Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▼ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

21 Feb 2023

Wolbachia genomics reveals a potential for a nutrition-based symbiosis in blood-sucking Triatomine bugsJonathan Filée, Kenny Agésilas-Lequeux, Laurie Lacquehay, Jean Michel Bérenger, Lise Dupont, Vagner Mendonça, João Aristeu da Rosa, Myriam Harry https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.06.506778Nutritional symbioses in triatomines: who is playing?Recommended by Natacha Kremer based on reviews by Alejandro Manzano Marín and Olivier DuronNearly 8 million people are suffering from Chagas disease in the Americas. The etiological agent, Trypanosoma cruzi, is mainly transmitted by triatomine bugs, also known as kissing or vampire bugs, which suck blood and transmit the parasite through their feces. Among these triatomine species, Rhodnius prolixus is considered the main vector, and many studies have focused on characterizing its biology, physiology, ecology and evolution. Interestingly, given that Rhodnius species feed almost exclusively on blood, their diet is unbalanced, and the insects can lack nutrients and vitamins that they cannot synthetize themself, such as B-vitamins. In all insects feeding exclusively on blood, symbioses with microbes producing B-vitamins (mainly biotin, riboflavin and folate) have been widely described (see review in Duron and Gottlieb 2020) and are critical for insect development and reproduction. These co-evolved relationships between blood feeders and nutritional symbionts could now be considered to develop new control methods, by targeting the ‘Achille’s heel’ of the symbiotic association (i.e., transfer of nutrient and / or control of nutritional symbiont density). But for this, it is necessary to better characterize the relationships between triatomines and their symbionts. R. prolixus is known to be associated with several symbionts. The extracellular gut symbiont Rhodococcus rhodnii, which reaches high bacterial densities and is almost fixed in R. prolixus populations, appears to be a nutritional symbiont under many blood sources. This symbiont can provide B-vitamins such as biotin (B7), niacin (B3), thiamin (B1), pyridoxin (B6) or riboflavin (B2) and can play an important role in the development and the reproduction of R. prolixus (Pachebat et al. (2013) and see review in Salcedo-Porras et al. (2020)). This symbiont is orally acquired through egg smearing, ensuring the fidelity of transmission of the symbiont from mother to offspring. However, as recently highlighted by Tobias et al. (2020) and Gilliland et al. (2022), other gut microbes could also participate to the provision of B-vitamins, and R. rhodnii could additionally provide metabolites (other than B-vitamins) increasing bug fitness. In the study from Filée et al., the authors focused on Wolbachia, an intracellular, maternally inherited bacterium, known to be a nutritional symbiont in other blood-sucking insects such as bedbugs (Nikoh et al. 2014), and its potential role in vitamin provision in triatomine bugs. After screening 17 different triatomine species from the 3 phylogenetic groups prolixus, pallescens and pictipes, they first show that Wolbachia symbionts are widely distributed in the different Rhodnius species. Contrary to R. rhodnii that were detected in all samples, Wolbachia prevalence was patchy and rarely fixed. The authors then sequenced, assembled, and compared 13 Wolbachia genomes from the infected Rhodnius species. They showed that all Wolbachia are phylogenetically positioned in the supergroup F that contains wCle (the Wolbachia from bedbugs). In addition, 8 Wolbachia strains (out of 12) encode a biotin operon under strong purifying selection, suggesting the preservation of the biological function and the metabolic potential of Wolbachia to supplement biotin in their Rhodnius host. From the study of insect genomes, the authors also evidenced several horizontal transfers of genes from Wolbachia to Rhodnius genomes, which suggests a complex evolutionary interplay between vampire bugs and their intracellular symbiont. This nice piece of work thus provides valuable information to the fields of multiple partners / nutritional symbioses and Wolbachia research. Dual symbioses described in insects feeding on unbalanced diets generally highlight a certain complementarity between symbionts that ensure the whole nutritional complementation. The study presented by Filée et al. leads rather to consider the impact of multiple symbionts with different lifestyles and transmission modes in the provision of a specific nutritional benefit (here, biotin). Because of the low prevalence of Wolbachia in certain species, a “ménage à trois” scenario would rather be replaced by an “open couple”, where the host relationship with new symbiotic partners (more or less stable at the evolutionary timescale) could provide benefits in certain ecological situations. The results also support the potential for Wolbachia to evolve rapidly along a continuum between parasitism and mutualism, by acquiring operons encoding critical pathways of vitamin biosynthesis. References Duron O. and Gottlieb Y. (2020) Convergence of Nutritional Symbioses in Obligate Blood Feeders. Trends in Parasitology 36(10):816-825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2020.07.007 Filée J., Agésilas-Lequeux K., Lacquehay L., Bérenger J.-M., Dupont L., Mendonça V., Aristeu da Rosa J. and Harry M. (2023) Wolbachia genomics reveals a potential for a nutrition-based symbiosis in blood-sucking Triatomine bugs. bioRxiv, 2022.09.06.506778, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.06.506778 Gilliland C.A. et al. (2022) Using axenic and gnotobiotic insects to examine the role of different microbes on the development and reproduction of the kissing bug Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Molecular Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16800 Nikoh et al. (2014) Evolutionary origin of insect–Wolbachia nutritional mutualism. PNAS. 111(28):10257-10262. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1409284111 Pachebat, J.A. et al. (2013). Draft genome sequence of Rhodococcus rhodnii strain LMG5362, a symbiont of Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae), the principle vector of Trypanosoma cruzi. Genome Announc. 1(3):e00329-13. https://doi.org/10.1128/genomea.00329-13 Salcedo-Porras N., et al. (2020). The role of bacterial symbionts in Triatomines: an evolutionary perspective. Microorganisms. 8:1438. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fmicroorganisms8091438 Tobias N.J., Eberhard F.E., Guarneri A.A. (2020) Enzymatic biosynthesis of B-complex vitamins is supplied by diverse microbiota in the Rhodnius prolixus anterior midgut following Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 3395-3401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2020.10.031 | Wolbachia genomics reveals a potential for a nutrition-based symbiosis in blood-sucking Triatomine bugs | Jonathan Filée, Kenny Agésilas-Lequeux, Laurie Lacquehay, Jean Michel Bérenger, Lise Dupont, Vagner Mendonça, João Aristeu da Rosa, Myriam Harry | <p>The nutritional symbiosis promoted by bacteria is a key determinant for adaptation and evolution of many insect lineages. A complex form of nutritional mutualism that arose in blood-sucking insects critically depends on diverse bacterial symbio... |  | Genome Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Species interactions | Natacha Kremer | Alejandro Manzano Marín | 2022-09-13 17:36:46 | View |

08 Nov 2021

Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression over development in the stick insect Timema californicumJelisaveta Djordjevic, Zoé Dumas, Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Tanja Schwander, Darren James Parker https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.23.427895Sex-biased gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect: pattern during development, extent, functions involved, rate of sequence evolution, and comparison with an holometabolous insectRecommended by Nadia Aubin-Horth based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersAn individual’s sexual phenotype is determined during development. Understanding which pathways are activated or repressed during the developmental stages leading to a sexually mature individual, for example by studying gene expression and how its level is biased between sexes, allows us to understand the functional aspects of dimorphic phenotypes between the sexes. Several studies have quantified the differences in transcription between the sexes in mature individuals, showing the extent of this sex-bias and which functions are affected. There is, however, less data available on what occurs during the different phases of development leading to this phenotype, especially in species with specific developmental strategies, such as hemimetabolous insects. While many well-studied insects such as the honey bee, drosophila, and butterflies, exhibit an holometabolous development ("holo" meaning "complete" in reference to their drastic metamorphosis from the juvenile to the adult stage), hemimetabolous insects have juvenile stages that look similar to the adult stage (the hemi prefix meaning "half", referring to the more tissue-specific changes during development), as seen in crickets, cockroaches, and stick insects. Learning more about what happens during development in terms of the identity of genes that are sex-biased (are they the same genes at different developmental stages? What are their function? Do they exhibit specific sequence evolution rates? Is one sex over-represented in the sex-biased genes?) and their quantity over developmental time (gradual or abrupt increase in number, if any?) would allow us to better understand the evolution of sexual dimorphism at the gene expression level and how it relates to dimorphism at the organismic level. Djordjevic et al (2021) studied the transcriptome during development in an hemimetabolous stick insect, to improve our knowledge of this type of development, where the organismic phenotype is already mostly present in the early life stages. To do this, they quantified whole-genome gene expression levels in whole insects, using RNA-seq at three different developmental stages. One of the interesting results presented by Djordjevic and colleagues is that the increase in the number of genes that were sex-biased in expression is gradual over the three stages of development studied and it is mostly the same genes that stay sex-biased over time, reflecting the gradual change in phenotypes between hatchlings, juveniles and adults. Furthermore, male-biased genes had faster sequence divergence rates than unbiased genes and that female-biased genes. This new information of sex-bias in gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect allowed the authors to do a comparison of sex-biased genes with what has been found in a well-studied holometabolous insect, Drosophila. The gene expression patterns showed that four times more genes were sex-biased in expression in that species than in stick insects. Furthermore, the increase in the number of sex-biased genes during development was quite abrupt and clearly distinct in the adult stage, a pattern that was not seen in stick insects. As pointed out by the authors, this pattern of a "burst" of sex-biased genes at maturity is more common than the gradual increase seen in stick insects. With this study, we now know more about the evolution of sex-biased gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect and how it relates to their phenotypic dimorphism. Clearly, the next step will be to sample more hemimetabolous species at different life stages, to see how this pattern is widespread or not in this mode of development in insects. References Djordjevic J, Dumas Z, Robinson-Rechavi M, Schwander T, Parker DJ (2021) Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression during development in the stick insect Timema californicum. bioRxiv, 2021.01.23.427895, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.23.427895 | Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression over development in the stick insect Timema californicum | Jelisaveta Djordjevic, Zoé Dumas, Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Tanja Schwander, Darren James Parker | <p style="text-align: justify;">Sexually dimorphic phenotypes are thought to arise primarily from sex-biased gene expression during development. Major changes in developmental strategies, such as the shift from hemimetabolous to holometabolous dev... |  | Evo-Devo, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Nadia Aubin-Horth | 2021-04-22 17:36:32 | View | |

16 Jun 2022

Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic beeRebecca A Boulton, Jeremy Field https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.29.478030Taking advantage of facultative sociality in sweat bees to study the developmental plasticity of antennal sense organs and its association with social phenotypeRecommended by Nadia Aubin-Horth based on reviews by Michael D Greenfield, Sylvia Anton and Lluís Socias-MartínezThe study of the evolution of sociality is closely associated with the study of the evolution of sensory systems. Indeed, group life and sociality necessitate that individuals recognize each other and detect outsiders, as seen in eusocial insects such as Hymenoptera. While we know that antennal sense organs that are involved in olfactory perception are found in greater densities in social species of that group compared to solitary hymenopterans, whether this among-species correlation represents the consequence of social evolution leading to sensory evolution, or the opposite, is still questioned. Knowing more about how sociality and sensory abilities covary within a species would help us understand the evolutionary sequence. Studying a species that shows social plasticity, that is facultatively social, would further allow disentangling the cause and consequence of social evolution and sensory systems and the implication of plasticity in the process. Boulton and Field (2022) studied a species of sweat bee that shows social plasticity, Halictus rubicundus. They studied populations at different latitudes in Great Britain: populations in the North are solitary, while populations in the south often show sociality, as they face a longer and warmer growing season, leading to the opportunity for two generations in a single year, a pre-condition for the presence of workers provisioning for the (second) brood. Using scanning electron microscope imaging, the authors compared the density of antennal sensilla types in these different populations (north, mid-latitude, south) to test for an association between sociality and olfactory perception capacities. They counted three distinct types of antennal sensilla: olfactory plates, olfactory hairs, and thermos/hygro-receptive pores, used to detect humidity, temperature and CO2. In addition, they took advantage of facultative sociality in this species by transplanting individuals from a northern population (solitary) to a southern location (where conditions favour sociality), to study how social plasticity is reflected (or not) in the density of antennal sensilla types. They tested the prediction that olfactory sensilla density is also developmentally plastic in this species. Their results show that antennal sensilla counts differ between the 3 studied regions (north, mid-latitude, south), but not as predicted. Individuals in the southern population were not significantly different from the mid-latitude and northern ones in their count of olfactory plates and they had less, not more, thermos/hygro receptors than mid-latitude and northern individuals. Furthermore, mid-latitude individuals had more olfactory hairs than the ones from the northern population and did not differ from southern ones. The prediction was that the individuals expressing sociality would have the highest count of these olfactory hairs. This unpredicted pattern based on the latitude of sampling sites may be due to the effect of temperature during development, which was higher in the mid-latitude site than in the southern one. It could also be the result of a genotype-by-environment interaction, where the mid-latitude population has a different developmental response to temperature compared to the other populations, a difference that is genetically determined (a different “reaction norm”). Reciprocal transplant experiments coupled with temperature measurements directly on site would provide interesting information to help further dissect this intriguing pattern. Interestingly, where a sweat bee developed had a significant effect on their antennal sensilla counts: individuals originating from the North that developed in the south after transplantation had significantly more olfactory hairs on their antenna than individuals from the same Northern population that developed in the North. This is in accordance with the prediction that the characteristics of sensory organs can also be plastic. However, there was no difference in antennal characteristics depending on whether these transplanted bees became solitary or expressed the social phenotype (foundress or worker). This result further supports the hypothesis that temperature affects development in this species and that these sensory characteristics are also plastic, although independently of sociality. Overall, the work of Boulton and Field underscores the importance of including phenotypic plasticity in the study of the evolution of social behaviour and provides a robust and fruitful model system to explore this further. References Boulton RA, Field J (2022) Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic bee. bioRxiv, 2022.01.29.478030, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.29.478030 | Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic bee | Rebecca A Boulton, Jeremy Field | <p style="text-align: justify;">The social Hymenoptera have contributed much to our understanding of the evolution of sensory systems. Attention has focussed chiefly on how sociality and sensory systems have evolved together. In the Hymenoptera, t... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Nadia Aubin-Horth | 2022-02-02 11:34:49 | View | |

04 Sep 2019

The discernible and hidden effects of clonality on the genotypic and genetic states of populations: improving our estimation of clonal ratesSolenn Stoeckel, Barbara Porro, Sophie Arnaud-Haond https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.09365v4How to estimate clonality from genetic data: use large samples and consider the biology of the speciesRecommended by Myriam Heuertz based on reviews by David Macaya-Sanz, Marcela Van Loo and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by David Macaya-Sanz, Marcela Van Loo and 1 anonymous reviewer

Population geneticists frequently use the genetic and genotypic information of a population sample of individuals to make inferences on the reproductive system of a species. The detection of clones, i.e. individuals with the same genotype, can give information on whether there is clonal (vegetative) reproduction in the species. If clonality is detected, population geneticists typically use genotypic richness R, the number of distinct genotypes relative to the sample size, to estimate the rate of clonality c, which can be defined as the proportion of reproductive events that are clonal. Estimating the rate of clonality based on genotypic richness is however problematic because, to date, there is no analytical, nor simulation-based, characterization of this relationship. Furthermore, the effect of sampling on this relationship has never been critically examined. References [1] Stoeckel, S., Porro, B., and Arnaud-Haond, S. (2019). The discernible and hidden effects of clonality on the genotypic and genetic states of populations: improving our estimation of clonal rates. ArXiv:1902.09365 [q-Bio] v4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1902.09365v4 | The discernible and hidden effects of clonality on the genotypic and genetic states of populations: improving our estimation of clonal rates | Solenn Stoeckel, Barbara Porro, Sophie Arnaud-Haond | <p>Partial clonality is widespread across the tree of life, but most population genetics models are conceived for exclusively clonal or sexual organisms. This gap hampers our understanding of the influence of clonality on evolutionary trajectories... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Myriam Heuertz | 2019-02-28 10:10:56 | View | |

05 Apr 2024

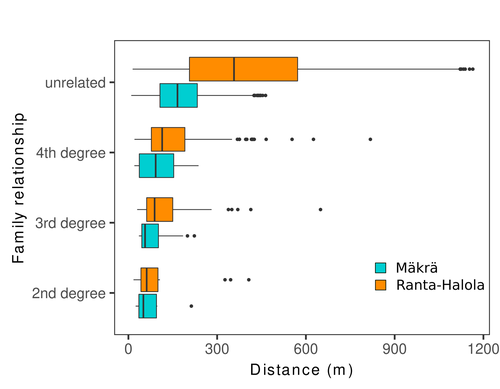

Does the seed fall far from the tree? Weak fine scale genetic structure in a continuous Scots pine populationAlina K. Niskanen, Sonja T. Kujala, Katri Kärkkäinen, Outi Savolainen, Tanja Pyhäjärvi https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.16.545344Weak spatial genetic structure in a large continuous Scots pine population – implications for conservation and breedingRecommended by Myriam Heuertz based on reviews by Joachim Mergeay, Jean-Baptiste Ledoux and Roberta Loh based on reviews by Joachim Mergeay, Jean-Baptiste Ledoux and Roberta Loh

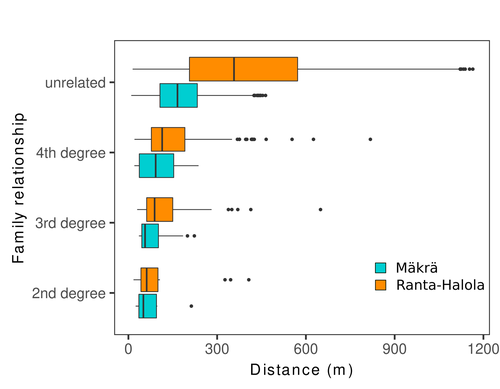

Spatial genetic structure, i.e. the non-random spatial distribution of genotypes, arises in populations because of different processes including spatially limited dispersal and selection. Knowledge on the spatial genetic structure of plant populations is important to assess biological parameters such as gene dispersal distances and the potential for local adaptations, as well as for applications in conservation management and breeding. In their work, Niskanen and colleagues demonstrate a multifaceted approach to characterise the spatial genetic structure in two replicate sites of a continuously distributed Scots pine population in South-Eastern Finland. They mapped and assessed the ages of 469 naturally regenerated adults and genotyped them using a SNP array which resulted in 157 325 filtered polymorphic SNPs. Their dataset is remarkably powerful because of the large numbers of both individuals and SNPs genotyped. This made it possible to characterise precisely the decay of genetic relatedness between individuals with spatial distance despite the extensive dispersal capacity of Scots pine through pollen, and ensuing expectations of an almost panmictic population. The authors’ data analysis was particularly thorough. They demonstrated that two metrics of pairwise relatedness, the genomic relationship matrix (GRM, Yang et al. 2011) and the kinship coefficient (Loiselle et al. 1995) were strongly correlated and produced very similar inference of family relationships: >99% of pairs of individuals were unrelated, and the remainder exhibited 2nd (e.g., half-siblings) to 4th degree relatedness. Pairwise relatedness decayed with spatial distance which resulted in extremely weak but statistically significant spatial genetic structure in both sites, quantified as Sp=0.0005 and Sp=0.0008. These estimates are at least an order of magnitude lower than estimates in the literature obtained in more fragmented populations of the same species or in other conifers. Estimates of the neighbourhood size, the effective number of potentially mating individuals belonging to a within-population neighbourhood (Wright 1946), were relatively large with Nb=1680-3210 despite relatively short gene dispersal distances, σg = 36.5–71.3m, which illustrates the high effective density of the population. The authors showed the implications of their findings for selection. The capacity for local adaptation depends on dispersal distances and the strength of the selection coefficient. In the study population, the authors inferred that local adaptation can only occur if environmental heterogeneity occurs over a distance larger than approximately one kilometre (or larger, if considering long-distance dispersal). Interestingly, in Scots pine, no local adaptation has been described on similar geographic scales, in contrast to some other European or Mediterranean conifers (Scotti et al. 2023). The authors’ results are relevant for the management of conservation and breeding. They showed that related individuals occurred within sites only and that they shared a higher number of rare alleles than unrelated ones. Since rare alleles are enriched in new and recessive deleterious variants, selecting related individuals could have negative consequences in breeding programmes. The authors also showed, in their response to reviewers, that their powerful dataset was not suitable to obtain a robust estimate of effective population size, Ne, based on the linkage disequilibrium method (Do et al. 2014). This illustrated that the estimation of Ne used for genetic indicators supported in international conservation policy (Hoban et al. 2020, CBD 2022) remains challenging in large and continuous populations (see also Santo-del-Blanco et al. 2023, Gargiulo et al. 2024). ReferencesCBD (2022) Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf Do C, Waples RS, Peel D, Macbeth GM, Tillett BJ, Ovenden JR (2014). NeEstimator v2: re-implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne ) from genetic data. Molecular Ecology Resources 14: 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12157 Gargiulo R, Decroocq V, González-Martínez SC, Paz-Vinas I, Aury JM, Kupin IL, Plomion C, Schmitt S, Scotti I, Heuertz M (2024) Estimation of contemporary effective population size in plant populations: limitations of genomic datasets. Evolutionary Applications, in press, https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.18.549323 Hoban S, Bruford M, D’Urban Jackson J, Lopes-Fernandes M, Heuertz M, Hohenlohe PA, Paz-Vinas I, et al. (2020) Genetic diversity targets and indicators in the CBD post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework must be improved. Biological Conservation 248: 108654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108654 Loiselle BA, Sork VL, Nason J & Graham C (1995) Spatial genetic structure of a tropical understorey shrub, Psychotria officinalis (Rubiaceae). American Journal of Botany 82: 1420–1425. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1995.tb12679.x Santos-del-Blanco L, Olsson S, Budde KB, Grivet D, González-Martínez SC, Alía R, Robledo-Arnuncio JJ (2022). On the feasibility of estimating contemporary effective population size (Ne) for genetic conservation and monitoring of forest trees. Biological Conservation 273: 109704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109704 Scotti I, Lalagüe H, Oddou-Muratorio S, Scotti-Saintagne C, Ruiz Daniels R, Grivet D, et al. (2023) Common microgeographical selection patterns revealed in four European conifers. Molecular Ecology 32: 393-411. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16750 Wright S (1946) Isolation by distance under diverse systems of mating. Genetics 31: 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/31.1.39 Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME & Visscher PM (2011) GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. The American Journal of Human Genetics 88: 76–82. https://www.cell.com/ajhg/pdf/S0002-9297(10)00598-7.pdf | Does the seed fall far from the tree? Weak fine scale genetic structure in a continuous Scots pine population | Alina K. Niskanen, Sonja T. Kujala, Katri Kärkkäinen, Outi Savolainen, Tanja Pyhäjärvi | <p>Knowledge of fine-scale spatial genetic structure, i.e., the distribution of genetic diversity at short distances, is important in evolutionary research and in practical applications such as conservation and breeding programs. In trees, related... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Population Genetics / Genomics | Myriam Heuertz | Joachim Mergeay | 2023-06-27 21:57:28 | View |

12 Nov 2021

How ancient forest fragmentation and riparian connectivity generate high levels of genetic diversity in a micro-endemic Malagasy treeJordi Salmona, Axel Dresen, Anicet E. Ranaivoson, Sophie Manzi, Barbara Le Pors, Cynthia Hong-Wa, Jacqueline Razanatsoa, Nicole V. Andriaholinirina, Solofonirina Rasoloharijaona, Marie-Elodie Vavitsara, Guillaume Besnard https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.25.394544An ancient age of open-canopy landscapes in northern Madagascar? Evidence from the population genetic structure of a forest treeRecommended by Miguel de Navascués based on reviews by Katharina Budde and Yurena Arjona based on reviews by Katharina Budde and Yurena Arjona

We currently live in the Anthropocene, the geological age characterized by a profound impact of human populations in the ecosystems and the environment. While there is little doubt about the action of humans in the shaping of present landscapes, it can be difficult to determine what the state of those landscapes was before humans started to modify them. This is the case of the Madagascar grasslands, whose origins have been debated with arguments proposing them either as anthropogenic, created with the arrival of humans around 2000BP, or as ancient features of the natural landscape with a forest fragmentation process due to environmental changes pre-dating human arrival [e.g. 1,2]. One way to clarify this question is through the genetic study of native species. Population continuity and fragmentation along time shape the structure of the genetic diversity in space. Species living in a uniform continuous habitat are expected to show genetic structuring determined only by geographical distance. Recent changes of the habitat can take many generations to reshape that genetic structure [3]. Thus, we expect genetic structure to reflect ancient features of the landscape. The work by Jordi Salmona and collaborators [4] studies the factors determining the population genetic structure of the Malagasy spiny olive (Noronhia spinifolia). This narrow endemic species is distributed in the discontinuous forest patches of the Loky-Manambato region (northern Madagascar). Jordi Salmona and collaborators genotyped 72 individuals distributed across the species distribution with restriction associated DNA sequencing and organelle microsatellite markers. Then, they studied the population genetic structure of the species. Using isolation-by-resistance models [5], they tested the influence of several landscape features (forest cover, roads, rivers, slope, etc.) on the connectivity between populations. Maternally inherited loci (chloroplast and mitochondria) and bi-parentally inherited loci (nuclear), were analysed separately in an attempt to identify the role of pollen and seed dispersal in the connectivity of populations. Despite the small distribution of the species, Jordi Salmona and collaborators [4] found remarkable levels of genetic diversity. The spatial structure of this diversity was found to be mainly explained by the forest cover of the landscape, suggesting that the landscape has been composed by patches of forests and grasslands for a long time. The main role of forest cover for the connectivity among populations also highlights the importance of riparian forest as dispersal corridors. Finally, differences between organelle and nuclear markers were not enough to establish any strong conclusion about the differences between pollen and seed dispersal. The results presented by Jordi Salmona and collaborators [4] contribute to the understanding of the history and ecology of understudied Madagascar ecosystems. Previous population genetic studies in some forest-dwelling mammals have been interpreted as supporting an old age for the fragmented landscapes in northern Madagascar [e.g. 1,6]. To my knowledge, this is the first study on a tree species. While this work might not completely settle the debate, it emphasizes the importance of studying a diversity of species to understand the biogeographic dynamics of a region. References 1. Quéméré, E., X. Amelot, J. Pierson, B. Crouau-Roy, L. Chikhi (2012) Genetic data suggest a natural prehuman origin of open habitats in northern Madagascar and question the deforestation narrative in this region. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of | How ancient forest fragmentation and riparian connectivity generate high levels of genetic diversity in a micro-endemic Malagasy tree | Jordi Salmona, Axel Dresen, Anicet E. Ranaivoson, Sophie Manzi, Barbara Le Pors, Cynthia Hong-Wa, Jacqueline Razanatsoa, Nicole V. Andriaholinirina, Solofonirina Rasoloharijaona, Marie-Elodie Vavitsara, Guillaume Besnard | <p>Understanding landscape changes is central to predicting evolutionary trajectories and defining conservation practices. While human-driven deforestation is intense throughout Madagascar, exception in areas like the Loky-Manambato region (North)... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Miguel de Navascués | 2020-11-27 09:07:21 | View | |

11 Mar 2020

Phylogenomic approaches reveal how a climatic inversion and glacial refugia shape patterns of diversity in an African rain forest tree speciesAndrew J. Helmstetter, Biowa E. N. Amoussou, Kevin Bethune, Narcisse G. Kandem, Romain Glèlè Kakaï, Bonaventure Sonké, Thomas L. P. Couvreur https://doi.org/10.1101/807727Remarkable insights into processes shaping African tropical tree diversityRecommended by Michael Pirie based on reviews by Miguel de Navascués, Lars Chatrou and Oscar Vargas based on reviews by Miguel de Navascués, Lars Chatrou and Oscar Vargas

Tropical biodiversity is immense, under enormous threat, and yet still poorly understood. Global climatic breakdown and habitat destruction are impacting on and removing this diversity before we can understand how the biota responds to such changes, or even fully appreciate what we are losing [1]. This is particularly the case for woody shrubs and trees [2] and for the flora of tropical Africa [3]. Helmstetter et al. [4] have taken a significant step to improve our understanding of African tropical tree diversity in the context of past climatic change. They have done so by means of a remarkably in-depth analysis of one species of the tropical plant family Annonaceae: Annickia affinis [5]. A. affinis shows a distribution pattern in Africa found in various plant (but interestingly not animal) groups: a discontinuity between north and south of the equator [6]. There is no obvious physical barrier to cause this discontinuity, but it does correspond with present day distinct northern and southern rainy seasons. Various explanations have been proposed for this discontinuity, set out as hypotheses to be tested in this paper: climatic fluctuations resulting in changes in plant distributions in the Pleistocene, or differences in flowering times or in ecological niche between northerly and southerly populations. These explanations are not mutually exclusive, but they can be tested using phylogenetic inference – if you can sample variable enough sequence data from enough individuals – complemented with analysis of ecological niches and traits. Using targeted sequence capture, the authors amassed a dataset representing 351 nuclear markers for 112 individuals of A. affinis. This dataset is impressive for a number of reasons: First, sampling such a species across such a wide range in tropical Africa presents numerous challenges of itself. Second, the technical achievement of using this still relatively new sequencing technique with a custom set of baits designed specifically for this plant family [7] is also considerable. The result is a volume of data that just a few years ago would not have been feasible to collect, and which now offers the possibility to meaningfully analyse DNA sequence variation within a species across numerous independent loci of the nuclear genome. This is the future of our research field, and the authors have ably demonstrated some of its possibilities. Using this data, they performed on the one hand different population genetic clustering approaches, and on the other, different phylogenetic inference methods. I would draw attention to their use and comparison of coalescence and network-based approaches, which can account for the differences between gene trees that might be expected between populations of a single species. The results revealed four clades and a consistent sequence of divergences between them. The authors inferred past shifts in geographic range (using a continuous state phylogeographic model), depicting a biogeographic scenario involving a dispersal north over the north/south discontinuity; and demographic history, inferring in some (but not all) lineages increases in effective population size around the time of the last glacial maximum, suggestive of expansion from refugia. Using georeferenced specimen data, they compared ecological niches between populations, discovering that overlap was indeed smallest comparing north to south. Just the phenology results were effectively inconclusive: far better data on flowering times is needed than can currently be harvested from digitised herbarium specimens. Overall, the results add to the body of evidence for the impact of Pleistocene climatic changes on population structure, and for niche differences contributing to the present day north/south discontinuity. However, they also paint a complex picture of idiosyncratic lineage-specific responses, even within a single species. With the increasing accessibility of the techniques used here we can look forward to more such detailed analyses of independent clades necessary to test and to expand on these conclusions, better to understand the nature of our tropical plant diversity while there is still opportunity to preserve it for future generations. References [1] Mace, G. M., Gittleman, J. L., and Purvis, A. (2003). Preserving the Tree of Life. Science, 300(5626), 1707–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1085510 | Phylogenomic approaches reveal how a climatic inversion and glacial refugia shape patterns of diversity in an African rain forest tree species | Andrew J. Helmstetter, Biowa E. N. Amoussou, Kevin Bethune, Narcisse G. Kandem, Romain Glèlè Kakaï, Bonaventure Sonké, Thomas L. P. Couvreur | <p>The world’s second largest expanse of tropical rain forest is in Central Africa and it harbours enormous species diversity. Population genetic studies have consistently revealed significant structure across central African rain forest plants, i... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Michael Pirie | 2019-10-29 15:19:36 | View | |

16 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Evolutionary robotics simulations help explain why reciprocity is rare in nature.André J-B, Nolfi S 10.1038/srep32785Simulated robots and the evolution of reciprocityRecommended by Michael D Greenfield and Joël Meunier

Of the various forms of cooperative and altruistic behavior, reciprocity remains the most contentious. Humans certainly exhibit reciprocity – under certain circumstances – and various non-human animals behave in ways suggesting that they do as well. Thus, evolutionary biologists have sought to explain why non-relatives might engage in altruistic transactions when a substantial delay occurs between helping and compensation; i.e. an individual may be a donor today and a beneficiary tomorrow, or vice-versa. This quest, aided by game theory and computer modeling late in the past century, identified some strategies for reciprocal behavior that could work – in theory. But when biologists looked for confirmation of these strategies in animals they found little evidence that stood up to rigorous testing. In a recent paper André and Nolfi [1] offer a compelling reason for this observed rarity of reciprocity: Reciprocal behavior that animals might exhibit is a bit more complex than any of the game theoretic strategies, and even the simplest forms of realistic behavior would entail several nearly simultaneous mutations, an unlikely occurrence. André and Nolfi [1] relied on neural networks to test actors, robots that could evolve helping and reciprocal behavior from a basal level of selfishness. In an extensive series of simulations, they found that reciprocal behavior did not take hold in a population, largely because the various intermediates to full reciprocity were eliminated before the subsequent mutations occurred. The findings are satisfying given our current knowledge of animal behavior, but questions remain. Notably, how does one account for those rare cases in which reciprocity does meet all the criteria? The authors suggest some possibilities, but an analysis will await their next study. Reference [1] André J-B, Nolfi S. 2016. Evolutionary robotics simulations help explain why reciprocity is rare in nature. Scientific Reports 6:32785. doi: 10.1038/srep32785 | Evolutionary robotics simulations help explain why reciprocity is rare in nature. | André J-B, Nolfi S | The relative rarity of reciprocity in nature, contrary to theoretical predictions that it should be widespread, is currently one of the major puzzles in social evolution theory. Here we use evolutionary robotics to solve this puzzle. We show tha... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Theory | Michael D Greenfield | 2016-12-16 18:08:31 | View | |

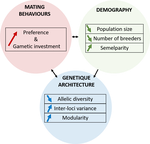

18 Nov 2020

A demogenetic agent based model for the evolution of traits and genome architecture under sexual selectionLouise Chevalier, François de Coligny, Jacques Labonne https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.01.014514Sexual selection goes dynamicRecommended by Michael D Greenfield based on reviews by Frédéric Guillaume and 1 anonymous reviewer150 years after Darwin published ‘Descent of man and selection in relation to sex’ (Darwin, 1871), the evolutionary mechanism that he laid out in his treatise continues to fascinate us. Sexual selection is responsible for some of the most spectacular traits among animals, and plants, and it appeals to our interest in all things reproductive and sexual (Bell, 1982). In addition, sexual selection poses some of the more intractable problems in evolutionary biology: Its realm encompasses traits that are subject to markedly different selection pressures, particularly when distinct, yet associated, traits tend to be associated with males, e.g. courtship signals, and with females, e.g. preferences (cf. Ah-King & Ahnesjo, 2013). While separate, such traits cannot evolve independently of each other (Arnqvist & Rowe, 2005), and complex feedback loops and correlations between them are predicted (Greenfield et al., 2014). Traditionally, sexual selection has been modelled under simplifying assumptions, and quantitative genetic approaches that avoided evolutionary dynamics have prevailed. New computing methods may be able to free the field from these constraints, and a trio of theoreticians (Chevalier, De Coligny & Labonne 2020) describe here a novel application of a ‘demo-genetic agent (or individual) based model’, a mouthful hereafter termed DG-ABM, for arriving at a holistic picture of the sexual selection trajectory. The application is built on the premise that traits, e.g. courtship, preference, gamete investment, competitiveness for mates, can influence the genetic architecture, e.g. correlations, of those traits. In turn, the genetic architecture can influence the expression and evolvability of the traits. Much of this influence occurs via demographic features, i.e. social environment, generated by behavioral interactions during sexual advertisement, courtship, mate guarding, parental care, post-mating dispersal, etc. References Ah-King, M. and Ahnesjo, I. 2013. The ‘sex role’ concept: An overview and evaluation Evolutionary Biology, 40, 461-470. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11692-013-9226-7 | A demogenetic agent based model for the evolution of traits and genome architecture under sexual selection | Louise Chevalier, François de Coligny, Jacques Labonne | <p>Sexual selection has long been known to favor the evolution of mating behaviors such as mate preference and competitiveness, and to affect their genetic architecture, for instance by favoring genetic correlation between some traits. Reciprocall... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics, Sexual Selection | Michael D Greenfield | 2020-04-02 14:44:25 | View | |

29 Nov 2023

Does sociality affect evolutionary speed?Lluís Socias-Martínez, Louise Rachel Peckre https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10086186On the evolutionary implications of being a social animalRecommended by Michael D Greenfield based on reviews by Rafael Lucas Rodriguez and 1 anonymous reviewerWhat does it mean to be highly social? Considering the so-called four ‘pinnacles’ of animal society (Wilson, 1975) – humans, cooperative breeding as found in some non-human mammals and birds, the social insects, and colonial marine invertebrates – having inter-individual relations extending beyond the sexual pair and the parent-offspring interaction is foremost. In many cases being social implies a high local population density, interaction with the same group of individuals over an extended time period, and an overlapping of generations. Additional features of social species may be a wide geographical range, perhaps associated with ecological and behavioral plasticity, the latter often facilitated by cultural transmission of traditions. Narrowing our perspective to the domain of PCI Evolutionary Biology, we might continue our question by asking whether being social predisposes one to a special evolutionary path toward the future. Do social species evolve faster (or slower) than their more solitary relatives such that over time they are more unlike (or similar to) those relatives (anagenesis)? And are evolutionary changes in social species more or less likely to be accompanied by lineage splitting (cladogenesis) and ultimately speciation? The latter question is parallel to one first posed over 40 years ago (West-Eberhard, 1979; Lande, 1981) for sexually selected traits: Do strong mating preferences and conspicuous courtship signals generate speciation via the Fisherian process or ecological divergence? An extensive survey of birds had found little supporting evidence (Price, 1998), but a recent one that focused on plumage complexity in tanagers did reveal a relationship, albeit a weak one (Price-Waldman et al., 2020). Because sexual selection has been viewed as a part of the broader process of social selection (West-Eberhard, 1979), it is thus fitting to extend our surveys to the evolutionary implications of being social. Unlike the inquiry for a sexual selection - evolutionary change connection, a social behavior counterpart has remained relatively untreated. Diverse logistical problems might account for this oversight. What objective proxies can be used for social behavior, and for the rate of evolutionary change within a lineage? How many empirical studies have generated data from which appropriate proxies could be extracted? More intractable is the conundrum arising from the connectedness between socially- and sexually-selected traits. For example, the elevated population density found in highly social species can greatly increase the mating advantage enjoyed by an attractive male. If anagenesis is detected, did it result from social behavior or sexual selection? And if social behavior leads to a group structure in which male-male competition is reduced, would a modest rate of evolutionary change be support for the sexual selection - evolutionary speed connection or evidence opposing the sociality - evolution one? Against the above odds, several biologists have begun to explore the notion that social behavior just might favor evolutionary speed in either anagenesis or cladogenesis. In a recent analysis relying on the comparative method, Lluís Socias-Martínez and Louise Rachel Peckre (2023) combed the scientific literature archives and identified those studies with specific data on the relationships between sexual selection or social behavior and evolutionary change, either anagenesis or cladogenesis. The authors were careful to employ fairly conservative criteria for including studies, and the number eventually retained was small. Nonetheless, some patterns emerge: Many more studies report anagenesis than cladogenesis, and many more report correlations with sexually-selected traits than with non-sexual social behavior ones. And, no study indicates a potential effect of social behavior on cladogenesis. Is this latter observation authentic or an artifact of a paucity of data? There are some a priori reasons why cladogenesis may seldom arise. Whereas highly social behavior could lead to fission encompassing mutually isolated population clusters within a species, social behavior may also engender counterbalancing plasticity that allows and even promotes inter-cluster migration and fusion. And briefly – and non-systematically, as the rate of lineage splitting would need to be measured – looking at one of the pinnacles of animal social behavior, the social insects, there is little indication that diversification has been accelerated. There are fewer than 3000 described species of termites, only ca. 16,000 ants, and the vast majority of bees and wasps are solitary. Lluís Socias-Martínez and Louise Rachel Peckre provide us with a very detailed discussion of these and a myriad of other complications. I end with a common refrain, we need more consideration of the authors’ interesting question, and much more data and analysis. One can thank Socias-Martínez and Peckre for pointing us in that direction. References Lande, R. (1981). Models of speciation by sexual selection on polygenic traits. Proc. Natn. Acad. Sci. USA 78, 3721-3725. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.78.6.3721 Price, T. (1998). Sexual selection and natural selection in bird speciation. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. B, 353, 251-260. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1998.0207 Price‐Waldman, R. M., Shultz, A. J., & Burns, K. J. (2020). Speciation rates are correlated with changes in plumage color complexity in the largest family of songbirds. Evolution, 74(6), 1155–1169. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13982 Socias-Martínez and Peckre. (2023). Does sociality affect evolutionary speed? Zenodo, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10086186 West-Eberhard, M. J. (1979). Sexual selection, social competition, and evolution. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 123(4), 222–234. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2828804 Wilson, E. O. (1975). Sociobiology. The New Synthesis. Cambridge, Mass., The Belknap Press of Harvard University | Does sociality affect evolutionary speed? | Lluís Socias-Martínez, Louise Rachel Peckre | <p>An overlooked source of variation in evolvability resides in the social lives of animals. In trying to foster research in this direction, we offer a critical review of previous work on the link between evolutionary speed and sociality. A first ... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Sexual Selection, Speciation | Michael D Greenfield | 2023-03-03 00:10:49 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer