Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▼ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

22 May 2023

Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweepsKevin Korfmann, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.26.489499New insights into the dynamics of selective sweeps in seed-banked speciesRecommended by Renaud Vitalis based on reviews by Guillaume Achaz, Jere Koskela, William Shoemaker and Simon Boitard based on reviews by Guillaume Achaz, Jere Koskela, William Shoemaker and Simon Boitard

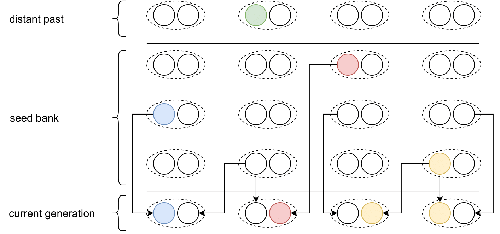

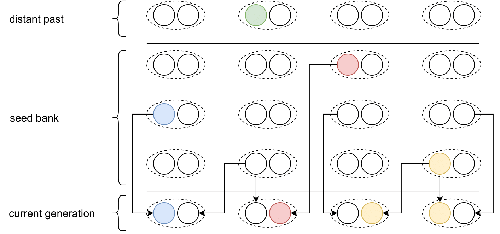

Many organisms across the Tree of life have the ability to produce seeds, eggs, cysts, or spores, that can remain dormant for several generations before hatching. This widespread adaptive trait in bacteria, fungi, plants and animals, has a significant impact on the ecology, population dynamics and population genetics of species that express it (Evans and Dennehy 2005). In population genetics, and despite the recognition of its evolutionary importance in many empirical studies, few theoretical models have been developed to characterize the evolutionary consequences of this trait on the level and distribution of neutral genetic diversity (see, e.g., Kaj et al. 2001; Vitalis et al. 2004), and also on the dynamics of selected alleles (see, e.g., Živković and Tellier 2018). However, due to the complexity of the interactions between evolutionary forces in the presence of dormancy, the fate of selected mutations in their genomic environment is not yet fully understood, even from the most recently developed models. In a comprehensive article, Korfmann et al. (2023) aim to fill this gap by investigating the effect of germ banking on the probability of (and time to) fixation of beneficial mutations, as well as on the shape of the selective sweep in their vicinity. To this end, Korfmann et al. (2023) developed and released their own forward-in-time simulator of genome-wide data, including neutral and selected polymorphisms, that makes use of Kelleher et al.’s (2018) tree sequence toolkit to keep track of gene genealogies. The originality of Korfmann et al.’s (2023) study is to provide new quantitative results for the effect of dormancy on the time to fixation of positively selected mutations, the shape of the genomic landscape in the vicinity of these mutations, and the temporal dynamics of selective sweeps. Their major finding is the prediction that germ banking creates narrower signatures of sweeps around positively selected sites, which are detectable for increased periods of time (as compared to a standard Wright-Fisher population). The availability of Korfmann et al.’s (2023) code will allow a wider range of parameter values to be explored, to extend their results to the particularities of the biology of many species. However, as they chose to extend the haploid coalescent model of Kaj et al. (2001), further development is needed to confirm the robustness of their results with a more realistic diploid model of seed dormancy. REFERENCES Evans, M. E. K., and J. J. Dennehy (2005) Germ banking: bet-hedging and variable release from egg and seed dormancy. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 80(4): 431-451. https://doi.org/10.1086/498282 Kaj, I., S. Krone, and M. Lascoux (2001) Coalescent theory for seed bank models. Journal of Applied Probability, 38(2): 285-300. https://doi.org/10.1239/jap/996986745 Kelleher, J., K. R. Thornton, J. Ashander, and P. L. Ralph (2018) Efficient pedigree recording for fast population genetics simulation. PLoS Computational Biology, 14(11): e1006581. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006581 Korfmann, K., D. Abu Awad, and A. Tellier (2023) Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweeps. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.26.489499 Vitalis, R., S. Glémin, and I. Olivieri (2004) When genes go to sleep: the population genetic consequences of seed dormancy and monocarpic perenniality. American Naturalist, 163(2): 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1086/381041 Živković, D., and A. Tellier (2018). All but sleeping? Consequences of soil seed banks on neutral and selective diversity in plant species. Mathematical Modelling in Plant Biology, 195-212. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99070-5_10 | Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweeps | Kevin Korfmann, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Seed banking (or dormancy) is a widespread bet-hedging strategy, generating a form of population overlap, which decreases the magnitude of genetic drift. The methodological complexity of integrating this trait impli... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics | Renaud Vitalis | 2022-05-23 13:01:57 | View | |

31 Mar 2022

Gene network robustness as a multivariate characterArnaud Le Rouzic https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.01564Genetic and environmental robustness are distinct yet correlated evolvable traits in a gene networkRecommended by Frédéric Guillaume based on reviews by Diogo Melo, Charles Mullon and Charles Rocabert based on reviews by Diogo Melo, Charles Mullon and Charles Rocabert

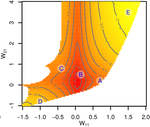

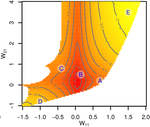

Organisms often show robustness to genetic or environmental perturbations. Whether these two components of robustness can evolve separately is the focus of the paper by Le Rouzic [1]. Using theoretical analysis and individual-based computer simulations of a gene regulatory network model, he shows that multiple aspects of robustness can be investigated as a set of pleiotropically linked quantitative traits. While genetically correlated, various robustness components (e.g., mutational, developmental, homeostasis) of gene expression in the regulatory network evolved more or less independently from each other under directional selection. The quantitative approach of Le Rouzic could explain both how unselected robustness components can respond to selection on other components and why various robustness-related features seem to have their own evolutionary history. Moreover, he shows that all components were evolvable, but not all to the same extent. Robustness to environmental disturbances and gene expression stability showed the largest responses while increased robustness to genetic disturbances was slower. Interestingly, all components were positively correlated and remained so after selection for increased or decreased robustness. This study is an important contribution to the discussion of the evolution of robustness in biological systems. While it has long been recognized that organisms possess the ability to buffer genetic and environmental perturbations to maintain homeostasis (e.g., canalization [2]), the genetic basis and evolutionary routes to robustness and canalization are still not well understood. Models of regulatory gene networks have often been used to address aspects of robustness evolution (e.g., [3]). Le Rouzic [1] used a gene regulatory network model derived from Wagner’s model [4]. The model has as end product the expression level of a set of genes influenced by a set of regulatory elements (e.g., transcription factors). The level and stability of expression are a property of the regulatory interactions in the network. Le Rouzic made an important contribution to the study of such gene regulation models by using a quantitative genetics approach to the evolution of robustness. He crafted a way to assess the mutational variability and selection response of the components of robustness he was interested in. Le Rouzic’s approach opens avenues to investigate further aspects of gene network evolutionary properties, for instance to understand the evolution of phenotypic plasticity. Le Rouzic also discusses ways to measure his different robustness components in empirical studies. As the model is about gene expression levels at a set of protein-coding genes influenced by a set of regulatory elements, it naturally points to the possibility of using RNA sequencing to measure the variation of gene expression in know gene networks and assess their robustness. Robustness could then be studied as a multidimensional quantitative trait in an experimental setting. References [1] Le Rouzic, A (2022) Gene network robustness as a multivariate character. arXiv: 2101.01564, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.01564 [2] Waddington CH (1942) Canalization of Development and the Inheritance of Acquired Characters. Nature, 150, 563–565. https://doi.org/10.1038/150563a0 [3] Draghi J, Whitlock M (2015) Robustness to noise in gene expression evolves despite epistatic constraints in a model of gene networks. Evolution, 69, 2345–2358. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12732 [4] Wagner A (1994) Evolution of gene networks by gene duplications: a mathematical model and its implications on genome organization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 91, 4387–4391. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.91.10.4387 | Gene network robustness as a multivariate character | Arnaud Le Rouzic | <p style="text-align: justify;">Robustness to genetic or environmental disturbances is often considered as a key property of living systems. Yet, in spite of being discussed since the 1950s, how robustness emerges from the complexity of genetic ar... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Theory, Genotype-Phenotype, Quantitative Genetics | Frédéric Guillaume | Charles Mullon, Charles Rocabert, Diogo Melo | 2021-01-11 17:48:20 | View |

23 Jun 2021

Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic driftLaurène Gay, Julien Dhinaut, Margaux Jullien, Renaud Vitalis, Miguel Navascués, Vincent Ranwez, and Joëlle Ronfort https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261230Separating adaptation from drift: A cautionary tale from a self-fertilizing plantRecommended by Christoph Haag based on reviews by Pierre Olivier Cheptou, Jon Agren and Stefan LaurentIn recent years many studies have documented shifts in phenology in response to climate change, be it in arrival times in migrating birds, budset in trees, adult emergence in butterflies, or flowering time in annual plants (Coen et al. 2018; Piao et al. 2019). While these changes are, in part, explained by phenotypic plasticity, more and more studies find that they involve also genetic changes, that is, they involve evolutionary change (e.g., Metz et al. 2020). Yet, evolutionary change may occur through genetic drift as well as selection. Therefore, in order to demonstrate adaptive evolutionary change in response to climate change, drift has to be excluded as an alternative explanation (Hansen et al. 2012). A new study by Gay et al. (2021) shows just how difficult this can be. The authors investigated a recent evolutionary shift in flowering time by in a population an annual plant that reproduces predominantly by self-fertilization. The population has recently been subjected to increased temperatures and reduced rainfalls both of which are believed to select for earlier flowering times. They used a “resurrection” approach (Orsini et al. 2013; Weider et al. 2018): Genotypes from the past (resurrected from seeds) were compared alongside more recent genotypes (from more recently collected seeds) under identical conditions in the greenhouse. Using an experimental design that replicated genotypes, eliminated maternal effects, and controlled for microenvironmental variation, they found said genetic change in flowering times: Genotypes obtained from recently collected seeds flowered significantly (about 2 days) earlier than those obtained 22 generations before. However, neutral markers (microsatellites) also showed strong changes in allele frequencies across the 22 generations, suggesting that effective population size, Ne, was low (i.e., genetic drift was strong), which is typical for highly self-fertilizing populations. In addition, several multilocus genotypes were present at high frequencies and persisted over the 22 generations, almost as in clonal populations (e.g., Schaffner et al. 2019). The challenge was thus to evaluate whether the observed evolutionary change was the result of an adaptive response to selection or may be explained by drift alone. Here, Gay et al. (2021) took a particularly careful and thorough approach. First, they carried out a selection gradient analysis, finding that earlier-flowering plants produced more seeds than later-flowering plants. This suggests that, under greenhouse conditions, there was indeed selection for earlier flowering times. Second, investigating other populations from the same region (all populations are located on the Mediterranean island of Corsica, France), they found that a concurrent shift to earlier flowering times occurred also in these populations. Under the hypothesis that the populations can be regarded as independent replicates of the evolutionary process, the observation of concurrent shifts rules out genetic drift (under drift, the direction of change is expected to be random). The study may well have stopped here, concluding that there is good evidence for an adaptive response to selection for earlier flowering times in these self-fertilizing plants, at least under the hypothesis that selection gradients estimated in the greenhouse are relevant to field conditions. However, the authors went one step further. They used the change in the frequencies of the multilocus genotypes across the 22 generations as an estimate of realized fitness in the field and compared them to the phenotypic assays from the greenhouse. The results showed a tendency for high-fitness genotypes (positive frequency changes) to flower earlier and to produce more seeds than low-fitness genotypes. However, a simulation model showed that the observed correlations could be explained by drift alone, as long as Ne is lower than ca. 150 individuals. The findings were thus consistent with an adaptive evolutionary change in response to selection, but drift could only be excluded as the sole explanation if the effective population size was large enough. The study did provide two estimates of Ne (19 and 136 individuals, based on individual microsatellite loci or multilocus genotypes, respectively), but both are problematic. First, frequency changes over time may be influenced by the presence of a seed bank or by immigration from a genetically dissimilar population, which may lead to an underestimation of Ne (Wang and Whitlock 2003). Indeed, the low effective size inferred from the allele frequency changes at microsatellite loci appears to be inconsistent with levels of genetic diversity found in the population. Moreover, high self-fertilization reduces effective recombination and therefore leads to non-independence among loci. This lowers the precision of the Ne estimates (due to a higher sampling variance) and may also violate the assumption of neutrality due to the possibility of selection (e.g., due to inbreeding depression) at linked loci, which may be anywhere in the genome in case of high degrees of self-fertilization. There is thus no definite answer to the question of whether or not the observed changes in flowering time in this population were driven by selection. The study sets high standards for other, similar ones, in terms of thoroughness of the analyses and care in interpreting the findings. It also serves as a very instructive reminder to carefully check the assumptions when estimating neutral expectations, especially when working on species with complicated demographies or non-standard life cycles. Indeed the issues encountered here, in particular the difficulty of establishing neutral expectations in species with low effective recombination, may apply to many other species, including partially or fully asexual ones (Hartfield 2016). Furthermore, they may not be limited to estimating Ne but may also apply, for instance, to the establishment of neutral baselines for outlier analyses in genome scans (see e.g, Orsini et al. 2012). References Cohen JM, Lajeunesse MJ, Rohr JR (2018) A global synthesis of animal phenological responses to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 8, 224–228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0067-3 Gay L, Dhinaut J, Jullien M, Vitalis R, Navascués M, Ranwez V, Ronfort J (2021) Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic drift. bioRxiv, 2020.08.21.261230, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261230 Hansen MM, Olivieri I, Waller DM, Nielsen EE (2012) Monitoring adaptive genetic responses to environmental change. Molecular Ecology, 21, 1311–1329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05463.x Hartfield M (2016) Evolutionary genetic consequences of facultative sex and outcrossing. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 29, 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12770 Metz J, Lampei C, Bäumler L, Bocherens H, Dittberner H, Henneberg L, Meaux J de, Tielbörger K (2020) Rapid adaptive evolution to drought in a subset of plant traits in a large-scale climate change experiment. Ecology Letters, 23, 1643–1653. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13596 Orsini L, Schwenk K, De Meester L, Colbourne JK, Pfrender ME, Weider LJ (2013) The evolutionary time machine: using dormant propagules to forecast how populations can adapt to changing environments. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28, 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2013.01.009 Orsini L, Spanier KI, Meester LD (2012) Genomic signature of natural and anthropogenic stress in wild populations of the waterflea Daphnia magna: validation in space, time and experimental evolution. Molecular Ecology, 21, 2160–2175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05429.x Piao S, Liu Q, Chen A, Janssens IA, Fu Y, Dai J, Liu L, Lian X, Shen M, Zhu X (2019) Plant phenology and global climate change: Current progresses and challenges. Global Change Biology, 25, 1922–1940. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14619 Schaffner LR, Govaert L, De Meester L, Ellner SP, Fairchild E, Miner BE, Rudstam LG, Spaak P, Hairston NG (2019) Consumer-resource dynamics is an eco-evolutionary process in a natural plankton community. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3, 1351–1358. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0960-9 Wang J, Whitlock MC (2003) Estimating Effective Population Size and Migration Rates From Genetic Samples Over Space and Time. Genetics, 163, 429–446. PMID: 12586728 Weider LJ, Jeyasingh PD, Frisch D (2018) Evolutionary aspects of resurrection ecology: Progress, scope, and applications—An overview. Evolutionary Applications, 11, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12563 | Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic drift | Laurène Gay, Julien Dhinaut, Margaux Jullien, Renaud Vitalis, Miguel Navascués, Vincent Ranwez, and Joëlle Ronfort | <p style="text-align: justify;">Resurrection studies are a useful tool to measure how phenotypic traits have changed in populations through time. If these traits modifications correlate with the environmental changes that occurred during the time ... | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Genotype-Phenotype, Phenotypic Plasticity, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Christoph Haag | 2020-08-21 17:26:59 | View | ||

28 Mar 2024

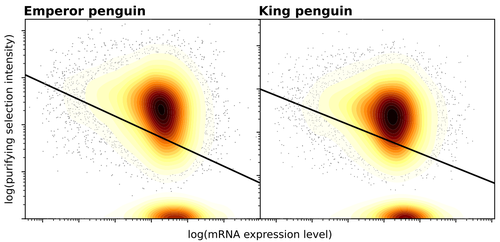

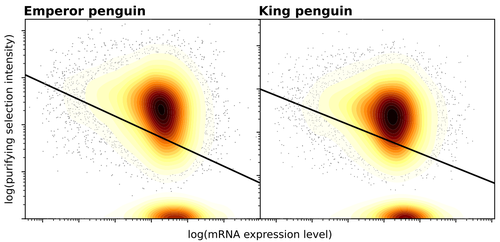

Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populationsEmiliano Trucchi, Piergiorgio Massa, Francesco Giannelli, Thibault Latrille, Flavia A.N. Fernandes, Lorena Ancona, Nils Chr Stenseth, Joan Ferrer Obiol, Josephine Paris, Giorgio Bertorelle, Celine Le Bohec https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552445Purifying selection on highly expressed genes in PenguinsRecommended by Bruce Rannala based on reviews by Tanja Pyhäjärvi and 1 anonymous reviewerGiven the general importance of protein expression levels, in cells it is widely accepted that gene expression levels are often a target of natural selection and that most mutations affecting gene expression levels are therefore likely to be deleterious [1]. However, it is perhaps less obvious that the strength of selection on the regulated genes themselves may be influenced by their expression levels. This might be due to harmful effects of misfolded proteins, for example, when higher protein concentrations exist in cells [2]. Recent studies have suggested that highly expressed genes accumulate fewer deleterious mutations; thus a positive relationship appears to exist between gene expression levels and the relative strength of purifying selection [3]. The recommended paper by Trucchi et al. [4] examines the relationship between gene expression, purifying selection and a third variable -- effective population size -- in populations of two species of penguin with different population sizes, the Emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) and the King penguin (A. patagonicus). Using transcriptomic data and computer simulations modeling selection, they examine patterns of nonsynonymous and synonymous segregating polymorphisms (p) across genes in the two populations, concluding that even in relatively small populations purifying selection has an important effect in eliminating deleterious mutations. References 1] Gilad Y, Oshlack A, and Rifkin SA. 2006. Natural selection on gene expression. Trends in Genetics 22: 456-461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.002 [4] Trucchi E, Massa P, Giannelli F, Latrille T, Fernandes FAN, Ancona L, Stenseth NC, Obiol JF, Paris J, Bertorelle G, and Le Bohec, C. 2023. Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populations. bioRxiv 2023.08.08.552445, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552445

| Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populations | Emiliano Trucchi, Piergiorgio Massa, Francesco Giannelli, Thibault Latrille, Flavia A.N. Fernandes, Lorena Ancona, Nils Chr Stenseth, Joan Ferrer Obiol, Josephine Paris, Giorgio Bertorelle, Celine Le Bohec | <p style="text-align: justify;">Purifying selection is the most pervasive type of selection, as it constantly removes deleterious mutations arising in populations, directly scaling with population size. Highly expressed genes appear to accumulate ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Bruce Rannala | 2023-08-09 17:53:03 | View | |

21 Nov 2022

Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughsElisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard https://doi.org/10.1101/679472The variety of bread-making practices promotes diversity conservation in food microbial communitiesRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Jeanne Ropars based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersDomesticated organisms are excellent models for understanding ecology and evolution and they are important for our food production and safety. While less studied than plants and animals, micro-organisms have also been domesticated, in particular for food fermentation [1]. The most studied domesticated micro-organism is the yeast used to make wine, beer and bread, Saccharomyces cerevisiae [2, 3, 4]. Filamentous fungi used for cheese-making have recently gained interest, for example Penicillium roqueforti used to make blue cheeses and P. camemberti to make soft cheeses [5, 6, 7, 8]. As for plants and animals, domestication has led to beneficial traits for food production in fermenting fungi, but also to bottlenecks and degeneration [6, 7, 9]; P. camemberti for example does not produce enough spores any more for optimal culture and inoculation and P. roqueforti has lost sexual fertility [9]. The loss of genetic diversity and of species diversity in our food production system is concerning for multiple reasons : i) it jeopardizes future improvement in the face of global changes ; ii) it causes the loss of evolved diversity during centuries under human selection, and therefore of beneficial characteristics and specificities that we may never be able to recover ; iii) it leads to degeneration in the few cultivated strains; iv) it impoverishes the diversity of our food products and local adaptation of production practices. The study of domesticated fungi used for food fermentation has focused so far on the evolution of lineages and on their metabolic specificities. Microbiological assemblages and species diversity have been much less studied, while they likely also have a strong impact on the quality and safety of final products. This study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] addresses this question, using an interdisciplinary participatory research approach including bakers, psycho-sociologists and microbiologists to analyse bread-making practices and their impact on microbial communities in sourdough. Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] identified two distinct groups of bread-making practices based on interviews and surveys, with farmer-like practices (low bread production, use of ancient wheat populations, manual kneading, working at ambient temperature, long fermentation periods and no use of commercial baker’s yeast) versus more intensive, artisanal-like practices. Metabarcoding and microbial culture-based analyses showed that the well-known baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was, surprisingly, not the most common species in French organic sourdoughs. Kazachstania was the most represented yeast genus over all sourdoughs, both in terms of read abundance and of species diversity. Kazachstania species were also often dominant in individual sourdoughs, but Saccharomyces uvarum or Torulaspora delbrueckii could also be the dominant yeast species. Metabarcoding analyses further revealed that the composition of the fungal communities differed between the farmer-like and more intensive practices, representing the first evidence of the influence of artisanal practices on microbial communities. The fungal communities were impacted by a combination of bread-making variables including the type of wheat varieties, the length of fermentation, the quantity of bread made per week and the use of commercial yeast. Maintaining on farm less intensive bread-making practices, may allow the preservation of typical species and phenotypic diversity in microbial communities in sourdough. Farmer-like practices did not lead to higher diversity within sourdoughs but, overall, the diversity of bread-making practices allow maintaining a larger diversity in sourdoughs. For example, different Kazachstania species were most abundant in sourdoughs from artisanal-like and farmer-like practices. Interviews with the bakers suggested the role of dispersal of Kazachstania species in shaping sourdough microbial communities, dispersal occurring by seed exchanges, sourdough mixing or gifts, bread-making training in common or working in one another’s bakery. Nikolai Vavilov [11] had already highlighted for crops the importance of isolated cultures and selection in different farms for generating and preserving crop diversity, but also the importance of seed exchange for fostering adaptation. Furthermore, one of the yeast frequently found in artisanal sourdoughs, Kazachstania humilis, displayed phenotypic differences between sourdough and non-sourdough strains, suggesting domestication. The sourdough strains exhibited significantly higher CO2 production rate and a lower fermentation latency-phase time. The study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] is thus novel and inspiring in showing the importance of interdisciplinary studies, combining metabarcoding, microbiology and interviews for assessing the composition and diversity of microbial communities in human-made food, and in revealing the impact of artisanal-like bread-making practices in preserving microbial community diversity. Interdisciplinary studies are still rare but have already shown the importance of combining ethno-ecology, biology and evolution to decipher the role of human practices on genetic diversity in crops, animals and food microorganisms and to help preserving genetic resources [12]. For example, in the case of the bread wheat Triticum aestivum, such interdisciplinary studies have shown that genetic diversity has been shaped by farmers’ seed diffusion and farming practices [13]. We need more of such interdisciplinary studies on the impact of farmer versus industrial agricultural and food-making practices as we urgently need to preserve the diversity of micro-organisms used in food production that we are losing at a rapid pace [6, 7, 14]. References [1] Dupont J, Dequin S, Giraud T, Le Tacon F, Marsit S, Ropars J, Richard F, Selosse M-A (2017) Fungi as a Source of Food. Microbiology Spectrum, 5, 5.3.09. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0030-2016 [2] Legras J-L, Galeote V, Bigey F, Camarasa C, Marsit S, Nidelet T, Sanchez I, Couloux A, Guy J, Franco-Duarte R, Marcet-Houben M, Gabaldon T, Schuller D, Sampaio JP, Dequin S (2018) Adaptation of S. cerevisiae to Fermented Food Environments Reveals Remarkable Genome Plasticity and the Footprints of Domestication. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1712–1727. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy066 [3] Bai F-Y, Han D-Y, Duan S-F, Wang Q-M (2022) The Ecology and Evolution of the Baker’s Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes, 13, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13020230 [4] Fay JC, Benavides JA (2005) Evidence for Domesticated and Wild Populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLOS Genetics, 1, e5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0010005 [5] Ropars J, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, López-Villavicencio M, Gouzy J, Sallet E, Dumas É, Lacoste S, Debuchy R, Dupont J, Branca A, Giraud T (2015) Adaptive Horizontal Gene Transfers between Multiple Cheese-Associated Fungi. Current Biology, 25, 2562–2569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.025 [6] Dumas E, Feurtey A, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Le Prieur S, Snirc A, Coton M, Thierry A, Coton E, Le Piver M, Roueyre D, Ropars J, Branca A, Giraud T (2020) Independent domestication events in the blue-cheese fungus Penicillium roqueforti. Molecular Ecology, 29, 2639–2660. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15359 [7] Ropars J, Didiot E, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Bennetot B, Coton M, Poirier E, Coton E, Snirc A, Le Prieur S, Giraud T (2020) Domestication of the Emblematic White Cheese-Making Fungus Penicillium camemberti and Its Diversification into Two Varieties. Current Biology, 30, 4441-4453.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.082 [8] Caron T, Piver ML, Péron A-C, Lieben P, Lavigne R, Brunel S, Roueyre D, Place M, Bonnarme P, Giraud T, Branca A, Landaud S, Chassard C (2021) Strong effect of Penicillium roqueforti populations on volatile and metabolic compounds responsible for aromas, flavor and texture in blue cheeses. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 354, 109174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109174 [9] Ropars J, Lo Y-C, Dumas E, Snirc A, Begerow D, Rollnik T, Lacoste S, Dupont J, Giraud T, López-Villavicencio M (2016) Fertility depression among cheese-making Penicillium roqueforti strains suggests degeneration during domestication. Evolution, 70, 2099–2109. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13015 [10] Michel E, Masson E, Bubbendorf S, Lapicque L, Nidelet T, Segond D, Guézenec S, Marlin T, Devillers H, Rué O, Onno B, Legrand J, Sicard D, Bakers TP (2022) Artisanal and farmer bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs. bioRxiv, 679472, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/679472 [11] Vavilov NI, Vavylov MI, Dorofeev VF (1992) Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants. Cambridge University Press. [12] Saslis-Lagoudakis CH, Clarke AC (2013) Ethnobiology: the missing link in ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28, 67–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.10.017 [13] Thomas M, Demeulenaere E, Dawson JC, Khan AR, Galic N, Jouanne-Pin S, Remoue C, Bonneuil C, Goldringer I (2012) On-farm dynamic management of genetic diversity: the impact of seed diffusions and seed saving practices on a population-variety of bread wheat. Evolutionary Applications, 5, 779–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-4571.2012.00257.x [14] Demeulenaere É, Lagrola M (2021) Des indicateurs pour accompagner “ les éleveurs de microbes” : Une communauté épistémique face au problème des laits “ paucimicrobiens ” dans la production fromagère au lait cru (1995-2015). Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances, 15. http://journals.openedition.org/rac/24953 | Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs | Elisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Preserving microbial diversity in food systems is one of the many challenges to be met to achieve food security and quality. Although industrialization led to the selection and spread of specific fermenting microbia... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology | Tatiana Giraud | 2022-01-27 14:53:08 | View | |

03 Oct 2023

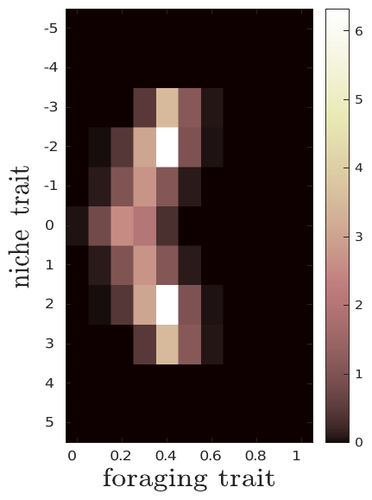

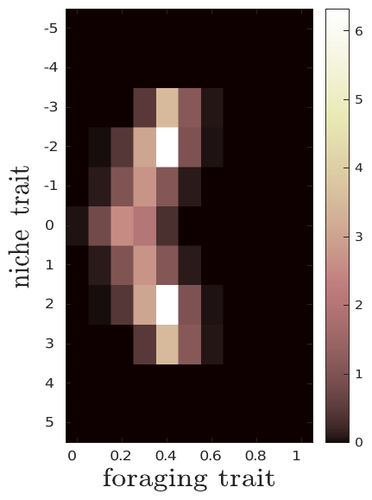

The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer modelLéo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Océane Guillot, Erwan Faou, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Ibanez https://doi.org/10.32942/X2QG7MEvolution and consequences of plastic foraging behavior in consumer-resource ecosystemsRecommended by François Rousset based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersPlastic responses of organisms to their environment may be maladaptive in particular when organisms are exposed to new environments. Phenotypic plasticity may also have opposite effects on the adaptive response of organisms to environmental changes: whether phenotypic plasticity favors or hinders such adaptation depends on a balance between the ability of the population to respond to the change non-genetically in the short term, and the weakened genetic response to environmental change. These topics have received continued attention, particularly in the context of climate change (e.g., Chevin et al. 2013, Duputié et al., 2015, Vinton et al . 2022). In their work, Ledru et al. focus on the adaptive nature of plastic behavior and on its consequences in a consumer-resource ecosystem. As they emphasize, previous works have found that plastic foraging promotes community stability, but these did not consider plasticity as an evolving trait, so Ledru et al. set out to test whether this conclusion holds when both plastic foraging and niche traits of consumers and resources evolve (though ultimately, their new conclusions may not all depend on plasticity evolving). Along the way, they first seek to clarify when such plasticity will evolve, and how it affects the evolution of the niche diversity of consumers and resources, before turning to the question of consumer persistence. The model is rather complex, as three traits are allowed to evolve, and the resource uptake expressed through plastic behavior has its own dynamics affected by some form of social learning. Classically, in models of niche evolution, a consumer's efficiency in exploiting a resource characterized by a trait y (here, the resource's individual niche trait), has been described in terms of location-scale (typically Gaussian) kernels, with mean x (the consumer's individual niche trait) specifying the most efficiently exploited resource, and with variance characterizing individual niche breadth. The evolution of the variance has been considered in some previous models but is assumed to be fixed here. Rather, the new model considers the evolution of the distribution of resource traits, of the consumer's individual niche trait (which is not plastic), and of a "plastic foraging trait" that controls the relative time spent foraging plastically versus foraging randomly. When foraging plastically, the consumers modify their foraging effort towards the type of resource that maximizes their energy intake. in some previous models, the effect of variation in the extent of plastic foraging was already considered, but the evolution of allocation to a plastic foraging strategy versus random foraging was not considered. The model is formulated through reaction-diffusion equations, and its dynamics is investigated by numerical integration. Foraging plasticity readily evolves, when resources vary widely enough, competition for resources is strong, and the cost of plasticity is weak. This means in particular that a large individual niche width of consumers selects for increased plastic foraging, as the evolution of plastic foraging leads to reduced niche overlap between consumers. The evolution of plastic foraging itself generally, though not always, favors the diversification of the niche traits of consumers and of resources. There is thus a positive feedback loop between plastic foraging and resource diversity. Ledru et al. conclude that the total niche width of the consumer population should also correlate with the evolution of plastic foraging, an implication which they relate to the so-called niche variation hypothesis and to empirical tests of it. The joint evolution of the consumer's individual niche trait and plastic foraging trait generates a striking pattern within populations: consumers whose individual niche trait is at an edge of the resource distribution forage more plastically. The authors observe that this relatively simple prediction has not been subjected to any empirical test. Returning to the question of consumer persistence, Ledru et al. evaluate this persistence when consumer mortality increases, and in response to either gradual or sudden environmental changes. These different perturbations all reduce the benefits of plastic foraging. The effect of plastic foraging on stability are complex, being negative or positive effect depending on the type of disturbance, and in particular the ecosystem has a lower sustainable rate of environmental change in the presence of plastic foraging. However, allowing the evolutionary regression of plastic foraging then has a comparatively positive effect on persistence. Despite the substantial effort devoted to analyzing this complex model, relaxing some of its assumptions would likely reveal further complexities. Notably, the overall effect of plasticity on consumer persistence depends on effects already encountered in models of the adaptive response of single species to environmental change: a fast non-genetic response in the short term versus a weakened genetic response in the longer term. The overall balance between these opposite effects on adaptation may be difficult to predict robustly. In the case of a constant rate of environmental change, the results of the present model depend on a lag load between the trait changes of consumer and resource populations, and the extent of the lag may also depend on many factors, such as the extent of genetic variation (e.g., Bürger & Lynch, 1995) for niche traits in consumers and resources. Here, the same variance of mutational effects was assumed for all three evolving traits. Further, spatial environmental variation, a central issue in studies of adaptive responses to environmental changes (e.g., Parmesan, 2006, Zhu et al., 2012), was not considered. Finally, the rate of adjustment of effort by consumers with given niche trait and plastic foraging trait values was assumed proportional to the density of consumers with such trait values. This was justified as a way of accounting for the use of social cues during foraging, but to the extent that they occur, social effects could manifest themselves through other learning dynamics. In conclusion, Ledru et al. have addressed a broad range of questions, suggesting new empirical tests of behavioural patterns on one side, and recovering in the context of community response to environmental changes a complexity that could be expected from earlier works on adaptive responses of organisms but that has been overlooked by previous works on community effects of phenotypic plasticity. References Bürger, R. and Lynch, M. (1995), Evolution and extinction in a changing environment: a quantitative-genetic analysis. Evolution, 49: 151-163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1995.tb05967.x Chevin, L.-M., Collins, S. and Lefèvre, F. (2013), Phenotypic plasticity and evolutionary demographic responses to climate change: taking theory out to the field. Funct Ecol, 27: 967-979. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02043.x Duputié, A., Rutschmann, A., Ronce, O. and Chuine, I. (2015), Phenological plasticity will not help all species adapt to climate change. Glob Change Biol, 21: 3062-3073. https://doi-org.inee.bib.cnrs.fr/10.1111/gcb.12914 Ledru, L., Garnier, J., Guillot, O., Faou, E., & Ibanez, S. (2023). The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer model. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2QG7M Parmesan, C. (2006) Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change Vinton, A.C., Gascoigne, S.J.L., Sepil, I., Salguero-Gómez, R., (2022) Plasticity’s role in adaptive evolution depends on environmental change components. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 37: 1067-1078. Zhu, K., Woodall, C.W. and Clark, J.S. (2012), Failure to migrate: lack of tree range expansion in response to climate change. Glob Change Biol, 18: 1042-1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02571.x | The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer model | Léo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Océane Guillot, Erwan Faou, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Ibanez | <p style="text-align: justify;">Phenotypic plasticity has important ecological and evolutionary consequences. In particular, behavioural phenotypic plasticity such as plastic foraging (PF) by consumers, may enhance community stability. Yet little ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | François Rousset | 2023-03-25 12:04:08 | View | |

01 Jul 2022

Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fuscaKamil S. Jaron, Christina N. Hodson, Jacintha Ellers, Stuart JE Baird, Laura Ross https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.12.468426Pressing NGS data through the mill of Kmer spectra and allelic coverage ratios in order to scan reproductive modes in non-model speciesRecommended by Nicolas Bierne based on reviews by Paul Simion and 2 anonymous reviewersThe genomic revolution has given us access to inexpensive genetic data for any species. Simultaneously we have lost the ability to easily identify chimerism in samples or some unusual deviations from standard Mendelian genetics. Methods have been developed to identify sex chromosomes, characterise the ploidy, or understand the exact form of parthenogenesis from genomic data. However, we rarely consider that the tissues we extract DNA from could be a mixture of cells with different genotypes or karyotypes. This can nonetheless happen for a variety of (fascinating) reasons such as somatic chromosome elimination, transmissible cancer, or parental genome elimination. Without a dedicated analysis, it is very easy to miss it. In this preprint, Jaron et al. (2022) used an ingenious analysis of whole individual NGS data to test the hypothesis of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca. The authors suspected that a high fraction of the whole body of males is made of sperm in this species and if this species undergoes paternal genome elimination, we would expect that sperm would only contain maternally inherited chromosomes. Given the reference genome was highly fragmented, they developed a two-tissue model to analyse Kmer spectra and obtained confirmation that around one-third of the tissue was sperm in males. This allowed them to test whether coverage patterns were consistent with the species exhibiting paternal genome elimination. They combined their estimation of the fraction of haploid tissue with allele coverages in autosomes and the X chromosome to obtain support for a bias toward one parental allele, suggesting that all sperm carries the same parental haplotype. It could be the maternal or the paternal alleles, but paternal genome elimination is most compatible with the known biology of Arthropods. SNP calling was used to confirm conclusions based on the analysis of the raw pileups. I found this study to be a good example of how a clever analysis of Kmer spectra and allele coverages can provide information about unusual modes of reproduction in a species, even though it does not have a well-assembled genome yet. As advocated by the authors, routine inspection of Kmer spectra and allelic read-count distributions should be included in the best practice of NGS data analysis. They provide the method to identify paternal genome elimination but also the way to develop similar methods to detect another kind of genetic chimerism in the avalanche of sequence data produced nowadays. References Jaron KS, Hodson CN, Ellers J, Baird SJ, Ross L (2022) Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca. bioRxiv, 2021.11.12.468426, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.12.468426 | Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca | Kamil S. Jaron, Christina N. Hodson, Jacintha Ellers, Stuart JE Baird, Laura Ross | <p style="text-align: justify;">Paternal genome elimination (PGE) - a type of reproduction in which males inherit but fail to pass on their father’s genome - evolved independently in six to eight arthropod clades. Thousands of species, including s... | Genome Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Nicolas Bierne | 2021-11-18 00:09:43 | View | ||

30 May 2023

slendr: a framework for spatio-temporal population genomic simulations on geographic landscapesMartin Petr, Benjamin C. Haller, Peter L. Ralph, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.20.485041A new powerful tool to easily encode the geo-spatial dimension in population genetics simulationsRecommended by Emiliano Trucchi based on reviews by Liisa Loog and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Liisa Loog and 2 anonymous reviewers

Models explaining the evolutionary processes operating in living beings are often impossible to test in the real world. This is mainly because of the long time (i.e., the number of generations) which is necessary for evolution to unfold. In addition, any such experiment would require a large number of individuals and, more importantly, many replicates to account for the inherent variance of the evolutionary processes under investigation. Only organisms with fast generation times and favourable rearing conditions can be used to explicitly test for specific evolutionary hypotheses. Computer simulations have filled this gap, revolutionising experimental testing in evolutionary biology by integrating genetic models into complex population dynamics, which can be run for (potentially) any length of time. Without going into an extensive description of the many available approaches for population genetics simulations (an exhaustive review can be found in Hoban et al 2012), three main aspects are, in my opinion, important for categorising and choosing one simulation approach over another. The first concerns the basic distinction between coalescent-based and individual-based simulators: the former being an efficient approach, which simulates back in time the coalescence events of a sample of homologous DNA fragments, while the latter is a more computationally intensive approach where all of the individuals (and their underlying genetic/genomic features) in the population are simulated forward-in-time, generation after generation. The second aspect concerns the simulation of natural selection. Although natural selection can be integrated into backward-in-time simulations, it is more realistically implemented as individual-based fitness in forward-in-time simulators. The third point, which has been often overlooked in evolutionary simulations, is about the possibility to design a simulation scenario where individuals and populations can exploit a physical (geographical) space. Amongst the coalescent-based simulators, SPLATCHE (Currat et al 2004), and its derivatives, is one of the few simulation tools deploying the coalescence process in sub-demes which are all connected by migration, thus getting as close as possible to a spatially-explicit population. On the other hand, individual-based simulators, whose development followed the increasing power of computational machines, offer a great opportunity to include spatio-temporal dynamics within a genomic simulation model. One of the most realistic and efficient individual-based forward-in-time simulators available is SLiM (Haller and Messer 2017), which allows users to implement simulations in arbitrarily complex spaces. Here, the more challenging part is encoding the spatially-explicit scenarios using the SLiM-specific EIDOS language. The new R package slendr (Petr et al 2022) offers a practical solution to this issue. By wrapping different tools into a well-known scripting language, slendr allows the design of spatiotemporal simulation scenarios which can be directly executed in the individual-based SLiM simulator, and the output stored with modern tree-sequence analysis tools (tskit; Kellerer et al 2018). Alternatively, simulations of non-spatial models can be run using a coalescent-based algorithm (msprime; Baumdicker et al 2022). The main advantage of slendr is that the whole simulative experiment can be performed entirely in the R environment, taking advantage of the many libraries available for geospatial and genomic data analysis, statistics, and visualisation. The open-source nature of this package, whose main aim is to make complex population genomics modelling more accessible, and the vibrant community of SLiM and tskit users will very likely make slendr widely used amongst the molecular ecology and evolutionary biology communities. Slendr handles real Earth cartographic data where users can design realistic demographic processes which characterise natural populations (i.e., expansions, displacement of large populations, interactions among populations, migrations, population splits, etc.) by changing spatial population boundaries across time and space. All in all, slendr is a very flexible and scalable framework to test the accuracy of spatial models, hypotheses about demography and selection, and interactions between organisms across space and time. REFERENCES Baumdicker, F., Bisschop, G., Goldstein, D., Gower, G., Ragsdale, A. P., Tsambos, G., ... & Kelleher, J. (2022). Efficient ancestry and mutation simulation with msprime 1.0. Genetics, 220(3), iyab229. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyab229 Currat, M., Ray, N., & Excoffier, L. (2004). SPLATCHE: a program to simulate genetic diversity taking into account environmental heterogeneity. Molecular Ecology Notes, 4(1), 139-142. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-8286.2003.00582.x Haller, B. C., & Messer, P. W. (2017). SLiM 2: flexible, interactive forward genetic simulations. Molecular biology and evolution, 34(1), 230-240. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw211 Hoban, S., Bertorelle, G., & Gaggiotti, O. E. (2012). Computer simulations: tools for population and evolutionary genetics. Nature Reviews Genetics, 13(2), 110-122. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3130 Kelleher, J., Thornton, K. R., Ashander, J., & Ralph, P. L. (2018). Efficient pedigree recording for fast population genetics simulation. PLoS computational biology, 14(11), e1006581. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006581 Petr, M., Haller, B. C., Ralph, P. L., & Racimo, F. (2023). slendr: a framework for spatio-temporal population genomic simulations on geographic landscapes. bioRxiv, 2022.03.20.485041, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.20.485041 | slendr: a framework for spatio-temporal population genomic simulations on geographic landscapes | Martin Petr, Benjamin C. Haller, Peter L. Ralph, Fernando Racimo | <p style="text-align: justify;">One of the goals of population genetics is to understand how evolutionary forces shape patterns of genetic variation over time. However, because populations evolve across both time and space, most evolutionary proce... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Theory, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Emiliano Trucchi | 2022-09-14 12:57:56 | View | |

22 Mar 2022

Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus CorbiculaVastrade M., Etoundi E., Bournonville T., Colinet M., Debortoli N., Hedtke S.M., Nicolas E., Pigneur L.-M., Virgo J., Flot J.-F., Marescaux J. and Van Doninck K. https://doi.org/10.1101/590836Strange reproductive modes and population geneticsRecommended by Chris Jiggins based on reviews by Arnaud Estoup, Simon Henry Martin and 2 anonymous reviewersThere are many organisms that are asexual or have unusual modes of reproduction. One such quasi-sexual reproductive mode is androgenesis, in which the offspring, after fertilization, inherits only the entire paternal nuclear genome. The maternal genome is ditched along the way. One group of organisms which shows this mode of reproduction are clams in the genus Corbicula, some of which are androecious, while others are dioecious and sexual. The study by Vastrade et al. (2022) describes population genetic patterns in these clams, using both nuclear and mitochondrial sequence markers. In contrast to what might be expected for an asexual lineage, there is evidence for significant genetic mixing between populations. In addition, there is high heterozygosity and evidence for polyploidy in some lineages. Overall, the picture is complicated! However, what is clear is that there is far more genetic mixing than expected. One possible mechanism by which this could occur is 'nuclear capture' where there is a mixing of maternal and paternal lineages after fertilization. This can sometimes occur as a result of hybridization between 'species', leading to further mixing of divergent lineages. Thus the group is clearly far from an ancient asexual lineage - recombination and mixing occur with some regularity. The study also analyzed recent invasive populations in Europe and America. These had reduced genetic diversity, but also showed complex patterns of allele sharing suggesting a complex origin of the invasive lineages. In the future, it will be exciting to apply whole genome sequencing approaches to systems such as this. There are challenges in interpreting a handful of sequenced markers especially in a system with polyploidy and considerable complexity, and whole-genome sequencing could clarify some of the outstanding questions, Overall, this paper highlights the complex genetic patterns that can result through unusual reproductive modes, which provides a challenge for the field of population genetics and for the recognition of species boundaries. References Vastrade M, Etoundi E, Bournonville T, Colinet M, Debortoli N, Hedtke SM, Nicolas E, Pigneur L-M, Virgo J, Flot J-F, Marescaux J, Doninck KV (2022) Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus Corbicula. bioRxiv, 590836, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/590836 | Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus Corbicula | Vastrade M., Etoundi E., Bournonville T., Colinet M., Debortoli N., Hedtke S.M., Nicolas E., Pigneur L.-M., Virgo J., Flot J.-F., Marescaux J. and Van Doninck K. | <p style="text-align: justify;">“Occasional” sexuality occurs when a species combines clonal reproduction and genetic mixing. This strategy is predicted to combine the advantages of both asexuality and sexuality, but its actual consequences on the... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Hybridization / Introgression, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Chris Jiggins | 2019-03-29 15:42:56 | View | |

25 Sep 2023

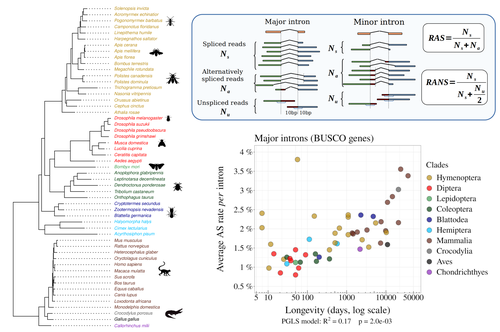

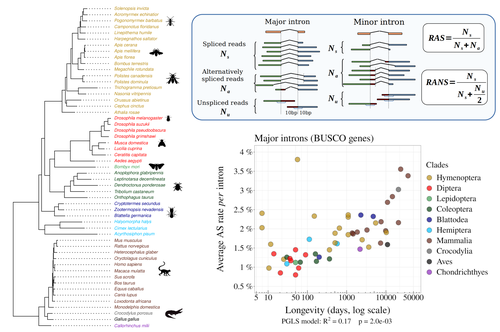

Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoansFlorian Benitiere, Anamaria Necsulea, Laurent Duret https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519597The drift barrier hypothesis and the limits to alternative splicing accuracyRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Lars M. Jakt and 2 anonymous reviewersAccurate information flow is central to living systems. The continuity of genomes through generations as well as the reproducible functioning and survival of the individual organisms require a faithful information transfer during replication, transcription and translation. The differential efficiency of natural selection against “mistakes” results in decreasing fidelity rates for replication, transcription and translation. At each level in the information flow chain (replication, transcription, translation), numerous complex molecular systems have evolved and been selected for preventing, identifying and, when possible, correcting or removing such “mistakes” arising during information transfer. However, fidelity cannot be improved ad infinitum. First, because of the limits imposed by the physical nature of the processes of copying and recoding information over different molecular supports: all mechanisms ensuring fidelity during biological information transfer ultimately rely on chemical kinetics and thermodynamics. The more accurate a copying process is, the lower the synthesis rate and the higher the energetic cost of correcting errors. Second, because of the limits imposed by random genetic drift: natural selection cannot effectively act on an allele that contributes with a small differential advantage unless effective population size is large. If s <1/Ne (or s <1/(2Ne) in diploids) the allele frequency in the population is de facto subject to neutral drift processes. In their preprint “Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans”, Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret explore the validity of this last mentioned “drift barrier” hypothesis for the case study of alternative splicing diversity in eukaryotes (Bénitière et al. 2022). Splicing refers to an ensemble of eukaryotic molecular processes mediated by a large number of proteins and ribonucleoproteins and involving nucleotide sequence recognition, that uses as a molecular substrate a precursor messenger RNA (mRNA), directly transcribed from the DNA, and produces a mature mRNA by removing introns and joining exons (Chow et al. 1977). Alternative splicing refers to the case in which different molecular species of mature mRNAs can be produced, either by cis-splicing processes acting on the same precursor mRNA, e.g. by varying the presence/absence of different exons or by varying the exon-exon boundaries, or by trans-splicing processes, joining exons from different precursor mRNA molecules. The diversity of mRNA molecular species generated by alternative splicing enlarges the molecular phenotypic space that can be generated from the same genotype. In humans, alternative splicing occurs in around 95% of the ca. 20,000 genes, resulting in ca. 100,000 medium-to-high abundance transcripts (Pan et al. 2008). In multicellular organisms, the frequency of alternatively spliced mRNAs varies between tissues and across ontogeny, often in a switch-like pattern (Wang et al. 2008). In the molecular and cell biology community, it is commonly accepted that splice variants contribute with specific functions (Marasco and Kornblihtt 2023) although there exists a discussion around the functional nature of low-frequency splice variants (see for instance the debate between Tress et al. 2017 and Blencowe 2017). The origin, diversity, regulation and evolutionary advantage of alternative splicing constitutes thus a playground of the selectionist-neutralist debate, with one extreme considering that most splice variants are mere “mistakes” of the splicing process (Pickrell et al. 2010), and the other extreme considering that alternative splicing is at the core of complexity in multicellular organisms, as it increases the genome coding potential and allows for a large repertoire of cell types (Chen et al. 2014). In their manuscript, Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret set the cursor towards the neutralist end of the gradient and test the hypothesis of whether the high alternative splice rate in “complex” organisms corresponds to a high rate of splicing “mistakes”, arising from the limit imposed by the drift barrier effect on the power of natural selection to increase accuracy (Bush et al. 2017). In their preprint, the authors convincingly show that in metazoans a fraction of the variation of alternative splicing rate is explained by variation in proxies of population size, so that species with smaller Ne display higher alternative splice rates. They communicate further that abundant splice variants tend to preserve the reading frame more often than low-frequency splice variants, and that the nucleotide splice signals in abundant splice variants display stronger evidence of purifying selection than those in low-frequency splice variants. From all the evidence presented in the manuscript, the authors interpret that “variation in alternative splicing rate is entirely driven by variation in the efficacy of selection against splicing errors”. The authors honestly present some of the limitations of the data used for the analyses, regarding i) the quality of the proxies used for Ne (i.e. body length, longevity and dN/dS ratio); ii) the heterogeneous nature of the RNA sequencing datasets (full organisms, organs or tissues; different life stages, sexes or conditions); and iii) mostly short RNA reads that do not fully span individual introns. Further, data from bacteria do not verify the herein communicated trends, as it has been shown that bacterial species with low population sizes do not display higher transcription error rates (Traverse and Ochman 2016). Finally, it will be extremely interesting to introduce a larger evolutionary perspective on alternative splicing rates encompassing unicellular eukaryotes, in which an intriguing interplay between alternative splicing and gene duplication has been communicated (Hurtig et al. 2020). The manuscript from Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret makes a significant advance to our understanding of the diversity, the origin and the physiology of post-transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms by emphasising the fundamental role of non-adaptive evolutionary processes and the upper limits to splicing accuracy set by genetic drift. References Bénitière F, Necsulea A, Duret L. 2023. Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519597 Blencowe BJ. 2017. The Relationship between Alternative Splicing and Proteomic Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci 42:407–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2017.04.001 Bush SJ, Chen L, Tovar-Corona JM, Urrutia AO. 2017. Alternative splicing and the evolution of phenotypic novelty. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 372:20150474. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0474 Chen L, Bush SJ, Tovar-Corona JM, Castillo-Morales A, Urrutia AO. 2014. Correcting for differential transcript coverage reveals a strong relationship between alternative splicing and organism complexity. Mol Biol Evol 31:1402–1413. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu083 Chow LT, Gelinas RE, Broker TR, Roberts RJ. 1977. An amazing sequence arrangement at the 5’ ends of adenovirus 2 messenger RNA. Cell 12:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(77)90180-5 Hurtig JE, Kim M, Orlando-Coronel LJ, Ewan J, Foreman M, Notice L-A, Steiger MA, van Hoof A. 2020. Origin, conservation, and loss of alternative splicing events that diversify the proteome in Saccharomycotina budding yeasts. RNA 26:1464–1480. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.075655.120 Marasco LE, Kornblihtt AR. 2023. The physiology of alternative splicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 24:242–254. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-022-00545-z Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. 2008. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet 40:1413–1415. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.259 Pickrell JK, Pai AA, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. 2010. Noisy splicing drives mRNA isoform diversity in human cells. PLoS Genet 6:e1001236. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001236 Traverse CC, Ochman H. 2016. Conserved rates and patterns of transcription errors across bacterial growth states and lifestyles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:3311–3316. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1525329113 Tress ML, Abascal F, Valencia A. 2017. Alternative Splicing May Not Be the Key to Proteome Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci 42:98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2016.08.008 Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP, Burge CB. 2008. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 456:470–476. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07509 | Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans | Florian Benitiere, Anamaria Necsulea, Laurent Duret | <p style="text-align: justify;">Most eukaryotic genes undergo alternative splicing (AS), but the overall functional significance of this process remains a controversial issue. It has been noticed that the complexity of organisms (assayed by the nu... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Ignacio Bravo | Anonymous | 2022-12-12 14:00:01 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer