FRAÏSSE Christelle

- UMR8198 (Evo-Eco-Paleo), CNRS, Lille, France

- Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Hybridization / Introgression, Molecular Evolution, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Speciation

- recommender

Recommendations: 2

Reviews: 3

Recommendations: 2

Domestication of different varieties in the cheese-making fungus Geotrichum candidum

Diverse outcomes in cheese fungi domestication

Recommended by Christelle Fraïsse based on reviews by Delphine Sicard and 1 anonymous reviewerDomestication is a complex process that imprints the demography and the genomes of domesticated populations, enforcing strong selective pressures on traits favourable to humans, e.g. for food production [1]. Domestication has been quite intensely studied in plants and animals, but less so in micro-organisms such as fungi, despite their assets (e.g. their small genomes and tractability in the lab). This elegant study by Bennetot and collaborators [2] on the cheese-making fungus Geotrichum candidum adds to the mounting body of studies in the genomics of fungi, proving they are excellent models in evolutionary biology for studying adaptation and drift in eukaryotes [3].

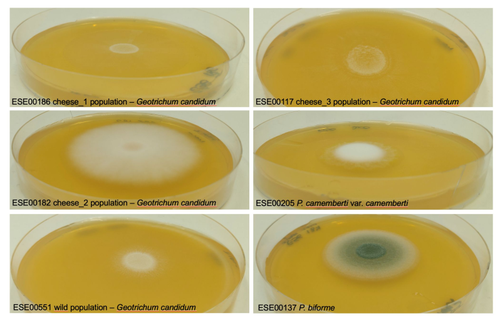

Bennetot et al. newly showed with whole genome sequences that all G. candidum strains isolated from cheese form a monophyletic clade subdivided into three genetically differentiated populations with several admixed strains, while the wild strains sampled from diverse geographic locations form a sister clade. This suggests the wild progenitor was not sampled in the present study and calls for future exciting work on the domestication history of the G. candidum fungus. The authors scanned the genomes for footprints of adaptation to the cheese environment and identified promising candidates, such as a gene involved in iron uptake (this element is limiting in cheese). Their functional genome analysis also provides evidence for higher contents of transposable elements in cheese-making strains, likely due to relaxed selection during the domestication process.

This paper is particularly impressive in that the authors complemented the population genomic approach with the phenotypic characterization of the strains and tested their ability to outcompete common fungal food spoilers. The authors convincingly showed that cheese-making strains display phenotypic differences relative to wild relatives for multiple traits such as slower growth, lower proteolysis activity and a greater amount of volatiles attractive to consumers, these phenotypes being beneficial for cheese making.

Finally, this work is particularly inspiring because it thoroughly discusses convergent evolution during domestication in different cheese-associated fungi. Indeed, studying populations experiencing similar environmental pressures is fundamental to understanding whether evolution is repeatable [4]. For instance, all three cheese populations of G. candidum exhibit a lower genetic diversity than wild populations. However, only one population displays a stronger domestication syndrome, resembling the Penicillium camemberti situation [5]. Furthermore, different cheese-making practices may have led to varying situations with clonal lineages in non-Roquefort P. roqueforti and P. camemberti [5, 6], while the cheese-making G. candidum populations still harbour some diversity. In a nutshell, Bennetot's study makes an important contribution to evolutionary biology and highlights the value of diversifying our model organisms toward under-represented clades.

REFERENCES

[1] Diamond J (2002) Evolution, consequences and future of plant and animal domestication. Nature 418: 700–707. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01019

[2] Bennetot B, Vernadet J-P, Perkins V, Hautefeuille S, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, O’Donnell S, Snirc A, Grondin C, Lessard M-H, Peron A-C, Labrie S, Landaud S, Giraud T, Ropars J (2023) Domestication of different varieties in the cheese-making fungus Geotrichum candidum. bioRxiv, 2022.05.17.492043, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.17.492043

[3] Gladieux P, Ropars J, Badouin H, Branca A, Aguileta G, de Vienne DM, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Branco S, Giraud T (2014) Fungal evolutionary genomics provides insight into the mechanisms of adaptive divergence in eukaryotes. Mol. Ecol. 23: 753–773. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12631

[4] Bolnick DI, Barrett RD, Oke KB, Rennison DJ, Stuart YE (2018) (Non)Parallel evolution. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 49: 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110617-062240

[5] Ropars J, Didiot E, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Bennetot B, Coton M, Poirier E, Coton E, Snirc A, Le Prieur S, Giraud T (2020) Domestication of the Emblematic White Cheese-Making Fungus Penicillium camemberti and Its Diversification into Two Varieties. Current Biol. 30: 4441–4453.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.082

[6] Dumas, E, Feurtey, A, Rodríguez de la Vega, RC, Le Prieur S, Snirc A, Coton M, Thierry A, Coton E, Le Piver M, Roueyre D, Ropars J, Branca A, Giraud T (2020) Independent domestication events in the blue-cheese fungus Penicillium roqueforti. Mol Ecol. 29: 2639–2660. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15359

Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in mice

Tinder in mice: A match made with the sense of smell

Recommended by Christelle Fraïsse based on reviews by Angeles de Cara, Ludovic Claude Maisonneuve ? and 1 anonymous reviewerDifferentiation-based genome scans lie at the core of speciation and adaptation genomics research. Dating back to Lewontin & Krakauer (1973), they have become very popular with the advent of genomics to identify genome regions of enhanced differentiation relative to neutral expectations. These regions may represent genetic barriers between divergent lineages and are key for studying reproductive isolation. However, genome scan methods can generate a high rate of false positives, primarily if the neutral population structure is not accounted for (Bierne et al. 2013). Moreover, interpreting genome scans can be challenging in the context of secondary contacts between diverging lineages (Bierne et al. 2011), because the coupling between different components of reproductive isolation (local adaptation, intrinsic incompatibilities, mating preferences, etc.) can occur readily, thus preventing the causes of differentiation from being determined.

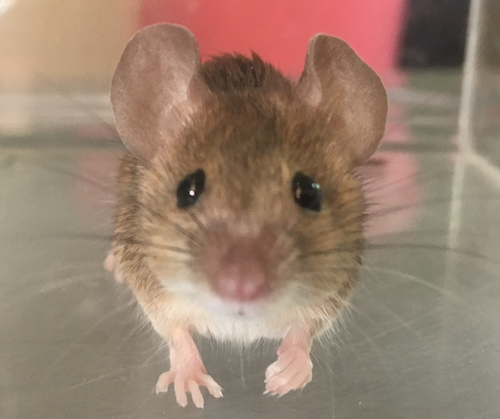

Smadja and collaborators (2022) applied a sophisticated genome scan for trait association (BAYPASS, Gautier 2015) to underlie the genetic basis of a polygenetic behaviour: assortative mating in hybridizing mice. My interest in this neat study mainly relies on two reasons. First, the authors used an ingenious geographical setting (replicate pairs of “Choosy” versus “Non-Choosy” populations) with multi-way comparisons to narrow down the list of candidate regions resulting from BAYPASS. The latter corrects for population structure, handles cost-effective pool-seq data and allows for gene-based analyses that aggregate SNP signals within a gene. These features reinforce the set of outlier genes detected; however, not all are expected to be associated with mating preference.

The second reason why this study is valuable to me is that Smadja et al. (2022) complemented the population genomic approach with functional predictions to validate the genetic signal. In line with previous behavioural and chemical assays on the proximal mechanisms of mating preferences, they identified multiple olfactory and vomeronasal receptor genes as highly significant candidates. Therefore, combining genomic signals with functional analyses is a clever way to provide insights into the causes of reproductive isolation, especially when multiple barriers are involved. This is typically true for reinforcement (Butlin & Smadja 2018), suspected to occur in these mice because, in that case, assortative mating (a prezygotic barrier) evolves in response to the cost of hybridization (for example, due to hybrid inviability).

As advocated by the authors, their study paves the way for future work addressing the genetic basis of reinforcement, a trait of major evolutionary importance for which we lack empirical data. They also make a compelling case using complementary approaches that olfactory and vomeronasal receptors have a central role in mammal speciation.

References:

Bierne N, Welch J, Loire E, Bonhomme F, David P (2011) The coupling hypothesis: why genome scans may fail to map local adaptation genes. Mol Ecol 20: 2044–2072. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05080.x

Bierne N, Roze D, Welch JJ (2013) Pervasive selection or is it…? why are FST outliers sometimes so frequent? Mol Ecol 22: 2061–2064. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12241

Butlin RK, Smadja CM (2018) Coupling, Reinforcement, and Speciation. Am Nat 191:155–172. https://doi.org/10.1086/695136

Gautier M (2015) Genome-Wide Scan for Adaptive Divergence and Association with Population-Specific Covariates. Genetics 201:1555–1579. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.115.181453

Lewontin RC, Krakauer J (1973) Distribution of gene frequency as a test of the theory of selective neutrality of polymorphisms. Genetics 74: 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/74.1.175

Smadja CM, Loire E, Caminade P, Severac D, Gautier M, Ganem G (2022) Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in mice. bioRxiv, 2022.07.21.500634, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.21.500634

Reviews: 3

Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow in a butterfly

Is genetic diversity enhanced by a supergene?

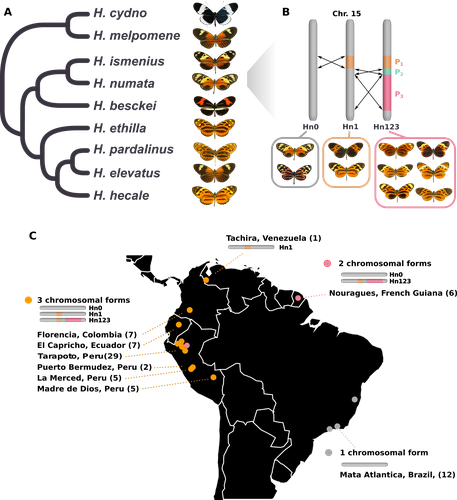

Recommended by Chris Jiggins based on reviews by Christelle Fraïsse and 2 anonymous reviewersThe butterfly species Heliconius numata has a remarkable wing pattern polymorphism, with multiple pattern morphs all controlled by a single genetic locus, which harbours multiple inversions. Each morph is a near-perfect mimic of a species in the fairly distantly related genus of butterflies, Melinaea.

The article by Rodríguez de Cara et al (2023) argues that the balanced polymorphism at this single wing patterning locus actually has a major effect on genetic diversity across the whole genome. First, polymorphic populations within H. numata are more dioverse than those without polymorphism. Second, H. numata is more genetically diverse than other related species and finally reconstruction of historical demography suggests that there has been a recent increase in effective population size, putatively associated with the acquisition of the supergene polymorphism. The supergene itself generates disassortative mating, such that morphs prefer to mate with others dissimilar to themselves - in this way it is similar to mechanisms for preventing inbreeding such as self-incompatibility loci in plants. This provides a potential mechanism whereby non-random mating patterns could increase effective population size. The authors also explore this mechanism using forward simulations, and show that mating patterns at a single locus can influence linked genetic diversity over a large scale.

Overall, this is an intriguing study, which suggests a far more widespread genetic impact of a single locus than might be expected. There are interesting parallels with mechanisms of inbreeding prevention in plants, such as the Pin/Thrum polymorphism in Primula, which also rely on mating patterns determined by a single locus but presumably also influence genetic diversity genome-wide by promoting outbreeding.

REFERENCES

Rodríguez de Cara MÁ, Jay P, Rougemont Q, Chouteau M, Whibley A, Huber B, Piron-Prunier F, Ramos RR, Freitas AVL, Salazar C, Silva-Brandão KL, Torres TT, Joron M (2023) Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow. bioRxiv, 2021.09.29.462348, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.29.462348

A genomic assessment of the marine-speciation paradox within the toothed whale superfamily Delphinoidea

Reticulated evolution marks the rapid diversification of the Delphinoidae

Recommended by Michael C. Fontaine based on reviews by Christelle Fraïsse, Simon Henry Martin, Andrew Foote and 2 anonymous reviewersHistorically neglected or considered a rare aberration in animals under the biological species concept, interspecific hybridisation has by now been recognised to be taxonomically widespread, particularly in rapidly diversifying groups (Dagilis et al. 2021; Edelman & Mallet 2021; Mallet et al. 2016; Seehausen 2004). Yet the prevalence of introgressive hybridizations, its evolutionary significance, and its impact on species diversification remain a hot topic of research in evolutionary biology. The rapid increase in genomic resources now available for non-model species has significantly contributed to the detection of introgressive hybridization across taxa showing that reticulated evolution is far more common in the animal kingdom than historically considered. Yet, detecting it, quantifying its magnitude, and assessing its evolutionary significance remains a challenging endeavour with constantly evolving methodologies to better explore and exploit genomic data (Blair & Ané 2020; Degnan & Rosenberg 2009; Edelman & Mallet 2021; Hibbins & Hahn 2022).

In the marine realm, the dearth of geographic barriers and the large dispersal abilities of pelagic species like cetaceans have raised the questions of how populations and species can diverge and adapt to distinct ecological conditions in face of potentially large gene-flow, the so-called marine speciation paradox (Bierne et al. 2003). Contemporaneous hybridization among cetacean species has been widely documented in nature despite large phenotypic differences (Crossman et al. 2016). The historical prevalence of reticulated evolution, its evolutionary significance, and how it might have impacted the evolutionary history and diversification of the cetaceans have however remained elusive so far. Recent phylogenomic studies suggested that introgression has been prevalent in cetacean evolutionary history with instances reported among baleen whales (mysticetes) (Árnason et al. 2018) and among toothed whales (odontocetes), especially in the rapidly diversifying dolphins family of the Delphininae (Guo et al. 2021; Moura et al. 2020).

Analysing publicly available whole-genome data from nine cetacean species across three families of Delphinoidae – dolphins, porpoises, and monondontidae – using phylogenomics and demo-genetics approaches, Westbury and colleagues (2022) take a step further in documenting that evolution among these species has been far from a simple bifurcating tree. Instead, their study describes widespread occurrences of introgression among Delphinoidae, drawing a complex picture of reticulated evolutionary history. After describing major topology discordance in phylogenetic gene trees along the genome, the authors use a panel of approaches to disentangle introgression from incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), the two most common causes of tree topology discordances (Hibbins & Hahn 2022). Applying popular tests that separate introgression from ILS, such as the Patterson’s D (a.k.a. ABBA-BABA) test (Durand et al. 2011; Green et al. 2010), QuIBL (Edelman et al. 2019), and D-FOIL (Pease & Hahn 2015), the authors report that signals of introgression are present in the genomes of most (if not all) the cetacean species included in their study. However, this picture needs to be nuanced. Most introgression signals seem to echo old introgression events that occurred primarily among ancestors. This is suggested by the differential signals of topology discordance along the genome when considering sliding windows along the genome of varying sizes (50kb, 100kb, and 1Mb), and by patterns of excess derived allele sharing along branches of the species tree, as captured by the f-branch test (Malinsky et al. 2021; Malinsky et al. 2018). The authors further investigated the dynamic of cessation of gene flow (and/or ILS) between species using the F1 hybrid PSMC (or hPSMC) approach (Cahill et al. 2016). By estimating the cross-coalescent rates (CRR) between species pairs with time in light of previously estimated species divergence times (McGowen et al. 2020), the authors report that gene flow (and/or ILS) most likely has stopped by now among most species, but it may have lasted for more than half of the time since the species split from each other. According to the author, this result may reflect the slow process by which reproductive isolation would have evolved between cetacean lineages, and that species isolation was marked by significant introgression events.

Now, while the present study provides a good overview of how complex is the reticulated evolutionary history of the Delphinoidae, getting a complete picture will require overcoming a few important limitations. The first ones are methodological and related to the phylogenomic analyses. Given the sampling design with one diploid genome per species, the authors could not phase the data into the parental haplotypes, but instead relied on a majority consensus creating mosaic haploidized genomes representing a mixture between the two parental copies. Moreover, by using large genomic windows (≥50kb) that likely span multiple independent loci, phylogenetic analyses in windows encompassed distinct phylogenetic signals, potentially leading to bias and inaccuracy in the inferences. Thawornwattana et al (2018) previously showed that this “concatenation approach” could significantly impact phylogenetic inferences. They proposed instead to use loci small enough to minimise the risk of intra-locus recombination and to consider them in blocks of non-recombining loci along the genome in order to conduct phylogenetic analysed, ideally under the multi-species coalescent (MSC) that can account for ILS (e.g. BPP; Flouri et al. 2018; Jiao et al. 2020; Yang 2015). Such an approach applied to the diversification of the Delphinidae may reveal substantial changes compared to the currently admitted species tree.

Inaccuracy in the species tree estimation may have a major impact on the introgression analyses conducted in this study since the species tree and branching order must be supplied in the introgression analyses to properly disentangle introgression from ILS. Here, the authors rely on the tree topology that was previously estimated in McGowen et al. (2020), which they also recovered using their consensus estimation from ASTRAL-III (Zhang et al. 2018). While the methodologies accounted to a certain extent for ILS, albeit with potential bias induced by the concatenation approach, they ignore the presumably large amount of introgression among species during the diversification process. Estimating species branching order while ignoring introgression can lead to major bias in the phylogenetic inference and can lead to incorrect topologies. Even if these MSC-based methods account for ILS, inferences can become very inaccurate or even break down as gene flow increases (see for ex. Jiao et al. 2020; Müller et al. in press; Solís-Lemus et al. 2016). Dedicated approaches have been developed to model explicitly introgression together with ILS to estimate phylogenetic networks (Blair & Ané 2020; Rabier et al. 2021) or in isolation-with-migration model (Müller et al. in press; Wang et al. 2020). Future studies revisiting the reticulated evolutionary history of the Delphinoidae with such approaches may not only precise the species branching order, but also deliver a finer view of the magnitude and prevalence of introgression during the evolutionary history of these species.

A final part of Westbury et al. (2022)'s study set out to test whether historical periods of low abundance could have facilitated hybridization among Delphinoidae species. During these periods of low abundance, species may encounter only a limited number of conspecifics and may consider individuals from other species as suitable mating partners, leading to hybridisation (Crossman et al. 2016; Edwards et al. 2011; Westbury et al. 2019). The authors tested this hypothesis by considering genome-wide genetic diversity (or heterozygosity) as a proxy of historical effective population size (Ne), itself as a proxy of the evolution of census size with time. They also try to link historical Ne variation (from PSMC, Li & Durbin 2011) with their estimated time to cessation of gene flow or ILS (from the CRR of hPSMC). However, no straightforward relationship was found between the genetic diversity and the propensity of species to hybridize, nor was there any clear link between Ne variation through time and the cessation of gene flow or ILS. Such a lack of relationship may not come as a surprise, since the determinants of genome-wide genetic diversity and its variation through evolutionary time-scale are far more diverse and complex than just a direct link with hybridization, introgression, or even with the census population size. In fact, genetic diversity results from the balance between all the evolutionary processes at play in the species' evolutionary history (see the review of Ellegren & Galtier 2016). Other important factors can strongly impact genetic diversity, including demography and structure, but also linked selection (Boitard et al. 2022; Buffalo 2021; Ellegren & Galtier 2016).

All in all, Westbury and coll. (2022) present here an interesting study providing an additional step towards resolving and understanding the complex evolutionary history of the Delphinoidae, and shedding light on the importance of introgression during the diversification of these cetacean species. Prospective work improving upon the taxonomic sampling, with additional genomic data for each species, considered with dedicated approaches tailored at estimating species tree or network while accounting for ILS and introgression will be key for refining the picture depicted in this study. Down the road, altogether these studies will contribute to assessing the evolutionary significance of introgression on the diversification of Delphinoides, and more generally on the diversification of cetacean species, which still remain an open and exciting perspective.

References

Árnason Ú, Lammers F, Kumar V, Nilsson MA, Janke A (2018) Whole-genome sequencing of the blue whale and other rorquals finds signatures for introgressive gene flow. Science Advances 4, eaap9873. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aap9873

Bierne N, Bonhomme F, David P (2003) Habitat preference and the marine-speciation paradox. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 270, 1399-1406. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2003.2404

Blair C, Ané C (2020) Phylogenetic Trees and Networks Can Serve as Powerful and Complementary Approaches for Analysis of Genomic Data. Systematic Biology 69, 593-601. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syz056

Boitard S, Arredondo A, Chikhi L, Mazet O (2022) Heterogeneity in effective size across the genome: effects on the inverse instantaneous coalescence rate (IICR) and implications for demographic inference under linked selection. Genetics 220, iyac008. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyac008

Buffalo V (2021) Quantifying the relationship between genetic diversity and population size suggests natural selection cannot explain Lewontin's Paradox. e-Life 10, e67509. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.67509

Cahill JA, Soares AE, Green RE, Shapiro B (2016) Inferring species divergence times using pairwise sequential Markovian coalescent modelling and low-coverage genomic data. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 371, 20150138. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0138

Crossman CA, Taylor EB, Barrett‐Lennard LG (2016) Hybridization in the Cetacea: widespread occurrence and associated morphological, behavioral, and ecological factors. Ecology and Evolution 6, 1293-1303. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.1913

Dagilis AJ, Peede D, Coughlan JM, Jofre GI, D’Agostino ERR, Mavengere H, Tate AD, Matute DR (2021) 15 years of introgression studies: quantifying gene flow across Eukaryotes. biorXiv, 2021.1106.1115.448399. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.15.448399

Degnan JH, Rosenberg NA (2009) Gene tree discordance, phylogenetic inference and the multispecies coalescent. Trends Ecol Evol 24, 332-340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.01.009

Durand EY, Patterson N, Reich D, Slatkin M (2011) Testing for ancient admixture between closely related populations. Mol Biol Evol 28, 2239-2252. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msr048

Edelman NB, Frandsen PB, Miyagi M, Clavijo B, Davey J, Dikow RB, Garcia-Accinelli G, Van Belleghem SM, Patterson N, Neafsey DE, Challis R, Kumar S, Moreira GRP, Salazar C, Chouteau M, Counterman BA, Papa R, Blaxter M, Reed RD, Dasmahapatra KK, Kronforst M, Joron M, Jiggins CD, McMillan WO, Di Palma F, Blumberg AJ, Wakeley J, Jaffe D, Mallet J (2019) Genomic architecture and introgression shape a butterfly radiation. Science 366, 594-599. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw2090

Edelman NB, Mallet J (2021) Prevalence and Adaptive Impact of Introgression. Annual Review of Genetics 55, 265-283. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genet-021821-020805

Edwards CJ, Suchard MA, Lemey P, Welch JJ, Barnes I, Fulton TL, Barnett R, O'Connell TC, Coxon P, Monaghan N, Valdiosera CE, Lorenzen ED, Willerslev E, Baryshnikov GF, Rambaut A, Thomas MG, Bradley DG, Shapiro B (2011) Ancient hybridization and an Irish origin for the modern polar bear matriline. Curr Biol 21, 1251-1258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.058

Ellegren H, Galtier N (2016) Determinants of genetic diversity. Nat Rev Genet 17, 422-433. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.58

Flouri T, Jiao X, Rannala B, Yang Z (2018) Species Tree Inference with BPP Using Genomic Sequences and the Multispecies Coalescent. Mol Biol Evol 35, 2585-2593. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy147

Green RE, Krause J, Briggs AW, Maricic T, Stenzel U, Kircher M, Patterson N, Li H, Zhai W, Fritz MH, Hansen NF, Durand EY, Malaspinas AS, Jensen JD, Marques-Bonet T, Alkan C, Prufer K, Meyer M, Burbano HA, Good JM, Schultz R, Aximu-Petri A, Butthof A, Hober B, Hoffner B, Siegemund M, Weihmann A, Nusbaum C, Lander ES, Russ C, Novod N, Affourtit J, Egholm M, Verna C, Rudan P, Brajkovic D, Kucan Z, Gusic I, Doronichev VB, Golovanova LV, Lalueza-Fox C, de la Rasilla M, Fortea J, Rosas A, Schmitz RW, Johnson PLF, Eichler EE, Falush D, Birney E, Mullikin JC, Slatkin M, Nielsen R, Kelso J, Lachmann M, Reich D, Paabo S (2010) A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science 328, 710-722. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188021

Guo W, Sun D, Cao Y, Xiao L, Huang X, Ren W, Xu S, Yang G (2021) Extensive Interspecific Gene Flow Shaped Complex Evolutionary History and Underestimated Species Diversity in Rapidly Radiated Dolphins. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 29, 353-367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10914-021-09581-6

Hibbins MS, Hahn MW (2022) Phylogenomic approaches to detecting and characterizing introgression. Genetics 220, iyab173. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyab173

Jiao X, Flouri T, Rannala B, Yang Z (2020) The Impact of Cross-Species Gene Flow on Species Tree Estimation. Syst Biol 69, 830-847. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syaa001

Li H, Durbin R (2011) Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature 475, 493-496. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10231

Malinsky M, Matschiner M, Svardal H (2021) Dsuite - Fast D-statistics and related admixture evidence from VCF files. Mol Ecol Resour 21, 584-595. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13265

Malinsky M, Svardal H, Tyers AM, Miska EA, Genner MJ, Turner GF, Durbin R (2018) Whole-genome sequences of Malawi cichlids reveal multiple radiations interconnected by gene flow. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2, 1940-1955. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0717-x

Mallet J, Besansky N, Hahn MW (2016) How reticulated are species? Bioessays 38, 140-149. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201500149

McGowen MR, Tsagkogeorga G, Alvarez-Carretero S, Dos Reis M, Struebig M, Deaville R, Jepson PD, Jarman S, Polanowski A, Morin PA, Rossiter SJ (2020) Phylogenomic Resolution of the Cetacean Tree of Life Using Target Sequence Capture. Syst Biol 69, 479-501. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syz068

Moura AE, Shreves K, Pilot M, Andrews KR, Moore DM, Kishida T, Möller L, Natoli A, Gaspari S, McGowen M, Chen I, Gray H, Gore M, Culloch RM, Kiani MS, Willson MS, Bulushi A, Collins T, Baldwin R, Willson A, Minton G, Ponnampalam L, Hoelzel AR (2020) Phylogenomics of the genus Tursiops and closely related Delphininae reveals extensive reticulation among lineages and provides inference about eco-evolutionary drivers. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 146,107047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2020.106756

Müller NF, Ogilvie HA, Zhang C, Fontaine MC, Amaya-Romero JE, Drummond AJ, Stadler T (in press) Joint inference of species histories and gene flow. Syst Biol.

Pease JB, Hahn MW (2015) Detection and Polarization of Introgression in a Five-Taxon Phylogeny. Syst Biol 64, 651-662. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syv023

Rabier CE, Berry V, Stoltz M, Santos JD, Wang W, Glaszmann JC, Pardi F, Scornavacca C (2021) On the inference of complex phylogenetic networks by Markov Chain Monte-Carlo. PLoS Comput Biol 17, e1008380. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008380

Seehausen O (2004) Hybridization and adaptive radiation. Trends Ecol Evol 19, 198-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.01.003

Solís-Lemus C, Yang M, Ané C (2016) Inconsistency of Species Tree Methods under Gene Flow. Syst Biol 65, 843-851. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syw030

Thawornwattana Y, Dalquen D, Yang Z, Tamura K (2018) Coalescent Analysis of Phylogenomic Data Confidently Resolves the Species Relationships in the Anopheles gambiae Species Complex. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35, 2512-2527. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy158

Wang K, Mathieson I, O’Connell J, Schiffels S (2020) Tracking human population structure through time from whole genome sequences. PLOS Genetics 16, e1008552. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008552

Westbury MV, Cabrera AA, Rey-Iglesia A, Cahsan BD, Duchêne DA, Hartmann S, Lorenzen ED (2022) A genomic assessment of the marine-speciation paradox within the toothed whale superfamily Delphinoidea. bioRxiv, 2020.10.23.352286, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.23.352286

Westbury MV, Petersen B, Lorenzen ED (2019) Genomic analyses reveal an absence of contemporary introgressive admixture between fin whales and blue whales, despite known hybrids. PLoS ONE 14, e0222004. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222004

Yang Z (2015) The BPP program for species tree estimation and species delimitation. Current Zoology 61, 854-865. https://doi.org/10.1093/czoolo/61.5.854

Zhang C, Rabiee M, Sayyari E, Mirarab S (2018) ASTRAL-III: polynomial time species tree reconstruction from partially resolved gene trees. BMC Bioinformatics 19, 153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-018-2129-y

Systematics and geographical distribution of Galba species, a group of cryptic and worldwide freshwater snails

The challenge of delineating species when they are hidden

Recommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by Pavel Matos, Christelle Fraïsse and Niklas WahlbergThe science of naming species (taxonomy) has been renewed with the developments of molecular sequencing, digitization of museum specimens, and novel analytical tools. However, naming species can be highly subjective, sometimes considered as an art [1], because it is based on human-based criteria that vary among taxonomists. Nonetheless, taxonomists often argue that species names are hypotheses, which are therefore testable and refutable as new evidence is provided. This challenge comes with a more and more recognized and critical need for rigorously delineated species not only for producing accurate species inventories, but more importantly many questions in evolutionary biology (e.g. speciation), ecology (e.g. ecosystem structure and functioning), conservation biology (e.g. targeting priorities) or biogeography (e.g. diversification processes) depend in part on those species inventories and our knowledge of species [2-3]. Inaccurate species boundaries or diversity estimates may lead us to deliver biased answers to those questions, exactly as phylogenetic trees must be reconstructed rigorously and analyzed critically because they are a first step toward discussing broader questions [2-3]. In this context, biological diversity needs to be studied from multiple and complementary perspectives requiring the collaboration of morphologists, molecular biologists, biogeographers, and modelers [4-5]. Integrative taxonomy has been proposed as a solution to tackle the challenge of delimiting species [2], especially in highly diverse and undocumented groups of organisms.

In an elegant study that harbors all the characteristics of an integrative approach, Alda et al. [6] tackle the delimitation of species within the snail genus Galba (Lymnaeidae). Snails of this genus represent a peculiar case study for species delineation with a long and convoluted taxonomic history in which previous works recognized a number of species ranging from 4 to 30. The confusion is likely due to a loose morphology (labile shell features and high plasticity), which makes the identification and naming of species very unstable and likely subjective. An integrative taxonomic approach was needed. After two decades of taxon sampling and visits of type localities, the authors present an impressively dense taxon sampling at a global scale for the genus, which includes all described species. When it comes to delineate species, taxon sampling is often the key if we want to embrace the genetic and morphological diversity. Molecular data was obtained for several types of markers (microsatellites and DNA sequences for four genes), which were combined to morphology of shell and of internal organs, and to geographic distribution. All the data are thoroughly analyzed with cutting-edge methods starting from Bayesian phylogenetic reconstructions using multispecies coalescent models, followed by models of species delimitation based on the molecular specimen-level phylogeny, and then Bayesian divergence time estimates. They also used probabilistic models of ancestral state estimation to infer the ancestral phenotypic state of the Galba ancestors.

Their numerous phylogenetic and delimitation analyses allow to redefine the species boundaries that indicate that the genus Galba comprises six species. Interestingly, four of these species are morphologically cryptic and likely constitute species with extensive genetic diversity and widespread geographic distribution. The other two species have more geographically restricted distributions and exhibit an alternative morphology that is more phylogenetically derived than the cryptic one. Although further genomic studies would be required to strengthen some species status, this novel delimitation of Galba species has important implications for our understanding of convergence and morphological stasis, or the role for stabilizing selection in amphibious habitats; topics that are rarely addressed with invertebrate groups. For instance, in terms of macroevolutionary history, it is striking that an invertebrate clade of that age (22 million years ago) has only given birth to six species today. Including 30 (ancient taxonomy) or 6 (integrative taxonomy) species in a similar amount of evolutionary time does not tell us the same story when studying the diversification processes [7]. Here, Alda et al. [6] present a convincing case study that should foster similar studies following their approach, which will provide stimulating perspectives for testing the concepts of species and their effects on evolutionary biology.

References

[1] Ohl, M. (2018). The art of naming. MIT Press.

[2] Dayrat, B. (2005). Towards integrative taxonomy. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 85(3), 407–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00503.x

[3] De Queiroz, K. (2007). Species concepts and species delimitation. Systematic Biology, 56(6), 879–886. doi: 10.1080/10635150701701083

[4] Padial, J. M., Miralles, A., De la Riva, I., and Vences, M. (2010). The integrative future of taxonomy. Frontiers in Zoology, 7(1), 16. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-7-16

[5] Schlick-Steiner, B. C., Steiner, F. M., Seifert, B., Stauffer, C., Christian, E., and Crozier, R. H. (2010). Integrative taxonomy: A multisource approach to exploring biodiversity. Annual Review of Entomology, 55(1), 421–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085432

[6] Alda, P. et al. (2019). Systematics and geographical distribution of Galba species, a group of cryptic and worldwide freshwater snails. BioRxiv, 647867, v3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/647867

[7] Ruane, S., Bryson, R. W., Pyron, R. A., and Burbrink, F. T. (2014). Coalescent species delimitation in milksnakes (Genus Lampropeltis) and impacts on phylogenetic comparative analyses. Systematic Biology, 63(2), 231–250. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syt099