Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▲ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

04 Jul 2022

A genomic assessment of the marine-speciation paradox within the toothed whale superfamily DelphinoideaMichael V Westbury, Andrea A Cabrera, Alba Rey-Iglesia, Binia De Cahsan, David A. Duchêne, Stefanie Hartmann, Eline D Lorenzen https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.23.352286Reticulated evolution marks the rapid diversification of the DelphinoidaeRecommended by Michael C. Fontaine based on reviews by Christelle Fraïsse, Simon Henry Martin, Andrew Foote and 2 anonymous reviewersHistorically neglected or considered a rare aberration in animals under the biological species concept, interspecific hybridisation has by now been recognised to be taxonomically widespread, particularly in rapidly diversifying groups (Dagilis et al. 2021; Edelman & Mallet 2021; Mallet et al. 2016; Seehausen 2004). Yet the prevalence of introgressive hybridizations, its evolutionary significance, and its impact on species diversification remain a hot topic of research in evolutionary biology. The rapid increase in genomic resources now available for non-model species has significantly contributed to the detection of introgressive hybridization across taxa showing that reticulated evolution is far more common in the animal kingdom than historically considered. Yet, detecting it, quantifying its magnitude, and assessing its evolutionary significance remains a challenging endeavour with constantly evolving methodologies to better explore and exploit genomic data (Blair & Ané 2020; Degnan & Rosenberg 2009; Edelman & Mallet 2021; Hibbins & Hahn 2022). In the marine realm, the dearth of geographic barriers and the large dispersal abilities of pelagic species like cetaceans have raised the questions of how populations and species can diverge and adapt to distinct ecological conditions in face of potentially large gene-flow, the so-called marine speciation paradox (Bierne et al. 2003). Contemporaneous hybridization among cetacean species has been widely documented in nature despite large phenotypic differences (Crossman et al. 2016). The historical prevalence of reticulated evolution, its evolutionary significance, and how it might have impacted the evolutionary history and diversification of the cetaceans have however remained elusive so far. Recent phylogenomic studies suggested that introgression has been prevalent in cetacean evolutionary history with instances reported among baleen whales (mysticetes) (Árnason et al. 2018) and among toothed whales (odontocetes), especially in the rapidly diversifying dolphins family of the Delphininae (Guo et al. 2021; Moura et al. 2020). Analysing publicly available whole-genome data from nine cetacean species across three families of Delphinoidae – dolphins, porpoises, and monondontidae – using phylogenomics and demo-genetics approaches, Westbury and colleagues (2022) take a step further in documenting that evolution among these species has been far from a simple bifurcating tree. Instead, their study describes widespread occurrences of introgression among Delphinoidae, drawing a complex picture of reticulated evolutionary history. After describing major topology discordance in phylogenetic gene trees along the genome, the authors use a panel of approaches to disentangle introgression from incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), the two most common causes of tree topology discordances (Hibbins & Hahn 2022). Applying popular tests that separate introgression from ILS, such as the Patterson’s D (a.k.a. ABBA-BABA) test (Durand et al. 2011; Green et al. 2010), QuIBL (Edelman et al. 2019), and D-FOIL (Pease & Hahn 2015), the authors report that signals of introgression are present in the genomes of most (if not all) the cetacean species included in their study. However, this picture needs to be nuanced. Most introgression signals seem to echo old introgression events that occurred primarily among ancestors. This is suggested by the differential signals of topology discordance along the genome when considering sliding windows along the genome of varying sizes (50kb, 100kb, and 1Mb), and by patterns of excess derived allele sharing along branches of the species tree, as captured by the f-branch test (Malinsky et al. 2021; Malinsky et al. 2018). The authors further investigated the dynamic of cessation of gene flow (and/or ILS) between species using the F1 hybrid PSMC (or hPSMC) approach (Cahill et al. 2016). By estimating the cross-coalescent rates (CRR) between species pairs with time in light of previously estimated species divergence times (McGowen et al. 2020), the authors report that gene flow (and/or ILS) most likely has stopped by now among most species, but it may have lasted for more than half of the time since the species split from each other. According to the author, this result may reflect the slow process by which reproductive isolation would have evolved between cetacean lineages, and that species isolation was marked by significant introgression events. Now, while the present study provides a good overview of how complex is the reticulated evolutionary history of the Delphinoidae, getting a complete picture will require overcoming a few important limitations. The first ones are methodological and related to the phylogenomic analyses. Given the sampling design with one diploid genome per species, the authors could not phase the data into the parental haplotypes, but instead relied on a majority consensus creating mosaic haploidized genomes representing a mixture between the two parental copies. Moreover, by using large genomic windows (≥50kb) that likely span multiple independent loci, phylogenetic analyses in windows encompassed distinct phylogenetic signals, potentially leading to bias and inaccuracy in the inferences. Thawornwattana et al (2018) previously showed that this “concatenation approach” could significantly impact phylogenetic inferences. They proposed instead to use loci small enough to minimise the risk of intra-locus recombination and to consider them in blocks of non-recombining loci along the genome in order to conduct phylogenetic analysed, ideally under the multi-species coalescent (MSC) that can account for ILS (e.g. BPP; Flouri et al. 2018; Jiao et al. 2020; Yang 2015). Such an approach applied to the diversification of the Delphinidae may reveal substantial changes compared to the currently admitted species tree. Inaccuracy in the species tree estimation may have a major impact on the introgression analyses conducted in this study since the species tree and branching order must be supplied in the introgression analyses to properly disentangle introgression from ILS. Here, the authors rely on the tree topology that was previously estimated in McGowen et al. (2020), which they also recovered using their consensus estimation from ASTRAL-III (Zhang et al. 2018). While the methodologies accounted to a certain extent for ILS, albeit with potential bias induced by the concatenation approach, they ignore the presumably large amount of introgression among species during the diversification process. Estimating species branching order while ignoring introgression can lead to major bias in the phylogenetic inference and can lead to incorrect topologies. Even if these MSC-based methods account for ILS, inferences can become very inaccurate or even break down as gene flow increases (see for ex. Jiao et al. 2020; Müller et al. in press; Solís-Lemus et al. 2016). Dedicated approaches have been developed to model explicitly introgression together with ILS to estimate phylogenetic networks (Blair & Ané 2020; Rabier et al. 2021) or in isolation-with-migration model (Müller et al. in press; Wang et al. 2020). Future studies revisiting the reticulated evolutionary history of the Delphinoidae with such approaches may not only precise the species branching order, but also deliver a finer view of the magnitude and prevalence of introgression during the evolutionary history of these species. A final part of Westbury et al. (2022)'s study set out to test whether historical periods of low abundance could have facilitated hybridization among Delphinoidae species. During these periods of low abundance, species may encounter only a limited number of conspecifics and may consider individuals from other species as suitable mating partners, leading to hybridisation (Crossman et al. 2016; Edwards et al. 2011; Westbury et al. 2019). The authors tested this hypothesis by considering genome-wide genetic diversity (or heterozygosity) as a proxy of historical effective population size (Ne), itself as a proxy of the evolution of census size with time. They also try to link historical Ne variation (from PSMC, Li & Durbin 2011) with their estimated time to cessation of gene flow or ILS (from the CRR of hPSMC). However, no straightforward relationship was found between the genetic diversity and the propensity of species to hybridize, nor was there any clear link between Ne variation through time and the cessation of gene flow or ILS. Such a lack of relationship may not come as a surprise, since the determinants of genome-wide genetic diversity and its variation through evolutionary time-scale are far more diverse and complex than just a direct link with hybridization, introgression, or even with the census population size. In fact, genetic diversity results from the balance between all the evolutionary processes at play in the species' evolutionary history (see the review of Ellegren & Galtier 2016). Other important factors can strongly impact genetic diversity, including demography and structure, but also linked selection (Boitard et al. 2022; Buffalo 2021; Ellegren & Galtier 2016). All in all, Westbury and coll. (2022) present here an interesting study providing an additional step towards resolving and understanding the complex evolutionary history of the Delphinoidae, and shedding light on the importance of introgression during the diversification of these cetacean species. Prospective work improving upon the taxonomic sampling, with additional genomic data for each species, considered with dedicated approaches tailored at estimating species tree or network while accounting for ILS and introgression will be key for refining the picture depicted in this study. Down the road, altogether these studies will contribute to assessing the evolutionary significance of introgression on the diversification of Delphinoides, and more generally on the diversification of cetacean species, which still remain an open and exciting perspective. References Árnason Ú, Lammers F, Kumar V, Nilsson MA, Janke A (2018) Whole-genome sequencing of the blue whale and other rorquals finds signatures for introgressive gene flow. Science Advances 4, eaap9873. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aap9873 Bierne N, Bonhomme F, David P (2003) Habitat preference and the marine-speciation paradox. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 270, 1399-1406. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2003.2404 Blair C, Ané C (2020) Phylogenetic Trees and Networks Can Serve as Powerful and Complementary Approaches for Analysis of Genomic Data. Systematic Biology 69, 593-601. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syz056 Boitard S, Arredondo A, Chikhi L, Mazet O (2022) Heterogeneity in effective size across the genome: effects on the inverse instantaneous coalescence rate (IICR) and implications for demographic inference under linked selection. Genetics 220, iyac008. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyac008 Buffalo V (2021) Quantifying the relationship between genetic diversity and population size suggests natural selection cannot explain Lewontin's Paradox. e-Life 10, e67509. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.67509 Cahill JA, Soares AE, Green RE, Shapiro B (2016) Inferring species divergence times using pairwise sequential Markovian coalescent modelling and low-coverage genomic data. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 371, 20150138. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0138 Crossman CA, Taylor EB, Barrett‐Lennard LG (2016) Hybridization in the Cetacea: widespread occurrence and associated morphological, behavioral, and ecological factors. Ecology and Evolution 6, 1293-1303. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.1913 Dagilis AJ, Peede D, Coughlan JM, Jofre GI, D’Agostino ERR, Mavengere H, Tate AD, Matute DR (2021) 15 years of introgression studies: quantifying gene flow across Eukaryotes. biorXiv, 2021.1106.1115.448399. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.15.448399 Degnan JH, Rosenberg NA (2009) Gene tree discordance, phylogenetic inference and the multispecies coalescent. Trends Ecol Evol 24, 332-340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.01.009 Durand EY, Patterson N, Reich D, Slatkin M (2011) Testing for ancient admixture between closely related populations. Mol Biol Evol 28, 2239-2252. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msr048 Edelman NB, Frandsen PB, Miyagi M, Clavijo B, Davey J, Dikow RB, Garcia-Accinelli G, Van Belleghem SM, Patterson N, Neafsey DE, Challis R, Kumar S, Moreira GRP, Salazar C, Chouteau M, Counterman BA, Papa R, Blaxter M, Reed RD, Dasmahapatra KK, Kronforst M, Joron M, Jiggins CD, McMillan WO, Di Palma F, Blumberg AJ, Wakeley J, Jaffe D, Mallet J (2019) Genomic architecture and introgression shape a butterfly radiation. Science 366, 594-599. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw2090 Edelman NB, Mallet J (2021) Prevalence and Adaptive Impact of Introgression. Annual Review of Genetics 55, 265-283. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genet-021821-020805 Edwards CJ, Suchard MA, Lemey P, Welch JJ, Barnes I, Fulton TL, Barnett R, O'Connell TC, Coxon P, Monaghan N, Valdiosera CE, Lorenzen ED, Willerslev E, Baryshnikov GF, Rambaut A, Thomas MG, Bradley DG, Shapiro B (2011) Ancient hybridization and an Irish origin for the modern polar bear matriline. Curr Biol 21, 1251-1258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.058 Ellegren H, Galtier N (2016) Determinants of genetic diversity. Nat Rev Genet 17, 422-433. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.58 Flouri T, Jiao X, Rannala B, Yang Z (2018) Species Tree Inference with BPP Using Genomic Sequences and the Multispecies Coalescent. Mol Biol Evol 35, 2585-2593. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy147 Green RE, Krause J, Briggs AW, Maricic T, Stenzel U, Kircher M, Patterson N, Li H, Zhai W, Fritz MH, Hansen NF, Durand EY, Malaspinas AS, Jensen JD, Marques-Bonet T, Alkan C, Prufer K, Meyer M, Burbano HA, Good JM, Schultz R, Aximu-Petri A, Butthof A, Hober B, Hoffner B, Siegemund M, Weihmann A, Nusbaum C, Lander ES, Russ C, Novod N, Affourtit J, Egholm M, Verna C, Rudan P, Brajkovic D, Kucan Z, Gusic I, Doronichev VB, Golovanova LV, Lalueza-Fox C, de la Rasilla M, Fortea J, Rosas A, Schmitz RW, Johnson PLF, Eichler EE, Falush D, Birney E, Mullikin JC, Slatkin M, Nielsen R, Kelso J, Lachmann M, Reich D, Paabo S (2010) A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science 328, 710-722. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188021 Guo W, Sun D, Cao Y, Xiao L, Huang X, Ren W, Xu S, Yang G (2021) Extensive Interspecific Gene Flow Shaped Complex Evolutionary History and Underestimated Species Diversity in Rapidly Radiated Dolphins. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 29, 353-367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10914-021-09581-6 Hibbins MS, Hahn MW (2022) Phylogenomic approaches to detecting and characterizing introgression. Genetics 220, iyab173. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyab173 Jiao X, Flouri T, Rannala B, Yang Z (2020) The Impact of Cross-Species Gene Flow on Species Tree Estimation. Syst Biol 69, 830-847. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syaa001 Li H, Durbin R (2011) Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature 475, 493-496. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10231 Malinsky M, Matschiner M, Svardal H (2021) Dsuite - Fast D-statistics and related admixture evidence from VCF files. Mol Ecol Resour 21, 584-595. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13265 Malinsky M, Svardal H, Tyers AM, Miska EA, Genner MJ, Turner GF, Durbin R (2018) Whole-genome sequences of Malawi cichlids reveal multiple radiations interconnected by gene flow. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2, 1940-1955. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0717-x Mallet J, Besansky N, Hahn MW (2016) How reticulated are species? Bioessays 38, 140-149. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201500149 McGowen MR, Tsagkogeorga G, Alvarez-Carretero S, Dos Reis M, Struebig M, Deaville R, Jepson PD, Jarman S, Polanowski A, Morin PA, Rossiter SJ (2020) Phylogenomic Resolution of the Cetacean Tree of Life Using Target Sequence Capture. Syst Biol 69, 479-501. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syz068 Moura AE, Shreves K, Pilot M, Andrews KR, Moore DM, Kishida T, Möller L, Natoli A, Gaspari S, McGowen M, Chen I, Gray H, Gore M, Culloch RM, Kiani MS, Willson MS, Bulushi A, Collins T, Baldwin R, Willson A, Minton G, Ponnampalam L, Hoelzel AR (2020) Phylogenomics of the genus Tursiops and closely related Delphininae reveals extensive reticulation among lineages and provides inference about eco-evolutionary drivers. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 146,107047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2020.106756 Müller NF, Ogilvie HA, Zhang C, Fontaine MC, Amaya-Romero JE, Drummond AJ, Stadler T (in press) Joint inference of species histories and gene flow. Syst Biol. Pease JB, Hahn MW (2015) Detection and Polarization of Introgression in a Five-Taxon Phylogeny. Syst Biol 64, 651-662. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syv023 Rabier CE, Berry V, Stoltz M, Santos JD, Wang W, Glaszmann JC, Pardi F, Scornavacca C (2021) On the inference of complex phylogenetic networks by Markov Chain Monte-Carlo. PLoS Comput Biol 17, e1008380. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008380 Seehausen O (2004) Hybridization and adaptive radiation. Trends Ecol Evol 19, 198-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.01.003 Solís-Lemus C, Yang M, Ané C (2016) Inconsistency of Species Tree Methods under Gene Flow. Syst Biol 65, 843-851. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syw030 Thawornwattana Y, Dalquen D, Yang Z, Tamura K (2018) Coalescent Analysis of Phylogenomic Data Confidently Resolves the Species Relationships in the Anopheles gambiae Species Complex. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35, 2512-2527. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy158 Wang K, Mathieson I, O’Connell J, Schiffels S (2020) Tracking human population structure through time from whole genome sequences. PLOS Genetics 16, e1008552. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008552 Westbury MV, Cabrera AA, Rey-Iglesia A, Cahsan BD, Duchêne DA, Hartmann S, Lorenzen ED (2022) A genomic assessment of the marine-speciation paradox within the toothed whale superfamily Delphinoidea. bioRxiv, 2020.10.23.352286, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.23.352286 Westbury MV, Petersen B, Lorenzen ED (2019) Genomic analyses reveal an absence of contemporary introgressive admixture between fin whales and blue whales, despite known hybrids. PLoS ONE 14, e0222004. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222004 Yang Z (2015) The BPP program for species tree estimation and species delimitation. Current Zoology 61, 854-865. https://doi.org/10.1093/czoolo/61.5.854 Zhang C, Rabiee M, Sayyari E, Mirarab S (2018) ASTRAL-III: polynomial time species tree reconstruction from partially resolved gene trees. BMC Bioinformatics 19, 153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-018-2129-y | A genomic assessment of the marine-speciation paradox within the toothed whale superfamily Delphinoidea | Michael V Westbury, Andrea A Cabrera, Alba Rey-Iglesia, Binia De Cahsan, David A. Duchêne, Stefanie Hartmann, Eline D Lorenzen | <p>The importance of post-divergence gene flow in speciation has been documented across a range of taxa in recent years, and may have been especially widespread in highly mobile, wide-ranging marine species, such as cetaceans. Here, we studied ind... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Hybridization / Introgression, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Speciation | Michael C. Fontaine | 2020-10-25 08:55:50 | View | |

29 Sep 2017

Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of the South American continentMichael D. Pirie, Paul J. M. Maas, Rutger A. Wilschut, Heleen Melchers-Sharrott & Lars W. Chatrou 10.1101/141127Unravelling the history of Neotropical plant diversificationRecommended by Hervé Sauquet based on reviews by Thomas Couvreur and Hervé SauquetSouth American rainforests, particularly the Tropical Andes, have been recognized as the hottest spot of plant biodiversity on Earth, while facing unprecedented threats from human impact [1,2]. Considerable research efforts have recently focused on unravelling the complex geological, bioclimatic, and biogeographic history of the region [3,4]. While many studies have addressed the question of Neotropical plant diversification using parametric methods to reconstruct ancestral areas and patterns of dispersal, Pirie et al. [5] take a distinct, complementary approach. Based on a new, near-complete molecular phylogeny of two Neotropical genera of the flowering plant family Annonaceae, the authors modelled the ecological niche of each species and reconstructed the history of niche differentiation across the region. The main conclusion is that, despite similar current distributions and close phylogenetic distance, the two genera experienced rather distinct processes of diversification, responding differently to the major geological events marking the history of the region in the last 20 million years (Andean uplift, drainage of Lake Pebas, and closure of the Panama Isthmus). As a researcher who has not personally worked on Neotropical biogeography, I found this paper captivating and especially enjoyed very much reading the Introduction, which sets out the questions very clearly. The strength of this paper is the near-complete diversity of species the authors were able to sample in each clade and the high-quality data compiled for the niche models. I would recommend this paper as a nice example of a phylogenetic study aimed at unravelling the detailed history of Neotropical plant diversification. While large, synthetic meta-analyses of many clades should continue to seek general patterns [4,6], careful studies restricted on smaller, but well controlled and sampled datasets such as this one are essential to really understand tropical plant diversification in all its complexity. References [1] Antonelli A, and Sanmartín I. 2011. Why are there so many plant species in the Neotropics? Taxon 60, 403–414. [2] Mittermeier RA, Robles-Gil P, Hoffmann M, Pilgrim JD, Brooks TB, Mittermeier CG, Lamoreux JL and Fonseca GAB. 2004. Hotspots revisited: Earths biologically richest and most endangered ecoregions. CEMEX, Mexico City, Mexico 390pp [3] Antonelli A, Nylander JAA, Persson C and Sanmartín I. 2009. Tracing the impact of the Andean uplift on Neotropical plant evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA 106, 9749–9754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811421106 [4] Hoorn C, Wesselingh FP, ter Steege H, Bermudez MA, Mora A, Sevink J, Sanmartín I, Sanchez-Meseguer A, Anderson CL, Figueiredo JP, Jaramillo C, Riff D, Negri FR, Hooghiemstra H, Lundberg J, Stadler T, Särkinen T and Antonelli A. 2010. Amazonia through time: Andean uplift, climate change, landscape evolution, and biodiversity. Science 330, 927–931. doi: 10.1126/science.1194585 [5] Pirie MD, Maas PJM, Wilschut R, Melchers-Sharrott H and Chatrou L. 2017. Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of the South American continent. bioRxiv, 141127, ver. 3 of 28th Sept 2017. doi: 10.1101/141127 [6] Bacon CD, Silvestro D, Jaramillo C, Tilston Smith B, Chakrabartye P and Antonelli A. 2015. Biological evidence supports an early and complex emergence of the Isthmus of Panama. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA 112, 6110–6115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423853112 | Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of the South American continent | Michael D. Pirie, Paul J. M. Maas, Rutger A. Wilschut, Heleen Melchers-Sharrott & Lars W. Chatrou | Much of the immense present day biological diversity of Neotropical rainforests originated from the Miocene onwards, a period of geological and ecological upheaval in South America. We assess the impact of the Andean orogeny, drainage of lake Peba... |  | Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Hervé Sauquet | Hervé Sauquet, Thomas Couvreur | 2017-06-03 21:25:48 | View |

11 May 2021

Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factorsAlexis Bénard, Hélène Henri, Camille Noûs, Fabrice Vavre, Natacha Kremer https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.29.402545Drift rather than host or parasite control can explain within-host Wolbachia growthRecommended by Alison Duncan and Michael Hochberg based on reviews by Simon Fellous and 1 anonymous reviewerWithin-host parasite density is tightly linked to parasite fitness often determining both transmission success and virulence (parasite-induced harm to the host) (Alizon et al., 2009, Anderson & May, 1982). Parasite density may thus be controlled by selection balancing these conflicting pressures. Actual within-host density regulation may be under host or parasite control, or due to other environmental factors (Wale et al., 2019, Vale et al., 2011, Chrostek et al., 2013). Vertically transmitted parasites may also be more vulnerable to drift associated with bottlenecks between generations, which may also determine within-host population size (Mathe-Hubert et al., 2019, Mira & Moran, 2002). Bénard et al. (2021) use 3 experiments to disentangle the role of drift versus host factors in the control of within-host Wolbachia growth in Drosophila melanogaster. They use the wMelPop Wolbachia strain in which virulence (fly longevity) and within-host growth correlate positively with copy number in the genomic region Octomom (Chrostek et al., 2013, Chrostek & Teixeira, 2015). Octomom copy number can be used as a marker for different genetic lineages within the wMelPop strain. In a first experiment, they introgressed and backcrossed this Wolbachia strain into 6 different host genetic backgrounds and show striking differences in within-host symbiont densities which correlate positively with Octomom copy number. This is consistent with host genotype selecting different Wolbachia strains, but also with bottlenecks and drift between generations. To distinguish between these possibilities, they perform 2 further experiments. A second experiment repeated experiment 1, but this time introgression was into 3 independent lines of the Bolivia and USA Drosophila populations; those that, respectively, exhibited the lowest and highest Wolbachia density and Octomom copy number. In this experiment, growth and Octomom copy number were measured across the 3 lines, for each population, after 1, 13 and 25 generations. Although there were little differences between replicates at generation 1, there were differences at generations 13 and 25 among the replicates of both the Bolivia and USA lines. These results are indicative of parasite control, or drift being responsible for within-host growth rather than host factors. A third experiment tested whether Wolbachia density and copy number were under host or parasite control. This was done, again using the USA and Bolivia lines, but this time those from the first experiment, several generations following the initial introgression and backcrossing. The newly introgressed lines were again followed for 25 generations. At generation 1, Wolbachia phenotypes resembled those of the donor parasite population and not the recipient host population indicating a possible maternal effect, but a lack of host control over the parasite. Furthermore, Wolbachia densities and Octomom number differed among replicate lines through time for Bolivia populations and from the donor parasite lines for both populations. These differences among replicate lines that share both host and parasite origins suggest that drift and/or maternal effects are responsible for within-host Wolbachia density and Octomom number. These findings indicate that drift appears to play a role in shaping Wolbachia evolution in this system. Nevertheless, completely ruling out the role of the host or parasite in controlling densities will require further study. The findings of Bénard and coworkers (2021) should stimulate future work on the contribution of drift to the evolution of vertically transmitted parasites. References Alizon S, Hurford A, Mideo N, Baalen MV (2009) Virulence evolution and the trade-off hypothesis: history, current state of affairs and the future. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22, 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01658.x Anderson RM, May RM (1982) Coevolution of hosts and parasites. Parasitology, 85, 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000055360 Bénard A, Henri H, Noûs C, Vavre F, Kremer N (2021) Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factors. bioRxiv, 2020.11.29.402545, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.29.402545 Chrostek E, Marialva MSP, Esteves SS, Weinert LA, Martinez J, Jiggins FM, Teixeira L (2013) Wolbachia Variants Induce Differential Protection to Viruses in Drosophila melanogaster: A Phenotypic and Phylogenomic Analysis. PLOS Genetics, 9, e1003896. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003896 Chrostek E, Teixeira L (2015) Mutualism Breakdown by Amplification of Wolbachia Genes. PLOS Biology, 13, e1002065. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002065 Mathé‐Hubert H, Kaech H, Hertaeg C, Jaenike J, Vorburger C (2019) Nonrandom associations of maternally transmitted symbionts in insects: The roles of drift versus biased cotransmission and selection. Molecular Ecology, 28, 5330–5346. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15206 Mira A, Moran NA (2002) Estimating Population Size and Transmission Bottlenecks in Maternally Transmitted Endosymbiotic Bacteria. Microbial Ecology, 44, 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-002-0012-9 Vale PF, Wilson AJ, Best A, Boots M, Little TJ (2011) Epidemiological, Evolutionary, and Coevolutionary Implications of Context-Dependent Parasitism. The American Naturalist, 177, 510–521. https://doi.org/10.1086/659002 Wale N, Jones MJ, Sim DG, Read AF, King AA (2019) The contribution of host cell-directed vs. parasite-directed immunity to the disease and dynamics of malaria infections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116, 22386–22392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908147116

| Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factors | Alexis Bénard, Hélène Henri, Camille Noûs, Fabrice Vavre, Natacha Kremer | <p style="text-align: justify;">Symbiosis is a continuum of long-term interactions ranging from mutualism to parasitism, according to the balance between costs and benefits for the protagonists. The density of endosymbionts is, in both cases, a ke... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Genetic conflicts, Species interactions | Alison Duncan | 2020-12-01 16:28:14 | View | |

26 Oct 2021

Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North AfricaOlvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tournant L., Gazel F., Mody K., Khachtib Y., Roman A., Ursu T.M., Zakharov I.A., Belcram H., Harry M., Roth M., Simon J.C., Oram S., Ricard J.M., Agnello A., Beers E. H., Engelman J., Balti I., Salhi-Hannachi A., Zhang H., Tu H., Mottet C., Barrès B., Degra... https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.11.421644The evolutionary puzzle of the host-parasite-endosymbiont Russian doll for apples and aphidsRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewerEach individual multicellular organism, each of our bodies, is a small universe. Every living surface -skin, cuticle, bark, mucosa- is the home place to milliards of bacteria, fungi and viruses. They constitute our microbiota. Some of them are essential for certain organisms. Other could not live without their hosts. For many species, the relationship between host and microbiota is so close that their histories are inseparable. The recognition of this biological inextricability has led to the notion of holobiont as the organism ensemble of host and microbiota. When individuals of a particular animal or plant species expand their geographical range, it is the holobiont that expands. And these processes of migration, expansion and colonization are often accompanied by evolutionary and ecological innovations in the interspecies relationships, at the macroscopic level (e.g. novel predator-prey or host-parasite interactions) and at the microscopic level (e.g. changes in the microbiota composition). From the human point of view, these novel interactions can be economically disastrous if they involve and threaten important crop or cattle species. And this is especially worrying in the present context of genetic standardization and intensification for mass-production on the one hand, and of climate change on the other. With this perspective, the international team led by Amandine Cornille presents a study aiming at understanding the evolutionary history of the rosy apple aphid Dysaphis plantaginea Passerini, a major pest of the cultivated apple tree Malus domestica Borkh (1). The apple tree was probably domesticated in Central Asia, and later disseminated by humans over the world in different waves, and it was probably introduced in Europe by the Greeks. It is however unclear when and where D. plantaginea started parasitizing the cultivated apple tree. The ancestral D. plantaginea could have already infected the wild ancestor of current cultivated apple trees, but the aphid is not common in Central Asia. Alternatively, it may have gained access only later to the plant, possibly via a host jump, from Pyrus to Malus that may have occurred in Asia Minor or in the Caucasus. In the present preprint, Olvera-Vázquez and coworkers have analysed over 650 D. plantaginea colonies from 52 orchards in 13 countries, in Western, Central and Eastern Europe as well as in Morocco and the USA. The authors have analysed the genetic diversity in the sampled aphids, and have characterized as well the composition of the associated endosymbiont bacteria. The analyses detect substantial recent admixture, but allow to identify aphid subpopulations slightly but significantly differentiated and isolated by distance, especially those in Morocco and the USA, as well as to determine the presence of significant gene flow. This process of colonization associated to gene flow is most likely indirectly driven by human interactions. Very interestingly, the data show that this genetic diversity in the aphids is not reflected by a corresponding diversity in the associated microbiota, largely dominated by a few Buchnera aphidicola variants. In order to determine polarity in the evolutionary history of the aphid-tree association, the authors have applied approximate Bayesian computing and machine learning approaches. Albeit promising, the results are not sufficiently robust to assess directionality nor to confidently assess the origin of the crop pest. Despite the large effort here communicated, the authors point to the lack of sufficient data (in terms of aphid isolates), especially originating from Central Asia. Such increased sampling will need to be implemented in the future in order to elucidate not only the origin and the demographic history of the interaction between the cultivated apple tree and the rosy apple aphid. This knowledge is needed to understand how this crop pest struggles with the different seasonal and geographical selection pressures while maintaining high genetic diversity, conspicuous gene flow, differentiated populations and low endosymbiontic diversity. References

| Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North Africa | Olvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tour... | <p style="text-align: justify;">With frequent host shifts involving the colonization of new hosts across large geographical ranges, crop pests are good models for examining the mechanisms of rapid colonization. The microbial partners of pest insec... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics, Species interactions | Ignacio Bravo | 2020-12-11 19:22:54 | View | |

06 Jul 2018

Variation in competitive ability with mating system, ploidy and range expansion in four Capsella speciesXuyue Yang, Martin Lascoux and Sylvain Glémin https://doi.org/10.1101/214866When ecology meets genetics: Towards an integrated understanding of mating system transitions and diversityRecommended by Sylvain Billiard and Henrique Teotonio based on reviews by Yaniv Brandvain, Henrique Teotonio and 1 anonymous reviewerIn the 19th century, C. Darwin and F. Delpino engaged in a debate about the success of species with different reproduction modes, with the later favouring the idea that monoecious plants capable of autonomous selfing could spread more easily than dioecious plants (or self-incompatible hermaphroditic plants) if cross-pollination opportunities were limited [1]. Since then, debate has never faded about how natural selection is responsible for transitions to selfing and can explain the diversity and distribution of reproduction modes we observe in the natural world [2, 3]. References [1] Darwin, C. R. (1876). The effects of cross and self fertilization in the vegetable kingdom. London: Murray.

[2] Stebbins, G. L. (1957). Self fertilization and population variability in the higher plants. The American Naturalist, 91, 337-354. doi: 10.1086/281999 | Variation in competitive ability with mating system, ploidy and range expansion in four Capsella species | Xuyue Yang, Martin Lascoux and Sylvain Glémin | <p>Self-fertilization is often associated with ecological traits corresponding to the ruderal strategy in Grime’s Competitive-Stress-tolerant-Ruderal (CSR) classification of ecological strategies. Consequently, selfers are expected to be less comp... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Sylvain Billiard | 2017-11-06 19:54:52 | View | |

14 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasitePalmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS 10.1111/jeb.13002The medicinal value of phytochemicals is hindered by pathogen evolution of resistanceRecommended by Alison Duncan and Sara MagalhaesAs plants cannot run from their enemies, natural selection has favoured the evolution of diverse chemical compounds (phytochemicals) to protect them against herbivores and pathogens. This provides an opportunity for plant feeders to exploit these compounds to combat their own enemies. Indeed, it is widely known that herbivores use such compounds as protection against predators [1]. Recently, this reasoning has been extended to pathogens, and elegant studies have shown that some herbivores feed on phytochemical-containing plants reducing both parasite abundance within hosts [2] and their virulence [3]. References [1] Duffey SS. 1980. Sequestration of plant natural products by insects. Annual Review of Entomology 25: 447-477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.25.010180.002311 [2] Richardson LL et al. 2015. Secondary metabolites in floral nectar reduce parasite infections in bumblebees. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 282: 20142471. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2471 [3] Lefèvre T et al. 2010. Evidence for trans-generational medication in nature. Ecology Letters 13: 1485-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01537.x [4] Palmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS. 2017. Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasite. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 30: 300-312. doi: 10.1111/jeb.13002 [5] Müller CB, Schmid-Hempel P. 1993. Exploitation of cold temperature as defence against parasitoids in bumblebees. Nature 363: 65-67. doi: 10.1038/363065a0 [6] Potts SG et al. 2010. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 25: 345-353. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007 | Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasite | Palmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS | Repeated exposure to inhibitory compounds can drive the evolution of resistance, which weakens chemical defence against antagonists. Floral phytochemicals in nectar and pollen have antimicrobial properties that can ameliorate infection in pollinat... |  | Evolutionary Ecology | Alison Duncan | 2016-12-14 16:47:14 | View | |

29 Nov 2023

Does sociality affect evolutionary speed?Lluís Socias-Martínez, Louise Rachel Peckre https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10086186On the evolutionary implications of being a social animalRecommended by Michael D Greenfield based on reviews by Rafael Lucas Rodriguez and 1 anonymous reviewerWhat does it mean to be highly social? Considering the so-called four ‘pinnacles’ of animal society (Wilson, 1975) – humans, cooperative breeding as found in some non-human mammals and birds, the social insects, and colonial marine invertebrates – having inter-individual relations extending beyond the sexual pair and the parent-offspring interaction is foremost. In many cases being social implies a high local population density, interaction with the same group of individuals over an extended time period, and an overlapping of generations. Additional features of social species may be a wide geographical range, perhaps associated with ecological and behavioral plasticity, the latter often facilitated by cultural transmission of traditions. Narrowing our perspective to the domain of PCI Evolutionary Biology, we might continue our question by asking whether being social predisposes one to a special evolutionary path toward the future. Do social species evolve faster (or slower) than their more solitary relatives such that over time they are more unlike (or similar to) those relatives (anagenesis)? And are evolutionary changes in social species more or less likely to be accompanied by lineage splitting (cladogenesis) and ultimately speciation? The latter question is parallel to one first posed over 40 years ago (West-Eberhard, 1979; Lande, 1981) for sexually selected traits: Do strong mating preferences and conspicuous courtship signals generate speciation via the Fisherian process or ecological divergence? An extensive survey of birds had found little supporting evidence (Price, 1998), but a recent one that focused on plumage complexity in tanagers did reveal a relationship, albeit a weak one (Price-Waldman et al., 2020). Because sexual selection has been viewed as a part of the broader process of social selection (West-Eberhard, 1979), it is thus fitting to extend our surveys to the evolutionary implications of being social. Unlike the inquiry for a sexual selection - evolutionary change connection, a social behavior counterpart has remained relatively untreated. Diverse logistical problems might account for this oversight. What objective proxies can be used for social behavior, and for the rate of evolutionary change within a lineage? How many empirical studies have generated data from which appropriate proxies could be extracted? More intractable is the conundrum arising from the connectedness between socially- and sexually-selected traits. For example, the elevated population density found in highly social species can greatly increase the mating advantage enjoyed by an attractive male. If anagenesis is detected, did it result from social behavior or sexual selection? And if social behavior leads to a group structure in which male-male competition is reduced, would a modest rate of evolutionary change be support for the sexual selection - evolutionary speed connection or evidence opposing the sociality - evolution one? Against the above odds, several biologists have begun to explore the notion that social behavior just might favor evolutionary speed in either anagenesis or cladogenesis. In a recent analysis relying on the comparative method, Lluís Socias-Martínez and Louise Rachel Peckre (2023) combed the scientific literature archives and identified those studies with specific data on the relationships between sexual selection or social behavior and evolutionary change, either anagenesis or cladogenesis. The authors were careful to employ fairly conservative criteria for including studies, and the number eventually retained was small. Nonetheless, some patterns emerge: Many more studies report anagenesis than cladogenesis, and many more report correlations with sexually-selected traits than with non-sexual social behavior ones. And, no study indicates a potential effect of social behavior on cladogenesis. Is this latter observation authentic or an artifact of a paucity of data? There are some a priori reasons why cladogenesis may seldom arise. Whereas highly social behavior could lead to fission encompassing mutually isolated population clusters within a species, social behavior may also engender counterbalancing plasticity that allows and even promotes inter-cluster migration and fusion. And briefly – and non-systematically, as the rate of lineage splitting would need to be measured – looking at one of the pinnacles of animal social behavior, the social insects, there is little indication that diversification has been accelerated. There are fewer than 3000 described species of termites, only ca. 16,000 ants, and the vast majority of bees and wasps are solitary. Lluís Socias-Martínez and Louise Rachel Peckre provide us with a very detailed discussion of these and a myriad of other complications. I end with a common refrain, we need more consideration of the authors’ interesting question, and much more data and analysis. One can thank Socias-Martínez and Peckre for pointing us in that direction. References Lande, R. (1981). Models of speciation by sexual selection on polygenic traits. Proc. Natn. Acad. Sci. USA 78, 3721-3725. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.78.6.3721 Price, T. (1998). Sexual selection and natural selection in bird speciation. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. B, 353, 251-260. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1998.0207 Price‐Waldman, R. M., Shultz, A. J., & Burns, K. J. (2020). Speciation rates are correlated with changes in plumage color complexity in the largest family of songbirds. Evolution, 74(6), 1155–1169. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13982 Socias-Martínez and Peckre. (2023). Does sociality affect evolutionary speed? Zenodo, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10086186 West-Eberhard, M. J. (1979). Sexual selection, social competition, and evolution. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 123(4), 222–234. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2828804 Wilson, E. O. (1975). Sociobiology. The New Synthesis. Cambridge, Mass., The Belknap Press of Harvard University | Does sociality affect evolutionary speed? | Lluís Socias-Martínez, Louise Rachel Peckre | <p>An overlooked source of variation in evolvability resides in the social lives of animals. In trying to foster research in this direction, we offer a critical review of previous work on the link between evolutionary speed and sociality. A first ... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Sexual Selection, Speciation | Michael D Greenfield | 2023-03-03 00:10:49 | View | |

10 Jan 2019

Genomic data provides new insights on the demographic history and the extent of recent material transfers in Norway spruceJun Chen, Lili Li, Pascal Milesi, Gunnar Jansson, Mats Berlin, Bo Karlsson, Jelena Aleksic, Giovanni G Vendramin, Martin Lascoux https://doi.org/10.1101/402016Disentangling the recent and ancient demographic history of European spruce speciesRecommended by Jason Holliday based on reviews by 1 anonymous reviewerGenetic diversity in temperate and boreal forests tree species has been strongly affected by late Pleistocene climate oscillations [2,3,5], but also by anthropogenic forces. Particularly in Europe, where a long history of human intervention has re-distributed species and populations, it can be difficult to know if a given forest arose through natural regeneration and gene flow or through some combination of natural and human-mediated processes. This uncertainty can confound inferences of the causes and consequences of standing genetic variation, which may impact our interpretation of demographic events that shaped species before humans became dominant on the landscape. In their paper entitled "Genomic data provides new insights on the demographic history and the extent of recent material transfers in Norway spruce", Chen et al. [1] used a genome-wide dataset of 400k SNPs to infer the demographic history of Picea abies (Norway spruce), the most widespread and abundant spruce species in Europe, and to understand its evolutionary relationship with two other spruces (Picea obovata [Siberian spruce] and P. omorika [Serbian spruce]). Three major Norway spruce clusters were identified, corresponding to central Europe, Russia and the Baltics, and Scandinavia, which agrees with previous studies. The density of the SNP data in the present paper enabled inference of previously uncharacterized admixture between these groups, which corresponds to the timing of postglacial recolonization following the last glacial maximum (LGM). This suggests that multiple migration routes gave rise to the extant distribution of the species, and may explain why Chen et al.'s estimates of divergence times among these major Norway spruce groups were older (15mya) than those of previous studies (5-6mya) – those previous studies may have unknowingly included admixed material [4]. Treemix analysis also revealed extensive admixture between Norway and Siberian spruce over the last ~100k years, while the geographically-restricted Serbian spruce was both isolated from introgression and had a dramatically smaller effective population size (Ne) than either of the other two species. This small Ne resulted from a bottleneck associated with the onset of the iron age ~3000 years ago, which suggests that anthropogenic depletion of forest resources has severely impacted this species. Finally, ancestry of Norway spruce samples collected in Sweden and Denmark suggest their recent transfer from more southern areas of the species range. This northward movement of genotypes likely occurred because the trees performed well relative to local provenances, which is a common observation when trees from the south are planted in more northern locations (although at the potential cost of frost damage due to inappropriate phenology). While not the reason for the transfer, the incorporation of southern seed sources into the Swedish breeding and reforestation program may lead to more resilient forests under climate change. Taken together, the data and analysis presented in this paper allowed inference of the intra- and interspecific demographic histories of a tree species group at a very high resolution, and suggest caveats regarding sampling and interpretation of data from areas with a long history of occupancy by humans. References [1] Chen, J., Milesi, P., Jansson, G., Berlin, M., Karlsson, B., Aleksić, J. M., Vendramin, G. G., Lascoux, M. (2018). Genomic data provides new insights on the demographic history and the extent of recent material transfers in Norway spruce. BioRxiv, 402016. ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/402016 | Genomic data provides new insights on the demographic history and the extent of recent material transfers in Norway spruce | Jun Chen, Lili Li, Pascal Milesi, Gunnar Jansson, Mats Berlin, Bo Karlsson, Jelena Aleksic, Giovanni G Vendramin, Martin Lascoux | <p>Primeval forests are today exceedingly rare in Europe and transfer of forest reproductive material for afforestation and improvement have been very common, especially over the last two centuries. This can be a serious impediment when inferring ... | Evolutionary Applications, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics | Jason Holliday | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2018-08-29 08:33:15 | View | |

23 Jan 2023

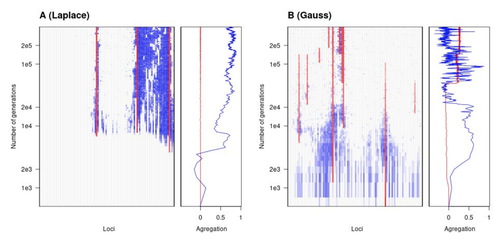

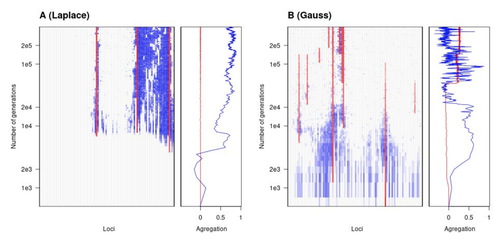

The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a clineFabien Laroche, Thomas Lenormand https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.30.498280Environmental and fitness landscapes matter for the genetic basis of local adaptationRecommended by Charles Mullon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Natural landscapes are often composite, with spatial variation in environmental factors being the norm rather than exception. Adaptation to such variation is a major driver of diversity at all levels of biological organization, from genes to phenotypes, species and ultimately ecosystems. While natural selection favours traits that show a better fit to local conditions, the genomic response to such selection is not necessarily straightforward. This is because many quantitative traits are complex and the product of many loci, each with a small to moderate phenotypic contribution. Adapting to environmental challenges that occur in narrow ranges may thus prove difficult as each individual locus is easily swamped by alleles favoured across the rest of the population range. To better understand whether and how evolution overcomes such a hurdle, Laroche and Lenormand [1] combine quantitative genetics and population genetic modelling to track genomic changes that underpin a trait whose fitness optimum differs between a certain spatial range, referred to as a “pocket”, and the rest of the habitat. As it turns out from their analysis, one critical and probably underappreciated factor in determining the type of genetic architecture that evolves is how fitness declines away from phenotypic optima. One classical and popular model of fitness landscape that relates trait value to reproductive success is Gaussian, whereby small trait variations away from the optimum result in even smaller variations in fitness. This facilitates local adaptation via the invasion of alleles of small effects as carriers inside the pocket show a better fit while those outside the pocket only suffer a weak fitness cost. By contrast, when the fitness landscape is more peaked around the optimum, for instance where the decline is linear, adaptation through weak effect alleles is less likely, requiring larger pockets that are less easily swamped by alleles selected in the rest of the range. In addition to mathematically investigating the initial emergence of local adaptation, Laroche and Lenormand use computer simulations to look at its long-term maintenance. In principle, selection should favour a genetic architecture that consolidates the phenotype and increases its heritability, for instance by grouping several alleles of large effects close to one another on a chromosome to avoid being broken down by meiotic recombination. Whether or not this occurs also depends on the fitness landscape. When the landscape is Gaussian, the genetic architecture of the trait eventually consists of tightly linked alleles of large effects. The replacement of small effects by large effects loci is here again promoted by the slow fitness decline around the optimum. This is because any shift in architecture in an adapted population requires initially crossing a fitness valley. With a Gaussian landscape, this valley is shallow enough to be crossed, facilitated by a bit of genetic drift. By contrast, when fitness declines linearly around the optimum, genetic architecture is much less evolutionarily labile as any architecture change initially entails a fitness cost that is too high to bear. Overall, Laroche and Lenormand provide a careful and thought-provoking analysis of a classical problem in population genetics. In addition to questioning some longstanding modelling assumptions, their results may help understand why differentiated populations are sometimes characterized by “genomic islands” of divergence, and sometimes not. References [1] Laroche F, Lenormand T (2022) The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a cline. bioRxiv, 2022.06.30.498280, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.30.498280 | The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a cline | Fabien Laroche, Thomas Lenormand | <p>Local adaptation is pervasive. It occurs whenever selection favors different phenotypes in different environments, provided that there is genetic variation for the corresponding traits and that the effect of selection is greater than the effect... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics | Charles Mullon | 2022-07-07 08:46:47 | View | |

26 Sep 2017

Lacking conservation genomics in the giant Galápagos tortoiseEtienne Loire, Nicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/101980A genomic perspective is needed for the re-evaluation of species boundaries, evolutionary trajectories and conservation strategies for the Galápagos giant tortoisesRecommended by Michael C. Fontaine based on reviews by 4 anonymous reviewersGenome-wide data obtained from even a small number of individuals can provide unprecedented levels of detail about the evolutionary history of populations and species [1], determinants of genetic diversity [2], species boundaries and the process of speciation itself [3]. Loire and Galtier [4] present a clear example, using the emblematic Galápagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis nigra), of how multi-species comparative population genomic approaches can provide valuable insights about population structure and species delimitation even when sample sizes are limited but the number of loci is large and distributed across the genome. Galápagos giant tortoises are endemic to the Galápagos Islands and are currently recognized as an endangered, multi-species complex including both extant and extinct taxa. Taxonomic definitions are based on morphology, geographic isolation and population genetic evidence based on short DNA sequences of the mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) and/or a dozen or so nuclear microsatellite loci [5-8]. The species complex enjoys maximal protection. Population recoveries have been quite successful and spectacular conservation programs based on mitochondrial genes and microsatellites are ongoing. This includes for example individual translocations, breeding program, “hybrid” sterilization or removal, and resurrection of extinct lineages). In 2013, Loire et al. [9] provided the first population genomic analyses based on genome scale data (~1000 coding loci derived from blood-transcriptomes) from five individuals, encompassing three putative “species”: Chelonnoidis becki, C. porteri and C. vandenburghi. Their results raised doubts about the validity/accuracy of the currently accepted designations of “genetic distinctiveness”. However, the implications for conservation and management have remained unnoticed. In 2017, Loire and Galtier [4] have re-appraised this issue using an original multi-species comparative population genomic analysis of their previous data set [9]. Based on a comparison of 53 animal species, they show that both the level of genome-wide neutral diversity (πS) and level of population structure estimated using the inbreeding coefficient (F) are much lower than would be expected from a sample covering multiple species. The observed values are more comparable to those typically reported at the “among population” level within a single species such as human (Homo sapiens). The authors go to great length to assess the sensitivity of their method to detect population structure (or lack thereof) and show that their results are robust to potential issues, such as contamination and sequencing errors that can occur with Next Generation Sequencing techniques; and biases related to the small sample size and sub-sampling of individuals. They conclude that published mtDNA and microsatellite-based assessment of population structure and species designations may be biased towards over-splitting. This manuscript is a very good read as it shows the potential of the now relatively affordable genome-wide data for helping to both resolve and clarify population and species boundaries, illuminate demographic trends, evolutionary trajectories of isolated groups, patterns of connectivity among them, and test for evidence of local adaptation and even reproductive isolation. The comprehensive information provided by genome-wide data can critically inform and assist the development of the best strategies to preserve endangered populations and species. Loire and Galtier [4] make a strong case for applying genomic data to the Galápagos giant tortoises, which is likely to redirect conservation efforts more effectively and at lower cost. The case of the Galápagos giant tortoises is certainly a very emblematic example, which will find an echo in many other endangered species conservation programs. References [1] Li H and Durbin R. 2011. Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature, 475: 493–496. doi: 10.1038/nature10231 [2] Romiguier J, Gayral P, Ballenghien M, Bernard A, Cahais V, Chenuil A, Chiari Y, Dernat R, Duret L, Faivre N, Loire E, Lourenco JM, Nabholz B, Roux C, Tsagkogeorga G, Weber AA-T, Weinert LA, Belkhir K, Bierne N, Glémin S and Galtier N. 2014. Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature, 515: 261–263. doi: 10.1038/nature13685 [3] Roux C, Fraïsse C, Romiguier J, Anciaux Y, Galtier N and Bierne N. 2016. Shedding light on the grey zone of speciation along a continuum of genomic divergence. PLoS Biology, 14: e2000234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2000234 [4] Loire E and Galtier N. 2017. Lacking conservation genomics in the giant Galápagos tortoise. bioRxiv 101980, ver. 4 of September 26, 2017. doi: 10.1101/101980 [5] Beheregaray LB, Ciofi C, Caccone A, Gibbs JP and Powell JR. 2003. Genetic divergence, phylogeography and conservation units of giant tortoises from Santa Cruz and Pinzón, Galápagos Islands. Conservation Genetics, 4: 31–46. doi: 10.1023/A:1021864214375 [6] Ciofi C, Milinkovitch MC, Gibbs JP, Caccone A and Powell JR. 2002. Microsatellite analysis of genetic divergence among populations of giant Galápagos tortoises. Molecular Ecology, 11: 2265–2283. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01617.x [7] Garrick RC, Kajdacsi B, Russello MA, Benavides E, Hyseni C, Gibbs JP, Tapia W and Caccone A. 2015. Naturally rare versus newly rare: demographic inferences on two timescales inform conservation of Galápagos giant tortoises. Ecology and Evolution, 5: 676–694. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1388 [8] Poulakakis N, Edwards DL, Chiari Y, Garrick RC, Russello MA, Benavides E, Watkins-Colwell GJ, Glaberman S, Tapia W, Gibbs JP, Cayot LJ and Caccone A. 2015. Description of a new Galápagos giant tortoise species (Chelonoidis; Testudines: Testudinidae) from Cerro Fatal on Santa Cruz island. PLoS ONE, 10: e0138779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138779 [9] Loire E, Chiari Y, Bernard A, Cahais V, Romiguier J, Nabholz B, Lourenço JM and Galtier N. 2013. Population genomics of the endangered giant Galápagos tortoise. Genome Biology, 14: R136. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-12-r136 | Lacking conservation genomics in the giant Galápagos tortoise | Etienne Loire, Nicolas Galtier | <p>Conservation policy in the giant Galápagos tortoise, an iconic endangered animal, has been assisted by genetic markers for ~15 years: a dozen loci have been used to delineate thirteen (sub)species, between which hybridization is prevented. Here... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation, Systematics / Taxonomy | Michael C. Fontaine | 2017-01-21 15:34:00 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer