Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▼ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

10 Jan 2020

Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shiftsGilles Didier https://doi.org/10.1101/376756Fitting diversification models on undated or partially dated treesRecommended by Nicolas Lartillot based on reviews by Amaury Lambert, Dominik Schrempf and 1 anonymous reviewerPhylogenetic trees can be used to extract information about the process of diversification that has generated them. The most common approach to conduct this inference is to rely on a likelihood, defined here as the probability of generating a dated tree T given a diversification model (e.g. a birth-death model), and then use standard maximum likelihood. This idea has been explored extensively in the context of the so-called diversification studies, with many variants for the models and for the questions being asked (diversification rates shifting at certain time points or in the ancestors of particular subclades, trait-dependent diversification rates, etc). References [1] Didier, G. (2020) Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shifts. bioRxiv, 376756, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/376756 | Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shifts | Gilles Didier | <p>Dating the tree of life is a task far more complicated than only determining the evolutionary relationships between species. It is therefore of interest to develop approaches apt to deal with undated phylogenetic trees. The main result of this ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Macroevolution | Nicolas Lartillot | 2019-01-30 11:28:58 | View | |

08 Feb 2019

Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenesAnouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo https://doi.org/10.1101/337477E5, the third oncogene of PapillomavirusRecommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Leonardo de Oliveira Martins and 1 anonymous reviewerPapillomaviruses (PVs) infect almost all mammals and possibly amniotes and bony fishes. While most of them have no significant effects on the hosts, some induce physical lesions. Phylogeny of PVs consists of a few crown groups [1], among which AlphaPVs that infect primates including human have been well studied. They are associated to largely different clinical manifestations: non-oncogenic PVs causing anogenital warts, oncogenic and non-oncogenic PVs causing mucosal lesions, and non-oncogenic PVs causing cutaneous warts. References [1] Bravo, I. G., & Alonso, Á. (2004). Mucosal human papillomaviruses encode four different E5 proteins whose chemistry and phylogeny correlate with malignant or benign growth. Journal of virology, 78, 13613-13626. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13613-13626.2004 | Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenes | Anouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo | <p>The clinical presentations of papillomavirus (PV) infections come in many different flavors. While most PVs are part of a healthy skin microbiota and are not associated to physical lesions, other PVs cause benign lesions, and only a handful of ... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Hirohisa Kishino | 2018-06-04 16:15:39 | View | |

13 Jan 2019

Why cooperation is not running awayFélix Geoffroy, Nicolas Baumard, Jean-Baptiste André https://doi.org/10.1101/316117A nice twist on partner choice theoryRecommended by Erol Akcay based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersIn this paper, Geoffroy et al. [1] deal with partner choice as a mechanism of maintaining cooperation, and argues that rather than being unequivocally a force towards improved payoffs to everyone through cooperation, partner choice can lead to “over-cooperation” where individuals can evolve to invest so much in cooperation that the costs of cooperating partially or fully negate the benefits from it. This happens when partner choice is consequential and effective, i.e., when interactions are long (so each decision to accept or reject a partner is a bigger stake) and when meeting new partners is frequent when unpaired (so that when one leaves an interaction one can find a new partner quickly). Geoffroy et al. [1] show that this tendency to select for overcooperation under such regimes can be counteracted if individuals base their acceptance-rejection of partners not just on the partner cooperativeness, but also on their own. By using tools from matching theory in economics, they show that plastic partner choice generates positive assortment between cooperativeness of the partners, and in the extreme case of perfectly assortative pairings, makes the pair the unit of selection, which selects for maximum total payoff. References [1] Geoffroy, F., Baumard, N., & Andre, J.-B. (2019). Why cooperation is not running away. bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/316117 | Why cooperation is not running away | Félix Geoffroy, Nicolas Baumard, Jean-Baptiste André | <p>A growing number of experimental and theoretical studies show the importance of partner choice as a mechanism to promote the evolution of cooperation, especially in humans. In this paper, we focus on the question of the precise quantitative lev... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Theory | Erol Akcay | 2018-05-15 10:32:51 | View | |

08 Nov 2021

Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression over development in the stick insect Timema californicumJelisaveta Djordjevic, Zoé Dumas, Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Tanja Schwander, Darren James Parker https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.23.427895Sex-biased gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect: pattern during development, extent, functions involved, rate of sequence evolution, and comparison with an holometabolous insectRecommended by Nadia Aubin-Horth based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersAn individual’s sexual phenotype is determined during development. Understanding which pathways are activated or repressed during the developmental stages leading to a sexually mature individual, for example by studying gene expression and how its level is biased between sexes, allows us to understand the functional aspects of dimorphic phenotypes between the sexes. Several studies have quantified the differences in transcription between the sexes in mature individuals, showing the extent of this sex-bias and which functions are affected. There is, however, less data available on what occurs during the different phases of development leading to this phenotype, especially in species with specific developmental strategies, such as hemimetabolous insects. While many well-studied insects such as the honey bee, drosophila, and butterflies, exhibit an holometabolous development ("holo" meaning "complete" in reference to their drastic metamorphosis from the juvenile to the adult stage), hemimetabolous insects have juvenile stages that look similar to the adult stage (the hemi prefix meaning "half", referring to the more tissue-specific changes during development), as seen in crickets, cockroaches, and stick insects. Learning more about what happens during development in terms of the identity of genes that are sex-biased (are they the same genes at different developmental stages? What are their function? Do they exhibit specific sequence evolution rates? Is one sex over-represented in the sex-biased genes?) and their quantity over developmental time (gradual or abrupt increase in number, if any?) would allow us to better understand the evolution of sexual dimorphism at the gene expression level and how it relates to dimorphism at the organismic level. Djordjevic et al (2021) studied the transcriptome during development in an hemimetabolous stick insect, to improve our knowledge of this type of development, where the organismic phenotype is already mostly present in the early life stages. To do this, they quantified whole-genome gene expression levels in whole insects, using RNA-seq at three different developmental stages. One of the interesting results presented by Djordjevic and colleagues is that the increase in the number of genes that were sex-biased in expression is gradual over the three stages of development studied and it is mostly the same genes that stay sex-biased over time, reflecting the gradual change in phenotypes between hatchlings, juveniles and adults. Furthermore, male-biased genes had faster sequence divergence rates than unbiased genes and that female-biased genes. This new information of sex-bias in gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect allowed the authors to do a comparison of sex-biased genes with what has been found in a well-studied holometabolous insect, Drosophila. The gene expression patterns showed that four times more genes were sex-biased in expression in that species than in stick insects. Furthermore, the increase in the number of sex-biased genes during development was quite abrupt and clearly distinct in the adult stage, a pattern that was not seen in stick insects. As pointed out by the authors, this pattern of a "burst" of sex-biased genes at maturity is more common than the gradual increase seen in stick insects. With this study, we now know more about the evolution of sex-biased gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect and how it relates to their phenotypic dimorphism. Clearly, the next step will be to sample more hemimetabolous species at different life stages, to see how this pattern is widespread or not in this mode of development in insects. References Djordjevic J, Dumas Z, Robinson-Rechavi M, Schwander T, Parker DJ (2021) Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression during development in the stick insect Timema californicum. bioRxiv, 2021.01.23.427895, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.23.427895 | Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression over development in the stick insect Timema californicum | Jelisaveta Djordjevic, Zoé Dumas, Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Tanja Schwander, Darren James Parker | <p style="text-align: justify;">Sexually dimorphic phenotypes are thought to arise primarily from sex-biased gene expression during development. Major changes in developmental strategies, such as the shift from hemimetabolous to holometabolous dev... |  | Evo-Devo, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Nadia Aubin-Horth | 2021-04-22 17:36:32 | View | |

19 Feb 2018

Genomic imprinting mediates dosage compensation in a young plant XY systemAline Muyle, Niklaus Zemp, Cecile Fruchard, Radim Cegan, Jan Vrana, Clothilde Deschamps, Raquel Tavares, Franck Picard, Roman Hobza, Alex Widmer, Gabriel Marais https://doi.org/10.1101/179044Dosage compensation by upregulation of maternal X alleles in both males and females in young plant sex chromosomesRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Judith Mank based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersSex chromosomes evolve as recombination is suppressed between the X and Y chromosomes. The loss of recombination on the sex-limited chromosome (the Y in mammals) leads to degeneration of both gene expression and gene content for many genes [1]. Loss of gene expression or content from the Y chromosome leads to differences in gene dose between males and females for X-linked genes. Because expression levels are often correlated with gene dose [2], these hemizygous genes have a lower expression levels in the heterogametic sex. This in turn disrupts the stoichiometric balance among genes in protein complexes that have components on both the sex chromosomes and autosomes [3], which could have serious deleterious consequences for the heterogametic sex. References | Genomic imprinting mediates dosage compensation in a young plant XY system | Aline Muyle, Niklaus Zemp, Cecile Fruchard, Radim Cegan, Jan Vrana, Clothilde Deschamps, Raquel Tavares, Franck Picard, Roman Hobza, Alex Widmer, Gabriel Marais | <p>During the evolution of sex chromosomes, the Y degenerates and its expression gets reduced relative to the X and autosomes. Various dosage compensation mechanisms that recover ancestral expression levels in males have been described in animals.... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Expression Studies, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Tatiana Giraud | 2017-09-20 20:39:46 | View | |

22 Feb 2023

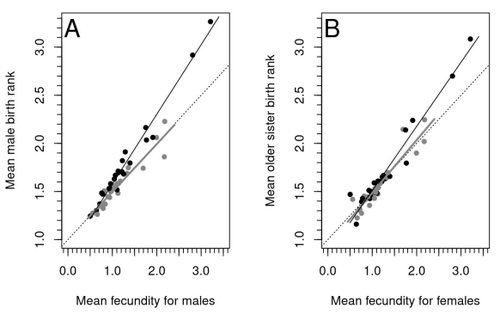

Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesisMichel Raymond, Daniel Turek, Valerie Durand, Sarah Nila, Bambang Suryobroto, Julien Vadez, Julien Barthes, Menelaos Apostolou, Pierre-André Crochet https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.22.481477Evolutionary or proximal explanations for human male homosexual mate preference?Recommended by Jacqui A. Shykoff based on reviews by Ray Blanchard and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Ray Blanchard and 1 anonymous reviewer

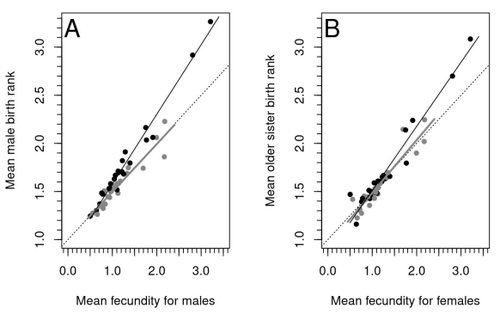

Natural populations do not consist of only perfectly adapted individuals. If they did, of course, there would be no fodder for evolution by natural selection. And natural selection is operating all the time, winnowing out less well adapted phenotypes through differential reproduction and survival. Demonstrations of natural selection modifying characters-state distributions to bring phenotypes closer to their optima abound in the evolution literature, with examples of short- and long-term changes in phenotype and allele frequencies. However, evolutionary biologists know that populations cannot reach their adaptive peaks. Natural selection is tracking a moving target, always with some generations of lag time. The adaptive landscape is multidimensional, so the optimal combination of multiple character states may be impossible because of constraints and trade-offs. Natural selection does not operate alone or in isolation – new mutations and migrants that were selected under other conditions will inject locally non-adaptive genetic variation and genetic drift can change allele frequencies in random directions. We understand these processes that generate and maintain less advantageous variants on a continuous gradient from an optimal phenotype in a fitness landscape. More puzzling are heritable polymorphisms with distinct morphologies, physiologies or behaviours maintained in populations despite their measurably lower reproductive success. But a complete model of evolution must also be able to accommodate these Darwinian paradoxes. Raymond et al. (2023) investigate one such Darwinian paradox: In humans, male homosexual mate preference is heritable and is associated with a large reduction in offspring production but nonetheless occurs at relatively high frequencies in most human populations. Furthermore, multiple studies have found that homosexual men come from families that are, on average, larger than those of heterosexual men and that homosexual men have, on average, higher birth rank than do heterosexual men, i.e., having more older siblings and, particularly, more older brothers. Two types of mechanisms consistent with these observations have been proposed: 1) An evolutionary mechanism of sex-antagonistic pleiotropy, whereby highly fecund mothers are more likely to produce homosexual sons, and 2) A mechanistic explanation whereby successive male pregnancies alter the uterine environment by increasing the probability of an immune reaction by the mother to her male fetus, altering development of sexually dimorphic brain structures relevant to sexual orientation. In this article, the authors explore these two mechanisms of sex-antagonistic effects (AE) and fraternal birth order effects (FBOE) and test how well they account for patterns of male homosexuality in population and family data. Clearly, these two effects are somewhat confounded because high birth ranks can only occur in large families. If, indeed, the probability of male homosexuality increases with increasing numbers of (maternal) older brothers, homosexual males will be more common in larger families. Similarly, if high female fecundity leads to a higher probability of male homosexuality via sex-antagonistic effects, homosexual males will, on average, have more older brothers. To disentangle the actions of these two effects the authors modelled the relationship between birth rank and population fecundity and investigated whether AE or FBOE modified this relationship for homosexual men. Simulation results were compared with aggregated population data from 13 countries. Family data on individuals’ sexual preference, birth rank and number of male and female siblings from France, Greece and Indonesia were analysed with generalised linear models and Bayesian approaches to test for a signal of AE or FBOE. These analyses revealed a significant older-brother effect (FBOE) explaining patterns of occurrence of homosexuality in population and family data but no significant independent sex-antagonistic effect (AE). Thus larger family sizes of homosexual men appear due to the older-brother effect, with individuals of high birth rank coming necessarily from large sibships. The simulation approach also revealed that modelling a fraternal birth order effect (FBOE), such that individuals with more older brothers are more likely to be homosexual, generates an artefactual older sister effect simply because homosexual men are overrepresented at higher birth ranks. Older-sister effects reported in the literature may, therefore, be statistical artefacts of an underlying older-brother effect. This paper is interesting for a number of reasons. It does an excellent job of explaining, identifying and dealing with estimation biases and testing for artefactual relationships generated by collinearity. It applies state-of-the art analytical/statistical tools. It breaks down two colinear effects and shows that only one really explains phenotypic variation. This is a great example of how to disentangle correlated variables that may or may not both contribute to trait variation. But most intriguingly, we are left without evidence for an evolutionary mechanism that compensates the large fitness cost associated with male homosexuality in humans. How can we explain high heritability maintained in the face of strong directional selection that should erode heritable genetic variation? The usual suspects include cryptic compensatory mechanisms yet to be discovered or flawed estimates of selection or heritability. For example, data on heritability of male homosexual mate preference in humans come from twin studies and twins share birth rank as well as alleles. Thus it is possible that heritability is over-estimated, including the environmental component associated with birth rank. If, as the authors demonstrate here, birth rank is the strongest predictor of male homosexual mate preference, selection may be acting on a non-heritable plastic component of phenotypic variation. This could explain why heritable variation is not exhausted by selection, rendering the paradox less paradoxical, but fails to provide an adaptive explanation for the maintenance of male homosexual mate preference. References Raymond M., Turek D., Durand V., Nila S., Suryobroto B., Vadez J., Barthes J., Apostolou M. and Crochet P.-A. (2023) Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesis. bioRxiv, 2022.02.22.481477, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.22.481477 | Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesis | Michel Raymond, Daniel Turek, Valerie Durand, Sarah Nila, Bambang Suryobroto, Julien Vadez, Julien Barthes, Menelaos Apostolou, Pierre-André Crochet | <p style="text-align: justify;">Male homosexual orientation remains a Darwinian paradox, as there is no consensus on its evolutionary (ultimate) determinants. One intriguing feature of homosexual men is their higher male birth rank compared to het... |  | Life History, Other, Phenotypic Plasticity, Reproduction and Sex | Jacqui A. Shykoff | 2022-03-03 11:28:44 | View | |

15 Sep 2022

Bimodal breeding phenology in the Parsley Frog Pelodytes punctatus as a bet-hedging strategy in an unpredictable environment despite strong priority effectsHelene Jourdan-Pineau, Pierre-Andre Crochet, Patrice David https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.24.481784Spreading the risk of reproductive failure when the environment is unpredictable and ephemeralRecommended by Gabriele Sorci based on reviews by Thomas Haaland and Zoltan RadaiMany species breed in environments that are unpredictable, for instance in terms of the availability of resources needed to raise the offspring. Organisms might respond to such spatial and temporal unpredictability by adopting plastic responses to adjust their reproductive investment according to perceived cues of environmental quality. Some species such as the amphibians might also face the problem of ephemeral habitats, when the ponds where they breed have a chance of drying up before metamorphosis has occurred. In this case, maximizing long-term fitness might involve a strategy of spreading the risk, even though the reproductive success of a single reproductive bout might be lower. Understanding how animals (and plants) get adapted to stochastic environments is particularly crucial in the current context of rapid environmental changes. In this article, Jourdan-Pineau et al. report the results of field surveys of the Parsley Frog (Pelodytes punctatus) in Southern France. This frog has peculiar breeding phenology with females breeding in autumn and spring. The authors provide quite an extensive amount of information on the reproductive success of eggs laid in each season and the possible ecological factors accounting for differences between seasons. Although the presence of interspecific competitors and predators does not seem to account for pond-specific reproductive success, the survival of tadpoles hatching from eggs laid in spring is severely impaired when tadpoles from the autumn cohort have managed to survive. This intraspecific competition takes the form of a “priority” effect where tadpoles from the autumn cohort outcompete the smaller larvae from the spring cohort. Given this strong priority effect, one might tentatively predict that females laying in spring should avoid ponds with tadpoles from the autumn cohort. Surprisingly, however, the authors did not find any evidence for such avoidance, which might indicate strong constraints on the availability of ponds where females might possibly lay. Assuming that each female can indeed lay both in autumn and spring, how is this bimodal phenology maintained? Would not be worthier to allocate all the eggs to the autumn (or the spring) laying season? Eggs laid in autumn and spring have to face different environmental hazards, reducing their hatching success and the probability to produce metamorphs (for instance, tadpoles hatching from eggs laid in autumn have to overwinter which might be a particularly risky phase). Jourdan-Pineau and coworkers addressed this question by adapting a bet-hedging model that was initially developed to investigate the strategy of allocation into seed dormancy of annual plants (Cohen 1966) to the case of the bimodal phenology of the Parsley Frog. By feeding the model with the parameter values obtained from the field surveys, they found that the two breeding strategies (laying in autumn and in spring) can coexist as long as the probability of breeding success in the autumn cohort is between 20% and 80% (the range of values allowing the coexistence of a bimodal phenology shrinking a little bit when considering that frogs can reproduce 5 times during their lifespan instead of three times). This paper provides a very nice illustration of the importance of combining approaches (here field monitoring to gather data that can be used to feed models) to understand the evolution of peculiar breeding strategies. Although future work should attempt to gather individual-based data (in addition to population data), this work shows that spreading the risk can be an adaptive strategy in environments characterized by strong stochastic variation. References Cohen D (1966) Optimizing reproduction in a randomly varying environment. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 12, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(66)90188-3 Jourdan-Pineau H., Crochet P.-A., David P. (2022) Bimodal breeding phenology in the Parsley Frog Pelodytes punctatus as a bet-hedging strategy in an unpredictable environment despite strong priority effects. bioRxiv, 2022.02.24.481784, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.24.481784 | Bimodal breeding phenology in the Parsley Frog Pelodytes punctatus as a bet-hedging strategy in an unpredictable environment despite strong priority effects | Helene Jourdan-Pineau, Pierre-Andre Crochet, Patrice David | <p style="text-align: justify;">When environmental conditions are unpredictable, expressing alternative phenotypes spreads the risk of failure, a mixed strategy called bet-hedging. In the southern part of its range, the Parsley Frog <em>Pelodytes ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Gabriele Sorci | 2022-02-28 11:53:00 | View | |

03 Oct 2018

Range size dynamics can explain why evolutionarily age and diversification rate correlate with contemporary extinction risk in plantsAndrew J. Tanentzap, Javier Igea, Matthew G. Johnston, Matthew J. Larcombe https://doi.org/10.1101/152215Are both very young and the very old plant lineages at heightened risk of extinction?Recommended by Arne Mooers based on reviews by Dan Greenberg and 1 anonymous reviewerHuman economic activity is responsible for the vast majority of ongoing extinction, but that does not mean lineages are being affected willy-nilly. For amphibians [1] and South African flowering plants [2], young species have a somewhat higher than expected chance of being threatened with extinction. In contrast, older Australian marsupial lineages seem to be more at risk [3]. Both of the former studies suggested that situations leading to peripheral isolation might simultaneously increase ongoing speciation and current threat via small geographic range, while the authors of the latter study suggested that older species might have evolved increasingly narrow niches. Here, Andrew Tanentzap and colleagues [4] dig deeper into the putative links between species age, niche breadth and threat status. Across 500-some plant genera worldwide, they find that, indeed, ""younger"" species (i.e. from younger and faster-diversifying genera) were more likely to be listed as imperiled by the IUCN, consistent with patterns for amphibians and African plants. Given this, results from their finer-level analyses of conifers are initially bemusing: here, ""older"" (i.e., on longer terminal branches) species were at higher risk. This would make conifers more like Australian marsupials, with the rest of the plants being more like amphibians. However, here where the data were more finely grained, the authors detected a second interesting pattern: using an intriguing matched-pair design, they detect a signal of conifer species niches seemingly shrinking as a function of age. The authors interpret this as consistent with increasing specialization, or loss of ancestral warm wet habitat, over paleontological time. It is true that conifers in general are older than plants more generally, with some species on branches that extend back many 10s of millions of years, and so a general loss of suitable habitat makes some sense. If so, both the pattern for all plants (small initial ranges heightening extinction) and the pattern for conifers (eventual increasing specialization or habitat contraction heightening extinction) could occur, each on a different time scale. As a coda, the authors detected no effect of age on threat status in palms; however, this may be both because palms have already lost species to climate-change induced extinction, and because they are thought to speciate more via long-distance dispersal and adaptive divergence then via peripheral isolation. References [1] Greenberg, D. A., & Mooers, A. Ø. (2017). Linking speciation to extinction: Diversification raises contemporary extinction risk in amphibians. Evolution Letters, 1, 40–48. doi: 10.1002/evl3.4 | Range size dynamics can explain why evolutionarily age and diversification rate correlate with contemporary extinction risk in plants | Andrew J. Tanentzap, Javier Igea, Matthew G. Johnston, Matthew J. Larcombe | <p>Extinction threatens many species, yet few factors predict this risk across the plant Tree of Life (ToL). Taxon age is one factor that may associate with extinction if occupancy of geographic and adaptive zones varies with time, but evidence fo... |  | Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Arne Mooers | 2018-02-01 21:01:19 | View | |

07 Nov 2017

MaxTiC: Fast ranking of a phylogenetic tree by Maximum Time Consistency with lateral gene transfersCédric Chauve, Akbar Rafiey, Adrian A. Davin, Celine Scornavacca, Philippe Veber, Bastien Boussau, Gergely J Szöllosi, Vincent Daubin, and Eric Tannier 10.1101/127548Dating nodes in a phylogeny using inferred horizontal gene transfersRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Toni Gabaldon based on reviews by Alexandros Stamatakis, Mukul Bansal and 2 anonymous reviewersDating nodes in a phylogeny is an important problem in evolution and is typically performed by using molecular clocks and fossil age estimates [1]. The manuscript by Chauve et al. [2] reports a novel method, which uses lateral gene transfers to help ordering nodes in a species tree. The idea is that a lateral gene transfer can only occur between two species living at the same time, which indirectly informs on node relative ages in a phylogeny: the donor species cannot be more recent than the recipient species. Horizontal gene transfers are increasingly recognized as frequent, even in eukaryotes, and especially in micro-organisms that have little fossil records [3-7]. Yet, such an important source of information has been very rarely used so far for inferring relative node ages in phylogenies. In this context, the method by Chauve et al. [2] represents an innovative and original approach to a difficult problem. An obvious limitation of the approach is that it relies on inferences of horizontal transfers, which detection is in itself a difficult problem. Incomplete taxon sampling, or the extinction of the true donor lineage may render patterns difficult to interpret in a temporary fashion. Yet, for clades with no fossils this may be the only piece of information we have at hand, and the growing amount of sequence data is likely to minimize issues derived from incomplete sampling. The developed method, MaxTiC (for Maximal Time Consistency) [2], represents a very nice application of theoretical developments on the well-known « Feedback Arc Set » computer science problem to the evolutionary question of ordering nodes in a phylogeny. MaxTiC uses as input a species tree and a set of time constraints based on lateral gene transfers inferred using other softwares, and minimizes conflicts between node ordering and these time constraints. The application of MaxTiC on simulated datasets indicated that node ordering was fairly accurate [2]. MaxTiC is implemented in a freely available software, which represents original and relevant contribution to the field of evolutionary biology. References [1] Donoghue P and Smith M, editors. 2003. Telling the evolutionary time. CRC press. [2] Chauve C, Rafiey A, Davin AA, Scornavacca C, Veber P, Boussau B, Szöllősi GJ, Daubin V and Tannier E. 2017. MaxTiC: Fast ranking of a phylogenetic tree by Maximum Time Consistency with lateral gene transfers. bioRxiv 127548, ver. 6 of 6th November 2017. doi: 10.1101/127548 [3] Ropars J, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Lopez-Villavicencio M, Gouzy J, Sallet E, Debuchy R, Dupont J, Branca A and Giraud T. 2015. Adaptive horizontal gene transfers between multiple cheese-associated fungi. Current Biology 19, 2562–2569. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.025 [4] Novo M, Bigey F, Beyne E, Galeote V, Gavory F, Mallet S, Cambon B, Legras JL, Wincker P, Casaregola S and Dequin S. 2009. Eukaryote-to-eukaryote gene transfer events revealed by the genome sequence of the wine yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae EC1118. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA, 106, 16333–16338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904673106 [5] Naranjo-Ortíz MA, Brock M, Brunke S, Hube B, Marcet-Houben M, Gabaldón T. 2016. Widespread inter- and intra-domain horizontal gene transfer of d-amino acid metabolism enzymes in Eukaryotes. Frontiers in Microbiology 7, 2001. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02001 [6] Alexander WG, Wisecaver JH, Rokas A, Hittinger CT. 2016. Horizontally acquired genes in early-diverging pathogenic fungi enable the use of host nucleosides and nucleotides. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA. 113, 4116–4121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517242113 [7] Marcet-Houben M, Gabaldón T. 2010. Acquisition of prokaryotic genes by fungal genomes. Trends in Genetics. 26, 5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.11.007 | MaxTiC: Fast ranking of a phylogenetic tree by Maximum Time Consistency with lateral gene transfers | Cédric Chauve, Akbar Rafiey, Adrian A. Davin, Celine Scornavacca, Philippe Veber, Bastien Boussau, Gergely J Szöllosi, Vincent Daubin, and Eric Tannier | Lateral gene transfers (LGTs) between ancient species contain information about the relative timing of species diversification. Specifically, the ancestors of a donor species must have existed before the descendants of the recipient species. Hence... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Genome Evolution, Life History, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Tatiana Giraud | 2017-06-28 13:40:52 | View | |

22 May 2017

Can Ebola Virus evolve to be less virulent in humans?Mircea T. Sofonea, Lafi Aldakak, Luis Fernando Boullosa, Samuel Alizon 10.1101/108589A new hypothesis to explain Ebola's high virulenceRecommended by Virginie Ravigné and François Blanquart based on reviews by Virginie Ravigné and François Blanquart

The tragic 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak that resulted in more than 28,000 cases and 11,000 deaths in West Africa [1] has been a surprise to the scientific community. Before 2013, the Ebola virus (EBOV) was known to produce recurrent outbreaks in remote villages near tropical rainforests in Central Africa, never exceeding a few hundred cases with very high virulence. Both EBOV’s ability to circulate for several months in large urban human populations and its important mutation rate suggest that EBOV’s virulence could evolve and to some extent adapt to human hosts [2]. Up to now, the high virulence of EBOV in humans was generally thought to be maladaptive, the virus being adapted to circulating in wild animal populations (e.g. fruit bats [3]). As a logical consequence, EBOV virulence could be expected to decrease during long epidemics in humans. The present paper by Sofonea et al. [4] challenges this view and explores how, given EBOV’s life cycle and known epidemiological parameters, virulence is expected to evolve in the human host during long epidemics. The main finding of the paper is that there is no chance that EBOV’s virulence decreases in the short and long terms. The main underlying mechanism is that EBOV is also transmitted by dead bodies, which limits the cost of virulence. In itself the idea that selection should select for higher virulence in diseases that are also transmitted after host death will sound intuitive for most evolutionary epidemiologists. The accomplishment of the paper is to make a very strong case that the parameter range where virulence could decrease is very small. The paper further provides scientifically grounded arguments in favor of the safe management of corpses. Safe burial of corpses is culturally difficult to impose. The present paper shows that in addition to instantaneously decreasing the spread of the virus, safe burial may limit virulence increase in the short term and favor of less virulent strains in the long term. Altogether these results make a timely and important contribution to the knowledge and understanding of EBOV. References [1] World Health Organization. 2016. WHO: Ebola situation report - 10 June 2016. [2] Kupferschmidt K. 2014. Imagining Ebola’s next move. Science 346: 151–152. doi: 10.1126/science.346.6206.151 [3] Leroy EM, Kumulungui B, Pourrut X, Rouquet P, Hassanin A, Yaba P, Délicat A, Paweska, Gonzalez JP and Swanepoel R. 2005. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 438: 575–576. doi: 10.1038/438575a [4] Sofonea MT, Aldakak L, Boullosa LFVV and Alizon S. 2017. Can Ebola Virus evolve to be less virulent in humans? bioRxiv 108589, ver. 3 of 19th May 2017; doi: 10.1101/108589 | Can Ebola Virus evolve to be less virulent in humans? | Mircea T. Sofonea, Lafi Aldakak, Luis Fernando Boullosa, Samuel Alizon | Understanding Ebola Virus (EBOV) virulence evolution is not only timely but also raises specific questions because it causes one pf the most virulent human infections and it is capable of transmission after the death of its host. Using a compartme... |  | Evolutionary Epidemiology | Virginie Ravigné | 2017-02-15 13:25:58 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer