Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▼ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

28 Feb 2018

Insects and incest: sib-mating tolerance in natural populations of a parasitoid waspMarie Collet, Isabelle Amat, Sandrine Sauzet, Alexandra Auguste, Xavier Fauvergue, Laurence Mouton, Emmanuel Desouhant https://doi.org/10.1101/169268Incestuous insects in nature despite occasional fitness costsRecommended by Caroline Nieberding and Bertanne Visser based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersInbreeding, or mating between relatives, generally lowers fitness [1]. Mating between genetically similar individuals can result in higher levels of homozygosity and consequently a higher frequency with which recessive disease alleles may be expressed within a population. Reduced fitness as a consequence of inbreeding, or inbreeding depression, can vary between individuals, sexes, populations and species [2], but remains a pervasive challenge for many organisms with small local population sizes, including humans [3]. But all is not lost for individuals within small populations, because an array of mechanisms can be employed to evade the negative effects of inbreeding [4], including sib-mating avoidance and dispersal [5, 6]. Despite thorough investigation of inbreeding and sib-mating avoidance in the laboratory, only very few studies have ventured into the field besides studies on vertebrates and eusocial insects. The study of Collet et al. [7] is a surprising exception, where the effect of male density and frequency of relatives on inbreeding avoidance was tested in the laboratory, after which robust field collections and microsatellite genotyping were used to infer relatedness and dispersal in natural populations. The parasitic wasp Venturia canescens is an excellent model system to study inbreeding, because mating success was previously found to decrease with increasing relatedness between mates in the laboratory [8] and this species thus suffers from inbreeding depression [9–11]. The authors used an elegant design combining population genetics and model simulations to estimate relatedness of mating partners in the field and compared that with a theoretical distribution of potential mate encounters when random mating is assumed. One of the most important findings of this study is that mating between siblings is not avoided in this species in the wild, despite negative fitness effects when inbreeding does occur. Similar findings were obtained for another insect species, the field cricket Gryllus campestris [12], which leaves us to wonder whether inbreeding tolerance could be more common in nature than currently appreciated. The authors further looked into sex-specific dispersal patterns between two patches located a few hundred meters apart. Females were indeed shown to be more related within a patch, but no genetic differences were observed between males, suggesting that V. canescens males more readily disperse. Moreover, microsatellite data at 18 different loci did not reveal genetic differentiation between populations approximately 300 kilometers apart. Gene flow is thus occurring over considerable distances, which could play an important role in the ability of this species to avoid negative fitness consequences of inbreeding in nature. Another interesting aspect of this work is that discrepancies were found between laboratory- and field-based data. What is the relevance of laboratory-based experiments if they cannot predict what is happening in the wild? Many, if not most, biologists (including us) bring our model system into the laboratory to control, at least to some extent, the plethora of environmental factors that could potentially affect our system (in ways that we do not want). Most behavioral studies on mating patterns and sexual selection are conducted in standardized laboratory conditions, but sexual selection is in essence social selection, because an individual’s fitness is partly determined by the phenotype of its social partners (i.e. the social environment) [13]. The social environment may actually dictate the expression of female mate choice and it is unclear how potential laboratory-induced social biases affect mating outcome. In V. canescens, findings using field-caught individuals paint a completely opposite picture of what was previously shown in the laboratory, i.e. sib-avoidance is not taking place in the field. It is likely that density, level of relatedness, sex ratio in the field, and/or the size of experimental arenas in the lab are all factors affecting mate selectivity, as we have previously shown in a butterfly [14–16]. If females, for example, typically only encounter a few males in sequence in the wild, it may be problematic for them to express choosiness when confronted simultaneously with two or more males in the laboratory. A recent study showed that, in the wild, female moths take advantage of staying in groups to blur male choosiness [17]. It is becoming more and more clear that what we observe in the laboratory may not actually reflect what is happening in nature [18]. Instead of ignoring the species-specific life history and ecological features of our favorite species when conducting lab experiments, we suggest that it is time to accept that we now have the theoretical foundations to tease apart what in this “environmental noise” actually shapes sexual selection in nature. Explicitly including ecology in studies on sexual selection will allow us to make more meaningful conclusions, i.e. rather than “this is what may happen in the wild”, we would be able to state “this is what often happens in nature”. References [1] Charlesworth D & Willis JH. 2009. The genetics of inbreeding depression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10: 783–796. doi: 10.1038/nrg2664 | Insects and incest: sib-mating tolerance in natural populations of a parasitoid wasp | Marie Collet, Isabelle Amat, Sandrine Sauzet, Alexandra Auguste, Xavier Fauvergue, Laurence Mouton, Emmanuel Desouhant | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (http://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100047) 1. Sib-mating avoidance is a pervasive behaviour that likely evolves in species subject to inbreeding dep... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Sexual Selection | Caroline Nieberding | 2017-07-28 09:23:20 | View | |

05 Dec 2017

Reconstruction of body mass evolution in the Cetartiodactyla and mammals using phylogenomic dataEmeric Figuet, Marion Ballenghien, Nicolas Lartillot, Nicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/139147Predicting small ancestors using contemporary genomes of large mammalsRecommended by Bruce Rannala based on reviews by Bruce Rannala and 1 anonymous reviewerRecent methodological developments and increased genome sequencing efforts have introduced the tantalizing possibility of inferring ancestral phenotypes using DNA from contemporary species. One intriguing application of this idea is to exploit the apparent correlation between substitution rates and body size to infer ancestral species' body sizes using the inferred patterns of substitution rate variation among species lineages based on genomes of extant species [1]. References [1] Romiguier J, Ranwez V, Douzery EJP and Galtier N. 2013. Genomic evidence for large, long-lived ancestors to placental mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 5–13. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss211 [2] Figuet E, Ballenghien M, Lartillot N and Galtier N. 2017. Reconstruction of body mass evolution in the Cetartiodactyla and mammals using phylogenomic data. bioRxiv, ver. 3 of 4th December 2017. 139147. doi: 10.1101/139147 | Reconstruction of body mass evolution in the Cetartiodactyla and mammals using phylogenomic data | Emeric Figuet, Marion Ballenghien, Nicolas Lartillot, Nicolas Galtier | <p>Reconstructing ancestral characters on a phylogeny is an arduous task because the observed states at the tips of the tree correspond to a single realization of the underlying evolutionary process. Recently, it was proposed that ancestral traits... |  | Genome Evolution, Life History, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Bruce Rannala | 2017-05-18 15:28:58 | View | |

28 Mar 2024

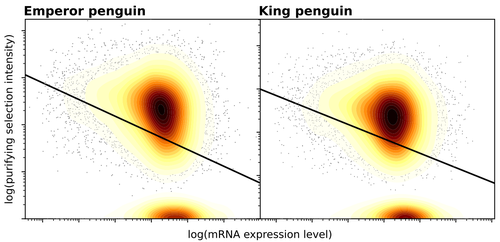

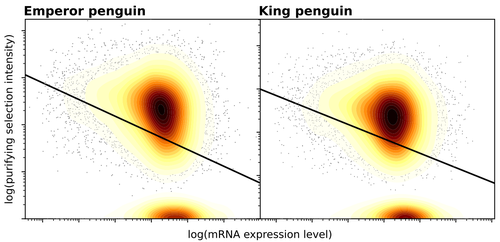

Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populationsEmiliano Trucchi, Piergiorgio Massa, Francesco Giannelli, Thibault Latrille, Flavia A.N. Fernandes, Lorena Ancona, Nils Chr Stenseth, Joan Ferrer Obiol, Josephine Paris, Giorgio Bertorelle, Celine Le Bohec https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552445Purifying selection on highly expressed genes in PenguinsRecommended by Bruce Rannala based on reviews by Tanja Pyhäjärvi and 1 anonymous reviewerGiven the general importance of protein expression levels, in cells it is widely accepted that gene expression levels are often a target of natural selection and that most mutations affecting gene expression levels are therefore likely to be deleterious [1]. However, it is perhaps less obvious that the strength of selection on the regulated genes themselves may be influenced by their expression levels. This might be due to harmful effects of misfolded proteins, for example, when higher protein concentrations exist in cells [2]. Recent studies have suggested that highly expressed genes accumulate fewer deleterious mutations; thus a positive relationship appears to exist between gene expression levels and the relative strength of purifying selection [3]. The recommended paper by Trucchi et al. [4] examines the relationship between gene expression, purifying selection and a third variable -- effective population size -- in populations of two species of penguin with different population sizes, the Emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) and the King penguin (A. patagonicus). Using transcriptomic data and computer simulations modeling selection, they examine patterns of nonsynonymous and synonymous segregating polymorphisms (p) across genes in the two populations, concluding that even in relatively small populations purifying selection has an important effect in eliminating deleterious mutations. References 1] Gilad Y, Oshlack A, and Rifkin SA. 2006. Natural selection on gene expression. Trends in Genetics 22: 456-461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.002 [4] Trucchi E, Massa P, Giannelli F, Latrille T, Fernandes FAN, Ancona L, Stenseth NC, Obiol JF, Paris J, Bertorelle G, and Le Bohec, C. 2023. Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populations. bioRxiv 2023.08.08.552445, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552445

| Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populations | Emiliano Trucchi, Piergiorgio Massa, Francesco Giannelli, Thibault Latrille, Flavia A.N. Fernandes, Lorena Ancona, Nils Chr Stenseth, Joan Ferrer Obiol, Josephine Paris, Giorgio Bertorelle, Celine Le Bohec | <p style="text-align: justify;">Purifying selection is the most pervasive type of selection, as it constantly removes deleterious mutations arising in populations, directly scaling with population size. Highly expressed genes appear to accumulate ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Bruce Rannala | 2023-08-09 17:53:03 | View | |

18 Aug 2020

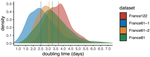

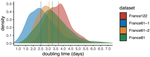

Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemics in FranceGonché Danesh, Baptiste Elie,Yannis Michalakis, Mircea T. Sofonea, Antonin Bal, Sylvie Behillil, Grégory Destras, David Boutolleau, Sonia Burrel, Anne-Geneviève Marcelin, Jean-Christophe Plantier, Vincent Thibault, Etienne Simon-Loriere, Sylvie van der Werf, Bruno Lina, Laurence Josset, Vincent Enouf, Samuel Alizon and the COVID SMIT PSL group https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.03.20119925SARS-Cov-2 genome sequence analysis suggests rapid spread followed by epidemic slowdown in FranceRecommended by B. Jesse Shapiro based on reviews by Luca Ferretti and 2 anonymous reviewersSequencing and analyzing SARS-Cov-2 genomes in nearly real time has the potential to quickly confirm (and inform) our knowledge of, and response to, the current pandemic [1,2]. In this manuscript [3], Danesh and colleagues use the earliest set of available SARS-Cov-2 genome sequences available from France to make inferences about the timing of the major epidemic wave, the duration of infections, and the efficacy of lockdown measures. Their phylodynamic estimates -- based on fitting genomic data to molecular clock and transmission models -- are reassuringly close to estimates based on 'traditional' epidemiological methods: the French epidemic likely began in mid-January or early February 2020, and spread relatively rapidly (doubling every 3-5 days), with people remaining infectious for a median of 5 days [4,5]. These transmission parameters are broadly in line with estimates from China [6,7], but are currently unknown in France (in the absence of contact tracing data). By estimating the temporal reproductive number (Rt), the authors detected a slowing down of the epidemic in the most recent period of the study, after mid-March, supporting the efficacy of lockdown measures. References [1] Grubaugh, N. D., Ladner, J. T., Lemey, P., Pybus, O. G., Rambaut, A., Holmes, E. C., & Andersen, K. G. (2019). Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty-first century. Nature microbiology, 4(1), 10-19. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0296-2 | Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemics in France | Gonché Danesh, Baptiste Elie,Yannis Michalakis, Mircea T. Sofonea, Antonin Bal, Sylvie Behillil, Grégory Destras, David Boutolleau, Sonia Burrel, Anne-Geneviève Marcelin, Jean-Christophe Plantier, Vincent Thibault, Etienne Simon-Loriere, Sylvie va... | <p>France was one of the first countries to be reached by the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, we analyse 196 SARS-Cov-2 genomes collected between Jan 24 and Mar 24 2020, and perform a phylodynamics analysis. In particular, we analyse the doubling time, r... |  | Evolutionary Epidemiology, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | B. Jesse Shapiro | 2020-06-04 13:13:57 | View | |

30 Jun 2023

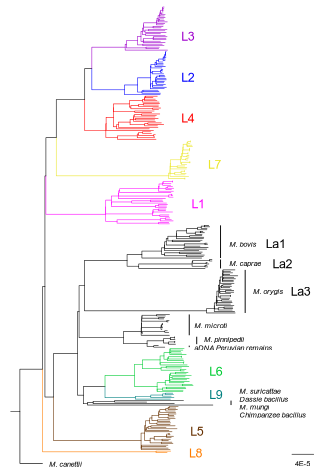

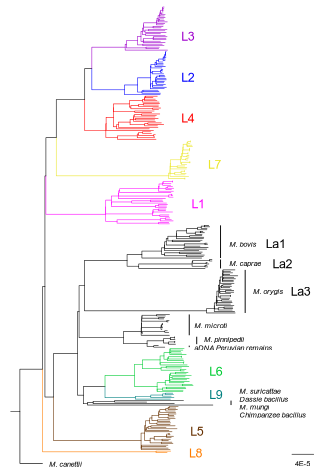

How do monomorphic bacteria evolve? The Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and the awkward population genetics of extreme clonalityChristoph Stritt, Sebastien Gagneux https://doi.org/10.32942/X2GW2PHow the tubercle bacillus got its genome: modernising, modelling, and making sense of the stories we tellRecommended by B. Jesse Shapiro based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersIn this instructive review, Stritt and Gagneux offer a balanced perspective on the evolutionary forces shaping Mycobacterium tuberculosis and make the case that our instinct for storytelling be balanced with quantitative models. M. tuberculosis is perhaps the best-known clonal bacterial pathogen – evolving largely in the absence of horizontal gene transfer. Its genome is full of puzzling patterns, including much higher GC content than most intracellular pathogens (which suggests efficient selection to resist AT-skewed mutational bias) but a very high ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rates (dN/dS ~ 0.5, typically interpreted as weak selection against deleterious amino acid changes). The authors offer alternative explanations for these patterns, framing the question: is M. tuberculosis evolution shaped mainly by drift or by efficient selection? They propose that this question can only be answered by accounting for the pathogen’s extreme clonality. A clonal lifestyle can have its advantages, for example when adaptations must arise in a particular order (Kondrashov and Kondrashov 2001). An important disadvantage highlighted by the authors are linkage effects: without recombination to shuffle them up, beneficial mutations are linked to deleterious mutations in the same genome (hitchhiking) and purging deleterious mutations also purges neutral diversity across the genome (background selection). The authors propose the latter – efficient purifying selection and strong linkage – as an explanation for the low genetic diversity observed in M. tuberculosis. This is of course not exclusive of other related explanations, such as clonal interference (Gerrish and Lenski 1998). They also champion the use of forward evolutionary simulations (Haller and Messer 2019) to model the interplay between selection, recombination, and demography as a powerful alternative to traditional backward coalescent models. At times, Stritt and Gagneux are pessimistic about our existing methods – arguing that dN/dS and homoplasies “tell us little about the frequency and strength of selection.” Even though I favour a more optimistic view, I fully agree that our traditional population genetic metrics are sensitive to a slew of different deviations from a standard neutral evolution model and must be interpreted with caution. As I and others have argued, the extent of recombination (measured as the amount of linkage in a genome) is a key factor in determining how best to test for natural selection (Shapiro et al. 2009) and to conduct genotype-phenotype association studies (Chen and Shapiro 2021) in microbes. While this article is focused on the well-studied M. tuberculosis complex, there are many parallels with other clonal bacteria, including pathogens and symbionts. Whatever your favourite bug, we must all be careful to make sure the stories we tell about them are not “just so tales” but are supported, to the extent possible, by data and quantitative models. References Chen, Peter E., and B. Jesse Shapiro. 2021. "Classic Genome-Wide Association Methods Are Unlikely to Identify Causal Variants in Strongly Clonal Microbial Populations." bioRxiv. Stritt, C., Gagneux, S. (2023). How do monomorphic bacteria evolve? The Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and the awkward population genetics of extreme clonality. EcoEvoRxiv, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2GW2P | How do monomorphic bacteria evolve? The *Mycobacterium tuberculosis* complex and the awkward population genetics of extreme clonality | Christoph Stritt, Sebastien Gagneux | <p style="text-align: justify;">Exchange of genetic material through sexual reproduction or horizontal gene transfer is ubiquitous in nature. Among the few outliers that rarely recombine and mainly evolve by <em>de novo</em> mutation are a group o... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | B. Jesse Shapiro | Gonçalo Themudo | 2022-12-16 13:41:53 | View |

05 Feb 2021

Relaxation of purifying selection suggests low effective population size in eusocial Hymenoptera and solitary pollinating beesArthur Weyna, Jonathan Romiguier https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.14.038893Multi-gene and lineage comparative assessment of the strength of selection in HymenopteraRecommended by Bertanne Visser based on reviews by Michael Lattorff and 1 anonymous reviewerGenetic variation is the raw material for selection to act upon and the amount of genetic variation present within a population is a pivotal determinant of a population’s evolutionary potential. A large effective population size, i.e., the ideal number of individuals experiencing the same amount of genetic drift and inbreeding as an actual population, Ne (Wright 1931, Crow 1954), thus increases the probability of long-term survival of a population. However, natural populations, as opposed to theoretical ones, rarely adhere to the requirements of an ideal panmictic population (Sjödin et al. 2005). A range of circumstances can reduce Ne, including the structuring of populations (through space and time, as well as age and developmental stages) and inbreeding (Charlesworth 2009). In mammals, species with a larger body mass (as a proxy for lower Ne) were found to have a higher rate of nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions (that alter the amino acid sequence of a protein), as well as radical amino acid substitutions (altering the physicochemical properties of a protein) (Popadin et al. 2007). In general, low effective population sizes increase the chance of mutation accumulation and drift, while reducing the strength of selection (Sjödin et al. 2005). References Charlesworth, B. (2009). Effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation. Nature Reviews Genetics, 10(3), 195-205. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2526 | Relaxation of purifying selection suggests low effective population size in eusocial Hymenoptera and solitary pollinating bees | Arthur Weyna, Jonathan Romiguier | <p>With one of the highest number of parasitic, eusocial and pollinator species among all insect orders, Hymenoptera features a great diversity of lifestyles. At the population genetic level, such life-history strategies are expected to decrease e... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Genome Evolution, Life History, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Bertanne Visser | 2020-04-21 17:30:57 | View | |

22 Oct 2019

Geographic variation in adult and embryonic desiccation tolerance in a terrestrial-breeding frogRudin-Bitterli, T, Evans, J. P. and Mitchell, N. J. https://doi.org/10.1101/314351Tough as old boots: amphibians from drier habitats are more resistant to desiccation, but less flexible at exploiting wet conditionsRecommended by Ben Phillips based on reviews by Juan Diego Gaitan-Espitia, Jennifer Nicole Lohr and 1 anonymous reviewerSpecies everywhere are facing rapid climatic change, and we are increasingly asking whether populations will adapt, shift, or perish [1]. There is a growing realisation that, despite limited within-population genetic variation, many species exhibit substantial geographic variation in climate-relevant traits. This geographic variation might play an important role in facilitating adaptation to climate change [2,3]. References [1] Hoffmann, A. A., and Sgrò, C. M. (2011). Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature, 470(7335), 479–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09670 | Geographic variation in adult and embryonic desiccation tolerance in a terrestrial-breeding frog | Rudin-Bitterli, T, Evans, J. P. and Mitchell, N. J. | <p>Intra-specific variation in the ability of individuals to tolerate environmental perturbations is often neglected when considering the impacts of climate change. Yet this information is potentially crucial for mitigating any deleterious effects... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology | Ben Phillips | 2018-05-07 03:35:08 | View | |

16 Dec 2020

Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivityMaxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Marjorie Haond, Aurélie Blin, Eric Lombaert, Vincent Calcagno, Simon Fellous, Ludovic Mailleret, Thibaut Malausa, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.13.092775The push and pull between theory and data in understanding the dynamics of invasionRecommended by Ben Phillips based on reviews by Laura Naslund and 2 anonymous reviewersExciting times are afoot for those of us interested in the ecology and evolution of invasive populations. Recent years have seen evolutionary process woven firmly into our understanding of invasions (Miller et al. 2020). This integration has inspired a welter of empirical and theoretical work. We have moved from field observations and verbal models to replicate experiments and sophisticated mathematical models. Progress has been rapid, and we have seen science at its best; an intimate discussion between theory and data. References Bîrzu, G., Matin, S., Hallatschek, O., and Korolev, K. S. (2019). Genetic drift in range expansions is very sensitive to density dependence in dispersal and growth. Ecology Letters, 22(11), 1817-1827. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13364 | Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivity | Maxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Marjorie Haond, Aurélie Blin, Eric Lombaert, Vincent Calcagno, Simon Fellous, Ludovic Mailleret, Thibaut Malausa, Elodie Vercken | <p>Range expansions are key processes shaping the distribution of species; their ecological and evolutionary dynamics have become especially relevant today, as human influence reshapes ecosystems worldwide. Many attempts to explain and predict ran... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Ben Phillips | 2020-08-04 12:51:56 | View | |

01 Mar 2024

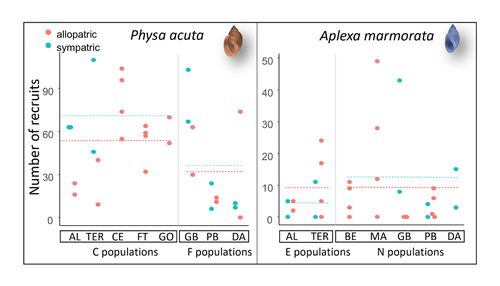

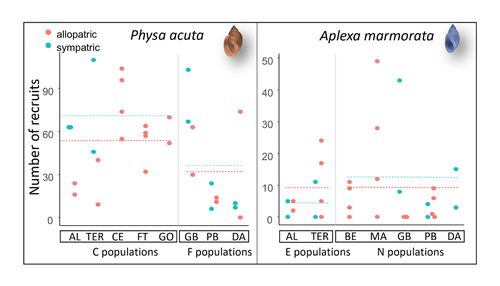

Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident speciesElodie Chapuis, Philippe Jarne, Patrice David https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.25.563987The evolution of a hobo snailRecommended by Ben Phillips based on reviews by David Reznick and 2 anonymous reviewersAt the very end of a paper entitled "Copepodology for the ornithologist" Hutchinson (1951) pointed out the possibility of 'fugitive species'. A fugitive species, said Hutchinson, is one that we would typically think of as competitively inferior. Wherever it happens to live it will eventually be overwhelmed by competition from another species. We would expect it to rapidly go extinct but for one reason: it happens to be a much better coloniser than the other species. Now all we need to explain its persistence is a dose of space and a little disturbance: a world in which there are occasional disturbances that cause local extinction of the dominant species. Now, argued Hutchinson, we have a recipe for persistence, albeit of a harried kind. As Hutchinson put it, fugitive species "are forever on the move, always becoming extinct in one locality as they succumb to competition, and always surviving as they reestablish themselves in some other locality." It is a fascinating idea, not just because it points to an interesting strategy, but also because it enriches our idea of competition: competition for space can be just as important as competition for time. Hutchinson's idea was independently discovered with the advent of metapopulation theory (Levins 1971; Slatkin 1974) and since then, of course, ecologists have gone looking, and they have unearthed many examples of species that could be said to have a fugitive lifestyle. These fugitive species are out there, but we don't often get to see them evolve. In their recent paper, Chapuis et al. (2024) make a convincing case that they have seen the evolution of a fugitive species. They catalog the arrival of an invasive freshwater snail on Guadeloupe in the Lesser Antilles, and they wonder what impact this snail's arrival might have on a native freshwater snail. This is a snail invasion, so it has been proceeding at a majestic pace, allowing the researchers to compare populations of the native snail that are completely naive to the invader with those that have been exposed to the invader for either a relatively short period (<20 generations) or longer periods (>20 generations). They undertook an extensive set of competition assays on these snails to find out which species were competitively superior and how the native species' competitive ability has evolved over time. Against naive populations of the native, the invasive snail turns out to be unequivocally the stronger competitor. (This makes sense; it probably wouldn't have been able to invade if it wasn't.) So what about populations of the native snail that have been exposed for longer, that have had time to adapt? Surprisingly these populations appear to have evolved to become even weaker competitors than they already were. So why is it that the native species has not simply been driven extinct? Drawing on their previous work on this system, the authors can explain this situation. The native species appears to be the better coloniser of new habitats. Thus, it appears that the arrival of the invasive species has pushed the native species into a different place along the competition-colonisation axis. It has sacrificed competitive ability in favour of becoming a better coloniser; it has become a fugitive species in its own backyard. This is a really nice empirical study. It is a large lab study, but one that makes careful sampling around a dynamic field situation. Thus, it is a lab study that informs an earlier body of fieldwork and so reveals a fascinating story about what is happening in the field. We are left not only with a particularly compelling example of character displacement towards a colonising phenotype but also with something a little less scientific: the image of a hobo snail, forever on the run, surviving in the spaces in between. References Chapuis E, Jarne P, David P (2024) Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident species. bioRxiv, 2023.10.25.563987, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.25.563987 Hutchinson, G.E. (1951) Copepodology for the Ornithologist. Ecology 32: 571–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/1931746 Levins, R., and D. Culver. (1971) Regional Coexistence of Species and Competition between Rare Species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 68, no. 6: 1246–48. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.68.6.1246. Slatkin, Montgomery. (1974) Competition and Regional Coexistence. Ecology 55, no. 1: 128–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1934625. | Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident species | Elodie Chapuis, Philippe Jarne, Patrice David | <p style="text-align: justify;">Biological invasions by phylogenetically and ecologically similar competitors pose an evolutionary challenge to native species. Cases of character displacement following invasions suggest that they can respond to th... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Species interactions | Ben Phillips | 2023-10-26 15:49:33 | View | |

18 Jan 2021

Trait plasticity and covariance along a continuous soil moisture gradientJ Grey Monroe, Haoran Cai, David L Des Marais https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.17.952853Another step towards grasping the complexity of the environmental response of traitsRecommended by Benoit Pujol based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersOne can only hope that one day, we will be able to evaluate how the ecological complexity surrounding natural populations affects their ability to adapt. This is more like a long term quest than a simple scientific aim. Many steps are heading in the right direction. This paper by Monroe and colleagues (2021) is one of them. References Gienapp P. & J.E. Brommer. 2014. Evolutionary dynamics in response to climate change. In: Charmentier A, Garant D, Kruuk LEB, editors. Quantitative genetics in the wild. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Oxford. pp. 254–273. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199674237.003.0015 | Trait plasticity and covariance along a continuous soil moisture gradient | J Grey Monroe, Haoran Cai, David L Des Marais | <p>Water availability is perhaps the greatest environmental determinant of plant yield and fitness. However, our understanding of plant-water relations is limited because it is primarily informed by experiments considering soil moisture variabilit... |  | Phenotypic Plasticity | Benoit Pujol | 2020-02-20 16:34:40 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer