Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors▲ | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

18 Jan 2023

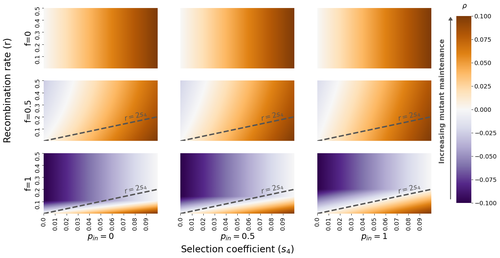

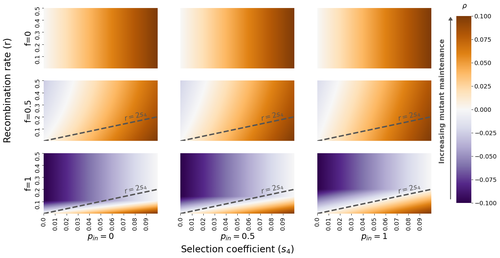

The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfingEmilie Tezenas, Tatiana Giraud, Amandine Veber, Sylvain Billiard https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.07.511119Maintenance of deleterious mutations and recombination suppression near mating-type loci under selfingRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe causes and consequences of the evolution of sexual reproduction are a major topic in evolutionary biology. With advances in sequencing technology, it becomes possible to compare sexual chromosomes across species and infer the neutral and selective processes shaping polymorphism at these chromosomes. Most sex and mating-type chromosomes exhibit an absence of recombination in large genomic regions around the animal, plant or fungal sex-determining genes. This suppression of recombination likely occurred in several time steps generating stepwise increasing genomic regions starting around the sex-determining genes. This mechanism generates so-called evolutionary strata of differentiation between sex chromosomes (Nicolas et al., 2004, Bergero and Charlesworth, 2009, Hartmann et al. 2021). The evolution of extended regions of recombination suppression is also documented on mating-type chromosomes in fungi (Hartmann et al., 2021) and around supergenes (Yan et al., 2020, Jay et al., 2021). The exact reason and evolutionary mechanisms for this phenomenon are still, however, debated. Two hypotheses are proposed: 1) sexual antagonism (Charlesworth et al., 2005), which, nevertheless, does explain the observed occurrence of the evolutionary strata, and 2) the sheltering of deleterious alleles by inversions carrying a lower load than average in the population (Charlesworth and Wall, 1999, Antonovics and Abrams, 2004). In the latter, the mechanism is as follows. A genetic inversion or a suppressor of recombination in cis may exhibit some overdominance behaviour. The inversion exhibiting less recessive deleterious mutations (compared to others at the same locus) may increase in frequency, before at higher frequency occurring at the homozygous state, expressing its genetic load. However, the inversion may never be at the homozygous state if it is genetically linked to a gene in a permanently heterozygous state. The inversion can then be advantageous and may reach fixation at the sex chromosome (Charlesworth and Wall, 1999, Antonovics and Abrams, 2004, Jay et al., 2022). These selective mechanisms promote thus the suppression of recombination around the sex-determining gene, and recessive deleterious mutations are permanently sheltered. This hypothesis is corroborated by the sheltering of deleterious mutations observed around loci under balancing selection (Llaurens et al. 2009, Lenz et al. 2016) and around mating-type genes in fungi and supergenes (Jay et al. 2021, Jay et al., 2022). In this present theoretical study, Tezenas et al. (2022) analyse how linkage to a necessarily heterozygous fungal mating type locus influences the persistence/extinction time of a new mutation at a second selected locus. This mutation can either be deleterious and recessive, or overdominant. There is arbitrary linkage between the two loci, and sexual reproduction occurs either between 1) gametes of different individuals (outcrossing), or 2) by selfing with gametes originating from the same (intra-tetrad) or different (inter-tetrad) tetrads produced by that individual. Note, here, that the mating-type gene does not prevent selfing. The authors study the initial stochastic dynamics of the mutation using a multi-type branching process (and simulations when analytical results cannot be obtained) to compute the extinction time of the deleterious mutation. The main result is that the presence of a mating-type locus always decreases the purging probability and increases the purging time of the mutations under selfing. Ultimately, deleterious mutations can indeed accumulate near the mating-type locus over evolutionary time scales. In a nutshell, high selfing or high intra-tetrad mating do increase the sheltering effect of the mating-type locus. In effect, the outcome of sheltering of deleterious mutations depends on two opposing mechanisms: 1) a higher selfing rate induces a greater production of homozygotes and an increased effect of the purging of deleterious mutations, while 2) a higher intra-tetrad selfing rate (or linkage with the mating-type locus) generates heterozygotes which have a small genetic load (and are favoured). The authors also show that rare events of extremely long maintenance of deleterious mutations can occur. The authors conclude by highlighting the manifold effect of selfing which reduces the effective population size and thus impairs the efficiency of selection and increases the mutational load, while also favouring the purge of deleterious homozygous mutations. Furthermore, this study emphasizes the importance of studying the maintenance and accumulation of deleterious mutations in the vicinity of heterozygous loci (e.g. under balancing selection) in selfing species. References Antonovics J, Abrams JY (2004) Intratetrad Mating and the Evolution of Linkage Relationships. Evolution, 58, 702–709. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00403.x Bergero R, Charlesworth D (2009) The evolution of restricted recombination in sex chromosomes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 24, 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.09.010 Charlesworth D, Morgan MT, Charlesworth B (1990) Inbreeding Depression, Genetic Load, and the Evolution of Outcrossing Rates in a Multilocus System with No Linkage. Evolution, 44, 1469–1489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb03839.x Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B, Marais G (2005) Steps in the evolution of heteromorphic sex chromosomes. Heredity, 95, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800697 Charlesworth B, Wall JD (1999) Inbreeding, heterozygote advantage and the evolution of neo–X and neo–Y sex chromosomes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 266, 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1999.0603 Hartmann FE, Duhamel M, Carpentier F, Hood ME, Foulongne-Oriol M, Silar P, Malagnac F, Grognet P, Giraud T (2021) Recombination suppression and evolutionary strata around mating-type loci in fungi: documenting patterns and understanding evolutionary and mechanistic causes. New Phytologist, 229, 2470–2491. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17039 Jay P, Chouteau M, Whibley A, Bastide H, Parrinello H, Llaurens V, Joron M (2021) Mutation load at a mimicry supergene sheds new light on the evolution of inversion polymorphisms. Nature Genetics, 53, 288–293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-00771-1 Jay P, Tezenas E, Véber A, Giraud T (2022) Sheltering of deleterious mutations explains the stepwise extension of recombination suppression on sex chromosomes and other supergenes. PLOS Biology, 20, e3001698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001698 Lenz TL, Spirin V, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR (2016) Excess of Deleterious Mutations around HLA Genes Reveals Evolutionary Cost of Balancing Selection. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 33, 2555–2564. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw127 Llaurens V, Gonthier L, Billiard S (2009) The Sheltered Genetic Load Linked to the S Locus in Plants: New Insights From Theoretical and Empirical Approaches in Sporophytic Self-Incompatibility. Genetics, 183, 1105–1118. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.109.102707 Nicolas M, Marais G, Hykelova V, Janousek B, Laporte V, Vyskot B, Mouchiroud D, Negrutiu I, Charlesworth D, Monéger F (2004) A Gradual Process of Recombination Restriction in the Evolutionary History of the Sex Chromosomes in Dioecious Plants. PLOS Biology, 3, e4. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0030004 Tezenas E, Giraud T, Véber A, Billiard S (2022) The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfing. bioRxiv, 2022.10.07.511119, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.07.511119 Yan Z, Martin SH, Gotzek D, Arsenault SV, Duchen P, Helleu Q, Riba-Grognuz O, Hunt BG, Salamin N, Shoemaker D, Ross KG, Keller L (2020) Evolution of a supergene that regulates a trans-species social polymorphism. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 240–249. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-1081-1 | The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfing | Emilie Tezenas, Tatiana Giraud, Amandine Veber, Sylvain Billiard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Large regions of suppressed recombination having extended over time occur in many organisms around genes involved in mating compatibility (sex-determining or mating-type genes). The sheltering of deleterious alleles... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Aurelien Tellier | 2022-10-10 13:50:30 | View | |

29 Jul 2020

POSTPRINT

The Y chromosome may contribute to sex-specific ageing in DrosophilaEmily J Brown, Alison H Nguyen, Doris Bachtrog https://doi.org/10.1101/156042Y chromosome makes fruit flies die youngerRecommended by Gabriel Marais, Jean-François Lemaitre and Cristina VieiraIn most animal species, males and females display distinct survival prospect, a phenomenon known as sex gap in longevity (SGL, Marais et al. 2018). The study of SGLs is crucial not only for having a full picture of the causes underlying organisms’ health, aging and death but also to initiate the development of sex-specific anti-aging interventions in humans (Austad and Bartke 2015). Three non-mutually evolutionary causes have been proposed to underlie SGLs (Marais et al. 2018). First, SGLs could be the consequences of sex-differences in life history strategies. For example, evolving dimorphic traits (e.g. body size, ornaments or armaments) may imply unequal physiological costs (e.g. developmental, maintenance) between the sexes and this may result in differences in longevity and aging. Second, mitochondria are usually transmitted by the mother and thus selection is blind to mitochondrial deleterious mutations affecting only males. Such mutations can freely accumulate in the mitochondrial genome and may reduce male longevity, a phenomenon called the mother’s curse (Frank and Hurst 1996). Third, in species with sex chromosomes, all recessive deleterious mutations will be expressed on the single X chromosome in XY males and may reduce their longevity (the unguarded X effect). In addition, the numerous transposable elements (TEs) on the Y chromosome may affect aging. TE activity is normally repressed by epigenetic regulation (DNA methylation, histone modifications and small RNAs). However, it is known that this regulation is disrupted with increasing age. Because of the TE-rich Y chromosome, more TEs may become active in old males than in old females, generating more somatic mutations, accelerating aging and reducing longevity in males (the toxic Y effect, Marais et al. 2018). References Austad, S. N., and Bartke, A. (2015). Sex differences in longevity and in responses to anti-aging interventions: A Mini-Review. Gerontology, 62(1), 40–46. 10.1159/000381472 | The Y chromosome may contribute to sex-specific ageing in Drosophila | Emily J Brown, Alison H Nguyen, Doris Bachtrog | <p>Heterochromatin suppresses repetitive DNA, and a loss of heterochromatin has been observed in aged cells of several species, including humans and *Drosophila*. Males often contain substantially more heterochromatic DNA than females, due to the ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Expression Studies, Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Gabriel Marais | 2020-07-28 15:06:18 | View | |

24 Oct 2019

Testing host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects : a phylogenetic perspectiveEmmanuelle Jousselin, Marianne Elias https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.09510v1Phylogenetic approaches for reconstructing macroevolutionary scenarios of phytophagous insect diversificationRecommended by Hervé Sauquet based on reviews by Brian O'Meara and 1 anonymous reviewerPlant-animal interactions have long been identified as a major driving force in evolution. However, only in the last two decades have rigorous macroevolutionary studies of the topic been made possible, thanks to the increasing availability of densely sampled molecular phylogenies and the substantial development of comparative methods. In this extensive and thoughtful perspective [1], Jousselin and Elias thoroughly review current hypotheses, data, and available macroevolutionary methods to understand how plant-insect interactions may have shaped the diversification of phytophagous insects. First, the authors review three main hypotheses that have been proposed to lead to host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects: the ‘escape and radiate’, ‘oscillation’, and ‘musical chairs’ scenarios, each with their own set of predictions. Jousselin and Elias then synthesize a vast core of recent studies on different clades of insects, where explicit phylogenetic approaches have been used. In doing so, they highlight heterogeneity in both the methods being used and predictions being tested across these studies and warn against the risk of subjective interpretation of the results. Lastly, they advocate for standardization of phylogenetic approaches and propose a series of simple tests for the predictions of host-driven speciation scenarios, including the characterization of host-plant range history and host breadth history, and diversification rate analyses. This helpful review will likely become a new point of reference in the field and undoubtedly help many researchers formalize and frame questions of plant-insect diversification in future studies of phytophagous insects. References [1] Jousselin, E., Elias, M. (2019). Testing Host-Plant Driven Speciation in Phytophagous Insects: A Phylogenetic Perspective. arXiv, 1910.09510, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.09510v1 | Testing host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects : a phylogenetic perspective | Emmanuelle Jousselin, Marianne Elias | During the last two decades, ecological speciation has been a major research theme in evolutionary biology. Ecological speciation occurs when reproductive isolation between populations evolves as a result of niche differentiation. Phytophagous ins... |  | Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Speciation, Species interactions | Hervé Sauquet | 2019-02-25 17:31:33 | View | |

08 Aug 2018

Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutationsE. Noël, E. Fruitet, D. Lelaurin, N. Bonel, A. Ségard, V. Sarda, P. Jarne and P. David https://doi.org//273367Inbreeding compensates for reduced sexual selection in purging deleterious mutationsRecommended by Charles Baer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTwo evolutionary processes have been shown in theory to enhance the effects of natural selection in purging deleterious mutations from a population (here ""natural"" selection is defined as ""selection other than sexual selection""). First, inbreeding, especially self-fertilization, facilitates the removal of deleterious recessive alleles, the effects of which are largely hidden from selection in heterozygotes when mating is random. Second, sexual selection can facilitate the removal of deleterious alleles of arbitrary dominance, with little or no demographic cost, provided that deleterious effects are greater in males than in females (""genic capture""). Inbreeding (especially selfing) and sexual selection are often negatively correlated in nature. Empirical tests of the role of sexual selection in purging deleterious mutations have been inconsistent, potentially due to the positive relationship between sexual selection and intersexual genetic conflict. References [1] Noël, E., Fruitet, E., Lelaurin, D., Bonel, N., Segard, A., Sarda, V., Jarne, P., & David P. (2018). Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutations. bioRxiv, 273367, ver. 3 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/273367 | Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutations | E. Noël, E. Fruitet, D. Lelaurin, N. Bonel, A. Ségard, V. Sarda, P. Jarne and P. David | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (https://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100055). Theory and empirical data showed that two processes can boost selection against deleterious mutations, ... |  | Adaptation, Experimental Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Charles Baer | Anonymous | 2018-03-01 08:12:37 | View |

07 Aug 2023

Pollen-feeding delays reproductive senescence and maintains toxicity of Heliconius eratoErika C. Pinheiro de Castro, Josie McPherson, Glennis Jullian, Anniina L. K. Mattila, Søren Bak, Stephen Montgomery, Chris Jiggins https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.13.523799Impact of pollen-feeding on egg-laying and cyanogenic glucoside abundance in red postman butterfliesRecommended by Adriana Briscoe based on reviews by Carol Boggs, Caroline Mueller and 1 anonymous reviewerGrowth, development and reproduction in animals are all limited by dietary nutrients. Expansion of an organism’s diet to sources not accessible to closely related species reduces food competition, and eases the constraints of nutrient-limited diets. Adult butterflies are herbivorous insects known to feed primarily on nectar from flowers, which is rich in sugars but poor in amino acids. Only certain species in the genus Heliconius are known to also feed on pollen, which is especially rich in amino acids, and is known to prolong their lives by several months. The ability to digest pollen in Heliconius has been linked to specialized feeding behaviors (Krenn et al. 2009) and extra-oral digestion using enzymes, possibly including duplicated copies of cocoonase (Harpel et al. 2016; Smith et al. 2016 and 2018), a protease used by some moths to digest silk upon eclosion from their cocoons. In this reprint, Pinheiro de Castro and colleagues investigated the impact of artificial and natural diets on egg-laying ability, body weight, and cyanogenic glucoside abundance in adult Heliconius erato butterflies of both sexes. Previous studies (Dunlap-Pianka et al. 1981) in H. charithonia demonstrated that access to dietary pollen led to extended egg-laying ability among adult female butterflies compared to females deprived of pollen, and compared to Dryas iulia females which feed only on nectar. In the current study, Pinheiro de Castro et al. (2023) examine the impact of diet on both young and old H. erato, over a longer period of time than the earlier work, highlighting the importance of extending the time period over which effects are evaluated. In addition to extending egg-laying ability in older females, the authors found that pollen in the diet appeared to maintain older female body weight, presumably because the pollen contained nutrients depleted during egg-laying. The authors then investigated the effects of nutrition on the production of cyanogenic glycoside defenses. Heliconius are aposematic butterflies that sequester cyanide-forming defense chemicals from food plants as larvae or synthesize these compounds de novo. The authors found the abundance of cyanogenic glycosides to be significantly greater in butterflies with access to pollen, but again only in older females. Curiously, field studies of male and female H. charithonia butterflies found that females in the wild collected more pollen than males (Mendoza-Cuenca and Macías-Ordóñez 2005). Taken together, these new findings raise the intriguing possibility that females collect more pollen than males, in part, because pollen has a bigger impact on female survival and reproduction. A small limitation of the study is the use of wing length, rather than body weight, at the zero time point. But the trend is clear in both males and females, and it adds supporting detail to the efficacy of pollen feeding as an unusual strategy for increasing fertility and survival in Heliconius butterflies.

References | Pollen-feeding delays reproductive senescence and maintains toxicity of Heliconius erato | Erika C. Pinheiro de Castro, Josie McPherson, Glennis Jullian, Anniina L. K. Mattila, Søren Bak, Stephen Montgomery, Chris Jiggins | <p>Dietary shifts may act to ease energetic constraints and allow organisms to optimise life-history traits. Heliconius butterflies differ from other nectar-feeders due to their unique ability to digest pollen, which provides a reliable source of ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Adriana Briscoe | 2023-02-07 12:59:54 | View | |

20 Sep 2017

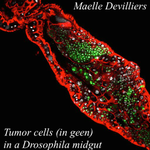

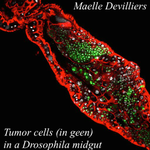

An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in DrosophilaErika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery 10.1101/143560Cancer and loneliness in DrosophilaRecommended by Ana Rivero based on reviews by Ana Rivero and Silvie HuijbenDrosophila flies may not be perceived as a quintessentially social animal, particularly when compared to their eusocial hymenopteran cousins. Although they have no parental care, division of labour or subfertile caste, fruit flies nevertheless exhibit an array of social phenotypes that are potentially comparable to those of their highly social relatives. In the wild, Drosophila adults cluster around food resources where courtship, mating activity and oviposition occur. Recent work has shown not only that social interactions in these clusters condition many aspects of the behaviour and physiology of the flies [1] but also, and perhaps more unexpectedly, that social isolation has a negative impact on their fitness [2]. Many studies in humans point to the role of social isolation as a source of stress that can induce and accelerate disease progression. The ultimate proof of the connection between social interaction and disease is however mired in confounding variables and alternative explanations so the subject, though crucial, remains controversial. With a series of elegant experiments using Drosophila flies that develop an inducible form of intestinal cancer, Dawson et al [3] show that cancer progresses more rapidly in flies maintained in isolation than in flies maintained with other cancerous flies. Further, cancerous flies kept with non-cancerous flies, fare just as badly as when kept alone. Their experiments suggest that this is due to the combined effect of healthy flies avoiding contact with cancerous flies (even though this is a non-contagious disease), and of cancerous flies having higher quality interactions with other cancerous flies than with healthy ones. Perceived isolation is therefore as pernicious as real isolation when it comes to cancer progression in these flies. Like all good research, this study opens up as many questions as it answers, in particular the why and wherefores of the flies’ extraordinary social behaviour in the face of disease. References [1] Camiletti AL and Thompson GJ. 2016. Drosophila as a genetically tractable model for social insect behavior. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 4: 40. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2016.00040 [2] Ruan H and Wu C-F. 2008. Social interaction-mediated lifespan extension of Drosophila Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 105: 7506-7510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711127105 [3] Dawson E, Bailly T, Dos Santos J, Moreno C, Devilliers M, Maroni B, Sueur C, Casali A, Ujvari B, Thomas F, Montagne J, Mery F. 2017. An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila. BiorXiv, 143560, ver. 3 of 19th September 2017. doi: 10.1101/143560 | An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila | Erika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery | The ecological benefits of sociality in gregarious species are widely acknowledged. However, only limited data is available on how the social environment influences non-communicable disease outcomes. For instance, despite extensive research over t... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Ana Rivero | 2017-05-30 08:55:16 | View | |

26 Sep 2017

Lacking conservation genomics in the giant Galápagos tortoiseEtienne Loire, Nicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/101980A genomic perspective is needed for the re-evaluation of species boundaries, evolutionary trajectories and conservation strategies for the Galápagos giant tortoisesRecommended by Michael C. Fontaine based on reviews by 4 anonymous reviewersGenome-wide data obtained from even a small number of individuals can provide unprecedented levels of detail about the evolutionary history of populations and species [1], determinants of genetic diversity [2], species boundaries and the process of speciation itself [3]. Loire and Galtier [4] present a clear example, using the emblematic Galápagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis nigra), of how multi-species comparative population genomic approaches can provide valuable insights about population structure and species delimitation even when sample sizes are limited but the number of loci is large and distributed across the genome. Galápagos giant tortoises are endemic to the Galápagos Islands and are currently recognized as an endangered, multi-species complex including both extant and extinct taxa. Taxonomic definitions are based on morphology, geographic isolation and population genetic evidence based on short DNA sequences of the mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) and/or a dozen or so nuclear microsatellite loci [5-8]. The species complex enjoys maximal protection. Population recoveries have been quite successful and spectacular conservation programs based on mitochondrial genes and microsatellites are ongoing. This includes for example individual translocations, breeding program, “hybrid” sterilization or removal, and resurrection of extinct lineages). In 2013, Loire et al. [9] provided the first population genomic analyses based on genome scale data (~1000 coding loci derived from blood-transcriptomes) from five individuals, encompassing three putative “species”: Chelonnoidis becki, C. porteri and C. vandenburghi. Their results raised doubts about the validity/accuracy of the currently accepted designations of “genetic distinctiveness”. However, the implications for conservation and management have remained unnoticed. In 2017, Loire and Galtier [4] have re-appraised this issue using an original multi-species comparative population genomic analysis of their previous data set [9]. Based on a comparison of 53 animal species, they show that both the level of genome-wide neutral diversity (πS) and level of population structure estimated using the inbreeding coefficient (F) are much lower than would be expected from a sample covering multiple species. The observed values are more comparable to those typically reported at the “among population” level within a single species such as human (Homo sapiens). The authors go to great length to assess the sensitivity of their method to detect population structure (or lack thereof) and show that their results are robust to potential issues, such as contamination and sequencing errors that can occur with Next Generation Sequencing techniques; and biases related to the small sample size and sub-sampling of individuals. They conclude that published mtDNA and microsatellite-based assessment of population structure and species designations may be biased towards over-splitting. This manuscript is a very good read as it shows the potential of the now relatively affordable genome-wide data for helping to both resolve and clarify population and species boundaries, illuminate demographic trends, evolutionary trajectories of isolated groups, patterns of connectivity among them, and test for evidence of local adaptation and even reproductive isolation. The comprehensive information provided by genome-wide data can critically inform and assist the development of the best strategies to preserve endangered populations and species. Loire and Galtier [4] make a strong case for applying genomic data to the Galápagos giant tortoises, which is likely to redirect conservation efforts more effectively and at lower cost. The case of the Galápagos giant tortoises is certainly a very emblematic example, which will find an echo in many other endangered species conservation programs. References [1] Li H and Durbin R. 2011. Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature, 475: 493–496. doi: 10.1038/nature10231 [2] Romiguier J, Gayral P, Ballenghien M, Bernard A, Cahais V, Chenuil A, Chiari Y, Dernat R, Duret L, Faivre N, Loire E, Lourenco JM, Nabholz B, Roux C, Tsagkogeorga G, Weber AA-T, Weinert LA, Belkhir K, Bierne N, Glémin S and Galtier N. 2014. Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature, 515: 261–263. doi: 10.1038/nature13685 [3] Roux C, Fraïsse C, Romiguier J, Anciaux Y, Galtier N and Bierne N. 2016. Shedding light on the grey zone of speciation along a continuum of genomic divergence. PLoS Biology, 14: e2000234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2000234 [4] Loire E and Galtier N. 2017. Lacking conservation genomics in the giant Galápagos tortoise. bioRxiv 101980, ver. 4 of September 26, 2017. doi: 10.1101/101980 [5] Beheregaray LB, Ciofi C, Caccone A, Gibbs JP and Powell JR. 2003. Genetic divergence, phylogeography and conservation units of giant tortoises from Santa Cruz and Pinzón, Galápagos Islands. Conservation Genetics, 4: 31–46. doi: 10.1023/A:1021864214375 [6] Ciofi C, Milinkovitch MC, Gibbs JP, Caccone A and Powell JR. 2002. Microsatellite analysis of genetic divergence among populations of giant Galápagos tortoises. Molecular Ecology, 11: 2265–2283. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01617.x [7] Garrick RC, Kajdacsi B, Russello MA, Benavides E, Hyseni C, Gibbs JP, Tapia W and Caccone A. 2015. Naturally rare versus newly rare: demographic inferences on two timescales inform conservation of Galápagos giant tortoises. Ecology and Evolution, 5: 676–694. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1388 [8] Poulakakis N, Edwards DL, Chiari Y, Garrick RC, Russello MA, Benavides E, Watkins-Colwell GJ, Glaberman S, Tapia W, Gibbs JP, Cayot LJ and Caccone A. 2015. Description of a new Galápagos giant tortoise species (Chelonoidis; Testudines: Testudinidae) from Cerro Fatal on Santa Cruz island. PLoS ONE, 10: e0138779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138779 [9] Loire E, Chiari Y, Bernard A, Cahais V, Romiguier J, Nabholz B, Lourenço JM and Galtier N. 2013. Population genomics of the endangered giant Galápagos tortoise. Genome Biology, 14: R136. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-12-r136 | Lacking conservation genomics in the giant Galápagos tortoise | Etienne Loire, Nicolas Galtier | <p>Conservation policy in the giant Galápagos tortoise, an iconic endangered animal, has been assisted by genetic markers for ~15 years: a dozen loci have been used to delineate thirteen (sub)species, between which hybridization is prevented. Here... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation, Systematics / Taxonomy | Michael C. Fontaine | 2017-01-21 15:34:00 | View | |

09 Dec 2019

Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasitesEva JP Lievens, Yannis Michalakis, Thomas Lenormand https://doi.org/10.1101/621581Trade-offs in fitness components and ecological source-sink dynamics affect host specialisation in two parasites of Artemia shrimpsRecommended by Frédéric Guillaume based on reviews by Anne Duplouy, Seth Barribeau and Cindy Gidoin based on reviews by Anne Duplouy, Seth Barribeau and Cindy Gidoin

Ecological specialisation, especially among parasites infecting a set of host species, is ubiquitous in nature. Host specialisation can be understood as resulting from trade-offs in parasite infectivity, virulence and growth. However, it is not well understood how variation in these trade-offs shapes the overall fitness trade-off a parasite faces when adapting to multiple hosts. For instance, it is not clear whether a strong trade-off in one fitness component may sufficiently constrain the evolution of a generalist parasite despite weak trade-offs in other components. A second mechanism explaining variation in specialisation among species is habitat availability and quality. Rare habitats or habitats that act as ecological sinks will not allow a species to persist and adapt, preventing a generalist phenotype to evolve. Understanding the prevalence of those mechanisms in natural systems is crucial to understand the emergence and maintenance of host specialisation, and biodiversity in general. References [1] Lievens, E.J.P., Michalakis, Y. and Lenormand, T. (2019). Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasites. bioRxiv, 621581, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/621581 | Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasites | Eva JP Lievens, Yannis Michalakis, Thomas Lenormand | <p>The evolution of host specialization has been studied intensively, yet it is still often difficult to determine why parasites do not evolve broader niches – in particular when the available hosts are closely related and ecologically similar. He... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Experimental Evolution, Life History, Species interactions | Frédéric Guillaume | 2019-05-13 13:44:34 | View | |

23 Jan 2023

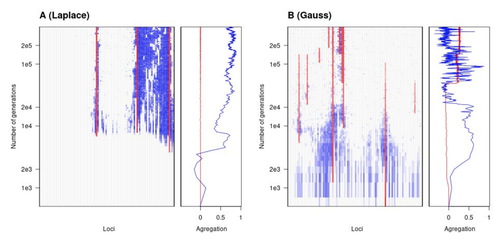

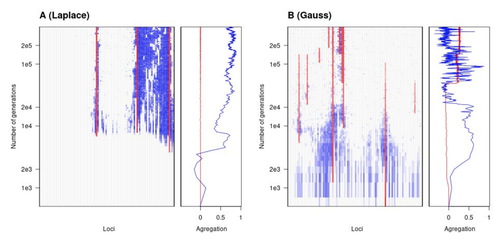

The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a clineFabien Laroche, Thomas Lenormand https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.30.498280Environmental and fitness landscapes matter for the genetic basis of local adaptationRecommended by Charles Mullon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Natural landscapes are often composite, with spatial variation in environmental factors being the norm rather than exception. Adaptation to such variation is a major driver of diversity at all levels of biological organization, from genes to phenotypes, species and ultimately ecosystems. While natural selection favours traits that show a better fit to local conditions, the genomic response to such selection is not necessarily straightforward. This is because many quantitative traits are complex and the product of many loci, each with a small to moderate phenotypic contribution. Adapting to environmental challenges that occur in narrow ranges may thus prove difficult as each individual locus is easily swamped by alleles favoured across the rest of the population range. To better understand whether and how evolution overcomes such a hurdle, Laroche and Lenormand [1] combine quantitative genetics and population genetic modelling to track genomic changes that underpin a trait whose fitness optimum differs between a certain spatial range, referred to as a “pocket”, and the rest of the habitat. As it turns out from their analysis, one critical and probably underappreciated factor in determining the type of genetic architecture that evolves is how fitness declines away from phenotypic optima. One classical and popular model of fitness landscape that relates trait value to reproductive success is Gaussian, whereby small trait variations away from the optimum result in even smaller variations in fitness. This facilitates local adaptation via the invasion of alleles of small effects as carriers inside the pocket show a better fit while those outside the pocket only suffer a weak fitness cost. By contrast, when the fitness landscape is more peaked around the optimum, for instance where the decline is linear, adaptation through weak effect alleles is less likely, requiring larger pockets that are less easily swamped by alleles selected in the rest of the range. In addition to mathematically investigating the initial emergence of local adaptation, Laroche and Lenormand use computer simulations to look at its long-term maintenance. In principle, selection should favour a genetic architecture that consolidates the phenotype and increases its heritability, for instance by grouping several alleles of large effects close to one another on a chromosome to avoid being broken down by meiotic recombination. Whether or not this occurs also depends on the fitness landscape. When the landscape is Gaussian, the genetic architecture of the trait eventually consists of tightly linked alleles of large effects. The replacement of small effects by large effects loci is here again promoted by the slow fitness decline around the optimum. This is because any shift in architecture in an adapted population requires initially crossing a fitness valley. With a Gaussian landscape, this valley is shallow enough to be crossed, facilitated by a bit of genetic drift. By contrast, when fitness declines linearly around the optimum, genetic architecture is much less evolutionarily labile as any architecture change initially entails a fitness cost that is too high to bear. Overall, Laroche and Lenormand provide a careful and thought-provoking analysis of a classical problem in population genetics. In addition to questioning some longstanding modelling assumptions, their results may help understand why differentiated populations are sometimes characterized by “genomic islands” of divergence, and sometimes not. References [1] Laroche F, Lenormand T (2022) The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a cline. bioRxiv, 2022.06.30.498280, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.30.498280 | The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a cline | Fabien Laroche, Thomas Lenormand | <p>Local adaptation is pervasive. It occurs whenever selection favors different phenotypes in different environments, provided that there is genetic variation for the corresponding traits and that the effect of selection is greater than the effect... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics | Charles Mullon | 2022-07-07 08:46:47 | View | |

14 Apr 2021

Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host speciesFanny Cavigliasso, Hugo Mathé-Hubert, Jean-Luc Gatti, Dominique Colinet, Marylène Poirié https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.24.353417What makes a parasite successful? Parasitoid wasp venoms evolve rapidly in a host-specific mannerRecommended by Élio Sucena based on reviews by Simon Fellous, alexandre leitão and 1 anonymous reviewerParasitoid wasps have developed different mechanisms to increase their parasitic success, usually at the expense of host survival (Fellowes and Godfray, 2000). Eggs of these insects are deposited inside the juvenile stages of their hosts, which in turn deploy several immune response strategies to eliminate or disable them (Yang et al., 2020). Drosophila melanogaster protects itself against parasitoid attacks through the production of specific elongated haemocytes called lamellocytes which form a capsule around the invading parasite (Lavine and Strand, 2002; Rizki and Rizki, 1992) and the subsequent activation of the phenol-oxidase cascade leading to the release of toxic radicals (Nappi et al., 1995). On the parasitoid side, robust responses have evolved to evade host immune defenses as for example the Drosophila-specific endoparasite Leptopilina boulardi, which releases venom during oviposition that modifies host behaviour (Varaldi et al., 2006) and inhibits encapsulation (Gueguen et al., 2011; Martinez et al., 2012).

References Cavigliasso, F., Mathé-Hubert, H., Gatti, J.-L., Colinet, D. and Poirié, M. (2021) Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host species. bioRxiv, 2020.10.24.353417, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.24.353417 Cavigliasso, F., Mathé-Hubert, H., Kremmer, L., Rebuf, C., Gatti, J.-L., Malausa, T., Colinet, D., Poiré, M. and Léne. (2019). Rapid and Differential Evolution of the Venom Composition of a Parasitoid Wasp Depending on the Host Strain. Toxins, 11(629). https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11110629 Colinet, D., Deleury, E., Anselme, C., Cazes, D., Poulain, J., Azema-Dossat, C., Belghazi, M., Gatti, J. L. and Poirié, M. (2013). Extensive inter- and intraspecific venom variation in closely related parasites targeting the same host: The case of Leptopilina parasitoids of Drosophila. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 43(7), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.03.010 Colinet, D., Dubuffet, A., Cazes, D., Moreau, S., Drezen, J. M. and Poirié, M. (2009). A serpin from the parasitoid wasp Leptopilina boulardi targets the Drosophila phenoloxidase cascade. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 33(5), 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dci.2008.11.013 Fellowes, M. D. E. and Godfray, H. C. J. (2000). The evolutionary ecology of resistance to parasitoids by Drosophila. Heredity, 84(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00685.x Gueguen, G., Rajwani, R., Paddibhatla, I., Morales, J. and Govind, S. (2011). VLPs of Leptopilina boulardi share biogenesis and overall stellate morphology with VLPs of the heterotoma clade. Virus Research, 160(1–2), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2011.06.005 Lavine, M. D. and Strand, M. R. (2002). Insect hemocytes and their role in immunity. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 32(10), 1295–1309. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00092-9 Martinez, J., Duplouy, A., Woolfit, M., Vavre, F., O’Neill, S. L. and Varaldi, J. (2012). Influence of the virus LbFV and of Wolbachia in a host-parasitoid interaction. PloS One, 7(4), e35081. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035081 Nappi, A. J., Vass, E., Frey, F. and Carton, Y. (1995). Superoxide anion generation in Drosophila during melanotic encapsulation of parasites. European Journal of Cell Biology, 68(4), 450–456. Poirié, M., Colinet, D. and Gatti, J. L. (2014). Insights into function and evolution of parasitoid wasp venoms. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 6, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2014.10.004 Rizki, T. M. and Rizki, R. M. (1992). Lamellocyte differentiation in Drosophila larvae parasitized by Leptopilina. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 16(2–3), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-305X(92)90011-Z Schlenke, T. A., Morales, J., Govind, S. and Clark, A. G. (2007). Contrasting infection strategies in generalist and specialist wasp parasitoids of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Pathogens, 3(10), 1486–1501. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.0030158 Varaldi, J., Petit, S., Boulétreau, M. and Fleury, F. (2006). The virus infecting the parasitoid Leptopilina boulardi exerts a specific action on superparasitism behaviour. Parasitology, 132(Pt 6), 747–756. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182006009930 Yang, L., Qiu, L., Fang, Q., Stanley, D. W. and Gong‐Yin, Y. (2020). Cellular and humoral immune interactions between Drosophila and its parasitoids. Insect Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7917.12863

| Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host species | Fanny Cavigliasso, Hugo Mathé-Hubert, Jean-Luc Gatti, Dominique Colinet, Marylène Poirié | <p>Female endoparasitoid wasps usually inject venom into hosts to suppress their immune response and ensure offspring development. However, the parasitoid’s ability to evolve towards increased success on a given host simultaneously with the evolut... |  | Experimental Evolution, Species interactions | Élio Sucena | 2020-10-26 15:00:55 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer