Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

12 Jun 2017

Modelling the evolution of how vector-borne parasites manipulate the vector's host choiceRecommended by Samuel Alizon based on reviews by Samuel Alizon and Nicole Mideo based on reviews by Samuel Alizon and Nicole Mideo

Many parasites can manipulate their hosts, thus increasing their transmission to new hosts [1]. This is particularly the case for vector-borne parasites, which can alter the feeding behaviour of their hosts. However, predicting the optimal strategy is not straightforward because three actors are involved and the interests of the parasite may conflict with that of the vector. There are few models that consider the evolution of host manipulation by parasites [but see 2-4], but there are virtually none that investigated how parasites can manipulate the host choice of vectors. Even on the empirical side, many aspects of this choice remain unknown. Gandon [5] develops a simple evolutionary epidemiology model that allows him to formulate clear and testable predictions. These depend on which actor controls the trait (the vector or the parasite) and, when there is manipulation, whether it is realised via infected hosts (to attract vectors) or infected vectors (to change host choice). In addition to clarifying the big picture, Gandon [5] identifies some nice properties of the model, for instance an independence of the density/frequency-dependent transmission assumption or a backward bifurcation at R0=1, which suggests that parasites could persist even if their R0 is driven below unity. Overall, this study calls for further investigation of the different scenarios with more detailed models and experimental validation of general predictions. References [1] Hughes D, Brodeur J, Thomas F. 2012. Host manipulation by parasites. Oxford University Press. [2] Brown SP. 1999. Cooperation and conflict in host-manipulating parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 266: 1899–1904. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0864 [3] Lion S, van Baalen M, Wilson WG. 2006. The evolution of parasite manipulation of host dispersal. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 273: 1063–1071. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3412 [4] Vickery WL, Poulin R. 2010. The evolution of host manipulation by parasites: a game theory analysis. Evolutionary Ecology 24: 773–788. doi: 10.1007/s10682-009-9334-0 [5] Gandon S. 2017. Evolution and manipulation of vector host choice. bioRxiv 110577, ver. 3 of 7th June 2017. doi: 10.1101/110577 | Evolution and manipulation of vector host choice | Sylvain Gandon | The transmission of many animal and plant diseases relies on the behavior of arthropod vectors. In particular, the choice to feed on either infected or uninfected hosts can dramatically affect the epidemiology of vector-borne diseases. I develop a... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Samuel Alizon | 2017-03-03 19:18:54 | View | |

06 Jun 2019

Multi-model inference of non-random mating from an information theoretic approachAntonio Carvajal-Rodríguez https://doi.org/10.1101/305730Tell me who you mate with, I’ll tell you what’s going onRecommended by Sara Magalhaes and Alexandre Courtiol based on reviews by Alexandre Courtiol and 2 anonymous reviewersThe study of sexual selection goes as far as Darwin himself. Since then, elaborate theories concerning both intra- and inter-sexual sexual have been developed, and elegant experiments have been designed to test this body of theory. It may thus come as a surprise that the community is still debating on the correct way to measure simple components of sexual selection, such as the Bateman gradient (i.e., the covariance between the number of matings and the number of offspring)[1,2], or to quantify complex behaviours such as mate choice (the non-random choice of individuals with particular characters as mates)[3,4] and their consequences. References [1] Bateman, A. J. (1948). Intra-sexual selection in Drosophila. Heredity, 2(3), 349-368. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1948.21 | Multi-model inference of non-random mating from an information theoretic approach | Antonio Carvajal-Rodríguez | <p>Non-random mating has a significant impact on the evolution of organisms. Here, I developed a modelling framework for discrete traits (with any number of phenotypes) to explore different models connecting the non-random mating causes (mate comp... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Sexual Selection | Sara Magalhaes | 2019-02-08 19:24:03 | View | |

11 Oct 2021

Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansionsMaxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Vincent Calcagno, Camille Duraj, Simon Fellous, Géraldine Groussier, Eric Lombaert, Ludovic Mailleret, Anaël Marchand, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433752Phenotypic evolution during range expansions is contingent on connectivity and density dependenceRecommended by Inês Fragata based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersUnderstanding the mechanisms underlying range expansions is key for predicting species distributions in response to environmental changes (such as global warming) and managing the global expansion of invasive species (Parmesan 2006; Suarez & Tsutsui 2008). Traditionally, two types of ecological processes were studied as essential in shaping range expansion: dispersal and population growth. However, ecology and evolution are intertwined in range expansions, as phenotypic evolution of traits involved in demographic and dispersal patterns and processes can affect and be affected by ecological dynamics, representing a full eco-evolutionary loop (Williams et al. 2019; Miller et al. 2020). Range expansions can be characterized by the type of population growth and dispersal, divided into pushed or pulled range expansions. Species that have high dispersal and high population growth at low densities present pulled range expansions (pulled by individuals from the edge populations). In contrast, populations presenting increased growth rate at intermediate densities (due to Allee effects - Allee & Bowen 1932; i.e. where growth rate decreases at lower densities) and high dispersal at high densities present pushed range expansions (driven by individuals from core and intermediate populations) (Gandhi et al. 2016). Importantly, the type of expansion is expected to have very different consequences on the genetic (and therefore) phenotypic composition of core and edge populations. Specifically, genetic variability is expected to be lower in populations experiencing pulled expansions and higher in populations involved in pushed expansions (Gandhi et al. 2016; Miller et al. 2020). However, it is not always possible to distinguish between pulled and pushed expansions, as variation in speed and shape can overlap between the two types. In addition, it is difficult to experimentally manipulate the strength of the Allee effect to create pushed versus pulled expansions. Thus, several critical predictions regarding the genetic and phenotypic composition of pulled and pushed expansions are lacking empirical tests (but see Gandhi et al. 2016). In a previous study, Dahirel et al. (2021a) combined simulations and experimental evolution of the small wasps Trichogramma brassicae to show that low connectivity led to more pushed expansions, and higher connectivity generated more pulled expansions. In accordance with theoretical predictions, this led to reduced genetic diversity in pulled expansions, and the reverse pattern in pushed expansions. However, the question of how pulled and pushed expansions affect trait evolution remained unanswered. In this follow-up study, Dahirel et al. (2021b) tackled this issue and linked the changes in connectivity and type of expansion with the phenotypic evolution of several traits using individuals from their previous experiment. Namely, the authors compared core and edge populations with founder strains to test how evolution in pushed vs. pulled expansions affected wasp size, short movement, fecundity, dispersal, and density dependent dispersal. When density dependence was not accounted for, phenotypic changes in edge populations did not match the expectations from changes in expansion dynamics. This could be due to genetic trade-offs between traits that limit phenotypic evolution (Urquhart & Williams 2021). However, when accounting for density dependent dispersal, Dahirel et al. (2021b) observed that more connected landscapes (with pulled expansions) showed positive density dispersal in core populations and negative density dispersal in edge populations, similarly to other studies (e.g. Fronhofer et al. 2017). Interestingly, in pushed (with lower connectivity) landscapes, such shift was not observed. Instead, edge populations maintained positive density dispersal even after 14 generations of expansion, whereas core populations showed higher dispersal at lower density. The authors suggest that this seemingly contradictory result is due to a combination of three processes: 1) the expansion reduced positive density dispersal in edge populations; 2) reduced connectivity directly increased dispersal costs, increasing high density dispersal; and 3) reduced connectivity indirectly caused demographic stochasticity (and reduced temporal variability in patches) leading to higher dispersal at low density in core populations. However, these results must be taken with a grain of salt, since only one of the four experimental replicates were used in the density dependent dispersal experiment. In range expansions experiments, replication is fundamental, since stochastic processes (such as gene surfing, where alleles maybe rise in frequency due by chance) are prevalent (Miller et al. 2020), and results are highly dependent on sample size, or number of replicate populations analysed. Having said that, results from Dahirel et al. (2021b) highlight the importance to contextualize the management of invasions and species distribution, since it is thought that pulled expansions are more prevalent in nature, but pushed expansions can be more important in scenarios where patchiness is high, such as urban landscapes. Moreover, Dahirel's et al. (2021b) study is a first step showing that accounting for trait density dependence is crucial when following phenotypic evolution during range expansion, and that evolution of density dependent traits may be constrained by landscape conditions. This highlights the need to account for both connectivity and density dependence to draw more accurate predictions on the evolutionary and ecological outcomes of range expansions. Allee WC, Bowen ES (1932) Studies in animal aggregations: Mass protection against colloidal silver among goldfishes. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 61, 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.1400610202 Dahirel M, Bertin A, Calcagno V, Duraj C, Fellous S, Groussier G, Lombaert E, Mailleret L, Marchand A, Vercken E (2021a) Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansions. bioRxiv, 2021.03.03.433752, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433752 Dahirel M, Bertin A, Haond M, Blin A, Lombaert E, Calcagno V, Fellous S, Mailleret L, Malausa T, Vercken E (2021b) Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivity. Oikos, 130, 708–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.08278 Fronhofer EA, Gut S, Altermatt F (2017) Evolution of density-dependent movement during experimental range expansions. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 30, 2165–2176. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13182 Gandhi SR, Yurtsev EA, Korolev KS, Gore J (2016) Range expansions transition from pulled to pushed waves as growth becomes more cooperative in an experimental microbial population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 6922–6927. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1521056113 Miller TEX, Angert AL, Brown CD, Lee-Yaw JA, Lewis M, Lutscher F, Marculis NG, Melbourne BA, Shaw AK, Szűcs M, Tabares O, Usui T, Weiss-Lehman C, Williams JL (2020) Eco-evolutionary dynamics of range expansion. Ecology, 101, e03139. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3139 Parmesan C (2006) Ecological and Evolutionary Responses to Recent Climate Change. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 37, 637–669. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110100 Suarez AV, Tsutsui ND (2008) The evolutionary consequences of biological invasions. Molecular Ecology, 17, 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03456.x Urquhart CA, Williams JL (2021) Trait correlations and landscape fragmentation jointly alter expansion speed via evolution at the leading edge in simulated range expansions. Theoretical Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-021-00503-z Williams JL, Hufbauer RA, Miller TEX (2019) How Evolution Modifies the Variability of Range Expansion. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34, 903–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.05.012 | Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansions | Maxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Vincent Calcagno, Camille Duraj, Simon Fellous, Géraldine Groussier, Eric Lombaert, Ludovic Mailleret, Anaël Marchand, Elodie Vercken | <p style="text-align: justify;">As human influence reshapes communities worldwide, many species expand or shift their ranges as a result, with extensive consequences across levels of biological organization. Range expansions can be ranked on a con... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution | Inês Fragata | 2021-03-05 17:15:46 | View | |

02 Nov 2020

Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosisDavid Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265Temperature effects on virulence evolution of wMelPop Wolbachia in Drosophila melanogasterRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Shira Houwenhuyse and 3 anonymous reviewersMonnin et al. [1] here studied how Drosophila populations are affected when exposed to a high virulent endosymbiotic wMelPop Wolbachia strain and why virulent vertically transmitting endosymbionts persist in nature. This virulent wMelPop strain has been described to be a blocker of dengue and other arboviral infections in arthropod vector species, such as Aedes aegypti. Whereas it can thus function as a mutualistic symbiont, it here acts as an antagonist along the mutualism-antagonism continuum symbionts operate. The wMelPop strain is not a natural occurring strain in Drosophila melanogaster and thus the start of this experiment can be seen as a novel host-pathogen association. Through experimental evolution of 17 generations, the authors studied how high temperature affects wMelPop Wolbachia virulence and Drosophila melanogaster survival. The authors used Drosophila strains that were selected for late reproduction, given that this should favor evolution to a lower virulence. Assumptions for this hypothesis are not given in the manuscript here, but it can indeed be assumed that energy that is assimilated to symbiont tolerance instead of reproduction may lead to reduced virulence evolution. This has equally been suggested by Reyserhove et al. [2] in a dynamics energy budget model tailored to Daphnia magna virulence evolution upon a viral infection causing White fat Cell disease, reconstructing changing environments through time. References [1] Monnin, D., Kremer, N., Michaud, C., Villa, M., Henri, H., Desouhant, E. and Vavre, F. (2020) Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis. bioRxiv, 2020.04.26.062265, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265 | Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis | David Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre | <p>Evolutionary theory predicts that vertically transmitted symbionts are selected for low virulence, as their fitness is directly correlated to that of their host. In contrast with this prediction, the Wolbachia strain wMelPop drastically reduces... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Species interactions | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-04-29 19:16:56 | View | |

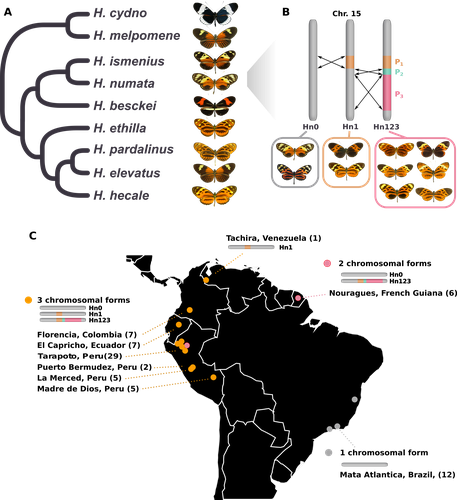

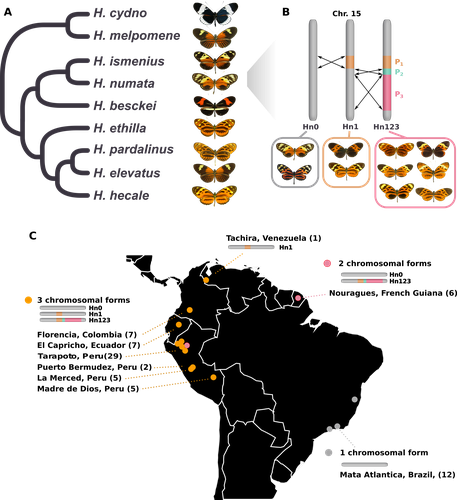

30 Mar 2023

Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow in a butterflyMaría Ángeles Rodríguez de Cara, Paul Jay, Quentin Rougemont, Mathieu Chouteau, Annabel Whibley, Barbara Huber, Florence Piron-Prunier, Renato Rogner Ramos, André V. L. Freitas, Camilo Salazar, Karina Lucas Silva-Brandão, Tatiana Texeira Torres, Mathieu Joron https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.29.462348Is genetic diversity enhanced by a supergene?Recommended by Chris Jiggins based on reviews by Christelle Fraïsse and 2 anonymous reviewersThe butterfly species Heliconius numata has a remarkable wing pattern polymorphism, with multiple pattern morphs all controlled by a single genetic locus, which harbours multiple inversions. Each morph is a near-perfect mimic of a species in the fairly distantly related genus of butterflies, Melinaea. The article by Rodríguez de Cara et al (2023) argues that the balanced polymorphism at this single wing patterning locus actually has a major effect on genetic diversity across the whole genome. First, polymorphic populations within H. numata are more dioverse than those without polymorphism. Second, H. numata is more genetically diverse than other related species and finally reconstruction of historical demography suggests that there has been a recent increase in effective population size, putatively associated with the acquisition of the supergene polymorphism. The supergene itself generates disassortative mating, such that morphs prefer to mate with others dissimilar to themselves - in this way it is similar to mechanisms for preventing inbreeding such as self-incompatibility loci in plants. This provides a potential mechanism whereby non-random mating patterns could increase effective population size. The authors also explore this mechanism using forward simulations, and show that mating patterns at a single locus can influence linked genetic diversity over a large scale. Overall, this is an intriguing study, which suggests a far more widespread genetic impact of a single locus than might be expected. There are interesting parallels with mechanisms of inbreeding prevention in plants, such as the Pin/Thrum polymorphism in Primula, which also rely on mating patterns determined by a single locus but presumably also influence genetic diversity genome-wide by promoting outbreeding. REFERENCES Rodríguez de Cara MÁ, Jay P, Rougemont Q, Chouteau M, Whibley A, Huber B, Piron-Prunier F, Ramos RR, Freitas AVL, Salazar C, Silva-Brandão KL, Torres TT, Joron M (2023) Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow. bioRxiv, 2021.09.29.462348, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.29.462348 | Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow in a butterfly | María Ángeles Rodríguez de Cara, Paul Jay, Quentin Rougemont, Mathieu Chouteau, Annabel Whibley, Barbara Huber, Florence Piron-Prunier, Renato Rogner Ramos, André V. L. Freitas, Camilo Salazar, Karina Lucas Silva-Brandão, Tatiana Texeira Torres, M... | <p style="text-align: justify;">Selection shapes genetic diversity around target mutations, yet little is known about how selection on specific loci affects the genetic trajectories of populations, including their genomewide patterns of diversity ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics | Chris Jiggins | 2021-10-13 17:54:33 | View | |

23 Nov 2020

Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mitesMiguel A. Cruz, Sara Magalhães, Élio Sucena, Flore Zélé https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.29.178699Speciation in spider mites: disentangling the roles of Wolbachia-induced vs. nuclear mating incompatibilitiesRecommended by Jan Engelstaedter based on reviews by Wolfgang Miller and 1 anonymous reviewerCytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) is a mating incompatibility that is induced by maternally inherited endosymbionts in many arthropods. These endosymbionts include, most famously, the alpha-proteobacterium Wolbachia pipientis (Yen & Barr 1971; Werren et al. 2008) but also the Bacteroidetes bacterium Cardinium hertigii (Zchori-Fein et al. 2001), a gamma-proteobacterium of the genus Rickettsiella (Rosenwald et al. 2020) and another, as yet undescribed alpha-proteobacterium (Takano et al. 2017). CI manifests as embryonic mortality in crosses between infected males and females that are uninfected or infected with a different strain, whereas embryos develop normally in all other crosses. This phenotype may enable the endosymbionts to spread rapidly within their host population. Exploiting this, CI-inducing Wolbachia are being harnessed to control insect-borne diseases (e.g., O'Neill 2018). Much progress elucidating the genetic basis and developmental mechanism of CI has been made in recent years, but many open questions remain (Shropshire et al. 2020). References Bordenstein, S. R., O'Hara, F. P., and Werren, J. H. (2001). Wolbachia-induced incompatibility precedes other hybrid incompatibilities in Nasonia. Nature, 409(6821), 707-710. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/35055543 | Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mites | Miguel A. Cruz, Sara Magalhães, Élio Sucena, Flore Zélé | <p>Wolbachia are widespread maternally-inherited bacteria suggested to play a role in arthropod host speciation through induction of cytoplasmic incompatibility, but this hypothesis remains controversial. Most studies addressing Wolbachia-induced ... | Evolutionary Ecology, Hybridization / Introgression, Life History, Reproduction and Sex, Speciation, Species interactions | Jan Engelstaedter | 2020-07-09 10:18:28 | View | ||

22 Mar 2022

Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus CorbiculaVastrade M., Etoundi E., Bournonville T., Colinet M., Debortoli N., Hedtke S.M., Nicolas E., Pigneur L.-M., Virgo J., Flot J.-F., Marescaux J. and Van Doninck K. https://doi.org/10.1101/590836Strange reproductive modes and population geneticsRecommended by Chris Jiggins based on reviews by Arnaud Estoup, Simon Henry Martin and 2 anonymous reviewersThere are many organisms that are asexual or have unusual modes of reproduction. One such quasi-sexual reproductive mode is androgenesis, in which the offspring, after fertilization, inherits only the entire paternal nuclear genome. The maternal genome is ditched along the way. One group of organisms which shows this mode of reproduction are clams in the genus Corbicula, some of which are androecious, while others are dioecious and sexual. The study by Vastrade et al. (2022) describes population genetic patterns in these clams, using both nuclear and mitochondrial sequence markers. In contrast to what might be expected for an asexual lineage, there is evidence for significant genetic mixing between populations. In addition, there is high heterozygosity and evidence for polyploidy in some lineages. Overall, the picture is complicated! However, what is clear is that there is far more genetic mixing than expected. One possible mechanism by which this could occur is 'nuclear capture' where there is a mixing of maternal and paternal lineages after fertilization. This can sometimes occur as a result of hybridization between 'species', leading to further mixing of divergent lineages. Thus the group is clearly far from an ancient asexual lineage - recombination and mixing occur with some regularity. The study also analyzed recent invasive populations in Europe and America. These had reduced genetic diversity, but also showed complex patterns of allele sharing suggesting a complex origin of the invasive lineages. In the future, it will be exciting to apply whole genome sequencing approaches to systems such as this. There are challenges in interpreting a handful of sequenced markers especially in a system with polyploidy and considerable complexity, and whole-genome sequencing could clarify some of the outstanding questions, Overall, this paper highlights the complex genetic patterns that can result through unusual reproductive modes, which provides a challenge for the field of population genetics and for the recognition of species boundaries. References Vastrade M, Etoundi E, Bournonville T, Colinet M, Debortoli N, Hedtke SM, Nicolas E, Pigneur L-M, Virgo J, Flot J-F, Marescaux J, Doninck KV (2022) Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus Corbicula. bioRxiv, 590836, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/590836 | Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus Corbicula | Vastrade M., Etoundi E., Bournonville T., Colinet M., Debortoli N., Hedtke S.M., Nicolas E., Pigneur L.-M., Virgo J., Flot J.-F., Marescaux J. and Van Doninck K. | <p style="text-align: justify;">“Occasional” sexuality occurs when a species combines clonal reproduction and genetic mixing. This strategy is predicted to combine the advantages of both asexuality and sexuality, but its actual consequences on the... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Hybridization / Introgression, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Chris Jiggins | 2019-03-29 15:42:56 | View | |

12 Jun 2018

Transgenerational cues about local mate competition affect offspring sex ratios in the spider mite Tetranychus urticaeAlison B. Duncan, Cassandra Marinosci, Céline Devaux, Sophie Lefèvre, Sara Magalhães, Joanne Griffin, Adeline Valente, Ophélie Ronce, Isabelle Olivieri https://doi.org/10.1101/240127Maternal effects in sex-ratio adjustmentRecommended by Dries Bonte based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersOptimal sex ratios have been topic of extensive studies so far. Fisherian 1:1 proportions of males and females are known to be optimal in most (diploid) organisms, but many deviations from this golden rule are observed. These deviations not only attract a lot of attention from evolutionary biologists but also from population ecologists as they eventually determine long-term population growth. Because sex ratios are tightly linked to fitness, they can be under strong selection or plastic in response to changing demographic conditions. Hamilton [1] pointed out that an equality of the sex ratio breaks down when there is local competition for mates. Competition for mates can be considered as a special case of local resource competition. In short, this theory predicts females to adjust their offspring sex ratio conditional on cues indicating the level of local mate competition that their sons will experience. When cues indicate high levels of LMC mothers should invest more resources in the production of daughters to maximise their fitness, while offspring sex ratios should be closer to 50:50 when cues indicate low levels of LMC. References [1] Hamilton, W. D. (1967). Extraordinary Sex Ratios. Science, 156(3774), 477–488. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3774.477 | Transgenerational cues about local mate competition affect offspring sex ratios in the spider mite Tetranychus urticae | Alison B. Duncan, Cassandra Marinosci, Céline Devaux, Sophie Lefèvre, Sara Magalhães, Joanne Griffin, Adeline Valente, Ophélie Ronce, Isabelle Olivieri | <p style="text-align: justify;">In structured populations, competition between closely related males for mates, termed Local Mate Competition (LMC), is expected to select for female-biased offspring sex ratios. However, the cues underlying sex all... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Dries Bonte | 2017-12-29 16:10:32 | View | |

07 Aug 2023

Pollen-feeding delays reproductive senescence and maintains toxicity of Heliconius eratoErika C. Pinheiro de Castro, Josie McPherson, Glennis Jullian, Anniina L. K. Mattila, Søren Bak, Stephen Montgomery, Chris Jiggins https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.13.523799Impact of pollen-feeding on egg-laying and cyanogenic glucoside abundance in red postman butterfliesRecommended by Adriana Briscoe based on reviews by Carol Boggs, Caroline Mueller and 1 anonymous reviewerGrowth, development and reproduction in animals are all limited by dietary nutrients. Expansion of an organism’s diet to sources not accessible to closely related species reduces food competition, and eases the constraints of nutrient-limited diets. Adult butterflies are herbivorous insects known to feed primarily on nectar from flowers, which is rich in sugars but poor in amino acids. Only certain species in the genus Heliconius are known to also feed on pollen, which is especially rich in amino acids, and is known to prolong their lives by several months. The ability to digest pollen in Heliconius has been linked to specialized feeding behaviors (Krenn et al. 2009) and extra-oral digestion using enzymes, possibly including duplicated copies of cocoonase (Harpel et al. 2016; Smith et al. 2016 and 2018), a protease used by some moths to digest silk upon eclosion from their cocoons. In this reprint, Pinheiro de Castro and colleagues investigated the impact of artificial and natural diets on egg-laying ability, body weight, and cyanogenic glucoside abundance in adult Heliconius erato butterflies of both sexes. Previous studies (Dunlap-Pianka et al. 1981) in H. charithonia demonstrated that access to dietary pollen led to extended egg-laying ability among adult female butterflies compared to females deprived of pollen, and compared to Dryas iulia females which feed only on nectar. In the current study, Pinheiro de Castro et al. (2023) examine the impact of diet on both young and old H. erato, over a longer period of time than the earlier work, highlighting the importance of extending the time period over which effects are evaluated. In addition to extending egg-laying ability in older females, the authors found that pollen in the diet appeared to maintain older female body weight, presumably because the pollen contained nutrients depleted during egg-laying. The authors then investigated the effects of nutrition on the production of cyanogenic glycoside defenses. Heliconius are aposematic butterflies that sequester cyanide-forming defense chemicals from food plants as larvae or synthesize these compounds de novo. The authors found the abundance of cyanogenic glycosides to be significantly greater in butterflies with access to pollen, but again only in older females. Curiously, field studies of male and female H. charithonia butterflies found that females in the wild collected more pollen than males (Mendoza-Cuenca and Macías-Ordóñez 2005). Taken together, these new findings raise the intriguing possibility that females collect more pollen than males, in part, because pollen has a bigger impact on female survival and reproduction. A small limitation of the study is the use of wing length, rather than body weight, at the zero time point. But the trend is clear in both males and females, and it adds supporting detail to the efficacy of pollen feeding as an unusual strategy for increasing fertility and survival in Heliconius butterflies.

References | Pollen-feeding delays reproductive senescence and maintains toxicity of Heliconius erato | Erika C. Pinheiro de Castro, Josie McPherson, Glennis Jullian, Anniina L. K. Mattila, Søren Bak, Stephen Montgomery, Chris Jiggins | <p>Dietary shifts may act to ease energetic constraints and allow organisms to optimise life-history traits. Heliconius butterflies differ from other nectar-feeders due to their unique ability to digest pollen, which provides a reliable source of ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Adriana Briscoe | 2023-02-07 12:59:54 | View | |

30 Oct 2023

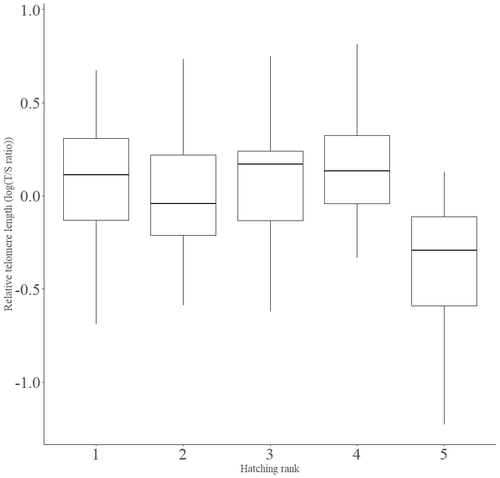

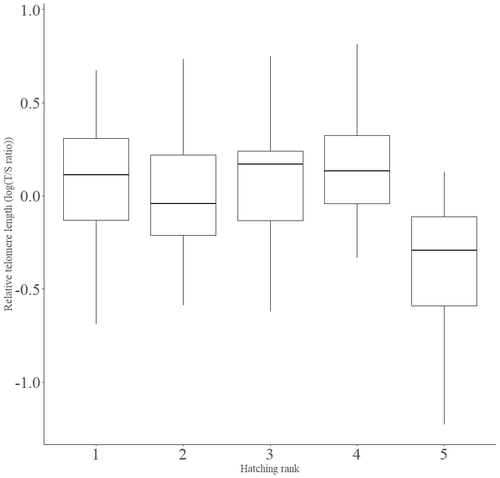

Telomere length vary with sex, hatching rank and year of birth in little owls, Athene noctuaFrançois Criscuolo, Inès Fache, Bertrand Scaar, Sandrine Zahn, Josefa Bleu https://doi.org/10.32942/X2BS3SDeciphering the relative contribution of environmental and biological factors driving telomere length in nestlingsRecommended by Jean-François Lemaitre based on reviews by Florentin Remot and 1 anonymous reviewerThe search for physiological markers of health and survival in wild animal populations is attracting a great deal of interest. At present, there is no (and may never be) consensus on such a single, robust marker but of all the proposed physiological markers, telomere length is undoubtedly the most widely studied in the field of evolutionary ecology (Monaghan et al., 2022). Broadly speaking, telomeres are non-coding DNA sequences located at the end of chromosomes in eukaryotes, protecting genomic DNA against oxidative stress and various detrimental processes (e.g. DNA end-joining) and thus maintaining genome stability (Blackburn et al., 2015). However, in most somatic cells from the vast majority of the species, telomere sequences are not replicated and telomere length progressively declines with increased age (Remot et al., 2022). This shortening of telomere length upon a critical level is causally linked to cellular senescence and has been invoked as one of the primary causes of the aging process (López-Otín et al., 2023). Studies performed in both captive and wild populations of animals have further demonstrated that short telomeres (or telomere sequences with a fast attrition rate) are to some extent associated with an increased risk of mortality, even if the magnitude of this association largely differs between species and populations (Wilbourn et al., 2018). The repeated observations of associations between telomere length and mortality risk have called for studies seeking to identify the ecological and biological factors that – beyond chronological age – shape the between-individual variability in telomere length. A wide spectrum of environmental stressors such as the level of exposure to pathogens or the degree of human disturbances has been proposed as possible modulators of telomere dynamics (see Chatelain et al., 2019). However, within species, the relative contribution of various ecological and biological factors on telomere length has been rarely quantified. In that context, the study of Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) constitutes a timely attempt to decipher the relative contribution of environmental and biological factors driving telomere length in nestlings (i.e. when individuals are between 15 and 35 days of age) from a wild population of little owls, Athene noctua. In addition to chronological age, Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) analysed the effects of two environmental variables (i.e. cohort and habitat quality) as well as three life history traits (i.e. hatching rank, sex and body condition). Among these traits, sex was found to impact nestling’s telomere length with females carrying longer telomeres than males. Traditionally, the among-individuals variability in telomere length during the juvenile period is interpreted as a direct consequence of differences in growth allocation. Fast-growing individuals are typically supposed to undergo more cell divisions and a higher exposure to oxidative stress, which ultimately shortens telomeres (Monaghan & Ozanne, 2018). Whether - despite a slightly female-biased sexual size dimorphism - male little owls display a condensed period of fast growth that could explain their shorter telomere is yet to be determined. Future studies should also explore the consequences of these sex differences in telomere length in terms of mortality risk. In birds, it has been observed that telomere length during early life can predict lifespan (see Heidinger et al., 2012 in zebra finches, Taeniopygia guttata), suggesting that females little owls might live longer than their conspecific males. Yet, adult mortality is generally female-biased in birds (Liker & Székely, 2005) and whether little owls constitute an exception to this rule - possibly mediated by sex-specific telomere dynamics - remains to be explored. Quite surprisingly, the present study in little owls did not evidence any clear effect of environmental conditions on nestling’s telomere length, at both temporal and special scales. While a trend for a temporal effect was detected with telomere length being slightly shorter for nestling born the last year of the study (out of 4 years analysed), habitat quality (measured by the proportion of meadow and orchards in the nest environment) had absolutely no impact on nestling telomere length. Recently published studies in wild populations of vertebrates have highlighted the detrimental effects of harsh environmental conditions on telomere length (e.g. Dupoué et al., 2022 in common lizards, Zootoca vivipara), arguing for a key role of telomere dynamics in the emerging field of conservation physiology. While we can recognize the relevance of such an integrative approach, especially in the current context of climate change, the study by Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) reminds us that the relationships between environmental conditions and telomere dynamics are far from straightforward. Depending on the species and its life history, telomere length in early life could indeed capture very different environmental signals. References Blackburn, E. H., Epel, E. S., & Lin, J. (2015). Human telomere biology: A contributory and interactive factor in aging, disease risks, and protection. Science, 350(6265), 1193-1198. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab3389 | Telomere length vary with sex, hatching rank and year of birth in little owls, *Athene noctua* | François Criscuolo, Inès Fache, Bertrand Scaar, Sandrine Zahn, Josefa Bleu | <p>Telomeres are non-coding DNA sequences located at the end of linear chromosomes, protecting genome integrity. In numerous taxa, telomeres shorten with age and telomere length (TL) is positively correlated with longevity. Moreover, TL is also af... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Jean-François Lemaitre | 2023-03-07 09:44:32 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer