Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▲ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

17 May 2021

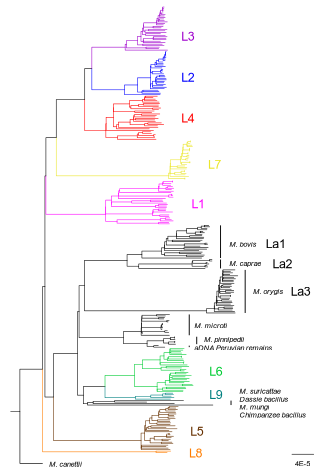

Relative time constraints improve molecular datingGergely J Szollosi, Sebastian Hoehna, Tom A Williams, Dominik Schrempf, Vincent Daubin, Bastien Boussau https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.17.343889Dating with constraintsRecommended by Cécile Ané based on reviews by David Duchêne and 1 anonymous reviewerEstimating the absolute age of diversification events is challenging, because molecular sequences provide timing information in units of substitutions, not years. Additionally, the rate of molecular evolution (in substitutions per year) can vary widely across lineages. Accurate dating of speciation events traditionally relies on non-molecular data. For very fast-evolving organisms such as SARS-CoV-2, for which samples are obtained over a time span, the collection times provide this external information from which we can learn the rate of molecular evolution and date past events (Boni et al. 2020). In groups for which the fossil record is abundant, state-of-the-art dating methods use fossil information to complement molecular data, either in the form of a prior distribution on node ages (Nguyen & Ho 2020), or as data modelled with a fossilization process (Heath et al. 2014). Dating is a challenge in groups that lack fossils or other geological evidence, such as very old lineages and microbial lineages. In these groups, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) events have been identified as informative about relative dates: the ancestor of the gene's donor must be older than the descendants of the gene's recipient. Previous work using HGTs to date phylogenies have used methodologies that are ad-hoc (Davín et al 2018) or employ a small number of HGTs only (Magnabosco et al. 2018, Wolfe & Fournier 2018). Szöllősi et al. (2021) present and validate a Bayesian approach to estimate the age of diversification events based on relative information on these ages, such as implied by HGTs. This approach is flexible because it is modular: constraints on relative node ages can be combined with absolute age information from fossil data, and with any substitution model of molecular evolution, including complex state-of-art models. To ease the computational burden, the authors also introduce a two-step approach, in which the complexity of estimating branch lengths in substitutions per site is decoupled from the complexity of timing the tree with branch lengths in years, accounting for uncertainty in the first step. Currently, one limitation is that the tree topology needs to be known, and another limitation is that constraints need to be certain. Users of this method should be mindful of the latter when hundreds of constraints are used, as done by Szöllősi et al. (2021) to date the trees of Cyanobacteria and Archaea. Szöllősi et al. (2021)'s method is implemented in RevBayes, a highly modular platform for phylogenetic inference, rapidly growing in popularity (Höhna et al. 2016). The RevBayes tutorial page features a step-by-step tutorial "Dating with Relative Constraints", which makes the method highly approachable. References: Boni MF, Lemey P, Jiang X, Lam TT-Y, Perry BW, Castoe TA, Rambaut A, Robertson DL (2020) Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Microbiology, 5, 1408–1417. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0771-4 Davín AA, Tannier E, Williams TA, Boussau B, Daubin V, Szöllősi GJ (2018) Gene transfers can date the tree of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2, 904–909. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0525-3 Heath TA, Huelsenbeck JP, Stadler T (2014) The fossilized birth–death process for coherent calibration of divergence-time estimates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, E2957–E2966. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319091111 Höhna S, Landis MJ, Heath TA, Boussau B, Lartillot N, Moore BR, Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F (2016) RevBayes: Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference Using Graphical Models and an Interactive Model-Specification Language. Systematic Biology, 65, 726–736. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syw021 Magnabosco C, Moore KR, Wolfe JM, Fournier GP (2018) Dating phototrophic microbial lineages with reticulate gene histories. Geobiology, 16, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/gbi.12273 Nguyen JMT, Ho SYW (2020) Calibrations from the Fossil Record. In: The Molecular Evolutionary Clock: Theory and Practice (ed Ho SYW), pp. 117–133. Springer International Publishing, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60181-2_8 Szollosi, G.J., Hoehna, S., Williams, T.A., Schrempf, D., Daubin, V., Boussau, B. (2021) Relative time constraints improve molecular dating. bioRxiv, 2020.10.17.343889, ver. 8 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.17.343889 Wolfe JM, Fournier GP (2018) Horizontal gene transfer constrains the timing of methanogen evolution. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2, 897–903. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0513-7 | Relative time constraints improve molecular dating | Gergely J Szollosi, Sebastian Hoehna, Tom A Williams, Dominik Schrempf, Vincent Daubin, Bastien Boussau | <p style="text-align: justify;">Dating the tree of life is central to understanding the evolution of life on Earth. Molecular clocks calibrated with fossils represent the state of the art for inferring the ages of major groups. Yet, other informat... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Cécile Ané | 2020-10-21 23:39:17 | View | |

29 Nov 2023

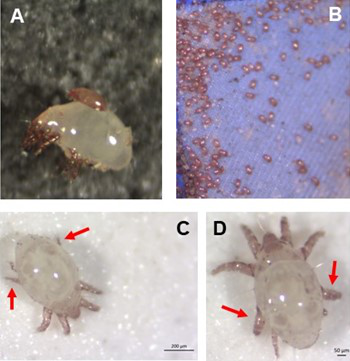

Individual differences in developmental trajectory leave a male polyphenic signature in bulb mite populationsJacques A. Deere & Isabel M. Smallegange https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.06.527265What determines whether to scramble or fight in male bulb mitesRecommended by Ulrich Karl Steiner based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

A classic textbook example in evolutionary ecology for phenotypic plasticity—the expression of different phenotypes by a genotype under different environmental conditions—is on Daphnia (Dodson 1989). If various species of this small crustacean are exposed to predation risk or cues thereof, their offspring show induced defense phenotypes including helmets, neck teeth, or head- and tail-spines. These induced morphological changes lower the risk of being eaten by a predator. As in Daphnia, induction can span over generations, while other induced phenotypic plastic changes are almost instantaneous, including many responses in physiology and behaviour (Gabriel et al. 2005). Larvae male bulb mites also show plasticity in morphologies throughout development. They can develop into a costly adult fighter morphology or a less costly, but vulnerable, scrambler type. The question Deere and Smallegange (Deere & Smallegange 2023) address is whether male bulb mite larvae can anticipate which type will likely be adaptive once they become adult, or alternatively, whether the resource availability or population density they experience during their larvae phase determines frequencies of adult scrambler and fighter types. They explore this question through experimental evolution, by removing different fractions of developing intermediate larva types. They thereby manipulate the stage structure of populations and alter selective forces on these stages. The potential shift of fixed genetics, imposed by the experimental selection regimes, is evaluated by fitness assays in green garden experiments. The exciting extension to classical experiments on phenotypic plasticity is that the authors aim at exploring eco-evolutionary feedbacks experimentally in a system that is a little more complex than basic host-parasite or predator-prey systems. The latter involve, for instance, rotifer-algae dynamics (Yoshida et al. 2003; Becks et al. 2012) or similar simple lab systems for which eco-evolutionary feedbacks have been demonstrated. The challenge for the exploration of more complex systems is revealed in the study by Deere and Smallegange. Their findings suggest that the frequencies of adult male morphotype is triggered by the environmental condition (nutrient availability) during the larval phase, i.e. a simple environmental induced plastic response. No fixed genetic shift in determining adult morphotype frequencies occurs. The trigger at the larva phase remains also not perfectly determined in their experiments, as population density and resource (food) availability are partly confounded. Additional complexity and selective aspects come into play in this system, as the targeted developmental stages that develop into fighter male morphs are also dispersal morphs. If selection on dispersal to avoid residing in food-limited environments is strong, triggering genetic shifts in fighter morphs by local population structure might be hard to experimentally achieve. Small sample sizes limit conclusions on complex interactions among duration of the experiment, population size, developmental stage types, and adult fighter frequencies. The presented study (Deere & Smallegange 2023) helps to bridge theoretical predictions and empirical evidence for eco-evolutionary feedbacks that goes beyond simple ecological-driven changes in population dynamics (Govaert et al. 2019).

References

Becks, L., Ellner, S.P., Jones, L.E. & Hairston, N.G. (2012). The functional genomics of an eco-evolutionary feedback loop: linking gene expression, trait evolution, and community dynamics. Ecol. Lett., 15, 492-501. | Individual differences in developmental trajectory leave a male polyphenic signature in bulb mite populations | Jacques A. Deere & Isabel M. Smallegange | <p style="text-align: justify;">Developmental plasticity alters phenotypes and can in that way change the response to selection. When alternative phenotypes show different life history trajectories, developmental plasticity can also affect, and be... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Phenotypic Plasticity, Sexual Selection | Ulrich Karl Steiner | 2023-02-07 12:14:33 | View | |

29 Nov 2022

Joint inference of adaptive and demographic history from temporal population genomic dataVitor A. C. Pavinato, Stéphane De Mita, Jean-Michel Marin, Miguel de Navascués https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.12.435133Inference of genome-wide processes using temporal population genomic dataRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio and 2 anonymous reviewersEvolutionary genomics, and population genetics in particular, aim to decipher the respective influence of neutral and selective forces shaping genetic polymorphism in a species/population. This is a much-needed requirement before scanning genome data for footprints of species adaptation to their biotic and abiotic environment (Johri et al. 2022). In general, we would like to quantify the proportion of the genome evolving neutrally and under selective (positive, balancing and negative) pressures (Kern and Hahn 2018, Johri et al. 2021). We thus need to understand patterns of linked selection along the genome, that is how the distribution of genetic polymorphisms is shaped by selected sites and the recombination landscape. The present contribution by Pavinato et al. (2022) provides an additional method in the population genomics toolbox to quantify the extent of linked positive and negative selection using temporal data. The availability of genomics data for model and non-model species has led to improvement of the modeling framework for demography and selection (Johri et al. 2022), but also new inference methods making use of the full genome data based on the Sequential Markovian Coalescent (SMC, Li and Durbin 2011), Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC, Jay et al. 2019), ABC and machine learning (Pudlo et al. 2016, Raynal et al. 2019) or Deep Learning (Sanchez et al. 2021). These methods are based on one sample in time and the use of the coalescent theory to reconstruct the past (demographic) history. However, it is also possible to obtain for many species temporal data sampled over several time points. For species with short generation time (in experimental evolution or monitored populations), one can sample a population every couple of generations as exemplified with Drosophila melanogaster (Bergland et al. 2010). For species with longer generation times that cannot be easily regularly sampled in time, it becomes possible to sequence available specimens from museums (e.g. Cridland et al. 2018) or ancient DNA samples. Methods using temporal data are based on the classical population genomics assumption that demography (migration, population subdivision, population size changes) leaves a genome-wide signal, while selection leaves a localized signal in the close vicinity of the causal mutation. Several methods do assess the demography of a population (change in effective population size, Ne, in time) using temporal data (e.g. Jorde and Ryman 2007) which can be used to calibrate the detection of loci under strong positive selection (Foll et al. 2014). Recently Buffalo and Coop (2020) used genome-wide covariance between allele frequency changes across time samples (and across replicates) to quantify the effects of linked selection over short timescales. In the present contribution, Pavinato et al. (2022) make use of temporal data to draw the joint estimation of demographic and selective parameters using a simulation-based method (ABC-Random Forests). This study by Pavinato et al. (2022) builds a framework allowing to infer the census size of the population in time (N) separately from the effect of genetic drift, which is determined by change in effective population size (Ne) in time, as well estimates of genome-wide parameters of selection. In a nutshell, the authors use a forward simulator and summarize genome data by genomic windows using classic statistics (nucleotide diversity, Tajima’s D, FST, heterozygosity) between time samples and for each sample. They specifically use the distributions (higher moments) of these statistics among all windows. The authors combine as input for the ABC-RF, vectors of summary statistics, model parameters and five latent variables: Ne, the ratio Ne/N, the number of beneficial mutations under strong selection, the average selection coefficient of strongly selected mutations, and the average substitution load. Indeed, the authors are interested in three different types of selection components: 1) the adaptive potential of a population which is estimated as the population mutation rate of beneficial mutations (θb), 2) the number of mutations under strong selection (irrespective of whether they reached fixation or not), and 3) the overall population fitness which is a function of the genetic load. In other words, the novelty of this method is not to focus on the detection of loci under selection, but to infer key parameters/distributions summarizing the genome-wide signal of demography and (positive and negative) selection. As a proof of principle, the authors then apply their method to a dataset of feral populations of honey bees (Apis mellifera) collected in California across many years and recovered from Museum samples (Cridland et al. 2018). The approach yields estimates of Ne which are on the same order of magnitude of previous estimates in hymenopterans, and the authors discuss why the different populations show various values of Ne and N which can be explained by different history of admixture with wild but also domesticated lineages of bees. This study focuses on quantifying the genome-wide joint footprints of demography, and strong positive and negative selection to determine which proportion of the genome evolves neutrally or not. Further application of this method can be anticipated, for example, to study species with ecological and life-history traits which generate discrepancies between census size and Ne, for example for plants with selfing or seed banking (Sellinger et al. 2020), and for which the genome-wide effect of linked selection is not fully understood. References Johri P, Aquadro CF, Beaumont M, Charlesworth B, Excoffier L, Eyre-Walker A, Keightley PD, Lynch M, McVean G, Payseur BA, Pfeifer SP, Stephan W, Jensen JD (2022) Recommendations for improving statistical inference in population genomics. PLOS Biology, 20, e3001669. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001669 Kern AD, Hahn MW (2018) The Neutral Theory in Light of Natural Selection. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1366–1371. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy092 Johri P, Riall K, Becher H, Excoffier L, Charlesworth B, Jensen JD (2021) The Impact of Purifying and Background Selection on the Inference of Population History: Problems and Prospects. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 38, 2986–3003. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab050 Pavinato VAC, Mita SD, Marin J-M, Navascués M de (2022) Joint inference of adaptive and demographic history from temporal population genomic data. bioRxiv, 2021.03.12.435133, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.12.435133 Li H, Durbin R (2011) Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature, 475, 493–496. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10231 Jay F, Boitard S, Austerlitz F (2019) An ABC Method for Whole-Genome Sequence Data: Inferring Paleolithic and Neolithic Human Expansions. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 36, 1565–1579. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msz038 Pudlo P, Marin J-M, Estoup A, Cornuet J-M, Gautier M, Robert CP (2016) Reliable ABC model choice via random forests. Bioinformatics, 32, 859–866. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv684 Raynal L, Marin J-M, Pudlo P, Ribatet M, Robert CP, Estoup A (2019) ABC random forests for Bayesian parameter inference. Bioinformatics, 35, 1720–1728. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty867 Sanchez T, Cury J, Charpiat G, Jay F (2021) Deep learning for population size history inference: Design, comparison and combination with approximate Bayesian computation. Molecular Ecology Resources, 21, 2645–2660. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13224 Bergland AO, Behrman EL, O’Brien KR, Schmidt PS, Petrov DA (2014) Genomic Evidence of Rapid and Stable Adaptive Oscillations over Seasonal Time Scales in Drosophila. PLOS Genetics, 10, e1004775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004775 Cridland JM, Ramirez SR, Dean CA, Sciligo A, Tsutsui ND (2018) Genome Sequencing of Museum Specimens Reveals Rapid Changes in the Genetic Composition of Honey Bees in California. Genome Biology and Evolution, 10, 458–472. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evy007 Jorde PE, Ryman N (2007) Unbiased Estimator for Genetic Drift and Effective Population Size. Genetics, 177, 927–935. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.107.075481 Foll M, Shim H, Jensen JD (2015) WFABC: a Wright–Fisher ABC-based approach for inferring effective population sizes and selection coefficients from time-sampled data. Molecular Ecology Resources, 15, 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12280 Buffalo V, Coop G (2020) Estimating the genome-wide contribution of selection to temporal allele frequency change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117, 20672–20680. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1919039117 Sellinger TPP, Awad DA, Moest M, Tellier A (2020) Inference of past demography, dormancy and self-fertilization rates from whole genome sequence data. PLOS Genetics, 16, e1008698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008698 | Joint inference of adaptive and demographic history from temporal population genomic data | Vitor A. C. Pavinato, Stéphane De Mita, Jean-Michel Marin, Miguel de Navascués | <p style="text-align: justify;">Disentangling the effects of selection and drift is a long-standing problem in population genetics. Simulations show that pervasive selection may bias the inference of demography. Ideally, models for the inference o... |  | Adaptation, Population Genetics / Genomics | Aurelien Tellier | 2021-10-20 09:41:26 | View | |

06 Mar 2023

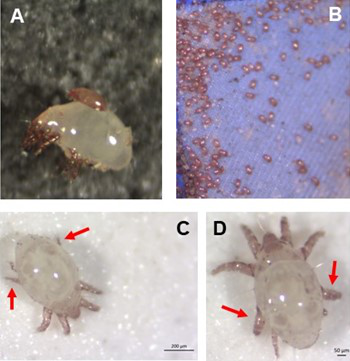

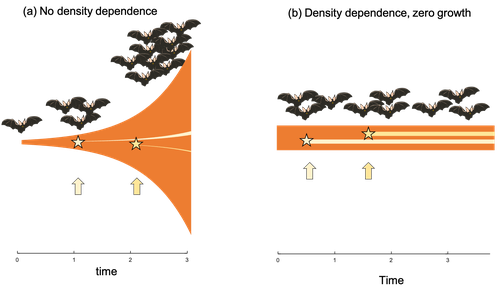

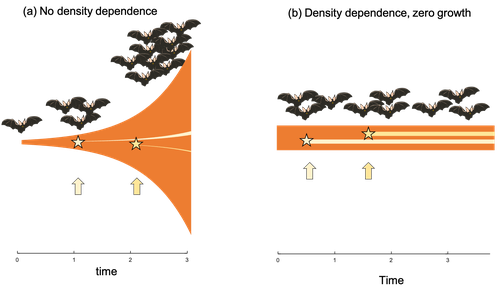

Extrinsic mortality and senescence: a guide for the perplexedCharlotte de Vries, Matthias Galipaud, Hanna Kokko https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.27.478060Getting old gracefully, and risk of dying before getting there: a new guide to theory on extrinsic mortality and senescenceRecommended by Sinead English and Shinichi Nakagawa based on reviews by Nicole Walasek and 1 anonymous reviewerWhy is there such variation across species and populations in the rate at which individuals show wear and tear as they get older? Several compelling theoretical explanations have been developed on the conditions under which selection allows for or prevents senescence; a notable one being that proposed by George C Williams in 1957 based on the idea of antagonistic pleiotropy (Williams, 1957). One of the testable predictions of this theory is that, in populations where adults experience higher mortality, senescence is expected to be faster. This is one of the most influential predictions of the paper, being intuitive (when individuals are less likely to survive to later age classes, we expect weakened selection on traits that would avoid senescence in these classes), and fitting with ‘live fast, die young’ life history framing. As such, it has been widely incorporated into how we think about the evolution of senescence and has received considerable support in comparative studies across species and populations. However, it would be misleading to sit back at this point and think we have ‘solved’ the problem of understanding variation in senescence, and how this is linked with mortality. It turns out that the Williams 1957 paper is hotly contested by theoreticians: for the past 30 years – with increasing focus in the last 4 years – a growing body of models and opinion pieces have proposed flaws in the paper itself and in how it has been interpreted (Abrams, 1993; André and Rousset, 2020; Day and Abrams, 2020; Moorad et al., 2019). Central to several of these critiques is that explicit consideration of density dependence (not considered in Williams’ original paper) changes the conditions under which his predictions hold. A new preprint by de Vries, Gallipaud and Kokko brings further clarity to such critiques of the original paper (Vries et al., 2023). Beyond just continuing the tradition of critiquing Williams’ prediction, however, de Vries et al. provide a clear guide that is accessible to non-theoreticians about the issues with William’s prediction, and the way in which density dependence and how it operates can change when we expect senescence to occur. Rather than reiterate their points here, we suggest a close reading of the paper itself, along with an excellent overview of the paper in a recent blog by Daniel Nettle (Nettle, 2022). In brief, the paper starts by synthesizing earlier theoretical and empirical studies on the topic and presenting a very simple model to highlight how – in the absence of density dependence – Williams’ prediction does not hold because of the unregulated population growth, which is necessarily higher when there is low mortality. As a result, for a lineage with low mortality, any fitness advantage of placing offspring into the lineage later (i.e. selection for reduced senescence) is exactly cancelled out by the fact that earlier-produced offspring have higher fitness returns. They then present a more complex framework, which incorporates realistic mortality distributions, trade-offs between survival and reproduction, and use a series of 10 scenarios of density dependence (and whether this acts on survival or fecundity, and also whether it depends on a threshold or stochastic, or exerts continuing pressure on the trait) to explore selection on fitness-associated traits with age depending on extrinsic mortality. This then generates a range of results for when the Williams prediction holds, when there is no link between mortality and senescence, and when there is an ‘anti-Williams’ result – i.e., where senescence is slower when there is a high mortality. As has been shown in earlier studies, density dependence and how it operates matters, and Williams’ prediction holds most when density dependence affects juvenile age classes (in their model, when adults are less likely to produce them – i.e. there is density dependence on fecundity; or when there is less recruitment into the adult population due to, for example, competition among juveniles). So, perhaps we are now at a point where we can lay to rest the debate on the issues specifically with Williams’ original paper, and instead consider more broadly the key factors to measure when predicting patterns of senescence, and what is tangible for empiricists to quantify in their studies. Here, de Vries et al. provide some helpful insights both into the limitations of their approach and what modelling should be done moving forward, and into how we can link existing studies (for example comparing senescence among populations with varying predation pressure) to the theoretical predictions. At the heart of the latter is understanding the mechanism of density-dependent regulation – does it affect survival or fecundity, which age classes are most sensitive, and how do key traits depend on density? – and this is often difficult to measure in field studies. And from all this we can learn that even very intuitive and extensively discussed concepts in biology do not always have as firm theoretical underpinnings as assumed, and – as should not be surprising – biology is complex and rather than one clear pattern being predicted, this can depend on a multitude of factors. REFERENCES Abrams PA (1993) Does increased mortality favor the evolution of more rapid senescence? Evolution, 47, 877–887. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb01241.x André J-B, Rousset F (2020) Does extrinsic mortality accelerate the pace of life? A bare-bones approach. Evolution and Human Behavior, 41, 486–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.03.002 Day T, Abrams PA (2020) Density Dependence, Senescence, and Williams’ Hypothesis. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35, 300–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.11.005 Moorad J, Promislow D, Silvertown J (2019) Evolutionary Ecology of Senescence and a Reassessment of Williams’ ‘Extrinsic Mortality’ Hypothesis. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34, 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.02.006 Nettle AD (2022) Live fast and die young (maybe). https://www.danielnettle.org.uk/2022/02/18/live-fast-and-die-young-maybe/ (accessed 2.27.23). de Vries C, Galipaud M, Kokko H (2023) Extrinsic mortality and senescence: a guide for the perplexed. bioRxiv, 2022.01.27.478060, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.27.478060 Williams GC (1957) Pleiotropy, natural selection, and the evolution of senescence. Evolution, 11, 398–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1957.tb02911.x | Extrinsic mortality and senescence: a guide for the perplexed | Charlotte de Vries, Matthias Galipaud, Hanna Kokko | <p style="text-align: justify;">Do environments or species traits that lower the mortality of individuals create selection for delaying senescence? Reading the literature creates an impression that mathematically oriented biologists cannot agree o... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Life History | Sinead English | 2022-08-26 14:30:16 | View | |

18 Nov 2022

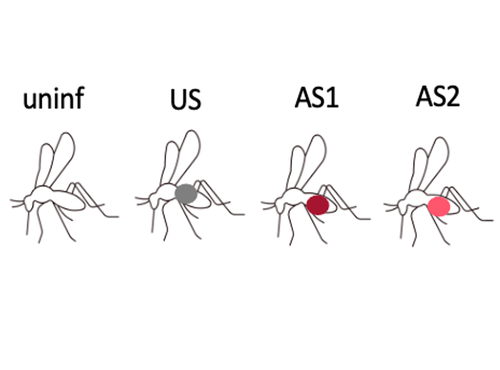

Fitness costs and benefits in response to artificial artesunate selection in PlasmodiumVilla M, Berthomieu A, Rivero A https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.28.478164The importance of understanding fitness costs associated with drug resistance throughout the life cycle of malaria parasitesRecommended by Silvie Huijben based on reviews by Sarah Reece and Marianna SzucsAntimalarial resistance is a major hurdle to malaria eradication efforts. The spread of drug resistance follows basic evolutionary principles, with competitive interactions between resistant and susceptible malaria strains being central to the fitness of resistant parasites. These competitive interactions can be used to design resistance management strategies, whereby a fitness cost of resistant parasites can be exploited through maintaining competitive suppression of the more fit drug-susceptible parasites. This can potentially be achieved using lower drug dosages or lower frequency of drug treatments. This approach has been demonstrated to work empirically in a rodent malaria model [1,2] and has been demonstrated to have clinical success in cancer treatments [3]. However, these resistance management approaches assume a fitness cost of the resistant pathogen, and, in the case of malaria parasites in general, and for artemisinin resistant parasites in particular, there is limited information on the presence of such fitness cost. The best suggestive evidence for the presence of fitness costs comes from the discontinuation of the use of the drug, which, in the case of chloroquine, was followed by a gradual drop in resistance frequency over the following decade [see e.g. 4,5]. However, with artemisinin derivative drugs still in use, alternative ways to study the presence of fitness costs need to be undertaken. References [1] Huijben S, Bell AS, Sim DG, Tomasello D, Mideo N, Day T, et al. 2013. Aggressive chemotherapy and the selection of drug resistant pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 9(9): e1003578. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003578 [5] Mharakurwa S, Matsena-Zingoni Z, Mudare N, Matimba C, Gara TX, Makuwaza A, et al. 2021. Steep rebound of chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum in Zimbabwe. J Infect Dis. 223(2): 306-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa368 | Fitness costs and benefits in response to artificial artesunate selection in Plasmodium | Villa M, Berthomieu A, Rivero A | <p style="text-align: justify;">Drug resistance is a major issue in the control of malaria. Mutations linked to drug resistance often target key metabolic pathways and are therefore expected to be associated with biological costs. The spread of dr... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Life History | Silvie Huijben | 2022-01-31 13:01:16 | View | |

30 Jun 2023

How do monomorphic bacteria evolve? The Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and the awkward population genetics of extreme clonalityChristoph Stritt, Sebastien Gagneux https://doi.org/10.32942/X2GW2PHow the tubercle bacillus got its genome: modernising, modelling, and making sense of the stories we tellRecommended by B. Jesse Shapiro based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersIn this instructive review, Stritt and Gagneux offer a balanced perspective on the evolutionary forces shaping Mycobacterium tuberculosis and make the case that our instinct for storytelling be balanced with quantitative models. M. tuberculosis is perhaps the best-known clonal bacterial pathogen – evolving largely in the absence of horizontal gene transfer. Its genome is full of puzzling patterns, including much higher GC content than most intracellular pathogens (which suggests efficient selection to resist AT-skewed mutational bias) but a very high ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rates (dN/dS ~ 0.5, typically interpreted as weak selection against deleterious amino acid changes). The authors offer alternative explanations for these patterns, framing the question: is M. tuberculosis evolution shaped mainly by drift or by efficient selection? They propose that this question can only be answered by accounting for the pathogen’s extreme clonality. A clonal lifestyle can have its advantages, for example when adaptations must arise in a particular order (Kondrashov and Kondrashov 2001). An important disadvantage highlighted by the authors are linkage effects: without recombination to shuffle them up, beneficial mutations are linked to deleterious mutations in the same genome (hitchhiking) and purging deleterious mutations also purges neutral diversity across the genome (background selection). The authors propose the latter – efficient purifying selection and strong linkage – as an explanation for the low genetic diversity observed in M. tuberculosis. This is of course not exclusive of other related explanations, such as clonal interference (Gerrish and Lenski 1998). They also champion the use of forward evolutionary simulations (Haller and Messer 2019) to model the interplay between selection, recombination, and demography as a powerful alternative to traditional backward coalescent models. At times, Stritt and Gagneux are pessimistic about our existing methods – arguing that dN/dS and homoplasies “tell us little about the frequency and strength of selection.” Even though I favour a more optimistic view, I fully agree that our traditional population genetic metrics are sensitive to a slew of different deviations from a standard neutral evolution model and must be interpreted with caution. As I and others have argued, the extent of recombination (measured as the amount of linkage in a genome) is a key factor in determining how best to test for natural selection (Shapiro et al. 2009) and to conduct genotype-phenotype association studies (Chen and Shapiro 2021) in microbes. While this article is focused on the well-studied M. tuberculosis complex, there are many parallels with other clonal bacteria, including pathogens and symbionts. Whatever your favourite bug, we must all be careful to make sure the stories we tell about them are not “just so tales” but are supported, to the extent possible, by data and quantitative models. References Chen, Peter E., and B. Jesse Shapiro. 2021. "Classic Genome-Wide Association Methods Are Unlikely to Identify Causal Variants in Strongly Clonal Microbial Populations." bioRxiv. Stritt, C., Gagneux, S. (2023). How do monomorphic bacteria evolve? The Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and the awkward population genetics of extreme clonality. EcoEvoRxiv, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2GW2P | How do monomorphic bacteria evolve? The *Mycobacterium tuberculosis* complex and the awkward population genetics of extreme clonality | Christoph Stritt, Sebastien Gagneux | <p style="text-align: justify;">Exchange of genetic material through sexual reproduction or horizontal gene transfer is ubiquitous in nature. Among the few outliers that rarely recombine and mainly evolve by <em>de novo</em> mutation are a group o... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | B. Jesse Shapiro | Gonçalo Themudo | 2022-12-16 13:41:53 | View |

02 Sep 2022

Introgression between highly divergent sea squirt genomes: an adaptive breakthrough?Christelle Fraïsse, Alan Le Moan, Camille Roux, Guillaume Dubois, Claire Daguin-Thiébaut, Pierre-Alexandre Gagnaire, Frédérique Viard, Nicolas Bierne https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.22.485319A match made in the Anthropocene: human-mediated adaptive introgression across a speciation continuumRecommended by Fernando Racimo based on reviews by Michael Westbury, Andrew Foote and Erin CalfeeThe long-distance transport and introduction of new species by humans is increasingly leading divergent lineages to interact, and sometimes interbreed, even after thousands or millions of years of separation. It is thus of prime importance to understand the consequences of these contemporary admixture events on the evolutionary fitness of interacting organisms, and their ecological implications. Ciona robusta and Ciona intestinalis are two species of sea squirts that diverged between 1.5 and 2 million years ago and recently came into contact again. This occurred through human-mediated introduction of C. robusta (native to the Northwest Pacific) into the range of C. intestinalis (the English channeled Northeast Atlantic). In this study, Fraïsse et al. (2022) follow up on earlier work by Le Moan et al. (2021), who had identified a long genomic hotspot of introgression of C. robusta ancestry segments in chromosome 5 of C. intestinalis. The hotspot bears suggestive evidence of positive selection and the authors aimed to investigate this further using fully phased whole-genome sequences. The authors narrow down on the exact boundaries of the introgressed region, and make a compelling case that it has been the likely target of positive selection after introgression, using various complementary approaches based on patterns of population differentiation, haplotype structure and local levels of diversity in the region. Using extensive demographic modeling, they also show that the introgression event was likely recent (approximately 75 years ago), and distinct from other tracts in the C. intestinalis genome that are likely a product of more ancient episodes of interbreeding in the past 30,000 years. Narrowing down on the potential drivers of selection, the authors show that candidate SNPs in the region overlap with the cytochrome family 2 subfamily U gene - involved in the detoxification of exogenous compounds - potentially reflecting adaptation to chemicals encountered in the sea squirt's environment. There also appears to be copy number variation at the candidate SNPs, which provides clues into the adaptation mechanism in the region. All reviewers agreed that the work carried out by the authors is elegant and the results are robustly supported and well presented. In a round of reviews, various clarifications of the manuscript were suggested by the reviewers, including on the quality of the newly generated sequencing data, and some suggestions for qualifications on the conclusions reached by the authors as well as changes in the figures to increase their clarity. The authors addressed the different concerns of the reviewers, and the new version is much improved. This study into human-mediated introgression and its consequences for adaptation is, in my view, both well thought-out and executed. I therefore provide an enthusiastic recommendation of this manuscript. References Fraïsse C, Le Moan A, Roux C, Dubois G, Daguin-Thiébaut C, Gagnaire P-A, Viard F and Bierne N (2022) Introgression between highly divergent sea squirt genomes: an adaptive breakthrough? bioRxiv, 2022.03.22.485319, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.22.485319 Le Moan A, Roby C, Fraïsse C, Daguin-Thiébaut C, Bierne N, Viard F (2021) An introgression breakthrough left by an anthropogenic contact between two ascidians. Molecular Ecology, 30, 6718–6732. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16189 | Introgression between highly divergent sea squirt genomes: an adaptive breakthrough? | Christelle Fraïsse, Alan Le Moan, Camille Roux, Guillaume Dubois, Claire Daguin-Thiébaut, Pierre-Alexandre Gagnaire, Frédérique Viard, Nicolas Bierne | <p style="text-align: justify;">Human-mediated introductions are reshuffling species distribution on a global scale. Consequently, an increasing number of allopatric taxa are now brought into contact, promoting introgressive hybridization between ... |  | Adaptation, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics | Fernando Racimo | 2022-04-14 15:30:42 | View | |

17 Jun 2022

Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process?Claire Capdevielle Dulac, Romain Benoist, Sarah Paquet, Paul-André Calatayud, Julius Obonyo, Laure Kaiser, Florence Mougel https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.13.472356The potential evolutionary importance of low-frequency flexibility in reproductive modesRecommended by Christoph Haag based on reviews by Michael Lattorff and Jens BastOccasional events of asexual reproduction in otherwise sexual taxa have been documented since a long time. Accounts range from observations of offspring development from unfertilized eggs in Drosophila to rare offspring production by isolated females in lizards and birds (e.g., Stalker 1954, Watts et al 2006, Ryder et al. 2021). Many more such cases likely await documentation, as rare events are inherently difficult to observe. These rare events of asexual reproduction are often associated with low offspring fitness (“tychoparthenogenesis”), and have mostly been discarded in the evolutionary literature as reproductive accidents without evolutionary significance. Recently, however, there has been an increased interest in the details of evolutionary transitions from sexual to asexual reproduction (e.g., Archetti 2010, Neiman et al.2014, Lenormand et al. 2016), because these details may be key to understanding why successful transitions are rare, why they occur more frequently in some groups than in others, and why certain genetic mechanisms of ploidy maintenance or ploidy restoration are more often observed than others. In this context, the hypothesis has been formulated that regular or even obligate asexual reproduction may evolve from these rare events of asexual reproduction (e.g., Schwander et al. 2010). A new study by Capdevielle Dulac et al. (2022) now investigates this question in a parasitoid wasp, highlighting also the fact that what is considered rare or occasional may differ from one system to the next. The results show “rare” parthenogenetic production of diploid daughters occurring at variable frequencies (from zero to 2 %) in different laboratory strains, as well as in a natural population. They also demonstrate parthenogenetic production of female offspring in both virgin females and mated ones, as well as no reduced fecundity of parthenogenetically produced offspring. These findings suggest that parthenogenetic production of daughters, while still being rare, may be a more regular and less deleterious reproductive feature in this species than in other cases of occasional asexuality. Indeed, haplodiploid organisms, such as this parasitoid wasp have been hypothesized to facilitate evolutionary transitions to asexuality (Neimann et al. 2014, Van Der Kooi et al. 2017). First, in haploidiploid organisms, females are diploid and develop from normal, fertilized eggs, but males are haploid as they develop parthenogenetically from unfertilized eggs. This means that, in these species, fertilization is not necessarily needed to trigger development, thus removing one of the constraints for transitions to obligate asexuality (Engelstädter 2008, Vorburger 2014). Second, spermatogenesis in males occurs by a modified meiosis that skips the first meiotic division (e.g., Ferree et al. 2019). Haploidiploid organisms may thus have a potential route for an evolutionary transition to obligate parthenogenesis that is not available to organisms: The pathways for the modified meiosis may be re-used for oogenesis, which might result in unreduced, diploid eggs. Third, the particular species studied here regularly undergoes inbreeding by brother-sister mating within their hosts. Homozygosity, including at the sex determination locus (Engelstädter 2008), is therefore expected to have less negative effects in this species compared to many other, non-inbreeding haplodipoids (see also Little et al. 2017). This particular species may therefore be less affected by loss of heterozygosity, which occurs in a fashion similar to self-fertilization under many forms of non-clonal parthenogenesis. Indeed, the study also addresses the mechanisms underlying parthenogenesis in the species. Surprisingly, the authors find that parthenogenetically produced females are likely produced by two distinct genetic mechanisms. The first results in clonality (maintenance of the maternal genotype), whereas the second one results in a loss of heterozygosity towards the telomeres, likely due to crossovers occurring between the centromeres and the telomeres. Moreover, bacterial infections appear to affect the propensity of parthenogenesis but are unlikely the primary cause. Together, the finding suggests that parthenogenesis is a variable trait in the species, both in terms of frequency and mechanisms. It is not entirely clear to what degree this variation is heritable, but if it is, then these results constitute evidence for low-frequency existence of variable and heritable parthenogenesis phenotypes, that is, the raw material from which evolutionary transitions to more regular forms of parthenogenesis may occur.

References Archetti M (2010) Complementation, Genetic Conflict, and the Evolution of Sex and Recombination. Journal of Heredity, 101, S21–S33. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esq009 Capdevielle Dulac C, Benoist R, Paquet S, Calatayud P-A, Obonyo J, Kaiser L, Mougel F (2022) Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process? bioRxiv, 2021.12.13.472356, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.13.472356 Engelstädter J (2008) Constraints on the evolution of asexual reproduction. BioEssays, 30, 1138–1150. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.20833 Ferree PM, Aldrich JC, Jing XA, Norwood CT, Van Schaick MR, Cheema MS, Ausió J, Gowen BE (2019) Spermatogenesis in haploid males of the jewel wasp Nasonia vitripennis. Scientific Reports, 9, 12194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48332-9 van der Kooi CJ, Matthey-Doret C, Schwander T (2017) Evolution and comparative ecology of parthenogenesis in haplodiploid arthropods. Evolution Letters, 1, 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.30 Lenormand T, Engelstädter J, Johnston SE, Wijnker E, Haag CR (2016) Evolutionary mysteries in meiosis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371, 20160001. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0001 Little CJ, Chapuis M-P, Blondin L, Chapuis E, Jourdan-Pineau H (2017) Exploring the relationship between tychoparthenogenesis and inbreeding depression in the Desert Locust, Schistocerca gregaria. Ecology and Evolution, 7, 6003–6011. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3103 Neiman M, Sharbel TF, Schwander T (2014) Genetic causes of transitions from sexual reproduction to asexuality in plants and animals. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 27, 1346–1359. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12357 Ryder OA, Thomas S, Judson JM, Romanov MN, Dandekar S, Papp JC, Sidak-Loftis LC, Walker K, Stalis IH, Mace M, Steiner CC, Chemnick LG (2021) Facultative Parthenogenesis in California Condors. Journal of Heredity, 112, 569–574. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esab052 Schwander T, Vuilleumier S, Dubman J, Crespi BJ (2010) Positive feedback in the transition from sexual reproduction to parthenogenesis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277, 1435–1442. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.2113 Stalker HD (1954) Parthenogenesis in Drosophila. Genetics, 39, 4–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/39.1.4 Vorburger C (2014) Thelytoky and Sex Determination in the Hymenoptera: Mutual Constraints. Sexual Development, 8, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356508 Watts PC, Buley KR, Sanderson S, Boardman W, Ciofi C, Gibson R (2006) Parthenogenesis in Komodo dragons. Nature, 444, 1021–1022. https://doi.org/10.1038/4441021a | Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process? | Claire Capdevielle Dulac, Romain Benoist, Sarah Paquet, Paul-André Calatayud, Julius Obonyo, Laure Kaiser, Florence Mougel | <p style="text-align: justify;">Hymenopterans are haplodiploids and unlike most other Arthropods they do not possess sexual chromosomes. Sex determination typically happens via the ploidy of individuals: haploids become males and diploids become f... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Reproduction and Sex | Christoph Haag | 2021-12-16 15:25:16 | View | |

25 Jan 2024

Sperm production and allocation in response to risk of sperm competition in the black soldier fly Hermetia illucensFrédéric Manas, Carole Labrousse, Christophe Bressac https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.20.544772Elevated sperm production and faster transfer: plastic responses to the risk of sperm competition in males of the black sodier fly Hermetia illuceRecommended by Trine Bilde based on reviews by Rebecca Boulton, Isabel Smallegange and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Rebecca Boulton, Isabel Smallegange and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this paper (Manas et al., 2023), the authors investigate male responses to risk of sperm competition in the black soldier fly Hermetia illuce, a widespread insect that has gained recent attention for its potential to be farmed for sustainable food production (Tomberlin & van Huis, 2020). Using an experimental approach that simulated low-risk (males were kept individually) and high-risk (males were kept in groups of 10) of sperm competition, they found that males reared in groups showed a significant increase in sperm production compared with males reared individually. This shows a response to the rearing environment in sperm production that is consistent with an increase in the perceived risk of sperm competition. These males were then used in mating experiments to determine whether sperm allocation to females during mating was influenced by the perceived risk of sperm competition. Mating experiments were initiated in groups, since mating only occurs when more than one male and one female are present, indicating strong sexual selection in the wild. Once a copulation began, the pair was moved to a new environment with no competition, with male competitors, or with other females, to test how social environment and potentially the sex of surrounding individuals influenced sperm allocation during mating. Copulation duration and the number of sperm transferred were subsequently counted. In these mating experiments, the number of sperm stored in the female spermathecae increased under immediate risk of sperm competition. Interestingly, this was not because males copulated for longer depending on the risk of sperm competition, indicating that males respond plastically to the risk of competition by elevating their investment in sperm production and speed of sperm transfer. There was no difference between competitive environments consisting of males or females respectively, suggesting that it is the presence of other flies per se that influence sperm allocation. The study provides an interesting new example of how males alter reproductive investment in response to social context and sexual competition in their environment. In addition, it provides new insights into the reproductive biology of the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens, which may be relevant for optimizing farming conditions. References Manas F, Labrousse C, Bressac C (2023) Sperm production and allocation in response to risks of sperm competition in the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens. bioRxiv, 2023.06.20.544772, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.20.544772 Tomberlin JK, Van Huis A (2020) Black soldier fly from pest to ‘crown jewel’ of the insects as feed industry: an historical perspective. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 6, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.3920/JIFF2020.0003 | Sperm production and allocation in response to risk of sperm competition in the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens | Frédéric Manas, Carole Labrousse, Christophe Bressac | <p style="text-align: justify;">In polyandrous species, competition between males for offspring paternity goes on after copulation through the competition of their ejaculates for the fertilisation of female's oocytes. Given that males allocating m... | Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Trine Bilde | 2023-06-26 09:41:07 | View | ||

12 Jun 2018

Transgenerational cues about local mate competition affect offspring sex ratios in the spider mite Tetranychus urticaeAlison B. Duncan, Cassandra Marinosci, Céline Devaux, Sophie Lefèvre, Sara Magalhães, Joanne Griffin, Adeline Valente, Ophélie Ronce, Isabelle Olivieri https://doi.org/10.1101/240127Maternal effects in sex-ratio adjustmentRecommended by Dries Bonte based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersOptimal sex ratios have been topic of extensive studies so far. Fisherian 1:1 proportions of males and females are known to be optimal in most (diploid) organisms, but many deviations from this golden rule are observed. These deviations not only attract a lot of attention from evolutionary biologists but also from population ecologists as they eventually determine long-term population growth. Because sex ratios are tightly linked to fitness, they can be under strong selection or plastic in response to changing demographic conditions. Hamilton [1] pointed out that an equality of the sex ratio breaks down when there is local competition for mates. Competition for mates can be considered as a special case of local resource competition. In short, this theory predicts females to adjust their offspring sex ratio conditional on cues indicating the level of local mate competition that their sons will experience. When cues indicate high levels of LMC mothers should invest more resources in the production of daughters to maximise their fitness, while offspring sex ratios should be closer to 50:50 when cues indicate low levels of LMC. References [1] Hamilton, W. D. (1967). Extraordinary Sex Ratios. Science, 156(3774), 477–488. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3774.477 | Transgenerational cues about local mate competition affect offspring sex ratios in the spider mite Tetranychus urticae | Alison B. Duncan, Cassandra Marinosci, Céline Devaux, Sophie Lefèvre, Sara Magalhães, Joanne Griffin, Adeline Valente, Ophélie Ronce, Isabelle Olivieri | <p style="text-align: justify;">In structured populations, competition between closely related males for mates, termed Local Mate Competition (LMC), is expected to select for female-biased offspring sex ratios. However, the cues underlying sex all... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Dries Bonte | 2017-12-29 16:10:32 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer