Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

02 Sep 2022

Introgression between highly divergent sea squirt genomes: an adaptive breakthrough?Christelle Fraïsse, Alan Le Moan, Camille Roux, Guillaume Dubois, Claire Daguin-Thiébaut, Pierre-Alexandre Gagnaire, Frédérique Viard, Nicolas Bierne https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.22.485319A match made in the Anthropocene: human-mediated adaptive introgression across a speciation continuumRecommended by Fernando Racimo based on reviews by Michael Westbury, Andrew Foote and Erin CalfeeThe long-distance transport and introduction of new species by humans is increasingly leading divergent lineages to interact, and sometimes interbreed, even after thousands or millions of years of separation. It is thus of prime importance to understand the consequences of these contemporary admixture events on the evolutionary fitness of interacting organisms, and their ecological implications. Ciona robusta and Ciona intestinalis are two species of sea squirts that diverged between 1.5 and 2 million years ago and recently came into contact again. This occurred through human-mediated introduction of C. robusta (native to the Northwest Pacific) into the range of C. intestinalis (the English channeled Northeast Atlantic). In this study, Fraïsse et al. (2022) follow up on earlier work by Le Moan et al. (2021), who had identified a long genomic hotspot of introgression of C. robusta ancestry segments in chromosome 5 of C. intestinalis. The hotspot bears suggestive evidence of positive selection and the authors aimed to investigate this further using fully phased whole-genome sequences. The authors narrow down on the exact boundaries of the introgressed region, and make a compelling case that it has been the likely target of positive selection after introgression, using various complementary approaches based on patterns of population differentiation, haplotype structure and local levels of diversity in the region. Using extensive demographic modeling, they also show that the introgression event was likely recent (approximately 75 years ago), and distinct from other tracts in the C. intestinalis genome that are likely a product of more ancient episodes of interbreeding in the past 30,000 years. Narrowing down on the potential drivers of selection, the authors show that candidate SNPs in the region overlap with the cytochrome family 2 subfamily U gene - involved in the detoxification of exogenous compounds - potentially reflecting adaptation to chemicals encountered in the sea squirt's environment. There also appears to be copy number variation at the candidate SNPs, which provides clues into the adaptation mechanism in the region. All reviewers agreed that the work carried out by the authors is elegant and the results are robustly supported and well presented. In a round of reviews, various clarifications of the manuscript were suggested by the reviewers, including on the quality of the newly generated sequencing data, and some suggestions for qualifications on the conclusions reached by the authors as well as changes in the figures to increase their clarity. The authors addressed the different concerns of the reviewers, and the new version is much improved. This study into human-mediated introgression and its consequences for adaptation is, in my view, both well thought-out and executed. I therefore provide an enthusiastic recommendation of this manuscript. References Fraïsse C, Le Moan A, Roux C, Dubois G, Daguin-Thiébaut C, Gagnaire P-A, Viard F and Bierne N (2022) Introgression between highly divergent sea squirt genomes: an adaptive breakthrough? bioRxiv, 2022.03.22.485319, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.22.485319 Le Moan A, Roby C, Fraïsse C, Daguin-Thiébaut C, Bierne N, Viard F (2021) An introgression breakthrough left by an anthropogenic contact between two ascidians. Molecular Ecology, 30, 6718–6732. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16189 | Introgression between highly divergent sea squirt genomes: an adaptive breakthrough? | Christelle Fraïsse, Alan Le Moan, Camille Roux, Guillaume Dubois, Claire Daguin-Thiébaut, Pierre-Alexandre Gagnaire, Frédérique Viard, Nicolas Bierne | <p style="text-align: justify;">Human-mediated introductions are reshuffling species distribution on a global scale. Consequently, an increasing number of allopatric taxa are now brought into contact, promoting introgressive hybridization between ... |  | Adaptation, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics | Fernando Racimo | 2022-04-14 15:30:42 | View | |

13 Apr 2023

The landscape of nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster is shaped by mutation rate variationGustavo V Barroso, Julien Y Dutheil https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.16.460667An unusual suspect: the mutation landscape as a determinant of local variation in nucleotide diversityRecommended by Fernando Racimo based on reviews by David Castellano and 1 anonymous reviewerSometimes, important factors for explaining biological processes fall through the cracks, and it is only through careful modeling that their importance eventually comes out to light. In this study, Barroso and Dutheil introduce a new method based on the sequentially Markovian coalescent (SMC, Marjoran and Wall 2006) for jointly estimating local recombination and coalescent rates along a genome. Unlike previous SMC-based methods, however, their method can also co-estimate local patterns of variation in mutation rates. This is a powerful improvement which allows them to tackle questions about the reasons for the extensive variation in nucleotide diversity across the chromosomes of a species - a problem that has plagued the minds of population geneticists for decades (Begun and Aquadro 1992, Andolfatto 2007, McVicker et al., 2009, Pouyet and Gilbert 2021). The authors find that variation in de novo mutation rates appears to be the most important factor in determining nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster. Though seemingly contradicting previous attempts at addressing this problem (Comeron 2014), they take care to investigate and explain why that might be the case. Barroso and Dutheil have also taken care to carefully explain the details of their new approach and have carried a very thorough set of analyses comparing competing explanations for patterns of nucleotide variation via causal modeling. The reviewers raised several issues involving choices made by the authors in their analysis of variance partitioning, the proper evaluation of the role of linked selection and the recombination rate estimates emerging from their model. These issues have all been extensively addressed by the authors, and their conclusions seem to remain robust. The study illustrates why the mutation landscape should not be ignored as an important determinant of local variation in genetic diversity, and opens up questions about the generalizability of these results to other organisms. REFERENCES Andolfatto, P. (2007). Hitchhiking effects of recurrent beneficial amino acid substitutions in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome research, 17(12), 1755-1762. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.6691007 Barroso, G. V., & Dutheil, J. Y. (2021). The landscape of nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster is shaped by mutation rate variation. bioRxiv, 2021.09.16.460667, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.16.460667 Begun, D. J., & Aquadro, C. F. (1992). Levels of naturally occurring DNA polymorphism correlate with recombination rates in D. melanogaster. Nature, 356(6369), 519-520. https://doi.org/10.1038/356519a0 Comeron, J. M. (2014). Background selection as baseline for nucleotide variation across the Drosophila genome. PLoS Genetics, 10(6), e1004434. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004434 Marjoram, P., & Wall, J. D. (2006). Fast" coalescent" simulation. BMC genetics, 7, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-7-16 McVicker, G., Gordon, D., Davis, C., & Green, P. (2009). Widespread genomic signatures of natural selection in hominid evolution. PLoS genetics, 5(5), e1000471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000471 Pouyet, F., & Gilbert, K. J. (2021). Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between. Peer Community Journal, 1, e27. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.16 | The landscape of nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster is shaped by mutation rate variation | Gustavo V Barroso, Julien Y Dutheil | <p style="text-align: justify;">What shapes the distribution of nucleotide diversity along the genome? Attempts to answer this question have sparked debate about the roles of neutral stochastic processes and natural selection in molecular evolutio... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics | Fernando Racimo | 2022-10-30 07:52:07 | View | |

06 May 2019

When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexualsFlorian Lavigne, Guillaume Martin, Yoann Anciaux, Julien Papaïx, Lionel Roques https://doi.org/10.1101/433235Fisher to the rescueRecommended by François Blanquart and Florence Débarre based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe ability of a population to adapt to a new niche is an important phenomenon in evolutionary biology. The colonisation of a new volcanic island by plant species; the colonisation of a host treated by antibiotics by a-resistant strain; the Ebola virus transmitting from bats to humans and spreading epidemically in Western Africa, are all examples of a population invading a new niche, adapting and eventually establishing in this new environment. Adaptation to a new niche can be studied using source-sink models. In the original environment —the “source”—, the population enjoys a positive growth-rate and is self-sustaining, while in the new environment —the “sink”— the population has a negative growth rate and is able to sustain only by the continuous influx of migrants from the source. Understanding the dynamics of adaptation to the sink environment is challenging from a theoretical standpoint, because it requires modelling the demography of the sink as well as the transient dynamics of adaptation. Moreover, local selection in the sink and immigration from the source create distributions of genotypes that complicate the use of many common mathematical approaches. In their paper, Lavigne et al. [1], develop a new deterministic model of adaptation to a harsh sink environment in an asexual species. The fitness of an individual is maximal when a number of phenotypes are tuned to an optimal value, and declines monotonously as phenotypes are further away from this optimum. This model —called Fisher’s Geometric Model— generates a GxE interaction for fitness because the phenotypic optimum in the sink environment is distinct from that in the source environment [2]. The authors circumvent mathematical difficulties by developing an original approach based on tracking the deterministic dynamics of the cumulant generating function of the fitness distribution in the sink. They derive a number of important results on the dynamics of adaptation to the sink:

In conclusion, this theoretical work presents a method based on Fisher’s Geometric Model and the use of cumulant generating functions to resolve some aspects of adaptation to a sink environment. It generates a number of theoretical predictions for the adaptive colonisation of a sink by an asexual species with some standing genetic variation. It will be a fascinating task to examine whether these predictions hold in experimental evolution systems: will we observe the four phases of the dynamics of mean fitness in the sink environment? Will the rate of adaptation indeed be independent of the immigration rate? Is there an optimal rate of mutation for adaptation to the sink? Such critical tests of the theory will greatly improve our understanding of adaptation to novel environments. References [1] Lavigne, F., Martin, G., Anciaux, Y., Papaïx, J., and Roques, L. (2019). When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexuals. bioRxiv, 433235, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/433235 | When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexuals | Florian Lavigne, Guillaume Martin, Yoann Anciaux, Julien Papaïx, Lionel Roques | <p>The successful establishment of a population into a new empty habitat outside of its initial niche is a phenomenon akin to evolutionary rescue in the presence of immigration. It underlies a wide range of processes, such as biological invasions ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology | François Blanquart | 2018-10-03 20:59:16 | View | |

11 Jul 2022

Mutualists construct the ecological conditions that trigger the transition from parasitismLeo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Matthias Rohr, Camille Nous, Sebastien Ibanez https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.08.18.456759Give them some space: how spatial structure affects the evolutionary transition towards mutualistic symbiosisRecommended by Francois Massol based on reviews by Eva Kisdi and 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Eva Kisdi and 3 anonymous reviewers

The evolution of mutualistic symbiosis is a puzzle that has fascinated evolutionary ecologist for quite a while. Data on transitions between symbiotic bacterial ways of life has evidenced shifts from mutualism towards parasitism and vice versa (Sachs et al., 2011), so there does not seem to be a strong determinism on those transitions. From the host’s perspective, mutualistic symbiosis implies at the very least some form of immune tolerance, which can be costly (e.g. Sorci, 2013). Empirical approaches thus raise very important questions: How can symbiosis turn from parasitism into mutualism when it seemingly needs such a strong alignment of selective pressures on both the host and the symbiont? And yet why is mutualistic symbiosis so widespread and so important to the evolution of macro-organisms (Margulis, 1998)? While much of the theoretical literature on the evolution of symbiosis and mutualism has focused on either the stability of such relationships when non-mutualists can invade the host-symbiont system (e.g. Ferrière et al., 2007) or the effect of the mode of symbiont transmission on the evolutionary dynamics of mutualism (e.g. Genkai-Kato and Yamamura, 1999), the question remains whether and under which conditions parasitic symbiosis can turn into mutualism in the first place. Earlier results suggested that spatial demographic heterogeneity between host populations could be the leading determinant of evolution towards mutualism or parasitism (Hochberg et al., 2000). Here, Ledru et al. (2022) investigate this question in an innovative way by simulating host-symbiont evolutionary dynamics in a spatially explicit context. Their hypothesis is intuitive but its plausibility is difficult to gauge without a model: Does the evolution towards mutualism depend on the ability of the host and symbiont to evolve towards close-range dispersal in order to maintain clusters of efficient host-symbiont associations, thus outcompeting non-mutualists? I strongly recommend reading this paper as the results obtained by the authors are very clear: competition strength and the cost of dispersal both affect the likelihood of the transition from parasitism to mutualism, and once mutualism has set in, symbiont trait values clearly segregate between highly dispersive parasites and philopatric mutualists. The demonstration of the plausibility of their hypothesis is accomplished with brio and thoroughness as the authors also examine the conditions under which the transition can be reversed, the impact of the spatial range of competition and the effect of mortality. Since high dispersal cost and strong, long-range competition appear to be the main factors driving the evolutionary transition towards mutualistic symbiosis, now is the time for empiricists to start investigating this question with spatial structure in mind. References Ferrière, R., Gauduchon, M. and Bronstein, J. L. (2007) Evolution and persistence of obligate mutualists and exploiters: competition for partners and evolutionary immunization. Ecology Letters, 10, 115-126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.01008.x Genkai-Kato, M. and Yamamura, N. (1999) Evolution of mutualistic symbiosis without vertical transmission. Theoretical Population Biology, 55, 309-323. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.1998.1407 Hochberg, M. E., Gomulkiewicz, R., Holt, R. D. and Thompson, J. N. (2000) Weak sinks could cradle mutualistic symbioses - strong sources should harbour parasitic symbioses. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 13, 213-222. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1420-9101.2000.00157.x Ledru L, Garnier J, Rohr M, Noûs C and Ibanez S (2022) Mutualists construct the ecological conditions that trigger the transition from parasitism. bioRxiv, 2021.08.18.456759, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.18.456759 Margulis, L. (1998) Symbiotic planet: a new look at evolution, Basic Books, Amherst. Sachs, J. L., Skophammer, R. G. and Regus, J. U. (2011) Evolutionary transitions in bacterial symbiosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 10800-10807. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100304108 Sorci, G. (2013) Immunity, resistance and tolerance in bird–parasite interactions. Parasite Immunology, 35, 350-361. https://doi.org/10.1111/pim.12047 | Mutualists construct the ecological conditions that trigger the transition from parasitism | Leo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Matthias Rohr, Camille Nous, Sebastien Ibanez | <p>The evolution of mutualism between hosts and initially parasitic symbionts represents a major transition in evolution. Although vertical transmission of symbionts during host reproduction and partner control both favour the stability of mutuali... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Francois Massol | 2021-08-20 12:25:40 | View | |

23 Jan 2020

A novel workflow to improve multi-locus genotyping of wildlife species: an experimental set-up with a known model systemGillingham, Mark A. F., Montero, B. Karina, Wilhelm, Kerstin, Grudzus, Kara, Sommer, Simone and Santos, Pablo S. C. https://doi.org/10.1101/638288Improving the reliability of genotyping of multigene families in non-model organismsRecommended by François Rousset based on reviews by Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins, Helena Westerdahl and Thomas BigotThe reliability of published scientific papers has been the topic of much recent discussion, notably in the biomedical sciences [1]. Although small sample size is regularly pointed as one of the culprits, big data can also be a concern. The advent of high-throughput sequencing, and the processing of sequence data by opaque bioinformatics workflows, mean that sequences with often high error rates are produced, and that exact but slow analyses are not feasible. References [1] Ioannidis, J. P. A, Greenland, S., Hlatky, M. A., Khoury, M. J., Macleod, M. R., Moher, D., Schulz, K. F. and Tibshirani, R. (2014) Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. The Lancet, 383, 166-175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62227-8 | A novel workflow to improve multi-locus genotyping of wildlife species: an experimental set-up with a known model system | Gillingham, Mark A. F., Montero, B. Karina, Wilhelm, Kerstin, Grudzus, Kara, Sommer, Simone and Santos, Pablo S. C. | <p>Genotyping novel complex multigene systems is particularly challenging in non-model organisms. Target primers frequently amplify simultaneously multiple loci leading to high PCR and sequencing artefacts such as chimeras and allele amplification... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | François Rousset | Helena Westerdahl, Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins, Paul J. McMurdie , Arnaud Estoup, Vincent Segura, Jacek Radwan , Torbjørn Rognes , William Stutz , Kevin Vanneste , Thomas Bigot, Jill A. Hollenbach , Wieslaw Babik , Marie-Christin... | 2019-05-15 17:30:44 | View |

03 Oct 2023

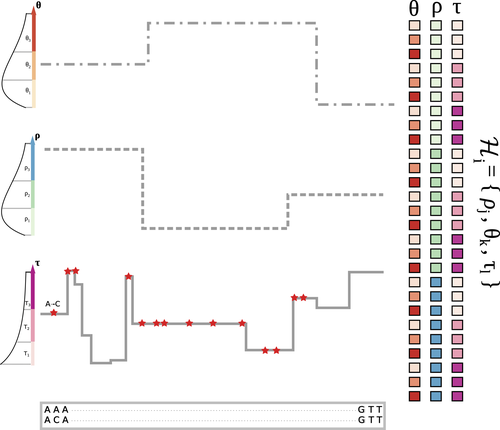

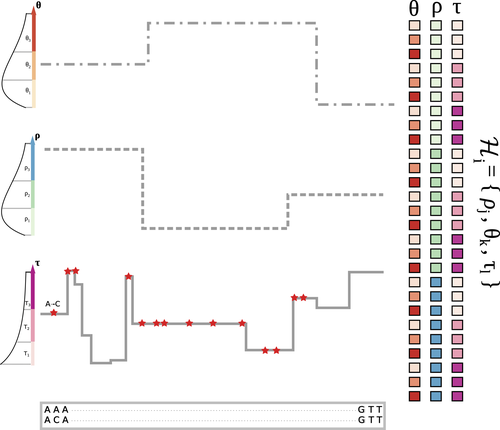

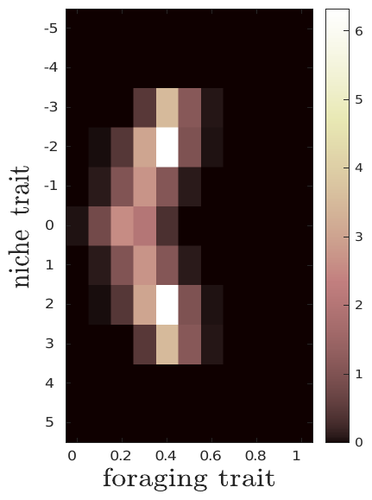

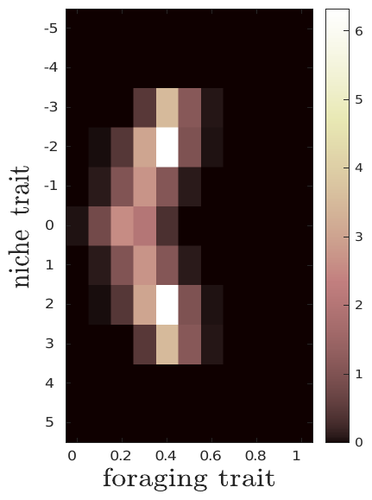

The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer modelLéo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Océane Guillot, Erwan Faou, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Ibanez https://doi.org/10.32942/X2QG7MEvolution and consequences of plastic foraging behavior in consumer-resource ecosystemsRecommended by François Rousset based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersPlastic responses of organisms to their environment may be maladaptive in particular when organisms are exposed to new environments. Phenotypic plasticity may also have opposite effects on the adaptive response of organisms to environmental changes: whether phenotypic plasticity favors or hinders such adaptation depends on a balance between the ability of the population to respond to the change non-genetically in the short term, and the weakened genetic response to environmental change. These topics have received continued attention, particularly in the context of climate change (e.g., Chevin et al. 2013, Duputié et al., 2015, Vinton et al . 2022). In their work, Ledru et al. focus on the adaptive nature of plastic behavior and on its consequences in a consumer-resource ecosystem. As they emphasize, previous works have found that plastic foraging promotes community stability, but these did not consider plasticity as an evolving trait, so Ledru et al. set out to test whether this conclusion holds when both plastic foraging and niche traits of consumers and resources evolve (though ultimately, their new conclusions may not all depend on plasticity evolving). Along the way, they first seek to clarify when such plasticity will evolve, and how it affects the evolution of the niche diversity of consumers and resources, before turning to the question of consumer persistence. The model is rather complex, as three traits are allowed to evolve, and the resource uptake expressed through plastic behavior has its own dynamics affected by some form of social learning. Classically, in models of niche evolution, a consumer's efficiency in exploiting a resource characterized by a trait y (here, the resource's individual niche trait), has been described in terms of location-scale (typically Gaussian) kernels, with mean x (the consumer's individual niche trait) specifying the most efficiently exploited resource, and with variance characterizing individual niche breadth. The evolution of the variance has been considered in some previous models but is assumed to be fixed here. Rather, the new model considers the evolution of the distribution of resource traits, of the consumer's individual niche trait (which is not plastic), and of a "plastic foraging trait" that controls the relative time spent foraging plastically versus foraging randomly. When foraging plastically, the consumers modify their foraging effort towards the type of resource that maximizes their energy intake. in some previous models, the effect of variation in the extent of plastic foraging was already considered, but the evolution of allocation to a plastic foraging strategy versus random foraging was not considered. The model is formulated through reaction-diffusion equations, and its dynamics is investigated by numerical integration. Foraging plasticity readily evolves, when resources vary widely enough, competition for resources is strong, and the cost of plasticity is weak. This means in particular that a large individual niche width of consumers selects for increased plastic foraging, as the evolution of plastic foraging leads to reduced niche overlap between consumers. The evolution of plastic foraging itself generally, though not always, favors the diversification of the niche traits of consumers and of resources. There is thus a positive feedback loop between plastic foraging and resource diversity. Ledru et al. conclude that the total niche width of the consumer population should also correlate with the evolution of plastic foraging, an implication which they relate to the so-called niche variation hypothesis and to empirical tests of it. The joint evolution of the consumer's individual niche trait and plastic foraging trait generates a striking pattern within populations: consumers whose individual niche trait is at an edge of the resource distribution forage more plastically. The authors observe that this relatively simple prediction has not been subjected to any empirical test. Returning to the question of consumer persistence, Ledru et al. evaluate this persistence when consumer mortality increases, and in response to either gradual or sudden environmental changes. These different perturbations all reduce the benefits of plastic foraging. The effect of plastic foraging on stability are complex, being negative or positive effect depending on the type of disturbance, and in particular the ecosystem has a lower sustainable rate of environmental change in the presence of plastic foraging. However, allowing the evolutionary regression of plastic foraging then has a comparatively positive effect on persistence. Despite the substantial effort devoted to analyzing this complex model, relaxing some of its assumptions would likely reveal further complexities. Notably, the overall effect of plasticity on consumer persistence depends on effects already encountered in models of the adaptive response of single species to environmental change: a fast non-genetic response in the short term versus a weakened genetic response in the longer term. The overall balance between these opposite effects on adaptation may be difficult to predict robustly. In the case of a constant rate of environmental change, the results of the present model depend on a lag load between the trait changes of consumer and resource populations, and the extent of the lag may also depend on many factors, such as the extent of genetic variation (e.g., Bürger & Lynch, 1995) for niche traits in consumers and resources. Here, the same variance of mutational effects was assumed for all three evolving traits. Further, spatial environmental variation, a central issue in studies of adaptive responses to environmental changes (e.g., Parmesan, 2006, Zhu et al., 2012), was not considered. Finally, the rate of adjustment of effort by consumers with given niche trait and plastic foraging trait values was assumed proportional to the density of consumers with such trait values. This was justified as a way of accounting for the use of social cues during foraging, but to the extent that they occur, social effects could manifest themselves through other learning dynamics. In conclusion, Ledru et al. have addressed a broad range of questions, suggesting new empirical tests of behavioural patterns on one side, and recovering in the context of community response to environmental changes a complexity that could be expected from earlier works on adaptive responses of organisms but that has been overlooked by previous works on community effects of phenotypic plasticity. References Bürger, R. and Lynch, M. (1995), Evolution and extinction in a changing environment: a quantitative-genetic analysis. Evolution, 49: 151-163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1995.tb05967.x Chevin, L.-M., Collins, S. and Lefèvre, F. (2013), Phenotypic plasticity and evolutionary demographic responses to climate change: taking theory out to the field. Funct Ecol, 27: 967-979. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02043.x Duputié, A., Rutschmann, A., Ronce, O. and Chuine, I. (2015), Phenological plasticity will not help all species adapt to climate change. Glob Change Biol, 21: 3062-3073. https://doi-org.inee.bib.cnrs.fr/10.1111/gcb.12914 Ledru, L., Garnier, J., Guillot, O., Faou, E., & Ibanez, S. (2023). The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer model. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2QG7M Parmesan, C. (2006) Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change Vinton, A.C., Gascoigne, S.J.L., Sepil, I., Salguero-Gómez, R., (2022) Plasticity’s role in adaptive evolution depends on environmental change components. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 37: 1067-1078. Zhu, K., Woodall, C.W. and Clark, J.S. (2012), Failure to migrate: lack of tree range expansion in response to climate change. Glob Change Biol, 18: 1042-1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02571.x | The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer model | Léo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Océane Guillot, Erwan Faou, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Ibanez | <p style="text-align: justify;">Phenotypic plasticity has important ecological and evolutionary consequences. In particular, behavioural phenotypic plasticity such as plastic foraging (PF) by consumers, may enhance community stability. Yet little ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | François Rousset | 2023-03-25 12:04:08 | View | |

04 Mar 2021

Simulation of bacterial populations with SLiMJean Cury, Benjamin C. Haller, Guillaume Achaz, and Flora Jay https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.28.316869Simulating bacterial evolution forward-in-timeRecommended by Frederic Bertels based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersJean Cury and colleagues (2021) have developed a protocol to simulate bacterial evolution in SLiM. In contrast to existing methods that depend on the coalescent, SLiM simulates evolution forward in time. SLiM has, up to now, mostly been used to simulate the evolution of eukaryotes (Haller and Messer 2019), but has been adapted here to simulate evolution in bacteria. Forward-in-time simulations are usually computationally very costly. To circumvent this issue, bacterial population sizes are scaled down. One would now expect results to become inaccurate, however, Cury et al. show that scaled-down forwards simulations provide very accurate results (similar to those provided by coalescent simulators) that are consistent with theoretical expectations. Simulations were analyzed and compared to existing methods in simple and slightly more complex scenarios where recombination affects evolution. In all scenarios, simulation results from coalescent methods (fastSimBac (De Maio and Wilson 2017), ms (Hudson 2002)) and scaled-down forwards simulations were very similar, which is very good news indeed. A biologist not aware of the complexities of forwards, backwards simulations and the coalescent, might now naïvely ask why another simulation method is needed if existing methods perform just as well. To address this question the manuscript closes with a very neat example of what exactly is possible with forwards simulations that cannot be achieved using existing methods. The situation modeled is the growth and evolution of a set of 50 bacteria that are randomly distributed on a petri dish. One side of the petri dish is covered in an antibiotic the other is antibiotic-free. Over time, the bacteria grow and acquire antibiotic resistance mutations until the entire artificial petri dish is covered with a bacterial lawn. This simulation demonstrates that it is possible to simulate extremely complex (e.g. real world) scenarios to, for example, assess whether certain phenomena are expected with our current understanding of bacterial evolution, or whether there are additional forces that need to be taken into account. Hence, forwards simulators could significantly help us to understand what current models can and cannot explain in evolutionary biology.

References Cury J, Haller BC, Achaz G, Jay F (2021) Simulation of bacterial populations with SLiM. bioRxiv, 2020.09.28.316869, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.28.316869 De Maio N, Wilson DJ (2017) The Bacterial Sequential Markov Coalescent. Genetics, 206, 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.116.198796 Haller BC, Messer PW (2019) SLiM 3: Forward Genetic Simulations Beyond the Wright–Fisher Model. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 36, 632–637. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy228 Hudson RR (2002) Generating samples under a Wright–Fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics, 18, 337–338. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/18.2.337 | Simulation of bacterial populations with SLiM | Jean Cury, Benjamin C. Haller, Guillaume Achaz, and Flora Jay | <p>Simulation of genomic data is a key tool in population genetics, yet, to date, there is no forward-in-time simulator of bacterial populations that is both computationally efficient and adaptable to a wide range of scenarios. Here we demonstrate... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics | Frederic Bertels | 2020-10-02 19:03:42 | View | |

29 Sep 2022

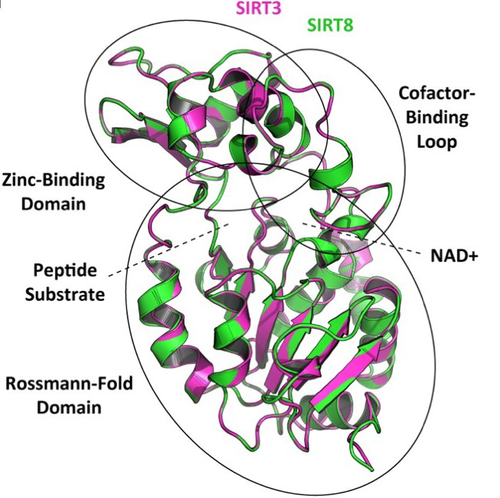

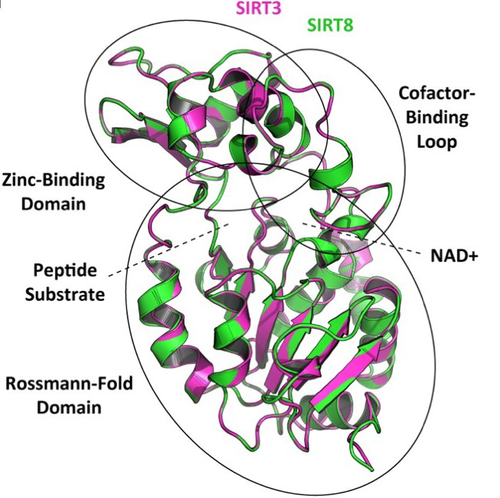

How many sirtuin genes are out there? evolution of sirtuin genes in vertebrates with a description of a new family memberJuan C. Opazo, Michael W. Vandewege, Federico G. Hoffmann, Kattina Zavala, Catalina Meléndez, Charlotte Luchsinger, Viviana A. Cavieres, Luis Vargas-Chacoff, Francisco J. Morera, Patricia V. Burgos, Cheril Tapia-Rojas, Gonzalo A. Mardones https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.17.209510Making sense of vertebrate sirtuin genesRecommended by Frédéric Delsuc based on reviews by Filipe Castro, Nicolas Leurs and 1 anonymous reviewerSirtuin proteins are class III histone deacetylases that are involved in a variety of fundamental biological functions mostly related to aging. These proteins are located in different subcellular compartments and are associated with different biological functions such as metabolic regulation, stress response, and cell cycle control [1]. In mammals, the sirtuin gene family is composed of seven paralogs (SIRT1-7) grouped into four classes [2]. Due to their involvement in maintaining cell cycle integrity, sirtuins have been studied as a way to understand fundamental mechanisms governing longevity [1]. Indeed, the downregulation of sirtuin genes with aging seems to explain much of the pathophysiology that accumulates with aging [3]. Biomedical studies have thus explored the potential therapeutic implications of sirtuins [4] but whether they can effectively be used as molecular targets for the treatment of human diseases remains to be demonstrated [1]. Despite this biomedical interest and some phylogenetic analyses of sirtuin paralogs mostly conducted in mammals, a comprehensive evolutionary analysis of the sirtuin gene family at the scale of vertebrates was still lacking. In this preprint, Opazo and collaborators [5] took advantage of the increasing availability of whole-genome sequences for species representing all main groups of vertebrates to unravel the evolution of the sirtuin gene family. To do so, they undertook a phylogenomic approach in its original sense aimed at improving functional predictions by evolutionary analysis [6] in order to inventory the full vertebrate sirtuin gene repertoire and reconstruct its precise duplication history. Harvesting genomic databases, they extracted all predicted sirtuin proteins and performed phylogenetic analyses based on probabilistic inference methods. Maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses resulted in well-resolved and congruent phylogenetic trees dividing vertebrate sirtuin genes into three major clades. These analyses also revealed an additional eighth paralog that was previously overlooked because of its restricted phyletic distribution. This newly identified sirtuin family member (named SIRT8) was recovered with unambiguous statistical support as a sister-group to the SIRT3 clade. Comparative genomic analyses based on conserved gene synteny confirmed that SIRT8 was present in all sampled non-amniote vertebrate genomes (cartilaginous fish, bony fish, coelacanth, lungfish, and amphibians) except cyclostomes. SIRT8 has thus most likely been lost in the last common ancestor of amniotes (mammals, reptiles, and birds). Discovery of such previously unknown genes in vertebrates is not completely surprising given the plethora of high-quality genomes now available. However, this study highlights the importance of considering a broad taxonomic sampling to infer evolutionary patterns of gene families that have been mostly studied in mammals because of their potential importance for human biology. Based on its phylogenetic position as closely related to SIRT3 within class I, it could be predicted that the newly identified SIRT8 paralog likely has a deacetylase activity and is probably located in mitochondria. To test these evolutionary predictions, Opazo and collaborators [5] conducted further bioinformatics analyses and functional experiments using the elephant shark (Callorhinchus milii) as a model species. RNAseq expression data were analyzed to determine tissue-specific transcription of sirtuin genes in vertebrates, including SIRT8 found to be mainly expressed in the ovary, which suggests a potential role in biological processes associated with reproduction. The elephant shark SIRT8 protein sequence was used with other vertebrates for comparative analyses of protein structure modeling and subcellular localization prediction both pointing to a probable mitochondrial localization. The protein localization and its function were further characterized by immunolocalization in transfected cells, and enzymatic and functional assays, which all confirmed the prediction that SIRT8 proteins are targeted to the mitochondria and have deacetylase activity. The extensive experimental efforts made in this study to shed light on the function of this newly discovered gene are both rare and highly commendable. Overall, this work by Opazo and collaborators [5] provides a comprehensive phylogenomic study of the sirtuin gene family in vertebrates based on detailed evolutionary analyses using state-of-the-art phylogenetic reconstruction methods. It also illustrates the power of adopting an integrative comparative approach supplementing the reconstruction of the duplication history of the gene family with complementary functional experiments in order to elucidate the function of the newly discovered SIRT8 family member. These results provide a reference phylogenetic framework for the evolution of sirtuin genes and the further functional characterization of the eight vertebrate paralogs with potential relevance for understanding the cellular biology of aging and its associated diseases in human. References [1] Vassilopoulos A, Fritz KS, Petersen DR, Gius D (2011) The human sirtuin family: Evolutionary divergences and functions. Human Genomics, 5, 485. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-7364-5-5-485 [2] Yamamoto H, Schoonjans K, Auwerx J (2007) Sirtuin Functions in Health and Disease. Molecular Endocrinology, 21, 1745–1755. https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2007-0079 [3] Morris BJ (2013) Seven sirtuins for seven deadly diseases ofaging. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 56, 133–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.10.525 [4] Bordo D Structure and Evolution of Human Sirtuins. Current Drug Targets, 14, 662–665. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1389450111314060007 [5] Opazo JC, Vandewege MW, Hoffmann FG, Zavala K, Meléndez C, Luchsinger C, Cavieres VA, Vargas-Chacoff L, Morera FJ, Burgos PV, Tapia-Rojas C, Mardones GA (2022) How many sirtuin genes are out there? evolution of sirtuin genes in vertebrates with a description of a new family member. bioRxiv, 2020.07.17.209510, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.17.209510 [6] Eisen JA (1998) Phylogenomics: Improving Functional Predictions for Uncharacterized Genes by Evolutionary Analysis. Genome Research, 8, 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.8.3.163 | How many sirtuin genes are out there? evolution of sirtuin genes in vertebrates with a description of a new family member | Juan C. Opazo, Michael W. Vandewege, Federico G. Hoffmann, Kattina Zavala, Catalina Meléndez, Charlotte Luchsinger, Viviana A. Cavieres, Luis Vargas-Chacoff, Francisco J. Morera, Patricia V. Burgos, Cheril Tapia-Rojas, Gonzalo A. Mardones | <p style="text-align: justify;">Studying the evolutionary history of gene families is a challenging and exciting task with a wide range of implications. In addition to exploring fundamental questions about the origin and evolution of genes, disent... |  | Molecular Evolution | Frédéric Delsuc | Filipe Castro, Anonymous, Nicolas Leurs | 2022-05-12 16:06:04 | View |

12 Apr 2017

POSTPRINT

Genetic drift, purifying selection and vector genotype shape dengue virus intra-host genetic diversity in mosquitoesLequime S, Fontaine A, Gouilh MA, Moltini-Conclois I and Lambrechts L https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006111Vectors as motors (of virus evolution)Recommended by Frédéric Fabre and Benoit MouryMany viruses are transmitted by biological vectors, i.e. organisms that transfer the virus from one host to another. Dengue virus (DENV) is one of them. Dengue is a mosquito-borne viral disease that has rapidly spread around the world since the 1940s. One recent estimate indicates 390 million dengue infections per year [1]. As many arthropod-borne vertebrate viruses, DENV has to cross several anatomical barriers in the vector, to multiply in its body and to invade its salivary glands before getting transmissible. As a consequence, vectors are not passive carriers but genuine hosts of the viruses that potentially have important effects on the composition of virus populations and, ultimately, on virus epidemiology and virulence. Within infected vectors, virus populations are expected to acquire new mutations and to undergo genetic drift and selection effects. However, the intensity of these evolutionary forces and the way they shape virus genetic diversity are poorly known. In their study, Lequime et al. [2] finely disentangled the effects of genetic drift and selection on DENV populations during their infectious cycle within mosquito (Aedes aegypti) vectors. They evidenced that the genetic diversity of viruses within their vectors is shaped by genetic drift, selection and vector genotype. The experimental design consisted in artificial acquisition of purified virus by mosquitoes during a blood meal. The authors monitored the diversity of DENV populations in Ae. aegypti individuals at different time points by high-throughput sequencing (HTS). They estimated the intensity of genetic drift and selection effects exerted on virus populations by comparing the DENV diversity at these sampling time points with the diversity in the purified virus stock (inoculum). Disentangling the effects of genetic drift and selection remains a methodological challenge because both evolutionary forces operate concomitantly and both reduce genetic diversity. However, selection reduces diversity in a reproducible manner among experimental replicates (here, mosquito individuals): the fittest variants are favoured at the expense of the weakest ones. In contrast, genetic drift reduces diversity in a stochastic manner among replicates. Genetic drift acts equally on all variants irrespectively of their fitness. The strength of genetic drift is frequently evaluated with the effective population size Ne: the lower Ne, the stronger the genetic drift [3]. The estimation of the effective population size of DENV populations by Lequime et al. [2] was based on single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were (i) present both in the inoculum and in the virus populations sampled at the different time points and (ii) that were neutral (or nearly-neutral) and therefore subjected to genetic drift only and insensitive to selection. As expected for viruses that possess small and constrained genomes, such neutral SNPs are extremely rare. Starting from a set of >1800 SNPs across the DENV genome, only three SNPs complied with the neutrality criteria and were enough represented in the sequence dataset for a precise Ne estimation. Using the method described by Monsion et al. [4], Lequime et al. [2] estimated Ne values ranging from 5 to 42 viral genomes (95% confidence intervals ranged from 2 to 161 founding viral genomes). Consequently, narrow bottlenecks occurred at the virus acquisition step, since the blood meal had allowed the ingestion of ca. 3000 infectious virus particles, on average. Interestingly, bottleneck sizes did not differ between mosquito genotypes. Monsion et al.’s [4] formula provides only an approximation of Ne. A corrected formula has been recently published [5]. We applied this exact Ne formula to the means and variances of the frequencies of the three neutral markers estimated before and after the bottlenecks (Table 1 in [2]), and nearly identical Ne estimates were obtained with both formulas. Selection intensity was estimated from the dN/dS ratio between the nonsynonymous and synonymous substitution rates using the HTS data on DENV populations. DENV genetic diversity increased following initial infection but was restricted by strong purifying selection during virus expansion in the midgut. Again, no differences were detected between mosquito genotypes. However and importantly, significant differences in DENV genetic diversity were detected among mosquito genotypes. As they could not be related to differences in initial genetic drift or to selection intensity, the authors raise interesting alternative hypotheses, including varying rates of de novo mutations due to differences in replicase fidelity or differences in the balancing selection regime. Interestingly, they also suggest that this observation could simply result from a methodological issue linked to the detection threshold of low-frequency SNPs. References [1] Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, et al. 2013. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496: 504–7 doi: 10.1038/nature12060 [2] Lequime S, Fontaine A, Gouilh MA, Moltini-Conclois I and Lambrechts L. 2016. Genetic drift, purifying selection and vector genotype shape dengue virus intra-host genetic diversity in mosquitoes. PloS Genetics 12: e1006111 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006111 [3] Charlesworth B. 2009. Effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation. Nature Reviews Genetics 10: 195-205 doi: 10.1038/nrg2526 [4] Monsion B, Froissart R, Michalakis Y and Blanc S. 2008. Large bottleneck size in cauliflower mosaic virus populations during host plant colonization. PloS Pathogens 4: e1000174 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000174 [5] Thébaud G and Michalakis Y. 2016. Comment on ‘Large bottleneck size in cauliflower mosaic virus populations during host plant colonization’ by Monsion et al. (2008). PloS Pathogens 12: e1005512 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005512 | Genetic drift, purifying selection and vector genotype shape dengue virus intra-host genetic diversity in mosquitoes | Lequime S, Fontaine A, Gouilh MA, Moltini-Conclois I and Lambrechts L | Due to their error-prone replication, RNA viruses typically exist as a diverse population of closely related genomes, which is considered critical for their fitness and adaptive potential. Intra-host demographic fluctuations that stochastically re... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Frédéric Fabre | 2017-04-10 14:26:04 | View | |

09 Dec 2019

Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasitesEva JP Lievens, Yannis Michalakis, Thomas Lenormand https://doi.org/10.1101/621581Trade-offs in fitness components and ecological source-sink dynamics affect host specialisation in two parasites of Artemia shrimpsRecommended by Frédéric Guillaume based on reviews by Anne Duplouy, Seth Barribeau and Cindy Gidoin based on reviews by Anne Duplouy, Seth Barribeau and Cindy Gidoin

Ecological specialisation, especially among parasites infecting a set of host species, is ubiquitous in nature. Host specialisation can be understood as resulting from trade-offs in parasite infectivity, virulence and growth. However, it is not well understood how variation in these trade-offs shapes the overall fitness trade-off a parasite faces when adapting to multiple hosts. For instance, it is not clear whether a strong trade-off in one fitness component may sufficiently constrain the evolution of a generalist parasite despite weak trade-offs in other components. A second mechanism explaining variation in specialisation among species is habitat availability and quality. Rare habitats or habitats that act as ecological sinks will not allow a species to persist and adapt, preventing a generalist phenotype to evolve. Understanding the prevalence of those mechanisms in natural systems is crucial to understand the emergence and maintenance of host specialisation, and biodiversity in general. References [1] Lievens, E.J.P., Michalakis, Y. and Lenormand, T. (2019). Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasites. bioRxiv, 621581, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/621581 | Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasites | Eva JP Lievens, Yannis Michalakis, Thomas Lenormand | <p>The evolution of host specialization has been studied intensively, yet it is still often difficult to determine why parasites do not evolve broader niches – in particular when the available hosts are closely related and ecologically similar. He... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Experimental Evolution, Life History, Species interactions | Frédéric Guillaume | 2019-05-13 13:44:34 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer