Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▲ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

13 Jan 2019

Why cooperation is not running awayFélix Geoffroy, Nicolas Baumard, Jean-Baptiste André https://doi.org/10.1101/316117A nice twist on partner choice theoryRecommended by Erol Akcay based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersIn this paper, Geoffroy et al. [1] deal with partner choice as a mechanism of maintaining cooperation, and argues that rather than being unequivocally a force towards improved payoffs to everyone through cooperation, partner choice can lead to “over-cooperation” where individuals can evolve to invest so much in cooperation that the costs of cooperating partially or fully negate the benefits from it. This happens when partner choice is consequential and effective, i.e., when interactions are long (so each decision to accept or reject a partner is a bigger stake) and when meeting new partners is frequent when unpaired (so that when one leaves an interaction one can find a new partner quickly). Geoffroy et al. [1] show that this tendency to select for overcooperation under such regimes can be counteracted if individuals base their acceptance-rejection of partners not just on the partner cooperativeness, but also on their own. By using tools from matching theory in economics, they show that plastic partner choice generates positive assortment between cooperativeness of the partners, and in the extreme case of perfectly assortative pairings, makes the pair the unit of selection, which selects for maximum total payoff. References [1] Geoffroy, F., Baumard, N., & Andre, J.-B. (2019). Why cooperation is not running away. bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/316117 | Why cooperation is not running away | Félix Geoffroy, Nicolas Baumard, Jean-Baptiste André | <p>A growing number of experimental and theoretical studies show the importance of partner choice as a mechanism to promote the evolution of cooperation, especially in humans. In this paper, we focus on the question of the precise quantitative lev... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Theory | Erol Akcay | 2018-05-15 10:32:51 | View | |

08 Feb 2019

Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenesAnouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo https://doi.org/10.1101/337477E5, the third oncogene of PapillomavirusRecommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Leonardo de Oliveira Martins and 1 anonymous reviewerPapillomaviruses (PVs) infect almost all mammals and possibly amniotes and bony fishes. While most of them have no significant effects on the hosts, some induce physical lesions. Phylogeny of PVs consists of a few crown groups [1], among which AlphaPVs that infect primates including human have been well studied. They are associated to largely different clinical manifestations: non-oncogenic PVs causing anogenital warts, oncogenic and non-oncogenic PVs causing mucosal lesions, and non-oncogenic PVs causing cutaneous warts. References [1] Bravo, I. G., & Alonso, Á. (2004). Mucosal human papillomaviruses encode four different E5 proteins whose chemistry and phylogeny correlate with malignant or benign growth. Journal of virology, 78, 13613-13626. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13613-13626.2004 | Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenes | Anouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo | <p>The clinical presentations of papillomavirus (PV) infections come in many different flavors. While most PVs are part of a healthy skin microbiota and are not associated to physical lesions, other PVs cause benign lesions, and only a handful of ... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Hirohisa Kishino | 2018-06-04 16:15:39 | View | |

10 Jan 2020

Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shiftsGilles Didier https://doi.org/10.1101/376756Fitting diversification models on undated or partially dated treesRecommended by Nicolas Lartillot based on reviews by Amaury Lambert, Dominik Schrempf and 1 anonymous reviewerPhylogenetic trees can be used to extract information about the process of diversification that has generated them. The most common approach to conduct this inference is to rely on a likelihood, defined here as the probability of generating a dated tree T given a diversification model (e.g. a birth-death model), and then use standard maximum likelihood. This idea has been explored extensively in the context of the so-called diversification studies, with many variants for the models and for the questions being asked (diversification rates shifting at certain time points or in the ancestors of particular subclades, trait-dependent diversification rates, etc). References [1] Didier, G. (2020) Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shifts. bioRxiv, 376756, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/376756 | Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shifts | Gilles Didier | <p>Dating the tree of life is a task far more complicated than only determining the evolutionary relationships between species. It is therefore of interest to develop approaches apt to deal with undated phylogenetic trees. The main result of this ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Macroevolution | Nicolas Lartillot | 2019-01-30 11:28:58 | View | |

11 Dec 2020

Quantifying transmission dynamics of acute hepatitis C virus infections in a heterogeneous population using sequence dataGonche Danesh, Victor Virlogeux, Christophe Ramière, Caroline Charre, Laurent Cotte, Samuel Alizon https://doi.org/10.1101/689158Phylodynamics of hepatitis C virus reveals transmission dynamics within and between risk groups in LyonRecommended by David Rasmussen based on reviews by Chris Wymant and Louis DuPlessisGenomic epidemiology seeks to better understand the transmission dynamics of infectious pathogens using molecular sequence data. Phylodynamic methods have given genomic epidemiology new power to track the transmission dynamics of pathogens by combining phylogenetic analyses with epidemiological modeling. In recent year, applications of phylodynamics to chronic viral infections such as HIV and hepatitis C virus (HVC) have provided some of the best examples of how phylodynamic inference can provide valuable insights into transmission dynamics within and between different subpopulations or risk groups, allowing for more targeted interventions. References [1] Rasmussen, D. A., Volz, E. M., and Koelle, K. (2014). Phylodynamic inference for structured epidemiological models. PLoS Comput Biol, 10(4), e1003570. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003570 | Quantifying transmission dynamics of acute hepatitis C virus infections in a heterogeneous population using sequence data | Gonche Danesh, Victor Virlogeux, Christophe Ramière, Caroline Charre, Laurent Cotte, Samuel Alizon | <p>Opioid substitution and syringes exchange programs have drastically reduced hepatitis C virus (HCV) spread in France but HCV sexual transmission in men having sex with men (MSM) has recently arisen as a significant public health concern. The fa... |  | Evolutionary Epidemiology, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | David Rasmussen | 2019-07-11 13:37:23 | View | |

04 Aug 2023

Sensitive windows for within- and trans-generational plasticity of anti-predator defencesJuliette Tariel-Adam; Émilien Luquet; Sandrine Plénet https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/mr8huSensitive windows for phenotypic plasticity within and across generations; where empirical results do not meet the theory but open a world of possibilitiesRecommended by Benoit Pujol based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker, Timothée Bonnet and Willem FrankenhuisIt is easy to define phenotypic plasticity as a mechanism by which traits change in response to a modification of the environment. Many complex mechanisms are nevertheless involved with plastic responses, their strength, and stability (e.g., reliability of cues, type of exposure, genetic expression, epigenetics). It is rather intuitive to think that environmental cues perceived at different stages of development will logically drive different phenotypic responses (Fawcett and Frankenhuis 2015). However, it has proven challenging to try and explain, or model how and why different effects are caused by similar cues experienced at different developmental or life stages (Walasek et al. 2022). The impact of these ‘sensitive windows’ on the stability of plastic responses within or across generations remains unclear. In their paper entitled “Sensitive windows for within- and trans-generational plasticity of anti-predator defences”, Tariel-Adam (2023) address this question. In this paper, Tariel et al. acknowledge the current state of the art, i.e., that some traits influenced by the environment at early life stages become fixed later in life (Snell-Rood et al. 2015) and that sensitive windows are therefore more likely to be observed during early stages of development. Constructive exchanges with the reviewers illustrated that Tariel et al. presented a clear picture of the knowledge on sensitive windows from a conceptual and a mechanistic perspective, thereby providing their study with a strong and elegant rationale. Tariel et al. outlined that little is known about the significance of this scenario when it comes to transgenerational plasticity. Theory predicts that exposure late in the life of parents should be more likely to drive transgenerational plasticity because the cue perceived by parents is more likely to be reliable if time between parental exposure and offspring expression is short (McNamara et al. 2016). I would argue that although sensible, this scenario is likely oversimplifying the complexity of evolutionary, ecological, and inheritance mechanisms at play (Danchin et al. 2018). Tariel-Adam et al. (2023) point out in their paper how the absence of experimental results limits our understanding of the evolutionary and adaptive significance of transgenerational plasticity and decided to address this broad question. Tariel-Adam et al. (2023) used the context of predator-prey interactions, which is a powerful framework to evaluate the temporality of predator cues and prey responses within and across generations (Sentis et al. 2018). They conducted a very elegant experiment whereby two generations of freshwater snails Physa acuta were exposed to crayfish predator cues at different developmental windows. They triggered the within-generation phenotypic plastic response of inducible defences (e.g., shell thickness) and identified sensitive windows as to evaluate their role in within-generation phenotypic plasticity versus transgenerational plasticity. They used different linear models, which lead to constructive exchanges with reviewers, and between reviewers, well trained on these approaches, in particular on effect sizes, that improved the paper by pushing the discussion all the way towards a consensus. Tariel-Adam et al. (2023) results showed that the phenotypic plastic response of different traits was associated with different sensitive windows. Although early-life development was confirmed to be a sensitive window, it was far from being the only developmental stage driving within-generation plastic responses of defence traits. This finding contributes to change our views on plasticity because where theoretical models predict early- and late-life sensitive windows, empirical results gathered here present a more continuous opportunity for sensitive windows over the lifetime of freshwater snails. This is likely because multifactorial mechanisms drive the reliability and adaptive significance of predator cues. To me, this paper most original contribution lies probably in the empirical investigation of sensitive windows underlying transgenerational plasticity. Their finding implies mechanistic ties between sensitive windows driving within-generation and transgenerational plasticity for some traits, but they also shed light on the possible independence of these processes. Although one may be disheartened by these findings illustrating the ability of nature to combine complex mechanisms in order to produce somewhat unpredictable scenarios, one can only find that this unlimited range of phenotypic plasticity scenarios is a wonder to investigate because much remains to be understood. As mentioned in the conclusion of the paper, the opportunity for sensitive windows to drive such a range of plastic responses may also be an opportunity for organisms to adapt to a wide range of environmental demands. References Danchin E, A Pocheville, O Rey, B Pujol, and S Blanchet (2019). Epigenetically facilitated mutational assimilation: epigenetics as a hub within the inclusive evolutionary synthesis. Biological Reviews, 94: 259-282. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12453 Fawcett TW, and WE Frankenhuis (2015). Adaptive Explanations for Sensitive Windows in Development. Frontiers in Zoology 12, S3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-9994-12-S1-S3 McNamara JM, SRX Dall, P Hammerstein, and O Leimar (2016). Detection vs. Selection: Integration of Genetic, Epigenetic and Environmental Cues in Fluctuating Environments. Ecology Letters 19, 1267–1276. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12663 Sentis A, R Bertram, N Dardenne, et al. (2018). Evolution without standing genetic variation: change in transgenerational plastic response under persistent predation pressure. Heredity 121, 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-018-0108-8 Snell-Rood EC, EM Swanson, and RL Young (2015). Life History as a Constraint on Plasticity: Developmental Timing Is Correlated with Phenotypic Variation in Birds. Heredity 115, 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2015.47 Tariel-Adam J, E Luquet, and S Plénet (2023). Sensitive windows for within- and trans-generational plasticity of anti-predator defences. OSF preprints, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/mr8hu Walasek N, WE Frankenhuis, and K Panchanathan (2022). An Evolutionary Model of Sensitive Periods When the Reliability of Cues Varies across Ontogeny. Behavioral Ecology 33, 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arab113 | Sensitive windows for within- and trans-generational plasticity of anti-predator defences | Juliette Tariel-Adam; Émilien Luquet; Sandrine Plénet | <p>Transgenerational plasticity could be an important mechanism for adaptation to variable environments in addition to within-generational plasticity. But its potential for adaptation may be restricted to specific developmental windows that are hi... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Benoit Pujol | 2022-11-14 08:08:27 | View | |

11 Mar 2020

Phylogenomic approaches reveal how a climatic inversion and glacial refugia shape patterns of diversity in an African rain forest tree speciesAndrew J. Helmstetter, Biowa E. N. Amoussou, Kevin Bethune, Narcisse G. Kandem, Romain Glèlè Kakaï, Bonaventure Sonké, Thomas L. P. Couvreur https://doi.org/10.1101/807727Remarkable insights into processes shaping African tropical tree diversityRecommended by Michael Pirie based on reviews by Miguel de Navascués, Lars Chatrou and Oscar Vargas based on reviews by Miguel de Navascués, Lars Chatrou and Oscar Vargas

Tropical biodiversity is immense, under enormous threat, and yet still poorly understood. Global climatic breakdown and habitat destruction are impacting on and removing this diversity before we can understand how the biota responds to such changes, or even fully appreciate what we are losing [1]. This is particularly the case for woody shrubs and trees [2] and for the flora of tropical Africa [3]. Helmstetter et al. [4] have taken a significant step to improve our understanding of African tropical tree diversity in the context of past climatic change. They have done so by means of a remarkably in-depth analysis of one species of the tropical plant family Annonaceae: Annickia affinis [5]. A. affinis shows a distribution pattern in Africa found in various plant (but interestingly not animal) groups: a discontinuity between north and south of the equator [6]. There is no obvious physical barrier to cause this discontinuity, but it does correspond with present day distinct northern and southern rainy seasons. Various explanations have been proposed for this discontinuity, set out as hypotheses to be tested in this paper: climatic fluctuations resulting in changes in plant distributions in the Pleistocene, or differences in flowering times or in ecological niche between northerly and southerly populations. These explanations are not mutually exclusive, but they can be tested using phylogenetic inference – if you can sample variable enough sequence data from enough individuals – complemented with analysis of ecological niches and traits. Using targeted sequence capture, the authors amassed a dataset representing 351 nuclear markers for 112 individuals of A. affinis. This dataset is impressive for a number of reasons: First, sampling such a species across such a wide range in tropical Africa presents numerous challenges of itself. Second, the technical achievement of using this still relatively new sequencing technique with a custom set of baits designed specifically for this plant family [7] is also considerable. The result is a volume of data that just a few years ago would not have been feasible to collect, and which now offers the possibility to meaningfully analyse DNA sequence variation within a species across numerous independent loci of the nuclear genome. This is the future of our research field, and the authors have ably demonstrated some of its possibilities. Using this data, they performed on the one hand different population genetic clustering approaches, and on the other, different phylogenetic inference methods. I would draw attention to their use and comparison of coalescence and network-based approaches, which can account for the differences between gene trees that might be expected between populations of a single species. The results revealed four clades and a consistent sequence of divergences between them. The authors inferred past shifts in geographic range (using a continuous state phylogeographic model), depicting a biogeographic scenario involving a dispersal north over the north/south discontinuity; and demographic history, inferring in some (but not all) lineages increases in effective population size around the time of the last glacial maximum, suggestive of expansion from refugia. Using georeferenced specimen data, they compared ecological niches between populations, discovering that overlap was indeed smallest comparing north to south. Just the phenology results were effectively inconclusive: far better data on flowering times is needed than can currently be harvested from digitised herbarium specimens. Overall, the results add to the body of evidence for the impact of Pleistocene climatic changes on population structure, and for niche differences contributing to the present day north/south discontinuity. However, they also paint a complex picture of idiosyncratic lineage-specific responses, even within a single species. With the increasing accessibility of the techniques used here we can look forward to more such detailed analyses of independent clades necessary to test and to expand on these conclusions, better to understand the nature of our tropical plant diversity while there is still opportunity to preserve it for future generations. References [1] Mace, G. M., Gittleman, J. L., and Purvis, A. (2003). Preserving the Tree of Life. Science, 300(5626), 1707–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1085510 | Phylogenomic approaches reveal how a climatic inversion and glacial refugia shape patterns of diversity in an African rain forest tree species | Andrew J. Helmstetter, Biowa E. N. Amoussou, Kevin Bethune, Narcisse G. Kandem, Romain Glèlè Kakaï, Bonaventure Sonké, Thomas L. P. Couvreur | <p>The world’s second largest expanse of tropical rain forest is in Central Africa and it harbours enormous species diversity. Population genetic studies have consistently revealed significant structure across central African rain forest plants, i... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Michael Pirie | 2019-10-29 15:19:36 | View | |

19 Jul 2021

Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasitesHannelore MacDonald, Erol Akçay, Dustin Brisson https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.13.435259Modelling parasitoid virulence evolution with seasonalityRecommended by Samuel Alizon based on reviews by Alex Best and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Alex Best and 2 anonymous reviewers

The harm most parasites cause to their host, i.e. the virulence, is a mystery because host death often means the end of the infectious period. For obligate killer parasites, or “parasitoids”, that need to kill their host to transmit to other hosts the question is reversed. Indeed, more rapid host death means shorter generation intervals between two infections and mathematical models show that, in the simplest settings, natural selection should always favour more virulent strains (Levin and Lenski, 1983). Adding biological details to the model modifies this conclusion and, for instance, if the relationship between the infection duration and the number of parasites transmission stages produced in a host is non-linear, strains with intermediate levels of virulence can be favoured (Ebert and Weisser 1997). Other effects, such as spatial structure, could yield similar effects (Lion and van Baalen, 2007). In their study, MacDonald et al. (2021) explore another type of constraint, which is seasonality. Earlier studies, such as that by Donnelly et al. (2013) showed that this constraint can affect virulence evolution but they had focused on directly transmitted parasites. Using a mathematical model capturing the dynamics of a parasitoid, MacDonald et al. (2021) show if two main assumptions are met, namely that at the end of the season only transmission stages (or “propagules”) survive and that there is a constant decay of these propagules with time, then strains with intermediate levels of virulence are favoured. Practically, the authors use delay differential equations and an adaptive dynamics approach to identify evolutionary stable strategies. As expected, the longer the short the season length, the higher the virulence (because propagule decay matters less). The authors also identify a non-linear relationship between the variation in host development time and virulence. Generally, the larger the variation, the higher the virulence because the parasitoid has to kill its host before the end of the season. However, if the variation is too wide, some hosts become physically impossible to use for the parasite, whence a decrease in virulence. Finally, MacDonald et ali. (2021) show that the consequence of adding trade-offs between infection duration and the number of propagules produced is in line with earlier studies (Ebert and Weisser 1997). These mathematical modelling results provide testable predictions for using well-described systems in evolutionary ecology such as daphnia parasitoids, baculoviruses, or lytic phages. Reference Donnelly R, Best A, White A, Boots M (2013) Seasonality selects for more acutely virulent parasites when virulence is density dependent. Proc R Soc B, 280, 20122464. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2464 Ebert D, Weisser WW (1997) Optimal killing for obligate killers: the evolution of life histories and virulence of semelparous parasites. Proc R Soc B, 264, 985–991. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1997.0136 Levin BR, Lenski RE (1983) Coevolution in bacteria and their viruses and plasmids. In: Futuyma DJ, Slatkin M eds. Coevolution. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc., 99–127. Lion S, van Baalen M (2008) Self-structuring in spatial evolutionary ecology. Ecol. Lett., 11, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01132.x MacDonald H, Akçay E, Brisson D (2021) Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasites. bioRxiv, 2021.03.13.435259, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.13.435259 | Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasites | Hannelore MacDonald, Erol Akçay, Dustin Brisson | <p style="text-align: justify;">The traditional mechanistic trade-offs resulting in a negative correlation between transmission and virulence are the foundation of nearly all current theory on the evolution of parasite virulence. Several ecologica... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Samuel Alizon | 2021-03-14 13:47:33 | View | |

16 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Evolutionary robotics simulations help explain why reciprocity is rare in nature.André J-B, Nolfi S 10.1038/srep32785Simulated robots and the evolution of reciprocityRecommended by Michael D Greenfield and Joël Meunier

Of the various forms of cooperative and altruistic behavior, reciprocity remains the most contentious. Humans certainly exhibit reciprocity – under certain circumstances – and various non-human animals behave in ways suggesting that they do as well. Thus, evolutionary biologists have sought to explain why non-relatives might engage in altruistic transactions when a substantial delay occurs between helping and compensation; i.e. an individual may be a donor today and a beneficiary tomorrow, or vice-versa. This quest, aided by game theory and computer modeling late in the past century, identified some strategies for reciprocal behavior that could work – in theory. But when biologists looked for confirmation of these strategies in animals they found little evidence that stood up to rigorous testing. In a recent paper André and Nolfi [1] offer a compelling reason for this observed rarity of reciprocity: Reciprocal behavior that animals might exhibit is a bit more complex than any of the game theoretic strategies, and even the simplest forms of realistic behavior would entail several nearly simultaneous mutations, an unlikely occurrence. André and Nolfi [1] relied on neural networks to test actors, robots that could evolve helping and reciprocal behavior from a basal level of selfishness. In an extensive series of simulations, they found that reciprocal behavior did not take hold in a population, largely because the various intermediates to full reciprocity were eliminated before the subsequent mutations occurred. The findings are satisfying given our current knowledge of animal behavior, but questions remain. Notably, how does one account for those rare cases in which reciprocity does meet all the criteria? The authors suggest some possibilities, but an analysis will await their next study. Reference [1] André J-B, Nolfi S. 2016. Evolutionary robotics simulations help explain why reciprocity is rare in nature. Scientific Reports 6:32785. doi: 10.1038/srep32785 | Evolutionary robotics simulations help explain why reciprocity is rare in nature. | André J-B, Nolfi S | The relative rarity of reciprocity in nature, contrary to theoretical predictions that it should be widespread, is currently one of the major puzzles in social evolution theory. Here we use evolutionary robotics to solve this puzzle. We show tha... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Theory | Michael D Greenfield | 2016-12-16 18:08:31 | View | |

17 May 2021

Relative time constraints improve molecular datingGergely J Szollosi, Sebastian Hoehna, Tom A Williams, Dominik Schrempf, Vincent Daubin, Bastien Boussau https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.17.343889Dating with constraintsRecommended by Cécile Ané based on reviews by David Duchêne and 1 anonymous reviewerEstimating the absolute age of diversification events is challenging, because molecular sequences provide timing information in units of substitutions, not years. Additionally, the rate of molecular evolution (in substitutions per year) can vary widely across lineages. Accurate dating of speciation events traditionally relies on non-molecular data. For very fast-evolving organisms such as SARS-CoV-2, for which samples are obtained over a time span, the collection times provide this external information from which we can learn the rate of molecular evolution and date past events (Boni et al. 2020). In groups for which the fossil record is abundant, state-of-the-art dating methods use fossil information to complement molecular data, either in the form of a prior distribution on node ages (Nguyen & Ho 2020), or as data modelled with a fossilization process (Heath et al. 2014). Dating is a challenge in groups that lack fossils or other geological evidence, such as very old lineages and microbial lineages. In these groups, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) events have been identified as informative about relative dates: the ancestor of the gene's donor must be older than the descendants of the gene's recipient. Previous work using HGTs to date phylogenies have used methodologies that are ad-hoc (Davín et al 2018) or employ a small number of HGTs only (Magnabosco et al. 2018, Wolfe & Fournier 2018). Szöllősi et al. (2021) present and validate a Bayesian approach to estimate the age of diversification events based on relative information on these ages, such as implied by HGTs. This approach is flexible because it is modular: constraints on relative node ages can be combined with absolute age information from fossil data, and with any substitution model of molecular evolution, including complex state-of-art models. To ease the computational burden, the authors also introduce a two-step approach, in which the complexity of estimating branch lengths in substitutions per site is decoupled from the complexity of timing the tree with branch lengths in years, accounting for uncertainty in the first step. Currently, one limitation is that the tree topology needs to be known, and another limitation is that constraints need to be certain. Users of this method should be mindful of the latter when hundreds of constraints are used, as done by Szöllősi et al. (2021) to date the trees of Cyanobacteria and Archaea. Szöllősi et al. (2021)'s method is implemented in RevBayes, a highly modular platform for phylogenetic inference, rapidly growing in popularity (Höhna et al. 2016). The RevBayes tutorial page features a step-by-step tutorial "Dating with Relative Constraints", which makes the method highly approachable. References: Boni MF, Lemey P, Jiang X, Lam TT-Y, Perry BW, Castoe TA, Rambaut A, Robertson DL (2020) Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Microbiology, 5, 1408–1417. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0771-4 Davín AA, Tannier E, Williams TA, Boussau B, Daubin V, Szöllősi GJ (2018) Gene transfers can date the tree of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2, 904–909. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0525-3 Heath TA, Huelsenbeck JP, Stadler T (2014) The fossilized birth–death process for coherent calibration of divergence-time estimates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, E2957–E2966. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319091111 Höhna S, Landis MJ, Heath TA, Boussau B, Lartillot N, Moore BR, Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F (2016) RevBayes: Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference Using Graphical Models and an Interactive Model-Specification Language. Systematic Biology, 65, 726–736. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syw021 Magnabosco C, Moore KR, Wolfe JM, Fournier GP (2018) Dating phototrophic microbial lineages with reticulate gene histories. Geobiology, 16, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/gbi.12273 Nguyen JMT, Ho SYW (2020) Calibrations from the Fossil Record. In: The Molecular Evolutionary Clock: Theory and Practice (ed Ho SYW), pp. 117–133. Springer International Publishing, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60181-2_8 Szollosi, G.J., Hoehna, S., Williams, T.A., Schrempf, D., Daubin, V., Boussau, B. (2021) Relative time constraints improve molecular dating. bioRxiv, 2020.10.17.343889, ver. 8 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.17.343889 Wolfe JM, Fournier GP (2018) Horizontal gene transfer constrains the timing of methanogen evolution. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2, 897–903. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0513-7 | Relative time constraints improve molecular dating | Gergely J Szollosi, Sebastian Hoehna, Tom A Williams, Dominik Schrempf, Vincent Daubin, Bastien Boussau | <p style="text-align: justify;">Dating the tree of life is central to understanding the evolution of life on Earth. Molecular clocks calibrated with fossils represent the state of the art for inferring the ages of major groups. Yet, other informat... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Cécile Ané | 2020-10-21 23:39:17 | View | |

05 Oct 2022

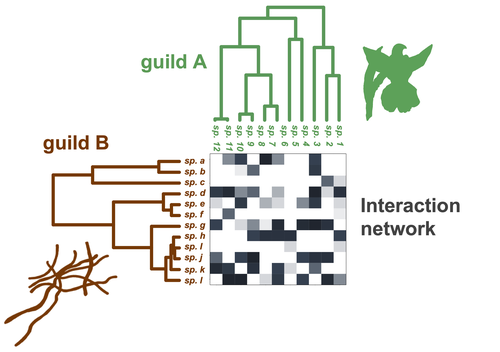

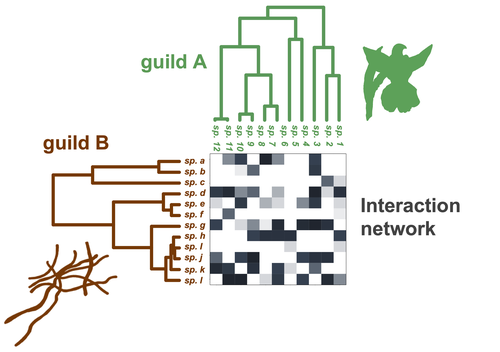

Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networksBenoît Perez-Lamarque, Odile Maliet, Benoît Pichon, Marc-André Selosse, Florent Martos, Hélène Morlon https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.30.458192Testing for phylogenetic signal in species interaction networksRecommended by Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer based on reviews by Joaquin Calatayud and Thomas GuillermeSpecies are immersed within communities in which they interact mutualistically, as in pollination or seed dispersal, or nonreciprocally, such as in predation or parasitism, with other species and these interactions play a paramount role in shaping biodiversity (Bascompte and Jordano 2013). Researchers have become increasingly interested in the processes that shape these interactions and how these influence community structure and responses to disturbances. Species interactions are often described using bipartite interaction networks and one important question is how the evolutionary history of the species involved influences the network, including whether there is phylogenetic signal in interactions, in other words whether closely related species interact with other closely related species (Bascompte and Jordano 2013, Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022). To address this question different approaches, correlative and model-based, have been developed to test for phylogenetic signal in interactions, although comparative analyses of the performance of these different metrics are lacking. In their article Perez-Lamarque et al. (2022) set out to test the statistical performance of two widely-used methods, Mantel tests and Phylogenetic Bipartite Linear Models (PBLM; Ives and Godfray 2006) using simulations. Phylogenetic signal is measured as the degree to which distance to the nearest common ancestor predicts the observed similarity in trait values among species. In species interaction networks, the data are actually the between-species dissimilarity among interacting species (Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022), and typical approaches to test for phylogenetic signal cannot be used. However, the Mantel test provides a useful means of analyzing the correlation between two distance matrices, the between-species phylogenetic distance and the between-species dissimilarity in interactions. The PBLM approach, on the other hand, assumes that interactions between species are influenced by unobserved traits that evolve along the phylogenies following a given phenotypic evolution model and the parameters of this model are interpreted in terms of phylogenetic signal (Ives and Godfray 2006). Perez-Lamarque et al (2022) found that the model-based PBLM approach has a high type-I error rate, in other words it often detected phylogenetic signal when there was none. The simple Mantel test was found to present a low type-I error rate and moderate statistical power. However, it tended to overestimate the degree to which species interact with dissimilar partners. In addition to the aforementioned analyses, the authors also tested whether the simple Mantel test was able to detect phylogenetic signal in interactions among species within a given clade in the phylogeny, as phylogenetic signal in species interactions may be localized within specific clades. The article concludes with general guidelines for users wishing to test phylogenetic signal in their interaction networks and illustrates them with an example of an orchid-mycorrhizal fungus network from the oceanic island of La Réunion (Martos et al 2012). This broadly accessible article provides a valuable analysis of the performance of tests of phylogenetic signal in interaction networks enabling users to make informed choices of the analytical methods they wish to employ, and provide useful and detailed guidelines. Therefore, the work should be of broad interest to researchers studying species interactions. References Bascompte J, Jordano P (2013) Mutualistic Networks. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400848720 Ives AR, Godfray HCJ (2006) Phylogenetic Analysis of Trophic Associations. The American Naturalist, 168, E1–E14. https://doi.org/10.1086/505157 Martos F, Munoz F, Pailler T, Kottke I, Gonneau C, Selosse M-A (2012) The role of epiphytism in architecture and evolutionary constraint within mycorrhizal networks of tropical orchids. Molecular Ecology, 21, 5098–5109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05692.x Perez-Lamarque B, Maliet O, Pichon B, Selosse M-A, Martos F, Morlon H (2022) Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks. bioRxiv, 2021.08.30.458192, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.30.458192 | Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks | Benoît Perez-Lamarque, Odile Maliet, Benoît Pichon, Marc-André Selosse, Florent Martos, Hélène Morlon | <p style="text-align: justify;">Whether interactions between species are conserved on evolutionary time-scales has spurred the development of both correlative and process-based approaches for testing phylogenetic signal in interspecific interactio... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer | 2022-03-10 13:48:15 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer