originality of Korfmann et al.’s (2023) study is to provide new quantitative results for the effect of dormancy on the time to fixation of positively selected mutations, the shape of the genomic landscape in the vicinity of these mutations, and the temporal dynamics of selective sweeps. Their major finding is the prediction that germ banking creates narrower signatures of sweeps around positively selected sites, which are detectable for increased periods of time (as compared to a standard Wright-Fisher population). The availability of Korfmann et al.’s (2023) code will allow a wider range of parameter values to be explored, to extend their results to the particularities of the biology of many species. However, as they chose to extend the haploid coalescent model of Kaj et al. (2001), further development is needed to confirm the robustness of their results with a more realistic diploid model of seed dormancy. REFERENCES Evans, M. E. K., and J. J. Dennehy (2005) Germ banking: bet-hedging and variable release from egg and seed dormancy. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 80(4): 431-451. https://doi.org/10.1086/498282 Kaj, I., S. Krone, and M. Lascoux (2001) Coalescent theory for seed bank models. Journal of Applied Probability, 38(2): 285-300. https://doi.org/10.1239/jap/996986745 Kelleher, J., K. R. Thornton, J. Ashander, and P. L. Ralph (2018) Efficient pedigree recording for fast population genetics simulation. PLoS Computational Biology, 14(11): e1006581. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006581 Korfmann, K., D. Abu Awad, and A. Tellier (2023) Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweeps. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.26.489499 Vitalis, R., S. Glémin, and I. Olivieri (2004) When genes go to sleep: the population genetic consequences of seed dormancy and monocarpic perenniality. American Naturalist, 163(2): 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1086/381041 Živković, D., and A. Tellier (2018). All but sleeping? Consequences of soil seed banks on neutral and selective diversity in plant species. Mathematical Modelling in Plant Biology, 195-212. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99070-5_10 | Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweeps | Kevin Korfmann, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Seed banking (or dormancy) is a widespread bet-hedging strategy, generating a form of population overlap, which decreases the magnitude of genetic drift. The methodological complexity of integrating this trait impli... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics | Renaud Vitalis | 2022-05-23 13:01:57 | View | |

18 May 2018

Modularity of genes involved in local adaptation to climate despite physical linkageKatie E. Lotterhos, Sam Yeaman, Jon Degner, Sally Aitken, Kathryn Hodgins https://doi.org/10.1101/202481Differential effect of genes in diverse environments, their role in local adaptation and the interference between genes that are physically linkedRecommended by Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins based on reviews by Tanja Pyhäjärvi and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tanja Pyhäjärvi and 1 anonymous reviewer

The genome of eukaryotic species is a complex structure that experience many different interactions within itself and with the surrounding environment. The genetic architecture of a phenotype (that is, the set of genetic elements affecting a trait of the organism) plays a fundamental role in understanding the adaptation process of a species to, for example, different climate environments, or to its interaction with other species. Thus, it is fundamental to study the different aspects of the genetic architecture of the species and its relationship with its surronding environment. Aspects such as modularity (the number of genetic units and the degree to which each unit is affecting a trait of the organism), pleiotropy (the number of different effects that a genetic unit can have on an organism) or linkage (the degree of association between the different genetic units) are essential to understand the genetic architecture and to interpret the effects of selection on the genome. Indeed, the knowledge of the different aspects of the genetic architecture could clarify whether genes are affected by multiple aspects of the environment or, on the contrary, are affected by only specific aspects [1,2]. The work performed by Lotterhos et al. [3] sought to understand the genetic architecture of the adaptation to different environments in lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), considering as candidate SNPs those previously detected as a result of its extreme association patterns to different environmental variables or to extreme population differentiation. This consideration is very important because the study is only relevant if the studied markers are under the effect of selection. Otherwise, the genetic architecture of the adaptation to different environments would be masked by other (neutral) kind of associations that would be difficult to interpret [4,5]. In order to understand the relationship between genetic architecture and adaptation, it is relevant to detect the association networks of the candidate SNPs with climate variables (a way to measure modularity) and if these SNPs (and loci) are affected by single or multiple environments (a way to measure pleiotropy). The authors used co-association networks, an innovative approach in this field, to analyse the interaction between the environmental information and the genetic polymorphism of each individual. This methodology is more appropriate than other multivariate methods - such as analysis based on principal components - because it is possible to cluster SNPs based on associations with similar environmental variables. In this sense, the co-association networks allowed to both study the genetic and physical linkage between different co-associations modules but also to compare two different models of evolution: a Modular environmental response architecture (specific genes are affected by specific aspects of the environment) or a Universal pleiotropic environmental response architecture (all genes are affected by all aspects of the environment). The representation of different correlations between allelic frequency and environmental factors (named galaxy biplots) are especially informative to understand the effect of the different clusters on specific aspects of the environment (for example, the co-association network ‘Aridity’ shows strong associations with hot/wet versus cold/dry environments). The analysis performed by Lotterhos et al. [3], although it has some unavoidable limitations (e.g., only extreme candidate SNPs are selected, limiting the results to the stronger effects; the genetic and physical map is incomplete in this species), includes relevant results and also implements new methodologies in the field. To highlight some of them: the preponderance of a Modular environmental response architecture (evolution in separated modules), the detection of physical linkage among SNPs that are co-associated with different aspects of the environment (which was unexpected a priori), the implementation of co-association networks and galaxy biplots to see the effect of modularity and pleiotropy on different aspects of environment. Finally, this work contains remarkable introductory Figures and Tables explaining unambiguously the main concepts [6] included in this study. This work can be treated as a starting point for many other future studies in the field. References [1] Hancock AM, Brachi B, Faure N, Horton MW, Jarymowycz LB, Sperone FG, Toomajian C, Roux F & Bergelson J. 2011. Adaptation to climate across the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Science 334: 83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1209244 | Modularity of genes involved in local adaptation to climate despite physical linkage | Katie E. Lotterhos, Sam Yeaman, Jon Degner, Sally Aitken, Kathryn Hodgins | <p>Background: Physical linkage among genes shaped by different sources of selection is a fundamental aspect of genetic architecture. Theory predicts that evolution in complex environments selects for modular genetic architectures and high recombi... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution | Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins | 2017-10-15 19:21:57 | View | |

02 Feb 2023

Heterogeneities in infection outcomes across species: sex and tissue differences in virus susceptibilityKatherine E Roberts, Ben Longdon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.01.514663Susceptibility to infection is not explained by sex or differences in tissue tropism across different species of DrosophilaRecommended by Alison Duncan based on reviews by Greg Hurst and 1 anonymous reviewerUnderstanding factors explaining both intra and interspecific variation in susceptibility to infection by parasites remains a key question in evolutionary biology. Within a species variation in susceptibility is often explained by differences in behaviour affecting exposure to infection and/or resistance affecting the degree by which parasite growth is controlled (Roy & Kirchner, 2000, Behringer et al., 2000). This can vary between the sexes (Kelly et al., 2018) and may be explained by the ability of a parasite to attack different organs or tissues (Brierley et al., 2019). However, what goes on within one species is not always relevant to another, making it unclear when patterns can be scaled up and generalised across species. This is also important to understand when parasites may jump hosts, or identify species that may be susceptible to a host jump (Longdon et al., 2015). Phylogenetic distance between hosts is often an important factor explaining susceptibility to a particular parasite in plant and animal hosts (Gilbert & Webb, 2007, Faria et al., 2013). In two separate experiments, Roberts and Longdon (Roberts & Longdon, 2022) investigated how sex and tissue tropism affected variation in the load of Drosophila C Virus (DCV) across multiple Drosophila species. DCV load has been shown to correlate positively with mortality (Longdon et al., 2015). Overall, they found that load did not vary between the sexes; within a species males and females had similar DCV loads for 31 different species. There was some variation in levels of DCV growth in different tissue types, but these too were consistent across males for 7 species of Drosophila. Instead, in both experiments, host phylogeny or interspecific variation, explained differences in DCV load with some species being more infected than others. This study is neat in that it incorporates and explores simultaneously both intra and interspecific variation in infection-related life-history traits which is not often done (but see (Longdon et al., 2015, Imrie et al., 2021, Longdon et al., 2011, Johnson et al., 2012). Indeed, most studies to date explore either inter-specific differences in susceptibility to a parasite (it can or can’t infect a given species) (Davies & Pedersen, 2008, Pfenning-Butterworth et al., 2021) or intra-specific variability in infection-related traits (infectivity, resistance etc.) due to factors such as sex, genotype and environment (Vale et al., 2008, Lambrechts et al., 2006). This work thus advances on previous studies, while at the same time showing that sex differences in parasite load are not necessarily pervasive. References Behringer DC, Butler MJ, Shields JD (2006) Avoidance of disease by social lobsters. Nature, 441, 421–421. https://doi.org/10.1038/441421a Brierley L, Pedersen AB, Woolhouse MEJ (2019) Tissue tropism and transmission ecology predict virulence of human RNA viruses. PLOS Biology, 17, e3000206. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000206 Davies TJ, Pedersen AB (2008) Phylogeny and geography predict pathogen community similarity in wild primates and humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275, 1695–1701. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2008.0284 Faria NR, Suchard MA, Rambaut A, Streicker DG, Lemey P (2013) Simultaneously reconstructing viral cross-species transmission history and identifying the underlying constraints. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368, 20120196. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0196 Gilbert GS, Webb CO (2007) Phylogenetic signal in plant pathogen–host range. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 4979–4983. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0607968104 Imrie RM, Roberts KE, Longdon B (2021) Between virus correlations in the outcome of infection across host species: Evidence of virus by host species interactions. Evolution Letters, 5, 472–483. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.247 Johnson PTJ, Rohr JR, Hoverman JT, Kellermanns E, Bowerman J, Lunde KB (2012) Living fast and dying of infection: host life history drives interspecific variation in infection and disease risk. Ecology Letters, 15, 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01730.x Kelly CD, Stoehr AM, Nunn C, Smyth KN, Prokop ZM (2018) Sexual dimorphism in immunity across animals: a meta-analysis. Ecology Letters, 21, 1885–1894. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13164 Lambrechts L, Chavatte J-M, Snounou G, Koella JC (2006) Environmental influence on the genetic basis of mosquito resistance to malaria parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 1501–1506. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3483 Longdon B, Hadfield JD, Day JP, Smith SCL, McGonigle JE, Cogni R, Cao C, Jiggins FM (2015) The Causes and Consequences of Changes in Virulence following Pathogen Host Shifts. PLOS Pathogens, 11, e1004728. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004728 Longdon B, Hadfield JD, Webster CL, Obbard DJ, Jiggins FM (2011) Host Phylogeny Determines Viral Persistence and Replication in Novel Hosts. PLOS Pathogens, 7, e1002260. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002260 Pfenning-Butterworth AC, Davies TJ, Cressler CE (2021) Identifying co-phylogenetic hotspots for zoonotic disease. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 376, 20200363. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0363 Roberts KE, Longdon B (2023) Heterogeneities in infection outcomes across species: examining sex and tissue differences in virus susceptibility. bioRxiv 2022.11.01.514663, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.01.514663 Roy BA, Kirchner JW (2000) Evolutionary Dynamics of Pathogen Resistance and Tolerance. Evolution, 54, 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00007.x Vale PF, Stjernman M, Little TJ (2008) Temperature-dependent costs of parasitism and maintenance of polymorphism under genotype-by-environment interactions. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 21, 1418–1427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01555.x | Heterogeneities in infection outcomes across species: sex and tissue differences in virus susceptibility | Katherine E Roberts, Ben Longdon | <p style="text-align: justify;">Species vary in their susceptibility to pathogens, and this can alter the ability of a pathogen to infect a novel host. However, many factors can generate heterogeneity in infection outcomes, obscuring our ability t... | Evolutionary Ecology | Alison Duncan | Anonymous, Greg Hurst | 2022-11-03 11:17:42 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer