Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors▼ | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

16 Mar 2017

POSTPRINT

Correlated paternity measures mate monopolization and scales with the magnitude of sexual selectionDorken, ME and Perry LE 10.1111/jeb.13013Measurement of sexual selection in plants made easierRecommended by Emmanuelle Porcher and Mathilde DufaySexual selection occurs in flowering plants too. However it tends to be understudied in comparison to animal sexual selection, in part because the minuscule size and long dispersal distances of the individuals producing male gametes (pollen grains) seriously complicate the estimation of male siring success and thereby the measurement of sexual selection. Dorken and Perry [1] introduce a novel and clever approach to estimate sexual selection in plants, which bypasses the need for a direct quantification of absolute male mating success. This approach builds on the fact that the strength of sexual selection is directly related to the ability of individuals to monopolize mates [2]. In plants, mate monopolization can be assessed by examining the proportion of seeds produced by a given plant that are full-sibs, i.e. that share the same father. A nice feature of this proportion of full-sib seeds per maternal parent is it equals the coefficient of correlated paternity of Ritland [3], which can be readily obtained from the hundreds of plant mating system studies using genetic markers. A less desirable feature of the proportion of full sibs per maternal plant is that it is inversely related to population size, an effect that should be corrected for. The resulting index of mate monopolization is a simple product: (coefficient of correlated paternity)x(population size – 1). The authors test whether their index of mate monopolization is a good correlate of sexual selection, measured more traditionally as the selection differential on a trait influencing mating success, using a combination of theoretical and experimental approaches. Both approaches confirm that the two quantities are positively correlated, which suggests that the index of mate monopolization could be a convenient way to estimate the relative strength of sexual selection in flowering plants. These results call for further investigation, e.g. to verify that the effect of population size is well controlled for, or to assess the effects of non-random mating and inbreeding depression; however, this work paves the way for an expansion of sexual selection studies in flowering plants. References [1] Dorken ME and Perry LE. 2017. Correlated paternity measures mate monopolization and scales with the magnitude of sexual selection. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 30: 377-387 doi: 10.1111/jeb.13013 [2] Klug H, Heuschele J, Jennions M and Kokko H. 2010. The mismeasurement of sexual selection. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 23:447-462. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01921.x [3] Ritland K. 1989. Correlated matings in the partial selfer Mimulus guttatus. Evolution 43:848-859. doi: 10.2307/2409312 | Correlated paternity measures mate monopolization and scales with the magnitude of sexual selection | Dorken, ME and Perry LE | Indirect measures of sexual selection have been criticized because they can overestimate the magnitude of selection. In particular, they do not account for the degree to which mating opportunities can be monopolized by individuals of the sex that ... |  | Sexual Selection | Emmanuelle Porcher | 2017-03-13 23:22:26 | View | |

05 Aug 2020

Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognitaDjampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.30.069948DNA transposons drive genome evolution of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognitaRecommended by Ines Alvarez based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers

Duplications, mutations and recombination may be considered the main sources of genomic variation and evolution. In addition, sexual recombination is essential in purging deleterious mutations and allowing advantageous allelic combinations to occur (Glémin et al. 2019). However, in parthenogenetic asexual organisms, variation cannot be explained by sexual recombination, and other mechanisms must account for it. Although it is known that transposable elements (TE) may influence on genome structure and gene expression patterns, their role as a primary source of genomic variation and rapid adaptability has received less attention. An important role of TE on adaptive genome evolution has been documented for fungal phytopathogens (Faino et al. 2016), suggesting that TE activity might explain the evolutionary dynamics of this type of organisms. References [1] Bessereau J-L. 2006. Transposons in C. elegans. WormBook. 10.1895/wormbook.1.70.1 | Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita | Djampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin | <p>Despite reproducing without sexual recombination, the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita is adaptive and versatile. Indeed, this species displays a global distribution, is able to parasitize a large range of plants and can overcome plant ... | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Ines Alvarez | 2020-05-04 11:43:14 | View | ||

16 Dec 2022

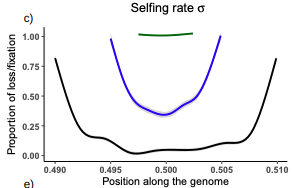

Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depressionDiala Abu Awad, Donald Waller https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.473022Pseudo-overdominance: how linkage and selection can interact and oppose to purging of deleterious mutations.Recommended by Sylvain Glémin based on reviews by Yaniv Brandvain, Lei Zhao and 1 anonymous reviewerMost mutations affecting fitness are deleterious and they have many evolutionary consequences. The dynamics and consequences of deleterious mutations are a long-standing question in evolutionary biology and a strong theoretical background has already been developed, for example, to predict the mutation load, inbreeding depression or background selection. One of the classical results is that inbreeding helps purge partially recessive deleterious mutations by exposing them to selection in homozygotes. However, this mainly results from single-locus considerations. When interactions among several, more or less linked, deleterious mutations are taken into account, peculiar dynamics can emerge. One of them, called pseudo-overdominance (POD), corresponds to the maintenance in a population of two (or more) haplotype blocks composed of several recessive deleterious mutations in repulsion that mimics overdominance. Indeed, homozygote individuals for one of the haplotype blocks expose many deleterious mutations to selection whereas they are reciprocally masked in heterozygotes, leading to higher fitness of heterozygotes compared to both homozygotes. A related process, called associative overdominance (AOD) is the effect of such deleterious alleles in repulsion on the linked neutral variation that can be increased by AOD. Although this possibility has been recognized for a long time (Otha and Kimura 1969), it has been mainly considered an anecdotal process. Recently, both theoretical (Zhao and Charlesworth 2016) and genomic analyses (Gilbert et al. 2020) have renewed interest in such a process, suggesting that it could be important in weakly recombining regions of a genome. Donald Waller (2021) - one of the co-authors of the current work - also recently proposed that POD could be quantitatively important with broad implications, and could resolve some unexplained observations such as the maintenance of inbreeding depression in highly selfing species. Yet, a proper theoretical framework analysing the effect of inbreeding on POD was lacking. In this theoretical work, Diala Abu Awad and Donald Waller (2022) addressed this question through an elegant combination of analytical predictions and intensive multilocus simulations. They determined the conditions under which POD can be maintained and how long it could resist erosion by recombination, which removes the negative association between deleterious alleles (repulsion) at the core of the mechanism. They showed that under tight linkage, POD regions can persist for a long time and generate substantial segregating load and inbreeding depression, even under inbreeding, so opposing (for a while) to the purging effect. They also showed that background selection can affect the genomic structure of POD regions by rapidly erasing weak POD regions but maintaining strong POD regions (i.e with many tightly linked deleterious alleles). These results have several implications. They can explain the maintenance of inbreeding depression despite inbreeding (as anticipated by Waller 2021), which has implications for the evolution of mating systems. If POD can hardly emerge under high selfing, it can persist from an outcrossing ancestor long after the transition towards a higher selfing rate and could explain the maintenance of mixed mating systems(which is possible with true overdominance, see Uyenoyama and Waller 1991). The results also have implications for genomic analyses, pointing to regions of low or no recombination where POD could be maintained, generating both higher diversity and heterozygosity than expected and variance in fitness. As structural variations are likely widespread in genomes with possible effects on suppressing recombination (Mérot et al. 2020), POD regions should be checked more carefully in genomic analyses (see also Gilbert et al. 2020). Overall, this work should stimulate new theoretical and empirical studies, especially to assess how quantitatively strong and widespread POD can be. It also stresses the importance of properly considering genetic linkage genome-wide, and so the role of recombination landscapes in determining patterns of diversity and fitness effects. References

Awad DA, Waller D (2022) Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depression. bioRxiv, 2021.12.16.473022, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.473022 Gilbert KJ, Pouyet F, Excoffier L, Peischl S (2020) Transition from Background Selection to Associative Overdominance Promotes Diversity in Regions of Low Recombination. Current Biology, 30, 101-107.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.11.063 Mérot C, Oomen RA, Tigano A, Wellenreuther M (2020) A Roadmap for Understanding the Evolutionary Significance of Structural Genomic Variation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35, 561–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.03.002 Ohta T, Kimura M (1969) Linkage disequilibrium at steady state determined by random genetic drift and recurrent mutation. Genetics, 63, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/63.1.229 Uyenoyama MK, Waller DM (1991) Coevolution of self-fertilization and inbreeding depression II. Symmetric overdominance in viability. Theoretical Population Biology, 40, 47–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(91)90046-I Waller DM (2021) Addressing Darwin’s dilemma: Can pseudo-overdominance explain persistent inbreeding depression and load? Evolution, 75, 779–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.14189 Zhao L, Charlesworth B (2016) Resolving the Conflict Between Associative Overdominance and Background Selection. Genetics, 203, 1315–1334. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.116.188912 | Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depression | Diala Abu Awad, Donald Waller | <p style="text-align: justify;">Classical models that ignore linkage predict that deleterious recessive mutations should purge or fix within inbred populations, yet inbred populations often retain moderate to high segregating load. True overdomina... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Sylvain Glémin | 2022-01-04 12:15:35 | View | |

20 Nov 2017

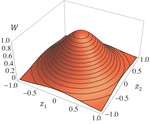

Effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance, mutation load and inbreeding depression under stabilizing selectionDiala Abu Awad and Denis Roze 10.1101/180000Understanding genetic variance, load, and inbreeding depression with selfingRecommended by Aneil F. Agrawal based on reviews by Frédéric Guillaume and 1 anonymous reviewerA classic problem in evolutionary biology is to understand the genetic variance in fitness. The simplest hypothesis is that variation exists, even in well-adapted populations, as a result of the balance between mutational input and selective elimination. This variation causes a reduction in mean fitness, known as the mutation load. Though mutation load is difficult to quantify empirically, indirect evidence of segregating genetic variation in fitness is often readily obtained by comparing the fitness of inbred and outbred offspring, i.e., by measuring inbreeding depression. Mutation-selection balance models have been studied as a means of understanding the genetic variance in fitness, mutation load, and inbreeding depression. Since their inception, such models have increased in sophistication, allowing us to ask these questions under more realistic and varied scenarios. The new theoretical work by Abu Awad and Roze [1] is a substantial step forward in understanding how arbitrary levels of self-fertilization affect variation, load and inbreeding depression under mutation-selection balance. References [1] Abu Awad D and Roze D. 2017. Effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance, mutation load and inbreeding depression under stabilizing selection. bioRxiv, 180000, ver. 4 of 17th November 2017. doi: 10.1101/180000 [2] Lande R. 1977. The influence of the mating system on the maintenance of genetic variability in polygenic characters. Genetics 86: 485–498. [3] Charlesworth D and Charlesworth B. 1987. Inbreeding depression and its evolutionary consequences. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 18: 237–268. doi: 10.1111/10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.001321 [4] Lande R and Porcher E. 2015. Maintenance of quantitative genetic variance under partial self-fertilization, with implications for the evolution of selfing. Genetics 200: 891–906. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.176693 [5] Roze D. 2015. Effects of interference between selected loci on the mutation load, inbreeding depression, and heterosis. Genetics 201: 745–757. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.178533 [6] Martin G and Lenormand T. 2006. A general multivariate extension of Fisher's geometrical model and the distribution of mutation fitness effects across species. Evolution 60: 893–907. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01169.x [7] Martin G, Elena SF and Lenormand T. 2007. Distributions of epistasis in microbes fit predictions from a fitness landscape model. Nature Genetics 39: 555–560. doi: 10.1038/ng1998 | Effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance, mutation load and inbreeding depression under stabilizing selection | Diala Abu Awad and Denis Roze | The mating system of a species is expected to have important effects on its genetic diversity. In this paper, we explore the effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance Vg, mutation load L and inbreeding depression δ under stabi... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Aneil F. Agrawal | 2017-08-26 09:29:20 | View | |

17 Feb 2020

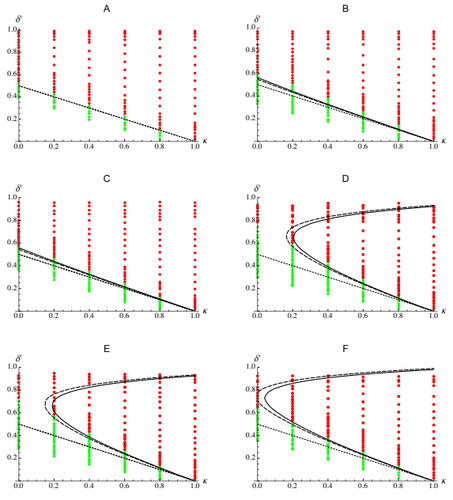

Epistasis, inbreeding depression and the evolution of self-fertilizationDiala Abu Awad and Denis Roze https://doi.org/10.1101/809814Epistasis and the evolution of selfingRecommended by Sylvain Gandon based on reviews by Nick Barton and 1 anonymous reviewerThe evolution of selfing results from a balance between multiple evolutionary forces. Selfing provides an "automatic advantage" due to the higher efficiency of selfers to transmit their genes via selfed and outcrossed offspring. Selfed offspring, however, may suffer from inbreeding depression. In principle the ultimate evolutionary outcome is easy to predict from the relative magnitude of these two evolutionary forces [1,2]. Yet, several studies explicitly taking into account the genetic architecture of inbreeding depression noted that these predictions are often too restrictive because selfing can evolve in a broader range of conditions [3,4]. References [1] Holsinger, K. E., Feldman, M. W., and Christiansen, F. B. (1984). The evolution of self-fertilization in plants: a population genetic model. The American Naturalist, 124(3), 446-453. doi: 10.1086/284287 | Epistasis, inbreeding depression and the evolution of self-fertilization | Diala Abu Awad and Denis Roze | <p>Inbreeding depression resulting from partially recessive deleterious alleles is thought to be the main genetic factor preventing self-fertilizing mutants from spreading in outcrossing hermaphroditic populations. However, deleterious alleles may... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Sylvain Gandon | 2019-10-18 09:29:41 | View | |

13 Dec 2018

A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid waspsD. Di Giovanni, D. Lepetit, M. Boulesteix, M. Ravallec, J. Varaldi https://doi.org/10.1101/342758Genetic intimacy of filamentous viruses and endoparasitoid waspsRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Alejandro Manzano Marín and 1 anonymous reviewerViruses establish intimate relationships with the cells they infect. The virocell is a novel entity, different from the original host cell and beyond the mere combination of viral and cellular genetic material. In these close encounters, viral and cellular genomes often hybridise, combine, recombine, merge and excise. Such chemical promiscuity leaves genomics scars that can be passed on to descent, in the form of deletions or duplications and, importantly, insertions and back and forth exchange of genetic material between viruses and their hosts. References [1] Di Giovanni, D., Lepetit, D., Boulesteix, M., Ravallec, M., & Varaldi, J. (2018). A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid wasps. bioRxiv, 342758, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/342758 | A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid wasps | D. Di Giovanni, D. Lepetit, M. Boulesteix, M. Ravallec, J. Varaldi | <p>To circumvent host immune response, numerous hymenopteran endo-parasitoid species produce virus-like structures in their reproductive apparatus that are injected into the host together with the eggs. These viral-like structures are absolutely n... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution | Ignacio Bravo | 2018-07-18 15:59:14 | View | |

08 Jan 2024

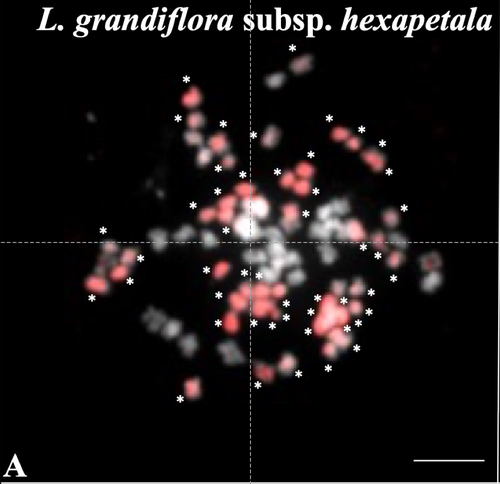

Genomic relationships among diploid and polyploid species of the genus Ludwigia L. section Jussiaea using a combination of molecular cytogenetic, morphological, and crossing investigationsD. Barloy, L. Portillo - Lemus, S. A. Krueger-Hadfield, V. Huteau, O. Coriton https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.02.522458Deciphering the genomic composition of tetraploid, hexaploid and decaploid Ludwigia L. species (section Jussiaea)Recommended by Malika AINOUCHE based on reviews by Alex BAUMEL and Karol MARHOLDPolyploidy, which results in the presence of more than two sets of homologous chromosomes represents a major feature of plant genomes that have undergone successive rounds of duplication followed by more or less rapid diploidization during their evolutionary history. Polyploid complexes containing diploid and derived polyploid taxa are excellent model systems for understanding the short-term consequences of whole genome duplication, and have been particularly well-explored in evolutionary ecology (Ramsey and Ramsey 2014, Rice et al. 2019). Many polyploids (especially when resulting from interspecific hybridization, i.e. allopolyploids) are successful invaders (te Beest et al. 2012) as a result of rapid genome dynamics, functional novelty, and trait evolution. The origin (parental legacy) and modes of formation of polyploids have a critical impact on the subsequent polyploid evolution. Thus, elucidation of the genomic composition of polyploids is fundamental to understanding trait evolution, and such knowledge is still lacking for many invasive species. Genus Ludwigia is characterized by a complex taxonomy, with an underexplored evolutionary history. Species from section Jussieae form a polyploid complex with diploids, tetraploids, hexaploids, and decaploids that are notorious invaders in freshwater and riparian ecosystems (Thouvenot et al.2013). Molecular phylogeny of the genus based on nuclear and chloroplast sequences (Liu et al. 2027) suggested some relationships between diploid and polyploid species, without fully resolving the question of the parentage of the polyploids. In their study, Barloy et al. (2023) have used a combination of molecular cytogenetics (Genomic In situ Hybridization), morphology and experimental crosses to elucidate the genomic compositions of the polyploid species, and show that the examined polyploids are of hybrid origin (allopolyploids). The tetraploid L. stolonifera derives from the diploids L. peploides subsp. montevidensis (AA genome) and L. helminthorhiza (BB genome). The tetraploid L. ascendens also share the BB genome combined with an undetermined different genome. The hexaploid L. grandiflora subsp. grandiflora has inherited the diploid AA genome combined with additional unidentified genomes. The decaploid L. grandiflora subsp. hexapetala has inherited the tetraploid L. stolonifera and the hexaploid L. grandiflora subsp. hexapetala genomes. As the authors point out, further work is needed, including additional related diploid (e.g. other subspecies of L. peploides) or tetraploid (L. hookeri and L. peduncularis) taxa that remain to be investigated, to address the nature of the undetermined parental genomes mentioned above. The presented work (Barloy et al. 2023) provides significant knowledge of this poorly investigated group with regard to genomic information and polyploid origin, and opens perspectives for future studies. The authors also detect additional diagnostic morphological traits of interest for in-situ discrimination of the taxa when monitoring invasive populations. References Barloy D., Portillo-Lemus L., Krueger-Hadfield S.A., Huteau V., Coriton O. (2024). Genomic relationships among diploid and polyploid species of the genus Ludwigia L. section Jussiaea using a combination of molecular cytogenetic, morphological, and crossing investigations. BioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.02.522458 te Beest M., Le Roux J.J., Richardson D.M., Brysting A.K., Suda J., Kubešová M., Pyšek P. (2012). The more the better? The role of polyploidy in facilitating plant invasions. Annals of Botany, Volume 109, Issue 1 Pages 19–45, https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcr277 Ramsey J. and Ramsey T. S. (2014). Ecological studies of polyploidy in the 100 years following its discovery Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B369 1–20 https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0352 Rice, A., Šmarda, P., Novosolov, M. et al. (2019). The global biogeography of polyploid plants. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0787-9 Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiebaut G. (2013). A success story: Water primroses, aquatic plant pests. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 23:790–803 https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2387 | Genomic relationships among diploid and polyploid species of the genus *Ludwigia* L. section *Jussiaea* using a combination of molecular cytogenetic, morphological, and crossing investigations | D. Barloy, L. Portillo - Lemus, S. A. Krueger-Hadfield, V. Huteau, O. Coriton | <p>ABSTRACTThe genus Ludwigia L. sectionJussiaeais composed of a polyploid species complex with 2x, 4x, 6x and 10x ploidy levels, suggesting possible hybrid origins. The aim of the present study is to understand the genomic relationships among dip... |  | Hybridization / Introgression, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Malika AINOUCHE | 2023-01-11 13:47:18 | View | |

02 Nov 2020

Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosisDavid Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265Temperature effects on virulence evolution of wMelPop Wolbachia in Drosophila melanogasterRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Shira Houwenhuyse and 3 anonymous reviewersMonnin et al. [1] here studied how Drosophila populations are affected when exposed to a high virulent endosymbiotic wMelPop Wolbachia strain and why virulent vertically transmitting endosymbionts persist in nature. This virulent wMelPop strain has been described to be a blocker of dengue and other arboviral infections in arthropod vector species, such as Aedes aegypti. Whereas it can thus function as a mutualistic symbiont, it here acts as an antagonist along the mutualism-antagonism continuum symbionts operate. The wMelPop strain is not a natural occurring strain in Drosophila melanogaster and thus the start of this experiment can be seen as a novel host-pathogen association. Through experimental evolution of 17 generations, the authors studied how high temperature affects wMelPop Wolbachia virulence and Drosophila melanogaster survival. The authors used Drosophila strains that were selected for late reproduction, given that this should favor evolution to a lower virulence. Assumptions for this hypothesis are not given in the manuscript here, but it can indeed be assumed that energy that is assimilated to symbiont tolerance instead of reproduction may lead to reduced virulence evolution. This has equally been suggested by Reyserhove et al. [2] in a dynamics energy budget model tailored to Daphnia magna virulence evolution upon a viral infection causing White fat Cell disease, reconstructing changing environments through time. References [1] Monnin, D., Kremer, N., Michaud, C., Villa, M., Henri, H., Desouhant, E. and Vavre, F. (2020) Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis. bioRxiv, 2020.04.26.062265, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265 | Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis | David Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre | <p>Evolutionary theory predicts that vertically transmitted symbionts are selected for low virulence, as their fitness is directly correlated to that of their host. In contrast with this prediction, the Wolbachia strain wMelPop drastically reduces... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Species interactions | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-04-29 19:16:56 | View | |

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

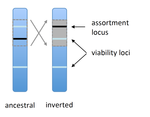

Prezygotic isolation, mating preferences, and the evolution of chromosomal inversionsDagilis AJ, Kirkpatrick M 10.1111/evo.12954The spread of chromosomal inversions as a mechanism for reinforcementRecommended by Denis Roze and Thomas Broquet

Several examples of chromosomal inversions carrying genes affecting mate choice have been reported from various organisms. Furthermore, inversions are also frequently involved in genetic isolation between populations or species. Past work has shown that inversions can spread when they capture not only some loci involved in mate choice but also loci involved in incompatibilities between hybridizing populations [1]. In this new paper [2], the authors derive analytical approximations for the selection coefficient associated with an inversion suppressing recombination between a locus involved in mate choice and one (or several) locus involved in Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities. Two mechanisms for mate choice are considered: assortative mating based on the allele present at a single locus, or a trait-preference model where one locus codes for the trait and another for the preference. The results show that such an inversion is generally favoured, the selective advantage associated with the inversion being strongest when hybridization is sufficiently frequent. Assuming pairwise epistatic interactions between loci involved in incompatibilities, selection for the inversion increases approximately linearly with the number of such loci captured by the inversion. This paper is a good read for several reasons. First, it presents the problem clearly (e.g. the introduction provides a clear and concise presentation of the issue and past work) and its crystal-clear writing facilitates the reader's understanding of theoretical approaches and results. Second, the analysis is competently done and adds to previous work by showing that very general conditions are expected to be favourable to the spread of the type of inversion considered here. And third, it provides food for thought about the role of inversions in the origin or the reinforcement of divergence between nascent species. One result of this work is that an inversion linked to pre-zygotic isolation "is favoured so long as there is viability selection against recombinant genotypes", suggesting that genetic incompatibilities must have evolved first and that inversions capturing mating preference loci may then enhance pre-existing reproductive isolation. However, the results also show that inversions are more likely to be favoured in hybridizing populations among which gene flow is still high, rather than in more strongly isolated populations. This matches the observation that inversions are more frequently observed between sympatric species than between allopatric ones. References [1] Trickett AJ, Butlin RK. 1994. Recombination Suppressors and the Evolution of New Species. Heredity 73:339-345. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1994.180 [2] Dagilis AJ, Kirkpatrick M. 2016. Prezygotic isolation, mating preferences, and the evolution of chromosomal inversions. Evolution 70: 1465–1472. doi: 10.1111/evo.12954 | Prezygotic isolation, mating preferences, and the evolution of chromosomal inversions | Dagilis AJ, Kirkpatrick M | Chromosomal inversions are frequently implicated in isolating species. Models have shown how inversions can evolve in the context of postmating isolation. Inversions are also frequently associated with mating preferences, a topic that has not been... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Denis Roze | 2016-12-13 22:11:54 | View | |

17 Jun 2022

Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process?Claire Capdevielle Dulac, Romain Benoist, Sarah Paquet, Paul-André Calatayud, Julius Obonyo, Laure Kaiser, Florence Mougel https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.13.472356The potential evolutionary importance of low-frequency flexibility in reproductive modesRecommended by Christoph Haag based on reviews by Michael Lattorff and Jens BastOccasional events of asexual reproduction in otherwise sexual taxa have been documented since a long time. Accounts range from observations of offspring development from unfertilized eggs in Drosophila to rare offspring production by isolated females in lizards and birds (e.g., Stalker 1954, Watts et al 2006, Ryder et al. 2021). Many more such cases likely await documentation, as rare events are inherently difficult to observe. These rare events of asexual reproduction are often associated with low offspring fitness (“tychoparthenogenesis”), and have mostly been discarded in the evolutionary literature as reproductive accidents without evolutionary significance. Recently, however, there has been an increased interest in the details of evolutionary transitions from sexual to asexual reproduction (e.g., Archetti 2010, Neiman et al.2014, Lenormand et al. 2016), because these details may be key to understanding why successful transitions are rare, why they occur more frequently in some groups than in others, and why certain genetic mechanisms of ploidy maintenance or ploidy restoration are more often observed than others. In this context, the hypothesis has been formulated that regular or even obligate asexual reproduction may evolve from these rare events of asexual reproduction (e.g., Schwander et al. 2010). A new study by Capdevielle Dulac et al. (2022) now investigates this question in a parasitoid wasp, highlighting also the fact that what is considered rare or occasional may differ from one system to the next. The results show “rare” parthenogenetic production of diploid daughters occurring at variable frequencies (from zero to 2 %) in different laboratory strains, as well as in a natural population. They also demonstrate parthenogenetic production of female offspring in both virgin females and mated ones, as well as no reduced fecundity of parthenogenetically produced offspring. These findings suggest that parthenogenetic production of daughters, while still being rare, may be a more regular and less deleterious reproductive feature in this species than in other cases of occasional asexuality. Indeed, haplodiploid organisms, such as this parasitoid wasp have been hypothesized to facilitate evolutionary transitions to asexuality (Neimann et al. 2014, Van Der Kooi et al. 2017). First, in haploidiploid organisms, females are diploid and develop from normal, fertilized eggs, but males are haploid as they develop parthenogenetically from unfertilized eggs. This means that, in these species, fertilization is not necessarily needed to trigger development, thus removing one of the constraints for transitions to obligate asexuality (Engelstädter 2008, Vorburger 2014). Second, spermatogenesis in males occurs by a modified meiosis that skips the first meiotic division (e.g., Ferree et al. 2019). Haploidiploid organisms may thus have a potential route for an evolutionary transition to obligate parthenogenesis that is not available to organisms: The pathways for the modified meiosis may be re-used for oogenesis, which might result in unreduced, diploid eggs. Third, the particular species studied here regularly undergoes inbreeding by brother-sister mating within their hosts. Homozygosity, including at the sex determination locus (Engelstädter 2008), is therefore expected to have less negative effects in this species compared to many other, non-inbreeding haplodipoids (see also Little et al. 2017). This particular species may therefore be less affected by loss of heterozygosity, which occurs in a fashion similar to self-fertilization under many forms of non-clonal parthenogenesis. Indeed, the study also addresses the mechanisms underlying parthenogenesis in the species. Surprisingly, the authors find that parthenogenetically produced females are likely produced by two distinct genetic mechanisms. The first results in clonality (maintenance of the maternal genotype), whereas the second one results in a loss of heterozygosity towards the telomeres, likely due to crossovers occurring between the centromeres and the telomeres. Moreover, bacterial infections appear to affect the propensity of parthenogenesis but are unlikely the primary cause. Together, the finding suggests that parthenogenesis is a variable trait in the species, both in terms of frequency and mechanisms. It is not entirely clear to what degree this variation is heritable, but if it is, then these results constitute evidence for low-frequency existence of variable and heritable parthenogenesis phenotypes, that is, the raw material from which evolutionary transitions to more regular forms of parthenogenesis may occur.

References Archetti M (2010) Complementation, Genetic Conflict, and the Evolution of Sex and Recombination. Journal of Heredity, 101, S21–S33. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esq009 Capdevielle Dulac C, Benoist R, Paquet S, Calatayud P-A, Obonyo J, Kaiser L, Mougel F (2022) Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process? bioRxiv, 2021.12.13.472356, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.13.472356 Engelstädter J (2008) Constraints on the evolution of asexual reproduction. BioEssays, 30, 1138–1150. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.20833 Ferree PM, Aldrich JC, Jing XA, Norwood CT, Van Schaick MR, Cheema MS, Ausió J, Gowen BE (2019) Spermatogenesis in haploid males of the jewel wasp Nasonia vitripennis. Scientific Reports, 9, 12194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48332-9 van der Kooi CJ, Matthey-Doret C, Schwander T (2017) Evolution and comparative ecology of parthenogenesis in haplodiploid arthropods. Evolution Letters, 1, 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.30 Lenormand T, Engelstädter J, Johnston SE, Wijnker E, Haag CR (2016) Evolutionary mysteries in meiosis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371, 20160001. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0001 Little CJ, Chapuis M-P, Blondin L, Chapuis E, Jourdan-Pineau H (2017) Exploring the relationship between tychoparthenogenesis and inbreeding depression in the Desert Locust, Schistocerca gregaria. Ecology and Evolution, 7, 6003–6011. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3103 Neiman M, Sharbel TF, Schwander T (2014) Genetic causes of transitions from sexual reproduction to asexuality in plants and animals. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 27, 1346–1359. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12357 Ryder OA, Thomas S, Judson JM, Romanov MN, Dandekar S, Papp JC, Sidak-Loftis LC, Walker K, Stalis IH, Mace M, Steiner CC, Chemnick LG (2021) Facultative Parthenogenesis in California Condors. Journal of Heredity, 112, 569–574. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esab052 Schwander T, Vuilleumier S, Dubman J, Crespi BJ (2010) Positive feedback in the transition from sexual reproduction to parthenogenesis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277, 1435–1442. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.2113 Stalker HD (1954) Parthenogenesis in Drosophila. Genetics, 39, 4–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/39.1.4 Vorburger C (2014) Thelytoky and Sex Determination in the Hymenoptera: Mutual Constraints. Sexual Development, 8, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356508 Watts PC, Buley KR, Sanderson S, Boardman W, Ciofi C, Gibson R (2006) Parthenogenesis in Komodo dragons. Nature, 444, 1021–1022. https://doi.org/10.1038/4441021a | Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process? | Claire Capdevielle Dulac, Romain Benoist, Sarah Paquet, Paul-André Calatayud, Julius Obonyo, Laure Kaiser, Florence Mougel | <p style="text-align: justify;">Hymenopterans are haplodiploids and unlike most other Arthropods they do not possess sexual chromosomes. Sex determination typically happens via the ploidy of individuals: haploids become males and diploids become f... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Reproduction and Sex | Christoph Haag | 2021-12-16 15:25:16 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer