Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▲ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

18 Nov 2020

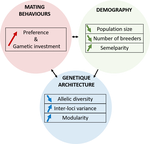

A demogenetic agent based model for the evolution of traits and genome architecture under sexual selectionLouise Chevalier, François de Coligny, Jacques Labonne https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.01.014514Sexual selection goes dynamicRecommended by Michael D Greenfield based on reviews by Frédéric Guillaume and 1 anonymous reviewer150 years after Darwin published ‘Descent of man and selection in relation to sex’ (Darwin, 1871), the evolutionary mechanism that he laid out in his treatise continues to fascinate us. Sexual selection is responsible for some of the most spectacular traits among animals, and plants, and it appeals to our interest in all things reproductive and sexual (Bell, 1982). In addition, sexual selection poses some of the more intractable problems in evolutionary biology: Its realm encompasses traits that are subject to markedly different selection pressures, particularly when distinct, yet associated, traits tend to be associated with males, e.g. courtship signals, and with females, e.g. preferences (cf. Ah-King & Ahnesjo, 2013). While separate, such traits cannot evolve independently of each other (Arnqvist & Rowe, 2005), and complex feedback loops and correlations between them are predicted (Greenfield et al., 2014). Traditionally, sexual selection has been modelled under simplifying assumptions, and quantitative genetic approaches that avoided evolutionary dynamics have prevailed. New computing methods may be able to free the field from these constraints, and a trio of theoreticians (Chevalier, De Coligny & Labonne 2020) describe here a novel application of a ‘demo-genetic agent (or individual) based model’, a mouthful hereafter termed DG-ABM, for arriving at a holistic picture of the sexual selection trajectory. The application is built on the premise that traits, e.g. courtship, preference, gamete investment, competitiveness for mates, can influence the genetic architecture, e.g. correlations, of those traits. In turn, the genetic architecture can influence the expression and evolvability of the traits. Much of this influence occurs via demographic features, i.e. social environment, generated by behavioral interactions during sexual advertisement, courtship, mate guarding, parental care, post-mating dispersal, etc. References Ah-King, M. and Ahnesjo, I. 2013. The ‘sex role’ concept: An overview and evaluation Evolutionary Biology, 40, 461-470. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11692-013-9226-7 | A demogenetic agent based model for the evolution of traits and genome architecture under sexual selection | Louise Chevalier, François de Coligny, Jacques Labonne | <p>Sexual selection has long been known to favor the evolution of mating behaviors such as mate preference and competitiveness, and to affect their genetic architecture, for instance by favoring genetic correlation between some traits. Reciprocall... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics, Sexual Selection | Michael D Greenfield | 2020-04-02 14:44:25 | View | |

16 Mar 2017

POSTPRINT

Correlated paternity measures mate monopolization and scales with the magnitude of sexual selectionDorken, ME and Perry LE 10.1111/jeb.13013Measurement of sexual selection in plants made easierRecommended by Emmanuelle Porcher and Mathilde DufaySexual selection occurs in flowering plants too. However it tends to be understudied in comparison to animal sexual selection, in part because the minuscule size and long dispersal distances of the individuals producing male gametes (pollen grains) seriously complicate the estimation of male siring success and thereby the measurement of sexual selection. Dorken and Perry [1] introduce a novel and clever approach to estimate sexual selection in plants, which bypasses the need for a direct quantification of absolute male mating success. This approach builds on the fact that the strength of sexual selection is directly related to the ability of individuals to monopolize mates [2]. In plants, mate monopolization can be assessed by examining the proportion of seeds produced by a given plant that are full-sibs, i.e. that share the same father. A nice feature of this proportion of full-sib seeds per maternal parent is it equals the coefficient of correlated paternity of Ritland [3], which can be readily obtained from the hundreds of plant mating system studies using genetic markers. A less desirable feature of the proportion of full sibs per maternal plant is that it is inversely related to population size, an effect that should be corrected for. The resulting index of mate monopolization is a simple product: (coefficient of correlated paternity)x(population size – 1). The authors test whether their index of mate monopolization is a good correlate of sexual selection, measured more traditionally as the selection differential on a trait influencing mating success, using a combination of theoretical and experimental approaches. Both approaches confirm that the two quantities are positively correlated, which suggests that the index of mate monopolization could be a convenient way to estimate the relative strength of sexual selection in flowering plants. These results call for further investigation, e.g. to verify that the effect of population size is well controlled for, or to assess the effects of non-random mating and inbreeding depression; however, this work paves the way for an expansion of sexual selection studies in flowering plants. References [1] Dorken ME and Perry LE. 2017. Correlated paternity measures mate monopolization and scales with the magnitude of sexual selection. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 30: 377-387 doi: 10.1111/jeb.13013 [2] Klug H, Heuschele J, Jennions M and Kokko H. 2010. The mismeasurement of sexual selection. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 23:447-462. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01921.x [3] Ritland K. 1989. Correlated matings in the partial selfer Mimulus guttatus. Evolution 43:848-859. doi: 10.2307/2409312 | Correlated paternity measures mate monopolization and scales with the magnitude of sexual selection | Dorken, ME and Perry LE | Indirect measures of sexual selection have been criticized because they can overestimate the magnitude of selection. In particular, they do not account for the degree to which mating opportunities can be monopolized by individuals of the sex that ... |  | Sexual Selection | Emmanuelle Porcher | 2017-03-13 23:22:26 | View | |

01 Sep 2021

Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail speciesJarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242Determinants of population genetic structure in co-occurring freshwater snailsRecommended by Trine Bilde and Matteo Fumagalli and Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Genetic diversity is a key aspect of biodiversity and has important implications for evolutionary potential and thereby the persistence of species. Improving our understanding of the factors that drive genetic structure within and between populations is, therefore, a long-standing goal in evolutionary biology. However, this is a major challenge, because of the complex interplay between genetic drift, migration, and extinction/colonization dynamics on the one hand, and the biology and ecology of species on the other hand (Romiguier et al. 2014, Ellegren and Galtier 2016, Charlesworth 2003). Jarne et al. (2021) studied whether environmental and demographic factors affect the population genetic structure of four species of hermaphroditic freshwater snails in a similar way, using comparative analyses of neutral genetic microsatellite markers. Specifically, they investigated microsatellite variability of Hygrophila in almost 280 sites in Guadeloupe, Lesser Antilles, as part of a long-term survey experiment (Lamy et al. 2013). They then modelled the influence of the mating system, local environmental characteristics and demographic factors on population genetic diversity. Consistent with theoretical predictions (Charlesworth 2003), they detected higher genetic variation in two outcrossing species than in two selfing species, emphasizing the importance of the mating system in maintaining genetic diversity. The study further identified an important role of site connectivity, through its influences on effective population size and extinction/colonisation events. Finally, the study detects an influence of interspecific interactions caused by an ongoing invasion by one of the studied species on genetic structure, highlighting the indirect effect of changes in community composition and demography on population genetics. Jarne et al. (2021) could address the extent to which genetic structure is determined by demographic and environmental factors in multiple species given the remarkable sampling available. Additionally, the study system is extremely suitable to address this hypothesis as species’ habitats are defined and delineated. Whilst the authors did attempt to test for across-species correlations, further investigations on this matter are required. Moreover, the effect of interactions between factors should be appropriately considered in any modelling between genetic structure and local environmental or demographic features. The findings in this study contribute to improving our understanding of factors influencing population genetic diversity, and highlights the complexity of interacting factors, therefore also emphasizing the challenges of drawing general implications, additionally hampered by the relatively limited number of species studied. Jarne et al. (2021) provide an excellent showcase of an empirical framework to test determinants of genetic structure in natural populations. As such, this study can be an example for further attempts of comparative analysis of genetic diversity. References Charlesworth, D. (2003) Effects of inbreeding on the genetic diversity of populations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358, 1051-1070. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2003.1296 Ellegren, H. and Galtier, N. (2016) Determinants of genetic diversity. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17, 422-433. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.58 Jarne, P., Lozano del Campo, A., Lamy, T., Chapuis, E., Dubart, M., Segard, A., Canard, E., Pointier, J.-P. and David, P. (2021) Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species. HAL, hal-03295242, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242 Lamy, T., Gimenez, O., Pointier, J. P., Jarne, P. and David, P. (2013). Metapopulation dynamics of species with cryptic life stages. The American Naturalist, 181, 479-491. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/669676 Romiguier, J., Gayral, P., Ballenghien, M. et al. (2014) Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature, 515, 261-263. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13685 | Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species | Jarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. | <p style="text-align: justify;">The distribution of neutral genetic variation in subdivided populations is driven by the interplay between genetic drift, migration, local extinction and colonization. The influence of environmental and demographic ... | Adaptation, Evolutionary Dynamics, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Trine Bilde | 2021-02-11 19:57:51 | View | ||

17 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Evolution of HIV virulence in response to widespread scale up of antiretroviral therapy: a modeling studyHerbeck JT, Mittler JE, Gottlieb GS, Goodreau SM, Murphy JT, Cori A, Pickles M, Fraser C 10.1093/ve/vew028Predicting HIV virulence evolution in response to widespread treatmentRecommended by Samuel Alizon and Roger Kouyos and Roger Kouyos

It is a classical result in the virulence evolution literature that treatments decreasing parasite replication within the host should select for higher replication rates, thus driving increased levels of virulence if the two are correlated. There is some evidence for this in vitro but very little in the field. HIV infections in humans offer a unique opportunity to go beyond the simple predictions that treatments should favour more virulent strains because many details of this host-parasite system are known, especially the link between set-point virus load, transmission rate and virulence. To tackle this question, Herbeck et al. [1] used a detailed individual-based model. This is original because it allows them to integrate existing knowledge from the epidemiology and evolution of HIV (e.g. recent estimates of the ‘heritability’ of set-point virus load from one infection to the next). This detailed model allows them to formulate predictions regarding the effect of different treatment policies; especially regarding the current policy switch away from treatment initiation based on CD4 counts towards universal treatment. The results show that, perhaps as expected from the theory, treatments based on the level of remaining host target cells (CD4 T cells) do not affect virulence evolution because they do not strongly affect the virulence level that maximizes HIV’s transmission potential. However, early treatments can lead to moderate increase in virulence within several years if coverage is high enough. These results seem quite robust to variation of all the parameters in realistic ranges. The great step forward in this model is the ability to obtain quantitative prediction regarding how a virus may evolve in response to public health policies. Here the main conclusion is that given our current knowledge in HIV biology, the risk of virulence evolution is perhaps more limited than expected from a direct application of virulence evolution model. Interestingly, the authors also conclude that recently observed increased in HIV virulence [2-3] cannot be explained by the impact of antiretroviral therapy alone; which raises the question about the main mechanism behind this increase. Finally, the authors make the interesting suggestion that “changing virulence is amenable to being monitored alongside transmitted drug resistance in sentinel surveillance”. References [1] Herbeck JT, Mittler JE, Gottlieb GS, Goodreau SM, Murphy JT, Cori A, Pickles M, Fraser C. 2016. Evolution of HIV virulence in response to widespread scale up of antiretroviral therapy: a modeling study. Virus Evolution 2:vew028. doi: 10.1093/ve/vew028 [2] Herbeck JT, Müller V, Maust BS, Ledergerber B, Torti C, et al. 2012. Is the virulence of HIV changing? A meta-analysis of trends in prognostic markers of HIV disease progression and transmission. AIDS 26:193-205. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834db418 [3] Pantazis N, Porter K, Costagliola D, De Luca A, Ghosn J, et al. 2014. Temporal trends in prognostic markers of HIV-1 virulence and transmissibility: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV 1:e119-26. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3018(14)00002-2 | Evolution of HIV virulence in response to widespread scale up of antiretroviral therapy: a modeling study | Herbeck JT, Mittler JE, Gottlieb GS, Goodreau SM, Murphy JT, Cori A, Pickles M, Fraser C | There are global increases in the use of HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART), guided by clinical benefits of early ART initiation and the efficacy of treatment as prevention of transmission. Separately, it has been shown theoretically and empirically... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Samuel Alizon | 2016-12-16 20:54:08 | View | |

15 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Limiting opportunities for cheating stabilizes virulence in insect parasitic nematodesShapiro-Ilan D. and B. Raymond doi:10.1111/eva.12348Application of kin theory to long-standing problem in nematode production for biocontrolRecommended by Thomas Sappington and Ruth Arabelle HufbauerMuch research effort has been extended toward developing systems for managing soil inhabiting insect pests of crops with entomopathogenic nematodes as biocontrol agents. Although small plot or laboratory experiments may suggest a particular insect pest is vulnerable to management in this way, it is often difficult to scale-up nematode production for application at the field- and farm scale to make such a tactic viable. Part of the problem is that entomopathogenic nematode strains must be propagated by serial passage in vivo, because storage by freezing decreases fitness. At the same time, serial propagation results in loss of virulence (ability to infect) over generations in the laboratory, a phenomenon called attenuation. To probe the underlying reasons for development of attenuation, as a prerequisite to designing strategies to mitigate it, Shapiro-Ilan and Raymond [1] turned to evolutionary theory of social conflict as a possible explanatory framework. Virulence of entomopathogenic nematodes depends on a combination of virulence factors, like various proteases, secreted by both the nematode and symbiotic bacteria to overcome host defenses. Attenuation is characterized in part by a reduced production of these factors. Invasion of a host involves simultaneous attack by a group of nematodes ("cooperators"), which together neutralize host defenses enough to allow individuals to successfully invade. "Cheaters" in the invading population can avoid the metabolic costs of producing virulence factors while reaping the benefits of infecting the host made vulnerable by the cooperators in the population. The authors hypothesize that an increase in frequency of cheaters may contribute to attenuation of virulence during serial propagation in the laboratory. The evolutionary dynamics of cheater frequency in a population have been explored in many contexts as part of kin selection theory. Cheaters can increase in a population by outcompeting cooperators in a host if overall relatedness within the invading population is low. Conversely, frequency of altruism, or costly cooperation, increases in a population if relatedness is high, which is enhanced by low effective dispersal. However, a population that is too isolated can suffer from inbreeding effects, and competition will occur mainly among relatives, which decreases the fitness benefits of altruism. Shapiro-Ilan and Raymond [1] tested changes in virulence and reproductive output in a serially propagated entomopathogenic nematode, Heterorhabditis floridensis. They compared lines of high or low relatedness, manipulated via multiplicity of infection (MOI) rates (where a low dose of nematodes gives high relatedness and a high dose gives low relatedness); and under global or local competition, manipulated by pooling populations emerging from all or only two host cadavers per generation, respectively. As predicted, treatments of high relatedness (low MOI) and global competition had the greatest level of reproduction, while all lines of low relatedness (high MOI) evolved decreased reproduction and decreased virulence, which led to extinction. The key finding was that lines in the high relatedness (low MOI) and low (local) competition treatment exhibited the most stable virulence through the 12 generations tested. Thus, to minimize attenuation of virulence while maintaining fitness of recently isolated entomopathogenic nematodes, the authors recommend insect hosts be inoculated with low doses of nematodes from inocula pools from as few cadavers as possible. The application of evolutionary theory, with a clever experimental design, to an important problem in pest management makes this paper particularly noteworthy. Reference [1] Shapiro-Ilan D, Raymond B. 2016. Limiting opportunities for cheating stabilizes virulence in insect parasitic nematodes. Evolutionary Applications 9:462-470. doi: 10.1111/eva.12348 | Limiting opportunities for cheating stabilizes virulence in insect parasitic nematodes | Shapiro-Ilan D. and B. Raymond | Cooperative secretion of virulence factors by pathogens can lead to social conflict when cheating mutants exploit collective secretion, but do not contribute to it. If cheats outcompete cooperators within hosts, this can cause loss of virulence.... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory, Experimental Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Thomas Sappington | 2016-12-15 18:33:39 | View | |

16 Dec 2020

Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivityMaxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Marjorie Haond, Aurélie Blin, Eric Lombaert, Vincent Calcagno, Simon Fellous, Ludovic Mailleret, Thibaut Malausa, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.13.092775The push and pull between theory and data in understanding the dynamics of invasionRecommended by Ben Phillips based on reviews by Laura Naslund and 2 anonymous reviewersExciting times are afoot for those of us interested in the ecology and evolution of invasive populations. Recent years have seen evolutionary process woven firmly into our understanding of invasions (Miller et al. 2020). This integration has inspired a welter of empirical and theoretical work. We have moved from field observations and verbal models to replicate experiments and sophisticated mathematical models. Progress has been rapid, and we have seen science at its best; an intimate discussion between theory and data. References Bîrzu, G., Matin, S., Hallatschek, O., and Korolev, K. S. (2019). Genetic drift in range expansions is very sensitive to density dependence in dispersal and growth. Ecology Letters, 22(11), 1817-1827. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13364 | Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivity | Maxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Marjorie Haond, Aurélie Blin, Eric Lombaert, Vincent Calcagno, Simon Fellous, Ludovic Mailleret, Thibaut Malausa, Elodie Vercken | <p>Range expansions are key processes shaping the distribution of species; their ecological and evolutionary dynamics have become especially relevant today, as human influence reshapes ecosystems worldwide. Many attempts to explain and predict ran... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Ben Phillips | 2020-08-04 12:51:56 | View | |

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Addicted? Reduced host resistance in populations with defensive symbiontsMartinez J, Cogni R, Cao C, Smith S, Illingworth CJR & Jiggins FM 10.1098/rspb.2016.0778Hooked on WolbachiaRecommended by Ana Rivero and Natacha KremerThis very nice paper by Martinez et al. [1] provides further evidence, if further evidence was needed, of the extent to which heritable microorganisms run the evolutionary show. Reference [1] Martinez J, Cogni R, Cao C, Smith S, Illingworth CJR & Jiggins FM. 2016. Addicted? Reduced host resistance in populations with defensive symbionts. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 283:20160778. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.0778 | Addicted? Reduced host resistance in populations with defensive symbionts | Martinez J, Cogni R, Cao C, Smith S, Illingworth CJR & Jiggins FM | Heritable symbionts that protect their hosts from pathogens have been described in a wide range of insect species. By reducing the incidence or severity of infection, these symbionts have the potential to reduce the strength of selection on genes ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Life History | Ana Rivero | 2016-12-13 20:08:37 | View | |

11 Sep 2017

POSTPRINT

Less effective selection leads to larger genomesTristan Lefébure, Claire Morvan, Florian Malard, Clémentine François, Lara Konecny-Dupré, Laurent Guéguen, Michèle Weiss-Gayet, Andaine Seguin-Orlando, Luca Ermini, Clio Der Sarkissian, N. Pierre Charrier, David Eme, Florian Mermillod-Blondin, Laurent Duret, Cristina Vieira, Ludovic Orlando and Christophe Douady 10.1101/gr.212589.116Colonisation of subterranean ecosystems leads to larger genome in waterlouse (Aselloidea)Recommended by Benoit Nabholz and Jochen B. W. WolfThe total amount of DNA utilized to store hereditary information varies immensely among eukaryotic organisms. Single copy genome sizes – disregarding differences due to ploidy - differ by more than three orders of magnitude ranging from a few million nucleotides (Mb) to hundreds of billions (Gb). With the ever-increasing availability of fully sequenced genomes we now know that most of the difference is due either to whole genome duplication or to variation in the abundance of repetitive elements. Regarding repetitive elements, the evolutionary forces underlying the large variation 'allowing' more or less elements in a genome remain largely elusive. A tentative correlation between an organism's complexity (however this may be adequately measured) and genome size, the so called C-value paradox [1], has long been dismissed. Studies testing for selection on secondary phenotypic effects associated with genome size (cell size, metabolic rates, nutrient availability) have yielded mixed results. Nonadaptive theories capitalizing on a role of deleterious insertion-deletion mutations and genetic drift as the main drivers have likewise received mixed support [2-3]. Overall, most evidence was derived from analyses across broad taxonomical scales [4-6]. Lefébure and colleagues [7] take a different approach. They confine their considerations to a homogeneous, restricted taxonomical group, isopod crustaceans of the superfamily Aselloidea. This taxonomic focus allows the authors to circumvent many of the confounding factors such as phylogenetic inertia, life history divergence and mutation rate variation that tend to trouble analyses across broad taxonomic timescales. Another important feature of the chosen system is the evolutionary independent transition of habitat use that has occurred at least 11 times. One group of species inhabits subterranean ecosystems (groundwater), another group thrives on surface water. Populations of the former live in low-energy habitats and are expected to be outnumbered by their surface dwelling relatives. Interestingly – and a precondition for the study - the groundwater species have significantly larger genomes (up to 137%). With this unique set-up, the authors are able to investigate the link between genome size and evolutionary forces related to a proxy of long-term population size by removing many of the confounding factors a priori. Upfront, we learn that the dN/dS ratio is higher in the groundwater species. This may either suggest prevalent positive selection or lower efficacy of purifying selection (relaxed constraint) in the group of species in which population sizes are expected to be low. Using a series of population genetic analyses the authors provide compelling evidence for the latter. Analyses are carefully conducted and include models for estimating the intensity and frequency of purifying and positive selection, the DoS (direction of selection) and α statistic. Next the authors also exclude the possibility that increased dN/dS of the subterranean groundwater species may be due to nonfunctionalization, which may result from the subterranean lifestyle. Overall, these analyses suggest relaxed constraint in smaller populations as the most plausible alternative to explain increased dN/dS ratios. In addition to the efficacy of selection, the authors estimate the timing of the ecological transition under the rationale that the amount of time a species may have been exposed to the subterranean habitat may reflect long term population sizes. To calibrate the 'colonization clock' they apply a neat trick based on the degree of degeneration of the opsin gene (as vision tends to get lost in these habitats). When finally testing which parameters may explain differences in genome size all factors – ecological status, selection efficiency as measured by dN/dS and colonization time - turned out to be significant predictors. Direct estimates of the short term effective population size Ne from polymorphism data, however, did not correlate with genome size. Ruling out the effect of other co-variates such as body size and growth rate the authors conclude that genome size was overall best predicted by long-term population size change upon habitat shift. In that the authors provide convincing evidence that the increase in genome size is linked to a decrease in long-term reduction of selection efficiency of subterranean species. Assuming a bias for insertion mutations over deletion mutations (which is usually the case in eukaryotes) this result is in agreement with the theory of mutational hazard [4-6]. This theory proposed by Michael Lynch postulates that the accumulation of non-functional DNA has a weak deleterious effect that can only be efficiently opposed by natural selection in species with high Ne. In conclusion, Lefébure and colleagues provide novel and welcome evidence supporting a 'neutralist' hypothesis of genome size evolution without the need to invoke an adaptive component. Methodologically, the study cautions against the common use of polymorphism-based estimates of Ne which are often obfuscated by transitory demographic change. Instead, alternative measures of selection efficacy linked to long-term population size may serve as better predictors of genome size. We hope that this study will stimulate additional work testing the link between Ne and genome size variation in other taxonomical groups [8-9]. Using genome sequences instead of the transcriptome approach applied here may concomitantly further our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying genome size change. References [1] Thomas, CA Jr. 1971. The genetic organization of chromosomes. Annual Review of Genetics 5: 237–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.05.120171.001321 [2] Ågren JA, Greiner S, Johnson MTJ, Wright SI. 2015. No evidence that sex and transposable elements drive genome size variation in evening primroses. Evolution 69: 1053–1062. doi: 10.1111/evo.12627 [3] Bast J, Schaefer I, Schwander T, Maraun M, Scheu S, Kraaijeveld K. 2016. No accumulation of transposable elements in asexual arthropods. Molecular Biology and Evolution 33: 697–706. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv261 [4] Lynch M. 2007. The Origins of Genome Architecture. Sinauer Associates. [5] Lynch M, Bobay LM, Catania F, Gout JF, Rho M. 2011. The repatterning of eukaryotic genomes by random genetic drift. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 12: 347–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082410-101412 [6] Lynch M, Conery JS. 2003. The origins of genome complexity. Science 302: 1401–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1089370 [7] Lefébure T, Morvan C, Malard F, François C, Konecny-Dupré L, Guéguen L, Weiss-Gayet M, Seguin-Orlando A, Ermini L, Der Sarkissian C, Charrier NP, Eme D, Mermillod-Blondin F, Duret L, Vieira C, Orlando L, and Douady CJ. 2017. Less effective selection leads to larger genomes. Genome Research 27: 1016-1028. doi: 10.1101/gr.212589.116 [8] Lower SS, Johnston JS, Stanger-Hall KF, Hjelmen CE, Hanrahan SJ, Korunes K, Hall D. 2017. Genome size in North American fireflies: Substantial variation likely driven by neutral processes. Genome Biolology and Evolution 9: 1499–1512. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evx097 [9] Sessegolo C, Burlet N, Haudry A. 2016. Strong phylogenetic inertia on genome size and transposable element content among 26 species of flies. Biology Letters 12: 20160407. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0407 | Less effective selection leads to larger genomes | Tristan Lefébure, Claire Morvan, Florian Malard, Clémentine François, Lara Konecny-Dupré, Laurent Guéguen, Michèle Weiss-Gayet, Andaine Seguin-Orlando, Luca Ermini, Clio Der Sarkissian, N. Pierre Charrier, David Eme, Florian Mermillod-Blondin, Lau... | The evolutionary origin of the striking genome size variations found in eukaryotes remains enigmatic. The effective size of populations, by controlling selection efficacy, is expected to be a key parameter underlying genome size evolution. However... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Benoit Nabholz | 2017-09-08 09:39:23 | View | |

02 Jan 2019

Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by EricaMichael D. Pirie, Martha Kandziora, Nicolai M. Nuerk, Nicholas C. Le Maitre, Ana Laura Mugrabi de Kuppler, Berit Gehrke, Edward G.H. Oliver, and Dirk U. Bellstedt https://doi.org/10.1101/290791The colonization history of largely isolated habitatsRecommended by Andrea S. Meseguer based on reviews by Simon Joly, Florian Boucher and 2 anonymous reviewersThe build-up of biodiversity is the result of in situ speciation and immigration, with the interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability determining the probability of an organism to establish in a new area. The relative contribution of these factors have long interested biogeographers, in particular to explain the distribution of organisms adapted to habitats that remained largely isolated, such as the colonization of oceanic islands or land waters. The focus of this study is the formation of the afrotemperate flora; patches of temperate vegetation separated by thousands of kilometers in Africa, with high levels of endemism described in the Cape region, the Drakensberg range and the high mountains of tropical east Africa [1]. The floristic affinities between these centers of endemism have frequently been explored but the origin of many afrotemperate lineages remains enigmatic [2]. References [1] Linder, H.P. 1990. On the relationship between the vegetation and floras of the Afromontane and the Cape regions of Africa. Mitteilungen aus dem Institut für Allgemeine Botanik Hamburg 23b:777–790. | Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by Erica | Michael D. Pirie, Martha Kandziora, Nicolai M. Nuerk, Nicholas C. Le Maitre, Ana Laura Mugrabi de Kuppler, Berit Gehrke, Edward G.H. Oliver, and Dirk U. Bellstedt | <p>The coincidence of long distance dispersal and biome shift is assumed to be the result of a multifaceted interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability of source and sink areas. Here, we test the influence of these factors o... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography | Andrea S. Meseguer | 2018-04-09 10:10:04 | View | |

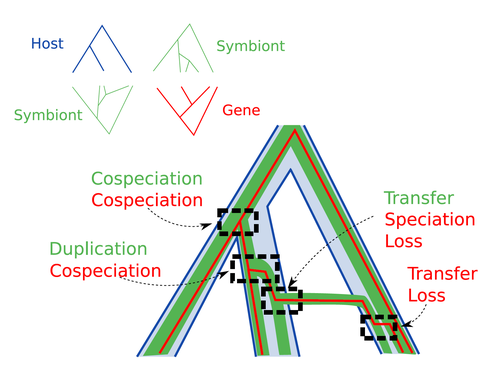

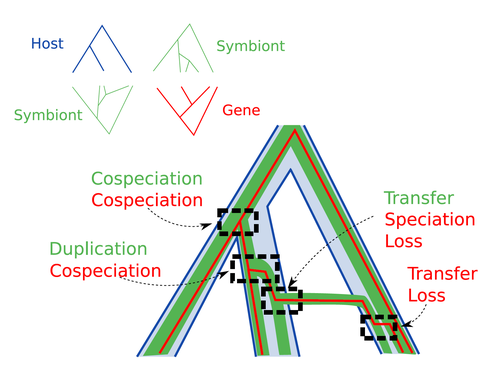

02 May 2023

Host-symbiont-gene phylogenetic reconciliationHugo Menet, Alexia Nguyen Trung, Vincent Daubin, Eric Tannier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.01.498457Reconciling molecular evolution and evolutionary ecology studies: a phylogenetic reconciliation method for gene-symbiont-host systemsRecommended by Emmanuelle Jousselin based on reviews by Vincent Berry and Catherine MatiasInteractions between species are a driving force in evolution. Many organisms host symbiotic partners that live all or part of their life in or on their host. Whether they are mutualistic or parasitic, these symbiotic associations impose strong selective pressures on both partners and affect their evolutionary trajectories. In fine, they can have a significant impact on the diversification patterns of both host and symbiont lineages, with symbiotic lineages sometimes speciating simultaneously with their hosts and/or switching from one host species to another. Long-term associations between species can also result in gene transfers between the involved organisms. Those lateral gene transfers are a source of ecological innovation but can obscure the phylogenetic signals and render the process of phylogenetic reconstructions complex (Lerat et al. 2003). Methods known as reconciliations explore similarities and differences between phylogenetic trees. They have been widely used to both compare the diversification patterns of hosts and symbionts and identify lateral gene transfers between species. Though the reconciliation approaches used in host/ symbiont and species/ gene phylogenetic studies are identical, they are always applied separately to solve either molecular evolution questions or investigate the evolution of ecological interactions. However, the two questions are often intimately linked and the current interest in multi-level systems (e.g. the holobiont concept) calls for a unique model that will take into account three-level nested organization (gene/symbiont/ host) where both symbiont and genes can transfer among hosts. Here Menet and collaborators (2023) provide such a model to produce three-level reconciliations. In order to do so, they extend the two-level reconciliation model implemented in “ALE” software (Szöllősi et al. 2013), one of the most used and proven reconciliation methods. Briefly, given a symbiont gene tree, a symbiont tree and a host tree, as in previous reconciliation models, the symbiont tree is mapped onto the host tree by mixing three types of events: Duplication, Transfer or Loss (DTL), with a possibility of the symbiont evolving temporarily outside the host phylogeny (in a “ghost” host lineage). The gene tree evolves similarly inside the symbiont tree, but horizontal transfers are constrained to symbionts co-occurring within the same host. Joint reconciliation scenarios are reconstructed and DTL event rates and likelihoods are estimated according to the model. As a nice addition, the authors propose a method to infer the symbiont phylogeny through amalgamation from gene trees and a host tree. The authors then explore the diverse possibilities offered by this method by testing it on both simulated datasets and biological datasets in order to check whether considering three nested levels is worthwhile. They convincingly show that three-level reconciliation has a better capacity to retrieve the symbiont donors and receivers of horizontal gene transfers, probably because transfers are constrained by additional elements relevant to the biological systems. Using, aphids, their obligate endosymbionts, and the symbiont genes involved in their nutritional functions, they identify horizontal gene transfers between aphid symbionts that are missed by two-level reconciliations but detected by expertise (Manzano-Marín et al. 2020). The other dataset presented here is on the human pathogen Helicobacter pylori, which history is supposed to reflect human migration. They use more than 1000 H. pylori gene families, and four populations, and use likelihood computations to compare different hypotheses on the diversification of the host. In summary, this study is a proof-of-concept of a 3-level reconciliation, where the authors manage to convey the applicability of their framework to many biological systems. Reported complexities, confirmed by reported running times, show that the method is computationally efficient. Without a doubt, the tool presented here will be very useful to evolutionary biologists who want to investigate multi-scale cophylogenies and it will move forward the study of associations between host and symbionts when symbiont genomic data are available. REFERENCES Lerat, E., Daubin, V., & Moran, N. A. (2003). From gene trees to organismal phylogeny in prokaryotes: the case of the γ-Proteobacteria. PLoS biology, 1(1), e19. Menet H, Trung AN, Daubin V, Tannier E (2023) Host-symbiont-gene phylogenetic reconciliation. bioRxiv, 2022.07.01.498457, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.01.498457 Szöllősi, G. J., Rosikiewicz, W., Boussau, B., Tannier, E., & Daubin, V. (2013). Efficient exploration of the space of reconciled gene trees. Systematic biology, 62(6), 901-912. | Host-symbiont-gene phylogenetic reconciliation | Hugo Menet, Alexia Nguyen Trung, Vincent Daubin, Eric Tannier | <p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>Motivation:</strong> Biological systems are made of entities organized at different scales e.g. macro-organisms, symbionts, genes...) which evolve in interaction.<br>These interactions range from indepe... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Emmanuelle Jousselin | 2022-08-21 18:34:27 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer