Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors▲ | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

18 Jun 2020

Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in betweenFanny Pouyet and Kimberly J. Gilbert http://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11490Molecular evolution through the joint lens of genomic and population processes.Recommended by Guillaume Achaz based on reviews by Benoit Nabholz and 1 anonymous reviewerIn their perspective article, F Pouyet and KJ Gilbert (2020), propose an interesting overview of all the processes that sculpt patterns of molecular evolution. This well documented article covers most (if not all) important facets of the recurrent debate that has marked the history of molecular evolution: the relative importance of natural selection and neutral processes (i.e. genetic drift). I particularly enjoyed reading this review, that instead of taking a clear position on the debate, catalogs patiently every pieces of information that can help understand how patterns we observed at the genome level, can be understood from a selectionnist point of view, from a neutralist one, and, to quote their title, from "everything in between". The review covers the classical objects of interest in population genetics (genetic drift, selection, demography and structure) but also describes several genomic processes (meiotic drive, linked selection, gene conversion and mutation processes) that obscure the interpretation of these population processes. The interplay between all these processes is very complex (to say the least) and have resulted in many cases in profound confusions while analyzing data. It is always very hard to fully acknowledge our ignorance and we have many times payed the price of model misspecifications. This review has the grand merit to improve our awareness in many directions. Being able to cover so many aspects of a wide topic, while expressing them simply and clearly, connecting concepts and observations from distant fields, is an amazing "tour de force". I believe this article constitutes an excellent up-to-date introduction to the questions and problems at stake in the field of molecular evolution and will certainly also help established researchers by providing them a stimulating overview supported with many relevant references. References [1] Pouyet F, Gilbert KJ (2020) Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between. arXiv:1909.11490 [q-bio]. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. url:https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11490 | Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between | Fanny Pouyet and Kimberly J. Gilbert | <p>A major goal of molecular evolutionary biology is to identify loci or regions of the genome under selection versus those evolving in a neutral manner. Correct identification allows accurate inference of the evolutionary process and thus compreh... |  | Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Guillaume Achaz | 2019-09-26 10:58:10 | View | |

13 Jan 2019

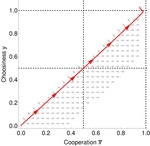

Why cooperation is not running awayFélix Geoffroy, Nicolas Baumard, Jean-Baptiste André https://doi.org/10.1101/316117A nice twist on partner choice theoryRecommended by Erol Akcay based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersIn this paper, Geoffroy et al. [1] deal with partner choice as a mechanism of maintaining cooperation, and argues that rather than being unequivocally a force towards improved payoffs to everyone through cooperation, partner choice can lead to “over-cooperation” where individuals can evolve to invest so much in cooperation that the costs of cooperating partially or fully negate the benefits from it. This happens when partner choice is consequential and effective, i.e., when interactions are long (so each decision to accept or reject a partner is a bigger stake) and when meeting new partners is frequent when unpaired (so that when one leaves an interaction one can find a new partner quickly). Geoffroy et al. [1] show that this tendency to select for overcooperation under such regimes can be counteracted if individuals base their acceptance-rejection of partners not just on the partner cooperativeness, but also on their own. By using tools from matching theory in economics, they show that plastic partner choice generates positive assortment between cooperativeness of the partners, and in the extreme case of perfectly assortative pairings, makes the pair the unit of selection, which selects for maximum total payoff. References [1] Geoffroy, F., Baumard, N., & Andre, J.-B. (2019). Why cooperation is not running away. bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/316117 | Why cooperation is not running away | Félix Geoffroy, Nicolas Baumard, Jean-Baptiste André | <p>A growing number of experimental and theoretical studies show the importance of partner choice as a mechanism to promote the evolution of cooperation, especially in humans. In this paper, we focus on the question of the precise quantitative lev... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Theory | Erol Akcay | 2018-05-15 10:32:51 | View | |

07 Sep 2018

Parallel pattern of differentiation at a genomic island shared between clinal and mosaic hybrid zones in a complex of cryptic seahorse lineagesFlorentine Riquet, Cathy Liautard-Haag, Lucy Woodall, Carmen Bouza, Patrick Louisy, Bojan Hamer, Francisco Otero-Ferrer, Philippe Aublanc, Vickie Béduneau, Olivier Briard, Tahani El Ayari, Sandra Hochscheid, Khalid Belkhir, Sophie Arnaud-Haond, Pierre-Alexandre Gagnaire, Nicolas Bierne https://doi.org/10.1101/161786Genomic parallelism in adaptation to orthogonal environments in sea horsesRecommended by Yaniv Brandvain based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersStudies in speciation genomics have revealed that gene flow is quite common, and that despite this, species can maintain their distinct environmental adaptations. Although researchers are still elucidating the genomic mechanisms by which species maintain their adaptations in the face of gene flow, this often appears to involve few diverged genomic regions in otherwise largely undifferentiated genomes. In this preprint [1], Riquet and colleagues investigate the genetic structuring and patterns of parallel evolution in the long-snouted seahorse. References [1] Riquet, F., Liautard-Haag, C., Woodall, L., Bouza, C., Louisy, P., Hamer, B., Otero-Ferrer, F., Aublanc, P., Béduneau, V., Briard, O., El Ayari, T., Hochscheid, S. Belkhir, K., Arnaud-Haond, S., Gagnaire, P.-A., Bierne, N. (2018). Parallel pattern of differentiation at a genomic island shared between clinal and mosaic hybrid zones in a complex of cryptic seahorse lineages. bioRxiv, 161786, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/161786 | Parallel pattern of differentiation at a genomic island shared between clinal and mosaic hybrid zones in a complex of cryptic seahorse lineages | Florentine Riquet, Cathy Liautard-Haag, Lucy Woodall, Carmen Bouza, Patrick Louisy, Bojan Hamer, Francisco Otero-Ferrer, Philippe Aublanc, Vickie Béduneau, Olivier Briard, Tahani El Ayari, Sandra Hochscheid, Khalid Belkhir, Sophie Arnaud-Haond, Pi... | <p>Diverging semi-isolated lineages either meet in narrow clinal hybrid zones, or have a mosaic distribution associated with environmental variation. Intrinsic reproductive isolation is often emphasized in the former and local adaptation in the la... |  | Hybridization / Introgression, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Yaniv Brandvain | Kathleen Lotterhos, Sarah Fitzpatrick | 2017-07-11 13:12:40 | View |

25 Sep 2023

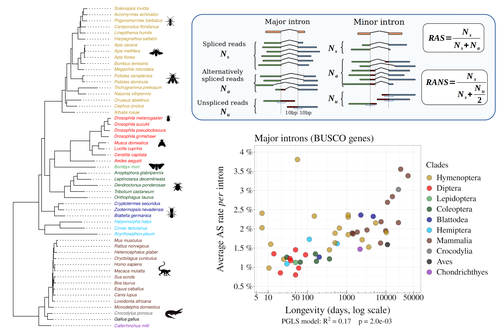

Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoansFlorian Benitiere, Anamaria Necsulea, Laurent Duret https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519597The drift barrier hypothesis and the limits to alternative splicing accuracyRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Lars M. Jakt and 2 anonymous reviewersAccurate information flow is central to living systems. The continuity of genomes through generations as well as the reproducible functioning and survival of the individual organisms require a faithful information transfer during replication, transcription and translation. The differential efficiency of natural selection against “mistakes” results in decreasing fidelity rates for replication, transcription and translation. At each level in the information flow chain (replication, transcription, translation), numerous complex molecular systems have evolved and been selected for preventing, identifying and, when possible, correcting or removing such “mistakes” arising during information transfer. However, fidelity cannot be improved ad infinitum. First, because of the limits imposed by the physical nature of the processes of copying and recoding information over different molecular supports: all mechanisms ensuring fidelity during biological information transfer ultimately rely on chemical kinetics and thermodynamics. The more accurate a copying process is, the lower the synthesis rate and the higher the energetic cost of correcting errors. Second, because of the limits imposed by random genetic drift: natural selection cannot effectively act on an allele that contributes with a small differential advantage unless effective population size is large. If s <1/Ne (or s <1/(2Ne) in diploids) the allele frequency in the population is de facto subject to neutral drift processes. In their preprint “Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans”, Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret explore the validity of this last mentioned “drift barrier” hypothesis for the case study of alternative splicing diversity in eukaryotes (Bénitière et al. 2022). Splicing refers to an ensemble of eukaryotic molecular processes mediated by a large number of proteins and ribonucleoproteins and involving nucleotide sequence recognition, that uses as a molecular substrate a precursor messenger RNA (mRNA), directly transcribed from the DNA, and produces a mature mRNA by removing introns and joining exons (Chow et al. 1977). Alternative splicing refers to the case in which different molecular species of mature mRNAs can be produced, either by cis-splicing processes acting on the same precursor mRNA, e.g. by varying the presence/absence of different exons or by varying the exon-exon boundaries, or by trans-splicing processes, joining exons from different precursor mRNA molecules. The diversity of mRNA molecular species generated by alternative splicing enlarges the molecular phenotypic space that can be generated from the same genotype. In humans, alternative splicing occurs in around 95% of the ca. 20,000 genes, resulting in ca. 100,000 medium-to-high abundance transcripts (Pan et al. 2008). In multicellular organisms, the frequency of alternatively spliced mRNAs varies between tissues and across ontogeny, often in a switch-like pattern (Wang et al. 2008). In the molecular and cell biology community, it is commonly accepted that splice variants contribute with specific functions (Marasco and Kornblihtt 2023) although there exists a discussion around the functional nature of low-frequency splice variants (see for instance the debate between Tress et al. 2017 and Blencowe 2017). The origin, diversity, regulation and evolutionary advantage of alternative splicing constitutes thus a playground of the selectionist-neutralist debate, with one extreme considering that most splice variants are mere “mistakes” of the splicing process (Pickrell et al. 2010), and the other extreme considering that alternative splicing is at the core of complexity in multicellular organisms, as it increases the genome coding potential and allows for a large repertoire of cell types (Chen et al. 2014). In their manuscript, Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret set the cursor towards the neutralist end of the gradient and test the hypothesis of whether the high alternative splice rate in “complex” organisms corresponds to a high rate of splicing “mistakes”, arising from the limit imposed by the drift barrier effect on the power of natural selection to increase accuracy (Bush et al. 2017). In their preprint, the authors convincingly show that in metazoans a fraction of the variation of alternative splicing rate is explained by variation in proxies of population size, so that species with smaller Ne display higher alternative splice rates. They communicate further that abundant splice variants tend to preserve the reading frame more often than low-frequency splice variants, and that the nucleotide splice signals in abundant splice variants display stronger evidence of purifying selection than those in low-frequency splice variants. From all the evidence presented in the manuscript, the authors interpret that “variation in alternative splicing rate is entirely driven by variation in the efficacy of selection against splicing errors”. The authors honestly present some of the limitations of the data used for the analyses, regarding i) the quality of the proxies used for Ne (i.e. body length, longevity and dN/dS ratio); ii) the heterogeneous nature of the RNA sequencing datasets (full organisms, organs or tissues; different life stages, sexes or conditions); and iii) mostly short RNA reads that do not fully span individual introns. Further, data from bacteria do not verify the herein communicated trends, as it has been shown that bacterial species with low population sizes do not display higher transcription error rates (Traverse and Ochman 2016). Finally, it will be extremely interesting to introduce a larger evolutionary perspective on alternative splicing rates encompassing unicellular eukaryotes, in which an intriguing interplay between alternative splicing and gene duplication has been communicated (Hurtig et al. 2020). The manuscript from Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret makes a significant advance to our understanding of the diversity, the origin and the physiology of post-transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms by emphasising the fundamental role of non-adaptive evolutionary processes and the upper limits to splicing accuracy set by genetic drift. References Bénitière F, Necsulea A, Duret L. 2023. Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519597 Blencowe BJ. 2017. The Relationship between Alternative Splicing and Proteomic Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci 42:407–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2017.04.001 Bush SJ, Chen L, Tovar-Corona JM, Urrutia AO. 2017. Alternative splicing and the evolution of phenotypic novelty. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 372:20150474. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0474 Chen L, Bush SJ, Tovar-Corona JM, Castillo-Morales A, Urrutia AO. 2014. Correcting for differential transcript coverage reveals a strong relationship between alternative splicing and organism complexity. Mol Biol Evol 31:1402–1413. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu083 Chow LT, Gelinas RE, Broker TR, Roberts RJ. 1977. An amazing sequence arrangement at the 5’ ends of adenovirus 2 messenger RNA. Cell 12:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(77)90180-5 Hurtig JE, Kim M, Orlando-Coronel LJ, Ewan J, Foreman M, Notice L-A, Steiger MA, van Hoof A. 2020. Origin, conservation, and loss of alternative splicing events that diversify the proteome in Saccharomycotina budding yeasts. RNA 26:1464–1480. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.075655.120 Marasco LE, Kornblihtt AR. 2023. The physiology of alternative splicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 24:242–254. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-022-00545-z Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. 2008. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet 40:1413–1415. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.259 Pickrell JK, Pai AA, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. 2010. Noisy splicing drives mRNA isoform diversity in human cells. PLoS Genet 6:e1001236. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001236 Traverse CC, Ochman H. 2016. Conserved rates and patterns of transcription errors across bacterial growth states and lifestyles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:3311–3316. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1525329113 Tress ML, Abascal F, Valencia A. 2017. Alternative Splicing May Not Be the Key to Proteome Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci 42:98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2016.08.008 Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP, Burge CB. 2008. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 456:470–476. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07509 | Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans | Florian Benitiere, Anamaria Necsulea, Laurent Duret | <p style="text-align: justify;">Most eukaryotic genes undergo alternative splicing (AS), but the overall functional significance of this process remains a controversial issue. It has been noticed that the complexity of organisms (assayed by the nu... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Ignacio Bravo | Anonymous | 2022-12-12 14:00:01 | View |

06 May 2019

When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexualsFlorian Lavigne, Guillaume Martin, Yoann Anciaux, Julien Papaïx, Lionel Roques https://doi.org/10.1101/433235Fisher to the rescueRecommended by François Blanquart and Florence Débarre based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe ability of a population to adapt to a new niche is an important phenomenon in evolutionary biology. The colonisation of a new volcanic island by plant species; the colonisation of a host treated by antibiotics by a-resistant strain; the Ebola virus transmitting from bats to humans and spreading epidemically in Western Africa, are all examples of a population invading a new niche, adapting and eventually establishing in this new environment. Adaptation to a new niche can be studied using source-sink models. In the original environment —the “source”—, the population enjoys a positive growth-rate and is self-sustaining, while in the new environment —the “sink”— the population has a negative growth rate and is able to sustain only by the continuous influx of migrants from the source. Understanding the dynamics of adaptation to the sink environment is challenging from a theoretical standpoint, because it requires modelling the demography of the sink as well as the transient dynamics of adaptation. Moreover, local selection in the sink and immigration from the source create distributions of genotypes that complicate the use of many common mathematical approaches. In their paper, Lavigne et al. [1], develop a new deterministic model of adaptation to a harsh sink environment in an asexual species. The fitness of an individual is maximal when a number of phenotypes are tuned to an optimal value, and declines monotonously as phenotypes are further away from this optimum. This model —called Fisher’s Geometric Model— generates a GxE interaction for fitness because the phenotypic optimum in the sink environment is distinct from that in the source environment [2]. The authors circumvent mathematical difficulties by developing an original approach based on tracking the deterministic dynamics of the cumulant generating function of the fitness distribution in the sink. They derive a number of important results on the dynamics of adaptation to the sink:

In conclusion, this theoretical work presents a method based on Fisher’s Geometric Model and the use of cumulant generating functions to resolve some aspects of adaptation to a sink environment. It generates a number of theoretical predictions for the adaptive colonisation of a sink by an asexual species with some standing genetic variation. It will be a fascinating task to examine whether these predictions hold in experimental evolution systems: will we observe the four phases of the dynamics of mean fitness in the sink environment? Will the rate of adaptation indeed be independent of the immigration rate? Is there an optimal rate of mutation for adaptation to the sink? Such critical tests of the theory will greatly improve our understanding of adaptation to novel environments. References [1] Lavigne, F., Martin, G., Anciaux, Y., Papaïx, J., and Roques, L. (2019). When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexuals. bioRxiv, 433235, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/433235 | When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexuals | Florian Lavigne, Guillaume Martin, Yoann Anciaux, Julien Papaïx, Lionel Roques | <p>The successful establishment of a population into a new empty habitat outside of its initial niche is a phenomenon akin to evolutionary rescue in the presence of immigration. It underlies a wide range of processes, such as biological invasions ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology | François Blanquart | 2018-10-03 20:59:16 | View | |

01 Mar 2021

Social Conflicts in Dictyostelium discoideum : A Matter of ScalesForget, Mathieu; Adiba, Sandrine; De Monte, Silvia https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03088868/The cell-level perspective in social conflicts in Dictyostelium discoideumRecommended by Jeremy Van Cleve based on reviews by Peter Conlin and ?The social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum is an important model system for the study of cooperation and multicellularity as is has both unicellular and aggregative life phases. In the aggregative phase, which typically occurs when nutrients are limiting, individual cells eventually gather together to form a fruiting bodies whose spores may be dispersed to another, better, location and whose stalk cells, which support the spores, die. This extreme form of cooperation has been the focus of numerous studies that have revealed the importance genetic relatedness and kin selection (Hamilton 1964; Lehmann and Rousset 2014) in explaining the maintenance of this cooperative collective behavior (Strassmann et al. 2000; Kuzdzal-Fick et al. 2011; Strassmann and Queller 2011). However, much remains unknown with respect to how the interactions between individual cells, their neighbors, and their environment produce cooperative behavior at the scale of whole groups or collectives. In this preprint, Forget et al. (2021) describe how the D. discoideum system is crucial in this respect because it allows these cellular-level interactions to be studied in a systematic and tractable manner. References Forget, M., Adiba, S. and De Monte, S.(2021) Social conflicts in *Dictyostelium discoideum *: a matter of scales. HAL, hal-03088868, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03088868/ Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour. II. Journal of theoretical biology, 7(1), 17-52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(64)90039-6 Kuzdzal-Fick, J. J., Fox, S. A., Strassmann, J. E., and Queller, D. C. (2011). High relatedness is necessary and sufficient to maintain multicellularity in Dictyostelium. Science, 334(6062), 1548-1551. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1213272 Lehmann, L., and Rousset, F. (2014). The genetical theory of social behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1642), 20130357. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0357 Strassmann, J. E., and Queller, D. C. (2011). Evolution of cooperation and control of cheating in a social microbe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(Supplement 2), 10855-10862. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1102451108 Strassmann, J. E., Zhu, Y., & Queller, D. C. (2000). Altruism and social cheating in the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature, 408(6815), 965-967. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/35050087 Thompson, C. R., & Kay, R. R. (2000). Cell-fate choice in Dictyostelium: intrinsic biases modulate sensitivity to DIF signaling. Developmental biology, 227(1), 56-64. doi: https://doi.org/10.1006/dbio.2000.9877 | Social Conflicts in Dictyostelium discoideum : A Matter of Scales | Forget, Mathieu; Adiba, Sandrine; De Monte, Silvia | <p>The 'social amoeba' Dictyostelium discoideum, where aggregation of genetically heterogeneous cells produces functional collective structures, epitomizes social conflicts associated with multicellular organization. 'Cheater' populations that hav... | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Experimental Evolution | Jeremy Van Cleve | 2020-08-28 10:37:21 | View | ||

06 Oct 2017

Evolutionary analysis of candidate non-coding elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes in vertebratesFrancisco J. Novo https://doi.org/10.1101/150482Combining molecular information on chromatin organisation with eQTLs and evolutionary conservation provides strong candidates for the evolution of gene regulation in mammalian brainsRecommended by Marc Robinson-Rechavi based on reviews by Marc Robinson-Rechavi and Charles DankoIn this manuscript [1], Francisco J. Novo proposes candidate non-coding genomic elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes. What is very nice about this study is the way in which public molecular data, including physical interaction data, is used to leverage recent advances in our understanding to molecular mechanisms of gene regulation in an evolutionary context. More specifically, evolutionarily conserved non coding sequences are combined with enhancers from the FANTOM5 project, DNAse hypersensitive sites, chromatin segmentation, ChIP-seq of transcription factors and of p300, gene expression and eQTLs from GTEx, and physical interactions from several Hi-C datasets. The candidate regulatory regions thus identified are linked to candidate regulated genes, and the author shows their potential implication in brain development. While the results are focused on a small number of genes, this allows to verify features of these candidates in great detail. This study shows how functional genomics is increasingly allowing us to fulfill the promises of Evo-Devo: understanding the molecular mechanisms of conservation and differences in morphology. References [1] Novo, FJ. 2017. Evolutionary analysis of candidate non-coding elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes in vertebrates. bioRxiv, 150482, ver. 4 of Sept 29th, 2017. doi: 10.1101/150482 | Evolutionary analysis of candidate non-coding elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes in vertebrates | Francisco J. Novo | <p>Many non-coding regulatory elements conserved in vertebrates regulate the expression of genes involved in development and play an important role in the evolution of morphology through the rewiring of developmental gene networks. Available biolo... |  | Genome Evolution | Marc Robinson-Rechavi | Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Charles Danko | 2017-06-29 08:55:41 | View |

30 Oct 2023

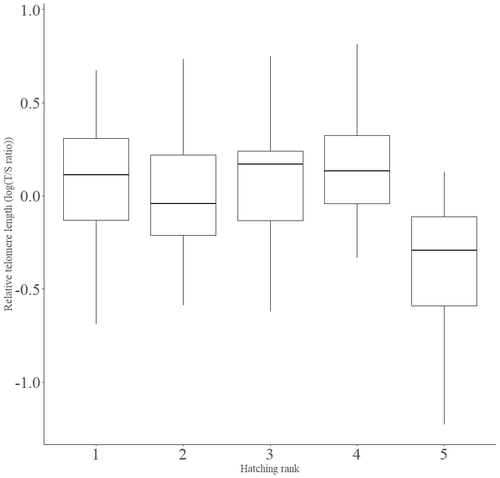

Telomere length vary with sex, hatching rank and year of birth in little owls, Athene noctuaFrançois Criscuolo, Inès Fache, Bertrand Scaar, Sandrine Zahn, Josefa Bleu https://doi.org/10.32942/X2BS3SDeciphering the relative contribution of environmental and biological factors driving telomere length in nestlingsRecommended by Jean-François Lemaitre based on reviews by Florentin Remot and 1 anonymous reviewerThe search for physiological markers of health and survival in wild animal populations is attracting a great deal of interest. At present, there is no (and may never be) consensus on such a single, robust marker but of all the proposed physiological markers, telomere length is undoubtedly the most widely studied in the field of evolutionary ecology (Monaghan et al., 2022). Broadly speaking, telomeres are non-coding DNA sequences located at the end of chromosomes in eukaryotes, protecting genomic DNA against oxidative stress and various detrimental processes (e.g. DNA end-joining) and thus maintaining genome stability (Blackburn et al., 2015). However, in most somatic cells from the vast majority of the species, telomere sequences are not replicated and telomere length progressively declines with increased age (Remot et al., 2022). This shortening of telomere length upon a critical level is causally linked to cellular senescence and has been invoked as one of the primary causes of the aging process (López-Otín et al., 2023). Studies performed in both captive and wild populations of animals have further demonstrated that short telomeres (or telomere sequences with a fast attrition rate) are to some extent associated with an increased risk of mortality, even if the magnitude of this association largely differs between species and populations (Wilbourn et al., 2018). The repeated observations of associations between telomere length and mortality risk have called for studies seeking to identify the ecological and biological factors that – beyond chronological age – shape the between-individual variability in telomere length. A wide spectrum of environmental stressors such as the level of exposure to pathogens or the degree of human disturbances has been proposed as possible modulators of telomere dynamics (see Chatelain et al., 2019). However, within species, the relative contribution of various ecological and biological factors on telomere length has been rarely quantified. In that context, the study of Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) constitutes a timely attempt to decipher the relative contribution of environmental and biological factors driving telomere length in nestlings (i.e. when individuals are between 15 and 35 days of age) from a wild population of little owls, Athene noctua. In addition to chronological age, Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) analysed the effects of two environmental variables (i.e. cohort and habitat quality) as well as three life history traits (i.e. hatching rank, sex and body condition). Among these traits, sex was found to impact nestling’s telomere length with females carrying longer telomeres than males. Traditionally, the among-individuals variability in telomere length during the juvenile period is interpreted as a direct consequence of differences in growth allocation. Fast-growing individuals are typically supposed to undergo more cell divisions and a higher exposure to oxidative stress, which ultimately shortens telomeres (Monaghan & Ozanne, 2018). Whether - despite a slightly female-biased sexual size dimorphism - male little owls display a condensed period of fast growth that could explain their shorter telomere is yet to be determined. Future studies should also explore the consequences of these sex differences in telomere length in terms of mortality risk. In birds, it has been observed that telomere length during early life can predict lifespan (see Heidinger et al., 2012 in zebra finches, Taeniopygia guttata), suggesting that females little owls might live longer than their conspecific males. Yet, adult mortality is generally female-biased in birds (Liker & Székely, 2005) and whether little owls constitute an exception to this rule - possibly mediated by sex-specific telomere dynamics - remains to be explored. Quite surprisingly, the present study in little owls did not evidence any clear effect of environmental conditions on nestling’s telomere length, at both temporal and special scales. While a trend for a temporal effect was detected with telomere length being slightly shorter for nestling born the last year of the study (out of 4 years analysed), habitat quality (measured by the proportion of meadow and orchards in the nest environment) had absolutely no impact on nestling telomere length. Recently published studies in wild populations of vertebrates have highlighted the detrimental effects of harsh environmental conditions on telomere length (e.g. Dupoué et al., 2022 in common lizards, Zootoca vivipara), arguing for a key role of telomere dynamics in the emerging field of conservation physiology. While we can recognize the relevance of such an integrative approach, especially in the current context of climate change, the study by Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) reminds us that the relationships between environmental conditions and telomere dynamics are far from straightforward. Depending on the species and its life history, telomere length in early life could indeed capture very different environmental signals. References Blackburn, E. H., Epel, E. S., & Lin, J. (2015). Human telomere biology: A contributory and interactive factor in aging, disease risks, and protection. Science, 350(6265), 1193-1198. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab3389 | Telomere length vary with sex, hatching rank and year of birth in little owls, *Athene noctua* | François Criscuolo, Inès Fache, Bertrand Scaar, Sandrine Zahn, Josefa Bleu | <p>Telomeres are non-coding DNA sequences located at the end of linear chromosomes, protecting genome integrity. In numerous taxa, telomeres shorten with age and telomere length (TL) is positively correlated with longevity. Moreover, TL is also af... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Jean-François Lemaitre | 2023-03-07 09:44:32 | View | |

20 Nov 2023

Phenotypic stasis with genetic divergenceFrançois Mallard, Luke Noble, Thiago Guzella, Bruno Afonso, Charles F. Baer, Henrique Teotónio https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.28.493856Phenotypic stasis despite genetic divergence and differentiation in Caenorhabditis elegans.Recommended by Frédéric Guillaume based on reviews by Benoit Pujol and Pedro Simões based on reviews by Benoit Pujol and Pedro Simões

Explaining long periods of evolutionary stasis, the absence of change in trait means over geological times, despite the existence of abundant genetic variation in most traits has challenged evolutionary theory since Darwin's theory of evolution by gradual modification (Estes & Arnold 2007). Stasis observed in contemporary populations is even more daunting since ample genetic variation is usually coupled with the detection of selection differentials (Kruuk et al. 2002, Morrissey et al. 2010). Moreover, rapid adaptation to environmental changes in contemporary populations, fuelled by standing genetic variation provides evidence that populations can quickly respond to an adaptive challenge. Explanations for evolutionary stasis usually invoke stabilizing selection as a main actor, whereby optimal trait values remain roughly constant over long periods of time despite small-scale environmental fluctuations. Genetic correlation among traits may also play a significant role in constraining evolutionary changes over long timescales (Schluter 1996). Yet, genetic constraints are rarely so strong as to completely annihilate genetic changes, and they may evolve. Patterns of genetic correlations among traits, as captured in estimates of the G-matrix of additive genetic co-variation, are subject to changes over generations under the action of drift, migration, or selection, among other causes (Arnold et al. 2008). Therefore, under the assumption of stabilizing selection on a set of traits, phenotypic stasis and genetic divergence in patterns of trait correlations may both be observed when selection on trait correlations is weak relative to its effect on trait means. Mallard et al. (2023) set out to test whether selection or drift may explain the divergence in genetic correlation among traits in experimental lines of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and whether stabilizing selection may be a driver of phenotypic stasis. To do so, they analyzed the evolution of locomotion behavior traits over 100 generations of lab evolution in a constant and homogeneous environment after 140 generations of domestication from a largely differentiated set of founder populations. The locomotion traits were transition rates between movement states and direction (still, forward or backward movement). They could estimate the traits' broad-sense G-matrix in three populations at two generations (50 and 100), and in the ancestral mixed population. Similarly, they estimated the shape of the selection surface by regressing locomotion behavior on fertility. Armed with both G-matrix and surface estimates, they could test whether the G's orientation matched selection's orientation and whether changes in G were constrained by selection. They found stasis in trait mean over 100 generations but divergence in the amount and orientation of the genetic variation of the traits relative to the ancestral population. The selected populations changed orientation of their G-matrices and lost genetic variation during the experiment in agreement with a model of genetic drift on quantitative traits. Their estimates of selection also point to mostly stabilizing selection on trait combinations with weak evidence of disruptive selection, suggesting a saddle-shaped selection surface. The evolutionary responses of the experimental populations were mostly consistent with small differentiation in the shape of G-matrices during the 100 generations of stabilizing selection. Mallard et al. (2023) conclude that phenotypic stasis was maintained by stabilizing selection and drift in their experiment. They argue that their findings are consistent with a "table-top mountain" model of stabilizing selection, whereby the population is allowed some wiggle room around the trait optimum, leaving space for random fluctuations of trait variation, and especially trait co-variation. The model is an interesting solution that might explain how stasis can be maintained over contemporary times while allowing for random differentiation of trait genetic co-variation. Whether such differentiation can then lead to future evolutionary divergence once replicated populations adapt to a new environment is an interesting idea to follow. References Arnold, S. J., Bürger, R., Hohenlohe, P. A., Ajie, B. C. and Jones, A. G. 2008. Understanding the evolution and stability of the G-matrix. Evolution 62(10): 2451-2461. | Phenotypic stasis with genetic divergence | François Mallard, Luke Noble, Thiago Guzella, Bruno Afonso, Charles F. Baer, Henrique Teotónio | <p style="text-align: justify;">Whether or not genetic divergence in the short-term of tens to hundreds of generations is compatible with phenotypic stasis remains a relatively unexplored problem. We evolved predominantly outcrossing, genetically ... | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Experimental Evolution, Quantitative Genetics | Frédéric Guillaume | 2022-09-01 14:32:53 | View | ||

21 Nov 2018

Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infectionFrederic Bertels, Karin J Metzner, Roland R Regoes https://doi.org/10.1101/168260Is convergence an evidence for positive selection?Recommended by Guillaume Achaz based on reviews by Jeffrey Townsend and 1 anonymous reviewerThe preprint by Bertels et al. [1] reports an interesting application of the well-accepted idea that positively selected traits (here variants) can appear several times independently; think about the textbook examples of flight capacity. Hence, the authors assume that reciprocally convergence implies positive selection. The methodology becomes then, in principle, straightforward as one can simply count variants in independent datasets to detect convergent mutations. References [1] Bertels, F., Metzner, K. J., & Regoes R. R. (2018). Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infection. BioRxiv, 168260, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/168260 | Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infection | Frederic Bertels, Karin J Metzner, Roland R Regoes | <p>Convergent evolution describes the process of different populations acquiring similar phenotypes or genotypes. Complex organisms with large genomes only rarely and only under very strong selection converge to the same genotype. In contrast, ind... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Guillaume Achaz | 2017-07-26 08:39:17 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer