Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors▲ | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

05 Oct 2017

Using Connectivity To Identify Climatic Drivers Of Local AdaptationStewart L. Macdonald, John Llewelyn, Ben Phillips 10.1101/145169A new approach to identifying drivers of local adaptationRecommended by Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer based on reviews by Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer and Thomas LenormandLocal adaptation, the higher fitness a population achieves in its local “home” environment relative to other environments is a crucial phase in the divergence of populations, and as such both generates and maintains diversity. Local adaptation is enhanced by selection and genetic variation in the relevant traits, and decreased by gene flow and genetic drift. Demonstrating local adaptation is laborious, and is typically done with a reciprocal transplant design [1], documenting repeated geographic clines [e.g. 2, 3] also provides strong evidence of local adaptation. Even when well documented, it is often unknown which aspects of the environment impose selection. Indeed, differences in environment between different sites that are measured during studies of local adaptation explain little of the variance in the degree of local adaptation [4]. This poses a problem to population management. Given climate change and habitat destruction, understanding the environmental drivers of local adaptation can be crucially important to conducting successful assisted migration or targeted gene flow. In this manuscript, Macdonald et al. [5] propose a means of identifying which aspects of the environment select for local adaptation without conducting a reciprocal transplant experiment. The idea is that the strength of relationships between traits and environmental variables that are due to plastic responses to the environment will not be influenced by gene flow, but the strength of trait-environment relationships that are due to local adaptation should decrease with gene flow. This then can be used to reduce the somewhat arbitrary list of environmental variables on which data are available down to a targeted list more likely to drive local adaptation in specific traits. To perform such an analysis requires three things: 1) measurements of traits of interest in a species across locations, 2) an estimate of gene flow between locations, which can be replaced with a biologically meaningful estimate of how well connected those locations are from the point of view of the study species, and 3) data on climate and other environmental variables from across a species’ range, many of which are available on line. Macdonald et al. [5] demonstrate their approach using a skink (Lampropholis coggeri). They collected morphological and physiological data on individuals from multiple populations. They estimated connectivity among those locations using information on habitat suitability and dispersal potential [6], and gleaned climatic data from available databases and the literature. They find that two physiological traits, the critical minimum and maximum temperatures, show the strongest signs of local adaptation, specifically local adaptation to annual mean precipitation, precipitation of the driest quarter, and minimum annual temperature. These are then aspects of skink phenotype and skink habitats that could be explored further, or could be used to provide background information if migration efforts, for example for genetic rescue [7] were initiated. The approach laid out has the potential to spark a novel genre of research on local adaptation. It its simplest form, knowing that local adaptation is eroded by gene flow, it is intuitive to consider that if connectivity reduces the strength of the relationship between an environmental variable and a trait, that the trait might be involved in local adaptation. The approach is less intuitive than that, however – it relies not connectivity per-se, but the interaction between connectivity and different environmental variables and how that interaction alters trait-environment relationships. The authors lay out a number of useful caveats and potential areas that could use further development. It will be interesting to see how the community of evolutionary biologists responds. References [1] Blanquart F, Kaltz O, Nuismer SL and Gandon S. 2013. A practical guide to measuring local adaptation. Ecology Letters, 16: 1195-1205. doi: 10.1111/ele.12150 [2] Huey RB, Gilchrist GW, Carlson ML, Berrigan D and Serra L. 2000. Rapid evolution of a geographic cline in size in an introduced fly. Science, 287: 308-309. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.308 [3] Milesi P, Lenormand T, Lagneau C, Weill M and Labbé P. 2016. Relating fitness to long-term environmental variations in natura. Molecular Ecology, 25: 5483-5499. doi: 10.1111/mec.13855 [4] Hereford, J. 2009. A quantitative survey of local adaptation and fitness trade-offs. The American Naturalist 173: 579-588. doi: 10.1086/597611 [5] Macdonald SL, Llewelyn J and Phillips BL. 2017. Using connectivity to identify climatic drivers of local adaptation. bioRxiv, ver. 4 of October 4, 2017. doi: 10.1101/145169 [6] Macdonald SL, Llewelyn J, Moritz C and Phillips BL. 2017. Peripheral isolates as sources of adaptive diversity under climate change. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 5:88. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2017.00088 [7] Whiteley AR, Fitzpatrick SW, Funk WC and Tallmon DA. 2015. Genetic rescue to the rescue. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30: 42-49. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.10.009 | Using Connectivity To Identify Climatic Drivers Of Local Adaptation | Stewart L. Macdonald, John Llewelyn, Ben Phillips | Despite being able to conclusively demonstrate local adaptation, we are still often unable to objectively determine the climatic drivers of local adaptation. Given the rapid rate of global change, understanding the climatic drivers of local adapta... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications | Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer | Thomas Lenormand | 2017-06-06 13:06:54 | View |

31 Jan 2018

Identifying drivers of parallel evolution: A regression model approachSusan F Bailey, Qianyun Guo, Thomas Bataillon https://doi.org/10.1101/118695A new statistical tool to identify the determinant of parallel evolutionRecommended by Stephanie Bedhomme based on reviews by Bastien Boussau and 1 anonymous reviewerIn experimental evolution followed by whole genome resequencing, parallel evolution, defined as the increase in frequency of identical changes in independent populations adapting to the same environment, is often considered as the product of similar selection pressures and the parallel changes are interpreted as adaptive. References [1] Bailey SF, Guo Q and Bataillon T (2018) Identifying drivers of parallel evolution: A regression model approach. bioRxiv 118695, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/118695 [2] Lang GI, Rice DP, Hickman, MJ, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Botstein D, and Desai MM (2013) Pervasive genetic hitchhiking and clonal interference in forty evolving yeast populations. Nature 500: 571–574. doi: 10.1038/nature12344 | Identifying drivers of parallel evolution: A regression model approach | Susan F Bailey, Qianyun Guo, Thomas Bataillon | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (http://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100045). Parallel evolution, defined as identical changes arising in independent populations, is often attributed... |  | Experimental Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Stephanie Bedhomme | 2017-03-22 14:54:48 | View | |

12 Jun 2017

Modelling the evolution of how vector-borne parasites manipulate the vector's host choiceRecommended by Samuel Alizon based on reviews by Samuel Alizon and Nicole Mideo based on reviews by Samuel Alizon and Nicole Mideo

Many parasites can manipulate their hosts, thus increasing their transmission to new hosts [1]. This is particularly the case for vector-borne parasites, which can alter the feeding behaviour of their hosts. However, predicting the optimal strategy is not straightforward because three actors are involved and the interests of the parasite may conflict with that of the vector. There are few models that consider the evolution of host manipulation by parasites [but see 2-4], but there are virtually none that investigated how parasites can manipulate the host choice of vectors. Even on the empirical side, many aspects of this choice remain unknown. Gandon [5] develops a simple evolutionary epidemiology model that allows him to formulate clear and testable predictions. These depend on which actor controls the trait (the vector or the parasite) and, when there is manipulation, whether it is realised via infected hosts (to attract vectors) or infected vectors (to change host choice). In addition to clarifying the big picture, Gandon [5] identifies some nice properties of the model, for instance an independence of the density/frequency-dependent transmission assumption or a backward bifurcation at R0=1, which suggests that parasites could persist even if their R0 is driven below unity. Overall, this study calls for further investigation of the different scenarios with more detailed models and experimental validation of general predictions. References [1] Hughes D, Brodeur J, Thomas F. 2012. Host manipulation by parasites. Oxford University Press. [2] Brown SP. 1999. Cooperation and conflict in host-manipulating parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 266: 1899–1904. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0864 [3] Lion S, van Baalen M, Wilson WG. 2006. The evolution of parasite manipulation of host dispersal. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 273: 1063–1071. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3412 [4] Vickery WL, Poulin R. 2010. The evolution of host manipulation by parasites: a game theory analysis. Evolutionary Ecology 24: 773–788. doi: 10.1007/s10682-009-9334-0 [5] Gandon S. 2017. Evolution and manipulation of vector host choice. bioRxiv 110577, ver. 3 of 7th June 2017. doi: 10.1101/110577 | Evolution and manipulation of vector host choice | Sylvain Gandon | The transmission of many animal and plant diseases relies on the behavior of arthropod vectors. In particular, the choice to feed on either infected or uninfected hosts can dramatically affect the epidemiology of vector-borne diseases. I develop a... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Samuel Alizon | 2017-03-03 19:18:54 | View | |

04 Mar 2024

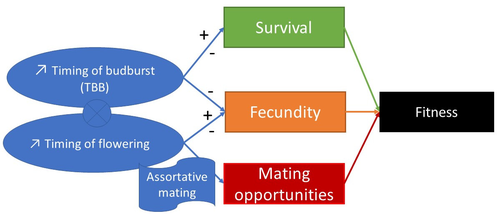

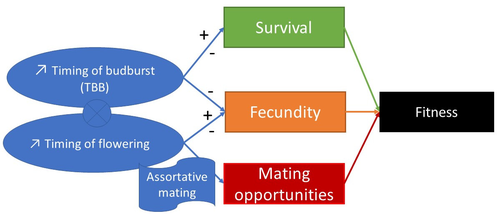

Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.).Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Aurore Bontemps, Julie Gauzere, Etienne Klein https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538521Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.)Recommended by Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Starting with the seminar paper by Lande & Arnold (1983), several studies have addressed phenotypic selection in natural populations of a wide variety of organisms, with a recent renewed interest in forest trees (e.g., Oddou-Muratorio et al. 2018; Alexandre et al. 2020; Westergren et al. 2023). Because of their long generation times, long-lived organisms such as forest trees may suffer the most from maladaptation due to climate change, and whether they will be able to adapt to new environmental conditions in just one or a few generations is hotly debated. In this study, Oddou-Muratorio and colleagues (2024) extend the current framework to add two additional selection components that may alter patterns of fecundity selection and the estimation of standard selection gradients, namely sexual selection (evaluated as differences in flowering phenology conducting to assortative mating) and growth (viability) selection. Notably, the study is conducted in two contrasted environments (low vs high altitude populations) providing information on how the environment may modulate selection patterns in spring phenology. Spring phenology is a key adaptive trait that has been shown to be already affected by climate change in forest trees (Alberto et al. 2013). While fecundity selection for early phenology has been extensively reported before (see Munguía-Rosas et al. 2011), the authors found that this kind of selection can be strongly modulated by sexual selection, depending on the environment. Moreover, they found a significant correlation between early phenology and seedling growth in a common garden, highlighting the importance of this trait for early survival in European beech. As a conclusion, this original research puts in evidence the need for more integrative approaches for the study of natural selection in the field, as well as the importance of testing multiple environments and the relevance of common gardens to further evaluate phenotypic changes due to real-time selection. PS: The recommender and the first author of the preprint have shared authorship in a recent paper in a similar topic (Westergren et al. 2023). Nevertheless, the recommender has not contributed in any way or was aware of the content of the current preprint before acting as recommender, and steps have been taken for a fair and unpartial evaluation. References Alberto, F. J., Aitken, S. N., Alía, R., González‐Martínez, S. C., Hänninen, H., Kremer, A., Lefèvre, F., Lenormand, T., Yeaman, S., Whetten, R., & Savolainen, O. (2013). Potential for evolutionary responses to climate change - evidence from tree populations. Global Change Biology, 19(6), 1645‑1661. Oddou-Muratorio S, Bontemps A, Gauzere J, Klein E (2024) Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). bioRxiv, 2023.04.27.538521, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538521 Oddou-Muratorio, S., Gauzere, J., Bontemps, A., Rey, J.-F., & Klein, E. K. (2018). Tree, sex and size: Ecological determinants of male vs. female fecundity in three Fagus sylvatica stands. Molecular Ecology, 27(15), 3131‑3145. | Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (*Fagus sylvatica* L.). | Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Aurore Bontemps, Julie Gauzere, Etienne Klein | <p>Background: Plant phenological traits such as the timing of budburst or flowering can evolve on ecological timescales through response to fecundity and viability selection. However, interference with sexual selection may arise from assortative ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez | 2023-05-02 11:57:23 | View | |

11 Jun 2019

A bird’s white-eye view on neosex chromosome evolutionThibault Leroy, Yoann Anselmetti, Marie-Ka Tilak, Sèverine Bérard, Laura Csukonyi, Maëva Gabrielli, Céline Scornavacca, Borja Milá, Christophe Thébaud, Benoit Nabholz https://doi.org/10.1101/505610Young sex chromosomes discovered in white-eye birdsRecommended by Kateryna Makova based on reviews by Gabriel Marais, Melissa Wilson and 1 anonymous reviewerRecent advances in next-generation sequencing are allowing us to uncover the evolution of sex chromosomes in non-model organisms. This study [1] represents an example of this application to birds of two Sylvioidea species from the genus Zosterops (commonly known as white-eyes). The study is exemplary in the amount and types of data generated and in the thoroughness of the analysis applied. Both male and female genomes were sequenced to allow the authors to identify sex-chromosome specific scaffolds. These data were augmented by generating the transcriptome (RNA-seq) data set. The findings after the analysis of these extensive data are intriguing: neoZ and neoW chromosome scaffolds and their breakpoints were identified. Novel sex chromosome formation appears to be accompanied by translocation events. The timing of formation of novel sex chromosomes was identified using molecular dating and appears to be relatively recent. Yet first signatures of distinct evolutionary patterns of sex chromosomes vs. autosomes could be already identified. These include the accumulation of transposable elements and changes in GC content. The changes in GC content could be explained by biased gene conversion and altered recombination landscape of the neo sex chromosomes. The authors also study divergence and diversity of genes located on the neo sex chromosomes. Here their findings appear to be surprising and need further exploration. The neoW chromosome already shows unique patterns of divergence and diversity at protein-coding genes as compared with genes on either neoZ or autosomes. In contrast, the genes on the neoZ chromosome do not display divergence or diversity patterns different from those for autosomes. This last observation is puzzling and I believe should be explored in further studies. Overall, this study significantly advances our knowledge of the early stages of sex chromosome evolution in vertebrates, provides an example of how such a study could be conducted in other non-model organisms, and provides several avenues for future work. References [1] Leroy T., Anselmetti A., Tilak M.K., Bérard S., Csukonyi L., Gabrielli M., Scornavacca C., Milá B., Thébaud C. and Nabholz B. (2019). A bird’s white-eye view on neo-sex chromosome evolution. bioRxiv, 505610, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/505610 | A bird’s white-eye view on neosex chromosome evolution | Thibault Leroy, Yoann Anselmetti, Marie-Ka Tilak, Sèverine Bérard, Laura Csukonyi, Maëva Gabrielli, Céline Scornavacca, Borja Milá, Christophe Thébaud, Benoit Nabholz | <p>Chromosomal organization is relatively stable among avian species, especially with regards to sex chromosomes. Members of the large Sylvioidea clade however have a pair of neo-sex chromosomes which is unique to this clade and originate from a p... |  | Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Kateryna Makova | 2019-01-24 14:17:15 | View | |

12 Nov 2020

Limits and Convergence properties of the Sequentially Markovian CoalescentThibaut Sellinger, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.23.217091Review and Assessment of Performance of Genomic Inference Methods based on the Sequentially Markovian CoalescentRecommended by Stephan Schiffels based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

The human genome not only encodes for biological functions and for what makes us human, it also encodes the population history of our ancestors. Changes in past population sizes, for example, affect the distribution of times to the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of genomic segments, which in turn can be inferred by sophisticated modelling along the genome. References [1] Li, H., and Durbin, R. (2011). Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature, 475(7357), 493-496. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10231 | Limits and Convergence properties of the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent | Thibaut Sellinger, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier | <p>Many methods based on the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (SMC) have been and are being developed. These methods make use of genome sequence data to uncover population demographic history. More recently, new methods have extended the original... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics | Stephan Schiffels | Anonymous | 2020-07-25 10:54:48 | View |

16 May 2023

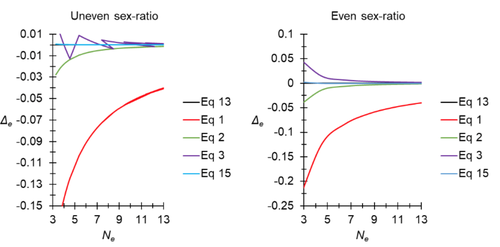

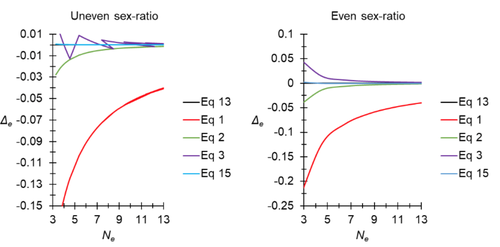

A new and almost perfectly accurate approximation of the eigenvalue effective population size of a dioecious population: comparisons with other estimates and detailed proofsThierry de Meeûs and Camille Noûs https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7927968All you ever wanted to know about Ne in one handy placeRecommended by Charles Baer based on reviews by Jesse ("Jay") Taylor and 1 anonymous reviewerOf the four evolutionary forces, three can be straightforwardly summarized both conceptually and mathematically in the context of an allele at a genomic locus. Mutation (the mutation rate, μ) is simply captured by the per-site, per-generation probability that an allele mutates into a different allele. Recombination (the recombination rate, r) is captured as the probability of recombination between two sites, wherein alleles that are in different genomes in one generation come together in the same genome in the next generation. Natural selection (the selection coefficient, s) is captured by the probability that an allele is present in the next generation, relative to some reference. Random genetic drift – the random fluctuation in allele frequency due to sampling in a finite population - is not so straightforwardly summarized. The first, and most common way of characterizing evolutionary dynamics in a finite population is the Wright-Fisher model, in which the only deviation from the assumptions of Hardy-Weinberg conditions is finite population size. Importantly, in a W-F population, mating between diploid individuals is random, which implies self-fertile monoecy, and generations are non-overlapping. In an ideal W-F population, the probability that a gene copy leaves i descendants in the next generation is the result of binomial sampling of uniting gametes (if the locus is biallelic). The – and the next word is meaningful – magnitude/strength/rate/power/amount of genetic drift is proportional to 1/2N, where N is the size of the population. All of the following are affected by genetic drift: (1) the probability that a neutral allele ultimately reaches fixation, (2) the rate of loss of genetic variation within a population, (3) the rate of increase of genetic variance among populations, (4) the amount of genetic variation segregating in a population, (5) the probability of fixation/loss of a weakly selected variant. Presumably no real population adheres to ideal W-F conditions, which leads to the notion of "effective population size", Ne (Wright 1931), loosely defined as "the size of an ideal W-F population that experiences an equivalent strength of genetic drift". Almost always, Ne<N, and any violation of W-F assumptions can affect Ne. Importantly, Ne can be defined in different ways, and the specific formulation of Ne can have different implications for evolution. Ne was initially defined in terms of the rate of decrease of heterozygosity (inbreeding effective size) and increase in variance among populations (variance effective size). Ewens (1979) defined the Eigenvalue effective size (equivalent to the "random extinction" effective size) and elaborated on the conditions under which the various formulations of Ne differ (Ewens 1982). Nordborg and Krone (2002) defined the effective size in terms of the coalescent, and they identified conditions in which genetic drift cannot be described in terms of a W-F model (Sjodin et al. 2005); also see Karasov et al. (2010); Neher and Shraiman (2011). Distinct from the issue of defining Ne is the issue of calculating Ne from data, which is the focus of this paper by De Meeus and Noûs (2023). Pudovkin et al. (1996) showed that the Eigenvalue effective size in a dioecious population can be formulated in terms of excess heterozygosity, which the current authors note is equivalent to formulating Ne in terms of Wright's FIS statistic. As emphasized by the title, the marquee contribution of this paper is to provide a better approximation of the Eigenvalue effective size in a dioecious population. Science marches onward, although the empirical utility of this advance is obviously limited, given the tremendous inherent sources of uncertainty in real-world estimates of Ne. Perhaps more valuable, however, is the extensive set of appendixes, in which detailed derivations are provided for the various formulations of effective size. By way of analogy, the material presented here can be thought of as an extension of the material presented in section 7.6 of Crow and Kimura (1970), in which the Inbreeding and Variance effective population sizes are derived and compared. The appendixes should serve as a handy go-to source of detailed theoretical information with respect to the different formulations of effective population size. REFERENCES Crow, J. F. and M. Kimura. 1970. An Introduction to Population Genetics Theory. The Blackburn Press, Caldwell, NJ. De Meeûs, T. and Noûs, C. 2023. A new and almost perfectly accurate approximation of the eigenvalue effective population size of a dioecious population: comparisons with other estimates and detailed proofs. Zenodo, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7927968 Ewens, W. J. 1979. Mathematical Population Genetics. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. Ewens, W. J. 1982. On the concept of the effective population size. Theoretical Population Biology 21:373-378. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(82)90024-7 Karasov, T., P. W. Messer, and D. A. Petrov. 2010. Evidence that adaptation in Drosophila Is not limited by mutation at single sites. Plos Genetics 6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000924 Neher, R. A. and B. I. Shraiman. 2011. Genetic Draft and Quasi-Neutrality in Large Facultatively Sexual Populations. Genetics 188:975-U370. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.111.128876 Nordborg, M. and S. M. Krone. 2002. Separation of time scales and convergence to the coalescent in structured populations. Pp. 194–232 in M. Slatkin, and M. Veuille, eds. Modern Developments in Theoretical Population Genetics: The Legacy of Gustave Malécot. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://www.webpages.uidaho.edu/~krone/malecot.pdf Pudovkin, A. I., D. V. Zaykin, and D. Hedgecock. 1996. On the potential for estimating the effective number of breeders from heterozygote-excess in progeny. Genetics 144:383-387. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/144.1.383 Sjodin, P., I. Kaj, S. Krone, M. Lascoux, and M. Nordborg. 2005. On the meaning and existence of an effective population size. Genetics 169:1061-1070. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.104.026799 Wright, S. 1931. Evolution in Mendelian populations. Genetics 16:0097-0159. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/16.2.97 | A new and almost perfectly accurate approximation of the eigenvalue effective population size of a dioecious population: comparisons with other estimates and detailed proofs | Thierry de Meeûs and Camille Noûs | <p>The effective population size is an important concept in population genetics. It corresponds to a measure of the speed at which genetic drift affects a given population. Moreover, this is most of the time the only kind of population size that e... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Charles Baer | 2023-02-22 16:53:49 | View | |

13 Sep 2019

Deceptive combined effects of short allele dominance and stuttering: an example with Ixodes scapularis, the main vector of Lyme disease in the U.S.A.Thierry De Meeûs, Cynthia T. Chan, John M. Ludwig, Jean I. Tsao, Jaymin Patel, Jigar Bhagatwala, and Lorenza Beati https://doi.org/10.1101/622373New curation method for microsatellite markers improves population genetics analysesRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by Eric Petit, Martin Husemann and 2 anonymous reviewersGenetic markers are used for in modern population genetics/genomics to uncover the past neutral and selective history of population and species. Besides Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) obtained from whole genome data, microsatellites (or Short Tandem Repeats, SSR) have been common markers of choice in numerous population genetics studies of non-model species with large sample sizes [1]. Microsatellites can be used to uncover and draw inference of the past population demography (e.g. expansion, decline, bottlenecks…), population split, population structure and gene flow, but also life history traits and modes of reproduction (e.g. [2,3]). These markers are widely used in conservation genetics [4] or to study parasites or disease vectors [5]. Microsatellites do show higher mutation rate than SNPs increasing, on the one hand, the statistical power to infer recent events (for example crop domestication, [2,3]), while, on the other hand, decreasing their statistical power over longer time scales due to homoplasy [6]. References [1] Jarne, P., and Lagoda, P. J. (1996). Microsatellites, from molecules to populations and back. Trends in ecology & evolution, 11(10), 424-429. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)10049-5 | Deceptive combined effects of short allele dominance and stuttering: an example with Ixodes scapularis, the main vector of Lyme disease in the U.S.A. | Thierry De Meeûs, Cynthia T. Chan, John M. Ludwig, Jean I. Tsao, Jaymin Patel, Jigar Bhagatwala, and Lorenza Beati | <p>Null alleles, short allele dominance (SAD), and stuttering increase the perceived relative inbreeding of individuals and subpopulations as measured by Wright’s FIS and FST. Ascertainment bias, due to such amplifying problems are usually caused ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Other, Population Genetics / Genomics | Aurelien Tellier | 2019-05-02 20:52:08 | View | |

13 Nov 2023

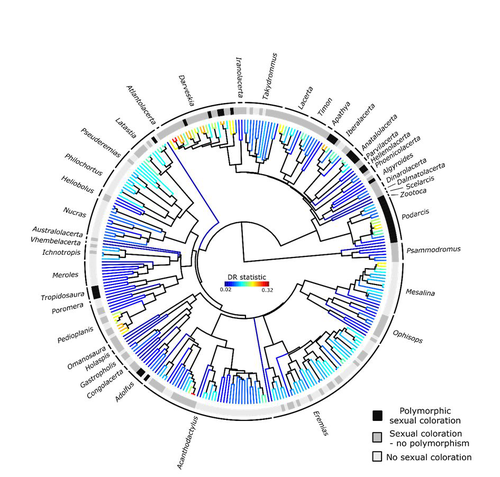

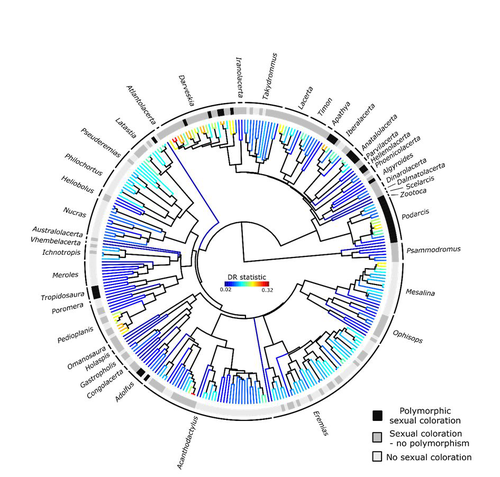

Color polymorphism and conspicuousness do not increase speciation rates in LacertidsThomas de Solan, Barry Sinervo, Philippe Geniez, Patrice David, Pierre-André Crochet https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.15.528678Colour polymorphism does not increase diversification rates in lizardsRecommended by Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe striking differences in species richness among lineages in the Tree of Life have long attracted much research interest. In particular, researchers have asked whether certain traits are associated with greater diversification, with a particular focus on traits under sexual selection given their direct link to mating isolation. Polymorphism, defined as the presence of co-occurring, heritable morphs within a population, has been proposed to influence diversification rates although the effect has been proposed as both promoting or alternatively impeding speciation. The effect of polymorphism may be positive, that is facilitating speciation if polymorphism allows to broaden the ecological niche, thus enabling range expansion, or enabling maintenance of populations in variable environments. Specialized ectomorphs have been observed in several species (e.g. Kusche et al. 2015, Lattanzio and Miles 2016, Whitney et al. 2018, Scali et al. 2016). Polymorphism may also facilitate speciation if a morph is lost during the colonization of a novel area or niche, resulting in rapid divergence of the remaining morphs and reproductive isolation from the ancestral population, known as the morph speciation hypothesis (West-Eberhard 1986, Corl et al. 2010). On the other hand, polymorphism may hamper speciation through disassortative maintaining by morph, which may maintain the polymorphism through the speciation process (Jamie and Meier 2020). An example of such a process is Heliconius numata where disassortative mate preferences based on color hampers ecological speciation (Chouteau et al. 2017). Previous evidence in birds and lizards suggests polymorphism favors diversification (Corl et al. 2010b, 2012, Hugall and Stuart-Fox 2012, Brock et al. 2021). Here, de Solan et al. (2023) test the effect of polymorphism on diversification in Lacertidae, a family of lizards containing more than 300 species distributed across Europe, Africa and Asia. The group offers a good model system to test the effect of polymorphism on speciation as it contains several species with colour polymorphism, sometimes present in both sexes but restricted to males when present in the flank. Using coloration data from the literature as well as photographs of live specimens for 295 species the authors tested whether the presence of polymorphism is associated with higher diversification rates. While undertaking their project, another group independently tackled the same question (Brock et al. 2021), using the same model system but coming to very different conclusions. Therefore, de Solan et al. (2023) decided to also contrast their results with those of Brock et al. (2021) to determine the factors responsible for the contrasting results of both studies. The latter I consider one of the strengths of the work, given the careful re-analyses to determine the causes of the discrepancies between both studies. De Solan et al. (2023) found no association between the presence of polymorphism and diversification rates, even though they used different analytical approaches. Thus, this study is interesting as it provides results that do not support a positive effect of polymorphism on species richness. The use of a phylogeny with more limited species sampling (García-Porta et al. 2019) implied that the authors had to manually add 75 species, of which 17 were added to the tree based on information from previously published trees and 68 were added at random locations within the genus. To control for potential biases the authors repeated the analyses using a sample of trees with the imputed taxa, results were broadly concordant across the set of trees. The careful re-analysis contrasting Brock et al. (2021) and de Solan et al. (2023) results suggests the difference is mainly due to a difference in how species were coded as presenting polymorphism, which differed between the two studies, as well as a difference in the package version used to run the state-dependent diversification models. Interestingly non-parametric analyses yielded similar results across both datasets. Garcia-Porta, J., Irisarri, I., Kirchner, M. et al. 2019. Environmental temperatures shape thermal physiology as well as diversification and genome-wide substitution rates in lizards. Nature Communications. 10: 4077. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11943-x de Solan T, Sinervo B, Geniez P, David P, Crochet P-A (2023) Colour polymorphism and conspicuousness do not increase speciation rates in Lacertids. bioRxiv, 2023.02.15.528678, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.15.528678 West-Eberhard, M.J. 1986. Alternative adaptations, speciation, and phylogeny (A review). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 83: 1388-1392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.83.5.1388 | Color polymorphism and conspicuousness do not increase speciation rates in Lacertids | Thomas de Solan, Barry Sinervo, Philippe Geniez, Patrice David, Pierre-André Crochet | <p style="text-align: justify;">Conspicuous body colors and color polymorphism have been hypothesized to increase rates of speciation. Conspicuous colors are evolutionary labile, and often involved in intraspecific sexual signaling and thus may pr... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Speciation | Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer | 2023-02-22 10:05:03 | View | |

06 Feb 2024

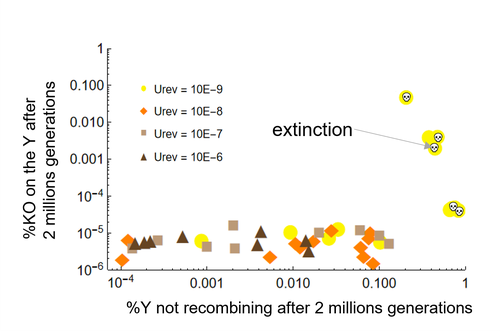

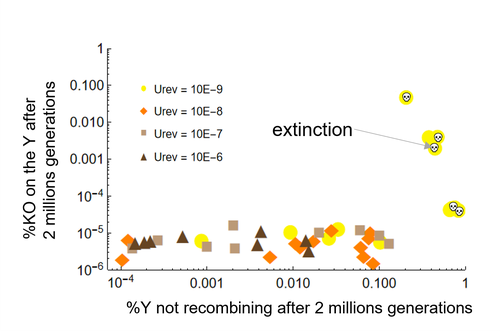

Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes?Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.17.528909New modelling results help understanding the evolution and maintenance of recombination suppression involving sex chromosomesRecommended by Jos Käfer based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersDespite advances in genomic research, many views of genome evolution are still based on what we know from a handful of species, such as humans. This also applies to our knowledge of sex chromosomes. We've apparently been too much used to the situation in which a highly degenerate Y chromosome coexists with an almost normal X chromosome to be able to fully grasp all the questions implied by this situation. Lately, many more sex chromosomes have been studied in other organisms, such as in plants, and the view is changing radically: there is a large diversity of situations, ranging from young highly divergent sex chromosomes to old ones that are so similar that they're hard to detect. Undoubtedly inspired by these recent findings, a few theoretical studies have been published around 2 years ago that put an entirely new light on the evolution of sex chromosomes. The differences between these models have however remained somewhat difficult to appreciate by non-specialists. In particular, the models by Lenormand & Roze (2022) and by Jay et al. (2022) seemed quite similar. Indeed, both rely on the same mechanism for initial recombination suppression: a ``lucky'' inversion, i.e. one with less deleterious mutations than the population average, encompassing the sex-determination locus, is initially selected. However, as it doesn't recombine, it will quickly accumulate deleterious mutations lowering its fitness. And it's at this point the models diverge: according to Lenormand & Roze (2022), nascent dosage compensation not only limits the deleterious effects on fitness by the ongoing degeneration, but it actually opposes recombination restoration as this would lead gene expression away from the optimum that has been reached. On the other hand, in the model by Jay et al. (2022), no additional ingredient is required: they argue that once an inversion had been fixed, reversions that restore recombination are extremely unlikely. This is what Lenormand & Roze (2024) now call a ``constraint'': in Jay et al.'s model, recombination restoration is impossible for mechanistic reasons. Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue such constraints cannot explain long-term recombination suppression. Instead, a mechanism should evolve to limit the negative fitness effects of recombination arrest, otherwise recombination is either restored, or the population goes extinct due to a dramatic drop in the fitness of the heterogametic sex. These two arguments work together: given the huge fitness cost of the lack of ongoing degeneration of the non-recombining Y, in the absence of compensatory mechanisms, there is a very strong selection for the restoration of recombination, so that even when restoration a priori is orders of magnitude less likely than inversion (leading to recombination suppression), it will eventually happen. One way the negative fitness effects of recombination suppression can be limited, is the way the authors propose in their own model: dosage compensation evolves through regulatory evolution right at the start of recombination suppression. This changes our classical, simplistic view that dosage compensation evolves in response to degeneration: rather, Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue, that degeneration can only happen when dosage compensation is effective. The reasoning is convincing and exposes the difference between the models to readers without a firm background in mathematical modelling. Although Lenormand & Roze (2024) target the "constraint theory", it seems likely that other theories for the maintenance of recombination suppression that don't imply the compensation of early degeneration are subject to the same criticism. Indeed, they mention the widely-cited "sexual antagonism" theory, in which mutations with a positive effect in males but a negative in females will select for recombination suppression that will link them to the sex-determining gene on the Y. However, once degeneration starts, the sexually-antagonistic benefits should be huge to overcome the negative effects of degeneration, and it's unlikely they'll be large enough. A convincing argument by Lenormand & Roze (2024) is that there are many ways recombination could be restored, allowing to circumvent the possible constraints that might be associated with reverting an inversion. First, reversions don't have to be exact to restore recombination. Second, the sex-determining locus can be transposed to another chromosome pair, or an entirely new sex-determining locus might evolve, leading to sex-chromosome turnover which has effectively been observed in several groups. These modelling studies raise important questions that need to be addressed with both theoretical and empirical work. First, is the regulatory hypothesis proposed by Lenormand & Roze (2022) the only plausible mechanism for the maintenance of long-term recombination suppression? The female- and male-specific trans regulators of gene expression that are required for this model, are they readily available or do they need to evolve first? Both theoretical work and empirical studies of nascent sex chromosomes will help to answer these questions. However, nascent sex chromosomes are difficult to detect and dosage compensation is difficult to reveal. Second, how many species today actually have "stable" recombination suppression? Maybe many species are in a transient phase, with different populations having different inversions that are either on their way to being fixed or starting to get counterselected. The models have now shown us some possibilities qualitatively but can they actually be quantified to be able to fit the data and to predict whether an observed case of recombination suppression is transient or stable? The debate will continue, and we need the active contribution of theoretical biologists to help clarify the underlying hypotheses of the proposed mechanisms. Conflict of interest statement: I did co-author a manuscript with D. Roze in 2023, but do not consider this a conflict of interest. The manuscript is the product of discussions that have taken place in a large consortium mainly in 2019. It furthermore deals with an entirely different topic of evolutionary biology. References Jay P, Tezenas E, Véber A, and Giraud T. (2022) Sheltering of deleterious mutations explains the stepwise extension of recombination suppression on sex chromosomes and other supergenes. PLoS Biol.;20:e3001698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001698 | Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes? | Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze | <p style="text-align: justify;">Y and W chromosomes often stop recombining and degenerate. Most work on recombination suppression has focused on the mechanisms favoring recombination arrest in the short term. Yet, the long-term maintenance of reco... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Jos Käfer | 2023-10-27 21:52:06 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer