Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▼ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

13 Jan 2019

Why cooperation is not running awayFélix Geoffroy, Nicolas Baumard, Jean-Baptiste André https://doi.org/10.1101/316117A nice twist on partner choice theoryRecommended by Erol Akcay based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersIn this paper, Geoffroy et al. [1] deal with partner choice as a mechanism of maintaining cooperation, and argues that rather than being unequivocally a force towards improved payoffs to everyone through cooperation, partner choice can lead to “over-cooperation” where individuals can evolve to invest so much in cooperation that the costs of cooperating partially or fully negate the benefits from it. This happens when partner choice is consequential and effective, i.e., when interactions are long (so each decision to accept or reject a partner is a bigger stake) and when meeting new partners is frequent when unpaired (so that when one leaves an interaction one can find a new partner quickly). Geoffroy et al. [1] show that this tendency to select for overcooperation under such regimes can be counteracted if individuals base their acceptance-rejection of partners not just on the partner cooperativeness, but also on their own. By using tools from matching theory in economics, they show that plastic partner choice generates positive assortment between cooperativeness of the partners, and in the extreme case of perfectly assortative pairings, makes the pair the unit of selection, which selects for maximum total payoff. References [1] Geoffroy, F., Baumard, N., & Andre, J.-B. (2019). Why cooperation is not running away. bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/316117 | Why cooperation is not running away | Félix Geoffroy, Nicolas Baumard, Jean-Baptiste André | <p>A growing number of experimental and theoretical studies show the importance of partner choice as a mechanism to promote the evolution of cooperation, especially in humans. In this paper, we focus on the question of the precise quantitative lev... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Theory | Erol Akcay | 2018-05-15 10:32:51 | View | |

12 Jul 2017

Despite reproductive interference, the net outcome of reproductive interactions among spider mite species is not necessarily costlySalomé H. Clemente, Inês Santos, Rita Ponce, Leonor R. Rodrigues, Susana A. M. Varela and Sara Magalhães 10.1101/113274The pros and cons of mating with strangersRecommended by Vincent Calcagno based on reviews by Joël Meunier and Michael D Greenfield

Interspecific matings are by definition rare events in nature, but when they occur they can be very important, and not only because they might condition gene flow between species. Even when such matings have no genetic consequence, for instance if they do not yield any fertile hybrid offspring, they can still have an impact on the population dynamics of the species involved [1]. Such atypical pairings between heterospecific partners are usually regarded as detrimental or undesired; as they interfere with the occurrence or success of intraspecific matings, they are expected to cause a decline in absolute fitness. References [1] Gröning J. & Hochkirch A. 2008. Reproductive interference between animal species. The Quarterly Review of Biology 83: 257-282. doi: 10.1086/590510 [2] Clemente SH, Santos I, Ponce AR, Rodrigues LR, Varela SAM & Magalhaes S. 2017 Despite reproductive interference, the net outcome of reproductive interactions among spider mite species is not necessarily costly. bioRxiv 113274, ver. 4 of the 30th of June 2017. doi: 10.1101/113274 | Despite reproductive interference, the net outcome of reproductive interactions among spider mite species is not necessarily costly | Salomé H. Clemente, Inês Santos, Rita Ponce, Leonor R. Rodrigues, Susana A. M. Varela and Sara Magalhães | Reproductive interference is considered a strong ecological force, potentially leading to species exclusion. This supposes that the net effect of reproductive interactions is strongly negative for one of the species involved. Testing this requires... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Vincent Calcagno | 2017-03-06 11:48:08 | View | |

28 Feb 2018

Insects and incest: sib-mating tolerance in natural populations of a parasitoid waspMarie Collet, Isabelle Amat, Sandrine Sauzet, Alexandra Auguste, Xavier Fauvergue, Laurence Mouton, Emmanuel Desouhant https://doi.org/10.1101/169268Incestuous insects in nature despite occasional fitness costsRecommended by Caroline Nieberding and Bertanne Visser based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersInbreeding, or mating between relatives, generally lowers fitness [1]. Mating between genetically similar individuals can result in higher levels of homozygosity and consequently a higher frequency with which recessive disease alleles may be expressed within a population. Reduced fitness as a consequence of inbreeding, or inbreeding depression, can vary between individuals, sexes, populations and species [2], but remains a pervasive challenge for many organisms with small local population sizes, including humans [3]. But all is not lost for individuals within small populations, because an array of mechanisms can be employed to evade the negative effects of inbreeding [4], including sib-mating avoidance and dispersal [5, 6]. Despite thorough investigation of inbreeding and sib-mating avoidance in the laboratory, only very few studies have ventured into the field besides studies on vertebrates and eusocial insects. The study of Collet et al. [7] is a surprising exception, where the effect of male density and frequency of relatives on inbreeding avoidance was tested in the laboratory, after which robust field collections and microsatellite genotyping were used to infer relatedness and dispersal in natural populations. The parasitic wasp Venturia canescens is an excellent model system to study inbreeding, because mating success was previously found to decrease with increasing relatedness between mates in the laboratory [8] and this species thus suffers from inbreeding depression [9–11]. The authors used an elegant design combining population genetics and model simulations to estimate relatedness of mating partners in the field and compared that with a theoretical distribution of potential mate encounters when random mating is assumed. One of the most important findings of this study is that mating between siblings is not avoided in this species in the wild, despite negative fitness effects when inbreeding does occur. Similar findings were obtained for another insect species, the field cricket Gryllus campestris [12], which leaves us to wonder whether inbreeding tolerance could be more common in nature than currently appreciated. The authors further looked into sex-specific dispersal patterns between two patches located a few hundred meters apart. Females were indeed shown to be more related within a patch, but no genetic differences were observed between males, suggesting that V. canescens males more readily disperse. Moreover, microsatellite data at 18 different loci did not reveal genetic differentiation between populations approximately 300 kilometers apart. Gene flow is thus occurring over considerable distances, which could play an important role in the ability of this species to avoid negative fitness consequences of inbreeding in nature. Another interesting aspect of this work is that discrepancies were found between laboratory- and field-based data. What is the relevance of laboratory-based experiments if they cannot predict what is happening in the wild? Many, if not most, biologists (including us) bring our model system into the laboratory to control, at least to some extent, the plethora of environmental factors that could potentially affect our system (in ways that we do not want). Most behavioral studies on mating patterns and sexual selection are conducted in standardized laboratory conditions, but sexual selection is in essence social selection, because an individual’s fitness is partly determined by the phenotype of its social partners (i.e. the social environment) [13]. The social environment may actually dictate the expression of female mate choice and it is unclear how potential laboratory-induced social biases affect mating outcome. In V. canescens, findings using field-caught individuals paint a completely opposite picture of what was previously shown in the laboratory, i.e. sib-avoidance is not taking place in the field. It is likely that density, level of relatedness, sex ratio in the field, and/or the size of experimental arenas in the lab are all factors affecting mate selectivity, as we have previously shown in a butterfly [14–16]. If females, for example, typically only encounter a few males in sequence in the wild, it may be problematic for them to express choosiness when confronted simultaneously with two or more males in the laboratory. A recent study showed that, in the wild, female moths take advantage of staying in groups to blur male choosiness [17]. It is becoming more and more clear that what we observe in the laboratory may not actually reflect what is happening in nature [18]. Instead of ignoring the species-specific life history and ecological features of our favorite species when conducting lab experiments, we suggest that it is time to accept that we now have the theoretical foundations to tease apart what in this “environmental noise” actually shapes sexual selection in nature. Explicitly including ecology in studies on sexual selection will allow us to make more meaningful conclusions, i.e. rather than “this is what may happen in the wild”, we would be able to state “this is what often happens in nature”. References [1] Charlesworth D & Willis JH. 2009. The genetics of inbreeding depression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10: 783–796. doi: 10.1038/nrg2664 | Insects and incest: sib-mating tolerance in natural populations of a parasitoid wasp | Marie Collet, Isabelle Amat, Sandrine Sauzet, Alexandra Auguste, Xavier Fauvergue, Laurence Mouton, Emmanuel Desouhant | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (http://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100047) 1. Sib-mating avoidance is a pervasive behaviour that likely evolves in species subject to inbreeding dep... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Sexual Selection | Caroline Nieberding | 2017-07-28 09:23:20 | View | |

31 Oct 2022

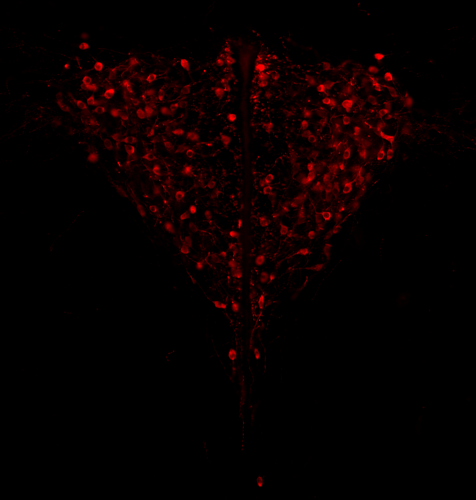

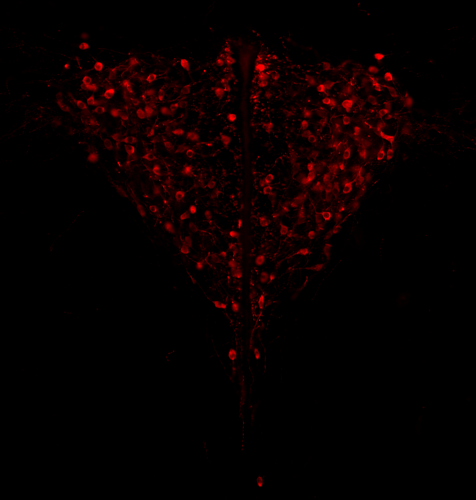

Genotypic sex shapes maternal care in the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoidesLouise D Heitzmann, Marie Challe, Julie Perez, Laia Castell, Evelyne Galibert, Agnes Martin, Emmanuel Valjent, Frederic Veyrunes https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.05.487174Effect of sex chromosomes on mammalian behaviour: a case study in pygmy miceRecommended by Gabriel Marais and Trine Bilde based on reviews by Marion Anne-Lise Picard, Caroline Hu and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Marion Anne-Lise Picard, Caroline Hu and 1 anonymous reviewer

In mammals, it is well documented that sexual dimorphism and in particular sex differences in behaviour are fine-tuned by gonadal hormonal profiles. For example, in lemurs, where female social dominance is common, the level of testosterone in females is unusually high compared to that of other primate females (Petty and Drea 2015). Recent studies however suggest that gonadal hormones might not be the only biological factor involved in establishing sexual dimorphism, sex chromosomes might also play a role. The four core genotype (FCG) model and other similar systems allowing to decouple phenotypic and genotypic sex in mice have provided very convincing evidence of such a role (Gatewood et al. 2006; Arnold and Chen 2009; Arnold 2020a, 2020b). This however is a new field of research and the role of sex chromosomes in establishing sexually dimorphic behaviours has not been studied very much yet. Moreover, the FCG model has some limits. Sry, the male determinant gene on the mammalian Y chromosome might be involved in some sex differences in neuroanatomy, but Sry is always associated with maleness in the FCG model, and this potential role of Sry cannot be studied using this system. Heitzmann et al. have used a natural system to approach these questions. They worked on the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoides, in which a modified X chromosome called X* can feminize X*Y individuals, which offers a great opportunity for elegant experiments on the effects of sex chromosomes versus hormones on behaviour. They focused on maternal care and compared pup retrieval, nest quality, and mother-pup interactions in XX, X*X and X*Y females. They found that X*Y females are significantly better at retrieving pups than other females. They are also much more aggressive towards the fathers than other females, preventing paternal care. They build nests of poorer quality but have similar interactions with pups compared to other females. Importantly, no significant differences were found between XX and X*X females for these traits, which points to an effect of the Y chromosome in explaining the differences between X*Y and other females (XX, X*X). Also, another work from the same group showed similar gonadal hormone levels in all the females (Veyrunes et al. 2022). Heitzmann et al. made a number of predictions based on what is known about the neuroanatomy of rodents which might explain such behaviours. Using cytology, they looked for differences in neuron numbers in the hypothalamus involved in the oxytocin, vasopressin and dopaminergic pathways in XX, X*X and X*Y females, but could not find any significant effects. However, this part of their work relied on very small sample sizes and they used virgin females instead of mothers for ethical reasons, which greatly limited the analysis. Interestingly, X*Y females have a higher reproductive performance than XX and X*X ones, which compensate for the cost of producing unviable YY embryos and certainly contribute to maintaining a high frequency of X* in many African pygmy mice populations (Saunders et al. 2014, 2022). X*Y females are probably solitary mothers contrary to other females, and Heitzmann et al. have uncovered a divergent female strategy in this species. Their work points out the role of sex chromosomes in establishing sex differences in behaviours. References Arnold AP (2020a) Sexual differentiation of brain and other tissues: Five questions for the next 50 years. Hormones and Behavior, 120, 104691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2020.104691 Arnold AP (2020b) Four Core Genotypes and XY* mouse models: Update on impact on SABV research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 119, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.09.021 Arnold AP, Chen X (2009) What does the “four core genotypes” mouse model tell us about sex differences in the brain and other tissues? Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 30, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.11.001 Gatewood JD, Wills A, Shetty S, Xu J, Arnold AP, Burgoyne PS, Rissman EF (2006) Sex Chromosome Complement and Gonadal Sex Influence Aggressive and Parental Behaviors in Mice. Journal of Neuroscience, 26, 2335–2342. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3743-05.2006 Heitzmann LD, Challe M, Perez J, Castell L, Galibert E, Martin A, Valjent E, Veyrunes F (2022) Genotypic sex shapes maternal care in the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoides. bioRxiv, 2022.04.05.487174, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.05.487174 Petty JMA, Drea CM (2015) Female rule in lemurs is ancestral and hormonally mediated. Scientific Reports, 5, 9631. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09631 Saunders PA, Perez J, Rahmoun M, Ronce O, Crochet P-A, Veyrunes F (2014) Xy Females Do Better Than the Xx in the African Pygmy Mouse, Mus Minutoides. Evolution, 68, 2119–2127. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12387 Saunders PA, Perez J, Ronce O, Veyrunes F (2022) Multiple sex chromosome drivers in a mammal with three sex chromosomes. Current Biology, 32, 2001-2010.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.03.029 Veyrunes F, Perez J, Heitzmann L, Saunders PA, Givalois L (2022) Separating the effects of sex hormones and sex chromosomes on behavior in the African pygmy mouse Mus minutoides, a species with XY female sex reversal. bioRxiv, 2022.07.11.499546. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.11.499546 | Genotypic sex shapes maternal care in the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoides | Louise D Heitzmann, Marie Challe, Julie Perez, Laia Castell, Evelyne Galibert, Agnes Martin, Emmanuel Valjent, Frederic Veyrunes | <p>Sexually dimorphic behaviours, such as parental care, have long been thought to be driven mostly, if not exclusively, by gonadal hormones. In the past two decades, a few studies have challenged this view, highlighting the direct influence of th... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Reproduction and Sex | Gabriel Marais | 2022-04-08 20:09:58 | View | |

20 Sep 2017

An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in DrosophilaErika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery 10.1101/143560Cancer and loneliness in DrosophilaRecommended by Ana Rivero based on reviews by Ana Rivero and Silvie HuijbenDrosophila flies may not be perceived as a quintessentially social animal, particularly when compared to their eusocial hymenopteran cousins. Although they have no parental care, division of labour or subfertile caste, fruit flies nevertheless exhibit an array of social phenotypes that are potentially comparable to those of their highly social relatives. In the wild, Drosophila adults cluster around food resources where courtship, mating activity and oviposition occur. Recent work has shown not only that social interactions in these clusters condition many aspects of the behaviour and physiology of the flies [1] but also, and perhaps more unexpectedly, that social isolation has a negative impact on their fitness [2]. Many studies in humans point to the role of social isolation as a source of stress that can induce and accelerate disease progression. The ultimate proof of the connection between social interaction and disease is however mired in confounding variables and alternative explanations so the subject, though crucial, remains controversial. With a series of elegant experiments using Drosophila flies that develop an inducible form of intestinal cancer, Dawson et al [3] show that cancer progresses more rapidly in flies maintained in isolation than in flies maintained with other cancerous flies. Further, cancerous flies kept with non-cancerous flies, fare just as badly as when kept alone. Their experiments suggest that this is due to the combined effect of healthy flies avoiding contact with cancerous flies (even though this is a non-contagious disease), and of cancerous flies having higher quality interactions with other cancerous flies than with healthy ones. Perceived isolation is therefore as pernicious as real isolation when it comes to cancer progression in these flies. Like all good research, this study opens up as many questions as it answers, in particular the why and wherefores of the flies’ extraordinary social behaviour in the face of disease. References [1] Camiletti AL and Thompson GJ. 2016. Drosophila as a genetically tractable model for social insect behavior. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 4: 40. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2016.00040 [2] Ruan H and Wu C-F. 2008. Social interaction-mediated lifespan extension of Drosophila Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 105: 7506-7510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711127105 [3] Dawson E, Bailly T, Dos Santos J, Moreno C, Devilliers M, Maroni B, Sueur C, Casali A, Ujvari B, Thomas F, Montagne J, Mery F. 2017. An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila. BiorXiv, 143560, ver. 3 of 19th September 2017. doi: 10.1101/143560 | An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila | Erika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery | The ecological benefits of sociality in gregarious species are widely acknowledged. However, only limited data is available on how the social environment influences non-communicable disease outcomes. For instance, despite extensive research over t... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Ana Rivero | 2017-05-30 08:55:16 | View | |

16 Jun 2022

Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic beeRebecca A Boulton, Jeremy Field https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.29.478030Taking advantage of facultative sociality in sweat bees to study the developmental plasticity of antennal sense organs and its association with social phenotypeRecommended by Nadia Aubin-Horth based on reviews by Michael D Greenfield, Sylvia Anton and Lluís Socias-MartínezThe study of the evolution of sociality is closely associated with the study of the evolution of sensory systems. Indeed, group life and sociality necessitate that individuals recognize each other and detect outsiders, as seen in eusocial insects such as Hymenoptera. While we know that antennal sense organs that are involved in olfactory perception are found in greater densities in social species of that group compared to solitary hymenopterans, whether this among-species correlation represents the consequence of social evolution leading to sensory evolution, or the opposite, is still questioned. Knowing more about how sociality and sensory abilities covary within a species would help us understand the evolutionary sequence. Studying a species that shows social plasticity, that is facultatively social, would further allow disentangling the cause and consequence of social evolution and sensory systems and the implication of plasticity in the process. Boulton and Field (2022) studied a species of sweat bee that shows social plasticity, Halictus rubicundus. They studied populations at different latitudes in Great Britain: populations in the North are solitary, while populations in the south often show sociality, as they face a longer and warmer growing season, leading to the opportunity for two generations in a single year, a pre-condition for the presence of workers provisioning for the (second) brood. Using scanning electron microscope imaging, the authors compared the density of antennal sensilla types in these different populations (north, mid-latitude, south) to test for an association between sociality and olfactory perception capacities. They counted three distinct types of antennal sensilla: olfactory plates, olfactory hairs, and thermos/hygro-receptive pores, used to detect humidity, temperature and CO2. In addition, they took advantage of facultative sociality in this species by transplanting individuals from a northern population (solitary) to a southern location (where conditions favour sociality), to study how social plasticity is reflected (or not) in the density of antennal sensilla types. They tested the prediction that olfactory sensilla density is also developmentally plastic in this species. Their results show that antennal sensilla counts differ between the 3 studied regions (north, mid-latitude, south), but not as predicted. Individuals in the southern population were not significantly different from the mid-latitude and northern ones in their count of olfactory plates and they had less, not more, thermos/hygro receptors than mid-latitude and northern individuals. Furthermore, mid-latitude individuals had more olfactory hairs than the ones from the northern population and did not differ from southern ones. The prediction was that the individuals expressing sociality would have the highest count of these olfactory hairs. This unpredicted pattern based on the latitude of sampling sites may be due to the effect of temperature during development, which was higher in the mid-latitude site than in the southern one. It could also be the result of a genotype-by-environment interaction, where the mid-latitude population has a different developmental response to temperature compared to the other populations, a difference that is genetically determined (a different “reaction norm”). Reciprocal transplant experiments coupled with temperature measurements directly on site would provide interesting information to help further dissect this intriguing pattern. Interestingly, where a sweat bee developed had a significant effect on their antennal sensilla counts: individuals originating from the North that developed in the south after transplantation had significantly more olfactory hairs on their antenna than individuals from the same Northern population that developed in the North. This is in accordance with the prediction that the characteristics of sensory organs can also be plastic. However, there was no difference in antennal characteristics depending on whether these transplanted bees became solitary or expressed the social phenotype (foundress or worker). This result further supports the hypothesis that temperature affects development in this species and that these sensory characteristics are also plastic, although independently of sociality. Overall, the work of Boulton and Field underscores the importance of including phenotypic plasticity in the study of the evolution of social behaviour and provides a robust and fruitful model system to explore this further. References Boulton RA, Field J (2022) Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic bee. bioRxiv, 2022.01.29.478030, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.29.478030 | Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic bee | Rebecca A Boulton, Jeremy Field | <p style="text-align: justify;">The social Hymenoptera have contributed much to our understanding of the evolution of sensory systems. Attention has focussed chiefly on how sociality and sensory systems have evolved together. In the Hymenoptera, t... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Nadia Aubin-Horth | 2022-02-02 11:34:49 | View | |

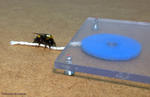

18 Jan 2017

POSTPRINT

Associative Mechanisms Allow for Social Learning and Cultural Transmission of String Pulling in an InsectAlem S, Perry CJ, Zhu X, Loukola OJ, Ingraham T, Søvik E, Chittka L https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002564Culture in BumblebeesRecommended by Caroline Nieberding and Jacques J. M. van AlphenThis is an original paper [1] addressing the question whether cultural transmission occurs in insects and studying the mechanisms of such transmission. Often, culture-like phenomena require relatively sophisticated learning mechanisms, for example imitation and/or teaching. In insects, seemingly complex processes of social information acquisition, can sometimes instead be mediated by relatively simple learning mechanisms suggesting that cultural processes may not necessarily require sophisticated learning abilities. An important quality of this paper is to describe neatly the experimental protocols used for such typically complex behavioural analyses, providing a detailed understanding of the results while it remains a joy to read. This becomes rare in high impact journals. In a clever experimental design, individual bumblebees are trained to pull an artificial flower from under a Plexiglas table to get access to a reward, by pulling a string attached to the flower. Individuals that have learnt this task are then shown to inexperienced bees while performing this task. This results in a large proportion of the inexperienced observers learning to pull the string and getting access to the reward. Finally, the authors could then document the spread of the string pulling skill amongst other workers in the colony. Even when the originally trained individuals had died, the skill of string-pulling persisted in the colony, as long as they were challenged with the task. This shows that cultural transmission takes place within a colony. The authors provide evidence that the transmission of this behavior among individuals relies on a mix of social learning by local enhancement (bees were attracted to the location where they had observed a demonstrator) and of non-social, individual learning (pulling the string is learned by trial and errors and not by direct imitation of the conspecific). Data also show that simple associative mechanisms are enough and that stimulus enhancement was involved (bees were attracted to the string when its location was concordant with that during prior observation). The cleverly designed experiments use a paradigm (string-pulling) which has often been used to investigate cognitive abilities in vertebrates. Comparison with such studies indicate that bees, in some aspects of their learning, may not be different from birds, dogs, or apes as they also relied on the perceptual feedback provided by their actions, resulting in target movement to learn string pulling. The results of the study suggest that the combination of relatively simple forms of social learning and trial-and-error learning can mediate the acquisition of new skills and that bumblebees possess the essential cognitive elements for cultural transmission and in a broader sense, that the capacity of culture may be present within most animals. Can we expect behavioural innovation such as string pulling to occur in nature? Bombus terrestris colonies can reach a total of several hundreds foragers. In the experiments, foragers needed on average 5 rounds of observations with different demonstrators to learn how to pull the string. As individuals forage in a meadow full of flowers and conspecifics, transmission of behavioural innovations by repeated observations shouldn’t strike us as something impossible. Would the behavior survive through the winter? Bumblebee colonies are seasonal in northern areas and in the Mediterranean area but tropical species persists for several years. In seasonal species, all the workers die before winter and only new queens overwinter. So there is no possibility for seasonal foragers to transmit the technique overwinter. Only queens could potentially transmit it to new foragers in spring. However flowers are different in autumn and spring. Therefore, what queens have learnt about flowers in autumn would unlikely be useful in spring (providing that they can remember it). However there is no reason why the technique couldn't be transmitted from a colony to another between spring to autumn. Such transmission of new behaviour would more easily persist in perennial social insect colonies, like honeybees. Importantly, the bees used in these experiments came from a company whose rearing conditions are unknown, and only a few colonies were used for each experiment. As learning ability has a genetic basis [2-3], colonies differ in their ability to learn [4]. In this regard, the authors showed variation between individual bumblebees and between bumblebee colonies in learning ability. Hence, we would wish to know more about the level of genetic diversity in the wild, and of genetic differentiation between tested colonies (were they independent replicates?), to extrapolate the results to what may happen in the wild. Excitingly, the authors found 2 true innovators among the >400 individuals that were tested at least once for 5 min who would solve such a task without stepwise training or observation of skilled demonstrators, showing that behavioural innovation can occur in very small numbers of individuals, provided that an ecological trigger is provided (food reward). Hence this study shows that all ingredients for the long proposed “social heredity” theory proposed by Baldwin in 1896 are available in this organism, suggesting that social transmission of behavioural innovations could technically act as an additional mechanism for adaptive evolution [5], next to genetic evolution that may take longer to produce adaptive evolution. The question remains whether the behavioural innovations are arising from standing genetic variation in the bees, or do not need a firm genetic background to appear. References [1] Alem S, Perry CJ, Zhu X, Loukola OJ, Ingraham T, Søvik E, Chittka L. 2016. Associative mechanisms allow for social learning and cultural transmission of string pulling in an insect. PloS Biology 14:e1002564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002564 [2] Mery F, Kawecki TJ. 2002. Experimental evolution of learning ability in fruit flies. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 99:14274-14279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222371199 [3] Mery F, Belay AT, So AKC, Sokolowski MB, Kawecki TJ. 2007. Natural polymorphism affecting learning and memory in Drosophila. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 104:13051-13055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702923104 [4] Raine NE, Chittka L. 2008. The correlation of learning speed and natural foraging success in bumble-bees. Proceeding of the Royal Society of London 275: 803-808. doi : 10.1098/rspb.2007.1652 [5] Baldwin JM. 1896. A New Factor in Evolution. American Naturalist 30:441-451 and 536-553. doi: 10.1086/276408 | Associative Mechanisms Allow for Social Learning and Cultural Transmission of String Pulling in an Insect | Alem S, Perry CJ, Zhu X, Loukola OJ, Ingraham T, Søvik E, Chittka L | Social insects make elaborate use of simple mechanisms to achieve seemingly complex behavior and may thus provide a unique resource to discover the basic cognitive elements required for culture, i.e., group-specific behaviors that spread from “inn... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Non Genetic Inheritance, Phenotypic Plasticity | Caroline Nieberding | 2017-01-18 10:49:03 | View | |

31 Jul 2017

Selection on morphological traits and fluctuating asymmetry by a fungal parasite in the yellow dung flyWolf U. Blanckenhorn 10.1101/136325Parasite-mediated selection promotes small body size in yellow dung fliesRecommended by Rodrigo Medel based on reviews by Rodrigo Medel and 1 anonymous reviewerBody size has long been considered as one of the most important organismic traits influencing demographical processes, population size, and evolution of life history strategies [1, 2]. While many studies have reported a selective advantage of large body size, the forces that determine small-sized organisms are less known, and reports of negative selection coefficients on body size are almost absent at present. This lack of knowledge is unfortunate as climate change and energy demands in stressful environments, among other factors, may produce new selection scenarios and unexpected selection surfaces [3]. In this manuscript, Blanckenhorn [4] reports on a potential explanation for the surprising 10% body size decrease observed in a Swiss population of yellow dung flies during 1993 - 2009. The author took advantage of a fungus outbreak in 2002 to assess the putative role of the fungus Entomopthora scatophagae, a specific parasite of adult yellow dung flies, as selective force acting upon host body size. His findings indicate that, as expected by sexual selection theory, large males experience a mating advantage. However, this positive sexual selection is opposed by a strong negative selection on male and female body size through the viability fitness component. This study provides the first evidence of parasite-mediated disadvantage of large adult body size in the field. While further experimental work is needed to elucidate the exact causes of body size reduction in the population, the author proposes a variation of the trade-off hypothesis raised by Rantala & Roff [5] that large-sized individuals face an immunity cost due to their high absolute energy demands in stressful environments. References [1] Peters RH. 1983. The ecological implications of body size. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [2] Schmidt-Nielsen K. 1984. Scaling: why is animal size so important? Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [3] Ohlberger J. 2013. Climate warming and ectotherm body size: from individual physiology to community ecology. Functional Ecology 27: 991-1001. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12098 [4] Blanckenhorn WU. 2017. Selection on morphological traits and fluctuating asymmetry by a fungal parasite in the yellow dung fly. bioRxiv 136325, ver. 2 of 29th June 2017. doi: 10.1101/136325 [5] Rantala MJ & Roff DA. 2005. An analysis of trade-offs in immune function, body size and development time in the Mediterranean field cricket, Gryllus bimaculatus. Functional Ecology 19: 323-330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2005.00979.x | Selection on morphological traits and fluctuating asymmetry by a fungal parasite in the yellow dung fly | Wolf U. Blanckenhorn | Evidence for selective disadvantages of large body size remains scarce in general. Previous phenomenological studies of the yellow dung fly *Scathophaga stercoraria* have demonstrated strong positive sexual and fecundity selection on male and fema... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Sexual Selection | Rodrigo Medel | Rodrigo Medel | 2017-05-10 11:16:26 | View |

25 Feb 2021

Alteration of gut microbiota with a broad-spectrum antibiotic does not impair maternal care in the European earwigSophie Van Meyel, Séverine Devers, Simon Dupont, Franck Dedeine and Joël Meunier https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.08.331363Assessing the role of host-symbiont interactions in maternal care behaviourRecommended by Trine Bilde based on reviews by Nadia Aubin-Horth, Gabrielle Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nadia Aubin-Horth, Gabrielle Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer

The role of microbial symbionts in governing social traits of their hosts is an exciting and developing research area. Just like symbionts influence host reproductive behaviour and can cause mating incompatibilities to promote symbiont transmission through host populations (Engelstadter and Hurst 2009; Correa and Ballard 2016; Johnson and Foster 2018) (see also discussion on conflict resolution in Johnsen and Foster 2018), microbial symbionts could enhance transmission by promoting the social behaviour of their hosts (Ezenwa et al. 2012; Lewin-Epstein et al. 2017; Gurevich et al. 2020). Here I apply the term ‘symbiosis’ in the broad sense, following De Bary 1879 as “the living together of two differently named organisms“ independent of effects on the organisms involved (De Bary 1879), i.e. the biological interaction between the host and its symbionts may include mutualism, parasitism and commensalism. References Correa, C. C., and Ballard, J. W. O. (2016). Wolbachia associations with insects: winning or losing against a master manipulator. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 3, 153. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2015.00153 De Bary, A. (1879). Die Erscheinung der Symbiose. Verlag von Karl J. Trubner, Strassburg. Engelstädter, J., and Hurst, G. D. (2009). The ecology and evolution of microbes that manipulate host reproduction. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 40, 127-149. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120206 Ezenwa, V. O., Gerardo, N. M., Inouye, D. W., Medina, M., and Xavier, J. B. (2012). Animal behavior and the microbiome. Science, 338(6104), 198-199. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1227412 Gurevich, Y., Lewin-Epstein, O., and Hadany, L. (2020). The evolution of paternal care: a role for microbes?. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 375(1808), 20190599. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0599 Hird, S. M. (2017). Evolutionary biology needs wild microbiomes. Frontiers in microbiology, 8, 725. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00725 Johnson, K. V. A., and Foster, K. R. (2018). Why does the microbiome affect behaviour?. Nature reviews microbiology, 16(10), 647-655. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0014-3 Kramer et al. (2017). When earwig mothers do not care to share: parent–offspring competition and the evolution of family life. Functional Ecology, 31(11), 2098-2107. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12915 Lewin-Epstein, O., Aharonov, R., and Hadany, L. (2017). Microbes can help explain the evolution of host altruism. Nature communications, 8(1), 1-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14040 Meunier, J., and Kölliker, M. (2012). Parental antagonism and parent–offspring co-adaptation interact to shape family life. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279(1744), 3981-3988. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.1416 Meunier, J., Wong, J. W., Gómez, Y., Kuttler, S., Röllin, L., Stucki, D., and Kölliker, M. (2012). One clutch or two clutches? Fitness correlates of coexisting alternative female life-histories in the European earwig. Evolutionary Ecology, 26(3), 669-682. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-011-9510-x Nalepa, C. A. (2020). Origin of mutualism between termites and flagellated gut protists: transition from horizontal to vertical transmission. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 8, 14. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00014 Ratz, T., Kramer, J., Veuille, M., and Meunier, J. (2016). The population determines whether and how life-history traits vary between reproductive events in an insect with maternal care. Oecologia, 182(2), 443-452. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-016-3685-3 Van Meyel, S., Devers, S., Dupont, S., Dedeine, F. and Meunier, J. (2021) Alteration of gut microbiota with a broad-spectrum antibiotic does not impair maternal care in the European earwig. bioRxiv, 2020.10.08.331363. ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.08.331363 | Alteration of gut microbiota with a broad-spectrum antibiotic does not impair maternal care in the European earwig | Sophie Van Meyel, Séverine Devers, Simon Dupont, Franck Dedeine and Joël Meunier | <p>The microbes residing within the gut of an animal host often increase their own fitness by modifying their host’s physiological, reproductive, and behavioural functions. Whereas recent studies suggest that they may also shape host sociality and... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Life History, Species interactions | Trine Bilde | 2020-10-09 14:07:47 | View | |

29 Nov 2023

Does sociality affect evolutionary speed?Lluís Socias-Martínez, Louise Rachel Peckre https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10086186On the evolutionary implications of being a social animalRecommended by Michael D Greenfield based on reviews by Rafael Lucas Rodriguez and 1 anonymous reviewerWhat does it mean to be highly social? Considering the so-called four ‘pinnacles’ of animal society (Wilson, 1975) – humans, cooperative breeding as found in some non-human mammals and birds, the social insects, and colonial marine invertebrates – having inter-individual relations extending beyond the sexual pair and the parent-offspring interaction is foremost. In many cases being social implies a high local population density, interaction with the same group of individuals over an extended time period, and an overlapping of generations. Additional features of social species may be a wide geographical range, perhaps associated with ecological and behavioral plasticity, the latter often facilitated by cultural transmission of traditions. Narrowing our perspective to the domain of PCI Evolutionary Biology, we might continue our question by asking whether being social predisposes one to a special evolutionary path toward the future. Do social species evolve faster (or slower) than their more solitary relatives such that over time they are more unlike (or similar to) those relatives (anagenesis)? And are evolutionary changes in social species more or less likely to be accompanied by lineage splitting (cladogenesis) and ultimately speciation? The latter question is parallel to one first posed over 40 years ago (West-Eberhard, 1979; Lande, 1981) for sexually selected traits: Do strong mating preferences and conspicuous courtship signals generate speciation via the Fisherian process or ecological divergence? An extensive survey of birds had found little supporting evidence (Price, 1998), but a recent one that focused on plumage complexity in tanagers did reveal a relationship, albeit a weak one (Price-Waldman et al., 2020). Because sexual selection has been viewed as a part of the broader process of social selection (West-Eberhard, 1979), it is thus fitting to extend our surveys to the evolutionary implications of being social. Unlike the inquiry for a sexual selection - evolutionary change connection, a social behavior counterpart has remained relatively untreated. Diverse logistical problems might account for this oversight. What objective proxies can be used for social behavior, and for the rate of evolutionary change within a lineage? How many empirical studies have generated data from which appropriate proxies could be extracted? More intractable is the conundrum arising from the connectedness between socially- and sexually-selected traits. For example, the elevated population density found in highly social species can greatly increase the mating advantage enjoyed by an attractive male. If anagenesis is detected, did it result from social behavior or sexual selection? And if social behavior leads to a group structure in which male-male competition is reduced, would a modest rate of evolutionary change be support for the sexual selection - evolutionary speed connection or evidence opposing the sociality - evolution one? Against the above odds, several biologists have begun to explore the notion that social behavior just might favor evolutionary speed in either anagenesis or cladogenesis. In a recent analysis relying on the comparative method, Lluís Socias-Martínez and Louise Rachel Peckre (2023) combed the scientific literature archives and identified those studies with specific data on the relationships between sexual selection or social behavior and evolutionary change, either anagenesis or cladogenesis. The authors were careful to employ fairly conservative criteria for including studies, and the number eventually retained was small. Nonetheless, some patterns emerge: Many more studies report anagenesis than cladogenesis, and many more report correlations with sexually-selected traits than with non-sexual social behavior ones. And, no study indicates a potential effect of social behavior on cladogenesis. Is this latter observation authentic or an artifact of a paucity of data? There are some a priori reasons why cladogenesis may seldom arise. Whereas highly social behavior could lead to fission encompassing mutually isolated population clusters within a species, social behavior may also engender counterbalancing plasticity that allows and even promotes inter-cluster migration and fusion. And briefly – and non-systematically, as the rate of lineage splitting would need to be measured – looking at one of the pinnacles of animal social behavior, the social insects, there is little indication that diversification has been accelerated. There are fewer than 3000 described species of termites, only ca. 16,000 ants, and the vast majority of bees and wasps are solitary. Lluís Socias-Martínez and Louise Rachel Peckre provide us with a very detailed discussion of these and a myriad of other complications. I end with a common refrain, we need more consideration of the authors’ interesting question, and much more data and analysis. One can thank Socias-Martínez and Peckre for pointing us in that direction. References Lande, R. (1981). Models of speciation by sexual selection on polygenic traits. Proc. Natn. Acad. Sci. USA 78, 3721-3725. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.78.6.3721 Price, T. (1998). Sexual selection and natural selection in bird speciation. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. B, 353, 251-260. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1998.0207 Price‐Waldman, R. M., Shultz, A. J., & Burns, K. J. (2020). Speciation rates are correlated with changes in plumage color complexity in the largest family of songbirds. Evolution, 74(6), 1155–1169. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13982 Socias-Martínez and Peckre. (2023). Does sociality affect evolutionary speed? Zenodo, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10086186 West-Eberhard, M. J. (1979). Sexual selection, social competition, and evolution. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 123(4), 222–234. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2828804 Wilson, E. O. (1975). Sociobiology. The New Synthesis. Cambridge, Mass., The Belknap Press of Harvard University | Does sociality affect evolutionary speed? | Lluís Socias-Martínez, Louise Rachel Peckre | <p>An overlooked source of variation in evolvability resides in the social lives of animals. In trying to foster research in this direction, we offer a critical review of previous work on the link between evolutionary speed and sociality. A first ... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Sexual Selection, Speciation | Michael D Greenfield | 2023-03-03 00:10:49 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer