Latest recommendations

| Id | Title▲ | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

12 Jun 2018

Transgenerational cues about local mate competition affect offspring sex ratios in the spider mite Tetranychus urticaeAlison B. Duncan, Cassandra Marinosci, Céline Devaux, Sophie Lefèvre, Sara Magalhães, Joanne Griffin, Adeline Valente, Ophélie Ronce, Isabelle Olivieri https://doi.org/10.1101/240127Maternal effects in sex-ratio adjustmentRecommended by Dries Bonte based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersOptimal sex ratios have been topic of extensive studies so far. Fisherian 1:1 proportions of males and females are known to be optimal in most (diploid) organisms, but many deviations from this golden rule are observed. These deviations not only attract a lot of attention from evolutionary biologists but also from population ecologists as they eventually determine long-term population growth. Because sex ratios are tightly linked to fitness, they can be under strong selection or plastic in response to changing demographic conditions. Hamilton [1] pointed out that an equality of the sex ratio breaks down when there is local competition for mates. Competition for mates can be considered as a special case of local resource competition. In short, this theory predicts females to adjust their offspring sex ratio conditional on cues indicating the level of local mate competition that their sons will experience. When cues indicate high levels of LMC mothers should invest more resources in the production of daughters to maximise their fitness, while offspring sex ratios should be closer to 50:50 when cues indicate low levels of LMC. References [1] Hamilton, W. D. (1967). Extraordinary Sex Ratios. Science, 156(3774), 477–488. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3774.477 | Transgenerational cues about local mate competition affect offspring sex ratios in the spider mite Tetranychus urticae | Alison B. Duncan, Cassandra Marinosci, Céline Devaux, Sophie Lefèvre, Sara Magalhães, Joanne Griffin, Adeline Valente, Ophélie Ronce, Isabelle Olivieri | <p style="text-align: justify;">In structured populations, competition between closely related males for mates, termed Local Mate Competition (LMC), is expected to select for female-biased offspring sex ratios. However, the cues underlying sex all... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Dries Bonte | 2017-12-29 16:10:32 | View | |

22 Jul 2019

Transgenerational plasticity of inducible defenses: combined effects of grand-parental, parental and current environmentsJuliette Tariel; Sandrine Plénet; Emilien Luquet https://doi.org/10.1101/589945Transgenerational plasticity through three generationsRecommended by Troy Day based on reviews by Stewart Plaistow and 1 anonymous reviewerOrganisms very often display phenotypic plasticity, whereby the expression of trait (or suite of traits) changes in a consistent way as a function of some environmental variable. Sometimes this plastic response remains labile and so the trait continues to respond to the environment throughout an organism’s life, but there are also many examples in which environmental conditions during a critical developmental window irreversibly set the stage for how a trait will be expressed later in life. References [1] West-Eberhard, M. J. (2003). Developmental plasticity and evolution. Oxford University Press. | Transgenerational plasticity of inducible defenses: combined effects of grand-parental, parental and current environments | Juliette Tariel; Sandrine Plénet; Emilien Luquet | <p>While an increasing number of studies highlights that parental environment shapes offspring phenotype (transgenerational plasticity TGP), TGP beyond the parental generation has received less attention. Studies suggest that TGP impacts populatio... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Non Genetic Inheritance, Phenotypic Plasticity | Troy Day | 2019-03-29 09:31:53 | View | |

05 Aug 2020

Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognitaDjampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.30.069948DNA transposons drive genome evolution of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognitaRecommended by Ines Alvarez based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers

Duplications, mutations and recombination may be considered the main sources of genomic variation and evolution. In addition, sexual recombination is essential in purging deleterious mutations and allowing advantageous allelic combinations to occur (Glémin et al. 2019). However, in parthenogenetic asexual organisms, variation cannot be explained by sexual recombination, and other mechanisms must account for it. Although it is known that transposable elements (TE) may influence on genome structure and gene expression patterns, their role as a primary source of genomic variation and rapid adaptability has received less attention. An important role of TE on adaptive genome evolution has been documented for fungal phytopathogens (Faino et al. 2016), suggesting that TE activity might explain the evolutionary dynamics of this type of organisms. References [1] Bessereau J-L. 2006. Transposons in C. elegans. WormBook. 10.1895/wormbook.1.70.1 | Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita | Djampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin | <p>Despite reproducing without sexual recombination, the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita is adaptive and versatile. Indeed, this species displays a global distribution, is able to parasitize a large range of plants and can overcome plant ... | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Ines Alvarez | 2020-05-04 11:43:14 | View | ||

04 Nov 2020

Treating symptomatic infections and the co-evolution of virulence and drug resistanceSamuel Alizon https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.29.970905More intense symptoms, more treatment, more drug-resistance: coevolution of virulence and drug-resistanceRecommended by Ludek Berec based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersMathematical models play an essential role in current evolutionary biology, and evolutionary epidemiology is not an exception [1]. While the issues of virulence evolution and drug-resistance evolution resonate in the literature for quite some time [2, 3], the study by Alizon [4] is one of a few that consider co-evolution of both these traits [5]. The idea behind this study is the following: treating individuals with more severe symptoms at a higher rate (which appears to be quite natural) leads to an appearance of virulent drug-resistant strains, via treatment failure. The author then shows that virulence in drug-resistant strains may face different selective pressures than in drug-sensitive strains and hence proceed at different rates. Hence, treatment itself modulates evolution of virulence. As one of the reviewers emphasizes, the present manuscript offers a mathematical view on why the resistant and more virulent strains can be selected in epidemics. Also, we both find important that the author highlights that the topic and results of this study can be attributed to public health policies and development of optimal treatment protocols [6]. References [1] Gandon S, Day T, Metcalf JE, Grenfell BT (2016) Forecasting epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of infectious diseases. Trends Ecol Evol 31: 776-788. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.07.010 | Treating symptomatic infections and the co-evolution of virulence and drug resistance | Samuel Alizon | <p>Antimicrobial therapeutic treatments are by definition applied after the onset of symptoms, which tend to correlate with infection severity. Using mathematical epidemiology models, I explore how this link affects the coevolutionary dynamics bet... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Ludek Berec | 2020-03-04 10:18:39 | View | |

05 Oct 2017

Using Connectivity To Identify Climatic Drivers Of Local AdaptationStewart L. Macdonald, John Llewelyn, Ben Phillips 10.1101/145169A new approach to identifying drivers of local adaptationRecommended by Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer based on reviews by Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer and Thomas LenormandLocal adaptation, the higher fitness a population achieves in its local “home” environment relative to other environments is a crucial phase in the divergence of populations, and as such both generates and maintains diversity. Local adaptation is enhanced by selection and genetic variation in the relevant traits, and decreased by gene flow and genetic drift. Demonstrating local adaptation is laborious, and is typically done with a reciprocal transplant design [1], documenting repeated geographic clines [e.g. 2, 3] also provides strong evidence of local adaptation. Even when well documented, it is often unknown which aspects of the environment impose selection. Indeed, differences in environment between different sites that are measured during studies of local adaptation explain little of the variance in the degree of local adaptation [4]. This poses a problem to population management. Given climate change and habitat destruction, understanding the environmental drivers of local adaptation can be crucially important to conducting successful assisted migration or targeted gene flow. In this manuscript, Macdonald et al. [5] propose a means of identifying which aspects of the environment select for local adaptation without conducting a reciprocal transplant experiment. The idea is that the strength of relationships between traits and environmental variables that are due to plastic responses to the environment will not be influenced by gene flow, but the strength of trait-environment relationships that are due to local adaptation should decrease with gene flow. This then can be used to reduce the somewhat arbitrary list of environmental variables on which data are available down to a targeted list more likely to drive local adaptation in specific traits. To perform such an analysis requires three things: 1) measurements of traits of interest in a species across locations, 2) an estimate of gene flow between locations, which can be replaced with a biologically meaningful estimate of how well connected those locations are from the point of view of the study species, and 3) data on climate and other environmental variables from across a species’ range, many of which are available on line. Macdonald et al. [5] demonstrate their approach using a skink (Lampropholis coggeri). They collected morphological and physiological data on individuals from multiple populations. They estimated connectivity among those locations using information on habitat suitability and dispersal potential [6], and gleaned climatic data from available databases and the literature. They find that two physiological traits, the critical minimum and maximum temperatures, show the strongest signs of local adaptation, specifically local adaptation to annual mean precipitation, precipitation of the driest quarter, and minimum annual temperature. These are then aspects of skink phenotype and skink habitats that could be explored further, or could be used to provide background information if migration efforts, for example for genetic rescue [7] were initiated. The approach laid out has the potential to spark a novel genre of research on local adaptation. It its simplest form, knowing that local adaptation is eroded by gene flow, it is intuitive to consider that if connectivity reduces the strength of the relationship between an environmental variable and a trait, that the trait might be involved in local adaptation. The approach is less intuitive than that, however – it relies not connectivity per-se, but the interaction between connectivity and different environmental variables and how that interaction alters trait-environment relationships. The authors lay out a number of useful caveats and potential areas that could use further development. It will be interesting to see how the community of evolutionary biologists responds. References [1] Blanquart F, Kaltz O, Nuismer SL and Gandon S. 2013. A practical guide to measuring local adaptation. Ecology Letters, 16: 1195-1205. doi: 10.1111/ele.12150 [2] Huey RB, Gilchrist GW, Carlson ML, Berrigan D and Serra L. 2000. Rapid evolution of a geographic cline in size in an introduced fly. Science, 287: 308-309. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.308 [3] Milesi P, Lenormand T, Lagneau C, Weill M and Labbé P. 2016. Relating fitness to long-term environmental variations in natura. Molecular Ecology, 25: 5483-5499. doi: 10.1111/mec.13855 [4] Hereford, J. 2009. A quantitative survey of local adaptation and fitness trade-offs. The American Naturalist 173: 579-588. doi: 10.1086/597611 [5] Macdonald SL, Llewelyn J and Phillips BL. 2017. Using connectivity to identify climatic drivers of local adaptation. bioRxiv, ver. 4 of October 4, 2017. doi: 10.1101/145169 [6] Macdonald SL, Llewelyn J, Moritz C and Phillips BL. 2017. Peripheral isolates as sources of adaptive diversity under climate change. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 5:88. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2017.00088 [7] Whiteley AR, Fitzpatrick SW, Funk WC and Tallmon DA. 2015. Genetic rescue to the rescue. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30: 42-49. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.10.009 | Using Connectivity To Identify Climatic Drivers Of Local Adaptation | Stewart L. Macdonald, John Llewelyn, Ben Phillips | Despite being able to conclusively demonstrate local adaptation, we are still often unable to objectively determine the climatic drivers of local adaptation. Given the rapid rate of global change, understanding the climatic drivers of local adapta... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications | Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer | Thomas Lenormand | 2017-06-06 13:06:54 | View |

06 Jul 2018

Variation in competitive ability with mating system, ploidy and range expansion in four Capsella speciesXuyue Yang, Martin Lascoux and Sylvain Glémin https://doi.org/10.1101/214866When ecology meets genetics: Towards an integrated understanding of mating system transitions and diversityRecommended by Sylvain Billiard and Henrique Teotonio based on reviews by Yaniv Brandvain, Henrique Teotonio and 1 anonymous reviewerIn the 19th century, C. Darwin and F. Delpino engaged in a debate about the success of species with different reproduction modes, with the later favouring the idea that monoecious plants capable of autonomous selfing could spread more easily than dioecious plants (or self-incompatible hermaphroditic plants) if cross-pollination opportunities were limited [1]. Since then, debate has never faded about how natural selection is responsible for transitions to selfing and can explain the diversity and distribution of reproduction modes we observe in the natural world [2, 3]. References [1] Darwin, C. R. (1876). The effects of cross and self fertilization in the vegetable kingdom. London: Murray.

[2] Stebbins, G. L. (1957). Self fertilization and population variability in the higher plants. The American Naturalist, 91, 337-354. doi: 10.1086/281999 | Variation in competitive ability with mating system, ploidy and range expansion in four Capsella species | Xuyue Yang, Martin Lascoux and Sylvain Glémin | <p>Self-fertilization is often associated with ecological traits corresponding to the ruderal strategy in Grime’s Competitive-Stress-tolerant-Ruderal (CSR) classification of ecological strategies. Consequently, selfers are expected to be less comp... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Sylvain Billiard | 2017-11-06 19:54:52 | View | |

22 May 2023

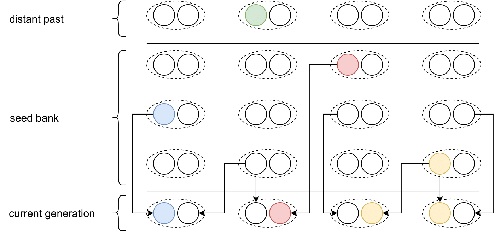

Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweepsKevin Korfmann, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.26.489499New insights into the dynamics of selective sweeps in seed-banked speciesRecommended by Renaud Vitalis based on reviews by Guillaume Achaz, Jere Koskela, William Shoemaker and Simon Boitard based on reviews by Guillaume Achaz, Jere Koskela, William Shoemaker and Simon Boitard

Many organisms across the Tree of life have the ability to produce seeds, eggs, cysts, or spores, that can remain dormant for several generations before hatching. This widespread adaptive trait in bacteria, fungi, plants and animals, has a significant impact on the ecology, population dynamics and population genetics of species that express it (Evans and Dennehy 2005). In population genetics, and despite the recognition of its evolutionary importance in many empirical studies, few theoretical models have been developed to characterize the evolutionary consequences of this trait on the level and distribution of neutral genetic diversity (see, e.g., Kaj et al. 2001; Vitalis et al. 2004), and also on the dynamics of selected alleles (see, e.g., Živković and Tellier 2018). However, due to the complexity of the interactions between evolutionary forces in the presence of dormancy, the fate of selected mutations in their genomic environment is not yet fully understood, even from the most recently developed models. In a comprehensive article, Korfmann et al. (2023) aim to fill this gap by investigating the effect of germ banking on the probability of (and time to) fixation of beneficial mutations, as well as on the shape of the selective sweep in their vicinity. To this end, Korfmann et al. (2023) developed and released their own forward-in-time simulator of genome-wide data, including neutral and selected polymorphisms, that makes use of Kelleher et al.’s (2018) tree sequence toolkit to keep track of gene genealogies. The originality of Korfmann et al.’s (2023) study is to provide new quantitative results for the effect of dormancy on the time to fixation of positively selected mutations, the shape of the genomic landscape in the vicinity of these mutations, and the temporal dynamics of selective sweeps. Their major finding is the prediction that germ banking creates narrower signatures of sweeps around positively selected sites, which are detectable for increased periods of time (as compared to a standard Wright-Fisher population). The availability of Korfmann et al.’s (2023) code will allow a wider range of parameter values to be explored, to extend their results to the particularities of the biology of many species. However, as they chose to extend the haploid coalescent model of Kaj et al. (2001), further development is needed to confirm the robustness of their results with a more realistic diploid model of seed dormancy. REFERENCES Evans, M. E. K., and J. J. Dennehy (2005) Germ banking: bet-hedging and variable release from egg and seed dormancy. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 80(4): 431-451. https://doi.org/10.1086/498282 Kaj, I., S. Krone, and M. Lascoux (2001) Coalescent theory for seed bank models. Journal of Applied Probability, 38(2): 285-300. https://doi.org/10.1239/jap/996986745 Kelleher, J., K. R. Thornton, J. Ashander, and P. L. Ralph (2018) Efficient pedigree recording for fast population genetics simulation. PLoS Computational Biology, 14(11): e1006581. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006581 Korfmann, K., D. Abu Awad, and A. Tellier (2023) Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweeps. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.26.489499 Vitalis, R., S. Glémin, and I. Olivieri (2004) When genes go to sleep: the population genetic consequences of seed dormancy and monocarpic perenniality. American Naturalist, 163(2): 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1086/381041 Živković, D., and A. Tellier (2018). All but sleeping? Consequences of soil seed banks on neutral and selective diversity in plant species. Mathematical Modelling in Plant Biology, 195-212. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99070-5_10 | Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweeps | Kevin Korfmann, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Seed banking (or dormancy) is a widespread bet-hedging strategy, generating a form of population overlap, which decreases the magnitude of genetic drift. The methodological complexity of integrating this trait impli... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics | Renaud Vitalis | 2022-05-23 13:01:57 | View | |

03 May 2020

When does gene flow facilitate evolutionary rescue?Matteo Tomasini, Stephan Peischl https://doi.org/10.1101/622142Reconciling the upsides and downsides of migration for evolutionary rescueRecommended by Claudia Bank based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe evolutionary response of populations to changing or novel environments is a topic that unites the interests of evolutionary biologists, ecologists, and biomedical researchers [1]. A prominent phenomenon in this research area is evolutionary rescue, whereby a population that is otherwise doomed to extinction survives due to the spread of new or pre-existing mutations that are beneficial in the new environment. Scenarios of evolutionary rescue require a specific set of parameters: the absolute growth rate has to be negative before the rescue mechanism spreads, upon which the growth rate becomes positive. However, potential examples of its relevance exist (e.g., [2]). From a theoretical point of view, the technical challenge but also the beauty of evolutionary rescue models is that they combine the study of population dynamics (i.e., changes in the size of populations) and population genetics (i.e., changes in the frequencies in the population). Together, the potential relevance of evolutionary rescue in nature and the models' theoretical appeal has resulted in a suite of modeling studies on the subject in recent years. References [1] Bell, G. (2017). Evolutionary Rescue. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 48(1), 605-627. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-023011 | When does gene flow facilitate evolutionary rescue? | Matteo Tomasini, Stephan Peischl | <p>Experimental and theoretical studies have highlighted the impact of gene flow on the probability of evolutionary rescue in structured habitats. Mathematical modelling and simulations of evolutionary rescue in spatially or otherwise structured p... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Claudia Bank | 2019-05-22 11:12:13 | View | |

06 May 2019

When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexualsFlorian Lavigne, Guillaume Martin, Yoann Anciaux, Julien Papaïx, Lionel Roques https://doi.org/10.1101/433235Fisher to the rescueRecommended by François Blanquart and Florence Débarre based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe ability of a population to adapt to a new niche is an important phenomenon in evolutionary biology. The colonisation of a new volcanic island by plant species; the colonisation of a host treated by antibiotics by a-resistant strain; the Ebola virus transmitting from bats to humans and spreading epidemically in Western Africa, are all examples of a population invading a new niche, adapting and eventually establishing in this new environment. Adaptation to a new niche can be studied using source-sink models. In the original environment —the “source”—, the population enjoys a positive growth-rate and is self-sustaining, while in the new environment —the “sink”— the population has a negative growth rate and is able to sustain only by the continuous influx of migrants from the source. Understanding the dynamics of adaptation to the sink environment is challenging from a theoretical standpoint, because it requires modelling the demography of the sink as well as the transient dynamics of adaptation. Moreover, local selection in the sink and immigration from the source create distributions of genotypes that complicate the use of many common mathematical approaches. In their paper, Lavigne et al. [1], develop a new deterministic model of adaptation to a harsh sink environment in an asexual species. The fitness of an individual is maximal when a number of phenotypes are tuned to an optimal value, and declines monotonously as phenotypes are further away from this optimum. This model —called Fisher’s Geometric Model— generates a GxE interaction for fitness because the phenotypic optimum in the sink environment is distinct from that in the source environment [2]. The authors circumvent mathematical difficulties by developing an original approach based on tracking the deterministic dynamics of the cumulant generating function of the fitness distribution in the sink. They derive a number of important results on the dynamics of adaptation to the sink:

In conclusion, this theoretical work presents a method based on Fisher’s Geometric Model and the use of cumulant generating functions to resolve some aspects of adaptation to a sink environment. It generates a number of theoretical predictions for the adaptive colonisation of a sink by an asexual species with some standing genetic variation. It will be a fascinating task to examine whether these predictions hold in experimental evolution systems: will we observe the four phases of the dynamics of mean fitness in the sink environment? Will the rate of adaptation indeed be independent of the immigration rate? Is there an optimal rate of mutation for adaptation to the sink? Such critical tests of the theory will greatly improve our understanding of adaptation to novel environments. References [1] Lavigne, F., Martin, G., Anciaux, Y., Papaïx, J., and Roques, L. (2019). When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexuals. bioRxiv, 433235, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/433235 | When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexuals | Florian Lavigne, Guillaume Martin, Yoann Anciaux, Julien Papaïx, Lionel Roques | <p>The successful establishment of a population into a new empty habitat outside of its initial niche is a phenomenon akin to evolutionary rescue in the presence of immigration. It underlies a wide range of processes, such as biological invasions ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology | François Blanquart | 2018-10-03 20:59:16 | View | |

13 Jan 2019

Why cooperation is not running awayFélix Geoffroy, Nicolas Baumard, Jean-Baptiste André https://doi.org/10.1101/316117A nice twist on partner choice theoryRecommended by Erol Akcay based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersIn this paper, Geoffroy et al. [1] deal with partner choice as a mechanism of maintaining cooperation, and argues that rather than being unequivocally a force towards improved payoffs to everyone through cooperation, partner choice can lead to “over-cooperation” where individuals can evolve to invest so much in cooperation that the costs of cooperating partially or fully negate the benefits from it. This happens when partner choice is consequential and effective, i.e., when interactions are long (so each decision to accept or reject a partner is a bigger stake) and when meeting new partners is frequent when unpaired (so that when one leaves an interaction one can find a new partner quickly). Geoffroy et al. [1] show that this tendency to select for overcooperation under such regimes can be counteracted if individuals base their acceptance-rejection of partners not just on the partner cooperativeness, but also on their own. By using tools from matching theory in economics, they show that plastic partner choice generates positive assortment between cooperativeness of the partners, and in the extreme case of perfectly assortative pairings, makes the pair the unit of selection, which selects for maximum total payoff. References [1] Geoffroy, F., Baumard, N., & Andre, J.-B. (2019). Why cooperation is not running away. bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/316117 | Why cooperation is not running away | Félix Geoffroy, Nicolas Baumard, Jean-Baptiste André | <p>A growing number of experimental and theoretical studies show the importance of partner choice as a mechanism to promote the evolution of cooperation, especially in humans. In this paper, we focus on the question of the precise quantitative lev... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Theory | Erol Akcay | 2018-05-15 10:32:51 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer