Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers▼ | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

30 Oct 2023

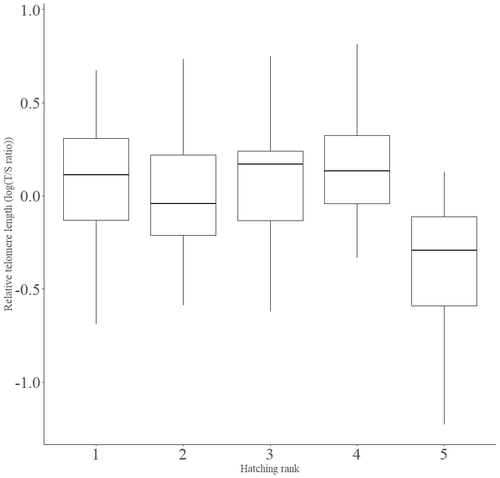

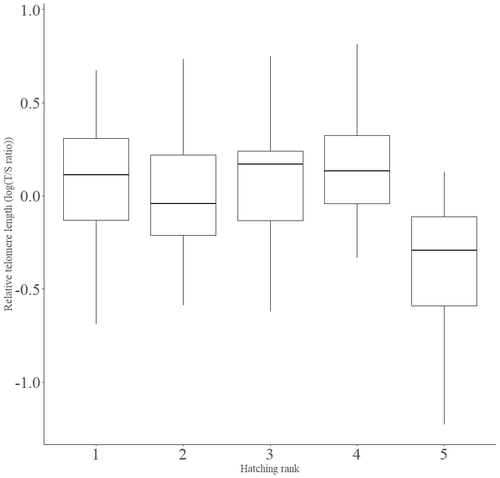

Telomere length vary with sex, hatching rank and year of birth in little owls, Athene noctuaFrançois Criscuolo, Inès Fache, Bertrand Scaar, Sandrine Zahn, Josefa Bleu https://doi.org/10.32942/X2BS3SDeciphering the relative contribution of environmental and biological factors driving telomere length in nestlingsRecommended by Jean-François Lemaitre based on reviews by Florentin Remot and 1 anonymous reviewerThe search for physiological markers of health and survival in wild animal populations is attracting a great deal of interest. At present, there is no (and may never be) consensus on such a single, robust marker but of all the proposed physiological markers, telomere length is undoubtedly the most widely studied in the field of evolutionary ecology (Monaghan et al., 2022). Broadly speaking, telomeres are non-coding DNA sequences located at the end of chromosomes in eukaryotes, protecting genomic DNA against oxidative stress and various detrimental processes (e.g. DNA end-joining) and thus maintaining genome stability (Blackburn et al., 2015). However, in most somatic cells from the vast majority of the species, telomere sequences are not replicated and telomere length progressively declines with increased age (Remot et al., 2022). This shortening of telomere length upon a critical level is causally linked to cellular senescence and has been invoked as one of the primary causes of the aging process (López-Otín et al., 2023). Studies performed in both captive and wild populations of animals have further demonstrated that short telomeres (or telomere sequences with a fast attrition rate) are to some extent associated with an increased risk of mortality, even if the magnitude of this association largely differs between species and populations (Wilbourn et al., 2018). The repeated observations of associations between telomere length and mortality risk have called for studies seeking to identify the ecological and biological factors that – beyond chronological age – shape the between-individual variability in telomere length. A wide spectrum of environmental stressors such as the level of exposure to pathogens or the degree of human disturbances has been proposed as possible modulators of telomere dynamics (see Chatelain et al., 2019). However, within species, the relative contribution of various ecological and biological factors on telomere length has been rarely quantified. In that context, the study of Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) constitutes a timely attempt to decipher the relative contribution of environmental and biological factors driving telomere length in nestlings (i.e. when individuals are between 15 and 35 days of age) from a wild population of little owls, Athene noctua. In addition to chronological age, Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) analysed the effects of two environmental variables (i.e. cohort and habitat quality) as well as three life history traits (i.e. hatching rank, sex and body condition). Among these traits, sex was found to impact nestling’s telomere length with females carrying longer telomeres than males. Traditionally, the among-individuals variability in telomere length during the juvenile period is interpreted as a direct consequence of differences in growth allocation. Fast-growing individuals are typically supposed to undergo more cell divisions and a higher exposure to oxidative stress, which ultimately shortens telomeres (Monaghan & Ozanne, 2018). Whether - despite a slightly female-biased sexual size dimorphism - male little owls display a condensed period of fast growth that could explain their shorter telomere is yet to be determined. Future studies should also explore the consequences of these sex differences in telomere length in terms of mortality risk. In birds, it has been observed that telomere length during early life can predict lifespan (see Heidinger et al., 2012 in zebra finches, Taeniopygia guttata), suggesting that females little owls might live longer than their conspecific males. Yet, adult mortality is generally female-biased in birds (Liker & Székely, 2005) and whether little owls constitute an exception to this rule - possibly mediated by sex-specific telomere dynamics - remains to be explored. Quite surprisingly, the present study in little owls did not evidence any clear effect of environmental conditions on nestling’s telomere length, at both temporal and special scales. While a trend for a temporal effect was detected with telomere length being slightly shorter for nestling born the last year of the study (out of 4 years analysed), habitat quality (measured by the proportion of meadow and orchards in the nest environment) had absolutely no impact on nestling telomere length. Recently published studies in wild populations of vertebrates have highlighted the detrimental effects of harsh environmental conditions on telomere length (e.g. Dupoué et al., 2022 in common lizards, Zootoca vivipara), arguing for a key role of telomere dynamics in the emerging field of conservation physiology. While we can recognize the relevance of such an integrative approach, especially in the current context of climate change, the study by Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) reminds us that the relationships between environmental conditions and telomere dynamics are far from straightforward. Depending on the species and its life history, telomere length in early life could indeed capture very different environmental signals. References Blackburn, E. H., Epel, E. S., & Lin, J. (2015). Human telomere biology: A contributory and interactive factor in aging, disease risks, and protection. Science, 350(6265), 1193-1198. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab3389 | Telomere length vary with sex, hatching rank and year of birth in little owls, *Athene noctua* | François Criscuolo, Inès Fache, Bertrand Scaar, Sandrine Zahn, Josefa Bleu | <p>Telomeres are non-coding DNA sequences located at the end of linear chromosomes, protecting genome integrity. In numerous taxa, telomeres shorten with age and telomere length (TL) is positively correlated with longevity. Moreover, TL is also af... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Jean-François Lemaitre | 2023-03-07 09:44:32 | View | |

03 Oct 2023

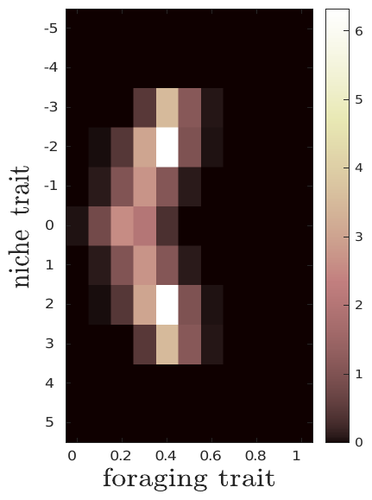

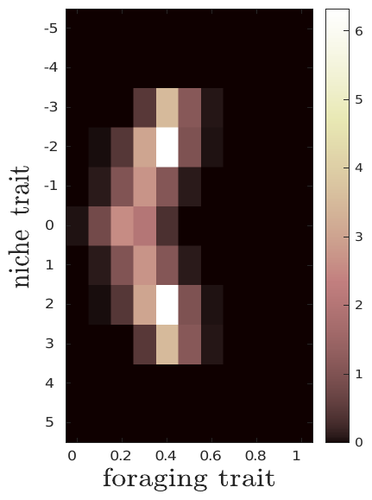

The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer modelLéo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Océane Guillot, Erwan Faou, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Ibanez https://doi.org/10.32942/X2QG7MEvolution and consequences of plastic foraging behavior in consumer-resource ecosystemsRecommended by François Rousset based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersPlastic responses of organisms to their environment may be maladaptive in particular when organisms are exposed to new environments. Phenotypic plasticity may also have opposite effects on the adaptive response of organisms to environmental changes: whether phenotypic plasticity favors or hinders such adaptation depends on a balance between the ability of the population to respond to the change non-genetically in the short term, and the weakened genetic response to environmental change. These topics have received continued attention, particularly in the context of climate change (e.g., Chevin et al. 2013, Duputié et al., 2015, Vinton et al . 2022). In their work, Ledru et al. focus on the adaptive nature of plastic behavior and on its consequences in a consumer-resource ecosystem. As they emphasize, previous works have found that plastic foraging promotes community stability, but these did not consider plasticity as an evolving trait, so Ledru et al. set out to test whether this conclusion holds when both plastic foraging and niche traits of consumers and resources evolve (though ultimately, their new conclusions may not all depend on plasticity evolving). Along the way, they first seek to clarify when such plasticity will evolve, and how it affects the evolution of the niche diversity of consumers and resources, before turning to the question of consumer persistence. The model is rather complex, as three traits are allowed to evolve, and the resource uptake expressed through plastic behavior has its own dynamics affected by some form of social learning. Classically, in models of niche evolution, a consumer's efficiency in exploiting a resource characterized by a trait y (here, the resource's individual niche trait), has been described in terms of location-scale (typically Gaussian) kernels, with mean x (the consumer's individual niche trait) specifying the most efficiently exploited resource, and with variance characterizing individual niche breadth. The evolution of the variance has been considered in some previous models but is assumed to be fixed here. Rather, the new model considers the evolution of the distribution of resource traits, of the consumer's individual niche trait (which is not plastic), and of a "plastic foraging trait" that controls the relative time spent foraging plastically versus foraging randomly. When foraging plastically, the consumers modify their foraging effort towards the type of resource that maximizes their energy intake. in some previous models, the effect of variation in the extent of plastic foraging was already considered, but the evolution of allocation to a plastic foraging strategy versus random foraging was not considered. The model is formulated through reaction-diffusion equations, and its dynamics is investigated by numerical integration. Foraging plasticity readily evolves, when resources vary widely enough, competition for resources is strong, and the cost of plasticity is weak. This means in particular that a large individual niche width of consumers selects for increased plastic foraging, as the evolution of plastic foraging leads to reduced niche overlap between consumers. The evolution of plastic foraging itself generally, though not always, favors the diversification of the niche traits of consumers and of resources. There is thus a positive feedback loop between plastic foraging and resource diversity. Ledru et al. conclude that the total niche width of the consumer population should also correlate with the evolution of plastic foraging, an implication which they relate to the so-called niche variation hypothesis and to empirical tests of it. The joint evolution of the consumer's individual niche trait and plastic foraging trait generates a striking pattern within populations: consumers whose individual niche trait is at an edge of the resource distribution forage more plastically. The authors observe that this relatively simple prediction has not been subjected to any empirical test. Returning to the question of consumer persistence, Ledru et al. evaluate this persistence when consumer mortality increases, and in response to either gradual or sudden environmental changes. These different perturbations all reduce the benefits of plastic foraging. The effect of plastic foraging on stability are complex, being negative or positive effect depending on the type of disturbance, and in particular the ecosystem has a lower sustainable rate of environmental change in the presence of plastic foraging. However, allowing the evolutionary regression of plastic foraging then has a comparatively positive effect on persistence. Despite the substantial effort devoted to analyzing this complex model, relaxing some of its assumptions would likely reveal further complexities. Notably, the overall effect of plasticity on consumer persistence depends on effects already encountered in models of the adaptive response of single species to environmental change: a fast non-genetic response in the short term versus a weakened genetic response in the longer term. The overall balance between these opposite effects on adaptation may be difficult to predict robustly. In the case of a constant rate of environmental change, the results of the present model depend on a lag load between the trait changes of consumer and resource populations, and the extent of the lag may also depend on many factors, such as the extent of genetic variation (e.g., Bürger & Lynch, 1995) for niche traits in consumers and resources. Here, the same variance of mutational effects was assumed for all three evolving traits. Further, spatial environmental variation, a central issue in studies of adaptive responses to environmental changes (e.g., Parmesan, 2006, Zhu et al., 2012), was not considered. Finally, the rate of adjustment of effort by consumers with given niche trait and plastic foraging trait values was assumed proportional to the density of consumers with such trait values. This was justified as a way of accounting for the use of social cues during foraging, but to the extent that they occur, social effects could manifest themselves through other learning dynamics. In conclusion, Ledru et al. have addressed a broad range of questions, suggesting new empirical tests of behavioural patterns on one side, and recovering in the context of community response to environmental changes a complexity that could be expected from earlier works on adaptive responses of organisms but that has been overlooked by previous works on community effects of phenotypic plasticity. References Bürger, R. and Lynch, M. (1995), Evolution and extinction in a changing environment: a quantitative-genetic analysis. Evolution, 49: 151-163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1995.tb05967.x Chevin, L.-M., Collins, S. and Lefèvre, F. (2013), Phenotypic plasticity and evolutionary demographic responses to climate change: taking theory out to the field. Funct Ecol, 27: 967-979. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02043.x Duputié, A., Rutschmann, A., Ronce, O. and Chuine, I. (2015), Phenological plasticity will not help all species adapt to climate change. Glob Change Biol, 21: 3062-3073. https://doi-org.inee.bib.cnrs.fr/10.1111/gcb.12914 Ledru, L., Garnier, J., Guillot, O., Faou, E., & Ibanez, S. (2023). The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer model. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2QG7M Parmesan, C. (2006) Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change Vinton, A.C., Gascoigne, S.J.L., Sepil, I., Salguero-Gómez, R., (2022) Plasticity’s role in adaptive evolution depends on environmental change components. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 37: 1067-1078. Zhu, K., Woodall, C.W. and Clark, J.S. (2012), Failure to migrate: lack of tree range expansion in response to climate change. Glob Change Biol, 18: 1042-1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02571.x | The evolutionary dynamics of plastic foraging and its ecological consequences: a resource-consumer model | Léo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Océane Guillot, Erwan Faou, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Ibanez | <p style="text-align: justify;">Phenotypic plasticity has important ecological and evolutionary consequences. In particular, behavioural phenotypic plasticity such as plastic foraging (PF) by consumers, may enhance community stability. Yet little ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | François Rousset | 2023-03-25 12:04:08 | View | |

23 Feb 2024

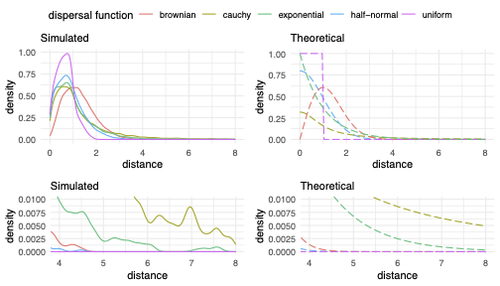

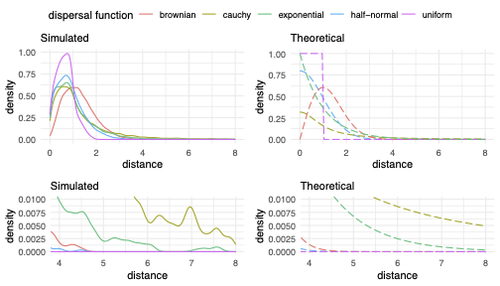

Exploring the effects of ecological parameters on the spatial structure of genetic tree sequencesMariadaria K. Ianni-Ravn, Martin Petr, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.27.534388Disentangling the impact of mating and competition on dispersal patternsRecommended by Diego Ortega-Del Vecchyo based on reviews by Anthony Wilder Wohns, Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewersSpatial population genetics is a field that studies how different evolutionary processes shape geographical patterns of genetic variation. This field is currently hampered by the lack of a deep understanding of the impact of different evolutionary processes shaping the genetic diversity observed across a continuous space (Bradburd and Ralph 2019). Luckily, the recent development of slendr (Petr et al. 2023), which uses the simulator SLiM (Haller and Messer 2023), provides a powerful tool to perform simulations to analyze the impact of different evolutionary parameters on spatial patterns of genetic variation. Here, Ianni-Ravn, Petr, and Racimo 2023 present a series of well-designed simulations to study how three evolutionary factors (dispersal distance, competition distance, and mate choice distance) shape the geographical structure of genealogies. The authors model the dispersal distance between parents and their offspring using five different distributions. Then, the authors perform simulations and they contrast the correspondence between the distribution of observed parent-offspring distances (called DD in the paper) and the distribution used in the simulations (called DF). The authors observe a reasonable correspondence between DF and DD. The authors then show that the competition distance, which decreases the fitness of individuals due to competition for resources if the individuals are close to each other, has small effects on the differences between DD and DF. In contrast, the mate choice distance (which specifies how far away can a parent go to choose a mate) causes discrepancies between DD and DF. When the mate choice distance is small, the individuals tend to cluster close to each other. Overall, these results show that the observed distances between parents and offspring are dependent on the three parameters inspected (dispersal distance, competition distance, and mate choice distance) and make the case that further ecological knowledge of each of these parameters is important to determine the processes driving the dispersal of individuals across geographical space. Based on these results, the authors argue that an “effective dispersal distance” parameter, which takes into account the impact of mate choice distance and dispersal distance, is more prone to be inferred from genetic data. The authors also assess our ability to estimate the dispersal distance using genealogical data in a scenario where the mating distance has small effects on the dispersal distance. Interestingly, the authors show that accurate estimates of the dispersal distance can be obtained when using information from all the parents and offspring going from the present back to the coalescence of all the individuals to the most recent common ancestor. On the other hand, the estimates of the dispersal distance are underestimated when less information from the parent-offspring relationships is used to estimate the dispersal distance. This paper shows the importance of considering mating patterns and the competition for resources when analyzing the dispersal of individuals. The analysis performed by the authors backs up this claim with carefully designed simulations. I recommend this preprint because it makes a strong case for the consideration of ecological factors when analyzing the structure of genealogies and the dispersal of individuals. Hopefully more studies in the future will continue to use simulations and to develop analytical theory to understand the importance of various ecological processes driving spatial genetic variation changes. Bradburd, Gideon S., and Peter L. Ralph. 2019. “Spatial Population Genetics: It’s About Time.” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 50 (1): 427–49. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-022659. Haller, Benjamin C., and Philipp W. Messer. 2023. “SLiM 4: Multispecies Eco-Evolutionary Modeling.” The American Naturalist 201 (5): E127–39. https://doi.org/10.1086/723601. Ianni-Ravn, Mariadaria K., Martin Petr, and Fernando Racimo. 2023. “Exploring the Effects of Ecological Parameters on the Spatial Structure of Genealogies.” bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.27.534388. Petr, Martin, Benjamin C. Haller, Peter L. Ralph, and Fernando Racimo. 2023. “Slendr: A Framework for Spatio-Temporal Population Genomic Simulations on Geographic Landscapes.” Peer Community Journal 3 (e121). https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.354. | Exploring the effects of ecological parameters on the spatial structure of genetic tree sequences | Mariadaria K. Ianni-Ravn, Martin Petr, Fernando Racimo | <p>Geographic space is a fundamental dimension of evolutionary change, determining how individuals disperse and interact with each other. Consequently, space has an important influence on the structure of genealogies and the distribution of geneti... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Diego Ortega-Del Vecchyo | 2023-03-31 18:21:02 | View | |

14 Dec 2023

Genetic sex determination in three closely related hydrothermal vent gastropods, including one species with intersex individualsCastel J, Pradillon F, Cueff V, Leger G, Daguin-Thiébaut C, Ruault S, Mary J, Hourdez S, Jollivet D, and Broquet T https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.11.536409A shared XY sex chromosome system with variable recombination ratesRecommended by Tanja Schwander based on reviews by Hugo Darras, Daniel Jeffries and 1 anonymous reviewerMany species with separate sexes have evolved sex chromosomes, with the sex-limited chromosomes (i.e. the Y or W chromosomes) exhibiting a wide range of genetic divergences from their homologous X or Z chromosomes (Bachtrog et al., 2014). Variable divergences can result from the cessation of recombination between sex chromosomes that occurred at different time points, with the mechanisms of initiation and expansion of recombination suppression along sex chromosomes remaining poorly understood (Charlesworth, 2017). The study by Castel et al (2023) describes the serendipitous discovery of a shared XY sex chromosome system in three closely related hydrothermal vent gastropods. The X and Y chromosomes appear to still recombine but at variable rates across the three species. This variation makes the gastropod system a very promising focus for future research on sex chromosome evolution. An additional intriguing finding is that some females in one of three gastropod species contain male reproductive tissue in their gonads, providing a fascinating case of a mixed or transitory sexual system. Overall, the study by Castel et al (2023) offers the first insights into the reproduction and sex chromosome system of animals living in deep marine vents, which have remained poorly studied and open outstanding research perspectives on these creatures. References Bachtrog, D., J.E.Mank, C.L.Peichel, M.Kirkpatrick, S.P.Otto, T.L. Ashman, M.W.Hahn, J.Kitano, I.Mayrose, R.Ming, et al. 2014.Sex determination: why so many ways of doing it? PLoSBiol. 12:e1001899. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001899 Charlesworth, D. Young sex chromosomes in plants and animals. 2019. New Phytologist 224: 1095–1107. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16002 Castel J, Pradillon F, Cueff V, Leger G, Daguin-Thiébaut C, Ruault S, Mary J, Hourdez S, Jollivet D, and Broquet T 2023. Genetic sex determination in three closely related hydrothermal vent gastropods, including one species with intersex individuals. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.11.536409 | Genetic sex determination in three closely related hydrothermal vent gastropods, including one species with intersex individuals | Castel J, Pradillon F, Cueff V, Leger G, Daguin-Thiébaut C, Ruault S, Mary J, Hourdez S, Jollivet D, and Broquet T | <p style="text-align: justify;">Molluscs have a wide variety of sexual systems and have undergone many transitions from separate sexes to hermaphroditism or vice versa, which is of interest for studying the evolution of sex determination and diffe... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Tanja Schwander | 2023-04-14 11:48:25 | View | |

04 Mar 2024

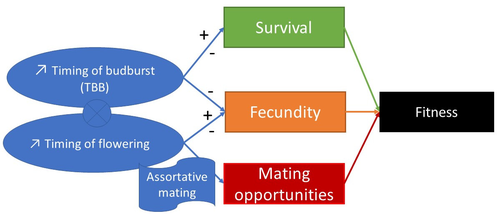

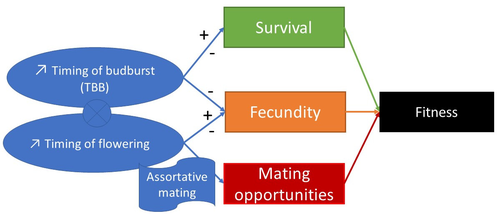

Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.).Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Aurore Bontemps, Julie Gauzere, Etienne Klein https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538521Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.)Recommended by Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Starting with the seminar paper by Lande & Arnold (1983), several studies have addressed phenotypic selection in natural populations of a wide variety of organisms, with a recent renewed interest in forest trees (e.g., Oddou-Muratorio et al. 2018; Alexandre et al. 2020; Westergren et al. 2023). Because of their long generation times, long-lived organisms such as forest trees may suffer the most from maladaptation due to climate change, and whether they will be able to adapt to new environmental conditions in just one or a few generations is hotly debated. In this study, Oddou-Muratorio and colleagues (2024) extend the current framework to add two additional selection components that may alter patterns of fecundity selection and the estimation of standard selection gradients, namely sexual selection (evaluated as differences in flowering phenology conducting to assortative mating) and growth (viability) selection. Notably, the study is conducted in two contrasted environments (low vs high altitude populations) providing information on how the environment may modulate selection patterns in spring phenology. Spring phenology is a key adaptive trait that has been shown to be already affected by climate change in forest trees (Alberto et al. 2013). While fecundity selection for early phenology has been extensively reported before (see Munguía-Rosas et al. 2011), the authors found that this kind of selection can be strongly modulated by sexual selection, depending on the environment. Moreover, they found a significant correlation between early phenology and seedling growth in a common garden, highlighting the importance of this trait for early survival in European beech. As a conclusion, this original research puts in evidence the need for more integrative approaches for the study of natural selection in the field, as well as the importance of testing multiple environments and the relevance of common gardens to further evaluate phenotypic changes due to real-time selection. PS: The recommender and the first author of the preprint have shared authorship in a recent paper in a similar topic (Westergren et al. 2023). Nevertheless, the recommender has not contributed in any way or was aware of the content of the current preprint before acting as recommender, and steps have been taken for a fair and unpartial evaluation. References Alberto, F. J., Aitken, S. N., Alía, R., González‐Martínez, S. C., Hänninen, H., Kremer, A., Lefèvre, F., Lenormand, T., Yeaman, S., Whetten, R., & Savolainen, O. (2013). Potential for evolutionary responses to climate change - evidence from tree populations. Global Change Biology, 19(6), 1645‑1661. Oddou-Muratorio S, Bontemps A, Gauzere J, Klein E (2024) Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). bioRxiv, 2023.04.27.538521, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538521 Oddou-Muratorio, S., Gauzere, J., Bontemps, A., Rey, J.-F., & Klein, E. K. (2018). Tree, sex and size: Ecological determinants of male vs. female fecundity in three Fagus sylvatica stands. Molecular Ecology, 27(15), 3131‑3145. | Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (*Fagus sylvatica* L.). | Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Aurore Bontemps, Julie Gauzere, Etienne Klein | <p>Background: Plant phenological traits such as the timing of budburst or flowering can evolve on ecological timescales through response to fecundity and viability selection. However, interference with sexual selection may arise from assortative ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez | 2023-05-02 11:57:23 | View | |

25 Jan 2024

Sperm production and allocation in response to risk of sperm competition in the black soldier fly Hermetia illucensFrédéric Manas, Carole Labrousse, Christophe Bressac https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.20.544772Elevated sperm production and faster transfer: plastic responses to the risk of sperm competition in males of the black sodier fly Hermetia illuceRecommended by Trine Bilde based on reviews by Rebecca Boulton, Isabel Smallegange and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Rebecca Boulton, Isabel Smallegange and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this paper (Manas et al., 2023), the authors investigate male responses to risk of sperm competition in the black soldier fly Hermetia illuce, a widespread insect that has gained recent attention for its potential to be farmed for sustainable food production (Tomberlin & van Huis, 2020). Using an experimental approach that simulated low-risk (males were kept individually) and high-risk (males were kept in groups of 10) of sperm competition, they found that males reared in groups showed a significant increase in sperm production compared with males reared individually. This shows a response to the rearing environment in sperm production that is consistent with an increase in the perceived risk of sperm competition. These males were then used in mating experiments to determine whether sperm allocation to females during mating was influenced by the perceived risk of sperm competition. Mating experiments were initiated in groups, since mating only occurs when more than one male and one female are present, indicating strong sexual selection in the wild. Once a copulation began, the pair was moved to a new environment with no competition, with male competitors, or with other females, to test how social environment and potentially the sex of surrounding individuals influenced sperm allocation during mating. Copulation duration and the number of sperm transferred were subsequently counted. In these mating experiments, the number of sperm stored in the female spermathecae increased under immediate risk of sperm competition. Interestingly, this was not because males copulated for longer depending on the risk of sperm competition, indicating that males respond plastically to the risk of competition by elevating their investment in sperm production and speed of sperm transfer. There was no difference between competitive environments consisting of males or females respectively, suggesting that it is the presence of other flies per se that influence sperm allocation. The study provides an interesting new example of how males alter reproductive investment in response to social context and sexual competition in their environment. In addition, it provides new insights into the reproductive biology of the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens, which may be relevant for optimizing farming conditions. References Manas F, Labrousse C, Bressac C (2023) Sperm production and allocation in response to risks of sperm competition in the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens. bioRxiv, 2023.06.20.544772, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.20.544772 Tomberlin JK, Van Huis A (2020) Black soldier fly from pest to ‘crown jewel’ of the insects as feed industry: an historical perspective. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 6, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.3920/JIFF2020.0003 | Sperm production and allocation in response to risk of sperm competition in the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens | Frédéric Manas, Carole Labrousse, Christophe Bressac | <p style="text-align: justify;">In polyandrous species, competition between males for offspring paternity goes on after copulation through the competition of their ejaculates for the fertilisation of female's oocytes. Given that males allocating m... | Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Trine Bilde | 2023-06-26 09:41:07 | View | ||

04 Mar 2024

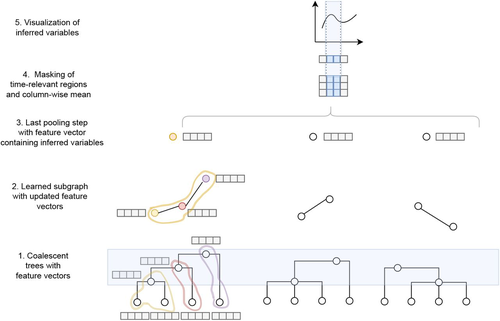

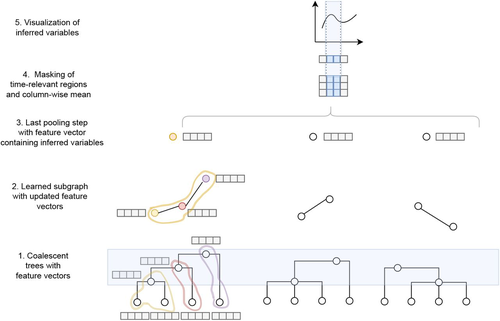

Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta CoalescentKevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.28.508873Beyond the standard coalescent: demographic inference with complete genomes and graph neural networks under the beta coalescentRecommended by Julien Yann Dutheil based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Modelling the evolution of complete genome sequences in populations requires accounting for the recombination process, as a single tree can no longer describe the underlying genealogy. The sequentially Markov coalescent (SMC, McVean and Cardin 2005; Marjoram and Wall 2006) approximates the standard coalescent with recombination process and permits estimating population genetic parameters (e.g., population sizes, recombination rates) using population genomic datasets. As such datasets become available for an increasing number of species, more fine-tuned models are needed to encompass the diversity of life cycles of organisms beyond the model species on which most methods have been benchmarked. The work by Korfmann et al. (Korfmann et al. 2024) represents a significant step forward as it accounts for multiple mergers in SMC models. Multiple merger models account for simultaneous coalescence events so that more than two lineages find a common ancestor in a given generation. This feature is not allowed in standard coalescent models and may result from selection or skewed offspring distributions, conditions likely met by a broad range of species, particularly microbial. Yet, this work goes beyond extending the SMC, as it introduces several methodological innovations. The "classical" SMC-based inference approaches rely on hidden Markov models to compute the likelihood of the data while efficiently integrating over the possible ancestral recombination graphs (ARG). Following other recent works (e.g. Gattepaille et al. 2016), Korfmann et al. propose to separate the ARG inference from model parameter estimation under maximum likelihood (ML). They introduce a procedure where the ARG is first reconstructed from the data and then taken as input in the model fitting step. While this approach does not permit accounting for the uncertainty in the ARG reconstruction (which is typically large), it potentially allows for the extraction of more information from the ARG, such as the occurrence of multiple merging events. Going away from maximum likelihood inference, the authors trained a graph neural network (GNN) on simulated ARGs, introducing a new, flexible way to estimate population genomic parameters. The authors used simulations under a beta-coalescent model with diverse demographic scenarios and showed that the ML and GNN approaches introduced can reliably recover the simulated parameter values. They further show that when the true ARG is given as input, the GNN outperforms the ML approach, demonstrating its promising power as ARG reconstruction methods improve. In particular, they showed that trained GNNs can disentangle the effects of selective sweeps and skewed offspring distributions while inferring past population size changes. This work paves the way for new, exciting applications, though many questions must be answered. How frequent are multiple mergers? As the authors showed that these events "erase" the record of past demographic events, how many genomes are needed to conduct reliable inference, and can the methods computationally cope with the resulting (potentially large) amounts of required data? This is particularly intriguing as micro-organisms, prone to strong selection and skewed offspring distributions, also tend to carry smaller genomes. References Gattepaille L, Günther T, Jakobsson M. 2016. Inferring Past Effective Population Size from Distributions of Coalescent Times. Genetics 204:1191-1206. | Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta Coalescent | Kevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier | <p style="text-align: justify;">The reproductive mechanism of a species is a key driver of genome evolution. The standard Wright-Fisher model for the reproduction of individuals in a population assumes that each individual produces a number of off... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Theory, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics | Julien Yann Dutheil | 2023-07-31 13:11:22 | View | |

02 Feb 2024

Community structure of heritable viruses in a Drosophila-parasitoids complexJulien Varaldi, David Lepetit, Nelly Burlet, Camille Faber, Bérénice Baretje, Roland Allemand https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.29.551099The virome of a Drosophilidae-parasitoid communityRecommended by Ben Longdon based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

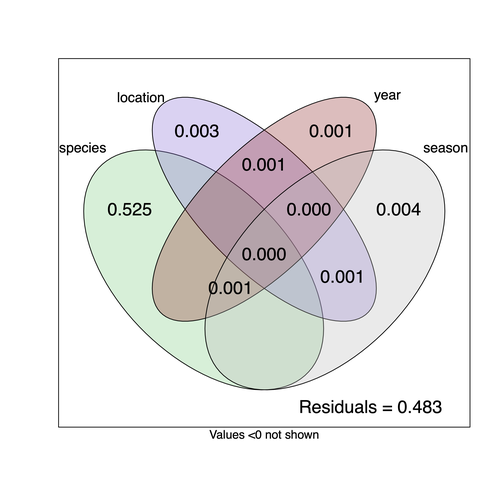

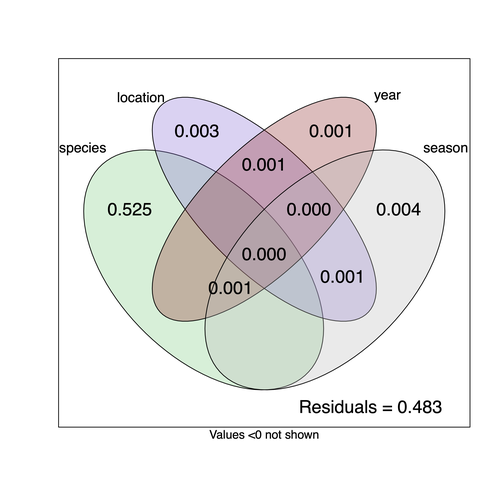

Understanding the factors that shape the virome of a host is key to understanding virus ecology and evolution (Obbard, 2018; French & Holmes, 2020). There is still much to learn about the diversity and distribution of viruses in a host community (Wille et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2023). The viruses of parasitoid wasps are well studied, and their viruses, or integrated viral genes, are known to suppress their insect host’s immune response to enhance parasitoid survival (Herniou et al., 2013; Coffman et al., 2022). Likewise, the insect virome is being increasingly well studied (Shi et al., 2016), with the virome of Drosophila species being particularly well characterised over the best part of the last century (L'Heritier & Teissier, 1937; L'Heritier, 1970; Brun & Plus, 1980; Longdon et al., 2010; Longdon et al., 2011; Longdon et al., 2012; Webster et al., 2015; Webster et al., 2016; Medd et al., 2018; Wallace et al., 2021). However, the viromes of parasitoids and their insect host communities have been less well studied (Leigh et al., 2018; Caldas-Garcia et al., 2023), and the inherent connectivity between parasitoids and their hosts provides an interesting system to study virus host range and cross-species transmission. Here, Varaldi et al (Varaldi et al., 2024) have examined the viruses associated with a community of nine Drosophilidae hosts and six parasitoids. Using both RNA and DNA sequencing of insects reared for two generations, they selected viruses that are maintained in the lab either via vertical transmission or contamination of rearing medium. From 55 pools of insects they found 53 virus-like sequences, 37 of which were novel. Parasitoids were host to nearly twice as many viruses as their Drosophila hosts, although they note this could be due to differences in the rearing temperatures of the hosts. They next quantified if species, year, season, or location played a role in structuring the virome, finding only a significant effect of host species, which explained just over 50% of the variation in virus distribution. No evidence was found of related species sharing more similar virus communities. Although looking at a limited number of species, this suggests that these viruses are not co-speciating or preferentially host switching between closely related species. Finally, they carried out crosses between lines of the parasitoid Leptopilina heterotoma that were infected and uninfected for a novel Iflavirus found in their sequencing data. They found evidence of high levels of maternal transmission and lower level horizontal transmission between wasp larvae parasitising the same host. No evidence of changes in parasitoid-induced mortality, developmental success or the sex ratio was found in iflavirus-infected parasitoids. Interestingly individuals infected with this RNA virus also contained viral DNA, but this did not appear to be integrated into the wasp genome. Overall, this work has taken the first steps in examining the community structure of the virome of parasitoids together with their Drosophilidae hosts. This work will not doubt stimulate follow-up studies to explore the evolution and ecology of these novel virus communities. References Brun G, Plus N (1980) The viruses of Drosophila. In: The genetics and biology of Drosophila eds Ashburner M & Wright TRF), pp. 625-702. Academic Press, New York. | Community structure of heritable viruses in a *Drosophila*-parasitoids complex | Julien Varaldi, David Lepetit, Nelly Burlet, Camille Faber, Bérénice Baretje, Roland Allemand | <p style="text-align: justify;">The diversity and phenotypic impacts related to the presence of heritable bacteria in insects have been extensively studied in the last decades. On the contrary, heritable viruses have been overlooked for several re... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Ben Longdon | 2023-08-03 01:07:43 | View | |

12 Feb 2024

How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks?Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.01.550272How to survive the mutational meltdown: lessons from plant RNA virusesRecommended by Kavita Jain based on reviews by Brent Allman, Ana Morales-Arce and 1 anonymous reviewerAlthough most mutations are deleterious, the strongly deleterious ones do not spread in a very large population as their chance of fixation is very small. Another mechanism via which the deleterious mutations can be eliminated is via recombination or sexual reproduction. However, in a finite asexual population, the subpopulation without any deleterious mutation will eventually acquire a deleterious mutation resulting in the reduction of the population size or in other words, an increase in the genetic drift. This, in turn, will lead the population to acquire deleterious mutations at a faster rate eventually leading to a mutational meltdown. This irreversible (or, at least over some long time scales) accumulation of deleterious mutations is especially relevant to RNA viruses due to their high mutation rate, and while the prior work has dealt with bacteriophages and RNA viruses, the study by Lafforgue et al. [1] makes an interesting contribution to the existing literature by focusing on plants. In this study, the authors enquire how despite the repeated increase in the strength of genetic drift, how the RNA viruses manage to survive in plants. Following a series of experiments and some numerical simulations, the authors find that as expected, after severe bottlenecks, the fitness of the population decreases significantly. But if the bottlenecks are followed by population expansion, the Muller’s ratchet can be halted due to the genetic diversity generated during population growth. They hypothesize this mechanism as a potential way by which the RNA viruses can survive the mutational meltdown. As a theoretician, I find this investigation quite interesting and would like to see more studies addressing, e.g., the minimum population growth rate required to counter the potential extinction for a given bottleneck size and deleterious mutation rate. Of course, it would be interesting to see in future work if the hypothesis in this article can be tested in natural populations. References [1] Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena (2024) How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks? bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology | How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks? | Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena | <p>Muller's ratchet refers to the irreversible accumulation of deleterious mutations in small populations, resulting in a decline in overall fitness. This phenomenon has been extensively observed in experiments involving microorganisms, including ... | Experimental Evolution, Genome Evolution | Kavita Jain | 2023-08-04 09:37:08 | View | ||

28 Mar 2024

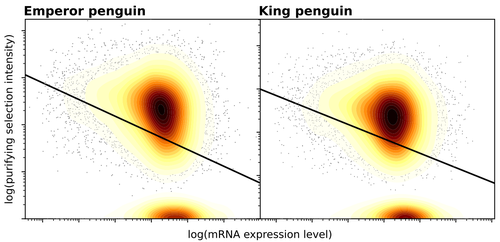

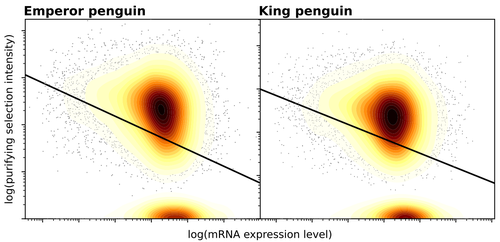

Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populationsEmiliano Trucchi, Piergiorgio Massa, Francesco Giannelli, Thibault Latrille, Flavia A.N. Fernandes, Lorena Ancona, Nils Chr Stenseth, Joan Ferrer Obiol, Josephine Paris, Giorgio Bertorelle, Celine Le Bohec https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552445Purifying selection on highly expressed genes in PenguinsRecommended by Bruce Rannala based on reviews by Tanja Pyhäjärvi and 1 anonymous reviewerGiven the general importance of protein expression levels, in cells it is widely accepted that gene expression levels are often a target of natural selection and that most mutations affecting gene expression levels are therefore likely to be deleterious [1]. However, it is perhaps less obvious that the strength of selection on the regulated genes themselves may be influenced by their expression levels. This might be due to harmful effects of misfolded proteins, for example, when higher protein concentrations exist in cells [2]. Recent studies have suggested that highly expressed genes accumulate fewer deleterious mutations; thus a positive relationship appears to exist between gene expression levels and the relative strength of purifying selection [3]. The recommended paper by Trucchi et al. [4] examines the relationship between gene expression, purifying selection and a third variable -- effective population size -- in populations of two species of penguin with different population sizes, the Emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) and the King penguin (A. patagonicus). Using transcriptomic data and computer simulations modeling selection, they examine patterns of nonsynonymous and synonymous segregating polymorphisms (p) across genes in the two populations, concluding that even in relatively small populations purifying selection has an important effect in eliminating deleterious mutations. References 1] Gilad Y, Oshlack A, and Rifkin SA. 2006. Natural selection on gene expression. Trends in Genetics 22: 456-461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.002 [4] Trucchi E, Massa P, Giannelli F, Latrille T, Fernandes FAN, Ancona L, Stenseth NC, Obiol JF, Paris J, Bertorelle G, and Le Bohec, C. 2023. Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populations. bioRxiv 2023.08.08.552445, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552445

| Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populations | Emiliano Trucchi, Piergiorgio Massa, Francesco Giannelli, Thibault Latrille, Flavia A.N. Fernandes, Lorena Ancona, Nils Chr Stenseth, Joan Ferrer Obiol, Josephine Paris, Giorgio Bertorelle, Celine Le Bohec | <p style="text-align: justify;">Purifying selection is the most pervasive type of selection, as it constantly removes deleterious mutations arising in populations, directly scaling with population size. Highly expressed genes appear to accumulate ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Bruce Rannala | 2023-08-09 17:53:03 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer