Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

05 Jun 2018

Pleistocene climate change and the formation of regional species poolsJoaquín Calatayud, Miguel Á. Rodríguez, Rafael Molina-Venegas, María Leo, José Luís Hórreo, Joaquín Hortal https://doi.org/10.1101/149617Recent assembly of European biogeographic species poolRecommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersBiodiversity is unevenly distributed over time, space and the tree of life [1]. The fact that regions are richer than others as exemplified by the latitudinal diversity gradient has fascinated biologists as early as the first explorers travelled around the world [2]. Provincialism was one of the first general features of land biotic distributions noted by famous nineteenth century biologists like the phytogeographers J.D. Hooker and A. de Candolle, and the zoogeographers P.L. Sclater and A.R. Wallace [3]. When these explorers travelled among different places, they were struck by the differences in their biotas (e.g. [4]). The limited distributions of distinctive endemic forms suggested a history of local origin and constrained dispersal. Much biogeographic research has been devoted to identifying areas where groups of organisms originated and began their initial diversification [3]. Complementary efforts found evidence of both historical barriers that blocked the exchange of organisms between adjacent regions and historical corridors that allowed dispersal between currently isolated regions. The result has been a division of the Earth into a hierarchy of regions reflecting patterns of faunal and floral similarities (e.g. regions, subregions, provinces). Therefore a first ensuing question is: “how regional species pools have been assembled through time and space?”, which can be followed by a second question: “what are the ecological and evolutionary processes leading to differences in species richness among species pools?”. To address these questions, the study of Calatayud et al. [5] developed and performed an interesting approach relying on phylogenetic data to identify regional and sub-regional pools of European beetles (using the iconic ground beetle genus Carabus). Specifically, they analysed the processes responsible for the assembly of species pools, by comparing the effects of dispersal barriers, niche similarities and phylogenetic history. They found that Europe could be divided in seven modules that group zoogeographically distinct regions with their associated faunas, and identified a transition zone matching the limit of the ice sheets at Last Glacial Maximum (19k years ago). Deviance of species co-occurrences across regions, across sub-regions and within each region was significantly explained, primarily by environmental niche similarity, and secondarily by spatial connectivity, except for northern regions. Interestingly, southern species pools are mostly separated by dispersal barriers, whereas northern species pools are mainly sorted by their environmental niches. Another important finding of Calatayud et al. [5] is that most phylogenetic structuration occurred during the Pleistocene, and they show how extreme recent historical events (Quaternary glaciations) can profoundly modify the composition and structure of geographic species pools, as opposed to studies showing the role of deep-time evolutionary processes. The study of biogeographic assembly of species pools using phylogenies has never been more exciting and promising than today. Catalayud et al. [5] brings a nice study on the importance of Pleistocene glaciations along with geographical barriers and niche-based processes in structuring the regional faunas of European beetles. The successful development of powerful analytical tools in recent years, in conjunction with the rapid and massive increase in the availability of biological data (including molecular phylogenies, fossils, georeferrenced occurrences and ecological traits), will allow us to disentangle complex evolutionary histories. Although we still face important limitations in data availability and methodological shortcomings, the last decade has witnessed an improvement of our understanding of how historical and biotic triggers are intertwined on shaping the Earth’s stupendous biological diversity. I hope that the Catalayud et al.’s approach (and analytical framework) will help movement in that direction, and that it will provide interesting perspectives for future investigations of other regions. Applied to a European beetle radiation, they were able to tease apart the relative contributions of biotic (niche-based processes) versus abiotic (geographic barriers and climate change) factors. References [1] Rosenzweig ML. 1995. Species diversity in space and time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. | Pleistocene climate change and the formation of regional species pools | Joaquín Calatayud, Miguel Á. Rodríguez, Rafael Molina-Venegas, María Leo, José Luís Hórreo, Joaquín Hortal | <p>Despite the description of bioregions dates back from the origin of biogeography, the processes originating their associated species pools have been seldom studied. Ancient historical events are thought to play a fundamental role in configuring... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography | Fabien Condamine | 2017-06-14 07:30:32 | View | |

02 Jan 2019

Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by EricaMichael D. Pirie, Martha Kandziora, Nicolai M. Nuerk, Nicholas C. Le Maitre, Ana Laura Mugrabi de Kuppler, Berit Gehrke, Edward G.H. Oliver, and Dirk U. Bellstedt https://doi.org/10.1101/290791The colonization history of largely isolated habitatsRecommended by Andrea S. Meseguer based on reviews by Simon Joly, Florian Boucher and 2 anonymous reviewersThe build-up of biodiversity is the result of in situ speciation and immigration, with the interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability determining the probability of an organism to establish in a new area. The relative contribution of these factors have long interested biogeographers, in particular to explain the distribution of organisms adapted to habitats that remained largely isolated, such as the colonization of oceanic islands or land waters. The focus of this study is the formation of the afrotemperate flora; patches of temperate vegetation separated by thousands of kilometers in Africa, with high levels of endemism described in the Cape region, the Drakensberg range and the high mountains of tropical east Africa [1]. The floristic affinities between these centers of endemism have frequently been explored but the origin of many afrotemperate lineages remains enigmatic [2]. References [1] Linder, H.P. 1990. On the relationship between the vegetation and floras of the Afromontane and the Cape regions of Africa. Mitteilungen aus dem Institut für Allgemeine Botanik Hamburg 23b:777–790. | Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by Erica | Michael D. Pirie, Martha Kandziora, Nicolai M. Nuerk, Nicholas C. Le Maitre, Ana Laura Mugrabi de Kuppler, Berit Gehrke, Edward G.H. Oliver, and Dirk U. Bellstedt | <p>The coincidence of long distance dispersal and biome shift is assumed to be the result of a multifaceted interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability of source and sink areas. Here, we test the influence of these factors o... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography | Andrea S. Meseguer | 2018-04-09 10:10:04 | View | |

23 Feb 2024

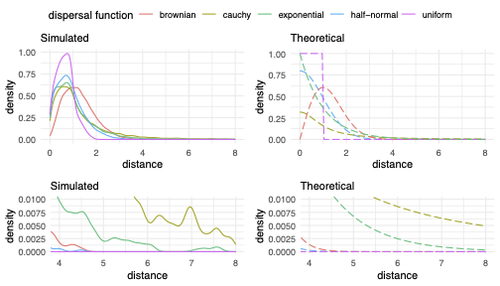

Exploring the effects of ecological parameters on the spatial structure of genetic tree sequencesMariadaria K. Ianni-Ravn, Martin Petr, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.27.534388Disentangling the impact of mating and competition on dispersal patternsRecommended by Diego Ortega-Del Vecchyo based on reviews by Anthony Wilder Wohns, Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewersSpatial population genetics is a field that studies how different evolutionary processes shape geographical patterns of genetic variation. This field is currently hampered by the lack of a deep understanding of the impact of different evolutionary processes shaping the genetic diversity observed across a continuous space (Bradburd and Ralph 2019). Luckily, the recent development of slendr (Petr et al. 2023), which uses the simulator SLiM (Haller and Messer 2023), provides a powerful tool to perform simulations to analyze the impact of different evolutionary parameters on spatial patterns of genetic variation. Here, Ianni-Ravn, Petr, and Racimo 2023 present a series of well-designed simulations to study how three evolutionary factors (dispersal distance, competition distance, and mate choice distance) shape the geographical structure of genealogies. The authors model the dispersal distance between parents and their offspring using five different distributions. Then, the authors perform simulations and they contrast the correspondence between the distribution of observed parent-offspring distances (called DD in the paper) and the distribution used in the simulations (called DF). The authors observe a reasonable correspondence between DF and DD. The authors then show that the competition distance, which decreases the fitness of individuals due to competition for resources if the individuals are close to each other, has small effects on the differences between DD and DF. In contrast, the mate choice distance (which specifies how far away can a parent go to choose a mate) causes discrepancies between DD and DF. When the mate choice distance is small, the individuals tend to cluster close to each other. Overall, these results show that the observed distances between parents and offspring are dependent on the three parameters inspected (dispersal distance, competition distance, and mate choice distance) and make the case that further ecological knowledge of each of these parameters is important to determine the processes driving the dispersal of individuals across geographical space. Based on these results, the authors argue that an “effective dispersal distance” parameter, which takes into account the impact of mate choice distance and dispersal distance, is more prone to be inferred from genetic data. The authors also assess our ability to estimate the dispersal distance using genealogical data in a scenario where the mating distance has small effects on the dispersal distance. Interestingly, the authors show that accurate estimates of the dispersal distance can be obtained when using information from all the parents and offspring going from the present back to the coalescence of all the individuals to the most recent common ancestor. On the other hand, the estimates of the dispersal distance are underestimated when less information from the parent-offspring relationships is used to estimate the dispersal distance. This paper shows the importance of considering mating patterns and the competition for resources when analyzing the dispersal of individuals. The analysis performed by the authors backs up this claim with carefully designed simulations. I recommend this preprint because it makes a strong case for the consideration of ecological factors when analyzing the structure of genealogies and the dispersal of individuals. Hopefully more studies in the future will continue to use simulations and to develop analytical theory to understand the importance of various ecological processes driving spatial genetic variation changes. Bradburd, Gideon S., and Peter L. Ralph. 2019. “Spatial Population Genetics: It’s About Time.” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 50 (1): 427–49. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-022659. Haller, Benjamin C., and Philipp W. Messer. 2023. “SLiM 4: Multispecies Eco-Evolutionary Modeling.” The American Naturalist 201 (5): E127–39. https://doi.org/10.1086/723601. Ianni-Ravn, Mariadaria K., Martin Petr, and Fernando Racimo. 2023. “Exploring the Effects of Ecological Parameters on the Spatial Structure of Genealogies.” bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.27.534388. Petr, Martin, Benjamin C. Haller, Peter L. Ralph, and Fernando Racimo. 2023. “Slendr: A Framework for Spatio-Temporal Population Genomic Simulations on Geographic Landscapes.” Peer Community Journal 3 (e121). https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.354. | Exploring the effects of ecological parameters on the spatial structure of genetic tree sequences | Mariadaria K. Ianni-Ravn, Martin Petr, Fernando Racimo | <p>Geographic space is a fundamental dimension of evolutionary change, determining how individuals disperse and interact with each other. Consequently, space has an important influence on the structure of genealogies and the distribution of geneti... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Diego Ortega-Del Vecchyo | 2023-03-31 18:21:02 | View | |

16 Mar 2023

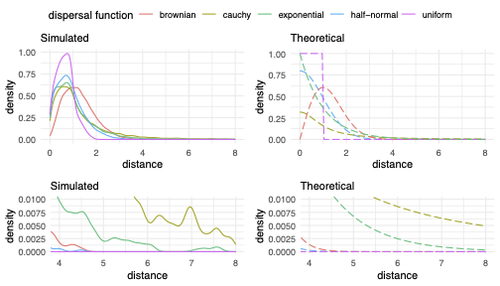

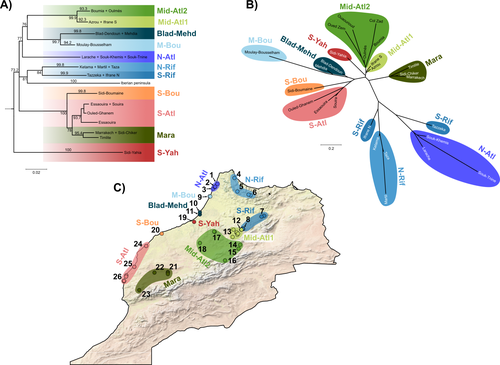

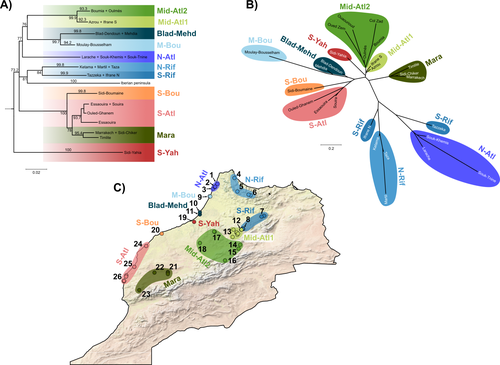

Phylogeographic breaks and how to find them: Separating vicariance from isolation by distance in a lizard with restricted dispersalLoïs Rancilhac, Aurélien Miralles, Philippe Geniez, Daniel Mendez-Arranda, Menad Beddek, José Carlos Brito, Raphaël Leblois, Pierre-André Crochet https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.30.510256The difficult task of partitioning the effects of vicariance and isolation by distance in poor dispersersRecommended by Eric Pante based on reviews by Kevin Sánchez and Aglaia (Cilia) Antoniou based on reviews by Kevin Sánchez and Aglaia (Cilia) Antoniou

Partitioning the effects of vicariance and low dispersal has been a long-standing problem in historical biogeography and phylogeography. While the term “vicariance” refers to divergence in allopatry, caused by some physical (geological, geographical) or climatic barriers (e.g. Rosen 1978), isolation by distance refers to the genetic differentiation of remote populations due to the physical distance separating them, when the latter surpasses the scale of dispersal (Wright 1938, 1940, 1943). Vicariance and dispersal have long been considered as separate forces leading to separate scenarii of speciation (e.g. reviewed in Hickerson and Meyer 2008). Nevertheless, these two processes are strongly linked, as, for example, vicariance theory relies on the assumption that ancestral lineages were once linked by dispersal prior to physical or climatic isolation (Rosen 1978). Low dispersal and vicariance are not mutually exclusive, and distinguishing these two processes in heterogeneous landscapes, especially for poor dispersers, remains therefore a severe challenge. For example, low dispersal (and/or small population size) can give rise to geographic patterns consistent with a phylogeographic break and be mistaken for geographic isolation (Irwin 2002, Kuo and Avise 2005). The study of Rancilliac and colleagues (2023) is at the heart of this issue. It focuses on a nominal lizard species, the red-tailed spiny-footed lizard (Acanthodactylus erythrurus, Squamata: Lacertidae), which has a wide spatial distribution (from the Maghreb to the Iberian Peninsula), is found in a variety of different habitats, and has a wide range of morphological traits that do not always correlate with phylogeny. The main question is the following: have “the morphological and ecological diversification of this group been produced by vicariance and lineage diversification, or by local adaptation in the face of historical gene flow?” To tackle this question, the authors used sequence data from multiple mitochondrial and nuclear markers and a nested analysis workflow integrating phylogeography, multiple correspondence analyses and a relatively novel approach to IBD testing (Hausdorf & Henning, 2020). The latter is based on regression analysis and was shown to be less prone to error than the traditional (partial) Mantel test. While this set of methods allowed the partitioning of the effect of isolation by distance and vicariance in shaping contemporary genetic diversity in red-tailed spiny-footed lizards, some of the evolutionary history of this species complex remains blurred by ongoing gene flow and admixture, retention of ancestral polymorphism, or selection. The lack of congruence between mitochondrial and nuclear gene trees once again warns us that proposing evolutionary scenarii based on individual gene trees is a risky business. References Hausdorf B, Hennig C (2020) Species delimitation and geography. Molecular Ecology Resources, 20, 950–960. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13184 Hickerson MJ, Meyer CP (2008) Testing comparative phylogeographic models of marine vicariance and dispersal using a hierarchical Bayesian approach. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 8, 322. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-8-322 Irwin DE (2002) Phylogeographic breaks without geographic barriers to gene flow. Evolution, 56, 2383–2394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00164.x Kuo C-H, Avise JC (2005) Phylogeographic breaks in low-dispersal species: the emergence of concordance across gene trees. Genetica, 124, 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10709-005-2095-y Rancilhac L, Miralles A, Geniez P, Mendez-Aranda D, Beddek M, Brito JC, Leblois R, Crochet P-A (2023) Phylogeographic breaks and how to find them: An empirical attempt at separating vicariance from isolation by distance in a lizard with restricted dispersal. bioRxiv, 2022.09.30.510256, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.30.510256 Rosen DE (1978) Vicariant Patterns and Historical Explanation in Biogeography. Systematic Biology, 27, 159–188. https://doi.org/10.2307/2412970 Wright, S (1938) Size of population and breeding structure in relation to evolution. Science 87:430-431. Wright S (1940) Breeding Structure of Populations in Relation to Speciation. The American Naturalist, 74, 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1086/280891 Wright S (1943) Isolation by distance. Genetics, 28, 114–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/28.2.114 | Phylogeographic breaks and how to find them: Separating vicariance from isolation by distance in a lizard with restricted dispersal | Loïs Rancilhac, Aurélien Miralles, Philippe Geniez, Daniel Mendez-Arranda, Menad Beddek, José Carlos Brito, Raphaël Leblois, Pierre-André Crochet | <p>Aim</p> <p>Discontinuity in the distribution of genetic diversity (often based on mtDNA) is usually interpreted as evidence for phylogeographic breaks, underlying vicariant units. However, a misleading signal of phylogeographic break can arise... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation, Systematics / Taxonomy | Eric Pante | Kevin Sánchez | 2022-10-05 13:11:28 | View |

26 Oct 2021

Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North AfricaOlvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tournant L., Gazel F., Mody K., Khachtib Y., Roman A., Ursu T.M., Zakharov I.A., Belcram H., Harry M., Roth M., Simon J.C., Oram S., Ricard J.M., Agnello A., Beers E. H., Engelman J., Balti I., Salhi-Hannachi A., Zhang H., Tu H., Mottet C., Barrès B., Degra... https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.11.421644The evolutionary puzzle of the host-parasite-endosymbiont Russian doll for apples and aphidsRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewerEach individual multicellular organism, each of our bodies, is a small universe. Every living surface -skin, cuticle, bark, mucosa- is the home place to milliards of bacteria, fungi and viruses. They constitute our microbiota. Some of them are essential for certain organisms. Other could not live without their hosts. For many species, the relationship between host and microbiota is so close that their histories are inseparable. The recognition of this biological inextricability has led to the notion of holobiont as the organism ensemble of host and microbiota. When individuals of a particular animal or plant species expand their geographical range, it is the holobiont that expands. And these processes of migration, expansion and colonization are often accompanied by evolutionary and ecological innovations in the interspecies relationships, at the macroscopic level (e.g. novel predator-prey or host-parasite interactions) and at the microscopic level (e.g. changes in the microbiota composition). From the human point of view, these novel interactions can be economically disastrous if they involve and threaten important crop or cattle species. And this is especially worrying in the present context of genetic standardization and intensification for mass-production on the one hand, and of climate change on the other. With this perspective, the international team led by Amandine Cornille presents a study aiming at understanding the evolutionary history of the rosy apple aphid Dysaphis plantaginea Passerini, a major pest of the cultivated apple tree Malus domestica Borkh (1). The apple tree was probably domesticated in Central Asia, and later disseminated by humans over the world in different waves, and it was probably introduced in Europe by the Greeks. It is however unclear when and where D. plantaginea started parasitizing the cultivated apple tree. The ancestral D. plantaginea could have already infected the wild ancestor of current cultivated apple trees, but the aphid is not common in Central Asia. Alternatively, it may have gained access only later to the plant, possibly via a host jump, from Pyrus to Malus that may have occurred in Asia Minor or in the Caucasus. In the present preprint, Olvera-Vázquez and coworkers have analysed over 650 D. plantaginea colonies from 52 orchards in 13 countries, in Western, Central and Eastern Europe as well as in Morocco and the USA. The authors have analysed the genetic diversity in the sampled aphids, and have characterized as well the composition of the associated endosymbiont bacteria. The analyses detect substantial recent admixture, but allow to identify aphid subpopulations slightly but significantly differentiated and isolated by distance, especially those in Morocco and the USA, as well as to determine the presence of significant gene flow. This process of colonization associated to gene flow is most likely indirectly driven by human interactions. Very interestingly, the data show that this genetic diversity in the aphids is not reflected by a corresponding diversity in the associated microbiota, largely dominated by a few Buchnera aphidicola variants. In order to determine polarity in the evolutionary history of the aphid-tree association, the authors have applied approximate Bayesian computing and machine learning approaches. Albeit promising, the results are not sufficiently robust to assess directionality nor to confidently assess the origin of the crop pest. Despite the large effort here communicated, the authors point to the lack of sufficient data (in terms of aphid isolates), especially originating from Central Asia. Such increased sampling will need to be implemented in the future in order to elucidate not only the origin and the demographic history of the interaction between the cultivated apple tree and the rosy apple aphid. This knowledge is needed to understand how this crop pest struggles with the different seasonal and geographical selection pressures while maintaining high genetic diversity, conspicuous gene flow, differentiated populations and low endosymbiontic diversity. References

| Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North Africa | Olvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tour... | <p style="text-align: justify;">With frequent host shifts involving the colonization of new hosts across large geographical ranges, crop pests are good models for examining the mechanisms of rapid colonization. The microbial partners of pest insec... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics, Species interactions | Ignacio Bravo | 2020-12-11 19:22:54 | View | |

09 Dec 2019

Systematics and geographical distribution of Galba species, a group of cryptic and worldwide freshwater snailsPilar Alda, Manon Lounnas, Antonio Alejandro Vázquez, Rolando Ayaqui, Manuel Calvopina, Maritza Celi-Erazo, Robert Dillon, Luisa Carolina González Ramírez, Eric S. Loker, Jenny Muzzio-Aroca, Alberto Orlando Nárvaez, Oscar Noya, Andrés Esteban Pereira, Luiggi Martini Robles, Richar Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Nelson Uribe, Patrice David, Philippe Jarne, Jean-Pierre Pointier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès https://doi.org/10.1101/647867The challenge of delineating species when they are hiddenRecommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by Pavel Matos, Christelle Fraïsse and Niklas WahlbergThe science of naming species (taxonomy) has been renewed with the developments of molecular sequencing, digitization of museum specimens, and novel analytical tools. However, naming species can be highly subjective, sometimes considered as an art [1], because it is based on human-based criteria that vary among taxonomists. Nonetheless, taxonomists often argue that species names are hypotheses, which are therefore testable and refutable as new evidence is provided. This challenge comes with a more and more recognized and critical need for rigorously delineated species not only for producing accurate species inventories, but more importantly many questions in evolutionary biology (e.g. speciation), ecology (e.g. ecosystem structure and functioning), conservation biology (e.g. targeting priorities) or biogeography (e.g. diversification processes) depend in part on those species inventories and our knowledge of species [2-3]. Inaccurate species boundaries or diversity estimates may lead us to deliver biased answers to those questions, exactly as phylogenetic trees must be reconstructed rigorously and analyzed critically because they are a first step toward discussing broader questions [2-3]. In this context, biological diversity needs to be studied from multiple and complementary perspectives requiring the collaboration of morphologists, molecular biologists, biogeographers, and modelers [4-5]. Integrative taxonomy has been proposed as a solution to tackle the challenge of delimiting species [2], especially in highly diverse and undocumented groups of organisms. References [1] Ohl, M. (2018). The art of naming. MIT Press. | Systematics and geographical distribution of Galba species, a group of cryptic and worldwide freshwater snails | Pilar Alda, Manon Lounnas, Antonio Alejandro Vázquez, Rolando Ayaqui, Manuel Calvopina, Maritza Celi-Erazo, Robert Dillon, Luisa Carolina González Ramírez, Eric S. Loker, Jenny Muzzio-Aroca, Alberto Orlando Nárvaez, Oscar Noya, Andrés Esteban Pere... | <p>Cryptic species can present a significant challenge to the application of systematic and biogeographic principles, especially if they are invasive or transmit parasites or pathogens. Detecting cryptic species requires a pluralistic approach in ... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Systematics / Taxonomy | Fabien Condamine | Pavel Matos, Christelle Fraïsse | 2019-05-25 10:34:57 | View |

12 Nov 2020

Limits and Convergence properties of the Sequentially Markovian CoalescentThibaut Sellinger, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.23.217091Review and Assessment of Performance of Genomic Inference Methods based on the Sequentially Markovian CoalescentRecommended by Stephan Schiffels based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

The human genome not only encodes for biological functions and for what makes us human, it also encodes the population history of our ancestors. Changes in past population sizes, for example, affect the distribution of times to the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of genomic segments, which in turn can be inferred by sophisticated modelling along the genome. References [1] Li, H., and Durbin, R. (2011). Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature, 475(7357), 493-496. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10231 | Limits and Convergence properties of the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent | Thibaut Sellinger, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier | <p>Many methods based on the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (SMC) have been and are being developed. These methods make use of genome sequence data to uncover population demographic history. More recently, new methods have extended the original... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics | Stephan Schiffels | Anonymous | 2020-07-25 10:54:48 | View |

04 Sep 2019

The discernible and hidden effects of clonality on the genotypic and genetic states of populations: improving our estimation of clonal ratesSolenn Stoeckel, Barbara Porro, Sophie Arnaud-Haond https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.09365v4How to estimate clonality from genetic data: use large samples and consider the biology of the speciesRecommended by Myriam Heuertz based on reviews by David Macaya-Sanz, Marcela Van Loo and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by David Macaya-Sanz, Marcela Van Loo and 1 anonymous reviewer

Population geneticists frequently use the genetic and genotypic information of a population sample of individuals to make inferences on the reproductive system of a species. The detection of clones, i.e. individuals with the same genotype, can give information on whether there is clonal (vegetative) reproduction in the species. If clonality is detected, population geneticists typically use genotypic richness R, the number of distinct genotypes relative to the sample size, to estimate the rate of clonality c, which can be defined as the proportion of reproductive events that are clonal. Estimating the rate of clonality based on genotypic richness is however problematic because, to date, there is no analytical, nor simulation-based, characterization of this relationship. Furthermore, the effect of sampling on this relationship has never been critically examined. References [1] Stoeckel, S., Porro, B., and Arnaud-Haond, S. (2019). The discernible and hidden effects of clonality on the genotypic and genetic states of populations: improving our estimation of clonal rates. ArXiv:1902.09365 [q-Bio] v4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1902.09365v4 | The discernible and hidden effects of clonality on the genotypic and genetic states of populations: improving our estimation of clonal rates | Solenn Stoeckel, Barbara Porro, Sophie Arnaud-Haond | <p>Partial clonality is widespread across the tree of life, but most population genetics models are conceived for exclusively clonal or sexual organisms. This gap hampers our understanding of the influence of clonality on evolutionary trajectories... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Myriam Heuertz | 2019-02-28 10:10:56 | View | |

14 Dec 2023

Genetic sex determination in three closely related hydrothermal vent gastropods, including one species with intersex individualsCastel J, Pradillon F, Cueff V, Leger G, Daguin-Thiébaut C, Ruault S, Mary J, Hourdez S, Jollivet D, and Broquet T https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.11.536409A shared XY sex chromosome system with variable recombination ratesRecommended by Tanja Schwander based on reviews by Hugo Darras, Daniel Jeffries and 1 anonymous reviewerMany species with separate sexes have evolved sex chromosomes, with the sex-limited chromosomes (i.e. the Y or W chromosomes) exhibiting a wide range of genetic divergences from their homologous X or Z chromosomes (Bachtrog et al., 2014). Variable divergences can result from the cessation of recombination between sex chromosomes that occurred at different time points, with the mechanisms of initiation and expansion of recombination suppression along sex chromosomes remaining poorly understood (Charlesworth, 2017). The study by Castel et al (2023) describes the serendipitous discovery of a shared XY sex chromosome system in three closely related hydrothermal vent gastropods. The X and Y chromosomes appear to still recombine but at variable rates across the three species. This variation makes the gastropod system a very promising focus for future research on sex chromosome evolution. An additional intriguing finding is that some females in one of three gastropod species contain male reproductive tissue in their gonads, providing a fascinating case of a mixed or transitory sexual system. Overall, the study by Castel et al (2023) offers the first insights into the reproduction and sex chromosome system of animals living in deep marine vents, which have remained poorly studied and open outstanding research perspectives on these creatures. References Bachtrog, D., J.E.Mank, C.L.Peichel, M.Kirkpatrick, S.P.Otto, T.L. Ashman, M.W.Hahn, J.Kitano, I.Mayrose, R.Ming, et al. 2014.Sex determination: why so many ways of doing it? PLoSBiol. 12:e1001899. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001899 Charlesworth, D. Young sex chromosomes in plants and animals. 2019. New Phytologist 224: 1095–1107. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16002 Castel J, Pradillon F, Cueff V, Leger G, Daguin-Thiébaut C, Ruault S, Mary J, Hourdez S, Jollivet D, and Broquet T 2023. Genetic sex determination in three closely related hydrothermal vent gastropods, including one species with intersex individuals. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.11.536409 | Genetic sex determination in three closely related hydrothermal vent gastropods, including one species with intersex individuals | Castel J, Pradillon F, Cueff V, Leger G, Daguin-Thiébaut C, Ruault S, Mary J, Hourdez S, Jollivet D, and Broquet T | <p style="text-align: justify;">Molluscs have a wide variety of sexual systems and have undergone many transitions from separate sexes to hermaphroditism or vice versa, which is of interest for studying the evolution of sex determination and diffe... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Tanja Schwander | 2023-04-14 11:48:25 | View | |

25 Jan 2023

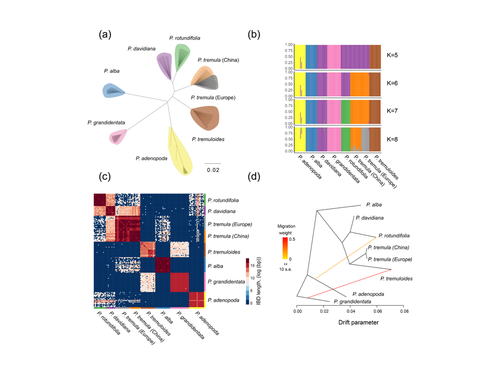

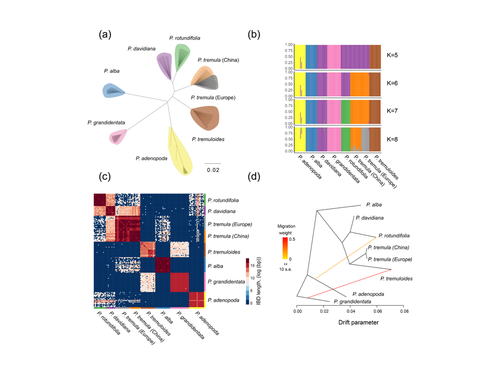

Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradientHuiying Shang, Martha Rendón-Anaya, Ovidiu Paun, View David L Field, Jaqueline Hess, Claus Vogl, Jianquan Liu, Pär K. Ingvarsson, Christian Lexer, Thibault Leroy https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.26.457771Shedding light on genomic divergence along the speciation continuumRecommended by Violaine Llaurens based on reviews by Camille Roux, Steven van Belleghem and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Camille Roux, Steven van Belleghem and 1 anonymous reviewer

The article “Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient” by Shang et al. describes an amazing dataset where genomic variations among 21 pairs of diverging poplar species are compared. Such comparisons are still quite rare and are needed to shed light on the processes shaping genomic divergence along the speciation gradient. Relying on two hundred whole-genome resequenced samples from 8 species that diverged from 1.3 to 4.8 million years ago, the authors aim at identifying the key factors involved in the genomic differentiation between species. They carried out a wide range of robust statistical tests aiming at characterizing the genomic differentiation along the genome of these species pairs. They highlight in particular the role of linked selection and gene flow in shaping the divergence along the genomes of species pairs. They also confirm the significance of introgression among species with a net divergence larger than the upper boundaries of the grey zone of speciation previously documented in animals (da from 0.005 to 0.02, Roux et al. 2016). Because these findings pave the way to research about the genomic mechanisms associated with speciation in species with allopatric and parapatric distributions, I warmingly recommend this article. References Roux C, Fraïsse C, Romiguier J, Anciaux Y, Galtier N, Bierne N (2016) Shedding Light on the Grey Zone of Speciation along a Continuum of Genomic Divergence. PLOS Biology, 14, e2000234. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2000234 Shang H, Rendón-Anaya M, Paun O, Field DL, Hess J, Vogl C, Liu J, Ingvarsson PK, Lexer C, Leroy T (2023) Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient. bioRxiv, 2021.08.26.457771, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.26.457771 | Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient | Huiying Shang, Martha Rendón-Anaya, Ovidiu Paun, View David L Field, Jaqueline Hess, Claus Vogl, Jianquan Liu, Pär K. Ingvarsson, Christian Lexer, Thibault Leroy | <p style="text-align: justify;">Speciation, the continuous process by which new species form, is often investigated by looking at the variation of nucleotide diversity and differentiation across the genome (hereafter genomic landscapes). A key cha... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Violaine Llaurens | 2021-09-06 14:12:27 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer