Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors▼ | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

24 Oct 2019

Testing host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects : a phylogenetic perspectiveEmmanuelle Jousselin, Marianne Elias https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.09510v1Phylogenetic approaches for reconstructing macroevolutionary scenarios of phytophagous insect diversificationRecommended by Hervé Sauquet based on reviews by Brian O'Meara and 1 anonymous reviewerPlant-animal interactions have long been identified as a major driving force in evolution. However, only in the last two decades have rigorous macroevolutionary studies of the topic been made possible, thanks to the increasing availability of densely sampled molecular phylogenies and the substantial development of comparative methods. In this extensive and thoughtful perspective [1], Jousselin and Elias thoroughly review current hypotheses, data, and available macroevolutionary methods to understand how plant-insect interactions may have shaped the diversification of phytophagous insects. First, the authors review three main hypotheses that have been proposed to lead to host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects: the ‘escape and radiate’, ‘oscillation’, and ‘musical chairs’ scenarios, each with their own set of predictions. Jousselin and Elias then synthesize a vast core of recent studies on different clades of insects, where explicit phylogenetic approaches have been used. In doing so, they highlight heterogeneity in both the methods being used and predictions being tested across these studies and warn against the risk of subjective interpretation of the results. Lastly, they advocate for standardization of phylogenetic approaches and propose a series of simple tests for the predictions of host-driven speciation scenarios, including the characterization of host-plant range history and host breadth history, and diversification rate analyses. This helpful review will likely become a new point of reference in the field and undoubtedly help many researchers formalize and frame questions of plant-insect diversification in future studies of phytophagous insects. References [1] Jousselin, E., Elias, M. (2019). Testing Host-Plant Driven Speciation in Phytophagous Insects: A Phylogenetic Perspective. arXiv, 1910.09510, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.09510v1 | Testing host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects : a phylogenetic perspective | Emmanuelle Jousselin, Marianne Elias | During the last two decades, ecological speciation has been a major research theme in evolutionary biology. Ecological speciation occurs when reproductive isolation between populations evolves as a result of niche differentiation. Phytophagous ins... |  | Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Speciation, Species interactions | Hervé Sauquet | 2019-02-25 17:31:33 | View | |

29 Jul 2020

POSTPRINT

The Y chromosome may contribute to sex-specific ageing in DrosophilaEmily J Brown, Alison H Nguyen, Doris Bachtrog https://doi.org/10.1101/156042Y chromosome makes fruit flies die youngerRecommended by Gabriel Marais, Jean-François Lemaitre and Cristina VieiraIn most animal species, males and females display distinct survival prospect, a phenomenon known as sex gap in longevity (SGL, Marais et al. 2018). The study of SGLs is crucial not only for having a full picture of the causes underlying organisms’ health, aging and death but also to initiate the development of sex-specific anti-aging interventions in humans (Austad and Bartke 2015). Three non-mutually evolutionary causes have been proposed to underlie SGLs (Marais et al. 2018). First, SGLs could be the consequences of sex-differences in life history strategies. For example, evolving dimorphic traits (e.g. body size, ornaments or armaments) may imply unequal physiological costs (e.g. developmental, maintenance) between the sexes and this may result in differences in longevity and aging. Second, mitochondria are usually transmitted by the mother and thus selection is blind to mitochondrial deleterious mutations affecting only males. Such mutations can freely accumulate in the mitochondrial genome and may reduce male longevity, a phenomenon called the mother’s curse (Frank and Hurst 1996). Third, in species with sex chromosomes, all recessive deleterious mutations will be expressed on the single X chromosome in XY males and may reduce their longevity (the unguarded X effect). In addition, the numerous transposable elements (TEs) on the Y chromosome may affect aging. TE activity is normally repressed by epigenetic regulation (DNA methylation, histone modifications and small RNAs). However, it is known that this regulation is disrupted with increasing age. Because of the TE-rich Y chromosome, more TEs may become active in old males than in old females, generating more somatic mutations, accelerating aging and reducing longevity in males (the toxic Y effect, Marais et al. 2018). References Austad, S. N., and Bartke, A. (2015). Sex differences in longevity and in responses to anti-aging interventions: A Mini-Review. Gerontology, 62(1), 40–46. 10.1159/000381472 | The Y chromosome may contribute to sex-specific ageing in Drosophila | Emily J Brown, Alison H Nguyen, Doris Bachtrog | <p>Heterochromatin suppresses repetitive DNA, and a loss of heterochromatin has been observed in aged cells of several species, including humans and *Drosophila*. Males often contain substantially more heterochromatic DNA than females, due to the ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Expression Studies, Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Gabriel Marais | 2020-07-28 15:06:18 | View | |

18 Jan 2023

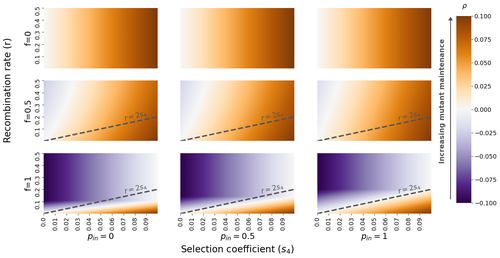

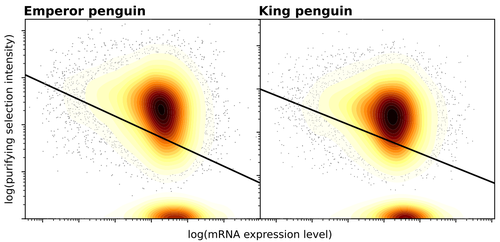

The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfingEmilie Tezenas, Tatiana Giraud, Amandine Veber, Sylvain Billiard https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.07.511119Maintenance of deleterious mutations and recombination suppression near mating-type loci under selfingRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe causes and consequences of the evolution of sexual reproduction are a major topic in evolutionary biology. With advances in sequencing technology, it becomes possible to compare sexual chromosomes across species and infer the neutral and selective processes shaping polymorphism at these chromosomes. Most sex and mating-type chromosomes exhibit an absence of recombination in large genomic regions around the animal, plant or fungal sex-determining genes. This suppression of recombination likely occurred in several time steps generating stepwise increasing genomic regions starting around the sex-determining genes. This mechanism generates so-called evolutionary strata of differentiation between sex chromosomes (Nicolas et al., 2004, Bergero and Charlesworth, 2009, Hartmann et al. 2021). The evolution of extended regions of recombination suppression is also documented on mating-type chromosomes in fungi (Hartmann et al., 2021) and around supergenes (Yan et al., 2020, Jay et al., 2021). The exact reason and evolutionary mechanisms for this phenomenon are still, however, debated. Two hypotheses are proposed: 1) sexual antagonism (Charlesworth et al., 2005), which, nevertheless, does explain the observed occurrence of the evolutionary strata, and 2) the sheltering of deleterious alleles by inversions carrying a lower load than average in the population (Charlesworth and Wall, 1999, Antonovics and Abrams, 2004). In the latter, the mechanism is as follows. A genetic inversion or a suppressor of recombination in cis may exhibit some overdominance behaviour. The inversion exhibiting less recessive deleterious mutations (compared to others at the same locus) may increase in frequency, before at higher frequency occurring at the homozygous state, expressing its genetic load. However, the inversion may never be at the homozygous state if it is genetically linked to a gene in a permanently heterozygous state. The inversion can then be advantageous and may reach fixation at the sex chromosome (Charlesworth and Wall, 1999, Antonovics and Abrams, 2004, Jay et al., 2022). These selective mechanisms promote thus the suppression of recombination around the sex-determining gene, and recessive deleterious mutations are permanently sheltered. This hypothesis is corroborated by the sheltering of deleterious mutations observed around loci under balancing selection (Llaurens et al. 2009, Lenz et al. 2016) and around mating-type genes in fungi and supergenes (Jay et al. 2021, Jay et al., 2022). In this present theoretical study, Tezenas et al. (2022) analyse how linkage to a necessarily heterozygous fungal mating type locus influences the persistence/extinction time of a new mutation at a second selected locus. This mutation can either be deleterious and recessive, or overdominant. There is arbitrary linkage between the two loci, and sexual reproduction occurs either between 1) gametes of different individuals (outcrossing), or 2) by selfing with gametes originating from the same (intra-tetrad) or different (inter-tetrad) tetrads produced by that individual. Note, here, that the mating-type gene does not prevent selfing. The authors study the initial stochastic dynamics of the mutation using a multi-type branching process (and simulations when analytical results cannot be obtained) to compute the extinction time of the deleterious mutation. The main result is that the presence of a mating-type locus always decreases the purging probability and increases the purging time of the mutations under selfing. Ultimately, deleterious mutations can indeed accumulate near the mating-type locus over evolutionary time scales. In a nutshell, high selfing or high intra-tetrad mating do increase the sheltering effect of the mating-type locus. In effect, the outcome of sheltering of deleterious mutations depends on two opposing mechanisms: 1) a higher selfing rate induces a greater production of homozygotes and an increased effect of the purging of deleterious mutations, while 2) a higher intra-tetrad selfing rate (or linkage with the mating-type locus) generates heterozygotes which have a small genetic load (and are favoured). The authors also show that rare events of extremely long maintenance of deleterious mutations can occur. The authors conclude by highlighting the manifold effect of selfing which reduces the effective population size and thus impairs the efficiency of selection and increases the mutational load, while also favouring the purge of deleterious homozygous mutations. Furthermore, this study emphasizes the importance of studying the maintenance and accumulation of deleterious mutations in the vicinity of heterozygous loci (e.g. under balancing selection) in selfing species. References Antonovics J, Abrams JY (2004) Intratetrad Mating and the Evolution of Linkage Relationships. Evolution, 58, 702–709. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00403.x Bergero R, Charlesworth D (2009) The evolution of restricted recombination in sex chromosomes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 24, 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.09.010 Charlesworth D, Morgan MT, Charlesworth B (1990) Inbreeding Depression, Genetic Load, and the Evolution of Outcrossing Rates in a Multilocus System with No Linkage. Evolution, 44, 1469–1489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb03839.x Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B, Marais G (2005) Steps in the evolution of heteromorphic sex chromosomes. Heredity, 95, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800697 Charlesworth B, Wall JD (1999) Inbreeding, heterozygote advantage and the evolution of neo–X and neo–Y sex chromosomes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 266, 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1999.0603 Hartmann FE, Duhamel M, Carpentier F, Hood ME, Foulongne-Oriol M, Silar P, Malagnac F, Grognet P, Giraud T (2021) Recombination suppression and evolutionary strata around mating-type loci in fungi: documenting patterns and understanding evolutionary and mechanistic causes. New Phytologist, 229, 2470–2491. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17039 Jay P, Chouteau M, Whibley A, Bastide H, Parrinello H, Llaurens V, Joron M (2021) Mutation load at a mimicry supergene sheds new light on the evolution of inversion polymorphisms. Nature Genetics, 53, 288–293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-00771-1 Jay P, Tezenas E, Véber A, Giraud T (2022) Sheltering of deleterious mutations explains the stepwise extension of recombination suppression on sex chromosomes and other supergenes. PLOS Biology, 20, e3001698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001698 Lenz TL, Spirin V, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR (2016) Excess of Deleterious Mutations around HLA Genes Reveals Evolutionary Cost of Balancing Selection. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 33, 2555–2564. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw127 Llaurens V, Gonthier L, Billiard S (2009) The Sheltered Genetic Load Linked to the S Locus in Plants: New Insights From Theoretical and Empirical Approaches in Sporophytic Self-Incompatibility. Genetics, 183, 1105–1118. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.109.102707 Nicolas M, Marais G, Hykelova V, Janousek B, Laporte V, Vyskot B, Mouchiroud D, Negrutiu I, Charlesworth D, Monéger F (2004) A Gradual Process of Recombination Restriction in the Evolutionary History of the Sex Chromosomes in Dioecious Plants. PLOS Biology, 3, e4. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0030004 Tezenas E, Giraud T, Véber A, Billiard S (2022) The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfing. bioRxiv, 2022.10.07.511119, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.07.511119 Yan Z, Martin SH, Gotzek D, Arsenault SV, Duchen P, Helleu Q, Riba-Grognuz O, Hunt BG, Salamin N, Shoemaker D, Ross KG, Keller L (2020) Evolution of a supergene that regulates a trans-species social polymorphism. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 240–249. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-1081-1 | The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfing | Emilie Tezenas, Tatiana Giraud, Amandine Veber, Sylvain Billiard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Large regions of suppressed recombination having extended over time occur in many organisms around genes involved in mating compatibility (sex-determining or mating-type genes). The sheltering of deleterious alleles... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Aurelien Tellier | 2022-10-10 13:50:30 | View | |

28 Mar 2024

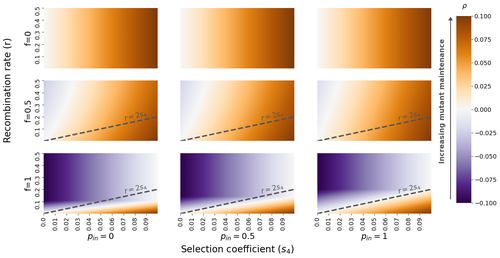

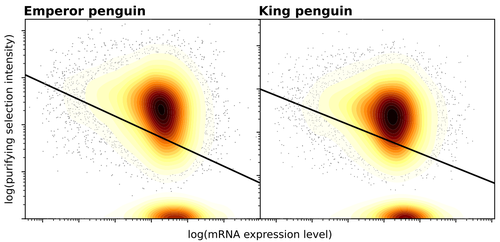

Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populationsEmiliano Trucchi, Piergiorgio Massa, Francesco Giannelli, Thibault Latrille, Flavia A.N. Fernandes, Lorena Ancona, Nils Chr Stenseth, Joan Ferrer Obiol, Josephine Paris, Giorgio Bertorelle, Celine Le Bohec https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552445Purifying selection on highly expressed genes in PenguinsRecommended by Bruce Rannala based on reviews by Tanja Pyhäjärvi and 1 anonymous reviewerGiven the general importance of protein expression levels, in cells it is widely accepted that gene expression levels are often a target of natural selection and that most mutations affecting gene expression levels are therefore likely to be deleterious [1]. However, it is perhaps less obvious that the strength of selection on the regulated genes themselves may be influenced by their expression levels. This might be due to harmful effects of misfolded proteins, for example, when higher protein concentrations exist in cells [2]. Recent studies have suggested that highly expressed genes accumulate fewer deleterious mutations; thus a positive relationship appears to exist between gene expression levels and the relative strength of purifying selection [3]. The recommended paper by Trucchi et al. [4] examines the relationship between gene expression, purifying selection and a third variable -- effective population size -- in populations of two species of penguin with different population sizes, the Emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) and the King penguin (A. patagonicus). Using transcriptomic data and computer simulations modeling selection, they examine patterns of nonsynonymous and synonymous segregating polymorphisms (p) across genes in the two populations, concluding that even in relatively small populations purifying selection has an important effect in eliminating deleterious mutations. References 1] Gilad Y, Oshlack A, and Rifkin SA. 2006. Natural selection on gene expression. Trends in Genetics 22: 456-461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.002 [4] Trucchi E, Massa P, Giannelli F, Latrille T, Fernandes FAN, Ancona L, Stenseth NC, Obiol JF, Paris J, Bertorelle G, and Le Bohec, C. 2023. Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populations. bioRxiv 2023.08.08.552445, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552445

| Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populations | Emiliano Trucchi, Piergiorgio Massa, Francesco Giannelli, Thibault Latrille, Flavia A.N. Fernandes, Lorena Ancona, Nils Chr Stenseth, Joan Ferrer Obiol, Josephine Paris, Giorgio Bertorelle, Celine Le Bohec | <p style="text-align: justify;">Purifying selection is the most pervasive type of selection, as it constantly removes deleterious mutations arising in populations, directly scaling with population size. Highly expressed genes appear to accumulate ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Bruce Rannala | 2023-08-09 17:53:03 | View | |

05 Dec 2017

Reconstruction of body mass evolution in the Cetartiodactyla and mammals using phylogenomic dataEmeric Figuet, Marion Ballenghien, Nicolas Lartillot, Nicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/139147Predicting small ancestors using contemporary genomes of large mammalsRecommended by Bruce Rannala based on reviews by Bruce Rannala and 1 anonymous reviewerRecent methodological developments and increased genome sequencing efforts have introduced the tantalizing possibility of inferring ancestral phenotypes using DNA from contemporary species. One intriguing application of this idea is to exploit the apparent correlation between substitution rates and body size to infer ancestral species' body sizes using the inferred patterns of substitution rate variation among species lineages based on genomes of extant species [1]. References [1] Romiguier J, Ranwez V, Douzery EJP and Galtier N. 2013. Genomic evidence for large, long-lived ancestors to placental mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 5–13. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss211 [2] Figuet E, Ballenghien M, Lartillot N and Galtier N. 2017. Reconstruction of body mass evolution in the Cetartiodactyla and mammals using phylogenomic data. bioRxiv, ver. 3 of 4th December 2017. 139147. doi: 10.1101/139147 | Reconstruction of body mass evolution in the Cetartiodactyla and mammals using phylogenomic data | Emeric Figuet, Marion Ballenghien, Nicolas Lartillot, Nicolas Galtier | <p>Reconstructing ancestral characters on a phylogeny is an arduous task because the observed states at the tips of the tree correspond to a single realization of the underlying evolutionary process. Recently, it was proposed that ancestral traits... |  | Genome Evolution, Life History, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Bruce Rannala | 2017-05-18 15:28:58 | View | |

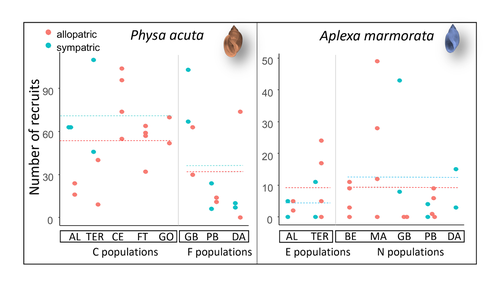

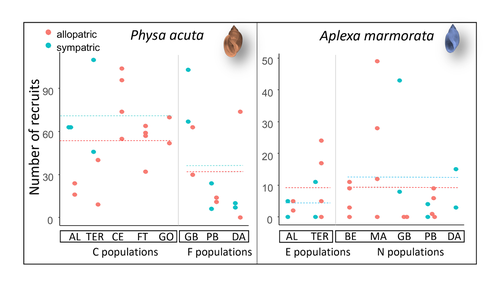

01 Mar 2024

Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident speciesElodie Chapuis, Philippe Jarne, Patrice David https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.25.563987The evolution of a hobo snailRecommended by Ben Phillips based on reviews by David Reznick and 2 anonymous reviewersAt the very end of a paper entitled "Copepodology for the ornithologist" Hutchinson (1951) pointed out the possibility of 'fugitive species'. A fugitive species, said Hutchinson, is one that we would typically think of as competitively inferior. Wherever it happens to live it will eventually be overwhelmed by competition from another species. We would expect it to rapidly go extinct but for one reason: it happens to be a much better coloniser than the other species. Now all we need to explain its persistence is a dose of space and a little disturbance: a world in which there are occasional disturbances that cause local extinction of the dominant species. Now, argued Hutchinson, we have a recipe for persistence, albeit of a harried kind. As Hutchinson put it, fugitive species "are forever on the move, always becoming extinct in one locality as they succumb to competition, and always surviving as they reestablish themselves in some other locality." It is a fascinating idea, not just because it points to an interesting strategy, but also because it enriches our idea of competition: competition for space can be just as important as competition for time. Hutchinson's idea was independently discovered with the advent of metapopulation theory (Levins 1971; Slatkin 1974) and since then, of course, ecologists have gone looking, and they have unearthed many examples of species that could be said to have a fugitive lifestyle. These fugitive species are out there, but we don't often get to see them evolve. In their recent paper, Chapuis et al. (2024) make a convincing case that they have seen the evolution of a fugitive species. They catalog the arrival of an invasive freshwater snail on Guadeloupe in the Lesser Antilles, and they wonder what impact this snail's arrival might have on a native freshwater snail. This is a snail invasion, so it has been proceeding at a majestic pace, allowing the researchers to compare populations of the native snail that are completely naive to the invader with those that have been exposed to the invader for either a relatively short period (<20 generations) or longer periods (>20 generations). They undertook an extensive set of competition assays on these snails to find out which species were competitively superior and how the native species' competitive ability has evolved over time. Against naive populations of the native, the invasive snail turns out to be unequivocally the stronger competitor. (This makes sense; it probably wouldn't have been able to invade if it wasn't.) So what about populations of the native snail that have been exposed for longer, that have had time to adapt? Surprisingly these populations appear to have evolved to become even weaker competitors than they already were. So why is it that the native species has not simply been driven extinct? Drawing on their previous work on this system, the authors can explain this situation. The native species appears to be the better coloniser of new habitats. Thus, it appears that the arrival of the invasive species has pushed the native species into a different place along the competition-colonisation axis. It has sacrificed competitive ability in favour of becoming a better coloniser; it has become a fugitive species in its own backyard. This is a really nice empirical study. It is a large lab study, but one that makes careful sampling around a dynamic field situation. Thus, it is a lab study that informs an earlier body of fieldwork and so reveals a fascinating story about what is happening in the field. We are left not only with a particularly compelling example of character displacement towards a colonising phenotype but also with something a little less scientific: the image of a hobo snail, forever on the run, surviving in the spaces in between. References Chapuis E, Jarne P, David P (2024) Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident species. bioRxiv, 2023.10.25.563987, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.25.563987 Hutchinson, G.E. (1951) Copepodology for the Ornithologist. Ecology 32: 571–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/1931746 Levins, R., and D. Culver. (1971) Regional Coexistence of Species and Competition between Rare Species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 68, no. 6: 1246–48. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.68.6.1246. Slatkin, Montgomery. (1974) Competition and Regional Coexistence. Ecology 55, no. 1: 128–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1934625. | Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident species | Elodie Chapuis, Philippe Jarne, Patrice David | <p style="text-align: justify;">Biological invasions by phylogenetically and ecologically similar competitors pose an evolutionary challenge to native species. Cases of character displacement following invasions suggest that they can respond to th... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Species interactions | Ben Phillips | 2023-10-26 15:49:33 | View | |

14 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

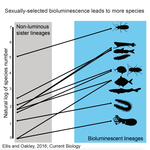

High Rates of Species Accumulation in Animals with Bioluminescent Courtship DisplaysEllis EA, Oakley TH 10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.043Bioluminescent sexually selected traits as an engine for biodiversity across animal speciesRecommended by Astrid Groot and Carole SmadjaIn evolutionary biology, sexual selection is hypothesized to increase speciation rates in animals, as theory predicts that sexual selection will contribute to phenotypic diversification and affect rates of species accumulation at macro-evolutionary time scales. However, testing this hypothesis and gathering convincing evidence have proven difficult. Although some studies have shown a strong correlation between proxies of sexual selection and species diversity (mostly in birds), this relationship relies on some assumptions on the link between these proxies and the strength of sexual selection and is not detected in some other taxa, making taxonomically widespread conclusions impossible. In a recent study published in Current Biology [1], Ellis and Oakley provide strong evidence that bioluminescent sexual displays have driven high species richness in taxonomically diverse animal lineages, providing a crucial link between sexual selection and speciation. Ellis and Oakley [1] explored the scientific literature for well-resolved evolutionary trees with branches containing bioluminescent lineages and identified lineages that use light for courtship or camouflage in a wide range of marine and terrestrial taxa including insects, crustaceans, cephalopods, segmented worms, and fishes. The researchers counted the number of species in each bioluminescent clade and found that all groups with light-courtship displays had more species and faster rates of species accumulation than their non-luminous most closely related sister lineages or ancestors. In contrast, those groups that used bioluminescence for predator avoidance had a lower than expected rate of species richness on average. Nicely encompassing a diversity of taxa and neatly controlling for the rate of species accumulation of the encompassing clade, the results of Ellis and Oakley are clear-cut and provide the most comprehensive evidence to date for the hypothesis that sexual displays can act as drivers of speciation. One question this study incites is what is happening in terms of sexual selection in species displaying defensive bioluminescence or no bioluminescence at all: do those lineages use no mating signals at all or other mating signals that are less apparent, and will those experience lower levels of sexual selection than bioluminescent mating signals, i.e. consistent with Ellis and Oakley results? It would also be interesting to investigate the diversification rates in animal species using other modalities, such as chemical, acoustic or any other type of signals used by males, females or both sexes, to determine what types of sexual signals may be more generally drivers of speciation. References [1] Ellis EA, Oakley TH. 2016. High Rates of Species Accumulation in Animals with Bioluminescent Courtship Displays. Current Biology 26:1916–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.043 [2] Davis MP, Holcroft NI, Wiley EO, Sparks JS, Smith WL. 2014. Species-specific bioluminescence facilitates speciation in the deep sea. Marine Biology 161:11391148. doi: 10.1007/s00227-014-2406-x [3] Davis MP, Sparks JS, Smith WL. 2016. Repeated and Widespread Evolution of Bioluminescence in Marine Fishes. PLoS One 11:e0155154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155154 [4] Claes JM, Nilsson D-E, Mallefet J, Straube N. 2015. The presence of lateral photophores correlates with increased speciation in deep-sea bioluminescent sharks. Royal Society Open Science 2:150219. doi: 10.1098/rsos.150219 | High Rates of Species Accumulation in Animals with Bioluminescent Courtship Displays | Ellis EA, Oakley TH | One of the great mysteries of evolutionary biology is why closely related lineages accumulate species at different rates. Theory predicts that populations undergoing strong sexual selection will more quickly differentiate because of increased pote... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Sexual Selection, Speciation | Astrid Groot | 2016-12-14 19:01:59 | View | |

21 Nov 2022

Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughsElisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard https://doi.org/10.1101/679472The variety of bread-making practices promotes diversity conservation in food microbial communitiesRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Jeanne Ropars based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersDomesticated organisms are excellent models for understanding ecology and evolution and they are important for our food production and safety. While less studied than plants and animals, micro-organisms have also been domesticated, in particular for food fermentation [1]. The most studied domesticated micro-organism is the yeast used to make wine, beer and bread, Saccharomyces cerevisiae [2, 3, 4]. Filamentous fungi used for cheese-making have recently gained interest, for example Penicillium roqueforti used to make blue cheeses and P. camemberti to make soft cheeses [5, 6, 7, 8]. As for plants and animals, domestication has led to beneficial traits for food production in fermenting fungi, but also to bottlenecks and degeneration [6, 7, 9]; P. camemberti for example does not produce enough spores any more for optimal culture and inoculation and P. roqueforti has lost sexual fertility [9]. The loss of genetic diversity and of species diversity in our food production system is concerning for multiple reasons : i) it jeopardizes future improvement in the face of global changes ; ii) it causes the loss of evolved diversity during centuries under human selection, and therefore of beneficial characteristics and specificities that we may never be able to recover ; iii) it leads to degeneration in the few cultivated strains; iv) it impoverishes the diversity of our food products and local adaptation of production practices. The study of domesticated fungi used for food fermentation has focused so far on the evolution of lineages and on their metabolic specificities. Microbiological assemblages and species diversity have been much less studied, while they likely also have a strong impact on the quality and safety of final products. This study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] addresses this question, using an interdisciplinary participatory research approach including bakers, psycho-sociologists and microbiologists to analyse bread-making practices and their impact on microbial communities in sourdough. Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] identified two distinct groups of bread-making practices based on interviews and surveys, with farmer-like practices (low bread production, use of ancient wheat populations, manual kneading, working at ambient temperature, long fermentation periods and no use of commercial baker’s yeast) versus more intensive, artisanal-like practices. Metabarcoding and microbial culture-based analyses showed that the well-known baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was, surprisingly, not the most common species in French organic sourdoughs. Kazachstania was the most represented yeast genus over all sourdoughs, both in terms of read abundance and of species diversity. Kazachstania species were also often dominant in individual sourdoughs, but Saccharomyces uvarum or Torulaspora delbrueckii could also be the dominant yeast species. Metabarcoding analyses further revealed that the composition of the fungal communities differed between the farmer-like and more intensive practices, representing the first evidence of the influence of artisanal practices on microbial communities. The fungal communities were impacted by a combination of bread-making variables including the type of wheat varieties, the length of fermentation, the quantity of bread made per week and the use of commercial yeast. Maintaining on farm less intensive bread-making practices, may allow the preservation of typical species and phenotypic diversity in microbial communities in sourdough. Farmer-like practices did not lead to higher diversity within sourdoughs but, overall, the diversity of bread-making practices allow maintaining a larger diversity in sourdoughs. For example, different Kazachstania species were most abundant in sourdoughs from artisanal-like and farmer-like practices. Interviews with the bakers suggested the role of dispersal of Kazachstania species in shaping sourdough microbial communities, dispersal occurring by seed exchanges, sourdough mixing or gifts, bread-making training in common or working in one another’s bakery. Nikolai Vavilov [11] had already highlighted for crops the importance of isolated cultures and selection in different farms for generating and preserving crop diversity, but also the importance of seed exchange for fostering adaptation. Furthermore, one of the yeast frequently found in artisanal sourdoughs, Kazachstania humilis, displayed phenotypic differences between sourdough and non-sourdough strains, suggesting domestication. The sourdough strains exhibited significantly higher CO2 production rate and a lower fermentation latency-phase time. The study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] is thus novel and inspiring in showing the importance of interdisciplinary studies, combining metabarcoding, microbiology and interviews for assessing the composition and diversity of microbial communities in human-made food, and in revealing the impact of artisanal-like bread-making practices in preserving microbial community diversity. Interdisciplinary studies are still rare but have already shown the importance of combining ethno-ecology, biology and evolution to decipher the role of human practices on genetic diversity in crops, animals and food microorganisms and to help preserving genetic resources [12]. For example, in the case of the bread wheat Triticum aestivum, such interdisciplinary studies have shown that genetic diversity has been shaped by farmers’ seed diffusion and farming practices [13]. We need more of such interdisciplinary studies on the impact of farmer versus industrial agricultural and food-making practices as we urgently need to preserve the diversity of micro-organisms used in food production that we are losing at a rapid pace [6, 7, 14]. References [1] Dupont J, Dequin S, Giraud T, Le Tacon F, Marsit S, Ropars J, Richard F, Selosse M-A (2017) Fungi as a Source of Food. Microbiology Spectrum, 5, 5.3.09. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0030-2016 [2] Legras J-L, Galeote V, Bigey F, Camarasa C, Marsit S, Nidelet T, Sanchez I, Couloux A, Guy J, Franco-Duarte R, Marcet-Houben M, Gabaldon T, Schuller D, Sampaio JP, Dequin S (2018) Adaptation of S. cerevisiae to Fermented Food Environments Reveals Remarkable Genome Plasticity and the Footprints of Domestication. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1712–1727. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy066 [3] Bai F-Y, Han D-Y, Duan S-F, Wang Q-M (2022) The Ecology and Evolution of the Baker’s Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes, 13, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13020230 [4] Fay JC, Benavides JA (2005) Evidence for Domesticated and Wild Populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLOS Genetics, 1, e5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0010005 [5] Ropars J, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, López-Villavicencio M, Gouzy J, Sallet E, Dumas É, Lacoste S, Debuchy R, Dupont J, Branca A, Giraud T (2015) Adaptive Horizontal Gene Transfers between Multiple Cheese-Associated Fungi. Current Biology, 25, 2562–2569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.025 [6] Dumas E, Feurtey A, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Le Prieur S, Snirc A, Coton M, Thierry A, Coton E, Le Piver M, Roueyre D, Ropars J, Branca A, Giraud T (2020) Independent domestication events in the blue-cheese fungus Penicillium roqueforti. Molecular Ecology, 29, 2639–2660. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15359 [7] Ropars J, Didiot E, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Bennetot B, Coton M, Poirier E, Coton E, Snirc A, Le Prieur S, Giraud T (2020) Domestication of the Emblematic White Cheese-Making Fungus Penicillium camemberti and Its Diversification into Two Varieties. Current Biology, 30, 4441-4453.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.082 [8] Caron T, Piver ML, Péron A-C, Lieben P, Lavigne R, Brunel S, Roueyre D, Place M, Bonnarme P, Giraud T, Branca A, Landaud S, Chassard C (2021) Strong effect of Penicillium roqueforti populations on volatile and metabolic compounds responsible for aromas, flavor and texture in blue cheeses. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 354, 109174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109174 [9] Ropars J, Lo Y-C, Dumas E, Snirc A, Begerow D, Rollnik T, Lacoste S, Dupont J, Giraud T, López-Villavicencio M (2016) Fertility depression among cheese-making Penicillium roqueforti strains suggests degeneration during domestication. Evolution, 70, 2099–2109. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13015 [10] Michel E, Masson E, Bubbendorf S, Lapicque L, Nidelet T, Segond D, Guézenec S, Marlin T, Devillers H, Rué O, Onno B, Legrand J, Sicard D, Bakers TP (2022) Artisanal and farmer bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs. bioRxiv, 679472, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/679472 [11] Vavilov NI, Vavylov MI, Dorofeev VF (1992) Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants. Cambridge University Press. [12] Saslis-Lagoudakis CH, Clarke AC (2013) Ethnobiology: the missing link in ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28, 67–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.10.017 [13] Thomas M, Demeulenaere E, Dawson JC, Khan AR, Galic N, Jouanne-Pin S, Remoue C, Bonneuil C, Goldringer I (2012) On-farm dynamic management of genetic diversity: the impact of seed diffusions and seed saving practices on a population-variety of bread wheat. Evolutionary Applications, 5, 779–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-4571.2012.00257.x [14] Demeulenaere É, Lagrola M (2021) Des indicateurs pour accompagner “ les éleveurs de microbes” : Une communauté épistémique face au problème des laits “ paucimicrobiens ” dans la production fromagère au lait cru (1995-2015). Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances, 15. http://journals.openedition.org/rac/24953 | Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs | Elisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Preserving microbial diversity in food systems is one of the many challenges to be met to achieve food security and quality. Although industrialization led to the selection and spread of specific fermenting microbia... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology | Tatiana Giraud | 2022-01-27 14:53:08 | View | |

07 Jul 2017

Unmasking the delusive appearance of negative frequency-dependent selectionRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by David Baltrus and 2 anonymous reviewersExplaining the processes that maintain polymorphisms in a population has been a fundamental line of research in evolutionary biology. One of the main mechanisms identified that preserves genetic diversity is negative frequency-dependent selection (NFDS), which constitutes a powerful framework for interpreting the presence of persistent polymorphisms. Nevertheless, a number of patterns that are often explained by invoking NFDS may also be compatible with, and possibly more easily explained by, different processes. References [1] Brisson D. 2017. Negative frequency-dependent selection is frequently confounding. bioRxiv 113324, ver. 3 of 20th June 2017. doi: 10.1101/113324 [2] Heino M, Metz JAJ and Kaitala V. 1998. The enigma of frequency-dependent selection. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 13: 367-370. doi: 1016/S0169-5347(98)01380-9 | Negative frequency-dependent selection is frequently confounding | Dustin Brisson | The existence of persistent genetic variation within natural populations presents an evolutionary problem as natural selection and genetic drift tend to erode genetic diversity. Models of balancing selection were developed to account for the high ... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Ignacio Bravo | 2017-03-03 18:46:42 | View | |

06 Oct 2022

Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch.Duneau, David; Moest, Markus; Ebert, Dieter https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929414Evolution of sperm morphology in Daphnia within a phyologenetic contextRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Renate Matzke-Karasz and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this study sperm morphology is studied in 15 Daphnia species and the morphological data are mapped on a Daphnia phylogeny. The authors found that despite the internal fertilization mode, Daphnia have among the smallest sperm recorded, as would be expected with external fertilization. The authors also conclude that increase in sperm length has evolved twice, that sperm encapsulation has been lost in a clade, and that this clade has very polymorphic sperm with long, and often numerous, filopodia. Daphnia is an interesting model to study sperm morphology because the biology of sexual reproduction is often ignored in (cyclical) parthenogenetic species. Daphnia is part of the very diverse and successful group of cladocerans with cyclical parthenogenetic reproduction. The success of this reproduction mode is reflected in the known 620 species that radiated within this order, this is more than half of the known Branchiopod species diversity and the estimated number of cladoceran species is even two to four times higher (Forró et al. 2008). Looking at this particular model with a good phylogeny and some particularity in the mode of fertilization/reproduction, has thus a large value. Most Daphnia species are cyclical parthenogenetic and switch between sexual and asexual reproduction depending on the environmental conditions. Within the genus Daphnia, evolution to obligate asexuality has evolved in at least four independent occasions by three different mechanisms: (i) obligate parthenogenesis through hybridisation with or without polyploidy, (ii) asexuality has been acquired de novo in some populations and (iii) in certain lineages females reproduce by obligate parthenogenesis, whereas the clonally propagated males produce functional haploid sperm that allows them to breed with sexual females of normal cyclically parthenogenetic lineages (more on this in Decaestecker et al. 2009). This study is made in the context of a body of research on the evolution of one of the most fundamental and taxonomically diverse cell types. There is surprisingly little known about the adaptive value underlying their morphology because it is very difficult to test this experimentally. Studying sperm morphology across species is interesting to study evolution itself because it is a "simple trait". As the authors state: The understanding of the adaptive value of sperm morphology, such as length and shape, remains largely incomplete (Lüpold & Pitnick, 2018). Based on phylogenetic analyses across the animal kingdom, the general rule seems to be that fertilization mode (i.e. whether eggs are fertilized within or outside the female) is a key predictor of sperm length (Kahrl et al., 2021). There is a trade-off between sperm number and length (Immler et al., 2011). This study reports on one of the smallest sperm recorded despite the fertilization being internal. The brood pouch in Daphnia is an interesting particularity as fertilisation occurs internally, but it is not disconnected from the environment. It is also remarkable that there are two independent evolution lines of sperm size in this group. It suggests that those traits have an adaptive value. References Decaestecker E, De Meester L, Mergeay J (2009) Cyclical Parthenogenesis in Daphnia: Sexual Versus Asexual Reproduction. In: Lost Sex: The Evolutionary Biology of Parthenogenesis (eds Schön I, Martens K, Dijk P), pp. 295–316. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2770-2_15 Duneau David, Möst M, Ebert D (2022) Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. bioRxiv, 2020.01.31.929414, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929414 Forró L, Korovchinsky NM, Kotov AA, Petrusek A (2008) Global diversity of cladocerans (Cladocera; Crustacea) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia, 595, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-007-9013-5 Immler S, Pitnick S, Parker GA, Durrant KL, Lüpold S, Calhim S, Birkhead TR (2011) Resolving variation in the reproductive tradeoff between sperm size and number. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 5325–5330. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1009059108 Kahrl AF, Snook RR, Fitzpatrick JL (2021) Fertilization mode drives sperm length evolution across the animal tree of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5, 1153–1164. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01488-y Lüpold S, Pitnick S (2018) Sperm form and function: what do we know about the role of sexual selection? Reproduction, 155, R229–R243. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-17-0536 | Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. | Duneau, David; Moest, Markus; Ebert, Dieter | <p style="text-align: justify;">Sperm is the most fundamental male reproductive feature. It serves the fertilization of eggs and evolves under sexual selection. Two components of sperm are of particular interest, their number and their morphology.... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Morphological Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-05-30 22:54:15 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer