Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▼ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

26 Aug 2021

Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durabilityMéline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112Durability of plant resistance to diploid pathogenRecommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Loup Rimbaud and 1 anonymous reviewerDurability of plant resistance to diploid pathogen Hirohisa Kishino Based on the population genetic and epidemiologic model, Saubin et al. (2021) report that the resistant hosts generated by the breeding based on the gene-for-gene interaction is durable much longer against diploid pathogens than haploid pathogens. The avr allele of pathogen that confers the resistance is genetically recessive. The heterozygotes are not recognized by the resistant hosts and only the avr/avr homozygote is adaptive. As a result, the trajectory of avr allele frequency becomes more stochastic due to genetic drift. Although the paper focuses on the evolution of standing polymorphism, it seems obvious that the adaptive mutations in pathogen have much larger probability of being deleted from the population because the individuals own the avr allele mostly in the form of heterozygote at the initial phase after the mutation. Since only few among many models of plant resistance deployment study the case of diploid pathogen and the contribution of the pathogen life cycle, this work will add an important intellect to the literature (Rimbaud et al. 2021). From the study of host-parasite interaction in flax rust Melampsora lini, Flor (1942, 1955) showed that the host resistance is formed by the interaction of a host resistance gene and a corresponding pathogen gene. This gene-for-gene hypothesis has been supported by experimental evidence and has served as a basis of the methods of molecular breeding targeting the dominant R genes. However, modern agriculture provides the pathogen populations with the homogeneous environments and laid strong selection pressure on them. As a result, the newly developed resistant plants face the risk of immediate resistance breakdown (Möller and Stukenbrock 2017). Currently, quantitative resistance is getting attention as characters as a potential target for long-life (mild) resistant breeds (Lannou, 2012). They are polygenic and controlled partly by the same genes that mediate qualitative resistance but mostly by the genes that encode defense-related outputs such as strengthening of the cell wall or defense compound biosynthesis (Corwin and Kliebenstein, 2017). Progress of molecular genetics may overcome the technical difficulty (Bakkeren and Szabo, 2020). Saubin et al. (2021) notes that the pattern of genetic inheritance of the pathogen counterparts that respond to the host traits is crucial regarding with the durability of the resistant hosts. The resistance traits for which avr alleles are predicted to be recessive may be the targets of breeding. References Bakkeren, G., and Szabo, L. J. (2020) Progress on molecular genetics and manipulation of rust fungi. Phytopathology, 110, 532-543. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-07-19-0228-IA Corwin, J. A., and Kliebenstein, D. J. (2017) Quantitative resistance: more than just perception of a pathogen. The Plant Cell, 29, 655-665. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.16.00915 Flor, H. H. (1942) Inheritance of pathogenicity in a cross between physiological races 22 and 24 of Melampsova lini. Phytopathology, 35. Abstract. Flor, H. H. (1955) Host-parasite interactions in flax rust-its genetics and other implications. Phytopathology, 45, 680-685. Lannou, C. (2012) Variation and selection of quantitative traits in plant pathogens. Annual review of phytopathology, 50, 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-173031 Möller, M. and Stukenbrock, E. H. (2017) Evolution and genome architecture in fungal plant pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 15, 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.76 Rimbaud, L., Fabre, F., Papaïx, J., Moury, B., Lannou, C., Barrett, L. G., and Thrall, P. H. (2021) Models of Plant Resistance Deployment. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 59. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-020620-122134 Saubin, M., De Mita, S., Zhu, X., Sudret, B. and Halkett, F. (2021) Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability. bioRxiv, 2021.05.28.446112, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112 | Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability | Méline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett | <p>The breeding of resistant hosts based on the gene-for-gene interaction is crucial to address epidemics of plant pathogens in agroecosystems. Resistant host deployment strategies are developed and studied worldwide to decrease the probability of... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Hirohisa Kishino | 2021-06-03 07:58:16 | View | |

29 Sep 2017

Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of the South American continentMichael D. Pirie, Paul J. M. Maas, Rutger A. Wilschut, Heleen Melchers-Sharrott & Lars W. Chatrou 10.1101/141127Unravelling the history of Neotropical plant diversificationRecommended by Hervé Sauquet based on reviews by Thomas Couvreur and Hervé SauquetSouth American rainforests, particularly the Tropical Andes, have been recognized as the hottest spot of plant biodiversity on Earth, while facing unprecedented threats from human impact [1,2]. Considerable research efforts have recently focused on unravelling the complex geological, bioclimatic, and biogeographic history of the region [3,4]. While many studies have addressed the question of Neotropical plant diversification using parametric methods to reconstruct ancestral areas and patterns of dispersal, Pirie et al. [5] take a distinct, complementary approach. Based on a new, near-complete molecular phylogeny of two Neotropical genera of the flowering plant family Annonaceae, the authors modelled the ecological niche of each species and reconstructed the history of niche differentiation across the region. The main conclusion is that, despite similar current distributions and close phylogenetic distance, the two genera experienced rather distinct processes of diversification, responding differently to the major geological events marking the history of the region in the last 20 million years (Andean uplift, drainage of Lake Pebas, and closure of the Panama Isthmus). As a researcher who has not personally worked on Neotropical biogeography, I found this paper captivating and especially enjoyed very much reading the Introduction, which sets out the questions very clearly. The strength of this paper is the near-complete diversity of species the authors were able to sample in each clade and the high-quality data compiled for the niche models. I would recommend this paper as a nice example of a phylogenetic study aimed at unravelling the detailed history of Neotropical plant diversification. While large, synthetic meta-analyses of many clades should continue to seek general patterns [4,6], careful studies restricted on smaller, but well controlled and sampled datasets such as this one are essential to really understand tropical plant diversification in all its complexity. References [1] Antonelli A, and Sanmartín I. 2011. Why are there so many plant species in the Neotropics? Taxon 60, 403–414. [2] Mittermeier RA, Robles-Gil P, Hoffmann M, Pilgrim JD, Brooks TB, Mittermeier CG, Lamoreux JL and Fonseca GAB. 2004. Hotspots revisited: Earths biologically richest and most endangered ecoregions. CEMEX, Mexico City, Mexico 390pp [3] Antonelli A, Nylander JAA, Persson C and Sanmartín I. 2009. Tracing the impact of the Andean uplift on Neotropical plant evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA 106, 9749–9754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811421106 [4] Hoorn C, Wesselingh FP, ter Steege H, Bermudez MA, Mora A, Sevink J, Sanmartín I, Sanchez-Meseguer A, Anderson CL, Figueiredo JP, Jaramillo C, Riff D, Negri FR, Hooghiemstra H, Lundberg J, Stadler T, Särkinen T and Antonelli A. 2010. Amazonia through time: Andean uplift, climate change, landscape evolution, and biodiversity. Science 330, 927–931. doi: 10.1126/science.1194585 [5] Pirie MD, Maas PJM, Wilschut R, Melchers-Sharrott H and Chatrou L. 2017. Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of the South American continent. bioRxiv, 141127, ver. 3 of 28th Sept 2017. doi: 10.1101/141127 [6] Bacon CD, Silvestro D, Jaramillo C, Tilston Smith B, Chakrabartye P and Antonelli A. 2015. Biological evidence supports an early and complex emergence of the Isthmus of Panama. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA 112, 6110–6115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423853112 | Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of the South American continent | Michael D. Pirie, Paul J. M. Maas, Rutger A. Wilschut, Heleen Melchers-Sharrott & Lars W. Chatrou | Much of the immense present day biological diversity of Neotropical rainforests originated from the Miocene onwards, a period of geological and ecological upheaval in South America. We assess the impact of the Andean orogeny, drainage of lake Peba... |  | Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Hervé Sauquet | Hervé Sauquet, Thomas Couvreur | 2017-06-03 21:25:48 | View |

24 Oct 2019

Testing host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects : a phylogenetic perspectiveEmmanuelle Jousselin, Marianne Elias https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.09510v1Phylogenetic approaches for reconstructing macroevolutionary scenarios of phytophagous insect diversificationRecommended by Hervé Sauquet based on reviews by Brian O'Meara and 1 anonymous reviewerPlant-animal interactions have long been identified as a major driving force in evolution. However, only in the last two decades have rigorous macroevolutionary studies of the topic been made possible, thanks to the increasing availability of densely sampled molecular phylogenies and the substantial development of comparative methods. In this extensive and thoughtful perspective [1], Jousselin and Elias thoroughly review current hypotheses, data, and available macroevolutionary methods to understand how plant-insect interactions may have shaped the diversification of phytophagous insects. First, the authors review three main hypotheses that have been proposed to lead to host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects: the ‘escape and radiate’, ‘oscillation’, and ‘musical chairs’ scenarios, each with their own set of predictions. Jousselin and Elias then synthesize a vast core of recent studies on different clades of insects, where explicit phylogenetic approaches have been used. In doing so, they highlight heterogeneity in both the methods being used and predictions being tested across these studies and warn against the risk of subjective interpretation of the results. Lastly, they advocate for standardization of phylogenetic approaches and propose a series of simple tests for the predictions of host-driven speciation scenarios, including the characterization of host-plant range history and host breadth history, and diversification rate analyses. This helpful review will likely become a new point of reference in the field and undoubtedly help many researchers formalize and frame questions of plant-insect diversification in future studies of phytophagous insects. References [1] Jousselin, E., Elias, M. (2019). Testing Host-Plant Driven Speciation in Phytophagous Insects: A Phylogenetic Perspective. arXiv, 1910.09510, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.09510v1 | Testing host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects : a phylogenetic perspective | Emmanuelle Jousselin, Marianne Elias | During the last two decades, ecological speciation has been a major research theme in evolutionary biology. Ecological speciation occurs when reproductive isolation between populations evolves as a result of niche differentiation. Phytophagous ins... |  | Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Speciation, Species interactions | Hervé Sauquet | 2019-02-25 17:31:33 | View | |

21 Nov 2018

Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infectionFrederic Bertels, Karin J Metzner, Roland R Regoes https://doi.org/10.1101/168260Is convergence an evidence for positive selection?Recommended by Guillaume Achaz based on reviews by Jeffrey Townsend and 1 anonymous reviewerThe preprint by Bertels et al. [1] reports an interesting application of the well-accepted idea that positively selected traits (here variants) can appear several times independently; think about the textbook examples of flight capacity. Hence, the authors assume that reciprocally convergence implies positive selection. The methodology becomes then, in principle, straightforward as one can simply count variants in independent datasets to detect convergent mutations. References [1] Bertels, F., Metzner, K. J., & Regoes R. R. (2018). Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infection. BioRxiv, 168260, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/168260 | Convergent evolution as an indicator for selection during acute HIV-1 infection | Frederic Bertels, Karin J Metzner, Roland R Regoes | <p>Convergent evolution describes the process of different populations acquiring similar phenotypes or genotypes. Complex organisms with large genomes only rarely and only under very strong selection converge to the same genotype. In contrast, ind... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Guillaume Achaz | 2017-07-26 08:39:17 | View | |

13 Dec 2018

Separate the wheat from the chaff: genomic analysis of local adaptation in the red coral Corallium rubrumPratlong M, Haguenauer A, Brener K, Mitta G, Toulza E, Garrabou J, Bensoussan N, Pontarotti P, Aurelle D https://doi.org/10.1101/306456Pros and Cons of local adaptation scansRecommended by Guillaume Achaz based on reviews by Lucas Gonçalves da Silva and 1 anonymous reviewerThe preprint by Pratlong et al. [1] is a well thought quest for genomic regions involved in local adaptation to depth in a species a red coral living the Mediterranean Sea. It first describes a pattern of structuration and then attempts to find candidate genes involved in local adaptation by contrasting deep with shallow populations. Although the pattern of structuration is clear and meaningful, the candidate genomic regions involved in local adaptation remain to be confirmed. Two external reviewers and myself found this preprint particularly interesting regarding the right-mindedness of the authors in front of the difficulties they encounter during their experiments. The discussions on the pros and cons of the approach are very sound and can be easily exported to a large number of studies that hunt for local adaptation. In this sense, the lessons one can learn by reading this well documented manuscript are certainly valuable for a wide range of evolutionary biologists. References [1] Pratlong, M., Haguenauer, A., Brener, K., Mitta, G., Toulza, E., Garrabou, J., Bensoussan, N., Pontarotti P., & Aurelle, D. (2018). Separate the wheat from the chaff: genomic scan for local adaptation in the red coral Corallium rubrum. bioRxiv, 306456, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/306456 | Separate the wheat from the chaff: genomic analysis of local adaptation in the red coral Corallium rubrum | Pratlong M, Haguenauer A, Brener K, Mitta G, Toulza E, Garrabou J, Bensoussan N, Pontarotti P, Aurelle D | <p>Genomic data allow an in-depth and renewed study of local adaptation. The red coral (Corallium rubrum, Cnidaria) is a highly genetically structured species and a promising model for the study of adaptive processes along an environmental gradien... |  | Adaptation, Population Genetics / Genomics | Guillaume Achaz | 2018-04-24 11:27:40 | View | |

18 Jun 2020

Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in betweenFanny Pouyet and Kimberly J. Gilbert http://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11490Molecular evolution through the joint lens of genomic and population processes.Recommended by Guillaume Achaz based on reviews by Benoit Nabholz and 1 anonymous reviewerIn their perspective article, F Pouyet and KJ Gilbert (2020), propose an interesting overview of all the processes that sculpt patterns of molecular evolution. This well documented article covers most (if not all) important facets of the recurrent debate that has marked the history of molecular evolution: the relative importance of natural selection and neutral processes (i.e. genetic drift). I particularly enjoyed reading this review, that instead of taking a clear position on the debate, catalogs patiently every pieces of information that can help understand how patterns we observed at the genome level, can be understood from a selectionnist point of view, from a neutralist one, and, to quote their title, from "everything in between". The review covers the classical objects of interest in population genetics (genetic drift, selection, demography and structure) but also describes several genomic processes (meiotic drive, linked selection, gene conversion and mutation processes) that obscure the interpretation of these population processes. The interplay between all these processes is very complex (to say the least) and have resulted in many cases in profound confusions while analyzing data. It is always very hard to fully acknowledge our ignorance and we have many times payed the price of model misspecifications. This review has the grand merit to improve our awareness in many directions. Being able to cover so many aspects of a wide topic, while expressing them simply and clearly, connecting concepts and observations from distant fields, is an amazing "tour de force". I believe this article constitutes an excellent up-to-date introduction to the questions and problems at stake in the field of molecular evolution and will certainly also help established researchers by providing them a stimulating overview supported with many relevant references. References [1] Pouyet F, Gilbert KJ (2020) Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between. arXiv:1909.11490 [q-bio]. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. url:https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11490 | Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between | Fanny Pouyet and Kimberly J. Gilbert | <p>A major goal of molecular evolutionary biology is to identify loci or regions of the genome under selection versus those evolving in a neutral manner. Correct identification allows accurate inference of the evolutionary process and thus compreh... |  | Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Guillaume Achaz | 2019-09-26 10:58:10 | View | |

28 Aug 2019

Is adaptation limited by mutation? A timescale-dependent effect of genetic diversity on the adaptive substitution rate in animalsMarjolaine Rousselle, Paul Simion, Marie-Ka Tilak, Emeric Figuet, Benoit Nabholz, Nicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/643619To tinker, evolution needs a supply of spare partsRecommended by Georgii Bazykin based on reviews by Konstantin Popadin, David Enard and 1 anonymous reviewerIs evolution adaptive? Not if there is no variation for natural selection to work with. Theory predicts that how fast a population can adapt to a new environment can be limited by the supply of new mutations coming into it. This supply, in turn, depends on two things: how often mutations occur and in how many individuals. If there are few mutations, or few individuals in whom they can originate, individuals will be mostly identical in their DNA, and natural selection will be impotent. References [1] G, J. A., Visser, M. de, Zeyl, C. W., Gerrish, P. J., Blanchard, J. L., and Lenski, R. E. (1999). Diminishing Returns from Mutation Supply Rate in Asexual Populations. Science, 283(5400), 404–406. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.404 | Is adaptation limited by mutation? A timescale-dependent effect of genetic diversity on the adaptive substitution rate in animals | Marjolaine Rousselle, Paul Simion, Marie-Ka Tilak, Emeric Figuet, Benoit Nabholz, Nicolas Galtier | <p>Whether adaptation is limited by the beneficial mutation supply is a long-standing question of evolutionary genetics, which is more generally related to the determination of the adaptive substitution rate and its relationship with the effective... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Georgii Bazykin | 2019-05-21 09:49:16 | View | |

24 Jan 2017

POSTPRINT

Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genomeSébastien Leclercq, Julien Thézé, Mohamed Amine Chebbi, Isabelle Giraud, Bouziane Moumen, Lise Ernenwein, Pierre Grève, Clément Gilbert, and Richard Cordaux 10.1073/pnas.1608979113A newly evolved W(olbachia) sex chromosome in pillbug!Recommended by Gabriel Marais and Sylvain CharlatIn some taxa such as fish and arthropods, closely related species can have different mechanisms of sex determination and in particular different sex chromosomes, which implies that new sex chromosomes are constantly evolving [1]. Several models have been developed to explain this pattern but empirical data are lacking and the causes of the fast sex chromosome turn over remain mysterious [2-4]. Leclerq et al. [5] in a paper that just came out in PNAS have focused on one possible explanation: Wolbachia. This widespread intracellular symbiont of arthropods can manipulate its host reproduction in a number of ways, often by biasing the allocation of resources toward females, the transmitting sex. Perhaps the most spectacular example is seen in pillbugs, where Wolbachia commonly turns infected males into females, thus doubling its effective transmission to grandchildren. Extensive investigations on this phenomenon were initiated 30 years ago in the host species Armadillidium vulgare. The recent paper by Leclerq et al. beautifully validates an hypothesis formulated in these pioneer studies [6], namely, that a nuclear insertion of the Wolbachia genome caused the emergence of new female determining chromosome, that is, a new sex chromosome. Many populations of A. vulgare are infected by the feminising Wolbachia strain wVulC, where the spread of the bacterium has also induced the loss of the ancestral female determining W chromosome (because feminized ZZ individuals produce females without transmitting any W). In these populations, all individuals carry two Z chromosomes, so that the bacterium is effectively the new sex-determining factor: specimens that received Wolbachia from their mother become females, while the occasional loss of Wolbachia from mothers to eggs allows the production of males. Intriguingly, studies from natural populations also report that some females are devoid both of Wolbachia and the ancestral W chromosome, suggesting the existence of new female determining nuclear factor, the hypothetical “f element”. Leclerq et al. [5] found the f element and decrypted its origin. By sequencing the genome of a strain carrying the putative f element, they found that a nearly complete wVulC genome got inserted in the nuclear genome and that the chromosome carrying the insertion has effectively become a new W chromosome. The insertion is indeed found only in females, PCRs and pedigree analysis tell. Although the Wolbachia-derived gene(s) that became sex-determining gene(s) remain to be identified among many possible candidates, the genomic and genetic evidence are clear that this Wolbachia insertion is determining sex in this pillbug strain. Leclerq et al. [5] also found that although this insertion is quite recent, many structural changes (rearrangements, duplications) have occurred compared to the wVulC genome, which study will probably help understand which bacterial gene(s) have retained a function in the nucleus of the pillbug. Also, in the future, it will be interesting to understand how and why exactly the nuclear inserted Wolbachia rose in frequency in the pillbug population and how the cytoplasmic Wolbachia was lost, and to tease apart the roles of selection and drift in this event. We highly recommend this paper, which provides clear evidence that Wolbachia has caused sex chromosome turn over in one species, opening the conjecture that it might have done so in many others. References [1] Bachtrog D, Mank JE, Peichel CL, Kirkpatrick M, Otto SP, Ashman TL, Hahn MW, Kitano J, Mayrose I, Ming R, Perrin N, Ross L, Valenzuela N, Vamosi JC. 2014. Tree of Sex Consortium. Sex determination: why so many ways of doing it? PLoS Biology 12: e1001899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001899 [2] van Doorn GS, Kirkpatrick M. 2007. Turnover of sex chromosomes induced by sexual conflict. Nature 449: 909-912. doi: 10.1038/nature06178 [3] Cordaux R, Bouchon D, Grève P. 2011. The impact of endosymbionts on the evolution of host sex-determination mechanisms. Trends in Genetics 27: 332-341. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.002 [4] Blaser O, Neuenschwander S, Perrin N. 2014. Sex-chromosome turnovers: the hot-potato model. American Naturalist 183: 140-146. doi: 10.1086/674026 [5] Leclercq S, Thézé J, Chebbi MA, Giraud I, Moumen B, Ernenwein L, Grève P, Gilbert C, Cordaux R. 2016. Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genome. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 113: 15036-15041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608979113 [6] Legrand JJ, Juchault P. 1984. Nouvelles données sur le déterminisme génétique et épigénétique de la monogénie chez le crustacé isopode terrestre Armadillidium vulgare Latr. Génétique Sélection Evolution 16: 57–84. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-16-1-57 | Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genome | Sébastien Leclercq, Julien Thézé, Mohamed Amine Chebbi, Isabelle Giraud, Bouziane Moumen, Lise Ernenwein, Pierre Grève, Clément Gilbert, and Richard Cordaux | Sex determination is an evolutionarily ancient, key developmental pathway governing sexual differentiation in animals. Sex determination systems are remarkably variable between species or groups of species, however, and the evolutionary forces und... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Gabriel Marais | 2017-01-13 15:15:51 | View | |

29 Jul 2020

POSTPRINT

The Y chromosome may contribute to sex-specific ageing in DrosophilaEmily J Brown, Alison H Nguyen, Doris Bachtrog https://doi.org/10.1101/156042Y chromosome makes fruit flies die youngerRecommended by Gabriel Marais, Jean-François Lemaitre and Cristina VieiraIn most animal species, males and females display distinct survival prospect, a phenomenon known as sex gap in longevity (SGL, Marais et al. 2018). The study of SGLs is crucial not only for having a full picture of the causes underlying organisms’ health, aging and death but also to initiate the development of sex-specific anti-aging interventions in humans (Austad and Bartke 2015). Three non-mutually evolutionary causes have been proposed to underlie SGLs (Marais et al. 2018). First, SGLs could be the consequences of sex-differences in life history strategies. For example, evolving dimorphic traits (e.g. body size, ornaments or armaments) may imply unequal physiological costs (e.g. developmental, maintenance) between the sexes and this may result in differences in longevity and aging. Second, mitochondria are usually transmitted by the mother and thus selection is blind to mitochondrial deleterious mutations affecting only males. Such mutations can freely accumulate in the mitochondrial genome and may reduce male longevity, a phenomenon called the mother’s curse (Frank and Hurst 1996). Third, in species with sex chromosomes, all recessive deleterious mutations will be expressed on the single X chromosome in XY males and may reduce their longevity (the unguarded X effect). In addition, the numerous transposable elements (TEs) on the Y chromosome may affect aging. TE activity is normally repressed by epigenetic regulation (DNA methylation, histone modifications and small RNAs). However, it is known that this regulation is disrupted with increasing age. Because of the TE-rich Y chromosome, more TEs may become active in old males than in old females, generating more somatic mutations, accelerating aging and reducing longevity in males (the toxic Y effect, Marais et al. 2018). References Austad, S. N., and Bartke, A. (2015). Sex differences in longevity and in responses to anti-aging interventions: A Mini-Review. Gerontology, 62(1), 40–46. 10.1159/000381472 | The Y chromosome may contribute to sex-specific ageing in Drosophila | Emily J Brown, Alison H Nguyen, Doris Bachtrog | <p>Heterochromatin suppresses repetitive DNA, and a loss of heterochromatin has been observed in aged cells of several species, including humans and *Drosophila*. Males often contain substantially more heterochromatic DNA than females, due to the ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Expression Studies, Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Gabriel Marais | 2020-07-28 15:06:18 | View | |

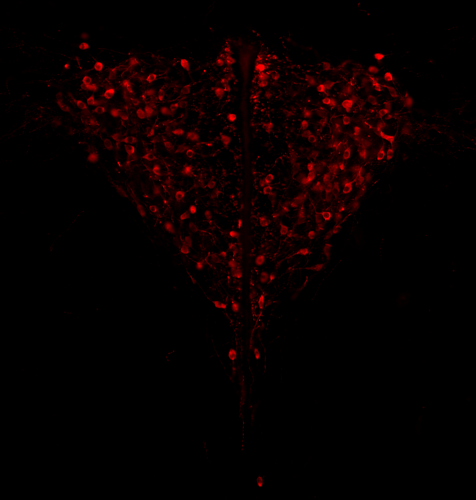

31 Oct 2022

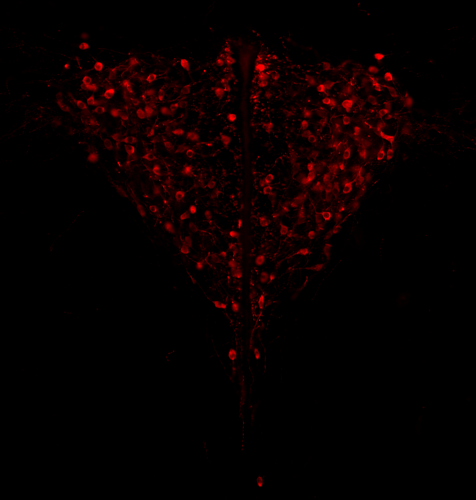

Genotypic sex shapes maternal care in the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoidesLouise D Heitzmann, Marie Challe, Julie Perez, Laia Castell, Evelyne Galibert, Agnes Martin, Emmanuel Valjent, Frederic Veyrunes https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.05.487174Effect of sex chromosomes on mammalian behaviour: a case study in pygmy miceRecommended by Gabriel Marais and Trine Bilde based on reviews by Marion Anne-Lise Picard, Caroline Hu and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Marion Anne-Lise Picard, Caroline Hu and 1 anonymous reviewer

In mammals, it is well documented that sexual dimorphism and in particular sex differences in behaviour are fine-tuned by gonadal hormonal profiles. For example, in lemurs, where female social dominance is common, the level of testosterone in females is unusually high compared to that of other primate females (Petty and Drea 2015). Recent studies however suggest that gonadal hormones might not be the only biological factor involved in establishing sexual dimorphism, sex chromosomes might also play a role. The four core genotype (FCG) model and other similar systems allowing to decouple phenotypic and genotypic sex in mice have provided very convincing evidence of such a role (Gatewood et al. 2006; Arnold and Chen 2009; Arnold 2020a, 2020b). This however is a new field of research and the role of sex chromosomes in establishing sexually dimorphic behaviours has not been studied very much yet. Moreover, the FCG model has some limits. Sry, the male determinant gene on the mammalian Y chromosome might be involved in some sex differences in neuroanatomy, but Sry is always associated with maleness in the FCG model, and this potential role of Sry cannot be studied using this system. Heitzmann et al. have used a natural system to approach these questions. They worked on the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoides, in which a modified X chromosome called X* can feminize X*Y individuals, which offers a great opportunity for elegant experiments on the effects of sex chromosomes versus hormones on behaviour. They focused on maternal care and compared pup retrieval, nest quality, and mother-pup interactions in XX, X*X and X*Y females. They found that X*Y females are significantly better at retrieving pups than other females. They are also much more aggressive towards the fathers than other females, preventing paternal care. They build nests of poorer quality but have similar interactions with pups compared to other females. Importantly, no significant differences were found between XX and X*X females for these traits, which points to an effect of the Y chromosome in explaining the differences between X*Y and other females (XX, X*X). Also, another work from the same group showed similar gonadal hormone levels in all the females (Veyrunes et al. 2022). Heitzmann et al. made a number of predictions based on what is known about the neuroanatomy of rodents which might explain such behaviours. Using cytology, they looked for differences in neuron numbers in the hypothalamus involved in the oxytocin, vasopressin and dopaminergic pathways in XX, X*X and X*Y females, but could not find any significant effects. However, this part of their work relied on very small sample sizes and they used virgin females instead of mothers for ethical reasons, which greatly limited the analysis. Interestingly, X*Y females have a higher reproductive performance than XX and X*X ones, which compensate for the cost of producing unviable YY embryos and certainly contribute to maintaining a high frequency of X* in many African pygmy mice populations (Saunders et al. 2014, 2022). X*Y females are probably solitary mothers contrary to other females, and Heitzmann et al. have uncovered a divergent female strategy in this species. Their work points out the role of sex chromosomes in establishing sex differences in behaviours. References Arnold AP (2020a) Sexual differentiation of brain and other tissues: Five questions for the next 50 years. Hormones and Behavior, 120, 104691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2020.104691 Arnold AP (2020b) Four Core Genotypes and XY* mouse models: Update on impact on SABV research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 119, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.09.021 Arnold AP, Chen X (2009) What does the “four core genotypes” mouse model tell us about sex differences in the brain and other tissues? Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 30, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.11.001 Gatewood JD, Wills A, Shetty S, Xu J, Arnold AP, Burgoyne PS, Rissman EF (2006) Sex Chromosome Complement and Gonadal Sex Influence Aggressive and Parental Behaviors in Mice. Journal of Neuroscience, 26, 2335–2342. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3743-05.2006 Heitzmann LD, Challe M, Perez J, Castell L, Galibert E, Martin A, Valjent E, Veyrunes F (2022) Genotypic sex shapes maternal care in the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoides. bioRxiv, 2022.04.05.487174, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.05.487174 Petty JMA, Drea CM (2015) Female rule in lemurs is ancestral and hormonally mediated. Scientific Reports, 5, 9631. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09631 Saunders PA, Perez J, Rahmoun M, Ronce O, Crochet P-A, Veyrunes F (2014) Xy Females Do Better Than the Xx in the African Pygmy Mouse, Mus Minutoides. Evolution, 68, 2119–2127. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12387 Saunders PA, Perez J, Ronce O, Veyrunes F (2022) Multiple sex chromosome drivers in a mammal with three sex chromosomes. Current Biology, 32, 2001-2010.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.03.029 Veyrunes F, Perez J, Heitzmann L, Saunders PA, Givalois L (2022) Separating the effects of sex hormones and sex chromosomes on behavior in the African pygmy mouse Mus minutoides, a species with XY female sex reversal. bioRxiv, 2022.07.11.499546. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.11.499546 | Genotypic sex shapes maternal care in the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoides | Louise D Heitzmann, Marie Challe, Julie Perez, Laia Castell, Evelyne Galibert, Agnes Martin, Emmanuel Valjent, Frederic Veyrunes | <p>Sexually dimorphic behaviours, such as parental care, have long been thought to be driven mostly, if not exclusively, by gonadal hormones. In the past two decades, a few studies have challenged this view, highlighting the direct influence of th... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Reproduction and Sex | Gabriel Marais | 2022-04-08 20:09:58 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer