Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

03 Aug 2017

POSTPRINT

Fisher's geometrical model and the mutational patterns of antibiotic resistance across dose gradientsNoémie Harmand, Romain Gallet, Roula Jabbour-Zahab, Guillaume Martin, Thomas Lenormand 10.1111/evo.13111What doesn’t kill us makes us stronger: can Fisher’s Geometric model predict antibiotic resistance evolution?Recommended by Inês Fragata and Claudia BankThe increasing number of reported cases of antibiotic resistance is one of today’s major public health concerns. Dealing with this threat involves understanding what drives the evolution of antibiotic resistance and investigating whether we can predict (and subsequently avoid or circumvent) it [1]. References [1] Palmer AC, and Kishony R. 2013. Understanding, predicting and manipulating the genotypic evolution of antibiotic resistance. Nature Review Genetics 14: 243—248. doi: 10.1038/nrg3351 [2] Tenaillon O. 2014. The utility of Fisher’s geometric model in evolutionary genetics. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 45: 179—201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-120213-091846 [3] Blanquart F and Bataillon T. 2016. Epistasis and the structure of fitness landscapes: are experimental fitness landscapes compatible with Fisher’s geometric model? Genetics 203: 847—862. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.182691 [4] Harmand N, Gallet R, Jabbour-Zahab R, Martin G and Lenormand T. 2017. Fisher’s geometrical model and the mutational patterns of antibiotic resistance across dose gradients. Evolution 71: 23—37. doi: 10.1111/evo.13111 [5] de Visser, JAGM, and Krug J. 2014. Empirical fitness landscapes and the predictability of evolution. Nature 15: 480—490. doi: 10.1038/nrg3744 [6] Palmer AC, Toprak E, Baym M, Kim S, Veres A, Bershtein S and Kishony R. 2015. Delayed commitment to evolutionary fate in antibiotic resistance fitness landscapes. Nature Communications 6: 1—8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8385 | Fisher's geometrical model and the mutational patterns of antibiotic resistance across dose gradients | Noémie Harmand, Romain Gallet, Roula Jabbour-Zahab, Guillaume Martin, Thomas Lenormand | Fisher's geometrical model (FGM) has been widely used to depict the fitness effects of mutations. It is a general model with few underlying assumptions that gives a large and comprehensive view of adaptive processes. It is thus attractive in sever... |  | Adaptation | Inês Fragata | 2017-08-01 16:06:02 | View | |

03 Jun 2018

Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive conceptThomas Lenormand, Noemie Harmand, Romain Gallet https://doi.org/10.1101/276675Let’s move beyond costs of resistance!Recommended by Inês Fragata and Claudia Bank based on reviews by Danna Gifford, Helen Alexander and 1 anonymous reviewerThe increase in the prevalence of (antibiotic) resistance has become a major global health concern and is an excellent example of the impact of real-time evolution on human society. This has led to a boom of studies that investigate the mechanisms and factors involved in the evolution of resistance, and to the spread of the concept of "costs of resistance". This concept refers to the relative fitness disadvantage of a drug-resistant genotype compared to a non-resistant reference genotype in the ancestral (untreated) environment. In their paper, Lenormand et al. [1] discuss the history of this concept and highlight its caveats and limitations. The authors address both practical and theoretical problems that arise from the simplistic view of "costly resistance" and argue that they can be prejudicial for antibiotic resistance studies. For a better understanding, they visualize their points of critique by means of Fisher's Geometric model. The authors give an interesting historical overview of how the concept arose and speculate that it emerged (during the 1980s) in an attempt by ecologists to spread awareness that fitness can be environment-dependent, and because of the concept's parallels to trade-offs in life-history evolution. They then identify several problems that arise from the concept, which, besides the conceptual misunderstandings that they can cause, are important to keep in mind when designing experimental studies. The authors highlight and explain the following points: Lenormand et al.'s paper [1] is a timely perspective piece in light of the ever-increasing efforts to understand and tackle resistance evolution [2]. Although some readers may shy away from the rather theoretical presentation of the different points of concern, it will be useful for both theoretical and empirical readers by illustrating the misconceptions that can arise from the concept of the cost of resistance. Ultimately, the main lesson to be learned from this paper may not be to ban the term "cost of resistance" from one's vocabulary, but rather to realize that the successful fight against drug resistance requires more differential information than the measurement of fitness effects in a drug-treated vs. non-treated environment in the lab [3-4]. Specifically, a better integration of the ecological aspects of drug resistance evolution and maintenance is needed [5], and we are far from a general understanding of how environmental factors interact and influence an organism's (absolute and relative) fitness and the effect of resistance mutations. References [1] Lenormand T, Harmand N, Gallet R. 2018. Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive concept. bioRxiv 276675, ver. 3 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/276675 | Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive concept | Thomas Lenormand, Noemie Harmand, Romain Gallet | <p>The cost of resistance, or the fitness effect of resistance mutation in absence of the drug, is a very widepsread concept in evolutionary genetics and beyond. It has represented an important addition to the simplistic view that resistance mutat... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Experimental Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Population Genetics / Genomics | Inês Fragata | 2018-03-09 02:22:07 | View | |

23 Apr 2020

How do invasion syndromes evolve? An experimental evolution approach using the ladybird Harmonia axyridisJulien Foucaud, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Virginie Ravigné, Laure Olazcuaga, Anne Loiseau, Aurelien Ausset, Su Wang, Lian-Sheng Zang, Nicolas Lemenager, Ashraf Tayeh, Arthur Weyna, Pauline Gneux, Elise Bonnet, Vincent Dreuilhe, Bastien Poutout, Arnaud Estoup, Benoit Facon https://doi.org/10.1101/849968Selection on a single trait does not recapitulate the evolution of life-history traits seen during an invasionRecommended by Inês Fragata and Ben Phillips based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersBiological invasions are natural experiments, and often show that evolution can affect dynamics in important ways [1-3]. While we often think of invasions as a conservation problem stemming from anthropogenic introductions [4,5], biological invasions are much more commonplace than this, including phenomena as diverse as natural range shifts, the spread of novel pathogens, and the growth of tumors. A major question across all these settings is which set of traits determine the ability of a population to invade new space [6,7]. Traits such as: increased growth or reproductive rate, dispersal ability and ability to defend from predation often show large evolutionary shifts across invasion history [1,6,8]. Are such multi-trait shifts driven by selection on multiple traits, or a correlated response by multiple traits to selection on one? Resolving this question is important for both theoretical and practical reasons [9,10]. But despite the importance of this issue, it is not easy to perform the necessary manipulative experiments [9]. References [1] Sakai, A.K., Allendorf, F.W., Holt, J.S. et al. (2001). The population biology of invasive species. Annual review of ecology and systematics, 32(1), 305-332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114037 | How do invasion syndromes evolve? An experimental evolution approach using the ladybird Harmonia axyridis | Julien Foucaud, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Virginie Ravigné, Laure Olazcuaga, Anne Loiseau, Aurelien Ausset, Su Wang, Lian-Sheng Zang, Nicolas Lemenager, Ashraf Tayeh, Arthur Weyna, Pauline Gneux, Elise Bonnet, Vincent Dreuilhe, Bastien Poutout, Arnaud Est... | <p>Experiments comparing native to introduced populations or distinct introduced populations to each other show that phenotypic evolution is common and often involves a suit of interacting phenotypic traits. We define such sets of traits that evol... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Experimental Evolution, Life History, Quantitative Genetics | Inês Fragata | 2019-11-29 07:07:00 | View | |

11 Oct 2021

Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansionsMaxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Vincent Calcagno, Camille Duraj, Simon Fellous, Géraldine Groussier, Eric Lombaert, Ludovic Mailleret, Anaël Marchand, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433752Phenotypic evolution during range expansions is contingent on connectivity and density dependenceRecommended by Inês Fragata based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersUnderstanding the mechanisms underlying range expansions is key for predicting species distributions in response to environmental changes (such as global warming) and managing the global expansion of invasive species (Parmesan 2006; Suarez & Tsutsui 2008). Traditionally, two types of ecological processes were studied as essential in shaping range expansion: dispersal and population growth. However, ecology and evolution are intertwined in range expansions, as phenotypic evolution of traits involved in demographic and dispersal patterns and processes can affect and be affected by ecological dynamics, representing a full eco-evolutionary loop (Williams et al. 2019; Miller et al. 2020). Range expansions can be characterized by the type of population growth and dispersal, divided into pushed or pulled range expansions. Species that have high dispersal and high population growth at low densities present pulled range expansions (pulled by individuals from the edge populations). In contrast, populations presenting increased growth rate at intermediate densities (due to Allee effects - Allee & Bowen 1932; i.e. where growth rate decreases at lower densities) and high dispersal at high densities present pushed range expansions (driven by individuals from core and intermediate populations) (Gandhi et al. 2016). Importantly, the type of expansion is expected to have very different consequences on the genetic (and therefore) phenotypic composition of core and edge populations. Specifically, genetic variability is expected to be lower in populations experiencing pulled expansions and higher in populations involved in pushed expansions (Gandhi et al. 2016; Miller et al. 2020). However, it is not always possible to distinguish between pulled and pushed expansions, as variation in speed and shape can overlap between the two types. In addition, it is difficult to experimentally manipulate the strength of the Allee effect to create pushed versus pulled expansions. Thus, several critical predictions regarding the genetic and phenotypic composition of pulled and pushed expansions are lacking empirical tests (but see Gandhi et al. 2016). In a previous study, Dahirel et al. (2021a) combined simulations and experimental evolution of the small wasps Trichogramma brassicae to show that low connectivity led to more pushed expansions, and higher connectivity generated more pulled expansions. In accordance with theoretical predictions, this led to reduced genetic diversity in pulled expansions, and the reverse pattern in pushed expansions. However, the question of how pulled and pushed expansions affect trait evolution remained unanswered. In this follow-up study, Dahirel et al. (2021b) tackled this issue and linked the changes in connectivity and type of expansion with the phenotypic evolution of several traits using individuals from their previous experiment. Namely, the authors compared core and edge populations with founder strains to test how evolution in pushed vs. pulled expansions affected wasp size, short movement, fecundity, dispersal, and density dependent dispersal. When density dependence was not accounted for, phenotypic changes in edge populations did not match the expectations from changes in expansion dynamics. This could be due to genetic trade-offs between traits that limit phenotypic evolution (Urquhart & Williams 2021). However, when accounting for density dependent dispersal, Dahirel et al. (2021b) observed that more connected landscapes (with pulled expansions) showed positive density dispersal in core populations and negative density dispersal in edge populations, similarly to other studies (e.g. Fronhofer et al. 2017). Interestingly, in pushed (with lower connectivity) landscapes, such shift was not observed. Instead, edge populations maintained positive density dispersal even after 14 generations of expansion, whereas core populations showed higher dispersal at lower density. The authors suggest that this seemingly contradictory result is due to a combination of three processes: 1) the expansion reduced positive density dispersal in edge populations; 2) reduced connectivity directly increased dispersal costs, increasing high density dispersal; and 3) reduced connectivity indirectly caused demographic stochasticity (and reduced temporal variability in patches) leading to higher dispersal at low density in core populations. However, these results must be taken with a grain of salt, since only one of the four experimental replicates were used in the density dependent dispersal experiment. In range expansions experiments, replication is fundamental, since stochastic processes (such as gene surfing, where alleles maybe rise in frequency due by chance) are prevalent (Miller et al. 2020), and results are highly dependent on sample size, or number of replicate populations analysed. Having said that, results from Dahirel et al. (2021b) highlight the importance to contextualize the management of invasions and species distribution, since it is thought that pulled expansions are more prevalent in nature, but pushed expansions can be more important in scenarios where patchiness is high, such as urban landscapes. Moreover, Dahirel's et al. (2021b) study is a first step showing that accounting for trait density dependence is crucial when following phenotypic evolution during range expansion, and that evolution of density dependent traits may be constrained by landscape conditions. This highlights the need to account for both connectivity and density dependence to draw more accurate predictions on the evolutionary and ecological outcomes of range expansions. Allee WC, Bowen ES (1932) Studies in animal aggregations: Mass protection against colloidal silver among goldfishes. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 61, 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.1400610202 Dahirel M, Bertin A, Calcagno V, Duraj C, Fellous S, Groussier G, Lombaert E, Mailleret L, Marchand A, Vercken E (2021a) Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansions. bioRxiv, 2021.03.03.433752, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433752 Dahirel M, Bertin A, Haond M, Blin A, Lombaert E, Calcagno V, Fellous S, Mailleret L, Malausa T, Vercken E (2021b) Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivity. Oikos, 130, 708–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.08278 Fronhofer EA, Gut S, Altermatt F (2017) Evolution of density-dependent movement during experimental range expansions. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 30, 2165–2176. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13182 Gandhi SR, Yurtsev EA, Korolev KS, Gore J (2016) Range expansions transition from pulled to pushed waves as growth becomes more cooperative in an experimental microbial population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 6922–6927. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1521056113 Miller TEX, Angert AL, Brown CD, Lee-Yaw JA, Lewis M, Lutscher F, Marculis NG, Melbourne BA, Shaw AK, Szűcs M, Tabares O, Usui T, Weiss-Lehman C, Williams JL (2020) Eco-evolutionary dynamics of range expansion. Ecology, 101, e03139. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3139 Parmesan C (2006) Ecological and Evolutionary Responses to Recent Climate Change. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 37, 637–669. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110100 Suarez AV, Tsutsui ND (2008) The evolutionary consequences of biological invasions. Molecular Ecology, 17, 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03456.x Urquhart CA, Williams JL (2021) Trait correlations and landscape fragmentation jointly alter expansion speed via evolution at the leading edge in simulated range expansions. Theoretical Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-021-00503-z Williams JL, Hufbauer RA, Miller TEX (2019) How Evolution Modifies the Variability of Range Expansion. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34, 903–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.05.012 | Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansions | Maxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Vincent Calcagno, Camille Duraj, Simon Fellous, Géraldine Groussier, Eric Lombaert, Ludovic Mailleret, Anaël Marchand, Elodie Vercken | <p style="text-align: justify;">As human influence reshapes communities worldwide, many species expand or shift their ranges as a result, with extensive consequences across levels of biological organization. Range expansions can be ranked on a con... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution | Inês Fragata | 2021-03-05 17:15:46 | View | |

24 Oct 2022

Evolutionary responses of energy metabolism, development, and reproduction to artificial selection for increasing heat tolerance in Drosophila subobscuraAndres Mesas, Luis E. Castaneda https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.03.479001The other side of the evolution of heat tolerance: correlated responses in metabolism and life-history traitsRecommended by Inês Fragata and Pedro Simões based on reviews by Marija Savić Veselinović and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Marija Savić Veselinović and 1 anonymous reviewer

Understanding how species respond to environmental changes is becoming increasingly important in order to predict the future of biodiversity and species distributions under current global warming conditions (Rezende 2020; Bennett et al 2021). Two key factors to take into account in these predictions are the tolerance of organisms to heat stress and subsequently how they adapt to increasingly warmer temperatures. Coupled with this, one important factor that is often overlooked when addressing the evolution of thermal tolerance, is the correlated responses in traits that are important to fitness, such as life histories, behavior and the underlying metabolic processes. The rate and intensity of the thermal stress are expected to be major factors in shaping the evolution of heat tolerance and correlated responses in other traits. For instance, lower rates of thermal stress are predicted to select for individuals with a slower metabolism (Santos et al 2012), whereas low metabolism is expected to lead to a lower reproductive rate (Dammhahn et al 2018). To quantify the importance of the rate and intensity of thermal stress on the evolutionary response of heat tolerance and correlated response in behavior, Mesas et al (2021) performed experimental evolution in Drosophila subobscura using selective regimes with slow or fast ramping protocols. Whereas both regimes showed increased heat tolerance with similar evolutionary rates, the correlated responses in thermal performance curves for locomotor behavior differed between selection regimes. These findings suggest that thermal rate and intensity may shape the evolution of correlated responses in other traits, urging the need to understand possible correlated responses at relevant levels such as life history and metabolism. In the present contribution, Mesas and Castañeda (2022) investigate whether the disparity in thermal performance curves observed in the previous experiment (Mesas et al 2021) could be explained by differences in metabolic energy production and consumption, and how this correlated with the reproductive output (fecundity and viability). Overall, the authors show some evidence for lowered enzyme activity and increased performance in life-history traits, particularly for the slow-ramping selected flies. Specifically, the authors observe a reduction in glucose metabolism and increased viability when evolving under slow ramping stress. Interestingly, both regimes show a general increase in fecundity, suggesting that adaptation to these higher temperatures is not costly (for reproduction) in the ancestral environment. The evidence for a somewhat lower metabolism in the slow-ramping lines suggests the evolution of a slow “pace of life”. The “pace of life” concept tries to bridge variation across several levels namely metabolism, physiology, behavior and life history, with low “pace of life” organisms presenting lower metabolic rates, later reproduction and higher longevity than fast “pace of life” organisms (Dammhahn et al 2018, Tuzun & Stocks 2022). As the authors state there is not a clear-cut association with the expectations of the pace of life hypothesis since there was evidence for increased reproductive output under both selection intensity regimes. This suggests that, given sufficient trait genetic variance, positively correlated responses may emerge during some stages of thermal evolution. As fecundity estimates in this study were focussed on early life, the possibility of a decrease in the cumulative reproductive output of the selected flies, even under benign conditions, cannot be excluded. This would help explain the apparent paradox of increased fecundity in selected lines. In this context, it would also be interesting to explore the variation in reproductive output at different temperatures, i.e to obtain thermal performance curves for life histories. Mesas and Castañeda (2022) raise important questions to pursue in the future and contribute to the growing evidence that, in order to predict the distribution of ectothermic species under current global warming conditions, we need to expand beyond determining the physiological thermal limits of each organism (Parratt et al 2021). Ultimately, integrating metabolic, life-history and behavioral changes during evolution under different thermal stresses within a coherent framework is key to developing better predictions of temperature effects on natural populations. Bennett, J.M., Sunday, J., Calosi, P. et al. The evolution of critical thermal limits of life on Earth. Nat Commun 12, 1198 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21263-8 Dammhahn, M., Dingemanse, N.J., Niemelä, P.T. et al. Pace-of-life syndromes: a framework for the adaptive integration of behaviour, physiology and life history. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 72, 62 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2473-y Mesas, A, Jaramillo, A, Castañeda, LE. Experimental evolution on heat tolerance and thermal performance curves under contrasting thermal selection in Drosophila subobscura. J Evol Biol 34, 767– 778 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13777 Parratt, S.R., Walsh, B.S., Metelmann, S. et al. Temperatures that sterilize males better match global species distributions than lethal temperatures. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 481–484 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01047-0 Santos, M, Castañeda, LE, Rezende, EL Keeping pace with climate change: what is wrong with the evolutionary potential of upper thermal limits? Ecology and evolution, 2(11), 2866-2880 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.385 Tüzün, N, Stoks, R. A fast pace-of-life is traded off against a high thermal performance. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289(1972), 20212414 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.2414 Rezende, EL, Bozinovic, F, Szilágyi, A, Santos, M. Predicting temperature mortality and selection in natural Drosophila populations. Science, 369(6508), 1242-1245 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba9287 | Evolutionary responses of energy metabolism, development, and reproduction to artificial selection for increasing heat tolerance in Drosophila subobscura | Andres Mesas, Luis E. Castaneda | <p>Adaptations to warming conditions exhibited by ectotherms include increasing heat tolerance but also metabolic changes to reduce maintenance costs (metabolic depression), which can allow them to redistribute the energy surplus to biological fun... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Life History | Inês Fragata | 2022-02-08 01:05:50 | View | |

22 Feb 2023

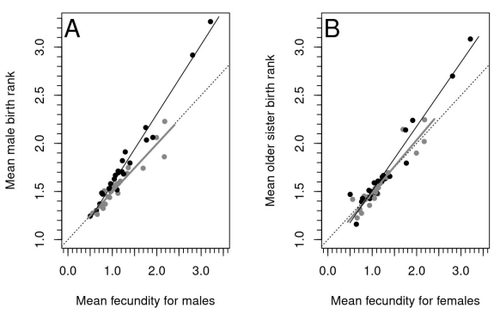

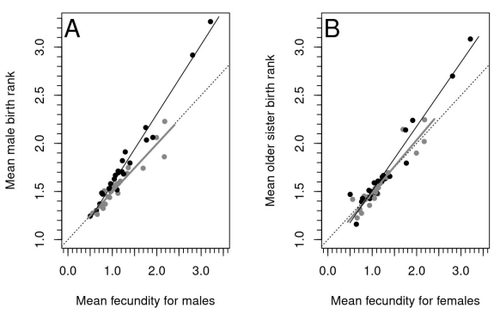

Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesisMichel Raymond, Daniel Turek, Valerie Durand, Sarah Nila, Bambang Suryobroto, Julien Vadez, Julien Barthes, Menelaos Apostolou, Pierre-André Crochet https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.22.481477Evolutionary or proximal explanations for human male homosexual mate preference?Recommended by Jacqui A. Shykoff based on reviews by Ray Blanchard and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Ray Blanchard and 1 anonymous reviewer

Natural populations do not consist of only perfectly adapted individuals. If they did, of course, there would be no fodder for evolution by natural selection. And natural selection is operating all the time, winnowing out less well adapted phenotypes through differential reproduction and survival. Demonstrations of natural selection modifying characters-state distributions to bring phenotypes closer to their optima abound in the evolution literature, with examples of short- and long-term changes in phenotype and allele frequencies. However, evolutionary biologists know that populations cannot reach their adaptive peaks. Natural selection is tracking a moving target, always with some generations of lag time. The adaptive landscape is multidimensional, so the optimal combination of multiple character states may be impossible because of constraints and trade-offs. Natural selection does not operate alone or in isolation – new mutations and migrants that were selected under other conditions will inject locally non-adaptive genetic variation and genetic drift can change allele frequencies in random directions. We understand these processes that generate and maintain less advantageous variants on a continuous gradient from an optimal phenotype in a fitness landscape. More puzzling are heritable polymorphisms with distinct morphologies, physiologies or behaviours maintained in populations despite their measurably lower reproductive success. But a complete model of evolution must also be able to accommodate these Darwinian paradoxes. Raymond et al. (2023) investigate one such Darwinian paradox: In humans, male homosexual mate preference is heritable and is associated with a large reduction in offspring production but nonetheless occurs at relatively high frequencies in most human populations. Furthermore, multiple studies have found that homosexual men come from families that are, on average, larger than those of heterosexual men and that homosexual men have, on average, higher birth rank than do heterosexual men, i.e., having more older siblings and, particularly, more older brothers. Two types of mechanisms consistent with these observations have been proposed: 1) An evolutionary mechanism of sex-antagonistic pleiotropy, whereby highly fecund mothers are more likely to produce homosexual sons, and 2) A mechanistic explanation whereby successive male pregnancies alter the uterine environment by increasing the probability of an immune reaction by the mother to her male fetus, altering development of sexually dimorphic brain structures relevant to sexual orientation. In this article, the authors explore these two mechanisms of sex-antagonistic effects (AE) and fraternal birth order effects (FBOE) and test how well they account for patterns of male homosexuality in population and family data. Clearly, these two effects are somewhat confounded because high birth ranks can only occur in large families. If, indeed, the probability of male homosexuality increases with increasing numbers of (maternal) older brothers, homosexual males will be more common in larger families. Similarly, if high female fecundity leads to a higher probability of male homosexuality via sex-antagonistic effects, homosexual males will, on average, have more older brothers. To disentangle the actions of these two effects the authors modelled the relationship between birth rank and population fecundity and investigated whether AE or FBOE modified this relationship for homosexual men. Simulation results were compared with aggregated population data from 13 countries. Family data on individuals’ sexual preference, birth rank and number of male and female siblings from France, Greece and Indonesia were analysed with generalised linear models and Bayesian approaches to test for a signal of AE or FBOE. These analyses revealed a significant older-brother effect (FBOE) explaining patterns of occurrence of homosexuality in population and family data but no significant independent sex-antagonistic effect (AE). Thus larger family sizes of homosexual men appear due to the older-brother effect, with individuals of high birth rank coming necessarily from large sibships. The simulation approach also revealed that modelling a fraternal birth order effect (FBOE), such that individuals with more older brothers are more likely to be homosexual, generates an artefactual older sister effect simply because homosexual men are overrepresented at higher birth ranks. Older-sister effects reported in the literature may, therefore, be statistical artefacts of an underlying older-brother effect. This paper is interesting for a number of reasons. It does an excellent job of explaining, identifying and dealing with estimation biases and testing for artefactual relationships generated by collinearity. It applies state-of-the art analytical/statistical tools. It breaks down two colinear effects and shows that only one really explains phenotypic variation. This is a great example of how to disentangle correlated variables that may or may not both contribute to trait variation. But most intriguingly, we are left without evidence for an evolutionary mechanism that compensates the large fitness cost associated with male homosexuality in humans. How can we explain high heritability maintained in the face of strong directional selection that should erode heritable genetic variation? The usual suspects include cryptic compensatory mechanisms yet to be discovered or flawed estimates of selection or heritability. For example, data on heritability of male homosexual mate preference in humans come from twin studies and twins share birth rank as well as alleles. Thus it is possible that heritability is over-estimated, including the environmental component associated with birth rank. If, as the authors demonstrate here, birth rank is the strongest predictor of male homosexual mate preference, selection may be acting on a non-heritable plastic component of phenotypic variation. This could explain why heritable variation is not exhausted by selection, rendering the paradox less paradoxical, but fails to provide an adaptive explanation for the maintenance of male homosexual mate preference. References Raymond M., Turek D., Durand V., Nila S., Suryobroto B., Vadez J., Barthes J., Apostolou M. and Crochet P.-A. (2023) Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesis. bioRxiv, 2022.02.22.481477, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.22.481477 | Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesis | Michel Raymond, Daniel Turek, Valerie Durand, Sarah Nila, Bambang Suryobroto, Julien Vadez, Julien Barthes, Menelaos Apostolou, Pierre-André Crochet | <p style="text-align: justify;">Male homosexual orientation remains a Darwinian paradox, as there is no consensus on its evolutionary (ultimate) determinants. One intriguing feature of homosexual men is their higher male birth rank compared to het... |  | Life History, Other, Phenotypic Plasticity, Reproduction and Sex | Jacqui A. Shykoff | 2022-03-03 11:28:44 | View | |

23 Nov 2020

Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mitesMiguel A. Cruz, Sara Magalhães, Élio Sucena, Flore Zélé https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.29.178699Speciation in spider mites: disentangling the roles of Wolbachia-induced vs. nuclear mating incompatibilitiesRecommended by Jan Engelstaedter based on reviews by Wolfgang Miller and 1 anonymous reviewerCytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) is a mating incompatibility that is induced by maternally inherited endosymbionts in many arthropods. These endosymbionts include, most famously, the alpha-proteobacterium Wolbachia pipientis (Yen & Barr 1971; Werren et al. 2008) but also the Bacteroidetes bacterium Cardinium hertigii (Zchori-Fein et al. 2001), a gamma-proteobacterium of the genus Rickettsiella (Rosenwald et al. 2020) and another, as yet undescribed alpha-proteobacterium (Takano et al. 2017). CI manifests as embryonic mortality in crosses between infected males and females that are uninfected or infected with a different strain, whereas embryos develop normally in all other crosses. This phenotype may enable the endosymbionts to spread rapidly within their host population. Exploiting this, CI-inducing Wolbachia are being harnessed to control insect-borne diseases (e.g., O'Neill 2018). Much progress elucidating the genetic basis and developmental mechanism of CI has been made in recent years, but many open questions remain (Shropshire et al. 2020). References Bordenstein, S. R., O'Hara, F. P., and Werren, J. H. (2001). Wolbachia-induced incompatibility precedes other hybrid incompatibilities in Nasonia. Nature, 409(6821), 707-710. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/35055543 | Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mites | Miguel A. Cruz, Sara Magalhães, Élio Sucena, Flore Zélé | <p>Wolbachia are widespread maternally-inherited bacteria suggested to play a role in arthropod host speciation through induction of cytoplasmic incompatibility, but this hypothesis remains controversial. Most studies addressing Wolbachia-induced ... | Evolutionary Ecology, Hybridization / Introgression, Life History, Reproduction and Sex, Speciation, Species interactions | Jan Engelstaedter | 2020-07-09 10:18:28 | View | ||

10 Jan 2019

Genomic data provides new insights on the demographic history and the extent of recent material transfers in Norway spruceJun Chen, Lili Li, Pascal Milesi, Gunnar Jansson, Mats Berlin, Bo Karlsson, Jelena Aleksic, Giovanni G Vendramin, Martin Lascoux https://doi.org/10.1101/402016Disentangling the recent and ancient demographic history of European spruce speciesRecommended by Jason Holliday based on reviews by 1 anonymous reviewerGenetic diversity in temperate and boreal forests tree species has been strongly affected by late Pleistocene climate oscillations [2,3,5], but also by anthropogenic forces. Particularly in Europe, where a long history of human intervention has re-distributed species and populations, it can be difficult to know if a given forest arose through natural regeneration and gene flow or through some combination of natural and human-mediated processes. This uncertainty can confound inferences of the causes and consequences of standing genetic variation, which may impact our interpretation of demographic events that shaped species before humans became dominant on the landscape. In their paper entitled "Genomic data provides new insights on the demographic history and the extent of recent material transfers in Norway spruce", Chen et al. [1] used a genome-wide dataset of 400k SNPs to infer the demographic history of Picea abies (Norway spruce), the most widespread and abundant spruce species in Europe, and to understand its evolutionary relationship with two other spruces (Picea obovata [Siberian spruce] and P. omorika [Serbian spruce]). Three major Norway spruce clusters were identified, corresponding to central Europe, Russia and the Baltics, and Scandinavia, which agrees with previous studies. The density of the SNP data in the present paper enabled inference of previously uncharacterized admixture between these groups, which corresponds to the timing of postglacial recolonization following the last glacial maximum (LGM). This suggests that multiple migration routes gave rise to the extant distribution of the species, and may explain why Chen et al.'s estimates of divergence times among these major Norway spruce groups were older (15mya) than those of previous studies (5-6mya) – those previous studies may have unknowingly included admixed material [4]. Treemix analysis also revealed extensive admixture between Norway and Siberian spruce over the last ~100k years, while the geographically-restricted Serbian spruce was both isolated from introgression and had a dramatically smaller effective population size (Ne) than either of the other two species. This small Ne resulted from a bottleneck associated with the onset of the iron age ~3000 years ago, which suggests that anthropogenic depletion of forest resources has severely impacted this species. Finally, ancestry of Norway spruce samples collected in Sweden and Denmark suggest their recent transfer from more southern areas of the species range. This northward movement of genotypes likely occurred because the trees performed well relative to local provenances, which is a common observation when trees from the south are planted in more northern locations (although at the potential cost of frost damage due to inappropriate phenology). While not the reason for the transfer, the incorporation of southern seed sources into the Swedish breeding and reforestation program may lead to more resilient forests under climate change. Taken together, the data and analysis presented in this paper allowed inference of the intra- and interspecific demographic histories of a tree species group at a very high resolution, and suggest caveats regarding sampling and interpretation of data from areas with a long history of occupancy by humans. References [1] Chen, J., Milesi, P., Jansson, G., Berlin, M., Karlsson, B., Aleksić, J. M., Vendramin, G. G., Lascoux, M. (2018). Genomic data provides new insights on the demographic history and the extent of recent material transfers in Norway spruce. BioRxiv, 402016. ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/402016 | Genomic data provides new insights on the demographic history and the extent of recent material transfers in Norway spruce | Jun Chen, Lili Li, Pascal Milesi, Gunnar Jansson, Mats Berlin, Bo Karlsson, Jelena Aleksic, Giovanni G Vendramin, Martin Lascoux | <p>Primeval forests are today exceedingly rare in Europe and transfer of forest reproductive material for afforestation and improvement have been very common, especially over the last two centuries. This can be a serious impediment when inferring ... | Evolutionary Applications, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics | Jason Holliday | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2018-08-29 08:33:15 | View | |

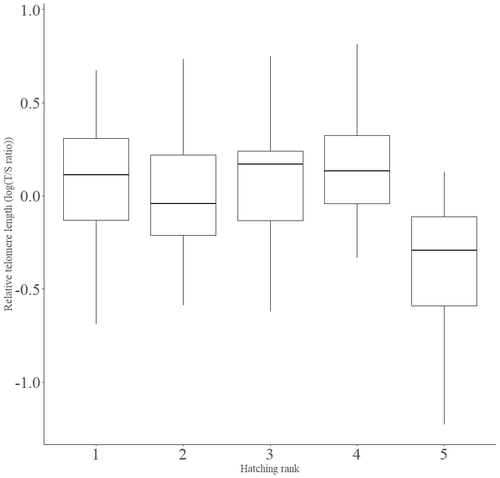

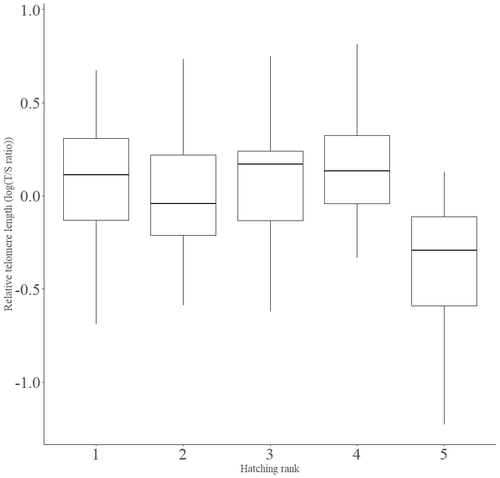

30 Oct 2023

Telomere length vary with sex, hatching rank and year of birth in little owls, Athene noctuaFrançois Criscuolo, Inès Fache, Bertrand Scaar, Sandrine Zahn, Josefa Bleu https://doi.org/10.32942/X2BS3SDeciphering the relative contribution of environmental and biological factors driving telomere length in nestlingsRecommended by Jean-François Lemaitre based on reviews by Florentin Remot and 1 anonymous reviewerThe search for physiological markers of health and survival in wild animal populations is attracting a great deal of interest. At present, there is no (and may never be) consensus on such a single, robust marker but of all the proposed physiological markers, telomere length is undoubtedly the most widely studied in the field of evolutionary ecology (Monaghan et al., 2022). Broadly speaking, telomeres are non-coding DNA sequences located at the end of chromosomes in eukaryotes, protecting genomic DNA against oxidative stress and various detrimental processes (e.g. DNA end-joining) and thus maintaining genome stability (Blackburn et al., 2015). However, in most somatic cells from the vast majority of the species, telomere sequences are not replicated and telomere length progressively declines with increased age (Remot et al., 2022). This shortening of telomere length upon a critical level is causally linked to cellular senescence and has been invoked as one of the primary causes of the aging process (López-Otín et al., 2023). Studies performed in both captive and wild populations of animals have further demonstrated that short telomeres (or telomere sequences with a fast attrition rate) are to some extent associated with an increased risk of mortality, even if the magnitude of this association largely differs between species and populations (Wilbourn et al., 2018). The repeated observations of associations between telomere length and mortality risk have called for studies seeking to identify the ecological and biological factors that – beyond chronological age – shape the between-individual variability in telomere length. A wide spectrum of environmental stressors such as the level of exposure to pathogens or the degree of human disturbances has been proposed as possible modulators of telomere dynamics (see Chatelain et al., 2019). However, within species, the relative contribution of various ecological and biological factors on telomere length has been rarely quantified. In that context, the study of Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) constitutes a timely attempt to decipher the relative contribution of environmental and biological factors driving telomere length in nestlings (i.e. when individuals are between 15 and 35 days of age) from a wild population of little owls, Athene noctua. In addition to chronological age, Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) analysed the effects of two environmental variables (i.e. cohort and habitat quality) as well as three life history traits (i.e. hatching rank, sex and body condition). Among these traits, sex was found to impact nestling’s telomere length with females carrying longer telomeres than males. Traditionally, the among-individuals variability in telomere length during the juvenile period is interpreted as a direct consequence of differences in growth allocation. Fast-growing individuals are typically supposed to undergo more cell divisions and a higher exposure to oxidative stress, which ultimately shortens telomeres (Monaghan & Ozanne, 2018). Whether - despite a slightly female-biased sexual size dimorphism - male little owls display a condensed period of fast growth that could explain their shorter telomere is yet to be determined. Future studies should also explore the consequences of these sex differences in telomere length in terms of mortality risk. In birds, it has been observed that telomere length during early life can predict lifespan (see Heidinger et al., 2012 in zebra finches, Taeniopygia guttata), suggesting that females little owls might live longer than their conspecific males. Yet, adult mortality is generally female-biased in birds (Liker & Székely, 2005) and whether little owls constitute an exception to this rule - possibly mediated by sex-specific telomere dynamics - remains to be explored. Quite surprisingly, the present study in little owls did not evidence any clear effect of environmental conditions on nestling’s telomere length, at both temporal and special scales. While a trend for a temporal effect was detected with telomere length being slightly shorter for nestling born the last year of the study (out of 4 years analysed), habitat quality (measured by the proportion of meadow and orchards in the nest environment) had absolutely no impact on nestling telomere length. Recently published studies in wild populations of vertebrates have highlighted the detrimental effects of harsh environmental conditions on telomere length (e.g. Dupoué et al., 2022 in common lizards, Zootoca vivipara), arguing for a key role of telomere dynamics in the emerging field of conservation physiology. While we can recognize the relevance of such an integrative approach, especially in the current context of climate change, the study by Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) reminds us that the relationships between environmental conditions and telomere dynamics are far from straightforward. Depending on the species and its life history, telomere length in early life could indeed capture very different environmental signals. References Blackburn, E. H., Epel, E. S., & Lin, J. (2015). Human telomere biology: A contributory and interactive factor in aging, disease risks, and protection. Science, 350(6265), 1193-1198. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab3389 | Telomere length vary with sex, hatching rank and year of birth in little owls, *Athene noctua* | François Criscuolo, Inès Fache, Bertrand Scaar, Sandrine Zahn, Josefa Bleu | <p>Telomeres are non-coding DNA sequences located at the end of linear chromosomes, protecting genome integrity. In numerous taxa, telomeres shorten with age and telomere length (TL) is positively correlated with longevity. Moreover, TL is also af... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Jean-François Lemaitre | 2023-03-07 09:44:32 | View | |

01 Mar 2021

Social Conflicts in Dictyostelium discoideum : A Matter of ScalesForget, Mathieu; Adiba, Sandrine; De Monte, Silvia https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03088868/The cell-level perspective in social conflicts in Dictyostelium discoideumRecommended by Jeremy Van Cleve based on reviews by Peter Conlin and ?The social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum is an important model system for the study of cooperation and multicellularity as is has both unicellular and aggregative life phases. In the aggregative phase, which typically occurs when nutrients are limiting, individual cells eventually gather together to form a fruiting bodies whose spores may be dispersed to another, better, location and whose stalk cells, which support the spores, die. This extreme form of cooperation has been the focus of numerous studies that have revealed the importance genetic relatedness and kin selection (Hamilton 1964; Lehmann and Rousset 2014) in explaining the maintenance of this cooperative collective behavior (Strassmann et al. 2000; Kuzdzal-Fick et al. 2011; Strassmann and Queller 2011). However, much remains unknown with respect to how the interactions between individual cells, their neighbors, and their environment produce cooperative behavior at the scale of whole groups or collectives. In this preprint, Forget et al. (2021) describe how the D. discoideum system is crucial in this respect because it allows these cellular-level interactions to be studied in a systematic and tractable manner. References Forget, M., Adiba, S. and De Monte, S.(2021) Social conflicts in *Dictyostelium discoideum *: a matter of scales. HAL, hal-03088868, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03088868/ Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour. II. Journal of theoretical biology, 7(1), 17-52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(64)90039-6 Kuzdzal-Fick, J. J., Fox, S. A., Strassmann, J. E., and Queller, D. C. (2011). High relatedness is necessary and sufficient to maintain multicellularity in Dictyostelium. Science, 334(6062), 1548-1551. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1213272 Lehmann, L., and Rousset, F. (2014). The genetical theory of social behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1642), 20130357. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0357 Strassmann, J. E., and Queller, D. C. (2011). Evolution of cooperation and control of cheating in a social microbe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(Supplement 2), 10855-10862. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1102451108 Strassmann, J. E., Zhu, Y., & Queller, D. C. (2000). Altruism and social cheating in the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature, 408(6815), 965-967. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/35050087 Thompson, C. R., & Kay, R. R. (2000). Cell-fate choice in Dictyostelium: intrinsic biases modulate sensitivity to DIF signaling. Developmental biology, 227(1), 56-64. doi: https://doi.org/10.1006/dbio.2000.9877 | Social Conflicts in Dictyostelium discoideum : A Matter of Scales | Forget, Mathieu; Adiba, Sandrine; De Monte, Silvia | <p>The 'social amoeba' Dictyostelium discoideum, where aggregation of genetically heterogeneous cells produces functional collective structures, epitomizes social conflicts associated with multicellular organization. 'Cheater' populations that hav... | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Experimental Evolution | Jeremy Van Cleve | 2020-08-28 10:37:21 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer