Sexual selection goes dynamic

Recommended by Michael D Greenfield based on reviews by Frédéric Guillaume and 1 anonymous reviewer

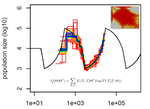

150 years after Darwin published ‘Descent of man and selection in relation to sex’ (Darwin, 1871), the evolutionary mechanism that he laid out in his treatise continues to fascinate us. Sexual selection is responsible for some of the most spectacular traits among animals, and plants, and it appeals to our interest in all things reproductive and sexual (Bell, 1982). In addition, sexual selection poses some of the more intractable problems in evolutionary biology: Its realm encompasses traits that are subject to markedly different selection pressures, particularly when distinct, yet associated, traits tend to be associated with males, e.g. courtship signals, and with females, e.g. preferences (cf. Ah-King & Ahnesjo, 2013). While separate, such traits cannot evolve independently of each other (Arnqvist & Rowe, 2005), and complex feedback loops and correlations between them are predicted (Greenfield et al., 2014). Traditionally, sexual selection has been modelled under simplifying assumptions, and quantitative genetic approaches that avoided evolutionary dynamics have prevailed. New computing methods may be able to free the field from these constraints, and a trio of theoreticians (Chevalier, De Coligny & Labonne 2020) describe here a novel application of a ‘demo-genetic agent (or individual) based model’, a mouthful hereafter termed DG-ABM, for arriving at a holistic picture of the sexual selection trajectory. The application is built on the premise that traits, e.g. courtship, preference, gamete investment, competitiveness for mates, can influence the genetic architecture, e.g. correlations, of those traits. In turn, the genetic architecture can influence the expression and evolvability of the traits. Much of this influence occurs via demographic features, i.e. social environment, generated by behavioral interactions during sexual advertisement, courtship, mate guarding, parental care, post-mating dispersal, etc.

The authors provide a lengthy verbal description of their model, specifying the genomic and behavioral parameters that can be set and how a ‘run’ may be initialized. There is a link to an internet site where users can then enter their own parameter values and begin exploring hypotheses. Back in the article several simulations illustrate simple tests; e.g. how gamete investment and preference jointly evolve given certain survival costs. One obvious test would have been the preference – courtship genetic correlation that represents the core of Fisherian runaway selection, and it is regrettable that it was not examined under a range of demographic parameters. As presented the author’s DG-ABM appears particularly geared toward mating systems in ‘higher’ vertebrates, where couples form during a discrete mating season and are responsible for most reproduction. It is not clear how applicable the model could be to a full range of mating systems and nuances, including those in arthropods and other invertebrates as well as plants.

What is the likely value of the DG-ABM for sexual selection researchers? We will not be able to evaluate its potential impact until readers with specialized understanding of a question and taxon begin exploring and comparing their results with prior expectations. Of course, lack of congruence with earlier predictions would not invalidate the model. Hopefully, some of these specialists will have opportunities for comparing results with pertinent empirical data.

References

Ah-King, M. and Ahnesjo, I. 2013. The ‘sex role’ concept: An overview and evaluation Evolutionary Biology, 40, 461-470. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11692-013-9226-7

Arnqvist, G. and Rowe, L. 2005. Sexual Conflict. Princeton University Press, Princeton. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400850600

Bell, G. 1982. The Masterpiece of Nature: The Evolution and Genetics of Sexuality. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Chevalier, L., De Coligny, F. and Labonne, J. (2020) A demogenetic individual based model for the evolution of traits and genome architecture under sexual selection. bioRxiv, 2020.04.01.014514, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.01.014514

Darwin, C. 1871. The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. J. Murray, London.

Greenfield, M.D., Alem, S., Limousin, D. and Bailey, N.W. 2014. The dilemma of Fisherian sexual selection: Mate choice for indirect benefits despite rarity and overall weakness of trait-preference genetic correlation. Evolution, 68, 3524-3536. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12542

| A demogenetic agent based model for the evolution of traits and genome architecture under sexual selection | Louise Chevalier, François de Coligny, Jacques Labonne | <p>Sexual selection has long been known to favor the evolution of mating behaviors such as mate preference and competitiveness, and to affect their genetic architecture, for instance by favoring genetic correlation between some traits. Reciprocall... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics, Sexual Selection | Michael D Greenfield | | 2020-04-02 14:44:25 | View |

Multi-gene and lineage comparative assessment of the strength of selection in Hymenoptera

Recommended by Bertanne Visser based on reviews by Michael Lattorff and 1 anonymous reviewer

Genetic variation is the raw material for selection to act upon and the amount of genetic variation present within a population is a pivotal determinant of a population’s evolutionary potential. A large effective population size, i.e., the ideal number of individuals experiencing the same amount of genetic drift and inbreeding as an actual population, Ne (Wright 1931, Crow 1954), thus increases the probability of long-term survival of a population. However, natural populations, as opposed to theoretical ones, rarely adhere to the requirements of an ideal panmictic population (Sjödin et al. 2005). A range of circumstances can reduce Ne, including the structuring of populations (through space and time, as well as age and developmental stages) and inbreeding (Charlesworth 2009). In mammals, species with a larger body mass (as a proxy for lower Ne) were found to have a higher rate of nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions (that alter the amino acid sequence of a protein), as well as radical amino acid substitutions (altering the physicochemical properties of a protein) (Popadin et al. 2007). In general, low effective population sizes increase the chance of mutation accumulation and drift, while reducing the strength of selection (Sjödin et al. 2005).

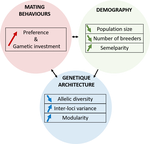

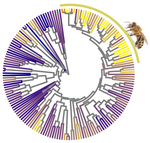

In this paper, Weyna and Romiguier (2021) set out to test if parasitism, body size, geographic range, and/or eusociality affect the strength of selection in Hymenoptera. Hymenoptera include the bees, wasps and ants and is an extraordinarily diverse order within the insects. It was recently estimated that Hymenoptera is the most speciose order of the animal kingdom (Forbes et al. 2018). Hymenoptera are further characterized by an impressive radiation of parasitic species, mainly parasitoids, that feed in or on a single host individual to complete their own development (Godfray 1994). All hymenopterans share the same sex determination system: haplo-diploidy, where unfertilized eggs are haploid males and fertilized eggs are diploid females. Compared to other animals, Hymenoptera further contain an impressive number of clades that evolved eusociality (Rehan and Toth 2015), in which societies show a clear division of labor for reproduction (i.e., castes) and cooperative brood care. Hymenopterans thus represent a diverse and interesting group of insects to investigate potential factors affecting strength of selection and Ne.

Using a previously published phylogenomic dataset containing 3256 genes and 169 hymenopteran species (Peters et al. 2017), Weyna and Romiguier (2021) estimated mean genomic dN/dS ratios (nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rates) for each species and compared these values between parasitic and non-parasitic species, eusocial and solitary species, and in relation to body size, parasitoid-specific traits and geographic range, thought to affect the effective population size and strength of selection. The use of a large number of species, as well as several distinct traits is a clear asset of this study. The authors found no effect of body size, geographic range or parasitism (including a range of parasitoid-specific traits). There was an effect, however, of eusociality where dN/dS increased in three out of four eusocial lineages. Future studies including more independent evolutionary transitions to eusociality can lend further support that eusocial species indeed reduces the efficiency of selection. The most intriguing result was that for solitary and social bees, with high dN/dS ratios and a strong signature of relaxed selection (i.e., the elimination or reduction of a source of selection (Lahti et al. 2009). The authors suggest that the pollen-collecting behaviors of these species can constrain Ne, as pollen availability varies at both a spatial and temporal scale, requiring a large investment in foraging that may in turn limit reproductive output. It would be interesting to see if other pollen feeders, such as certain beetles, flies, butterflies and moths, as well as mites and spiders, experience relaxed selection as a consequence of the trade-off between energy investment in pollen foraging versus fecundity.

References

Charlesworth, B. (2009). Effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation. Nature Reviews Genetics, 10(3), 195-205. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2526

Crow, J. F. (1954) Statistics and Mathematics in Biology (eds Kempthorne, O., Bancroft, T. A., Gowen, J. W. & Lush, J. L.) 543–556 (Iowa State Univ. Press, Ames, Iowa)

Forbes, A. A., Bagley, R. K., Beer, M. A., Hippee, A. C., and Widmayer, H. A. (2018). Quantifying the unquantifiable: why Hymenoptera, not Coleoptera, is the most speciose animal order. BMC ecology, 18(1), 1-11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-018-0176-x

Godfray, H. C. J. (1994) Parasitoids: Behavioral and Evolutionary Ecology. Vol. 67, Princeton University Press, 1994. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvs32rmp

Lahti et al. (2009). Relaxed selection in the wild. Trends in ecology & evolution, 24(9), 487-496. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.010

Peters et al. (2017). Evolutionary history of the Hymenoptera. Current Biology, 27(7), 1013-1018. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.027

Popadin, K., Polishchuk, L. V., Mamirova, L., Knorre, D., and Gunbin, K. (2007). Accumulation of slightly deleterious mutations in mitochondrial protein-coding genes of large versus small mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(33), 13390-13395. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0701256104

Rehan, S. M., and Toth, A. L. (2015). Climbing the social ladder: the molecular evolution of sociality. Trends in ecology & evolution, 30(7), 426-433. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2015.05.004

Sjödin, P., Kaj, I., Krone, S., Lascoux, M., and Nordborg, M. (2005). On the meaning and existence of an effective population size. Genetics, 169(2), 1061-1070. doi: https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.104.026799

Weyna, A., and Romiguier, J. (2021) Relaxation of purifying selection suggests low effective population size in eusocial Hymenoptera and solitary pollinating bees. bioRxiv, 2020.04.14.038893, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.14.038893

Wright, S. (1931). Evolution in Mendelian populations. Genetics, 16(2), 97-159.

| Relaxation of purifying selection suggests low effective population size in eusocial Hymenoptera and solitary pollinating bees | Arthur Weyna, Jonathan Romiguier | <p>With one of the highest number of parasitic, eusocial and pollinator species among all insect orders, Hymenoptera features a great diversity of lifestyles. At the population genetic level, such life-history strategies are expected to decrease e... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Genome Evolution, Life History, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Bertanne Visser | | 2020-04-21 17:30:57 | View |

Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis

David Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265

Temperature effects on virulence evolution of wMelPop Wolbachia in Drosophila melanogaster

Recommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Shira Houwenhuyse and 3 anonymous reviewers

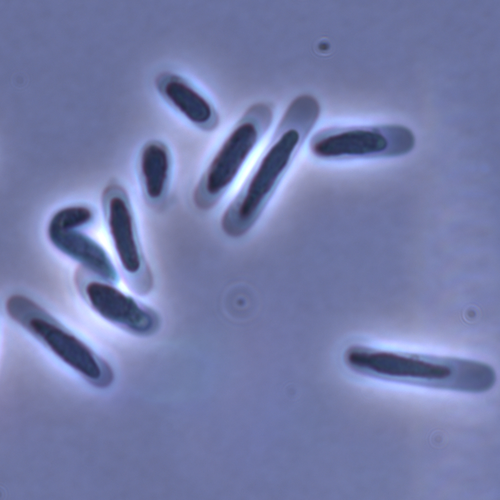

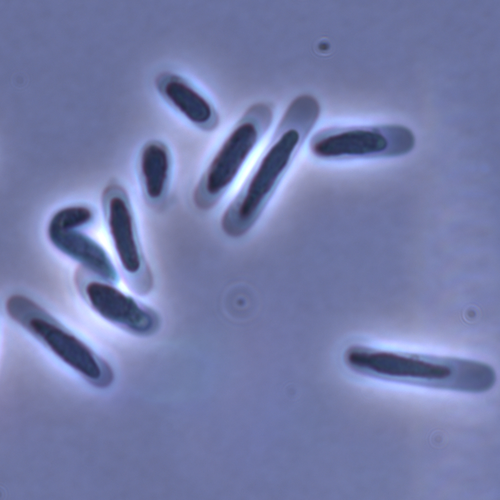

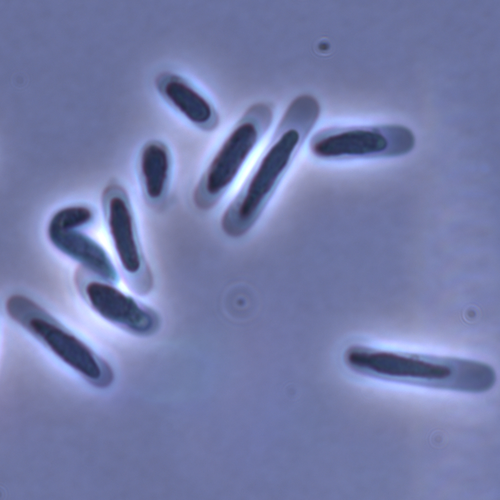

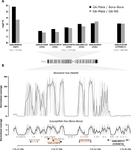

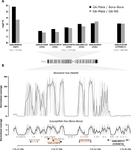

Monnin et al. [1] here studied how Drosophila populations are affected when exposed to a high virulent endosymbiotic wMelPop Wolbachia strain and why virulent vertically transmitting endosymbionts persist in nature. This virulent wMelPop strain has been described to be a blocker of dengue and other arboviral infections in arthropod vector species, such as Aedes aegypti. Whereas it can thus function as a mutualistic symbiont, it here acts as an antagonist along the mutualism-antagonism continuum symbionts operate. The wMelPop strain is not a natural occurring strain in Drosophila melanogaster and thus the start of this experiment can be seen as a novel host-pathogen association. Through experimental evolution of 17 generations, the authors studied how high temperature affects wMelPop Wolbachia virulence and Drosophila melanogaster survival. The authors used Drosophila strains that were selected for late reproduction, given that this should favor evolution to a lower virulence. Assumptions for this hypothesis are not given in the manuscript here, but it can indeed be assumed that energy that is assimilated to symbiont tolerance instead of reproduction may lead to reduced virulence evolution. This has equally been suggested by Reyserhove et al. [2] in a dynamics energy budget model tailored to Daphnia magna virulence evolution upon a viral infection causing White fat Cell disease, reconstructing changing environments through time.

Contrary to their expectations for vertically transmitting symbionts, the authors did not find a reduction in wMelPop Wolbachia virulence during the course of the experimental evolution experiment under high temperature. Important is what this learns for virulence evolution, also for currently horizontal transmitting disease epidemics (such as COVID-19). It mainly reflects that evolution of virulence for new host-pathogen associations is difficult to predict and that it may take multiple generations before optimal levels of virulence are reached [3,4]. These optimal levels of virulence will depend on trade-offs with other life history traits of the symbiont, but also on host demography, host heterogeneity, amongst others [5,6]. Multiple microbial interactions may affect the outcome of virulence evolution [7]. Given that no germ-free individuals were used, it can be expected that other components of the Drosophila microbiome may have played a role in the virulence evolution. In most cases, microbiota have been described as defensive or protective for virulent symbionts [8], but they may also have stimulated the high levels of virulence. Especially, given that upon higher temperatures, Wolbachia growth may have been increased, host metabolic demands increased [9], host immune responses affected and microbial communities changed [10]. This may have resulted in increased competitive interactions to retrieve host resources, sustaining high virulence levels of the symbiont.

A nice asset of this study is that the phenotypic results obtained in the experimental evolution set-up were linked with wMelPop density measurement and octomom copy number quantifications. Octomom is a specific 8-n genes region of the Wolbachia genome responsible for wMelPop virulence, so there is a link between the phenotypic and molecular functions of the involved symbiont. The authors found that density, octomom copy number and virulence were correlated to each other. An important note the authors address in their discussion is that, to exclude the possibility that octomom copy number has an effect on density, and density on virulence, the effect of these variables should be assessed independently of temperature and age. The obtained results are a valuable contribution to the ongoing debate on the relationship between wMelPop octomom copy number, density and virulence.

References

[1] Monnin, D., Kremer, N., Michaud, C., Villa, M., Henri, H., Desouhant, E. and Vavre, F. (2020) Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis. bioRxiv, 2020.04.26.062265, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265

[2] Reyserhove, L., Samaey, G., Muylaert, K., Coppé, V., Van Colen, W., and Decaestecker, E. (2017). A historical perspective of nutrient change impact on an infectious disease in Daphnia. Ecology, 98(11), 2784-2798. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.1994

[3] Ebert, D., and Bull, J. J. (2003). Challenging the trade-off model for the evolution of virulence: is virulence management feasible?. Trends in microbiology, 11(1), 15-20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-842X(02)00003-3

[4] Houwenhuyse, S., Macke, E., Reyserhove, L., Bulteel, L., and Decaestecker, E. (2018). Back to the future in a petri dish: Origin and impact of resurrected microbes in natural populations. Evolutionary Applications, 11(1), 29-41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12538

[5] Day, T., and Gandon, S. (2007). Applying population‐genetic models in theoretical evolutionary epidemiology. Ecology Letters, 10(10), 876-888. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01091.x

[6] Alizon, S., Hurford, A., Mideo, N., and Van Baalen, M. (2009). Virulence evolution and the trade‐off hypothesis: history, current state of affairs and the future. Journal of evolutionary biology, 22(2), 245-259. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01658.x

[7] Alizon, S., de Roode, J. C., and Michalakis, Y. (2013). Multiple infections and the evolution of virulence. Ecology letters, 16(4), 556-567. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12076

[8] Decaestecker, E., and King, K. (2019). Red queen dynamics. Reference module in earth systems and environmental sciences, 3, 185-192. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.10550-0

[9] Kirk, D., Jones, N., Peacock, S., Phillips, J., Molnár, P. K., Krkošek, M., and Luijckx, P. (2018). Empirical evidence that metabolic theory describes the temperature dependency of within-host parasite dynamics. PLoS biology, 16(2), e2004608. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2004608

[10] Frankel-Bricker, J., Song, M. J., Benner, M. J., and Schaack, S. (2019). Variation in the microbiota associated with Daphnia magna across genotypes, populations, and temperature. Microbial ecology, 1-12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-019-01412-9

| Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis | David Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre | <p>Evolutionary theory predicts that vertically transmitted symbionts are selected for low virulence, as their fitness is directly correlated to that of their host. In contrast with this prediction, the Wolbachia strain wMelPop drastically reduces... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Species interactions | Ellen Decaestecker | | 2020-04-29 19:16:56 | View |

Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

Djampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.30.069948

DNA transposons drive genome evolution of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

Recommended by Ines Alvarez based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers

Duplications, mutations and recombination may be considered the main sources of genomic variation and evolution. In addition, sexual recombination is essential in purging deleterious mutations and allowing advantageous allelic combinations to occur (Glémin et al. 2019). However, in parthenogenetic asexual organisms, variation cannot be explained by sexual recombination, and other mechanisms must account for it. Although it is known that transposable elements (TE) may influence on genome structure and gene expression patterns, their role as a primary source of genomic variation and rapid adaptability has received less attention. An important role of TE on adaptive genome evolution has been documented for fungal phytopathogens (Faino et al. 2016), suggesting that TE activity might explain the evolutionary dynamics of this type of organisms.

The phytopathogen nematode Meloidogyne incognita is one of the worst agricultural pests in warm climates (Savary et al. 2019). This species, as well as other root-knot nematodes (RKN), shows a wide geographical distribution range infecting diverse groups of plants. Although allopolyploidy may have played an important role on the wide adaptation of this phytopathogen, it may not explain by itself the rapid changes required to overcome plant resistance in a few generations. Paradoxically, M. incognita reproduces asexually via mitotic parthenogenesis (Trudgill and Blok 2001; Castagnone-Sereno and Danchin 2014) and only few single nucleotide variations were identified between different host races isolates (Koutsovoulos et al. 2020). Therefore, this is an interesting model to explore other sources of genomic variation such the TE activity and its role on the success and adaptability of this phytopathogen.

To address these questions, Kozlowski et al. (2020) estimated the TE mobility across 12 geographical isolates that presented phenotypic variations in Meloidogyne incognita, concluding that recent activity of TE in both genic and regulatory regions might have given rise to relevant functional differences between genomes. This was the first estimation of TE activity as a mechanism probably involved in genome plasticity of this root-knot nematode. This study also shed light on evolutionary mechanisms of asexual organisms with an allopolyploid origin. These authors re-annotated the 185 Mb triploid genome of M. incognita for TE content analysis using stringent filters (Kozlowski 2020a), and estimated activity by their distribution using a population genomics approach including isolates from different crops and locations. Canonical TE represented around 4.7% of the M. incognita genome of which mostly correspond to TIR (Terminal Inverted Repeats) and MITEs (Miniature Inverted repeat Transposable Elements) followed by Maverick DNA transposons and LTR (Long Terminal Repeats) retrotransposons. The result that most TE found were represented by DNA transposons is similar to the previous studies with the nematode species model Caenorhabditis elegans (Bessereau 2006; Kozlowski 2020b) and other nematodes as well. Canonical TE annotations were highly similar to their consensus sequences containing transposition machinery when TE are autonomous, whereas no genes involved in transposition were found in non-autonomous ones. These findings suggest recent activity of TE in the M. incognita genome. Other relevant result was the significant variation in TE presence frequencies found in more than 3,500 loci across isolates, following a bimodal distribution within isolates. However, variation in TE frequencies was low to moderate between isolates recapitulating the phylogenetic signal of isolates DNA sequences polymorphisms. A detailed analysis of TE frequencies across isolates allowed identifying polymorphic TE loci, some of which might be neo-insertions mostly of TIRs and MITEs (Kozlowski 2020c). Interestingly, the two thirds of the fixed neo-insertions were located in coding regions or in regulatory regions impacting expression of specific genes in M. incognita. Future research on proteomics is needed to evaluate the functional impact that these insertions have on adaptive evolution in M. incognita. In this line, this pioneer research of Kozlowski et al. (2020) is a first step that is also relevant to remark the role that allopolyploidy and reproduction have had on shaping nematode genomes.

References

[1] Bessereau J-L. 2006. Transposons in C. elegans. WormBook. 10.1895/wormbook.1.70.1

[2] Castagnone-Sereno P, Danchin EGJ. 2014. Parasitic success without sex - the nematode experience. J. Evol. Biol. 27:1323-1333. 10.1111/jeb.12337

[3] Faino L, Seidl MF, Shi-Kunne X, Pauper M, Berg GCM van den, Wittenberg AHJ, Thomma BPHJ. 2016. Transposons passively and actively contribute to evolution of the two-speed genome of a fungal pathogen. Genome Res. 26:1091-1100. 10.1101/gr.204974.116

[4] Glémin S, François CM, Galtier N. 2019. Genome Evolution in Outcrossing vs. Selfing vs. Asexual Species. In: Anisimova M, editor. Evolutionary Genomics: Statistical and Computational Methods. Methods in Molecular Biology. New York, NY: Springer. p. 331-369. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9074-0_11

[5] Koutsovoulos GD, Marques E, Arguel M-J, Duret L, Machado ACZ, Carneiro RMDG, Kozlowski DK, Bailly-Bechet M, Castagnone-Sereno P, Albuquerque EVS, et al. 2020. Population genomics supports clonal reproduction and multiple independent gains and losses of parasitic abilities in the most devastating nematode pest. Evol. Appl. 13:442-457. 10.1111/eva.12881

[6] Kozlowski D. 2020a. Transposable Elements prediction and annotation in the M. incognita genome. Portail Data INRAE. 10.15454/EPTDOS

[7] Kozlowski D. 2020b. Transposable Elements prediction and annotation in the C. elegans genome. Portail Data INRAE. 10.15454/LQCIW0

[8] Kozlowski D. 2020c. TE polymorphisms detection and analysis with PopoolationTE2. Portail Data INRAE. 10.15454/EWJCT8

[9] Kozlowski DK, Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen R, Da Rocha M, Koutsovoulos GD, Bailly-Bechet M, Danchin EG (2020) Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. bioRxiv, 2020.04.30.069948, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. 10.1101/2020.04.30.069948

[10] Savary S, Willocquet L, Pethybridge SJ, Esker P, McRoberts N, Nelson A. 2019. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3:430-439. 10.1038/s41559-018-0793-y

[11] Trudgill DL, Blok VC. 2001. Apomictic, polyphagous root-knot nematodes: exceptionally successful and damaging biotrophic root pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathol 39:53-77. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.39.1.53

| Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita | Djampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin | <p>Despite reproducing without sexual recombination, the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita is adaptive and versatile. Indeed, this species displays a global distribution, is able to parasitize a large range of plants and can overcome plant ... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Ines Alvarez | | 2020-05-04 11:43:14 | View |

Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population

Miguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.080895

Detecting loci under natural selection from temporal genomic data of selfing populations

Recommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

The observed levels of genomic diversity in contemporary populations are the result of changes imposed by several evolutionary processes. Among them, natural selection is known to dramatically shape the genetic diversity of loci associated with phenotypes which affect the fitness of carriers. As such, many efforts have been dedicated towards developing methods to detect signatures of natural selection from genomes of contemporary samples [1].

Recent technological advances made the generation of large-scale genomic data from temporal samples, either from experimental populations or historical or ancient samples, accessible to a wide scientific community [2]. Notably, temporal population genomic data allow for a direct observation and study of how, for instance, allele frequencies change through time in response to evolutionary stimuli. Such information can be exploited to detect loci under natural selection, either via mathematical modelling or by investigating empirical distributions [3].

However, most of current methods to detect selection from temporal genomic data have largely ignored selfing populations, despite the latter comprising a significant proportion of species with social and economic importance. Selfing changes genomic patterns by reducing the effective recombination rate, which makes distinguishing between neutral evolution and natural selection even more challenging than for the case of outcrossing populations [4]. Nevertheless, an outlier-approach based on temporal genomic data for the selfing Arabidopsis thaliana population revealed loci under selection [5].

This study suggested the promise of detecting selection for selfing populations and encouraged further investigations to test the power of selection scans under different mating systems.

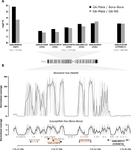

To address this question, Navascués et al. [6] extended a previously proposed approach for temporal genome scan [7] to incorporate partial self-fertilization. In the original implementation [7], it is assumed that, under neutrality, all loci provide levels of genetic differentiation drawn from the same distribution. If some of the loci are under selection, such distribution should show heterogeneity. Navascués et al. [6] proposed a test for the homogeneity between loci-specific and genome-wide differentiation by deriving a null distribution of FST via simulations using SLiM [8]. After filtering for low-frequency variants and correct for multiple tests, authors derived a statistical test for selection and assess its power under a wide range of scenarios of selfing rate, selection coefficient, duration and type of selection [6].

The newly proposed test achieved good performance to distinguish between neutral and selected loci in most tested scenarios.

As expected, the test's performance significantly drops for scenarios of high selfing rates and selection from standing variation. Additionally, the probability to correctly detect selection decreases with increasing distance from the causal variant. Intriguingly, the test showed high power when the selected ancestral allele had an initial low frequency, and when the selected derived allele had a high initial frequency. When applied to a data set of around 1,000 SNPs from the highly selfing Medicago truncatula population, an annual plant of the legume family [9], the test did not provide any candidate loci under selection [6].

In summary, the detection of loci under selection in selfing populations is and largely remains a challenging task even when explictly account for the different mating system. However, recombination events that occurred before the selective pressure allow ancestral beneficial alleles to exhibit a detectable pattern of non-neutrality. As such, in partially selfing populations, the strength of the footprint of selection depends on several factors, mostly on the selfing rate, the time of onset and type of selection.

One major assumption of this study is that the model implies unstructured population and continuity between samples obtained from the same geographical location over time. As such assumptions are typically violated in real populations, further research into the effect of more complex demographic scenarios is desired to fully understand the power to detect selection in selfing populations. Furthermore, more power could be gained by including additional genomic information at each time point. In this context, recent approaches that make full use of genomic data based on deep learning [10] may contribute significantly towards this goal. Similarly, the effect of data filtering on the power to detect selection should be further explored, especially in the context of DNA resequencing experiments. These analyses will help elucidate the power offered by selection scans from temporal genomic data in selfing populations.

References

[1] Stern AJ, Nielsen R (2019) Detecting Natural Selection. In: Handbook of Statistical Genomics , pp. 397–40. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119487845.ch14

[2] Leonardi M, Librado P, Der Sarkissian C, Schubert M, Alfarhan AH, Alquraishi SA, Al-Rasheid KAS, Gamba C, Willerslev E, Orlando L (2017) Evolutionary Patterns and Processes: Lessons from Ancient DNA. Systematic Biology, 66, e1–e29. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syw059

[3] Dehasque M, Ávila‐Arcos MC, Díez‐del‐Molino D, Fumagalli M, Guschanski K, Lorenzen ED, Malaspinas A-S, Marques‐Bonet T, Martin MD, Murray GGR, Papadopulos AST, Therkildsen NO, Wegmann D, Dalén L, Foote AD (2020) Inference of natural selection from ancient DNA. Evolution Letters, 4, 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.165

[4] Vitalis R, Couvet D (2001) Two-locus identity probabilities and identity disequilibrium in a partially selfing subdivided population. Genetics Research, 77, 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016672300004833

[5] Frachon L, Libourel C, Villoutreix R, Carrère S, Glorieux C, Huard-Chauveau C, Navascués M, Gay L, Vitalis R, Baron E, Amsellem L, Bouchez O, Vidal M, Le Corre V, Roby D, Bergelson J, Roux F (2017) Intermediate degrees of synergistic pleiotropy drive adaptive evolution in ecological time. Nature Ecology and Evolution, 1, 1551–1561. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0297-1

[6] Navascués M, Becheler A, Gay L, Ronfort J, Loridon K, Vitalis R (2020) Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population. bioRxiv, 2020.05.06.080895, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.080895

[7] Goldringer I, Bataillon T (2004) On the Distribution of Temporal Variations in Allele Frequency: Consequences for the Estimation of Effective Population Size and the Detection of Loci Undergoing Selection. Genetics, 168, 563–568. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.103.025908

[8] Messer PW (2013) SLiM: Simulating Evolution with Selection and Linkage. Genetics, 194, 1037–1039. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.113.152181

[9] Siol M, Prosperi JM, Bonnin I, Ronfort J (2008) How multilocus genotypic pattern helps to understand the history of selfing populations: a case study in Medicago truncatula. Heredity, 100, 517–525. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2008.5

[10] Sanchez T, Cury J, Charpiat G, Jay F Deep learning for population size history inference: Design, comparison and combination with approximate Bayesian computation. Molecular Ecology Resources, n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13224

| Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population | Miguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis | <p>Tracking genetic changes of populations through time allows a more direct study of the evolutionary processes acting on the population than a single contemporary sample. Several statistical methods have been developed to characterize the demogr... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Matteo Fumagalli | | 2020-05-08 10:34:31 | View |

Evolution of sperm morphology in Daphnia within a phyologenetic context

Recommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Renate Matzke-Karasz and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this study sperm morphology is studied in 15 Daphnia species and the morphological data are mapped on a Daphnia phylogeny. The authors found that despite the internal fertilization mode, Daphnia have among the smallest sperm recorded, as would be expected with external fertilization. The authors also conclude that increase in sperm length has evolved twice, that sperm encapsulation has been lost in a clade, and that this clade has very polymorphic sperm with long, and often numerous, filopodia.

Daphnia is an interesting model to study sperm morphology because the biology of sexual reproduction is often ignored in (cyclical) parthenogenetic species. Daphnia is part of the very diverse and successful group of cladocerans with cyclical parthenogenetic reproduction. The success of this reproduction mode is reflected in the known 620 species that radiated within this order, this is more than half of the known Branchiopod species diversity and the estimated number of cladoceran species is even two to four times higher (Forró et al. 2008). Looking at this particular model with a good phylogeny and some particularity in the mode of fertilization/reproduction, has thus a large value. Most Daphnia species are cyclical parthenogenetic and switch between sexual and asexual reproduction depending on the environmental conditions. Within the genus Daphnia, evolution to obligate asexuality has evolved in at least four independent occasions by three different mechanisms: (i) obligate parthenogenesis through hybridisation with or without polyploidy, (ii) asexuality has been acquired de novo in some populations and (iii) in certain lineages females reproduce by obligate parthenogenesis, whereas the clonally propagated males produce functional haploid sperm that allows them to breed with sexual females of normal cyclically parthenogenetic lineages (more on this in Decaestecker et al. 2009).

This study is made in the context of a body of research on the evolution of one of the most fundamental and taxonomically diverse cell types. There is surprisingly little known about the adaptive value underlying their morphology because it is very difficult to test this experimentally. Studying sperm morphology across species is interesting to study evolution itself because it is a "simple trait". As the authors state: The understanding of the adaptive value of sperm morphology, such as length and shape, remains largely incomplete (Lüpold & Pitnick, 2018). Based on phylogenetic analyses across the animal kingdom, the general rule seems to be that fertilization mode (i.e. whether eggs are fertilized within or outside the female) is a key predictor of sperm length (Kahrl et al., 2021). There is a trade-off between sperm number and length (Immler et al., 2011). This study reports on one of the smallest sperm recorded despite the fertilization being internal. The brood pouch in Daphnia is an interesting particularity as fertilisation occurs internally, but it is not disconnected from the environment. It is also remarkable that there are two independent evolution lines of sperm size in this group. It suggests that those traits have an adaptive value.

References

Decaestecker E, De Meester L, Mergeay J (2009) Cyclical Parthenogenesis in Daphnia: Sexual Versus Asexual Reproduction. In: Lost Sex: The Evolutionary Biology of Parthenogenesis (eds Schön I, Martens K, Dijk P), pp. 295–316. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2770-2_15

Duneau David, Möst M, Ebert D (2022) Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. bioRxiv, 2020.01.31.929414, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929414

Forró L, Korovchinsky NM, Kotov AA, Petrusek A (2008) Global diversity of cladocerans (Cladocera; Crustacea) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia, 595, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-007-9013-5

Immler S, Pitnick S, Parker GA, Durrant KL, Lüpold S, Calhim S, Birkhead TR (2011) Resolving variation in the reproductive tradeoff between sperm size and number. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 5325–5330. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1009059108

Kahrl AF, Snook RR, Fitzpatrick JL (2021) Fertilization mode drives sperm length evolution across the animal tree of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5, 1153–1164. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01488-y

Lüpold S, Pitnick S (2018) Sperm form and function: what do we know about the role of sexual selection? Reproduction, 155, R229–R243. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-17-0536

| Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. | Duneau, David; Moest, Markus; Ebert, Dieter | <p style="text-align: justify;">Sperm is the most fundamental male reproductive feature. It serves the fertilization of eggs and evolves under sexual selection. Two components of sperm are of particular interest, their number and their morphology.... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Morphological Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Ellen Decaestecker | | 2020-05-30 22:54:15 | View |

Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemics in France

Gonché Danesh, Baptiste Elie,Yannis Michalakis, Mircea T. Sofonea, Antonin Bal, Sylvie Behillil, Grégory Destras, David Boutolleau, Sonia Burrel, Anne-Geneviève Marcelin, Jean-Christophe Plantier, Vincent Thibault, Etienne Simon-Loriere, Sylvie van der Werf, Bruno Lina, Laurence Josset, Vincent Enouf, Samuel Alizon and the COVID SMIT PSL group

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.03.20119925

SARS-Cov-2 genome sequence analysis suggests rapid spread followed by epidemic slowdown in France

Recommended by B. Jesse Shapiro based on reviews by Luca Ferretti and 2 anonymous reviewers

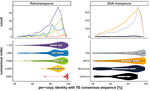

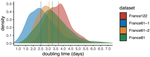

Sequencing and analyzing SARS-Cov-2 genomes in nearly real time has the potential to quickly confirm (and inform) our knowledge of, and response to, the current pandemic [1,2]. In this manuscript [3], Danesh and colleagues use the earliest set of available SARS-Cov-2 genome sequences available from France to make inferences about the timing of the major epidemic wave, the duration of infections, and the efficacy of lockdown measures. Their phylodynamic estimates -- based on fitting genomic data to molecular clock and transmission models -- are reassuringly close to estimates based on 'traditional' epidemiological methods: the French epidemic likely began in mid-January or early February 2020, and spread relatively rapidly (doubling every 3-5 days), with people remaining infectious for a median of 5 days [4,5]. These transmission parameters are broadly in line with estimates from China [6,7], but are currently unknown in France (in the absence of contact tracing data). By estimating the temporal reproductive number (Rt), the authors detected a slowing down of the epidemic in the most recent period of the study, after mid-March, supporting the efficacy of lockdown measures.

Along with the three other reviewers of this manuscript, I was impressed with the careful and exhaustive phylodynamic analyses reported by Danesh et al. [3]. Notably, they take care to show that the major results are robust to the choice of priors and to sampling. The authors are also careful to note that the results are based on a limited sample size of SARS-Cov-2 genomes, which may not be representative of all regions in France. Their analysis also focused on the dominant SARS-Cov-2 lineage circulating in France, which is also circulating in other countries. The variations they inferred in epidemic growth in France could therefore be reflective on broader control policies in Europe, not only those in France. Clearly more work is needed to fully unravel which control policies (and where) were most effective in slowing the spread of SARS-Cov-2, but Danesh et al. [3] set a solid foundation to build upon with more data. Overall this is an exemplary study, enabled by rapid and open sharing of sequencing data, which provides a template to be replicated and expanded in other countries and regions as they deal with their own localized instances of this pandemic.

References

[1] Grubaugh, N. D., Ladner, J. T., Lemey, P., Pybus, O. G., Rambaut, A., Holmes, E. C., & Andersen, K. G. (2019). Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty-first century. Nature microbiology, 4(1), 10-19. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0296-2

[2] Fauver et al. (2020) Coast-to-Coast Spread of SARS-CoV-2 during the Early Epidemic in the United States. Cell, 181(5), 990-996.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.021

[3] Danesh, G., Elie, B., Michalakis, Y., Sofonea, M. T., Bal, A., Behillil, S., Destras, G., Boutolleau, D., Burrel, S., Marcelin, A.-G., Plantier, J.-C., Thibault, V., Simon-Loriere, E., van der Werf, S., Lina, B., Josset, L., Enouf, V. and Alizon, S. and the COVID SMIT PSL group (2020) Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemic in France. medRxiv, 2020.06.03.20119925, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.03.20119925

[4] Salje et al. (2020) Estimating the burden of SARS-CoV-2 in France. hal-pasteur.archives-ouvertes.fr/pasteur-02548181

[5] Sofonea, M. T., Reyné, B., Elie, B., Djidjou-Demasse, R., Selinger, C., Michalakis, Y. and Samuel Alizon, S. (2020) Epidemiological monitoring and control perspectives: application of a parsimonious modelling framework to the COVID-19 dynamics in France. medRxiv, 2020.05.22.20110593. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.22.20110593

[6] Rambaut, A. (2020) Phylogenetic analysis of nCoV-2019 genomes. virological.org/t/phylodynamic-analysis-176-genomes-6-mar-2020/356

[7] Li et al. (2020) Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med, 382: 1199-1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316

| Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemics in France | Gonché Danesh, Baptiste Elie,Yannis Michalakis, Mircea T. Sofonea, Antonin Bal, Sylvie Behillil, Grégory Destras, David Boutolleau, Sonia Burrel, Anne-Geneviève Marcelin, Jean-Christophe Plantier, Vincent Thibault, Etienne Simon-Loriere, Sylvie va... | <p>France was one of the first countries to be reached by the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, we analyse 196 SARS-Cov-2 genomes collected between Jan 24 and Mar 24 2020, and perform a phylodynamics analysis. In particular, we analyse the doubling time, r... |  | Evolutionary Epidemiology, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | B. Jesse Shapiro | | 2020-06-04 13:13:57 | View |

A genomic amplification affecting a carboxylesterase gene cluster confers organophosphate resistance in the mosquito Aedes aegypti: from genomic characterization to high-throughput field detection

Julien Cattel, Chloé Haberkorn, Fréderic Laporte, Thierry Gaude, Tristan Cumer, Julien Renaud, Ian W. Sutherland, Jeffrey C. Hertz, Jean-Marc Bonneville, Victor Arnaud, Camille Noûs, Bénédicte Fustec, Sébastien Boyer, Sébastien Marcombe, Jean-Philippe David

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.139741

Identification of a gene cluster amplification associated with organophosphate insecticide resistance: from the diversity of the resistance allele complex to an efficient field detection assay

Recommended by Stephanie Bedhomme based on reviews by Diego Ayala and 2 anonymous reviewers

The emergence and spread of insecticide resistance compromises the efficiency of insecticides as prevention tool against the transmission of insect-transmitted diseases (Moyes et al. 2017). In this context, the understanding of the genetic mechanisms of resistance and the way resistant alleles spread in insect populations is necessary and important to envision resistance management policies. A common and important mechanism of insecticide resistance is gene amplification and in particular amplification of insecticide detoxification genes, which leads to the overexpression of these genes (Bass & Field, 2011). Cattel and coauthors (2020) adopt a combination of experimental approaches to study the role of gene amplification in resistance to organophosphate insecticides in the mosquito Aedes aegypti and its occurrence in populations of South East Asia and to develop a molecular test to track resistance alleles.

Their first approach consists in performing an artificial selection on laboratory Ae. Aegypti populations started with individuals collected in Laos. In the selected population, an initial 90% mortality by adult exposure to the organophosphate insecticide malathion is imposed. This population shows a steep increase in resistance to malathion and other organophosphate insecticides, which is absent in the paired control population. The transcriptomic patterns of the control and the evolved populations as well as of a reference sensitive population reveals, among other differences, the over-expression of five carboxy/choline esterase (CCE) genes in the insecticide selected population. These five genes happen to be clustered in the Ae. aegypti genome and whole genome sequencing of a highly resistant population combined to qPCR test on genomic DNA showed that the overexpression of these genes is due to gene amplification. Although it would have been more elegant to have replicate selected and control populations and to perform the transcriptomic and the genomic analyses directly on the experimental populations, the authors gather a set of experimental evidence which combined to previous knowledge on the function of the amplified and over-expressed genes and on their implication in organophosphate insecticide resistance in other species allow to discard the possibility that this gene amplification spread by drift in the selected population.

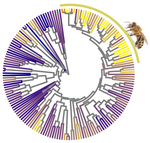

In a second part of the paper, copy number variation for CCE genes is checked in field sample populations. This test reveals the presence of resistance alleles in half of the fourteen South East Asia populations sampled. Very interestingly, it also reveals a high level of complexity and diversity among the resistance alleles: it shows first the existence, both in the experimental and the field populations, of at least two amplified alleles (differing by the number of genes amplified) and second a high variation in the copy number of amplified genes. This indicates that gene amplification as a molecular resistance mechanism has actually lead to a high diversity of resistance alleles. These alleles are likely to differ both by the level of resistance conferred and the fitness cost imposed in the absence of the insecticide and these two values are affecting the evolution of their frequency in the field and ultimately the spread of resistance.

The last part of the paper is devoted to the development of a high-throughput Taqman assay which allows to determine rapidly the copy number of one of the esterase genes amplified in the resistance alleles described earlier. This assay is nicely validated and will definitely be a useful tool to determine the occurrence of these resistance alleles in field population. The fact that it gives access to the copy number will also allow to follow its copy number across time and get insight into the complexity of resistance evolution by gene amplification.

To sum up, this paper studies the implication of carboxy/choline esterase genes amplification in organophosphate resistance evolution in Ae. aegypti, reveals the diversity among individuals and populations of this resistance mechanism, because of variation both in the identity of the genes amplified and in their copy number and sets up a fast and efficient tool to detect and follow the spread of these resistant alleles in the field. Additionally, the different experimental approaches adopted have generated genomic and transcriptomic data, of which only the part related to CCE gene amplification has been exploited. These data are very likely to reveal other genomic and expression determinants of resistance that will give access to an extra degree of complexity in organophosphate insecticide resistance determinism and evolution.

References

Bass C, Field LM (2011) Gene amplification and insecticide resistance. Pest Management Science, 67, 886–890. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2189

Cattel J, Haberkorn C, Laporte F, Gaude T, Cumer T, Renaud J, Sutherland IW, Hertz JC, Bonneville J-M, Arnaud V, Nous C, Fustec B, Boyer S, Marcombe S, David J-P (2020) A genomic amplification affecting a carboxylesterase gene cluster confers organophosphate resistance in the mosquito Aedes aegypti: from genomic characterization to high-throughput field detection. bioRxiv, 2020.06.08.139741, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.139741

Moyes CL, Vontas J, Martins AJ, Ng LC, Koou SY, Dusfour I, Raghavendra K, Pinto J, Corbel V, David J-P, Weetman D (2017) Contemporary status of insecticide resistance in the major Aedes vectors of arboviruses infecting humans. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 11, e0005625. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005625

| A genomic amplification affecting a carboxylesterase gene cluster confers organophosphate resistance in the mosquito Aedes aegypti: from genomic characterization to high-throughput field detection | Julien Cattel, Chloé Haberkorn, Fréderic Laporte, Thierry Gaude, Tristan Cumer, Julien Renaud, Ian W. Sutherland, Jeffrey C. Hertz, Jean-Marc Bonneville, Victor Arnaud, Camille Noûs, Bénédicte Fustec, Sébastien Boyer, Sébastien Marcombe, Jean-Phil... | <p>By altering gene expression and creating paralogs, genomic amplifications represent a key component of short-term adaptive processes. In insects, the use of insecticides can select gene amplifications causing an increased expression of detoxifi... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Experimental Evolution, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Stephanie Bedhomme | | 2020-06-09 13:27:18 | View |

Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mites

Miguel A. Cruz, Sara Magalhães, Élio Sucena, Flore Zélé

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.29.178699

Speciation in spider mites: disentangling the roles of Wolbachia-induced vs. nuclear mating incompatibilities

Recommended by Jan Engelstaedter based on reviews by Wolfgang Miller and 1 anonymous reviewer

Cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) is a mating incompatibility that is induced by maternally inherited endosymbionts in many arthropods. These endosymbionts include, most famously, the alpha-proteobacterium Wolbachia pipientis (Yen & Barr 1971; Werren et al. 2008) but also the Bacteroidetes bacterium Cardinium hertigii (Zchori-Fein et al. 2001), a gamma-proteobacterium of the genus Rickettsiella (Rosenwald et al. 2020) and another, as yet undescribed alpha-proteobacterium (Takano et al. 2017). CI manifests as embryonic mortality in crosses between infected males and females that are uninfected or infected with a different strain, whereas embryos develop normally in all other crosses. This phenotype may enable the endosymbionts to spread rapidly within their host population. Exploiting this, CI-inducing Wolbachia are being harnessed to control insect-borne diseases (e.g., O'Neill 2018). Much progress elucidating the genetic basis and developmental mechanism of CI has been made in recent years, but many open questions remain (Shropshire et al. 2020).

Immediately following the discovery and early study of CI in mosquitoes, Laven (1959, 1967) proposed that CI could be an important driver of speciation. Indeed, bi-directional CI can strongly reduce gene flow between two populations due to the elimination of F1 embryos, so that CI can act as a trigger for genetic differentiation in the host (Telschow et al. 2002, 2005). This idea has received much attention, and a potential role for CI in incipient speciation has been demonstrated in several species (e.g., Bordenstein et al. 2001; Jaenike et al. 2006). However, we still don’t know how commonly CI actually triggers speciation, rather than being merely a minor player or secondary phenomenon. The problem is that in addition to CI, postzygotic reproductive isolation can also be caused by host-induced, nuclear incompatibilities. Determining the relative contributions of these two causes of isolation is difficult and has rarely been done.

The study by Cruz et al. (2020) addresses this problem head-on, using a study system of Tetranychus urticae spider mites. These cosmopolitan mites are infected with different strains of Wolbachia. They come in two different colour forms (red and green) that can co-occur sympatrically on the same host plant but exhibit various degrees of reproductive isolation. A complicating factor in spider mites is that they are haplodiploid: unfertilised eggs develop into haploid males and are therefore not affected by any postzygotic incompatibilities, whereas fertilised eggs normally develop into diploid females. In haplodiploids, Wolbachia-induced CI can either kill diploid embryos (as in diplodiploid species), or turn them into haploid males. In their study, Cruz et al. used three different populations (one of the green and two of the red form) and employed a full factorial experiment involving all possible combinations of crosses of Wolbachia infected or uninfected males and females. For each cross, they measured F1 embryonic and juvenile mortality as well as sex ratio, and they also measured F1 fertility and F2 viability. Their results showed that there is strong reduction in hybrid female production caused by Wolbachia-induced CI. However, independent of this and through a different mechanism, there is an even stronger reduction in hybrid production caused by host-associated incompatibilities. In combination with the also observed near-complete sterility of F1 hybrid females and full F2 hybrid breakdown (neither of which is caused by Wolbachia), the results indicate essentially complete reproductive isolation between the green and red forms of T. urticae.

Overall, this is an elegant study with an admirably clean and comprehensive experimental design. It demonstrates that Wolbachia can contribute to reproductive isolation between populations, but that host-induced mechanisms of reproductive isolation predominate in these spider mite populations. Further studies in this exiting system would be useful that also investigate the contribution of pre-zygotic isolation mechanisms such as assortative mating, ascertain whether the results can be generalised to other populations, and – most challengingly – establish the order in which the different mechanisms of reproductive isolation evolved.

References

Bordenstein, S. R., O'Hara, F. P., and Werren, J. H. (2001). Wolbachia-induced incompatibility precedes other hybrid incompatibilities in Nasonia. Nature, 409(6821), 707-710. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/35055543

Cruz, M. A., Magalhães, S., Sucena, É., and Zélé, F. (2020) Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mites. bioRxiv, 2020.06.29.178699, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.29.178699

Jaenike, J., Dyer, K. A., Cornish, C., and Minhas, M. S. (2006). Asymmetrical reinforcement and Wolbachia infection in Drosophila. PLoS Biol, 4(10), e325. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0040325

Laven, H. (1959). SPECIATION IN MOSQUITOES Speciation by Cytoplasmic Isolation in the Culex Pipiens-Complex. In Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology (Vol. 24, pp. 166-173). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

Laven, H. (1967). A possible model for speciation by cytoplasmic isolation in the Culex pipiens complex. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 37(2), 263-266.

O’Neill S.L. (2018) The Use of Wolbachia by the World Mosquito Program to Interrupt Transmission of Aedes aegypti Transmitted Viruses. In: Hilgenfeld R., Vasudevan S. (eds) Dengue and Zika: Control and Antiviral Treatment Strategies. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 1062. Springer, Singapore. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8727-1_24

Rosenwald, L.C., Sitvarin, M.I. and White, J.A. (2020). Endosymbiotic Rickettsiella causes cytoplasmic incompatibility in a spider host. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.1107

Shropshire, J. D., Leigh, B., and Bordenstein, S. R. (2020). Symbiont-mediated cytoplasmic incompatibility: what have we learned in 50 years?. Elife, 9, e61989. doi: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.61989

Takano et al. (2017). Unique clade of alphaproteobacterial endosymbionts induces complete cytoplasmic incompatibility in the coconut beetle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(23), 6110-6115. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1618094114

Telschow, A., Hammerstein, P., and Werren, J. H. (2002). The effect of Wolbachia on genetic divergence between populations: models with two-way migration. the american naturalist, 160(S4), S54-S66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/342153

Telschow, A., Hammerstein, P., and Werren, J. H. (2005). The effect of Wolbachia versus genetic incompatibilities on reinforcement and speciation. Evolution, 59(8), 1607-1619. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2005.tb01812.x

Werren, J. H., Baldo, L., and Clark, M. E. (2008). Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 6(10), 741-751. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1969

Yen, J. H., and Barr, A. R. (1971). New hypothesis of the cause of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Culex pipiens L. Nature, 232(5313), 657-658. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/232657a0

Zchori-Fein, E., Gottlieb, Y., Kelly, S. E., Brown, J. K., Wilson, J. M., Karr, T. L., and Hunter, M. S. (2001). A newly discovered bacterium associated with parthenogenesis and a change in host selection behavior in parasitoid wasps. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(22), 12555-12560. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.221467498

| Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mites | Miguel A. Cruz, Sara Magalhães, Élio Sucena, Flore Zélé | <p>Wolbachia are widespread maternally-inherited bacteria suggested to play a role in arthropod host speciation through induction of cytoplasmic incompatibility, but this hypothesis remains controversial. Most studies addressing Wolbachia-induced ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Hybridization / Introgression, Life History, Reproduction and Sex, Speciation, Species interactions | Jan Engelstaedter | | 2020-07-09 10:18:28 | View |

Review and Assessment of Performance of Genomic Inference Methods based on the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent

Recommended by Stephan Schiffels based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

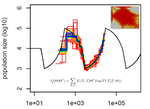

The human genome not only encodes for biological functions and for what makes us human, it also encodes the population history of our ancestors. Changes in past population sizes, for example, affect the distribution of times to the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of genomic segments, which in turn can be inferred by sophisticated modelling along the genome.

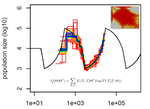

A key framework for such modelling of local tMRCA tracts along genomes is the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (SMC) (McVean and Cardin 2005, Marjoram and Wall 2006) . The problem that the SMC solves is that the mosaic of local tMRCAs along the genome is unknown, both in their actual ages and in their positions along the genome. The SMC allows to effectively sum across all possibilities and handle the uncertainty probabilistically. Several important tools for inferring the demographic history of a population have been developed built on top of the SMC, including PSMC (Li and Durbin 2011), diCal (Sheehan et al 2013), MSMC (Schiffels and Durbin 2014), SMC++ (Terhorst et al 2017), eSMC (Sellinger et al. 2020) and others.

In this paper, Sellinger, Abu Awad and Tellier (2020) review these SMC-based methods and provide a coherent simulation design to comparatively assess their strengths and weaknesses in a variety of demographic scenarios (Sellinger, Abu Awad and Tellier 2020). In addition, they used these simulations to test how breaking various key assumptions in SMC methods affects estimates, such as constant recombination rates, or absence of false positive SNP calls.

As a result of this assessment, the authors not only provide practical guidance for researchers who want to use these methods, but also insights into how these methods work. For example, the paper carefully separates sources of error in these methods by observing what they call “Best-case convergence” of each method if the data behaves perfectly and separating that from how the method applies with actual data. This approach provides a deeper insight into the methods than what we could learn from application to genomic data alone.

In the age of genomics, computational tools and their development are key for researchers in this field. All the more important is it to provide the community with overviews, reviews and independent assessments of such tools. This is particularly important as sometimes the development of new methods lacks primary visibility due to relevant testing material being pushed to Supplementary Sections in papers due to space constraints. As SMC-based methods have become so widely used tools in genomics, I think the detailed assessment by Sellinger et al. (2020) is timely and relevant.

In conclusion, I recommend this paper because it bridges from a mere review of the different methods to an in-depth assessment of performance, thereby addressing both beginners in the field who just seek an initial overview, as well as experienced researchers who are interested in theoretical boundaries and assumptions of the different methods.

References

[1] Li, H., and Durbin, R. (2011). Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature, 475(7357), 493-496. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10231

[2] Marjoram, P., and Wall, J. D. (2006). Fast"" coalescent"" simulation. BMC genetics, 7(1), 16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-7-16

[3] McVean, G. A., and Cardin, N. J. (2005). Approximating the coalescent with recombination. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 360(1459), 1387-1393. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2005.1673

[4] Schiffels, S., and Durbin, R. (2014). Inferring human population size and separation history from multiple genome sequences. Nature genetics, 46(8), 919-925. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3015

[5] Sellinger, T. P. P., Awad, D. A., Moest, M., and Tellier, A. (2020). Inference of past demography, dormancy and self-fertilization rates from whole genome sequence data. PLoS Genetics, 16(4), e1008698. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008698

[6] Sellinger, T. P. P., Awad, D. A. and Tellier, A. (2020) Limits and Convergence properties of the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent. bioRxiv, 2020.07.23.217091, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.23.217091

[7] Sheehan, S., Harris, K., and Song, Y. S. (2013). Estimating variable effective population sizes from multiple genomes: a sequentially Markov conditional sampling distribution approach. Genetics, 194(3), 647-662. doi: https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.112.149096

[8] Terhorst, J., Kamm, J. A., and Song, Y. S. (2017). Robust and scalable inference of population history from hundreds of unphased whole genomes. Nature genetics, 49(2), 303-309. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3748

| Limits and Convergence properties of the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent | Thibaut Sellinger, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier | <p>Many methods based on the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (SMC) have been and are being developed. These methods make use of genome sequence data to uncover population demographic history. More recently, new methods have extended the original... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics | Stephan Schiffels | Anonymous | 2020-07-25 10:54:48 | View |

based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers